Abstract

CXCR1 and CXCR2 are G-protein coupled receptors, that have been shown to play important role in tumor growth and metastasis, and are prime targets for the development of novel therapeutics. Here, we report that targeting CXCR2 and CXCR1 activity using orally active small molecule antagonist (SCH-527123, SCH-479833) inhibits human colon cancer liver metastasis mediated by decreased neovascularization and enhanced malignant cell apoptosis. There were no differences in primary tumor growth. These studies demonstrate the important role of CXCR2/1 in colon cancer metastasis and that inhibition of CXCR2 and CXCR1, small molecule antagonists provides a novel therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: Chemokine, Angiogenesis, Metastasis, Colon Cancer

1. Introduction

Human colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer among men and women in the United States [1]. It is the third leading cause of cancer related deaths in the United States, with an estimated 51,370 deaths due to the disease in 2010. Over the past 10–15 years overall incidence and deaths due to colorectal cancer have been declining due to early diagnosis. However, a majority of cases still have very poor prognosis and current therapeutic strategies are not effective in advanced metastatic disease.

CXCL8 is a member of the chemokine superfamily of small structurally and functionally related inflammatory cytokines that have been shown to play important roles in inflammation, tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis [2–7]. CXCR1 and CXCR2 bind to CXCL8 with high affinity, but CXCR2 also binds to other chemokines [8–10]. Expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 was found in keratinocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and malignant cells including human colon carcinomas [2, 8, 11–15]. These receptors have been implicated in angiogenic responses, tumor growth and metastasis [3, 16–21]. Both CXCR1 and CXCR2 are G-protein coupled receptors and are prime targets for the development of new therapeutic strategies for various diseases [22–25]. Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that expression of CXCR1, CXCR2 and their ligands play important roles in human colon cancer growth and metastasis [14, 26]. Small molecule inhibitors with affinity for CXCR1 such as repertaxin or affinity for CXCR2 such as SB-225002 or SB-332235 have been used against inflammatory diseases [22, 27, 28]. A recent report from our laboratory demonstrates that small molecule antagonists for CXCR2/1 inhibit human melanoma growth by decreasing tumor cell proliferation, survival, invasive potential and angiogenesis. However, the effectiveness of CXCR1 and/or CXCR2 antagonists in human colon cancer growth and metastasis remains unclear.

We determined the efficacy of the CXCR2/1 antagonists, SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 in inhibiting liver metastasis using an in vivo metastatic model of colon carcinoma. We monitored tumor growth and metastasis and found that while neither compound effectively controlled growth of the cells implanted in the spleen, both compounds were effective in decreasing metastasis to the liver by decreasing angiogenesis and increasing apoptosis of tumor cells. These studies confirm the role of CXCR2 and CXCR1 in colon carcinoma and demonstrate the potential for these compounds to be used as a therapy for colon cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells lines and reagents

The highly metastatic human colon cancer cell line, KM12L4, derived from parent KM12C cells (kind gift from Dr. Isaiah J. Fidler from the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston TX) [29] was maintained in culture as an adherent monolayer in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (MediaTech, Herndon, VA). The media was supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS) (MediaTech), L-glutamine (MediaTech), two-fold vitamin solution (MediaTech), and gentamycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 antagonists were obtained from Schering-Plough Research Institute and dissolved in hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) from Acros Chemical (St. Louis, MO). The inhibition constant (Ki) of CXCR1 and CXCR2 for SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 was calculated from the IC50 value using the Cheng-Prusoff equation [30–32]. These receptor antagonists have been shown to be highly active and specific against human and murine CXCR2 (data not shown).

