Abstract

BACKGROUND

Bathing is a fundamental nursing care activity performed for or with the self-assistance of critically ill patients. Few studies address caregiver and/or patient-family perspectives about bathing activity during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation.

OBJECTIVE

To describe practices and beliefs about bathing patients during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV).

METHODS

Secondary analysis of qualitative data (observational field notes, interviews, and clinical record review) from a larger ethnographic study involving 30 patients weaning from PMV and the clinicians who cared for them using basic qualitative description.

RESULTS

Bathing, hygiene, and personal care were highly valued and equated with “good” nursing care by families and nurses. Nurses and respiratory therapists reported “working around” bath time and promoted conducting weaning trials before or after bathing. Patients were nevertheless bathed during weaning trials despite clinicians expressed concerns for energy conservation. Clinicians’ recognized individual patient response to bathing during PMV weaning trials.

CONCLUSION

Bathing is a central care activity for PMV patients and a component of daily work processes in the ICU. Bathing requires assessment of patient condition and activity tolerance and nurse-respiratory therapist negotiation and accommodation with respect to the initiation and/or continuation of PMV weaning trials during bathing. Further study is needed to validate the impact (or lack of impact) of various timing strategies for bathing PMV patients.

Bathing is both a nursing ritual and a fundamental therapeutic nursing intervention. The ritualistic nature of bathing has been described as sacred,1 occupying an essential place in nursing’s repertoire and identity.2 Prior research on the short-term hemodynamic effects of bed baths and associated turning-repositioning activities during the acute phase of critical illness3–11 raise some clinical concern about the potential for bathing activity to temporarily increase the “work of breathing” and oxygen consumption, particularly during periods of weaning from mechanical ventilation. Little is known, however, about the actual effects of initiating bathing activities during the ventilator weaning trials or what guides clinicians’ decisions about bathing patients during weaning trials. Critical care clinicians’ practices and beliefs about the optimal timing and importance of bathing are of particular interest as they have the potential to facilitate or hinder weaning progress.12 Thus, we asked the following research question, “What are the bathing practices and beliefs about bathing patients during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation (PMV) in the ICU?”

Background

This clinical research question arose inductively from our observations and discussions with nurses and respiratory therapists during an ethnographic study of weaning patients from prolonged mechanical ventilation (NINR grant # R01-NR07973). It became evident to the researchers that bathing was one of the therapeutic nursing interventions central to planning daily weaning trials. When nurses, patients and family members spoke to us about patient care during weaning and their experience of weaning, they spoke of bathing and hygiene care. We explored the literature and found no studies of bathing during weaning from mechanical ventilation, and very little to actually guide clinical decision making about when and how to bathe patients who are in the recovery phase of critical illness.

Bed baths and turning have been shown to result in a transient decrease in mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) and variable effects on blood pressure in critically ill patients.3, 4, 8–10 However, studies of the physiological effects of activity in critically ill patients indicate a relatively low level of energy expenditure during a bed bath.13, 14 Using a sample of healthy volunteers, Verderber and Gallagher15 demonstrated that anterior bath and passive range of motion exercises had minimal effects on oxygen consumption. However, turning and back care produced a significant increase in oxygen consumption.

Decreases in SvO2 of 9 to 13% can be expected after bathing and/or turning with less of a decrease during the bathing phase.3, 11 Physiological recovery from bathing and turning is usually relatively rapid, ranging from 3 to 16 minutes.3, 4, 7–9 Atkins and colleagues3 demonstrated no benefit from the addition of a 10-minute rest period between bathing and turning phases of a bed bath in hemodynamically stable coronary artery bypass graft patients. The greatest decrease in SvO2 was associated with bed baths in mechanically ventilated patients on high inspired oxygen concentrations (FiO2) and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) settings.8

In summary, the evidence from physiological research suggests that most critically ill patients recover fairly quickly from the physiological effects of bathing and that the energy expenditure during bathing is not excessive. However, the literature also reports clinician concerns about energy-oxygenation demands during weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Qualitative studies report that both patients and nurses endorse the importance of reducing or balancing energy demands during weaning from mechanical ventilation.12, 16–20. Nurses interviewed in Jenny and Logan’s classic study 12 reported using knowledge of the patient to tailor their interventions to manage each patient’s energy resources, including reducing energy demands during weaning. Ways to reduce energy demands included “initiating a slower pace of weaning, coordinating the patients’ activities and promoting a calm affect”12. Lomborg and colleagues17–19 reported that nurses and hospitalized patients with severe pulmonary disease employed strategies to minimize breathlessness and preserve personal integrity, such as pacing or curtailing body care, during bathing and body care activities. Although balancing work and rest was a major concept identified in Taylor’s comparative study20 examining the decision making processes of medical and nursing staff in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation, the nurse participants did not specifically discuss decisions about bathing activities during weaning trials. It is unclear how nurses and respiratory therapists, consider bathing activities as they plan care and balance energy demands for patients who are weaning from PMV.

