Abstract

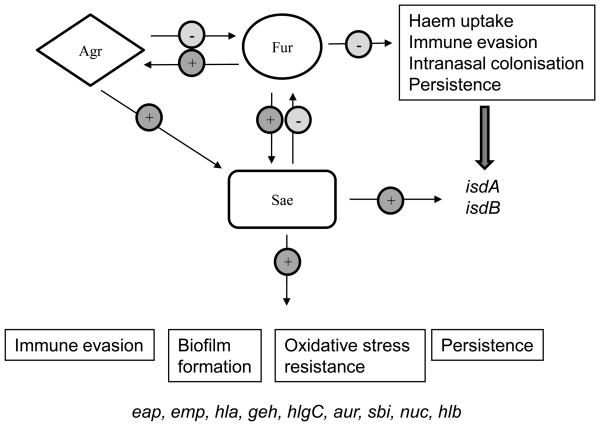

Our previous studies showed that both Sae and Fur are required for the induction of eap and emp expression in low iron. In this study, we show that expression of sae is also iron-regulated, as sae expression is activated by Fur in low iron. We also demonstrate that both Fur and Sae are required for full induction of the oxidative stress response and expression of non-covalently bound surface proteins in low-iron growth conditions. In addition, Sae is required for the induced expression of the important virulence factors isdA and isdB in low iron. Our studies also indicate that Fur is required for the induced expression of the global regulators Agr and Rot in low iron and a number of extracellular virulence factors such as the haemolysins which are also Sae- and Agr-regulated. Hence, we show that Fur is central to a complex regulatory network that is required for the induced expression of a number of important S. aureus virulence determinants in low iron.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, Iron regulation, Fur, Sae, Agr

Introduction

S. aureus is a highly adaptable organism causing a wide range of infections both in the hospital setting and more recently in the community (Diep and Otto, 2008). Its ability to cause such a range of disease is thought to be due to its capacity to produce a variety of virulence factors (Archer, 1998). Expression of these gene products is costly to the cell, and constant changes in the microenvironment mean that production of these factors has to be tightly regulated so that they are expressed only when required. This is achieved by a complex regulatory network which includes the 2 component regulators SaeRS and AgrAC (Goerke et al., 2001).

A major environmental stress encountered by bacteria during infection is severe iron limitation. Iron is an essential nutrient for various key metabolic processes and so its acquisition is vital for survival. However, excess iron is toxic and therefore free-iron levels are limited in mammalian body fluids. S. aureus has evolved to use the low availability of iron in vivo as a major environmental signal to trigger enhanced expression of some virulence determinants, including several iron acquisition mechanisms (Dale et al., 2004; Morrissey et al., 2000, 2002), adhesion to host cells (Clarke et al., 2007, 2009), and biofilm formation (Johnson et al., 2005, 2008).

The global regulator Fur mediates iron-responsive gene regulation in many bacteria, including S. aureus (Horsburgh et al., 2001; Xiong et al., 2000). Fur was originally identified as an iron-dependent repressor of genes involved in the acquisition of iron (Litwin and Calderwood, 1993). However, it has recently become apparent that S. aureus Fur not only acts as an iron-dependent repressor, but can also act positively, inducing gene expression in both low- and high-iron conditions (Horsburgh et al., 2001; Johnson et al., 2008; Morrissey et al., 2004). Our previous studies demonstrated that biofilm formation, an important virulence determinant of S. aureus, is induced in low-iron growth conditions (Johnson et al., 2005). Low-iron induced biofilm formation is dependent on the secreted, non-covalently attached cell surface proteins Eap and Emp which are positively regulated in low-iron conditions by Fur (Johnson et al., 2008). Eap and Emp are important virulence factors implicated in a number of aspects of S. aureus pathogenesis as well as biofilm formation. Both proteins promote adhesion to a broad spectrum of host proteins (Hussain et al., 2001; Palma et al., 1999). Eap is also involved in inhibition of wound healing (Athanasopoulous et al., 2006), evasion of the host immune system (Chavakis et al., 2002, 2005), and promotion of bacterial internalisation into eukaryotic cells (Haggar et al., 2003), whilst Emp is also associated with endovascular disease (Chavakis et al., 2005). Therefore Fur is essential for the induction of these important virulence determinants in low-iron conditions reflective of growth conditions in vivo. However, the mechanisms involved in the positive Fur regulation of eap and emp have not yet been defined.

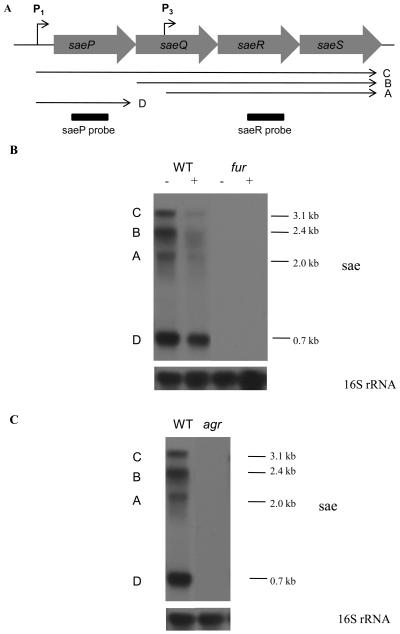

The expression of Eap and Emp is also dependent on the 2 component regulators AgrAC and SaeRS (Harraghy et al., 2005, Johnson et al., 2008). The Agr quorum sensing system is responsible for repression of cell surface proteins such as adhesins and for induced expression of exoproteins in post-exponential phase (Traber et al., 2008). The Sae regulatory system is important for expression of several toxins and immune evasion proteins (Giruado et al., 1997, Voyich et al., 2009) and is important for the response to alpha defensins and oxidative stress, which is required for neutrophil survival (Geiger et al., 2008, Voyich et al., 2005). The sae operon consists of 4 open reading frames (Fig. 1A), saeP, saeQ, saeR, and saeS (Novick and Jiang, 2003; Steinhuber et al., 2003; Goerke et al., 2005) in which saeS encodes the receptor kinase and saeR the response regulator (Giruado et al., 1997). The operon is auto-regulated (Novick and Jiang, 2003) and is responsive to a range of signals including SarA, SigB, high salt, hydrogen peroxide, and Agr in some strains (Adhikari and Novick, 2008; Geiger et al., 2008; Novick and Jiang, 2003; Steinhuber et al., 2003).

Fig. 1.