2.2. Human colon carcinoma cell growth and metastasis in nude mice

Female athymic nude mice (6–8 week old) were purchased from the Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions. All procedures performed were in accordance with institutional guidelines and approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. KM12L4 cells (1×106 in 50 μl of HBSS) were injected into the spleen. 24 hrs after injection, mice were gavaged with 0.2 ml of 100 mg/kg body weight (MPK), 50 MPK or 25 MPK of SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 twice a day for three weeks. For 100 MPK, 100mg of SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 was dissolved in 10 ml of 20% HP3CD by sonication. Control mice were gavaged with 0.2 ml vehicle (20% HP3CD) alone. A minimum of 10 animals were used per group and were monitored for toxicity. After three weeks, local splenic tumors and liver metastases were resected and analyzed. Splenic tumors and liver metastases were fixed and processed for immunohistochemistry. Livers were fixed in Bouin’s fixative and the number of metastatic nodules was evaluated using a dissecting stereomicroscope. Splenic primary tumors and liver metastases were lysed for protein and RNA.

2.3. Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

Briefly, 6-μm thick tumor sections were deparaffinized by EZ-Dewax (Biogenex, SanRoman, CA) and blocked for 30 minutes. Tumor sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: anti-human CXCR1 (1:100; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) anti-human CXCR2 (1:100; R&D Systems) or CD31 (1:100; Novacastra, Bannockburn, IL). The slides were rinsed and incubated in biotinylated secondary antibody (1:500). Immunoreactivity was detected using the ABC Elite kit and DAB substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Apoptotic cells in tumor samples were identified by terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Dead End Colorimetric TUNEL System, Promega, Madison WI). The number of apoptotic cells was evaluated by counting the positive (brown-stained) cells.

Intensity of staining for CXCR1 and CXCR2 expression was graded on a scale of 0 – 3+, with 0 representing no detectable staining and 3+ representing the strongest staining. Two independent observers examined each slide using a Nikon E400 microscope. Additionally, the number of apoptotic cells and microvessel density was quantitated microscopically with a 5×5 reticle grid (Klarmann Rulings, Litchfield, NH) and a 40× objective (250 μm total area).

2.4. Detection of human CXCL1 and CXCL8

Protein levels in tumor lysates were determined using enzyme linked-immunosorbant assay (ELISA) matched-pair antibodies according to the manufacturer’s instruction with modification. In brief, flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (Immuno Plate) were coated with 100 μl of primary monoclonal antibody against human CXCL8 (2 μg/ml, Pierce, Rockford, IL) or human CXCL1 (1 μg/ml, R&D Systems) in PBS overnight at 4°C and were then washed three times with PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (washing buffer). Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with blocking buffer (CXCL8: PBS with 4% BSA, 0.01% Thimerosal, pH 7.2–7.4; CXCL1: PBS with 1% BSA, 5% Sucrose and 0.05% Sodium Azide) for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing three times, CXCL8 was determined by adding 50 μl of tumor lysate or recombinant CXCL8 protein (Pierce) at different concentrations. For CXCL1 detection, 100 μl of lysate or recombinant CXCL1 was added to the plates. After 2 hours plates were washed three times and incubated with the respective biotinylated antibody. Immunoreactivity was determined using the avidin-HRP-TMB detection system (Dako Labs, Denmark). The reactions were stopped by addition of H2SO4 and absorbance determined at 450 nm. A curve of the absorbance versus the concentration of standard wells was plotted. By comparing the absorbance of the samples to the standard curve, we determined the concentration of human CXCL1 or human CXCL8 in the unknown samples.

2.5. In vitro cell proliferation

KM12C and KM12L4 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at low density (1000 cells/well). Following overnight adherence, cells were incubated with media alone or medium containing serum (5 %) with SCH-527123 or HP3CD for 72 h. Different concentrations (0.5, 5.0 and 10.0 ug/ml) of the antagonists were used. Cell proliferation was determined by MTT assay [18, 33]. Growth inhibition was calculated as percent (%) = [100−(A / B) × 100], where A and B are the absorbance of treated and untreated cells, respectively.