Most prior studies of bathing in the ICU were conducted with cardiac, post-revascularization, or surgical ICU patients 3, 4, 6, 7, 9–11, 14 who typically recover quickly from critical illness. We found no published studies addressing the use or effects of bed baths on weaning from PMV. Updated Medline and CINAHL searches for published articles from the last ten years (1997–2008) using keywords ‘bathing/bath’ and ‘intensive care/critical care’ for adults revealed only studies addressing infection control or bathing as a self-care activity outcome measure. There are no empirical studies investigating when or how to bathe ICU patients who are weaning from PMV. Consequently, clinicians have little evidence on which to base decisions about how to best integrate activities such as bathing into the plan of care during weaning from PMV. In this study, we sought to describe practices and beliefs about bathing patients during weaning from PMV in the ICU.

Methods

Design

This qualitative secondary analysis was extracted from a larger parent study that used micro-level ethnography21. Micro-level ethnography is a “close-up view, as if under a microscope, of a small social unit or an identifiable activity within the social unit”21. Data collection for this study (i.e., observations and interviews with patients, family members, and critical care clinicians) focused on activities related to bathing and weaning trials. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Signed informed consent was obtained from patients or their proxies for all patient participation, and from families and clinicians for participation in interviews.

Setting

The study was conducted in the medical intensive care unit (MICU) of a tertiary care medical center from November, 2001 to July, 2003. The MICU was a 20 bed unit with an adjacent eight bed step-down unit. Most PMV patients were transferred to the step-down ICU for weaning trials. At the time of the study, the MICU admitted approximately 103 patients annually who required mechanical ventilation for > 48 hours and multiple weaning trials in the step-down unit22. Patient care was managed by critical care/pulmonary fellows or an acute care nurse practitioner under the direction of an attending physician. Nurses and respiratory therapists rotated between the more acute MICU and the step-down unit.

There were no specific policies or protocols guiding weaning or bathing. Type of bed bath (bath-in-a-bag or basin with water) was determined at the nurse’s discretion. Choices were influenced by availability of supplies (i.e., bath-in-a-bag) and nurse’s preference. A broad weaning strategy was used in this unit20. Patients were weaned by gradually reducing continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) to <12cm H20 and/or by spontaneous breathing trials using a tracheostomy mask or T-piece in a “patient-limited” weaning approach. Respiratory therapists initiated weaning trials at the direction of the medical team (physicians or nurse practitioner). Weaning trials were stopped or “limited” based on clinical assessment of individual patient response, primarily vital signs and respiratory parameters.

Sample

Thirty adult patients, who were weaning from PMV, were purposively selected for variation in age, gender, race, neurocognitive status (Glasgow Coma Score), severity of illness (APACHE III), and primary diagnosis. These criteria were derived from the literature on weaning from PMV, a companion clinical trial, 22 and our ongoing analysis. PMV was defined as 4 or more days of mechanical ventilation and 2 unsuccessful weaning attempts. Patients were followed throughout the period of weaning from mechanical ventilation in the ICU.

Clinicians received written and verbal information about the study; 31 clinicians (11 physicians, 10 nurses, 7 respiratory therapists, 3 others) were selected to participate in formal interviews. Selection was based on the clinician’s involvement in the care of study patients. Data used in this secondary analysis were primarily from observations and interviews with nurses and respiratory therapists. Data from interviews with family members (n=31), ranging in age from 27–74 years, and patients were used primarily to complement, confirm, or refute clinician perspectives. Table 2 lists characteristics of clinician and family member interview participants.

Table 2.

Demographics of Clinicians and Family Member Participants

| Clinicians | n | Sex | Race | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| male | female | W | AA | L | Asian | ||

| Physicians* | 11 | 10 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Respiratory Therapists | 7 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nurses# | 10 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Social Worker | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Physical Therapist | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nutritionist | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subtotal | 31 | 14 | 17 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Family Members (n=31) | n | Sex | Race | ||||

| male | female | W | AA | ||||

| Spouse | 15 | 8 | 7 | 15 | 0 | ||

| Adult Child** | 8 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 1 | ||

| Parent | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0 | ||

| Sibling | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Subtotal | 31 | 12 | 19 | 28 | 3 | ||

includes attending physicians, critical care medicine & pulmonary medicine fellows.

includes acute care nurse practitioner and nurse case manager.

includes son-in-law.