(A) Structure of the sae operon, showing positions of promoters (P1 and P3) and sae operon transcripts (A-D). (B and C) Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from S. aureus Newman and its isogenic fur and agr mutants growing exponentially in CRPMI (−) or CRPMI with 50 μM Fe2(SO4)3 (+). Ten μg of total RNA were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and hybridised with both the saeR and saeP DNA probes. The blot was then stripped and rehybridised with the 16S rRNA control probe.

In this study, we demonstrate for the first time that in low-iron conditions there is a complex overlapping regulatory network involving Sae, Agr and the iron-dependent global regulator Fur. Moreover, we show that Fur is essential for the activation of virulence gene expression through induction of the sae regulatory system.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

All strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Strains for biofilm assays and for protein and RNA extraction were cultured in iron-restricted conditions in CRPMI (Morrissey et al., 2000). Strains were plated out fresh from frozen stocks onto 6% defibrinated horse blood agar for each experiment. All cultures were incubated statically for 16 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 in air. Where indicated the medium was supplemented with 50 μM Fe2(SO4)3. 0.003% H2O2 (vol/vol) was added to Tryptic soy broth (TSB) to achieve oxidative stress. Media were supplemented with the antibiotics tetracycline (10 μg/ml) or erythromycin (10 μg/ml) where required.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strain | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Newman | Wild type | (Duthie and Lorenz., 1952) |

| Newman fur | Newman Δfur::tet | (Johnson et al., 2005) |

| Newman sae | Newman sae: : Tn917 (AS3) | (Goerke et al., 2001) |

| Newman sarA | Newman ΔsarA::ermC | (Johnson et al., 2008) |

| Newman agr | Newman Δagr::tetM | (Johnson et al., 2008) |

| Newman fur/sae | Newman Δfur::tet, sae: : Tn917 (AS3) | This study |

| SH1000 | NCTC 8325-4 with rsbU mutation repair | (Horsburgh et al., 2002) |

| 8325-4 fur | 8325-4 Δfur::tet | (Horsburgh et al., 2001) |

| SH1000 fur | SH1000 Δfur::tet | This study |

Transduction of mutations into S. aureus

The fur mutation was transduced from the fur mutant of S. aureus 8325-4 (Horsburgh et al., 2001) to SH1000 (Horsburgh et al., 2002) using phage 80α, and the mutation was confirmed by PCR using the fur specific primers FurAF and FurAR (Table 2). The sae/fur double strain was constructed by transduction of the Newman fur mutant into Newman sae::Tn917 strain (Goerke et al., 2001) as described previously (Johnson et al., 2009). Colonies containing the relevant mutation were confirmed by PCR using primers Fur1F, Fur1R, SaeRF, Sae flankR (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Description | Primer name |

Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| saeP probe | saePF | GCAGCTGGTGCTGTTATCAC |

| saePR | CGAAGATGACGTGAGC | |

| saeR probe | saeRF | GGTGCAGATGACTATG |

| saeRR | GGTATACTCGATACGACG | |

| fur RNA probe | FurF | CATCTACACGACCACATTCC |

| FurR | CGATTAAATCGCGTTAAGCAAC | |

| sae gene sequencing | Sae Flank F | GTTTATTTCAACATTTAATAGC |

| SaePR | CGAAGATGACGTGAGC | |

| Sae Int F | CGCAATGGTTGACTACGA | |

| Sae Int R | GTTTATTTCAACATTTAATAGC | |

| SaeSF | GGTGTTATCAATTAGAAGTC | |

| Sae Flank R | GAGAAGGATACCCATAAAG | |

| isdA probe | isdAF | GGATGACTATATGCAACACC |

| isdAR | GTTCTTGAGCAGTTTGTG | |

| isdB probe | isdBF | CTGTTGAGTTCCATCTTTC |

| isdBR | CTACAACATGAACAAACGG | |

| Fur mutant | FurAF | CTATCCTTTACCTTTAGCT TGGCA |

| FurAR | TTGGAAGAACGATTAAATCGC | |

| Fur mutant | Fur1F | AGGTACAGTTCACTTAGATG |

| Fur1R | CGCGCAATAGATTTAGCAG | |

| fhuA RT-PCR | fhuAF | ATGAATCGTTTGCATGGA |

| fhuAR | AATGATTGACGTCACTTTGC | |

| sstC RT-PCR | sstCF | TAAAGAAGAACGTTTCCATGGAC |

| sstCR | CTTGAAAAGTCAATTTTTGGTGC | |

| ftnA RT-PCR | ftnAF | ATGAATCGTTTGCATGGACA |

| ftnAR | TTGACGTCACTTTGCCATCT | |

| atl RT-PCR | atlF | TTAGTTACAGAGTTGTCGTCATTCCA |

| atlR | GGTAATCTAGATGCGCCGAATAA |

RNA extraction for Northern blotting

RNA was extracted from exponential (6 h) S. aureus cultures in CRPMI and analysed by northern blot as previously described (Johnson et al., 2008). Transcripts were evaluated using ImageJ 1.41 software downloaded from http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/.

Sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Cell wall and SDS surface proteins were extracted from S. aureus cells grown for 24 h in 10 ml of CRPMI as previously described (Hussain et al., 2001), except that dialysis to remove SDS was omitted (Johnson et al., 2008), and an equal volume of 2×Laemmli sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) was added to cell suspensions prior to boiling for 3 min and separating by SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as previously described (Johnson et al., 2008).

MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy analysis

Bands excised from 1D-SDS polyacrylamide gels were subjected to in-gel trypsin digestion and analysis as per standard procedures (Speicher et al., 2000) within the PNACL Proteomics Facility, University of Leicester, as described previously (Johnson et al., 2008).

Hydrogen peroxide growth assays

Bacteria were grown overnight in TSB at 37°C with shaking in air, diluted to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.05 in fresh TSB with appropriate antibiotics, and then split into duplicate cultures and incubated with shaking at 37°C for 4 h. The OD600 was measured and 0.003% H2O2 (vol/vol) was added to one of the duplicates; both were then incubated with shaking at 37°C, and the OD600 was measured 2 h after addition of H2O2.

