Summary

GPR30 is a novel, membrane-bound, G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (Filardo et al., 2002; Prossnitz et al., 2008). We hypothesize that GPR30 may mediate effects of estradiol (E2) on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and cognitive performance. Recently we showed that G-1, a selective GPR30 agonist, enhances the rate of acquisition on a delayed matching-to-position (DMP) T-maze task (Hammond et al., 2009). In the present study, we examined the distribution of GPR30 in the rat forebrain, and the effects of G-1 on potassium stimulated acetylcholine release in the hippocampus. GPR30-like immunoreactivity was detected in many regions of the forebrain including the hippocampus, frontal cortex, medial septum/diagonal band of Broca, nucleus basalis magnocellularis, and striatum. GPR30 mRNA also was detected, with higher levels in the hippocampus and cortex than in the septum and striatum. Co-localization studies revealed that the majority (63%–99%) of cholinergic neurons in the forebrain expressed GPR30-like immunoreactivity. A far lower percentage (0.4%–35%) of GABAergic (parvalbumin-containing) cells also contained GPR30. Sustained administration of either G-1 or E2 (5 µg/day) to ovariectomized rats produced a nearly three-fold increase in potassium-stimulated acetylcholine release in the hippocampus relative to vehicle-treated controls. These data demonstrate that GPR30 is expressed by cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain, and suggest that activation of GPR30 enhances cholinergic function in the hippocampus similar to E2. This may account for the effects of G-1 on DMP acquisition previously reported.

Keywords: Estradiol, G-1, Acetylcholine, Estrogen Receptor, Basal Forebrain Cholinergic System

Introduction

Studies show that 17-β-estradiol (E2) can significantly enhance basal forebrain cholinergic function and improve performance on a variety of cognitive tasks (reviewed in Gibbs, 2010). For example, E2 increases the expression of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) mRNA and protein in the medial septum and nucleus basalis magnocellularis (Gibbs, 1996; McMillan et al., 1996; Bohacek et al., 2008), and increases both ChAT activity (Luine, 1985; Gibbs, 2000) and high affinity choline uptake (O'Malley et al., 1987; Singh et al., 1995) in the hippocampus and cortex. E2 also increases potassium-stimulated acetylcholine (ACh) release in the hippocampus (Gibbs et al., 1997; Gabor et al., 2003), which correlates with effects on place learning (Marriott and Korol, 2003). Effects of E2 on acquisition of T-maze and radial arm maze tasks are blocked by either cholinergic denervation of the hippocampus (Gibbs, 2007), or by the inhibition of M2 muscarinic ACh receptors (Daniel and Dohanich, 2001). In rats, E2 attenuates amnestic effects induced by scopolamine (Fader et al., 1998; Fader et al., 1999; Gibbs, 1999). A similar effect was recently reported in humans (Dumas et al., 2006). Conversely, scopolamine at appropriate doses can block the memory-enhancing effects of E2 injected directly into the hippocampus (Packard, 1998). These findings demonstrate that E2 enhances basal forebrain cholinergic function, and that the cholinergic projections play a critical role in mediating effects of E2 on cognitive performance. The mechanisms, however, by which E2 affects the cholinergic neurons remain unclear.

We hypothesize that some of the effects of E2 on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons are mediated by GPR30. GPR30 is a member of the seven transmembrane G-protein coupled receptor family and mediates rapid signaling in response to E2 in several cell lines (Thomas et al., 2005; Prossnitz et al., 2008). Previous work from our laboratory showed that treating ovariectomized rats with G-1, a selective GPR30 agonist (Bologa et al., 2006), enhanced the rate of acquisition on a delayed matching-to-position (DMP) T-maze task similar to E2 (Hammond et al., 2009). Effects of E2 on DMP acquisition rely upon cholinergic projections to the hippocampus (Gibbs, 2007). The purpose of the present study was to evaluate GPR30 expression in the rat forebrain, to determine whether cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain express GPR30, and to test whether activation of GPR30 affects cholinergic function in the hippocampus as reflected by a change in ACh release.

Materials and Methods

Animals

A total of 22 young adult, ovariectomized, female Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Hilltop Laboratories. Ten rats were used for the immunohistochemical (n=5) and RT-PCR (n=5) experiments and 12 were used for in vivo microdialysis. Rats were individually housed on a 12-hour day/night cycle with food and water freely available. All procedures were carried out in accordance with PHS policies on the use of animals in research, and with the approval of the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Characterization of GPR30-like immunoreactivity (IR) in the forebrain

Rats were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine and perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde/0.05 M sodium acetate (pH 6.5) and then with 4% paraformaldehyde/0.05 M Tris (pH 9.0). Brains were removed, post-fixed for 2 hours in 4% paraformaldehyde/50 mM Sorenson’s phosphate buffer, and then stored in 20% sucrose/50 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). Adjacent series of 40 µm coronal sections were cut through the forebrain. Series were first incubated with a rabbit anti-GPR30 antiserum directed against the human C-terminus of GPR30 (0.1 µg/mL in 50 mM PBS containing 0.05% Triton X-100 and 5% normal horse serum). The GPR30 antibody was a gift from Edward Filardo (Brown University). This antibody was generated against the C-terminal peptide (KAVIPDSTEQSDVRFSSAV) corresponding to the terminal 18-amino acid residues from the deduced amino acid sequence of human GPR30 (Filardo et al., 2000). The C-terminal sequence in rat is nearly identical (KAVIPDSTEQSDVKFSSAV), differing by only one amino acid. Sections were placed in primary antibody solution for 3 days at 4°C. The sections were rinsed with 50 mM PBS and then incubated with biotinylated goat-anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, 1:200 dilution) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were rinsed again with PBS and incubated with an avidin-HRP complex (Vectastain Elite kit; Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were rinsed with PBS, placed in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB; 0.5 mg/mL), then reacted with 50 mM Tris containing DAB (0.5 mg/mL), H2O2 (0.01%) and NiCl2 (0.032%) for 10 min. Sections were then rinsed with PBS, mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Inc.), dehydrated, and coverslipped. Specificity was tested by blocking staining with purified C-terminal peptide (Novus Biologicals, Inc.) at a concentration of 10 µg/mL. Additional negative control sections were incubated with the secondary antibody but no primary antibody.

Co-localization of GPR30 and ChAT or Parv

For co-localization studies, tissues were prepared from 5 rats and sections were incubated with the GPR30 antibody as described above followed by a Cy3-labeled anti-rabbit IgG raised in donkey at a dilution (diluted 1:400; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Sections were then rinsed with PBS and incubated either with an antibody against ChAT (goat anti-ChAT, 1:1200 dilution; Chemicon International, Inc.) or with an antibody against parvalbumin (mouse anti-Parv, 1:16,000 dilution; Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.). Parvalbumin is a calcium binding protein that is expressed by GABAergic neurons in the basal forebrain (Freund, 1989; Kiss et al., 1990). These antibodies were detected using Alexa488-labeled secondary antibodies raised in donkey (diluted 1:400; Invitrogen). Negative controls underwent all processing steps, but omitted one or both primary antibodies. This controlled for non-specific staining and ruled out cross-reactivity between secondary antibodies. The order in which primary antibodies were added also was varied to control for order effects.