W= white/Caucasian; AA= African American; L= Latino/Hispanic; Asian = Asian-Pacific Islander

Data Collection

Observations

Qualitative data collection techniques included field observations of weaning events conducted by one of two researchers (JT, MBH) in the clinical setting 4–5 days/week including evenings and weekends.23–26 Observations followed a semi-structured guide, adapted from previous work,27, 28 that included description of patient activities and care activities during weaning. Observations were recorded by handwritten and dictated field notes. Observations were primarily focused on the weaning trials and weaning process. To protect patient privacy, bathing activities which were usually not directly observed; however clinicians and patients were debriefed about these activities to the extent that they related to weaning from PMV.

Interviews

Informal interviews were conducted during fieldwork. Semi-structured, audiotaped interviews were conducted with selected patients, clinicians, and family members. The patient interview guide included questions about their experience and feelings during weaning, actions by others that they perceived as helpful and/or unhelpful during weaning from PMV. Clinicians and family members were asked similar questions about actions that they perceived to be helpful or unhelpful to patients during weaning. Discussion about bathing occurred when we asked clinicians to describe typical care procedures and their daily routine in weaning patients from PMV. As “work,” rest, and bathing became important and interrelated concepts in the qualitative analysis, we asked clinicians more probing questions about the effects and timing of bathing during weaning trials. Specifically, we asked, “Tell me about work and rest. Are patients able to do other things while they wean - like bathing, sitting up in the chair?”

Clinical record review

To describe the sample, demographic data were collected from the clinical record: age, diagnosis, severity of illness at the onset of weaning (APACHE III), length of stay, and discharge disposition

Data Analysis

Field notes and interviews were transcribed verbatim and reviewed for accuracy. Textual files were transferred into ATLAS.TI version 5.0 (Scientific Software Development, 2004) for data organization and management. Files were labeled with unique (patient) case identifiers as well as data type (e.g., interview, observation) and source (e.g., nurse, respiratory therapist, patient, family member). Micro-level ethnographic methods commonly include grounded theory analytic techniques.21 Open and axial coding procedures using techniques of constant comparison analysis within and across cases were applied to transcripts of field notes, interviews, and family meetings.29 Qualitative data analysis began with the first observation and continued throughout the study. Data were coded, or labeled, by comparing new data with previous data and by questioning within and across cases.29 The coding schema was created by team consensus on coding definitions and grouping codes into categories. Data were coded by comparing new data with previous data and by questioning within and across cases.29 The coding schema was created by team consensus on coding definitions and grouping codes into categories beginning with line-by-line review of the first series of observations, interviews and cases. Dual coding (MBH, VS) with negotiated consensus was conducted on approximately 40% of the data was used to maintain rigor. Dual coding involved line by line review by a second coder of the primary coder’s analysis for consistent application or expansion of coding definitions.30 Hygiene, work and rest were codes frequently applied to the transcribed text. Hygiene included any reference to personal care, cleaning, bathing, and dressing changes. In particular, bathing recurred in the observational and clinician interview data as a factor influencing decisions to start, delay, or stop a weaning trial. Resting was a code applied to descriptions of sleep, fatigue, and/or the need to rest or conserve energy to promote weaning. Work was a code applied to descriptions of energy expenditure, effort, or exertion by the patient during weaning as well as opinions from participants about weaning as work or exercise, requiring physical strength or stamina. For this secondary analysis we reviewed the textual data coded as hygiene, work and rest for patterns, commonalities and differences to create a full description of practices and beliefs about bathing during ventilator weaning.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Thirty (n=30) critically ill patients receiving PMV, 25 to 87 years of age (Mean= 59.5, SD=17.6 years) Most (87%) were Caucasian and half were women. Patient characteristics are displayed on Table 1. Two outliers with extremely long ICU courses were excluded from the “trimmed” mean calculations for lengths of stay and days on mechanical ventilation. Clinician and family member characteristics are described in Table 2. Perspectives about Bathing During Weaning.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Mean ± SD | Trimmed Mean ± SD | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.5 ± 17.64 | 59.5 | 25–87 | |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 76.5 ± 163.0 | 38.2 ± 24.1a | 32.0 | 7–876 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 47.5 ± 63.0 | 34.0 ± 21.8a | 30.0 | 7–350 |

| Duration of MV (days) | 67.8 ± 164.6 | 28.9 ± 21.2a | 28.0 | 5–875 |

| n (%) | ||||

| Female Gender: | 16 (53) | |||

| Ethnicity: | ||||

| African-American | 4 (13) | |||

| Caucasian | 26 (87) | |||

| Primary Medical Dx: | ||||

| Cardio-pulmonary | 17 (57) | |||

| Surgical complication | 5 (17) | |||

| Cancer | 3 (10) | |||

| Neuromuscular | 5 (17) | |||

| Neurocognitive Status (Glasgow Coma Score):* | ||||

| Severe (≤8) | 4 (13) | |||

| Moderate (9–12) | 9 (30) | |||

| High (13–15) | 17 (57) | |||

| Disposition | ||||

| Died in Hospital | 5 (17) | |||

| Home | 8 (27) | |||

| LTC/LTAC/rehab | 14 (47) | |||

| Other hospital | 3 (10) | |||

Glasgow Coma Score measured on first day in step-down ICU

Two outliers were excluded from the computation of the trimmed mean and standard deviation.