Transcriptional profiling

S. aureus SH1000 and its Δfur mutant strain were inoculated on TSB agar and then transferred to 5 ml of defined medium (DM) (Townsend and Wilkinson., 1992) and grown at 37°C for 18 h with aeration. Each strain was then diluted 1:10 into chelex-treated (Bio-Rad) DM without iron and allowed to grow in acid-washed glassware to deplete the organisms' internal iron pools. This was used as starter culture which was diluted 20× in fresh chelex-treated DM without or with iron (100 μM FeCl3) and incubated with aeration at 37°C. Growth was monitored at OD600 in a spectrophotometer. Samples for transcriptional profiling experiments were taken at early log-phase (OD600 0.6-0.7). S. aureus SH1000 wild type served as the control, whereas the S. aureus SH1000 fur mutant was the test sample. The DNA microarray experiments were performed using 3 independently cultured sample sets to isolate the RNA, and each set was run independently to generate triplicate data. RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, labelling, and array hybridisation were carried out as described previously (Muthaiyan et al., 2008). The denatured cDNA was applied to a S. aureus genome microarray version 5.0 DNA chip (Pathogen Functional Genomic Resource Center – The Institute of Genomics Research, PFGRC-TIGR http://pfgrc.jcvi.org) under a glass slide, and hybridization was carried out overnight at 42°C. After hybridization, the slides were washed at room temperature in wash buffer I (1× SSC, 0.2% SDS) twice for 10 min, in wash buffer II (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS) once for 10 min, and in wash buffer III (0.1× SSC) twice for 10 min. The slides were dried by centrifugation at 500 rpm for 5 min.

Data analysis

Hybridization signals were scanned using Axon 4000B scanner with Acuity 4.0 software. Scans were analysed using TIGR-Spotfinder software, and the data set was normalized by applying the LOWESS algorithm using TIGR-MIDAS software (www.tigr.org/software/). Significant changes of gene expression were identified with significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) software using one class mode. SAM assigns a score to each gene on the basis of change in gene expression relative to the standard deviation of repeated measurements. A “q value” assigned to each gene corresponds to the lowest false discovery rate at which the gene is called significant (43). Three independent cultures were used to prepare RNA.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Prior to RNA isolation SH1000 and Δfur were grown in defined media in the presence and absence of iron under the same conditions as used for the transcriptional profiling. RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Protect Bacteria Mini Kit (Qiagen) and DNA removed from the samples by DNase I treatment (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's instructions. The purified RNA was quantified using the nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the integrity assessed by electrophoresis. 0.5 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's instructions. qRT-PCR was performed using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in a 7300 Fast System (Applied Biosystems) according to manufacturer's instructions. The relative levels of gene expression in the treated cells and the non-treated controls were calculated by relative quantification using 16S rRNA gene as the endogenous reference. All samples were amplified in triplicate, and the data analysis was carried out using the 7300 Fast System Software (Applied Biosystems).

Results

Expression of sae in low iron is dependent on Fur and Agr

Multiple regulators, including Fur, Sae, and Agr, are involved in the low-iron-mediated induction of eap and emp; however, it is not clear how these regulators interact or how Fur induces the expression of eap and emp. It is possible that iron/Fur regulation of eap and emp is indirect and mediated via regulation of the gene encoding the positive regulator Sae. Therefore, we investigated the iron-responsive regulation of sae transcription. Total RNA was extracted from Newman wild type and the Newman fur mutant growing exponentially in CRPMI with or without added iron. Expression of the sae operon is complex as there are 2 promoters and possible post-transcriptional modification resulting in 4 different transcripts designated A–D (Fig. 1A) (Adhikari and Novick, 2008; Giraudo et al., 2003). Therefore Northern blot analysis was carried out using a combination of 2 sae-specific probes, saeP which detects transcripts D and C, and saeR which detects transcripts A, B, and C (Adhikari and Novick, 2008). In Newman wild type, all 4 sae transcripts were decreased by the addition of iron (Fig. 1B) indicating that this important global virulence gene regulator is iron-regulated. However, in the fur mutant, no sae transcripts were detected suggesting that Fur is essential for the activation of sae transcription. Therefore, it appears that Fur acts as an activator and not a repressor of sae expression suggesting that there is another iron-dependent repressor in S. aureus other than Fur. This is the same phenotype as observed previously for low-iron and Fur-mediated regulation of eap and emp transcription (Johnson et al., 2008). These observed differences are not due to growth effects as although the addition of iron improved growth very slightly compared to iron-restricted medium, there was no overall difference in growth between the S. aureus strains in iron-restricted or iron-replete CRPMI (data not shown). Therefore, it appears that low-iron and Fur regulation of eap and emp transcription is indirect and is mediated through Fur-dependent regulation of sae which positively regulates eap and emp expression.

Northern blot analysis also showed that sae transcription in the agr mutant in low-iron medium was decreased compared to the wild type (Fig. 1C). No sae operon transcripts were detected in the agr mutant, which corresponds to the lack of exoprotein expression seen in our previous studies (Johnson et al., 2008). However, this observation is in contrast to previous studies which show that S. aureus Newman sae is not regulated by Agr because of mutation in the gene encoding the auto-activator SaeS (Adhikari and Novick, 2008; Geiger et al., 2008). DNA sequencing showed that the mutation in the saeS open reading frame was also present in the Newman isolate used in this study, which correlates with the observed increase in expression of many Sae-regulated proteins such as Eap and Emp also seen in Newman in other studies (Harraghy et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2008). Thus, in low-iron Newman sae expression is induced by Agr despite the amino acid substitution in SaeS. Therefore, these results demonstrate that under low-iron growth conditions sae expression is dependent on Fur and Agr.

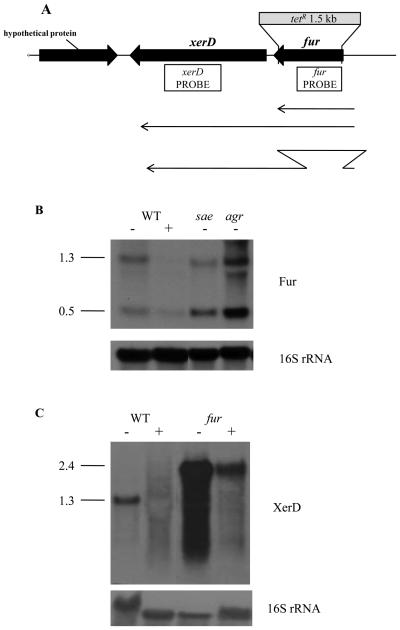

S. aureus fur is negatively regulated by Agr and Sae

We further investigated the relationship between these regulators by determining whether fur is regulated by Sae or Agr. Total RNA was extracted from Newman wild type and its isogenic Δfur, Δagr, and Δsae mutant strains growing exponentially in CRPMI with or without the addition of iron. Northern blot analysis using a fur-specific probe revealed 2 transcripts of approximately 1.3 and 0.5 kb (Fig. 2B), suggesting that fur is cotranscribed with the downstream gene xerD (Fig. 2A). Transcript levels in the wild type were significantly decreased by the addition of iron, indicating that fur expression is regulated by iron. Northern blot analysis using a xerD-specific probe detected a single iron-repressed transcript in Newman of approximately 1.3 kb, confirming that fur and xerD are cotranscribed (Fig. 2C). In the fur mutant, there was a single larger fur/xerD transcript of approximately 2.4 kb corresponding to the few remaining bases of the fur gene, the tetracycline cassette used in the construction of the fur mutant (Horsburgh et al., 2001), and the xerD gene. The presence of this transcript confirms that the fur mutation does not affect xerD expression which is supported by the fact that xerD mutation is lethal in S. aureus (Chalker et al., 2000). The level of Δfur::tet/xerD transcript was increased compared to the wild-type fur/xerD transcript, but was still repressed in high iron (Fig. 2C), which suggests that fur is auto-repressed but that, interestingly like sae (Fig. 1B), the fur/xerD operon is also iron-regulated independently of fur.