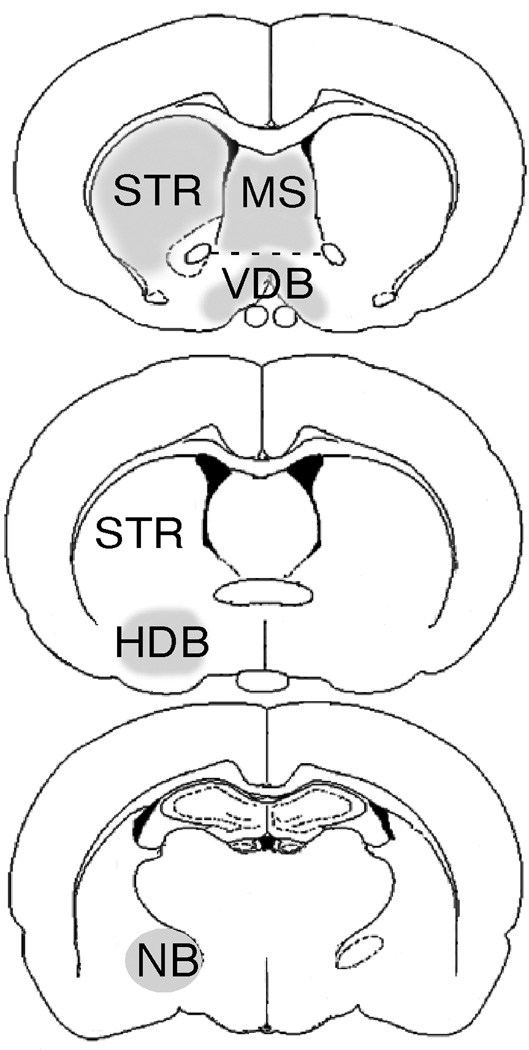

Labeled cells were imaged using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 confocal microscope. Regions containing populations of cholinergic neurons were analyzed. These included the medial septum, vertical (VDB) and horizontal (HDB) limbs of the diagonal band of Broca, nucleus basalis magnocellularis (NBM), and striatum (STR). Areas were defined by plate numbers in Paxinos and Watson (Paxinos et al., 1980). Sections through each region were selected from each rat and matched according to plate number (Table I). Within each section, the total number of ChAT- or Parv-immunoreactive cells in the region of interest and the percentage of these cells containing GPR30-IR were counted and calculated. Specific brain regions in which cells were counted are illustrated in Figure 1. Cells were included in the counting if they contained ChAT-or Parv-IR, had a defined cell body and a detectable nucleus. Defined ChAT or Parv-immunoreactive cells were first located and then examined for GPR30 labeling. Data are presented as average percentage of ChAT- and Parv-IR cells containing GPR30-IR per section.

Table I.

Table showing regions in which neurons were counted, plate numbers (from Paxinos & Watson (Paxinos et al., 1980)) that correspond to levels at which matched sections were selected and analyzed for double labeling, total ChAT or Parv positive neurons, and total number and percentage of double-labeled neurons.

| Region | Plate Number |

Number of Sections Analyzed Per Region Per Brain |

Total Number ChAT Positive Neurons |

Total Number ChAT and GPR30 Positive Neurons |

Percentage ChAT and GPR30 Double- Labeled Neurons |

Total Number Parv Positive Neurons |

Total Number Parv and GPR30 Positive Neurons |

Percentage Parv and GPR30 Double- Labeled Neurons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS | 14–18 | 5 | 3243 | 3093 | 95.38 | 1336 | 262 | 19.61 |

| VDB | 14–16 | 3 | 3698 | 2296 | 62.10 | 1060 | 374 | 35.28 |

| HDB | 17–20 | 4 | 3269 | 2216 | 67.79 | 1259 | 534 | 42.41 |

| NB | 23–24 14–18, |

2 8 |

1849 | 1504 | 81.34 | ---- | ---- | ----- |

| STR | 23–25 | 6669 | 6632 | 99.45 | 10962 | 40 | 0.36 |

Figure 1.

Drawings illustrating brain regions (areas in grey) in which numbers of ChAT- and Parv-IR cells containing GPR30-IR were counted. STR: striatum. MS: medial septum. VDB: vertical limb of diagonal band of broca. HDB: horizontal limb of diagonal band of broca. NB: nucleus basalis magnocellularis.

GPR30 mRNA detection

RT-PCR was used to verify the presence and to compare relative levels of GPR30 mRNA in regions of interest. Rats were anesthetized, decapitated, and brains were removed and dissected. Using a brain matrix, the anterior portion of the brain (+4.70 mm from Bregma) was discarded. The next 3 mm (4.70 - 1.70 mm from Bregma) containing frontal and prefrontal cortex were collected. Prefrontal cortex included regions Cg1, Cg2, and Fr2. Frontal cortex included regions Fr1 and Fr3. Next, a 3 mm slab (1.70 to −1.30 mm from Bregma) was collected containing the septum/VDB and striatum. The septum/VDB was dissected by collecting tissue between the lateral ventricles and anterior commissure. The hippocamapus was dissected from the remaining tissues. All tissues were frozen at −80°C. TRIzol (Invitrogen, Inc.) was added to each sample and total RNA was isolated as per manufacturer’s instructions. mRNA was then reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III kit (Invitrogen, Inc.). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR green and an ABI 7300 Sequence Detection System (ABI). All samples were run in duplicate, and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used to control for amount of mRNA added to the reaction. Negative controls for RT and PCR reactions included no template and no enzyme and also were performed in duplicate. The following primer sequences were used (listed in 5’–3’ direction):

GPR30 sense: AGGAGGCCTGCTTCTGCTTT

GPR30 antisense: ATAGCACAGGCCGATGATGG

GAPDH sense: TGCCACTCAGAAGACTGTGG

GAPDH antisense: GGATGCAGGGATGATGTTCT

These primers were created using Invitrogen’s Oligoperfect Designer. The coding sequence near the C-terminus was amplified, and these primers were generated to be 18–20 bases long, to have a primer Tm of 60–63°C, a GC content of 50%–55%, and to generate a product size of 80–130 bp. Data were analyzed using Sequence Detection System (SDS) software (ABI, Inc.), and results were obtained as Ct (threshold cycle) values. The average Ct for each set of duplicates was calculated. Relative expression of GPR30 was normalized to GAPDH by subtracting the average Ct for GAPDH from the average Ct for GPR30 (ΔCt) for each region per rat. The average ΔCt for each region was then calculated. Levels of GPR30 mRNA relative to the hippocampus were than calculated by subtracting the average ΔCt for each region from the average ΔCt for the hippocampus (ΔΔCt). Approximate GPR30 mRNA levels for each region were then calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Pfaffl, 2001). This entire process was performed three times, and ANOVA was used to determine significant differences in expression across brain regions.