LOS = Length of Stay, LTC = long term care, LTAC= long term acute care, rehab = rehabilitation hospital

Adapted with permission from Elsevier, Mosby, Inc. Heart and Lung, 2007; 36 (1): 49.

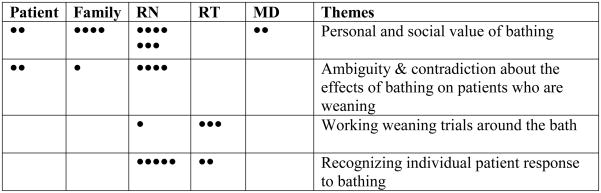

The main themes that describe practices and beliefs about bathing during ventilator weaning in the ICU are: (1) the personal and social value of bathing; (2) ambiguity and contradiction about when to bathe patients who are undergoing weaning trials; (3) working weaning trials around the bath; and (4) recognizing individual patient response to bathing. A stem leaf plot (Figure 1) illustrates the sources and strength of the themes in individual textual documents. Bathing practices with patients who were weaning from PMV were made within the context of strong personal and social values and beliefs about bathing and hygiene. Clinicians’ opinions of conducting baths during weaning trials were ambiguous and characterized by contradiction. Respiratory therapists often worked around the patient’s bath which was scheduled and implemented by the nurse. Both respiratory therapists and nurses recognized individual variation in patients’ responses and tolerance to bathing during PMV weaning trials.

Figure 1. Strength and Source of Themes.

Note: Only one • is allocated per source regardless of number of times the theme may appear in source documents.

Personal and Social Value of Bathing

Nurse and family member interviews clearly reflected the social significance and their beliefs about the importance of bodily cleanliness and appearance. Hygiene care was associated with attentiveness, caring and “good” nursing care, and was viewed as central to the nursing role in caring for chronically critically ill patients. Nurses proudly described storing special cologne, lotions, a portable hair dryer, and hair care products that they brought in to the hospital for use with their individual patients.

RN: I get my patients, I bathe them…. I’m the one that has to keep the patient clean, the medications appropriate…that’s my job.

RN: A cleaner patient looks better …

Physician: They just look better. They’re clean, they look better. …And then I think that effects whether people think they’re going to be able to wean or not if they look better in general. …. If you have a patient who’s in the chair and he’s all clean and on the ventilator. He looks a lot better than a patient who is dirty and lying flat in bed.

Wife: But a nurse who’s more attentive is going to keep her patient clean. A nurse who is more aware of the comfort of the patient, not only (is she) catering to the patient’s loved ones who want to see them clean but somehow I do think, I do equate that with attentiveness.

Sister: I said (to the nurse), “You’re really right at the top of my list. You really are, you shampoo his hair everyday, you shave him, you give massages, you put cologne on him and I could see that you’re really excited about making him look good. And that makes me feel good.”

Interviewer: What did (the nurse) do that you think was really helpful?

Patient: She helped clean me.

Nurses identified hygiene and grooming as a non-pharmacologic intervention to facilitate patient recovery. In fact, hygiene care was often the nurses’ first response to our general clinician interview question, “Tell me what you do for patients who are weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation?”

RN: Oh you know you kind of straighten her up and wash her face if it’s not time for their bath yet. You know you do something like that. You pamper her a little bit you know, show her that you’re here to care a little bit.

Fieldnote: The nurse commented that she has the patient shaved and up in the chair this morning, she applied a cologne lotion that she carries in her pocket and was proud of that.

She was not alone, others revealed private supplies of personal care products that they used with patients.

A nurse participant relayed an interaction that she had with a patient’s husband who was described as “difficult,” dissatisfied, and overly protective. The husband asked about a bath for his wife, “Can you believe that she hasn’t had a bath since Saturday?” When the nurse expressed disbelief, the patient’s husband immediately took offense saying, “Are you calling me a liar?” The nurse astutely and calmly responded, “No. I’m going to give her a bath and wash her hair.” As she provided immediate caring attention to the patient, she began to win the husband’s trust and soothe his dissatisfaction. By this simple, but powerful act, the nurse began a primary caring relationship with husband and patient that lasted several months until the patient’s death.