Fig. 2.

Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from S. aureus Newman and its isogenic sae, agr, and fur mutants growing exponentially in CRPMI (−) or CRPMI with 50 μM Fe2(SO4)3 (+). Ten μg of total RNA were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and hybridised with (B) fur and (C) xerD DNA probes. The blots were then stripped and rehybridised with the 16s rRNA control probe. (A) Genetic organisation of fur xerD operon.

Northern blot analysis also demonstrated that the 0.5-kb fur transcript is regulated by Agr and Sae (Fig. 2B). Densitometry analysis showed that the 0.5-kb transcript was increased 4-fold in the agr mutant and 2-fold (+/− 0.216) in the sae mutant, indicating that Agr and to a lesser extent Sae repress Fur transcription. Thus, there appears to be a complex, regulatory feedback system encompassing Fur, Sae, and Agr.

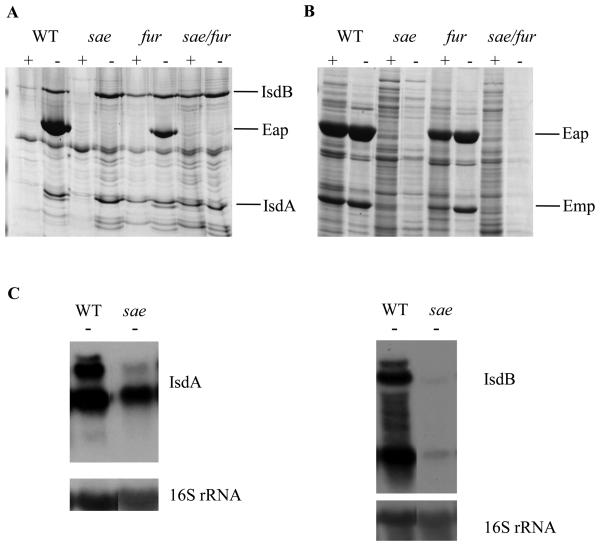

The Fur and Sae regulons overlap, and both regulators are required for oxidative stress resistance

To determine the global effect of combining the sae and fur mutations, proteins were prepared from cell wall and SDS surface extracts from S. aureus Newman wild type and the isogenic sae, fur, and sae/fur mutants grown in CRPMI with and without iron. In the cell wall extracts, 3 major proteins were shown to be induced in low iron; these were identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy as IsdB (FrpB), IsdA (FrpA), and Eap (Fig. 3A). IsdA and IsdB are involved in haem uptake and have characteristic LPXTG motifs that covalently anchor them to the cell surface (Mazmanian et al., 2003), whereas Eap is non-covalently attached to the cell surface (McGavin et al., 1993). The isdA and isdB genes contain Fur-binding consensus sequences in their promoters and are classically regulated by Fur (Morrissey et al., 2002), whereas eap transcription is positively regulated by Fur in low iron but has no obvious Fur-binding consensus sequence in its promoter (Johnson et al., 2008). This Fur regulation is confirmed by the observation that in the fur mutant IsdA and IsdB are constitutively expressed, whereas there is a decrease in Eap levels (Fig. 3A). In the sae and fur/sae mutants, no Eap protein could be detected, therefore showing that eap is positively regulated by both Sae and Fur as seen previously (Johnson et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

(A) Cell wall. (B) SDS surface extract obtained from S. aureus Newman and its isogenic mutants sae, fur, and sae/fur grown for 16 h in iron-restricted CRPMI (−) or CRPMI with 50 μM Fe2 (SO4)3 (+) added to give iron-replete growth conditions. All lanes are equivalently loaded. Gels presented are representative of experiments repeated at least 3 times using protein extracted from post-exponential phase cultures grown on different days with similar results observed each time. (C) Northern blot analysis of total RNA prepared from S. aureus Newman and its isogenic sae mutant growing exponentially in CRPMI (−). Ten μg of total RNA were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and hybridised with (C) isdA or isdB DNA probes. The blots were then stripped and rehybridised with the 16S rRNA control probe.

Interestingly isdA and isdB expression is also regulated by Sae at the transcriptional level. Northern blot analysis of total RNA extracted from Newman wild type and Δsae mutant strains growing exponentially in CRPMI showed that both isdA and isdB expression is decreased in Newman sae compared to Newman wild type (Fig. 3C). Therefore, these results show that components of the Fur regulon are positively regulated by Sae.

Overlap of the Fur and Sae regulons is further demonstrated by the SDS surface extracts as there are very few proteins expressed in low-iron growth conditions in the sae fur double mutant compared to the single sae and fur mutants (Fig. 3B). There is also differential regulation of a number of SDS surface extract proteins in the sae fur mutant compared to the single mutants (Fig. 3B). As shown previously (Johnson et al., 2008), Eap levels are lower in the SDS surface protein extracts of the fur mutant and absent in those of the sae and sae fur mutants (Fig. 3B). These results therefore suggest that the Sae and Fur regulons overlap and have a significant effect on global protein expression.

Both Fur and Sae have been implicated in oxidative stress resistance (Geiger et al., 2008; Horsburgh et al., 2001; Morrissey et al., 2004), therefore to further investigate the combined effect of these regulators H2O2 was added to one of duplicate cultures of S. aureus Newman wild type and isogenic fur, sae, or fur/sae mutant strains growing exponentially in TSB medium. A rich medium under aeration was used to ensure that quantifiable levels of oxidative stress could be assayed as all strains were hypersensitive to H2O2 in the nutrient-deficient medium CRPMI, and therefore reproducible results could not be obtained. Addition of H2O2 decreased the growth of all strains except the sae mutant which showed a 1% decrease in growth (P=0.003) compared to untreated control. Newman wild type demonstrated a 10% decrease in growth, whereas the fur mutant strain showed a 35% decrease in growth after the addition of H2O2 (P=0.0001). However, the fur sae double mutant was significantly more sensitive to H2O2 than any of the other strains as it showed a 70% decrease in growth (P=0.0001). Therefore, both Sae and Fur are required for full induction of the S. aureus oxidative stress response.