Effects of G-1 on ACh release

In vivo microdialysis was used to compare the effects of G-1 with E2 on ACh release in the hippocampus. Ovariectomized rats were administered E2, G-1, or vehicle using an Alzet osmotic minipump (model 2006; Durect Corp., Inc.) implanted subcutaneously in the dorsal neck region. Drugs were administered continuously at a dose of 5 µg/day. This dose was selected based on our previous study which showed that 5 µg/day of either G-1 or E2 enhanced acquisition of a DMP T-maze task (Hammond et al., 2009). E2 was diluted in a vehicle of 13.9% DMSO + 20% hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD). G-1 was administered in a vehicle 33.7% DMSO+ 13.3% HPβCD. Half of the control group was treated with each of the vehicle solutions. At the time of pump implantation rats also received a microdialysis guide cannula (CMA 12 Elite Guides, CMA Microdialysis, Inc.) lowered into the right hippocampus (−3.4 mm bregma, 1.18 mm lateral, −3.4 mm ventral) and fixed to the skull using dental cement. Microdialysis was performed 7 days later.

Concentric, 3 mm microdialysis probes were used (CMA 12 Elite Probes, CMA Microdialysis, Inc.). Probes were perfused at a rate of 1 µl/min with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF; 144.3 mM NaCl, 4.0 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 1.0 mM MgCl2, 1.7 mM Na2HPO4, 0.5 mM NaH2PO4) containing 0.8 µM neostigmine bromide. On each day of microdialysis, probes were first dialyzed for 30 minutes against a solution of ACSF containing 0.1 pmol ACh/20 µL. This sample was used to calculate and correct for probe efficiency. The probe was then inserted through the cannula into the hippocampus. The rat was placed into a large plastic container for the duration of the experiment. Dialysate was collected continuously. Samples were collected and frozen every 30 min. After waiting 90 minutes for basal ACh release to stabilize, two additional samples were collected over one hour and were averaged to represent basal ACh release. Next probes were perfused with identical ACSF containing 60 mM potassium and samples were collected after 30 and 60 min. Probes were then perfused again with the ACSF containing 4.0 mM potassium and samples were collected every 30 minutes for an additional 60 minutes.

HPLC analysis

Dialysates were analyzed using HPLC, enzymatic conversion, and electrochemical detection as previously described (Rhodes et al., 1996). An ESA HPLC system was used. Flow rate was 0.35 µL/min. Mobile phase consisted of 100 mM di-sodium hydrogen phosphate anhydrous (Fluka, Inc.), 1-Octanesulfonic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.), Reagent MB (ESA, Inc), and the pH was adjusted to 8.0 using phosphoric acid. Samples were passed through a Shiseido Capcell Pak C18 MGII column, 100A, 3micron, 1.5 × 75mm, and then through a solid-phase reactor (ESA, Inc.) containing acetylcholinesterase and choline oxidase at 35 °C. The resulting H2O2 was detected with a model M5040 electrochemical cell attached to a Coulochem model 5300 detector (ESA, Inc.). Chromatograms were analyzed using EasyChrome software. ACh standards were prepared in ACSF. Twenty microliters of each sample was injected. All standards were run in duplicate. Quantity of ACh was determined by measuring area under the ACh peak. This assay was able to detect as little as 30 fmol of ACh per 20 µL sample. Values from in vivo dialysates were then corrected for probe recovery and expressed as picomoles per 20 µl sample. The two samples collected prior to the switch to high potassium were averaged as an estimate of basal ACh release. Subsequent samples were used to calculate percent change in ACh release relative to baseline for each rat. In this way, each rat served as its own control for estimating potassium-stimulated release. Percent change that was calculated from the two samples collected over 60 minutes after switching to high potassium were averaged as a measure of percent change from basal release during the 60 minute period. Remaining samples were evaluated to verify that release declined after switching back to low potassium. This was done for each rat. Average basal and potassium-stimulated release was then calculated for each treatment group. Effects of treatment on basal and potassium-stimulated release were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test.

Results

Characterization of GPR30 Expression in the Forebrain

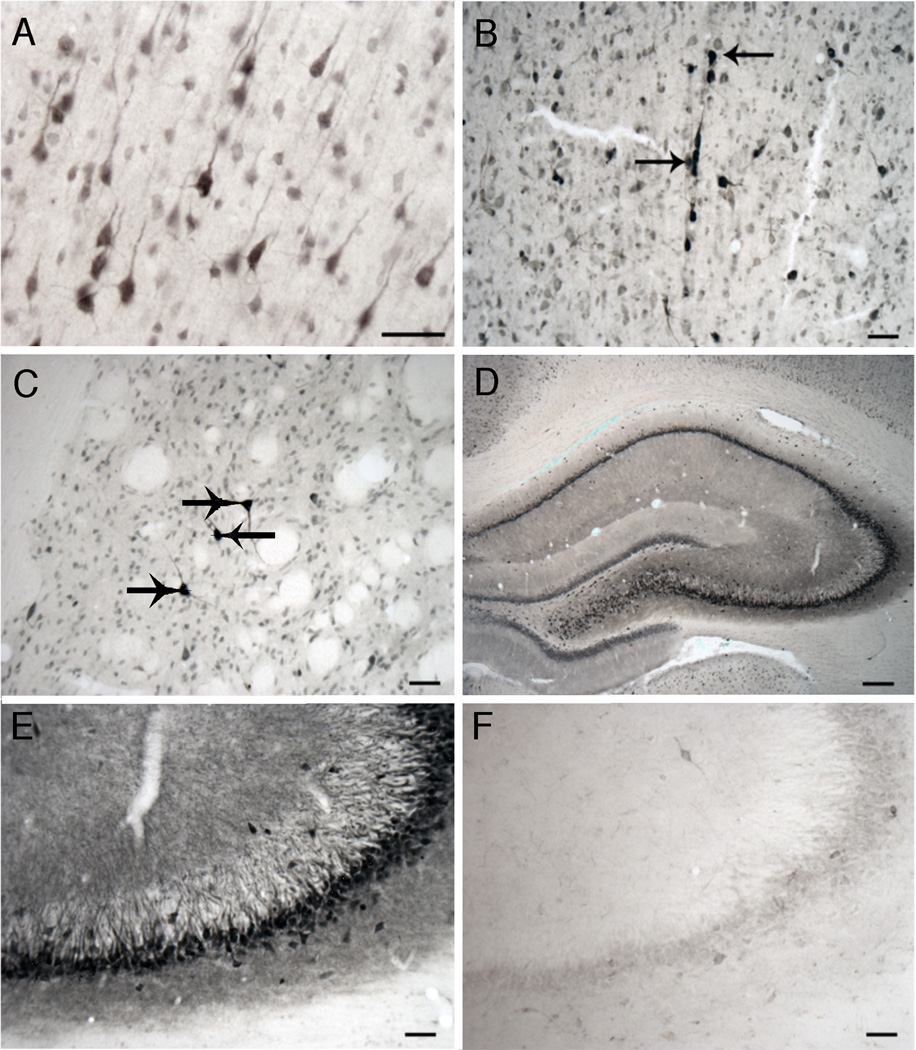

GPR30-IR was detected in many regions of the rat forebrain including the hippocampus, septum, frontal cortex, striatum, and nucleus basalis (Figure 2). Strong staining was seen in the cytoplasm and in some processes. Some cells were more strongly labeled than others. Staining was particularly strong in presumptive cholinergic cell groups (Figure 2B and 2C). Staining was greatly reduced in sections incubated with the GPR30 antibody plus 10 µg/mL C-terminal blocking peptide (Figure 2F). Staining was not observed in sections that received no primary antibody.