Ambiguity and Contradiction

Clinicians’ interviews revealed ambiguity and contradiction about the optimal timing and potentially deleterious effects of performing bed baths during weaning trials. Considerations about the timing of bed baths were part of clinicians’ daily planning and critical thinking about the patient’s weaning process. Clinicians anticipated that bathing would precipitate physiological (vital sign) changes and agitation in patients prone to agitation.

RT: And, really, [the blood pressure] hasn’t really gone up from her baseline of 170 systolic. She even had a bath and everything and I was suspecting that she would get agitated or her blood pressure would go up with that, but it really stayed okay.

In the following interview, a critical care nurse explains deliberately planning for patients’ energy conservation during weaning trials. This interview also contains somewhat paradoxical descriptions of grouping energy consumptive activities together before the weaning trial and/or “saving up energy” by delaying activities until after the weaning trial is completed.

RN: I try to do all the things that will make them more tired or have any influence on (the wean) whatsoever before the wean…Bathing, turning, getting out of bed to the chair, physical therapy, or occupational therapy, with all those exercises. Any extra little thing, we always try to do it before they go on the wean, so it’s not part of why they didn’t tolerate the wean.

[Later in interview] Planning the day so that interventions are done maybe after the wean so they’re not so tired for the wean or maybe just doing one intervention before the wean, keeping all their strength for the wean and then tackling the bath and the PT and the OT…saving up their energy for the wean.

Although the following observation did not occur during a weaning trial, it is a further example of contradiction about activity tolerance and planning bathing activities. The patient was experiencing atrial fibrillation and mental status changes while sitting in a chair.

RN1: (The patient) looks even more confused now…I think he needs to go back in bed.

RN2: Okay. Well we’ll put him back to bed.

RN1: Yeah, we’ll put him back to bed and then we’ll give him a bath.

Although family members associated patient cleanliness with good nursing care, families and patients also reported concerns about negative physiological effects of bathing during weaning.

Research Field Note: The husband and daughter spent ten minutes describing their impressions to me that the physical care, bathing in particular, was affecting their mother’s progress. They felt that the proximity of the hygiene intervention to the weaning attempt caused the patient to become fatigued and not to be able to continue.

Patient: When they were washing me and stuff in here and if I wasn’t on the machine (ventilator), I’d die…(bathing) required strength. But I had to learn…They say “breathe deeply, cough.” But when I tried that I got out of breath. It was just too much labor for me. At that time, I was just that weak.

Patient: That (therapist name) from physical therapy was in here working me over. Then those two nurses came in here and gave me a bath. I’m exhausted.

Working around the Bath

Nurses were clearly in charge of the timing and conduct of bathing these patients. Respiratory therapists deferred to nurses’ choices about bathing activities as they planned and scheduled weaning trials.

RT: Maybe (the nurse) will have a reason that she doesn’t want me to start (the weaning trial) right away. Maybe she wants to given them an early morning bath, then there’s no use in me starting (the weaning trial), having her get the bath, and having the patient fail. So you have to kind of work around that too.

RN: They (RTs) almost always ask or if they come into the room and they want to start something (weaning trial)…I’ll sometimes say “oh I was just getting ready to bathe them, can you wait a half an hour?” And it’s absolutely always never a problem. They just come back.

Timing of the bath was, however, an occasional source of interdisciplinary conflict as bathing impacted work plans for respiratory therapists as well as therapeutic plans (e.g., weaning trials) for patients.

RT: You’ll come in here and you’ll no sooner want to start a patient (on a weaning trial) at 9:00AM and the nurse goes “Well, I was going to bathe him.” Well you know that they’re getting weaned in the morning and there’s a good chance that they’re not going to tolerate both …In my personal opinion, …bathing should not be part of the morning ritual, unless you can get it done (before they start the weaning trial). …even with (the patient) on assist control (non-weaning ventilator setting), you may tire them out to the point them may have no reserve to where the wean’s shot that morning.

Although weaning trials were sometimes delayed until the bath was finished, clinicians did not describe or specify an optimum recovery time after bathing before starting a weaning trial. In fact, we observed several instances of weaning trials beginning almost immediately following completion of the bath. The following comment from a respiratory therapist reveals that even when bathing occurred during a weaning trial, ventilator adjustments toward greater patient effort at weaning were delayed until the bathing activity was completed.

RT: She’s doing real well on (CPAP)5 and (Pressure Support)5. I’m going to put her on TM (trach mask) after (the nurse) is done with her bath.

Recognizing Individual Patient Response

Clinicians recognized patients’ responses to bathing as individual and variable. They associated patients’ responses to bathing with the patient’s condition and illness severity. There was recognition that activity tolerance during ventilator weaning was a sign of recovery and a necessary condition for full liberation from PMV.

RT: (It) depends on how critical they are. I’ve had people on weans and a bath has been fine and things have been fine.