2.6. Cell migration assay

To investigate the effect of CXCR2/1 antagonists on colon cancer cell migration, cells (1×106 cells/well) in serum free media were plated in the top chamber of noncoated polyethylene terephthalate membranes (six-well insert, 8 μm pore size; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The bottom chamber contained 1.0 ml serum free media with or without SCH-527123 (0.5, 5.0 and 10.0 ug/ml) in the lower chamber and incubated overnight at 37°C. MTT was added and cells were incubated for an additional 2 h. Cells from the top of the transwell chambers were removed using a cotton swab (residual cells). The transwell chambers (migrated cells) and cotton swab containing residual cells were plated in separate well of a 24-well plate containing 400 ul of DMSO. Following 1 h of gentle shaking, 100 ul samples were removed and absorbancy was determined at 570nm using a microtiter plate reader. The percent invasive activity was calculated [14] as: percent migration = [(A / B) − 1 × 100], where A is the number of migrated cells and B is the number of residual cells.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for statistical comparison of multiple groups. P < 0.05 was considered significant. If significance was found in the ANOVA then post-hoc analysis was performed to compare specific groups using Bonferroni’s correction where the significance level was determined by dividing 0.05 by the number of comparisons to be made. Where only two groups were tested, the Student’s t test was used. In vivo analysis was performed using Mann-Whitney U-test of significance. A value of p<0.05 was deemed significant.

3. Results

3.1. SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 were well-tolerated in mice

SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 selectively inhibit CXCR2 and CXCR1. SCH-479833 has higher Ki’s and is slightly more selective for CXCR2 than SCH-527123 [30–32]. These receptor antagonists have been shown to over 1000-fold selective for CXCR2 and CXCR1 as compared to other G-protein coupled receptors and are also highly active against murine CXCR2 (data not shown). To test the efficacy of these compounds in vivo, we used a metastatic colon cancer model. KM12L4 human metastatic colon cancer cells were injected into the spleen parenchyma of nude mice [34]. After tumor cell inoculation, SCH-527123, SCH-479833 or 20% HβPCD were given orally bid for 3 weeks and mice were monitored daily. Prior to necropsy, mice were weighed and the percent difference between control and treated groups was calculated (data not shown). Overall the treatments were well-tolerated. We did not observe any significant difference in body weight or behavior of SCH-527123 or SCH-479833-treated and control mice (data not shown).

3.2. SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 inhibited liver metastases with no effect on primary tumor growth

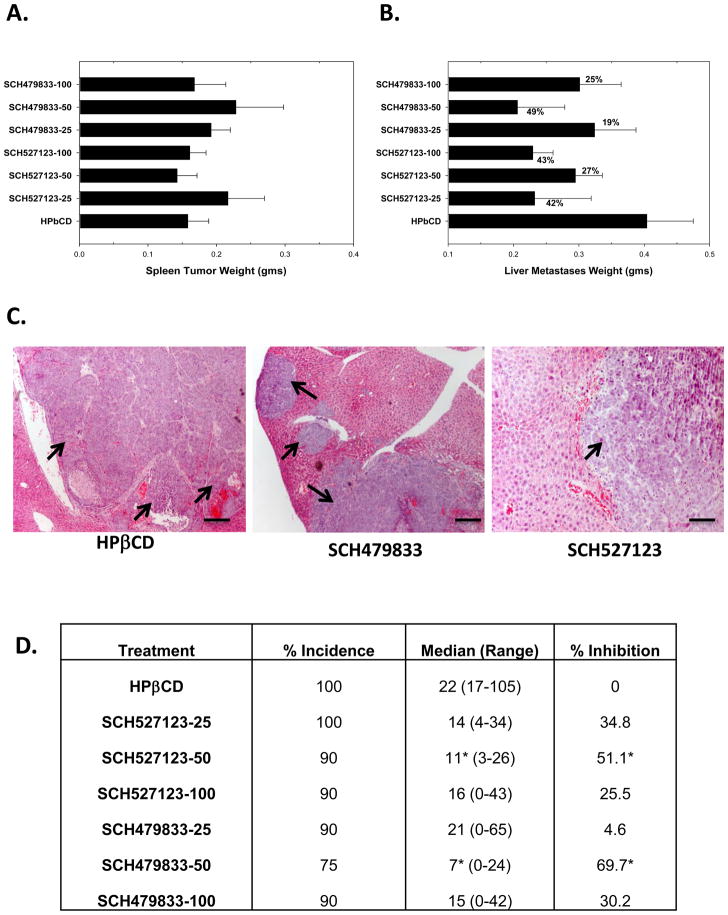

Mice were injected with KM12L4 colon cancer cells in the spleen to produce liver metastases. SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 were given orally at different doses. Mice were necropsied and spleens were resected to evaluate tumor growth. Tumor-bearing spleens were weighed and normalized with spleens from non-tumor bearing mice. There was no detectable difference in spleen size from treated and untreated tumor-bearing mice. We did not observe any significant differences in spleen tumor weight weight among the control and SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 treated groups (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 inhibited colon cancer liver metastases.