S. aureus Fur is required for the expression of a number of Sae- and Agr-regulated virulence factors in low iron

Previous transcriptional profiling has shown that Sae is a global regulator affecting the expression of a vast array of genes (Voyich et al., 2005, 2008), however, no transcriptional profiling studies have been published to date detailing the role of Fur in global gene expression in S. aureus. To determine the role of Fur in S. aureus gene expression in iron-replete conditions SH1000 wild type and fur mutant strains were grown in DM with 100 μM FeCl3. SH1000 was used in the microarray studies to begin to address iron and Fur global regulation conservation between strains as many previous global iron regulation studies have been done in Newman. Total RNA was extracted from exponentially growing staphylococci. cDNA samples were hybridised with the PFGRC S. aureus genomic microarray. After applying statistical evidence with a ≥2.0-fold difference as the threshold change and a P value less than 0.05, microarray analysis showed that 134 genes were up-regulated and 76 genes were down-regulated in the fur mutant compared to the wild type in iron-replete conditions (Table S1).

Fur is normally an active repressor in the presence of iron and so genes de-repressed in the fur mutant are candidate members of the classical Fur regulon. Therefore, not surprisingly many known Fur-regulated genes such as the iron acquisition systems and siderophore biosynthesis genes were up-regulated in the fur mutant compared to the wild type (Table 3) (Delany et al., 2004; Morrissey et al., 2000). Conversely, the ferritin (ftnA) and catalase (katA) genes were repressed in the fur mutant compared to the wild type, which was also expected as these genes are known to be positively regulated by Fur (Horsburgh et al., 2001; Morrissey et al., 2004). These results have been validated by qRT-PCR (Table 4) and are in agreement with the literature and our previous studies (Morrissey et al., 2000, 2004), and therefore these microarray results are representative of the S. aureus Fur regulon in iron-replete conditions. Other genes de-repressed in the fur mutant in iron-replete conditions include the capsule synthesis genes cap5D, cap5G, and capH and the purine ribonucleotide biosynthesis genes purE, K, Q, C, and L (Table S1), which is consistent with previous studies demonstrating capsule synthesis being iron-regulated (Lee et al., 1993). Genes down-regulated in the fur mutant in iron-replete conditions include a number of regulators such as srrA and SACOL2531, which encodes a putative transcriptional regulator of the MarR family (Table S1). Hence S. aureus Fur has a global effect on iron-regulated gene expression which encompasses many aspects of staphylococcal physiology and virulence in addition to the acquisition and storage of iron.

Table 3.

Genes with differential expression in fur mutant compared to wild type in high iron growth conditions

| Gene | Description | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Iron acquisition and storage | ||

|

| ||

| htsB | Iron-compound binding protein | 10.6 |

| htsA | Iron-compound permease protein | 4.0 |

| fhuD | Ferrichrome-binding protein | 7.9 |

| isdI | Heam mono-oxygenase | 5.8 |

| isdA | Heam-binding protein | 4.5 |

| sstC | Iron transport ATP-binding protein | 3.1 |

| fhuB | Ferrichrome transport permease protein | 2.6 |

| fhuG | Ferrichrome transport permease protein | 2.3 |

| htsC | Heme transport system permease | 2.0 |

| htsB | Heme transport system permease | 2.4 |

| sbnB | Siderophore biosynthesis gene | 17.5 |

| sbnE | Siderophore biosynthesis gene | 5.3 |

| sbnF | Siderophore biosynthesis gene | 25.9 |

| sbnG | Siderophore biosynthesis gene | 15.9 |

| sbnH | Siderophore biosynthesis gene | 23.6 |

| ftnA | Ferritin | −11.4 |

| katA | Catalase | −2.5 |

Table 4.

qRT-PCR results showing differentially expressed SH1000 genes in response to iron starvation

| Gene | Fold value | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| fhuA | 2.1 | 0.083 |

| sstC | 3.1 | 0.009 |

| ftnA | −1.8 | 0.058 |

| Atl | 8.2 | 0.088 |

To investigate the global role of Fur in S. aureus gene expression in low-iron conditions, SH1000 wild type and fur mutant strains were grown in chelex-treated DM, and microarray analysis was conducted as described above. This transcriptional profiling showed that 35 genes were up-regulated and 90 genes were down-regulated in the SH1000 fur mutant compared to the wild type in low-iron conditions (Tables 5, 6, and S2). The transcriptional profiling confirmed our previous results (Johnson et al., 2008; Fig. 1B) and demonstrated that Fur is required for induced expression of sae and eap in SH1000 as well as Newman, as the expression of both genes was decreased in the SH1000 fur mutant compared to the wild type (Tables 5 and 6). Therefore, positive regulation of sae by Fur occurs in S. aureus in different media and strains independently of the saeS mutation. Therefore it is likely that it is a general regulatory response. Furthermore, transcriptional profiling showed that the expression of a number of other Sae-regulated genes was also repressed in the fur mutant compared to the wild type including the staphylococcal nuclease (nuc), glycerol ester hydrolase (geh), and the α, β, and γ-haemolysin genes (Table 5). Therefore, Fur is required for the induced transcription of a number of important virulence factors in low-iron growth conditions many of which are also Sae-regulated, a finding that is also in agreement with our proteomic data in Newman (Fig. 3A).

Table 5.

Genes with differential expression in fur mutant compared to wild type in low-iron growth conditions

| Gene | Description | Fold change |

Positively regulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exoproteins/virulence factors | |||

|

| |||

| sbi | IgG-binding protein SBI | −5.9 | Sae |

| aur | Zinc metalloproteinase aureolysin | −5.2 | AgrA |

| eap | Extracellular adherence protein | −4.3 | Sae |

| geh | Glycerol ester hydrolase | −3.4 | Sae, AgrA |

| sspB2 | Cysteine protease precursor | −3.0 | |

| hla | α-haemolysin | −2.4 | Sae, AgrA |

| hlgC | γ-haemolysin, C component | −2.4 | Sae, AgrA |

| hlb | β-haemolysin | −2.1 | Sae |

| nuc | Staphylococcal nuclease | −2.4 | Sae |

| atl | Bifunctional autolysin | 2.6 | |

| lytM | Peptidoglycan hydrolase | 2.6 | |

| rpoC | RNA polymerase | −2.3 | |

Table 6.