RT: And a lot of times nurses and physical therapists, will ask me and it depends on the patient. It’s nice when they ask. They’ll say “Should I? We’re going to be working with (the patient). Do you want to do anything different? Do you want to take them off (the weaning trial)?” And sometimes I will and sometimes I won’t. I will let them even go through a bath sometimes on a wean, you know, thinking that they’re close to being off the ventilator. They’re going to have to deal with it. You know, at least I can monitor them at this point on the ventilator.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to use prolonged observation and interview to qualitatively describe the care patterns involved in weaning patients from long term mechanical ventilation. Taylor’s qualitative study20 interviewed clinicians (nurses and physicians only) about case scenarios to describe clinical decision making in the process of weaning patients from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Bathing was not mentioned by clinicians in that study as they described balancing work and rest in terms of clinical decisions to adjust oxygen concentration and ventilatory support to provide “rest” on the ventilator for patients who tire from the work of weaning. As researchers (and nurses), we initially overlooked bathing as a routine and uninteresting aspect of the care of patients who were weaning from PMV. Because bathing and hygiene care recurred frequently in our observations of weaning events and in our informal and formal interviews with study participants, we were led to more closely examine this relatively unexamined aspect of care for patients weaning from PMV.

Personal and Social Value of Bathing

This study confirms Wolf’s2 analysis of bathing as a highly valued activity central to the role of the nurse in the care of seriously ill patients. Bathing and personal hygiene care has been described as intimate and “dirty” work 1, 31, yet nurses in our study recognized and valued the importance of bathing in providing this attention and personal care. Families of patients receiving PMV equated bathing and attention to the patient’s hygiene and appearance with good nursing care. This strong social norm may reflect American cultural norms about cleanliness and grooming as well as expectations about the nurse’s role. Likewise, emphasis on cleanliness and hygiene in the care of the sick and prevention of infection is evident in the writings of Florence Nightengale 32 and basic instruction in nursing fundamentals 33. Clearly, nurses in our study received this message and valued this aspect of their work. Benner and colleagues described care of the (patient’s) body in the form of grooming and bathing as a source of comfort to both critically ill patients and their nurses.34.

Ambiguity and Contradiction

Despite the high value placed on bathing, our data also show that critical care clinicians hold conflicting and ambiguous opinions about the positive or negative effects of bathing patients during ventilator weaning trials with respect to tolerance or success of the weaning activity. From a positive viewpoint, clinicians saw benefits of hygiene and appearance as promoting well-being. From a negative viewpoint, consistent with Jenny and Logan’s12 interview findings, conservation of energy for weaning was a primary concern expressed by clinicians who saw bathing activity as potentially inhibiting tolerance of weaning trials for PMV patients. This concern was aligned with patient and family descriptions of effort, fatigue, and labor when bathing during weaning trials. Similarly, non-mechanically ventilated hospitalized patients with severe pulmonary disease reported breathlessness and fatigue during bathing and personal care activities19. Clinicians in our study expected, but did not always see, some negative physiological response during weaning. This finding is consistent with research to date on the physiological effects of bathing on critically ill patients wherein changes in heart rate, blood pressure, and SVO2 occur but are rarely sustained. 3, 4, 7, 9, 11, 35. Lomborg and colleagues19 also reported that bathing and personal body care did not always increase breathlessness for hospitalized patients with severe pulmonary disease. Bed baths were, in fact, preferred as less exhausting than bedside or shower washing by some of the participants in their study.

Working around the Bath

Although nurses and respiratory therapists focused on the fundamental nursing principle of energy conservation,36 there was no clear consensus among the team regarding how energy conservation would be best achieved during weaning trials as indicated by deference to the nurse’s activity schedule and occasional conflict about the timing of baths. Our data confirm that nurses are the gatekeepers and organizers of activities for patients who are weaning from PMV in intensive care and step-down intensive care units. Protocolized weaning directed by nurses or respiratory therapists has been shown to reduce weaning times. 37–39 Computer-driven protocolized weaning also showed reductions in weaning duration, duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU length of stay 40. There are no details in these research reports regarding whether or how nurses modified care or patient activities during weaning trials. This study provides new descriptive evidence detailing collaboration between nurses and respiratory therapists about bathing activities as a component of weaning trial interdisciplinary work patterns, communication, and care.