Figure 2.

Photomicrographs illustrating GPR30 like immunoreactivity in different forebrain regions. A) Frontal Cortex. B) Medial Septum. C) Striatum. D) Hippocampus. E) CA3 Region of Hippocampus. F) CA3 Region that was incubated with GPR30 antibody plus C-terminal peptide. Scale bar = 50 µm in panels A–C, E, and F. Scale bar = 200 µm in panel D. Arrows point to several intensely labeled cells in regions containing cholinergic nuclei.

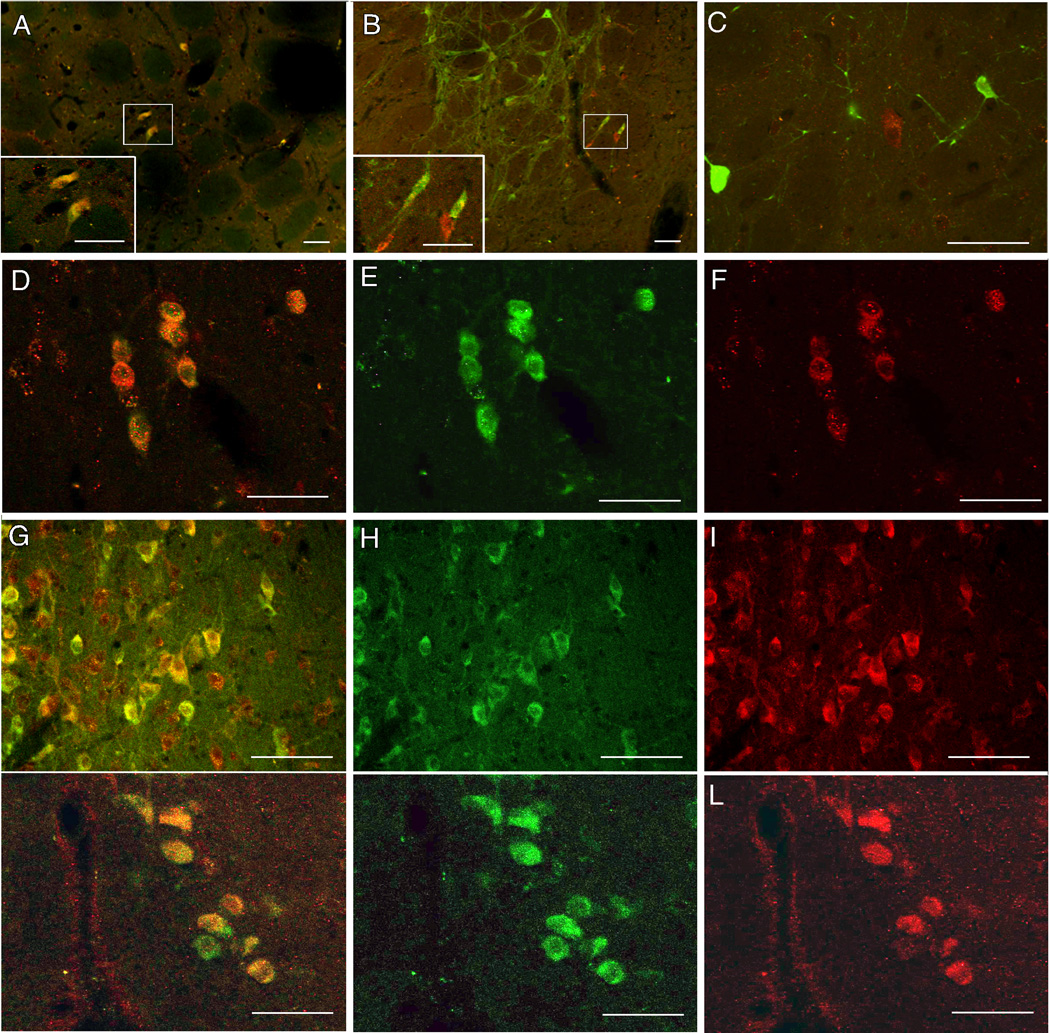

Co-localization of GPR30-IR with ChAT or Parv

Detection of GPR30-IR in ChAT- and Parv-labeled cells is shown in Figure 3. No staining was seen in control sections for which primary antibodies were omitted (not shown). Many ChAT-GPR30 double-labeled cells were detected in regions containing basal forebrain cholinergic neurons. In comparison, Parv-GPR30 double-labeled cells were less abundant. In the MS and STR, nearly all of the ChAT-IR cells detected also contained GPR30-IR (95% and 99%). In the VDB, HDB, and STR, 62%, 68%, and 81%, of ChAT-IR cells also contained GPR30-IR. In contrast, only 19%, 35%, 42%, and 0.4% of Parv-IR cells in the MS, VDB, HDB, and STR contained GPR30-IR. These results are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Confocal images illustrating co-localization of GPR30-IR with ChAT (A, D, G, J), as well as examples of Parv-labeled cells lacking GPR30-IR (B, C). Panels A and B show sections through the striatum, C–F show sections through the medial septum, G–I show sections through the nucleus basalis, and J–L show sections through the vertical limb of the diagonal band of Broca. The insets in panels A and B show indicated neurons at higher magnification. Panels E and F are unmerged images of D. H and I are unmerged images of G. K and L are unmerge images of J. ChAT- or Parv-staining is green. GPR30-IR staining is red. Double-labeled cells appear orange/yellow. Scale bar = 50 microns in A–F and J–L, and 80 microns in G–I.