A. Primary spleen tumor weights of mice treated with SCH-527123 or SCH-479833. Wet tumor-bearing spleens were weighed and normalized with spleens from normal mice. The values are average normalized weight in grams (gms) ± standard error of mean (SEM). B. Liver metastases in SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 treated animals. The liver metastatic burden was analyzed as described in materials and methods. The values are mean normalized liver metastatic weight ± SEM. C. A representative tumor section showing metastatic nodules in livers of control and antagonist treated mice. Scale bar represents 0.1 mm. D. The incidence of liver metastases. Livers were examined for metastases and the numbers of nodules were counted. The values are the median number of nodules per mouse with the range indicated. The median number of nodules in antagonist treated animals was compared to the control treated group and percent inhibition was calculated. * p<0.05, significantly different from control group.

At necropsy, mice were examined for the presence of distant metastases to the liver. Livers with metastases were removed and weighed (Figure 1B). Gross metastatic burden in the livers was determined following normalization with wet liver weight of non-tumor bearing mice. We observed a decrease in the gross metastatic burden in livers of animals treated with SCH-527123 (27–42% inhibition) or SCH-479833 (19–49% inhibition) as compared to the control group (Figure 1B and C). The incidence of metastases was calculated and the overall incidence of liver metastases decreased following treatment with SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 (Figure 1D). The numbers of metastatic nodules were counted following fixation with Bouin’s solution. Both CXCR2/1 antagonists inhibited the number of metastatic nodules (Figure 1D). We found in the control HβPCD treated group 80% of mice had metastases to other organs, predominantly the lungs and peritoneum, whereas in the antagonist-treated groups the incidence of metastases to other organs varied from 0–30% (data not shown).

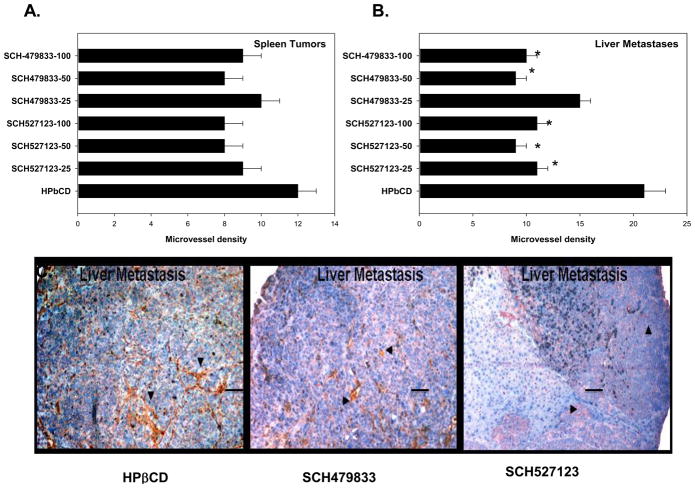

3.3. SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 treatment inhibited neovascularization

The relationship between angiogenesis and metastasis is well-established in colon cancer metastases [35] and CXCR1 and CXCR2 have been shown to play important roles in tumor angiogenesis [20]. Therefore, we examined the extent of neovascularization in primary spleen lesions and metastatic liver nodules with similar size. Tumor sections were immunostained with anti-CD31 antibody and the microvessel density was evaluated (Figure 2C). We observed a decrease (not statistically significant) in the extent of neovascularization in primary lesions (Figure 2A). Moreover, we observed a significantly lower microvessel density in metastatic lesions (Figure 2B and C).

Figure 2. SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 treatment decreased neovascularization in liver metastases.