Genes with differential expression in fur mutant compared to wild type in low-iron growth conditions

| Gene | Description | Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| Regulators | ||

|

| ||

| saeR | Response regulator SaeR | −2.9 |

| saeS | Sensor histidine kinase SaeS | −2.3 |

| agrA | Accessory gene sensor histidine kinase | −2.0 |

| rot | Repressor of toxins | −2.4 |

However, the transcriptional profiling revealed that Sae is not the only S. aureus global regulator which requires Fur for induced expression in low iron, as the transcript levels of agrA and rot (repressor of toxins) were also decreased in the fur mutant in low iron compared to the wild type (Table 6). Furthermore, a number of the virulence factors shown to be positively regulated by Fur are also regulated by Agr as well as Sae (Table 5). Therefore, in low-iron growth conditions S. aureus Fur is required for the expression of 3 major global virulence gene regulators, Sae, Agr, and Rot, and hence Fur is important for the expression of a diverse range of important virulence determinants (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Model of a regulatory network involving Fur, Sae, and Agr showing that Fur is a central regulator of virulence gene expression. Positive and negative regulatory pathways are indicated with either a + or −, respectively.

Discussion

In this study, we show for the first time that Fur is central to a complex overlapping regulatory network, also involving the global regulators Sae and Agr, that is required for the induced expression of a number of important S. aureus virulence determinants (Fig. 4). Our previous studies showed that both Sae and Fur are required for the induction of eap and emp expression in low iron. In this study, we show that expression of sae is also iron-regulated, as sae is induced by Fur in low iron. We also demonstrate that both Fur and Sae are required for full induction of the oxidative stress response and expression of non-covalently bound surface proteins in low-iron growth conditions. Interestingly, Fur and Sae show both complementary and differential regulation as both Fur and Sae positively regulate eap and emp expression in low iron, whereas Fur negatively and Sae positively regulates isdA and isdB transcription. Furthermore, our microarray studies indicate that Fur may also be required for the induced expression of the Agr and Rot regulators in low iron as well as the expression of a number of extracellular virulence factors such as the haemolysins which are also Sae-, Agr-, and Rot-regulated. Hence, Fur is fundamental to S. aureus virulence gene expression.

The Sae regulatory system is essential for biofilm formation (Johnson et al., 2008), the adaptive response to alpha defensins and oxidative stress (Geiger et al., 2008), innate immune evasion and staphylococcal survival in neutrophils (Voyich et al., 2005, 2009). Although sae is expressed in the presence of high concentrations of iron and in iron-rich, complex growth conditions such as TSB, it is at a much lower level than in low-iron, nutrient-poor media reflective of the in vivo environment. This result is consistent with our previous studies showing that Eap and Emp expression levels are significantly higher when S. aureus Newman is grown in low-iron medium, compared to their expression in iron-replete, nutrient-rich media such as TSB (Johnson et al., 2008). Surprisingly, there is differential regulation of the sae transcripts C and D even though D is processed from transcript C and therefore you would expect to see the same level of regulation. However, it is possible that after processing the stability of transcript C is reduced compared to transcript D resulting in a lower observed level of transcript C. This is the first time that sae transcription has been shown to be induced in low-iron conditions and to require Fur for this induced expression. Fur regulation of sae seems to have a major effect on global gene expression as Fur not only induces expression of eap and emp, but, as our proteomics and microarray studies show, Fur and Sae are cooperatively involved in the induction of many exoproteins including the haemolysins, nuclease, lipase, and the IgG-binding protein SBI.

The importance of both sae and fur in virulence has been established previously (Goerke et al., 2001; Horsburgh et al., 2001; Nygaard et al., 2010; Voyich et al., 2009; Xiong et al., 2000), but the link between these 2 regulators had not been established until now. Previous transcriptional profiling of S. aureus grown in vitro in low iron (Allard et al., 2006) and proteomics analysis of cytoplasmic proteins (Freidman et al., 2006) indicated that iron and Fur have a global effect on S. aureus gene expression, although an effect on Sae was not observed. However, the role of Fur in the transcriptional activation of many of the exoprotein virulence determinants or essential global virulence gene regulators in low iron had not been shown previously in S. aureus, or to our knowledge any other bacteria. This study is the first to show that the S. aureus Fur is not just involved in the transcriptional regulation of iron acquisition and storage but is actually essential for the transcription of many virulence genes in low-iron growth conditions possibly mediated through the regulation of important global regulators.

Our previous studies had only shown Fur-mediated low-iron induction of gene expression in S. aureus Newman. However, this study shows the same regulation occurring in a different S. aureus strain, SH1000, as eap, emp, and sae are all positively regulated by Fur in low iron in Newman and SH1000, hence Fur positive regulation in low iron appears to be a general staphylococcal regulatory. However, how Fur activates transcription in low iron is not yet known. Fur could be directly affecting sae expression which in turn would affect the expression of the exoproteins such as eap and emp. However, this does not explain the Fur-mediated regulation of sae itself. It is possible that S. aureus Fur activates transcription through direct binding of target promoters as in Neisseria meningitidis (Delany et al., 2004), although there are no obvious Fur box consensus sequences in any of the positively Fur-regulated promoters. Alternatively, Fur could act indirectly by repressing the expression of another protein regulator or could be involved in post-transcriptional regulation possibly mediated by small, non-coding regulatory RNAs (Majdalani et al., 2005). Regulatory small RNAs have been identified in S. aureus but their roles in gene expression have yet to be fully elucidated (Pichon and Felden, 2005). Fur normally binds DNA when complexed with iron, but we show here that the S. aureus Fur induces expression in low iron. Therefore, there is a possibility that the S. aureus iron-free form of Fur can bind DNA and either repress or activate transcription of downstream regulators as seen in Helicobacter pylori (Bereswill et al., 2000).

The transcriptional profiling suggests that S. aureus Fur positively regulates the agr and rot transcriptional regulators as well as many Agr- and Rot-regulated exoprotein genes. In addition, transcriptional analysis shows that Agr appears to positively regulate sae transcription and negatively regulate fur transcription in low iron. This means that there is a complex feedback loop and that the transcription of all 3 major regulators is closely linked, with Fur playing a central role, although how this regulation occurs is not yet clear (Fig. 4). Previous studies have indicated that in S. aureus Newman sae expression is not regulated by Agr due to an amino acid substitution in the sensor histidine kinase SaeS which results in sae hyperactivation (Adhikari and Novick, 2008; Geiger et al., 2008). However, we show here that sae is clearly regulated by Agr, Fur, and iron in S. aureus Newman despite the amino acid substitution in SaeS. This could be due to the different growth medium used in this study and the possible overriding effects of iron. Alternatively our results suggest that Agr, Fur, and iron-mediated regulation of sae is not via SaeS auto-activation, but is mediated by another mechanism possibly acting directly via the sae operon promoter sequences.