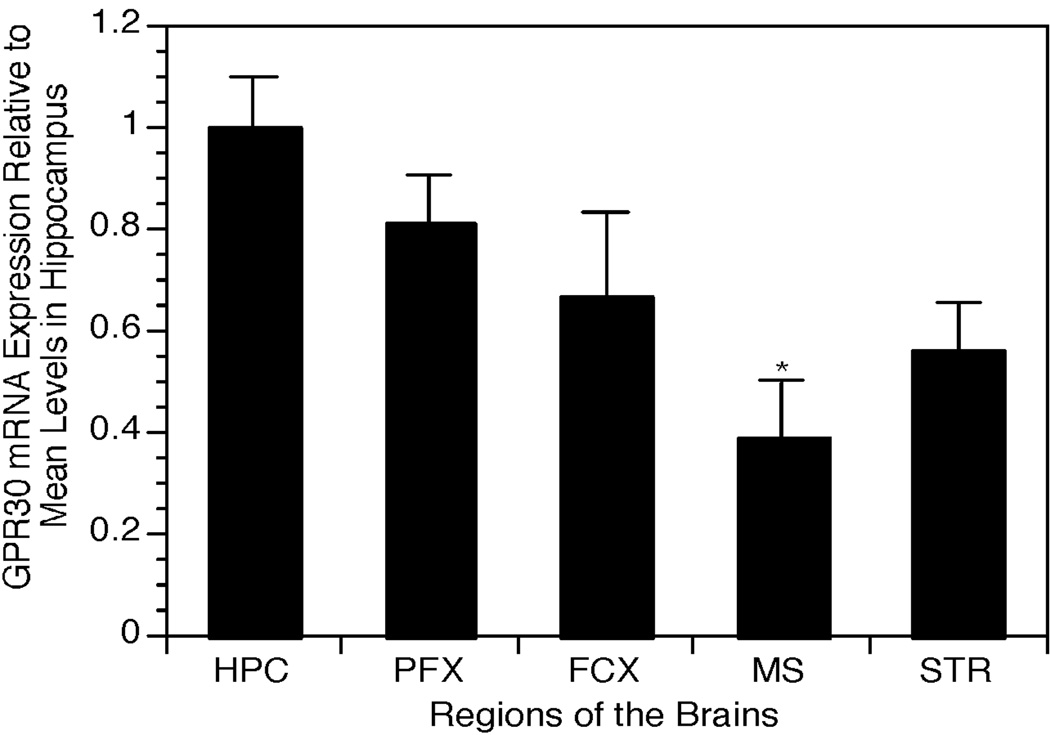

GPR30 mRNA detection

RT-PCR was used to verify the presence of GPR30 mRNA in the regions of interest. Results confirmed that GPR30 mRNA could be detected in each region analyzed. Relative levels differed depending on the region of interest. The highest levels were detected in the hippocampus, whereas lowest levels were detected in the septum and striatum (Figure 4). Post-hoc analysis confirmed that levels of GPR30 mRNA in the septum were significantly lower than in the hippocampus (p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Bar graph comparing relative GPR30 mRNA levels in different forebrain regions. Bars represent mean levels of GPR30 mRNA± SEM relative to mean levels in the hippocampus. HPC: hippocampus. PFX: prefrontal cortex. FCX: frontal cortex. MS: medial septum. STR: striatum. n=3. * p<0.05

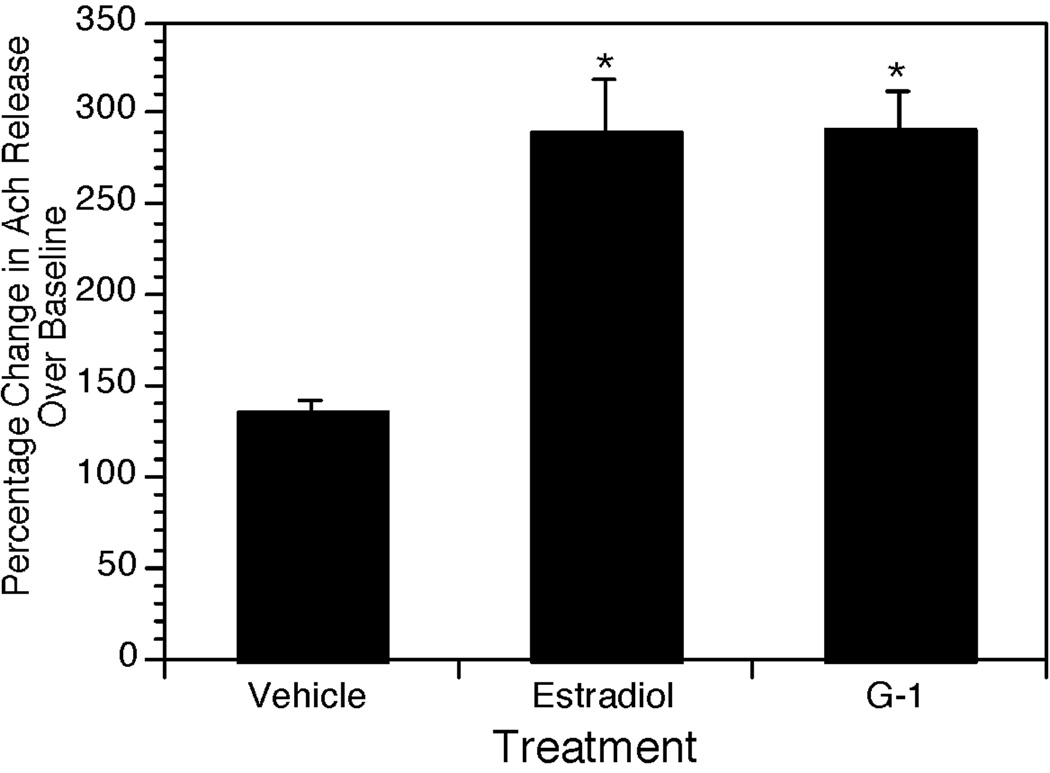

Effects of G-1 and E2 on ACh Release

Treatment with either G-1 or E2 had no significant effect on basal extracellular levels of ACh in the hippocampus. Basal levels were 0.38±0.02, 0.34±0.03, and 0.46±0.03 pmol/20µL for controls, G-1 and E2-treated rats respectively. In contrast, treatment with G-1 or E2 produced substantial increases in potassium-stimulated ACh release (Figure 5). The average percent change relative to baseline was 135.4±6.8% for controls, versus 290.7±21.2% and 289.8±28.9% for G-1 and E2-treated groups. ANOVA revealed a significant effect of Treatment (F[2,9]=4.50, p < 0.04). Post-hoc analysis revealed that E2 and G-1 treatments differed significantly from OVX controls but not from each other. Following return to low potassium, levels of extracellular acetylcholine declined (not shown); however our sampling scheme (2 samples collected over 60 minutes) often was not sufficient to confirm decline to basal levels.

Figure 5.

Bar graph showing percent change in ACh release in response to elevated potassium. Bars represent average percentage change from baseline ± SEM. * p <0.05 relative to vehicle treated animals. n=4 per group.

Discussion

The data show that GPR30 is expressed in many regions of the forebrain that are important for learning and memory including the hippocampus, frontal cortex, striatum, and in basal forebrain cholinergic nuclei. These findings are consistent with and augment previous studies showing significant GPR30 expression in hippocampus, and in specific regions of the hypothalamus and spinal cord (Brailoiu et al., 2007; Dun et al., 2009). Our co-localization studies show that the majority of cholinergic neurons in the MS, DBB, and NBM contain GPR30-IR. In addition, treatment with G-1, a selective GPR30 agonist, produced a nearly three-fold increase in potassium-stimulated ACh release in the hippocampus, similar to E2. As mentioned above, the same dose of G-1 or E2 was shown to enhance acquisition of a delayed matching-to-position T-maze task in rats (Hammond et al., 2009), and cholinergic denervation of the hippocampus blocks the effects of E2 on this task (Gibbs, 2007). Taken together, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that activation of GPR30 can mediate effects of E2 on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons with corresponding effects on cognitive performance.