Recognizing Individual Patient Variation

Clinicians in our study recognized individual variation among PMV patients in response to bathing activity and expressed greatest caution for patients who were most seriously ill. Similarly, the physiological research on bathing showed the greatest and most sustained negative effect of bathing among critically ill mechanically ventilated patients who were receiving high levels of pressure support and oxygen concentrations indicating a more serious level of respiratory compromise.35 Overly prescriptive protocols or unit bathing routines would not be consistent this type of individualized or personalized care which depends on knowing the patient and understanding his/her activity tolerance.12 Using a grounded theory approach, Lomborg and Kirkevold17 identified “achieving therapeutic clarity” between hospitalized patients with severe pulmonary disease and nurses as essential to the process of assisted bathing and personal body care. Patients in their study were not mechanically ventilated, however, negotiating roles, pace, and scope of assistance in bathing and personal body care were key components for a positive patient experience. For patients weaning from PMV, a rehabilitative care approach would favor progressive activity including bathing and personal care activities during weaning trials.41, 42

Limitations

The major limitation of this study is that bathing practices and responses to bathing were not the primary focus of observations and interviews which were centered on weaning events and the process of weaning patients from PMV. We did not directly observe bed baths nor did we quantify or qualify the type of baths provided to patients during weaning trials. A critical care nurse’s choice to bathe patients during a weaning trial may have been influenced by competing demands and care planning for other patients, such as anticipating a new admission, the need to accompany a patient to a test, or the provision of emergency care. The single site, an urban tertiary care center, may also limit transferability of findings.

Conclusion

Bathing is a central care activity for patients weaning from PMV. Nurses are the gatekeepers and organizers of activities for patients who are weaning from PMV in intensive care and step-down intensive care units. Negotiation and collaboration with respiratory therapists about possible weaning trial adjustments in relation to bathing activities is a component of daily nursing care and interdisciplinary communication processes during weaning. “Therapeutic clarity”17 and negotiations about bathing may involve triadic interaction between patient, nurse, and respiratory therapist. Nurses and respiratory therapists need evidence regarding the impact of bathing patients during a weaning trial on duration of the weaning trial. Similarly, the effects of other patterns of bathing, such as, prior to the weaning trial or late at night, should be explored.

Acknowledgments

Work performed at the University of Pittsburgh and supported by the National Institute for Nursing Research, NIH, U.S. Public Health Service (Grant No. R01 NR007973; M. Happ, PI)