This study indicates that iron concentrations and Fur play an important role in global virulence gene regulation. The low iron concentrations found in vivo can be used as a signal to up-regulate expression of virulence genes. Therefore, it is not surprising that the expression of virulence gene regulators such as Sae is also induced in response to low iron. Sae has been shown to be important for bloodstream infections and staphylococcal survival after neutrophil phagocytosis (Voyich et al., 2005, 2009). Therefore, the low iron concentrations encountered in these environments could be involved in the up-regulation of sae and the Sae-regulated genes required for S. aureus survival in neutrophils. Positive regulation of sae by Fur suggests that Fur is also required for innate immune evasion and intracellular survival in S. aureus. This hypothesis is also supported by the fact that this study shows that both Sae and Fur are required for maximal induction of the oxidative stress response which will be required for intracellular survival in neutrophils. It is interesting that the sae mutant is more resistant to oxidative stress than the wild type, and yet the sae/fur double is clearly even more sensitive than the single fur mutant. It is not clear why this is the case as the actual role of Sae in oxidative stress resistance has not yet been determined. Expression of fur is de-repressed in the sae mutant and therefore the oxidative stress response may be up-regulated via Fur in the sae mutant. Nevertheless both regulators are clearly required for the full response to occur. Our results suggest that Sae, and therefore possibly Fur, may also be essential for staphylococcal survival in the blood and neutrophils as it is required for the induced expression of isdA and isdB in low iron. A substantial level of IsdA and IsdB polypeptide was still observed in the sae mutant extracts although noticeably lower levels of transcripts were detected. This indicates that transcription occurred allowing some translation, but the mRNA was quickly degraded, suggesting that Sae may be involved in post-transcriptional regulation of isdA and isdB expression. IsdA and IsdB have been shown to be important for iron uptake from haem and haemoglobin (Mazamanian et al., 2003) as well as for survival in neutrophils (Voyich et al., 2005). Positive regulation of these important virulence determinants by Sae has not been shown previously, and therefore this data adds another dimension to the role of Sae in pathogenesis. Furthermore, the Sae- and Fur-regulated proteins IsdA, IsdB, Eap, and Emp have been shown to be required for abscess formation and persistence following intravenous infection of mice, suggesting that Fur may also play a role in persistence (Cheng et al., 2009). Therefore our results suggest that Fur has a fundamental role in S. aureus virulence as Fur is required for the induced expression in low iron of sae, agr, and a number of secreted proteins all of which are essential for virulence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Malcolm Horsburgh and Simon Foster for providing SH1000 and the 8325-4 fur mutant and Christiane Goerke for Newman sae::Tn917 (AS3). The DNA microarrays were obtained through NIAID PFGRC-TIGR. This work has been supported by a Grant from the NIH to RKJ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adhikari RP, Novick RP. Regulatory organization of the staphylococcal sae locus. Microbiology. 2008;154:949–959. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/012245-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard M, Moisan H, Brouillette E, Gervais A, Jacques M, Lacasse P, Diarra MS, Malouin F. Transcriptional modulation of some Staphylococcus aureus iron-regulated genes during growth in vitro and in a tissue cage model in vivo. Microb. Infect. 2006;8:1679–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer GL. Staphylococcus aureus: A well-armed pathogen. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1998;26:1179–1181. doi: 10.1086/520289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasopoulos AN, Economopoulou M, Orlova VV, Sobke A, Schneider D, Weber H, Augustin HG, Eming SA, Schubert U, Linn T, Nawroth PP, Hussain M, Hammes HP, Herrmann M, Preissner KT, Chavakis T. The extracellular adherence protein (Eap) of Staphylococcus aureus inhibits wound healing by interfering with host defense and repair mechanisms. Blood. 2006;107:2720–2727. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker J, Sitthisak S, Sengupta M, Johnson M, Jayaswal RK, Morrissey JA. Copper stress induces a global stress response and represses sae and agr expression and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;76:150–160. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02268-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bereswill S, Greiner S, Van Vliet AHM, Waidner B, Fassbinder F, Schiltz E, Kusters JG, Kist M. Regulation of ferritin-mediated cytoplasmic iron storage by the ferric uptake regulator homolog (Fur) of Helicobacter pylori. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:5948–5953. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.5948-5953.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalker AF, Lupas A, Ingraham K, So CY, Lunsford RD, Li T, Bryant A, Holmes DJ, Marra A, Pearson SC, Ray J, Burnham MK, Palmer LM, Biswas S, Zalacain M. Genetic characterization of gram-positive homologs of the XerCD site-specific recombinases. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000;2:225–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavakis T, Hussain M, Kanse SM, Peters G, Bretzel RG, Flock JI, Herrmann M, Preissner KT. Staphylococcus aureus extracellular adherence protein serves as anti-inflammatory factor by inhibiting the recruitment of host leukocytes. Nat. Med. 2002;8:687–693. doi: 10.1038/nm728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavakis T, Wiechmann K, Preissner KT, Herrmann M. Staphylococcus aureus interactions with the endothelium: the role of bacterial “secretable expanded repertoire adhesive molecules” (SERAM) in disturbing host defense systems. Thromb. Haemost. 2005;94:278–285. doi: 10.1160/TH05-05-0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AG, Kim HK, Burts ML, Krausz T, Schneewind O, Missiakas DM. The FASEB Journal. 2009;23:3393–3404. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-135467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SR, Mohamed R, Bian L, Routh AF, Kokai-Kun JF, Mond JJ, Tarkowski A, Foster SJ. The Staphylococcus aureus surface protein IsdA mediates resistance to innate defenses of human skin. Cell. Host Microbe. 2007;1:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke SR, Andre G, Walsh EJ, Dufrene YF, Foster TJ, Foster SJ. Iron-regulated surface determinant protein A mediates adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus to human corneocyte envelope proteins. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:2408–2416. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01304-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale SE, Doherty-Kirby A, Lajoie G, Heinrichs DE. Role of siderophore biosynthesis in virulence of Staphylococcus aureus, identification and characterization of genes involved in production of a siderophore. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:29–37. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.29-37.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delany I, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. Fur functions as an activator and as a repressor of putative virulence genes in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;52:1081–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep BA, Otto M. The role of virulence determinants in community-associated MRSA pathogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 2008;16:361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. Staphylococcal coagulase; mode of action and antigenicity. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1952;6:95–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freidman DB, Stauff DL, Pishchany G, Whitwell CW, Torres VJ, Skaar EP. Staphylococcus aureus redirects central metabolism to increase iron availability. PLoS Pathogens. 2006;2:0777–0789. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T, Goerke C, Mainiero M, Kraus D, Wolz C. The virulence regulator Sae of Staphylococcus aureus: promoter activities and response to phagocytosis-related signals. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:3419–3428. doi: 10.1128/JB.01927-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo AT, Cheung AL, Nagel R. The sae locus of Staphylococcus aureus controls exoprotein synthesis at the transcriptional level. Arch. Microbiol. 