The role of different ERs in Mediating Effects of Estradiol on Cholinergic Neurons

Although the current study shows that the majority of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain contain GPR30-IR, a subset (~30%) of these neurons also contain ERα (Mufson et al., 1999; Shughrue et al., 2000). In fact, one study reported that as many as 60% of cholinergic neurons in the MS contain ERα-IR (Miettinen et al., 2002), whereas very few express ERβ. The fact that G-1 had the same effect on potassium-stimulated ACh release as E2 suggests that activation of GPR30 alone may be sufficient to mediate this effect. Cell culture studies show that G-1 does not bind to ERα or ERβ, produces effects in cells expressing GPR30 but lacking ERα and ERβ, and does not produce effects in cells lacking GPR30 (Bologa et al., 2006). This suggests that the effects of G-1 on ACh release are not due to G-1-mediated activation of ERα or ERβ. In the SKBR3 cell line, which expresses GPR30 but not ERα or ERβ, knockdown of GPR30 decreases E2 binding by 80% and blocks E2 signaling (Thomas et al., 2005), suggesting that GPR30 alone can mediate E2 effects. These results are somewhat controversial. Results showing a lack of GPR30 involvement in E2 signaling in mouse endothelial cells as well as SKBR3 cells also has been reported (Pedram et al., 2006), although there is evidence for a direct role of GPR30 signaling in keratinocytes (Kanda and Watanabe, 2004). It remains to be determined whether GPR30 alone is sufficient to account for the effects of estradiol on ACh release.

Even if GPR30 plays a significant role (as suspected) in mediating effects of E2 on ACh release, this does not mean that all effects of E2 on basal forebrain cholinergic neurons are mediated by GPR30. Szego et al. (2006) showed that E2 administered either in vivo or in vitro induces pCREB in approximately 30% of the cholinergic neurons in the MS and substantia innominata of ovariectomized mice, that this involved activation of the MAP kinase pathway, and that this occurred in ERβ knock-out, but not ERα knock-out mice. These data suggest that E2 can directly affect a subpopulation of cholinergic neurons in MS and substantia innominata via ERα. Whether E2 activation of MAPK and CREB involve activation of GPR30 is not yet known. The fact that effects were not observed in ERβ knock-out mice, however, suggests that activation of GPR30 alone cannot be sufficient. One possibility is that activation of GPR30 does not play a role in mediating these effects. Another possibility is that signaling via ERα cooperates with signaling via GPR30 to mediate effects on cholinergic function, perhaps via different signaling pathways. For example, the MCF-7 cell line expresses both GPR30 and ERα, and some studies show that E2 signaling via either receptor can induce c-fos expression in these cells (Maggiolini et al., 2004). Further studies are needed to identify the extent to which GPR30 is responsible for mediating the effects of E2 on basal forebrain cholinergic function. The recent development of a selective GPR30 antagonist (G-15) will be useful in this regard.

Cellular localization of GPR30 and mechanisms of signaling

Currently there are conflicting results regarding the cellular localization (cell surface versus endoplasmic reticulum) of GPR30 (Prossnitz et al., 2007). Previous studies using confocal fluorescence microscopy reported localization of GPR30 to the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi (Revankar, 2005; Filardo et al., 2006). Others have reported GPR30 localizes to the cell surface (Thomas et al., 2005; Funakoshi et al., 2006), as it co-localizes with concanavalin A, a plasma membrane marker (Filardo et al., 2007). In our studies, GPR30 appeared to be located both on the cell surface and in the cytoplasm, which is consistent with localization on the plasma membrane and endoplasmic reticulum. It should be emphasized, however, that our analysis was not designed to isolate expression within any given cellular compartment. There may be differences in the intracellular distribution of GPR30 based on cell type. For example, GPR30-IR in endothelial cells lining the third ventricle appeared to localize differently within the cells compared with GPR30-IR in neurons (not shown). Further work is underway to better identify the subcellular localization of GPR30-IR within specific cells in the brain.

With regards to signaling, GPR30 functions as a classic G-protein coupled receptor. Studies utilizing breast cancer cells demonstrated GPR30-mediated E2 signaling through a pertusis toxin-sensitive pathway (indicating the involvement of Gi/o G-protein complex) that involves the activation matrix metalloproteinase, causing release of heparin-bound epidermal growth factor (EGF) which then binds to EGF receptors on the cell surface and activates MAPK signaling (Filardo et al., 2000). In these cells, administration of an EGF receptor inhibitor blocked the effects of E2, consistent with GPR30 signaling (Filardo et al., 2000). Subsequent studies identified a second phase of GPR30 signaling that involved activation of adenylyl cyclase and a cAMP-mediated attenuation of EGF-mediated activation of Erk (Filardo et al., 2002). Whether GPR30 utilizes the same signaling processes in brain, and whether specific E2 effects in the brain are blocked by EGF receptor antagonists, needs to be evaluated.

Involvement of GPR30 in Mediating Estradiol Effects in Brain

These findings support the growing body of evidence that GPR30 may have important actions in the brain. For example, G-1 has been shown to cause increases in intracellular calcium concentrations in dissociated and cultured hypothalamic rat neurons (Brailoiu et al., 2007; Lebesgue et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2010). G-1 also has been shown to increase the firing activity of hypothalamic neurons containing luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) (Noel et al., 2009), which suggests that GPR30 plays a role in estrogen-mediated regulation of LHRH release. Moreover, G-15 (GPR30-selective antagonist) has recently been shown to attenuate the effects of G-1 and E2 in a mouse model of depression (Dennis et al., 2009), suggesting that GPR30 plays a role in estrogen-mediated effects on mood.

While the focus of this study was on cholinergic neurons, it should be noted that most of the cells containing GPR30-IR in the forebrain were not cholinergic. Many of these cells have not been phenotypically identified; however, we did find that a subset of parvalbumin-IR neurons in specific regions of the forebrain also contain GPR30-IR. In the medial septum, parvalbumin-containing neurons are GABAergic. They synapse onto the dendrites of cholinergic neurons in the septum/diagonal band as well as project to the hippocampal formation (Leranth and Frotscher, 1989). In addition, these neurons are excited by muscarinic agonists (Wu et al., 2000), and it has been shown that cholinergic neurons in the medial septum provide an excitatory drive to the GABAergic projections (Alreja et al., 2000). Like the cholinergic neurons, these GABAergic projections have been shown to play a role in specific cognitive processes (Zarrindast et al., 2002). Hence, it is possible that activation of GPR30 on GABAergic neurons in the MS contribute to effects of G-1 and E2 on cognitive performance.

GPR30-IR also was detected in many regions of the hippocampus and frontal cortex, which also are critical for learning and memory. In the hippocampus, estradiol has many effects on connectivity, synaptic plasticity, and function (Woolley, 2007; Spencer et al., 2008). Among these effects are a significant increase in the number of dendritic spines and NMDA receptors on the apical dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells, which are thought to contribute to estrogen effects on memory (Sandstrom and Williams, 2001; Sandstrom and Williams, 2004). Notably, these effects also are dependent on cholinergic afferents (Daniel and Dohanich, 2001; Lam and Leranth, 2003). In the frontal cortex, ovariectomy decreases and estradiol increases dendritic spine density in specific regions of the cortex in rats and nonhuman primates(Tang et al., 2004; Hao et al., 2006; Hajszan et al., 2007), which likewise has been associated with effects on memory (Li et al., 2004; Wallace et al., 2006; Wallace et al., 2007). The extent to which GPR30 plays a role in mediating these effects is currently unknown and needs to be investigated.