Thanks to Colleen Casey, PhD, RN, CRNP for critical review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wolf ZR. Nurses’ work, the sacred and the profane. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf ZR. The bath: A nursing ritual. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 1993;11(2):135–48. doi: 10.1177/089801019301100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atkins PJ, Hapshe E, Riegel B. Effects of a bedbath on mixed venous oxygen saturation and heart rate in coronary artery bypass graft patients. American Journal of Critical Care. 1994;3(2):107–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Copel LC, Stolarik A. Impact of nursing care activities on Svo2 levels of postoperative cardiac surgery patients. Cardiovascular Nursing. 1991;27(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doering LV. The effect of positioning on hemodynamics and gas exchange in the critically ill: A review. American Journal of Critical Care. 1993;2(3):208–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnston BL, Watt EW, Fletcher GF. Oxygen consumption and hemodynamic and electrocardiographic responses to bathing in recent post-myocardial infarction patients. Heart & Lung. 1981;10(4):666–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis P, Nichols E, Mackey G, Fadol A, Sloane L, Villagomez E, Liehr P. The effect of turning and backrub on mixed venous oxygen saturation in critically ill patients. American Journal of Critical Care. 1997;6(2):132–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noll ML, Duncan CA, Fountain RL, Weaver L, Osmanski VP, Halfman S. The effect of activities on mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) in critically ill patients. Heart & Lung. 1991;20(3):301. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shively M. Effect of position change on mixed venous oxygen saturation in coronary artery bypass surgery patients. Heart & Lung. 1988;17(1):51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tidwell SL, Ryan WJ, Osguthorpe SG, Paull DL, Smith TL. Effects of position changes on mixed venous oxygen saturation in patients after coronary revascularization. Heart & Lung. 1990;19(5 Pt 2):574–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winslow EH, Clark AP, White KM, Tyler DO. Effects of a lateral turn on mixed venous oxygen saturation and heart rate in critically ill adults. Heart & Lung. 1990;19(5 Pt 2):557–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jenny J, Logan J. Promoting ventilator independence: A grounded theory perspective. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing. 1994;13(1):29–37. doi: 10.1097/00003465-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swinamer DL, Phang PT, Jones RL, Grace M, King EG. Twenty-four hour energy expenditure in critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine. 1987;15(7):637–43. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198707000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman C, Kemper M, Damask MC, Askanazi J, Hyman AI, Kinney JM. Effect of routine intensive care interactions on metabolic rate. Chest. 1984;86(6):815–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.86.6.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verderber A, Gallagher KJ. Effects of bathing, passive range-of-motion exercises, and turning on oxygen consumption in healthy men and women. American Journal of Critical Care. 1994;3(5):374–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Logan J, Jenny J. Qualitative analysis of patients’ work during mechanical ventilation and weaning. Heart & Lung. 1997;26(2):140–7. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lomborg K, Kirkevold M, Lomborg K, Kirkevold M. Achieving therapeutic clarity in assisted personal body care: professional challenges in interactions with severely ill COPD patients. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(16):2155–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomborg K, Kirkevold M, Lomborg K, Kirkevold M. Curtailing: handling the complexity of body care in people hospitalized with severe COPD. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2005;19(2):148–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lomborg K, Bjorn A, Dahl R, Kirkevold M, Lomborg K, Bjorn A, Dahl R, Kirkevold M. Body care experienced by people hospitalized with severe respiratory disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;50(3):262–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor F. A comparative study examining the decision-making process of medical and nursing staff in weaning patients from mechanical ventilation. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing. 2006;22(5):253–63. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fetterman D. Ethnography. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman LA, Tasota FJ, Zullo TG, Scharfenberg C, Donahoe MP. Outcomes of care managed by an acute care nurse practitioner/attending physician team in a subacute medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2005;14(2):121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Happ MB, Dabbs AD, Tate J, Hricik A, Erlen J. Exemplars of mixed methods data combination and analysis. Nursing Research. 2006;55(2 Suppl):S43–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200603001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Happ MB, Swigart V, Tate J, Crighton MH. Event analysis techniques. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27(3):239–48. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200407000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Happ MB, Swigart V, Tate J, Hoffman L, Arnold RM. Patient involvement in health related decision making during prolonged critical illness. Research in Nursing and Health. 2007;30(4):361–372. doi: 10.1002/nur.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Happ MB, Swigart VA, Tate JA, Arnold RM, Sereika SM, Hoffman LA. Family presence and surveillance during weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Heart & Lung. 2007;36(1):47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Happ MB, Roesch TK, Garrett K. Electronic voice-output communication aids for temporarily nonspeaking patients in a medical intensive care unit: A feasibility study. Heart & Lung. 2004;33(2):92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Happ MB, Roesch TK, Kagan SH. Patient communication following head and neck cancer surgery: A pilot study using electronic speech-generating devices. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32(6):1179–87. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.1179-1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strauss AL, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An expanded sourcebook. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jervis LL. The pollution of incontinence and the dirty work of caregiving in a U.S. nursing home. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2001;15(1):84–99. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nightingale F. Notes on nursing: What is, and what it is not. London: Harrison and Sons; 1859. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman GB. Delmar’s fundamentals and advanced nursing skills. 2. Clifton Park, NY: Delmar Learning Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benner P, Hooper-Kyriakidis P, Stannard D. Clinical Wisdom and Interventions in Critical Care: A Thinking-In-action Approach. 1. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders & Company; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noll ML, Duncan CA, Fountain RL, Weaver L, Osmanski VP, Halfman S. The effect of activities on mixed venous oxygen saturation (SvO2) in critically ill patients. Heart & Lung. 1991;20(3):301. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine ME. The four conservation principles of nursing. Nursing Forum. 1967;6(1):45–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6198.1967.tb01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ely EW, Bennett PA, Bowton DL, Murphy SM, Florance AM, Haponik EF. Large scale implementation of a respiratory therapist-driven protocol for ventilator weaning. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 1999;159(2):439–46. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9805120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kollef MH, Shapiro SD, Silver P, St John RE, Prentice D, Sauer S, Ahrens TS, Shannon W, Baker-Clinkscale D. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol-directed versus physician-directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Critical Care Medicine. 1997;25(4):567–74. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tonnelier JM, Prat G, Le Gal G, Gut-Gobert C, Renault A, Boles JM, L’Her E. Impact of a nurses’ protocol-directed weaning procedure on outcomes in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation for longer than 48 hours: a prospective cohort study with a matched historical control group. Critical Care (London, England) 2005;9(2):R83–9. doi: 10.1186/cc3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lellouche F, Mancebo J, Jolliet P, Roeseler J, Schortgen F, Dojat M, Cabello B, Bouadma L, Rodriguez P, Maggiore S, Reynaert M, Mersmann S, Brochard L. A multicenter randomized trial of computer-driven protocolized weaning from mechanical ventilation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;174(8):894–900. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1780OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomsen GE, Snow GL, Rodriguez L, Hopkins RO. Patients with respiratory failure increase ambulation after transfer to an intensive care unit where early activity is a priority. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(4):1119–24. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318168f986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, Taylor K, Harry B, Passmore L, Ross A, Anderson L, Baker S, Sanchez M, Penley L, Howard A, Dixon L, Leach S, Small R, Hite RD, Haponik E. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Critical Care Medicine. 2008;36(8):2238–43. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]