A. Primary splenic tumors and liver metastatic lesions were immunostained with anti-CD31 antibody and the numbers of microvessels were quantitated. The values are number of microvessel in primary splenic tumors (A) and liver metastases (B). C. A representative liver metastatic nodule showing anti-CD31 staining in control and antagonist SCH527123 (50 MPK) and SCH-479833 (50 MPK) treated mice. * p<0.05, significantly different from control group. Scale bar represents 0.01 mm.

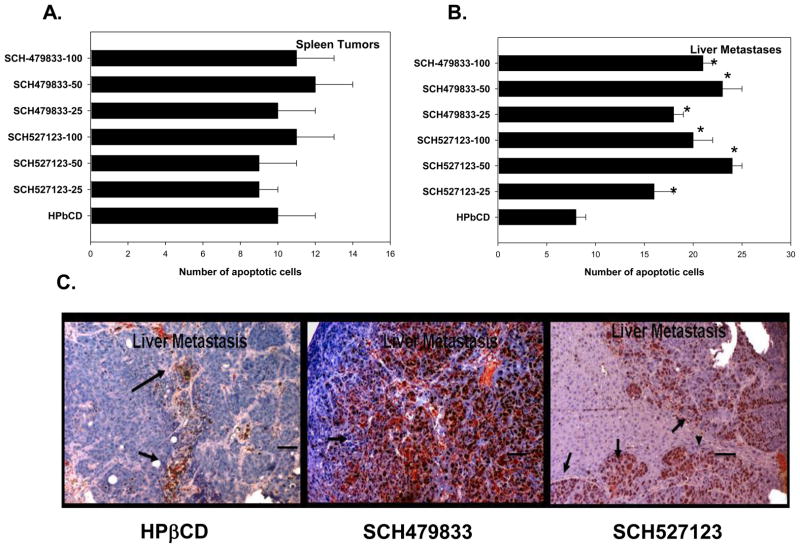

3.4. SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 treatment enhanced apoptosis in liver metastases

Primary spleen lesions as well as metastatic liver lesions were immunostained to detect apoptotic tumor cells (Figure 3C). We did not observe any significant change in the levels of apoptosis in primary splenic tumors (Figure 3A). The levels of apoptotic malignant cells in liver metastases from SCH-57213 or SCH-479833 treated animals were significantly higher as compared to the control group (Figure 3C). We did not observe any difference in the number of apoptotic cells in normal liver tissue among the CXCR2/1 antagonist and control treated groups (data not shown).

Figure 3. CXCR1 and CXCR2 antagonists treatment increased malignant cell apoptosis.

A. Primary tumor and liver metastatic sections were stained for apoptosis using TUNEL and the numbers of apoptotic cells were quantitated. The values are number of apoptotic cells in primary splenic tumors (A) and liver metastases (B). C. A representative liver metastatic section from control and receptor antagonist SCH527123 (50 MPK) and SCH-479833 (50 MPK) treated mice. * p<0.05, significantly different from control group. Scale bar represents 0.01 mm.

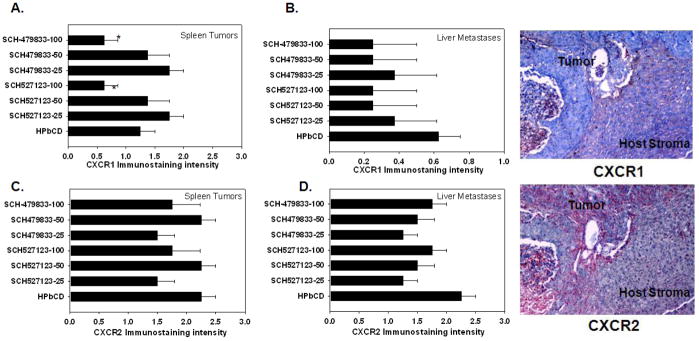

3.5. Human CXCR1 and CXCR2 expression in primary splenic and liver metastatic lesions following SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 treatment