Conclusions

GPR30-IR is expressed in many regions of the rat forebrain. In addition, the vast majority of cholinergic neurons in the forebrain express GPR30-IR, and we provide evidence that activation of GPR30 can enhance ACh release in the hippocampus similar to estradiol. This supports the hypothesis that GPR30 plays a role in mediating the effects of E2 on basal forebrain cholinergic function. Studies show that cholinergic inputs to the hippocampus and cerebral cortex play a critical role in mediating effects of E2 on cognitive performance (Gibbs, 2010). These cholinergic projections also are impaired by aging and in association with Alzheimer’s disease (Linstow and Platt, 1999; Smith et al., 1999; Lanari et al., 2006). Recently, we showed that G-1 enhanced acquisition of a DMP spatial learning task similar to estradiol (Hammond et al., 2009), which is consistent with the effects of G-1 on ACh release. Likewise, GPR30 agonists may be an effective therapy for reducing cognitive decline associated with aging and Alzheimer’s related dementia. Studies which focus on defining the role of GPR30 in mediating estradiol effects on cholinergic neurons as well as elsewhere in the brain, and on the mechanisms by which GPR30 activation elicits these effects, currently are underway.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alreja M, Wu M, Liu W, Atkins JB, Leranth C, Shanabrough M. Muscarinic tone sustains impulse flow in the septohippocampal GABA but not cholinergic pathway: implications for learning and memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20(21):8103–8110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08103.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohacek J, Bearl AM, Daniel JM. Long-term ovarian hormone deprivation alters the ability of subsequent oestradiol replacement to regulate choline acetyltransferase protein levels in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of middle-aged rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20(8):1023–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologa CG, Revankar CM, Young SM, Edwards BS, Arterburn JB, Kiselyov AS, Parker MA, Tkachenko SE, Savchuck NP, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. Virtual and biomolecular screening converge on a selective agonist for GPR30. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2(4):207–212. doi: 10.1038/nchembio775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailoiu E, Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Mizuo K, Sklar LA, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER, Dun NJ. Distribution and characterization of estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 in the rat central nervous system. J Endocrinol. 2007;193(2):311–321. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel JM, Dohanich GP. Acetylcholine mediates the estrogen-induced increase in NMDA receptor binding in CA1 of the hippocampus and the associated improvement in working memory. J. Neurosci. 2001;21(17):6949–6956. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06949.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis MK, Burai R, Ramesh C, Petrie WK, Alcon SN, Nayak TK, Bologa CG, Leitao A, Brailoiu E, Deliu E, Dun NJ, Sklar LA, Hathaway HJ, Arterburn JB, Oprea TI, Prossnitz ER. In vivo effects of a GPR30 antagonist. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(6):421–427. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas J, Hancur-Bucci C, Naylor M, Sites C, Newhouse P. Estrogen treatment effects on anticholinergic-induced cognitive dysfunction in normal postmenopausal women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(9):2065–2078. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dun SL, Brailoiu GC, Gao X, Brailoiu E, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER, Oprea TI, Dun NJ. Expression of estrogen receptor GPR30 in the rat spinal cord and in autonomic and sensory ganglia. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(7):1610–1619. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fader AJ, Hendricson AW, Dohanich GP. Estrogen Improves Performance of Reinforced T-Maze Alternation and Prevents the Amnestic Effects of Scopolamine Administered Systemically or Intrahippocampally. Neurobiol. Learning and Mem. 1998;69(3):225–240. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fader AJ, Johnson PEM, Dohanich GP. Estrogen improves working but not reference memory and prevents amnestic effects of scopolamine on a radial-arm maze. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1999;62(4):711–717. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo E, Quinn J, Pang Y, Graeber C, Shaw S, Dong J, Thomas P. Activation of the novel estrogen receptor G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) at the plasma membrane. Endocrinology. 2007;148(7):3236–3245. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Graeber CT, Quinn JA, Resnick MB, Giri D, DeLellis RA, Steinhoff MM, Sabo E. Distribution of GPR30, a seven membrane-spanning estrogen receptor, in primary breast cancer and its association with clinicopathologic determinants of tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(21):6359–6366. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton AR., Jr Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14(10):1649–1660. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Frackelton AR, Jr, Bland KI. Estrogen action via the G protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: stimulation of adenylyl cyclase and cAMP-mediated attenuation of the epidermal growth factor receptor-to-MAPK signaling axis. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(1):70–84. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.1.0758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund TF. GABAergic septohippocampal neurons contain parvalbumin. Brain Res. 1989;478(2):375–381. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)91520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funakoshi T, Yanai A, Shinoda K, Kawano MM, Mizukami Y. G protein-coupled receptor 30 is an estrogen receptor in the plasma membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346(3):904–910. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabor R, Nagle R, Johnson DA, Gibbs RB. Estrogen enhances potassium-stimulated acetylcholine release in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 2003;962(1–2):244–247. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Fluctuations in relative levels of choline acetyltransferase mRNA in different regions of the rat basal forebrain across the estrous cycle: effects of estrogen and progesterone. J Neurosci. 1996;16(3):1049–1055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01049.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Estrogen replacement enhances acquisition of a spatial memory task and reduces deficits associated with hippocampal muscarinic receptor inhibition. Horm Behav. 1999;36(3):222–233. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Effects of gonadal hormone replacement on measures of basal forebrain cholinergic function. Neuroscience. 2000;101(4):931–938. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Estradiol enhances DMP acquisition via a mechanism not mediated by turning strategy but which requires intact basal forebrain cholinergic projections. Horm Behav. 2007;52(3):352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB. Estrogen Therapy and Cognition: A Review of the Cholinergic Hypothesis. Endocrine Reviews. 2010;31(2) doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0036. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs RB, Hashash A, Johnson DA. Effects of estrogen on potassium-stimulated acetylcholine release in the hippocampus and overlying cortex of adult rats. Brain Res. 1997;749(1):143–146. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01375-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajszan T, MacLusky NJ, Johansen JA, Jordan CL, Leranth C. Effects of androgens and estradiol on spine synapse formation in the prefrontal cortex of normal and testicular feminization mutant male rats. Endocrinology. 2007;148(5):1963–1967. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond R, Mauk R, Ninaci D, Nelson D, Gibbs RB. Chronic treatment with estrogen receptor agonists restores acquisition of a spatial learning task in young ovariectomized rats. Horm Behav. 2009;56(3):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao J, Rapp PR, Leffler AE, Leffler SR, Janssen WG, Lou W, McKay H, Roberts JA, Wearne SL, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Estrogen alters spine number and morphology in prefrontal cortex of aged female rhesus monkeys. J Neurosci. 2006;26(9):2571–2578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3440-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda N, Watanabe S. 17beta-estradiol stimulates the growth of human keratinocytes by inducing cyclin D2 expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;123(2):319–328. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.12645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss J, Patel AJ, Baimbridge KG, Freund TF. Topographical localization of neurons containing parvalbumin and choline acetyltransferase in the medial septum-diagonal band region of the rat. Neuroscience. 1990;36(1):61–72. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90351-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam TT, Leranth C. Role of the medial septum diagonal band of Broca cholinergic neurons in oestrogen-induced spine synapse formation on hip{Rhodes, 1997 #13}pocampal CA1 pyramidal cells of female rats. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17(10):1997–2005. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanari A, Amenta F, Silvestrelli G, Tomassoni D, Parnetti L. Neurotransmitter deficits in behavioural and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. Mech Ageing Dev. 2006;127(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebesgue D, Traub M, De Butte-Smith M, Chen C, Zukin RS, Kelly MJ, Etgen AM. Acute administration of non-classical estrogen receptor agonists attenuates ischemia-induced hippocampal neuron loss in middle-aged female rats. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leranth C, Frotscher M. Organization of the septal region in the rat brain: cholinergic-GABAergic interconnections and the termination of hippocampo-septal fibers. J Comp Neurol. 1989;289(2):304–314. doi: 10.1002/cne.902890210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Brake WG, Romeo RD, Dunlop JC, Gordon M, Buzescu R, Magarinos AM, Allen PB, Greengard P, Luine V, McEwen BS. Estrogen alters hippocampal dendritic spine shape and enhances synaptic protein immunoreactivity and spatial memory in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(7):2185–2190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307313101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linstow Ev, Platt B. Biochemical dysfunction and memory loss: the case of Alzheimer's dementia. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999;55:601–616. doi: 10.1007/s000180050318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luine VN. Estradiol increases choline acetyltransferase activity in specific basal forebrain nuclei and projection areas of female rats. Exp Neurol. 1985;89(2):484–490. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiolini M, Vivacqua A, Fasanella G, Recchia AG, Sisci D, Pezzi V, Montanaro D, Musti AM, Picard D, Ando S. The G protein-coupled receptor GPR30 mediates c-fos up-regulation by 17beta-estradiol and phytoestrogens in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(26):27008–27016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403588200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marriott LK, Korol DL. Short-term estrogen treatment in ovariectomized rats augments hippocampal acetylcholine release during place learning. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2003;80(3):315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan PJ, Singer CA, Dorsa DM. The effects of ovariectomy and estrogen replacement on trkA and choline acetyltransferase mRNA expression in the basal forebrain of the adult female Sprague-Dawley rat. J Neurosci. 1996;16(5):1860–1865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01860.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen RA, Kalesnykas G, Koivisto EH. Estimation of the total number of cholinergic neurons containing estrogen receptor-alpha in the rat basal forebrain. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50(7):891–902. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson EJ, Cai WJ, Jaffar S, Chen EY, Stebbins G, Sendera T, Kordower JH. Estrogen receptor immunoreactivity within subregions of the rat forebrain: neuronal distribution and association with perikarya containing choline acetyltransferase. Brain Research. 1999;849(1–2):253–274. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01960-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel SD, Keen KL, Baumann DI, Filardo EJ, Terasawa E. Involvement of G protein-coupled receptor 30 (GPR30) in rapid action of estrogen in primate LHRH neurons. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23(3):349–359. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley CA, Hautamaki RD, Kelley M, Meyer EM. Effects of ovariectomy and estradiol benzoate on high affinity choline uptake, ACh synthesis, and release from rat cerebral cortical synaptosomes. Brain Res. 1987;403(2):389–392. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG. Posttraining estrogen and memory modulation. Horm Behav. 1998;34(2):126–139. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson CR, Emson PC. AChE-stained horizontal sections of the rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. J Neurosci Methods. 1980;3(2):129–149. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(80)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedram A, Razandi M, Levin ER. Nature of functional estrogen receptors at the plasma membrane. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20(9):1996–2009. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(9):e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Sklar LA. GPR30: A G protein-coupled receptor for estrogen. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;265–266:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Smith HO, Oprea TI, Sklar LA, Hathaway HJ. Estrogen signaling through the transmembrane G protein-coupled receptor GPR30. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revankar CM, Climino Daniel F, Sklar Laryy A, Arterburn Jeffrey B, Prossnitz Eric R. A Transmembrane Intracellular Estrogen Receptor Mediates Rapid Cell Signaling. Science. 2005;307(5715):1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes ME, Li PK, Flood JF, Johnson DA. Enhancement of hippocampal acetylcholine release by the neurosteroid dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate: an in vivo microdialysis study. Brain Res. 1996;733(2):284–286. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00751-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom NJ, Williams CL. Memory retention is modulated by acute estradiol and progesterone replacement. Behav Neurosci. 2001;115(2):384–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom NJ, Williams CL. Spatial memory retention is enhanced by acute and continuous estradiol replacement. Horm Behav. 2004;45(2):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shughrue PJ, Scrimo PJ, Merchenthaler I. Estrogen binding and estrogen receptor characterization (ERalpha and ERbeta) in the cholinergic neurons of the rat basal forebrain. Neuroscience. 2000;96(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00520-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Meyer EM, Simpkins JW. The effect of ovariectomy and estradiol replacement on brain-derived neurotrophic factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cortical and hippocampal brain regions of female Sprague-Dawley rats. Endocrinology. 1995;136(5):2320–2324. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DE, Roberts J, Gage FH, Tuszynski MH. Age-associated neuronal atrophy occurs in the primate brain and is reversible by growth factor gene therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(19):10893–10898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer JL, Waters EM, Romeo RD, Wood GE, Milner TA, McEwen BS. Uncovering the mechanisms of estrogen effects on hippocampal function. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29(2):219–237. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Chu Z, Moenter SM. Diurnal in vivo and rapid in vitro effects of estradiol on voltage-gated calcium channels in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. J Neurosci. 2010;30(11):3912–3923. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6256-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szego EM, Barabas K, Balog J, Szilagyi N, Korach KS, Juhasz G, Abraham IM. Estrogen induces estrogen receptor alpha-dependent cAMP response element-binding protein phosphorylation via mitogen activated protein kinase pathway in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons in vivo. J Neurosci. 2006;26(15):4104–4110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0222-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y, Janssen WG, Hao J, Roberts JA, McKay H, Lasley B, Allen PB, Greengard P, Rapp PR, Kordower JH, Hof PR, Morrison JH. Estrogen replacement increases spinophilin-immunoreactive spine number in the prefrontal cortex of female rhesus monkeys. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(2):215–223. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhg121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146(2):624–632. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M, Frankfurt M, Arellanos A, Inagaki T, Luine V. Impaired recognition memory and decreased prefrontal cortex spine density in aged female rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1097:54–57. doi: 10.1196/annals.1379.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M, Luine V, Arellanos A, Frankfurt M. Ovariectomized rats show decreased recognition memory and spine density in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. 2006;1126(1):176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:657–680. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Shanabrough M, Leranth C, Alreja M. Cholinergic excitation of septohippocampal GABA but not cholinergic neurons: implications for learning and memory. J Neurosci. 2000;20(10):3900–3908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03900.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Bakhsha A, Rostami P, Shafaghi B. Effects of intrahippocampal injection of GABAergic drugs on memory retention of passive avoidance learning in rats. J Psychopharmacol. 2002;16(4):313–319. doi: 10.1177/026988110201600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]