1997;168:53–58. doi: 10.1007/s002030050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudo AT, Mansilla C, Chan A, Raspanti C, Nagel R. Studies on the expression of regulatory locus sae in Staphylococcus aureus. Curr. Microbiol. 2003;46:246–250. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3853-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goerke C, Fluckiger U, Steinhuber A, Zimmerli W, Wolz C. Impact of the regulatory loci agr, sarA and sae of Staphylococcus aureus on the induction of alpha-toxin during device-related infection resolved by direct quantitative transcript analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;40:1439–1447. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goerke C, Fluckiger U, Steinhuber A, Bisanzio V, Ulrich M, Bischoff M, Patti JM, Wolz C. Role of Staphylococcus aureus global regulators sae and sigmaB in virulence gene expression during device-related infection. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:3415–3421. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3415-3421.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggar A, Hussain M, Lonnies H, Herrmann M, Norrby-Teglund A, Flock JI. Extracellular adherence protein from Staphylococcus aureus enhances internalization into eukaryotic cells. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:2310–2317. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2310-2317.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraghy N, Kormanec J, Wolz C, Homerova D, Goerke C, Ohlsen K, Qazi S, Hill P, Herrmann M. sae is essential for expression of the staphylococcal adhesins Eap and Emp. Microbiology. 2005;151:1789–1800. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsburgh MJ, Ingham E, Foster SJ. In Staphylococcus aureus, Fur is an interactive regulator with PerR, contributes to virulence, and is necessary for oxidative stress resistance through positive regulation of catalase and iron homeostasis. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:468–475. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.468-475.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsburgh MJ, Aish JL, White IJ, Shaw L, Lithgow JK, Foster SJ. σB modulates virulence determinant expression and stress resistance: characterization of a functional rsbU strain derived from Staphylococcus aureus 8325-4. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:5457–5467. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.19.5457-5467.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M, Becker K, von Eiff C, Schrenzel J, Peters G, Herrmann M. Identification and characterization of a novel 38.5-kilodalton cell surface protein of Staphylococcus aureus with extended-spectrum binding activity for extracellular matrix and plasma proteins. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:6778–6786. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.23.6778-6786.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Cockayne A, Williams PH, Morrissey JA. Iron-responsive regulation of biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus involves fur-dependent and fur-independent mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:8211–8215. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.23.8211-8215.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M, Cockayne A, Morrissey JA. Iron-regulated biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus Newman requires ica and the secreted protein Emp. Infect. Immun. 2008;76:1756–1765. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01635-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Takeda S, Livolsi PJ, Paoletti LC. Effects of in vitro and in vivo growth conditions on expression of type 8 capsular polysaccharide by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:1853–1858. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1853-1858.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin CM, Calderwood SB. Role of iron in regulation of virulence genes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1993;6:137–149. doi: 10.1128/cmr.6.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdalani N, Vanderpool CK, Gottesman S. Bacterial small RNA regulators. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2005;40:93–113. doi: 10.1080/10409230590918702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazamanian SK, Skaar EP, Gaspar AH. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;299:906–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1081147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGavin MH, Krajewska-Pietrasik D, Rydén C, Höök M. Identification of a Staphylococcus aureus extracellular matrix-binding protein with broad specificity. Infect. Immun. 1993;61:2479–2485. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2479-2485.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey JA, Cockayne A, Hill PJ, Williams P. Molecular cloning and analysis of a putative siderophore ABC transporter from Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:6281–6288. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6281-6288.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey JA, Cockayne A, Hammacott J, Bishop K, Denman-Johnson A, Hill PJ, Williams P. Conservation, surface exposure, and in vivo expression of the Frp family of iron-regulated cell wall proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:2399–2407. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.5.2399-2407.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey JA, Cockayne A, Brummell K, Williams P. The staphylococcal ferritins are differentially regulated in response to iron and manganese and via PerR and Fur. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:972–979. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.2.972-979.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthaiyan A, Silverman JA, Jayaswal RK, Wilkinson BJ. Transcriptional profiling reveals that daptomycin induces the Staphylococcus aureus cell wall stress stimulon and genes responsive to membrane depolarization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:980–990. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01121-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygaard T, Pallister K, Ruzevich P, Griffith S, Vuong C, Voyich J. SaeR binds a consensus sequence within virulence gene promoters to advance USA300 pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201:241–254. doi: 10.1086/649570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma M, Haggar A, Flock JI. Adherence of Staphylococcus aureus is enhanced by an endogenous secreted protein with broad binding activity. J. Bacteriol. 1999;181:2840–2845. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.9.2840-2845.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichon C, Felden B. Small RNA genes expressed from Staphylococcus aureus genomic and pathogenicity islands with specific expression among pathogenic strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:14249–14254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503838102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speicher KD, Kolbas O, Harper S, Speicher DW. Systematic analysis of peptide recoveries from in-gel digestions for protein identifications in proteome studies. J. Biomol. Tech. 2000;11:74–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend DE, Wilkinson BJ. Proline transport in Staphylococcus aureus: a high-affinity system and a low-affinity system involved in osmoregulation. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:2702–2710. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.8.2702-2710.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyich JM, Braughton KR, Sturdevant DE, Whitney AR, Said-Salim B, Porcella SF, Long RD, Dorward DW, Gardner DJ, Kreiswirth BN, Musser JM, DeLeo FR. Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3907–3919. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyich JM, Vuong C, Dewald M, Nygaard TK, Kocianova S, Griffith S, Jones J, Iverson C, Sturdevant DE, Braughton KR, Whitney AR, Otto M, Deleo FR. The SaeR/S gene regulatory system is essential for innate immune evasion by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;6:269–275. doi: 10.1086/598967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong A, Singh VK, Cabrera G, Jayaswal RK. Molecular characterization of the ferric-uptake regulator, fur, from Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 2000;146:659–668. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-3-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.