Splenic tumors and liver metastases were immunostained for human CXCR1 and CXCR2 to determine whether treatment of animals with CXCR2/1 antagonists selectively limits growth of CXCR2/1 expressing cells. A significant reduction in the levels of human CXCR1-positive tumor cells was detected in primary tumors from mice treated with 100 MPK of either SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 (Figure 4A). Treatment with either SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 at 25 MPK decreased (not statistically significant) human CXCR2 positive tumor cells in both splenic and liver lesions (Figure 4C and D). There was a general, but not significant, trend toward decreased expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 in malignant cells in liver nodules irrespective of the treatment dose. Immunohistochemocal analysis demonstrated that human CXCL1 and CXCL8 were predominantly expressed in human tumors and their metastases. We did not observe any immunostaining in murine stromal cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Human CXCR1 and CXCR2 expression in splenic lesions and liver metastases.

A. CXCR1 expression in splenic lesions. CXCR1 expression was evaluated by immunostaining in primary splenic lesions (A) and liver metastases (B). CXCR2 expression in primary splenic tumors (C) and liver metastatic lesions (D) were analyzed using IHC. The values are mean immunostaining intensity ± SEM. A representative photomicrograph to demonstrate human CXCR1 and CXCR2 immunostaining in SCH527123-100 MPK treated liver metastases to demonstrate expression of receptors in tumor and host stromal compartment. No immunostaining of human CXCR1 and CXCR2 was observed in murine stromal tissue.

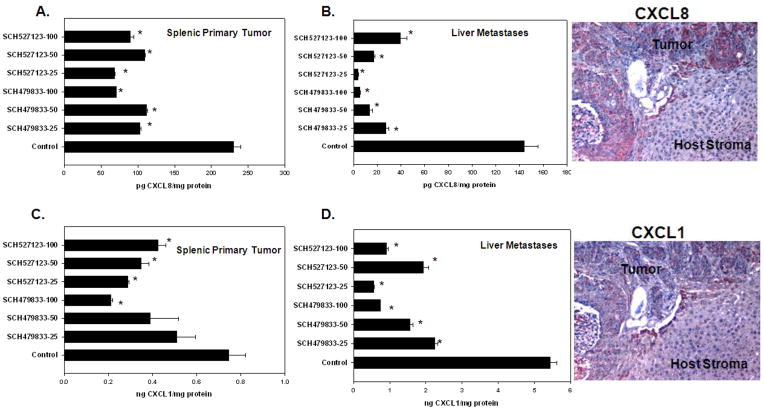

3.6. Modulation of human CXCL1 and human CXCL8 expression in tumors and metastases following SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 treatment

KM12L4 cells express CXCL8 which binds to CXCR1 and CXCR2, as well as CXCL1 which binds to CXCR2 [26]. In the next set of experiments, we determined whether treatment with a CXCR2/1 antagonist modulates expression of the ligand(s). Tumor lysates were measured for expression of CXCL8 and CXCL1. All doses of SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 were effective at decreasing CXCL8 expression in splenic tumors (Figure 5A). The inhibition of CXCL8 was even more dramatic in liver lysates (Figure 5B). Similarly, CXCL1 expression was decreased in spleenic tumors although not as marked as CXCL8 (Figure 5C). Inhibition of CXCL1 expression was also more dramatic in liver metastases (Figure 5D). Immunohistochemocal analysis demonstrated that human CXCL1 and CXCL8 were predominantly expressed in human tumors and their metastases (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Human CXCL8 and CXCL1 expression in splenic and liver lysates.

A. CXCL8 expression in splenic lysates. Treatment with receptor antagonists decreased CXCL8 protein levels in spleens. B. CXCL8 expression in liver lysates. CXCL8 levels in liver lysates were significantly decreased in all antagonist treated groups. C. CXCL1 expression in splenic lysates. CXCL1 expression was slightly decreased in splenic lysates after treatment with CXCR2/1 antagonists. D. CXCL1 expression in liver lysates. Treatment with CXCR2/1 receptor antagonists significantly decreased CXCL1 expression in liver lysates. A representative photomicrograph to demonstrate human CXCL1 and CXCL8 immunostaining in SCH527123-100 MPK treated liver metastases to demonstrate expression of receptors in tumor and host stromal compartment. No immunostaining of human CXCL1 and CXCL2 was observed in murine stromal tissue.

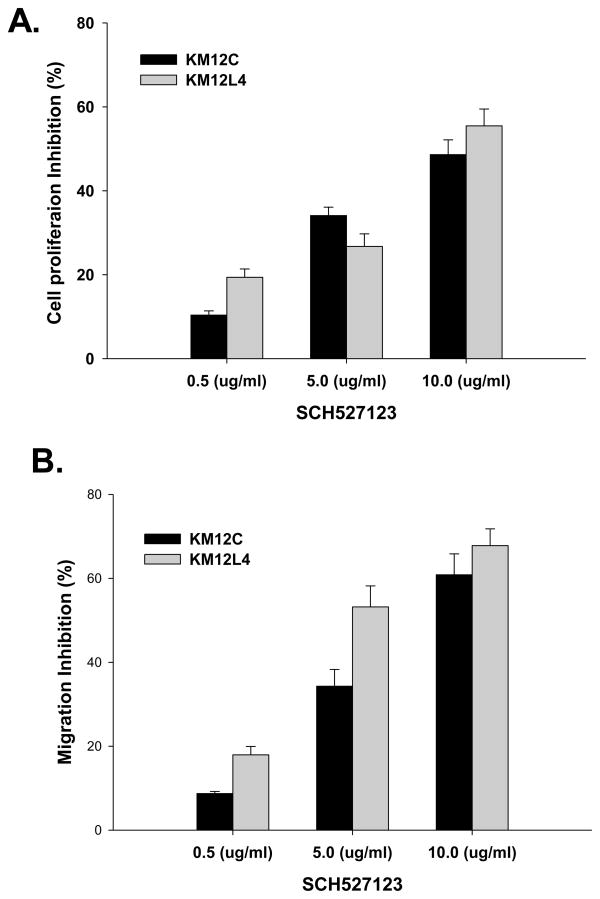

3.7. CXCR2/1 antagonist decreased proliferation and motility of human colon carcinoma cells in vitro

Treatment of human colon carcinoma cells with increasing doses of SCH-527123 (0.5–10.0 ug/ml) resulted in a significant inhibition of cellular proliferation as examined by MTT in vitro proliferation assays (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Inhibition of cell proliferation and motility in CXCR2/1 antagonist treated cells.

A. KM12C and KM12L4 cells (1000 cells/well) in a 96 well plate were cultured in medium with different concentrations of SCH-527123. Cellular proliferation was determined at 72h by MTT assay. The values are mean percent inhibition of proliferation ± SEM. This is a representative of three experiments done in triplicate. B. Cells were plated on non-coated membranes for motility assay, and incubated overnight. Serum free medium containing different concentrations of SCH-527123 was added to the lower chamber. The cells that did not migrate through the Matrigel and/or pores in the membrane were removed, and cells on the other side of the membrane were stained and photographed at 200× magnification. Cells were counted in ten random fields (200×) and expressed as the average number of cells per field of view. The values are number of migrated cells ± SEM.

Next, we investigated whether treatment with CXCR2/1 antagonists would affect tumor cell chemotaxis and invasion. Our data demonstrated a significant (p<0.05) inhibition in motility of SCH-527123 treated cells as compared to control-treated cells (Figure 6B).

4. Discussion

In this study we report that inhibition of signaling by CXCR2 and possibly CXCR1 using orally active small molecule antagonists (SCH-527123 and SCH4-79833) inhibited human colon carcinoma liver metastasis in an experimental mouse model. Furthermore, our study showed that the anti-metastatic activity of these antagonists was due to inhibition of malignant cell survival as well as neovascularization.

The use of small molecule inhibitors represents an attractive targeted therapeutic approach [20, 22, 31]. Previously we have shown the importance of expression of CXCL1 and CXCL8, ligands for CXCR2 and CXCR1, in human colon carcinoma metastasis and angiogenesis [14]. In the present study, we demonstrate that given orally neither SCH-527123 nor SCH-479833 had any effect on primary splenic tumors but both inhibited human colon cancer liver metastasis. This finding clearly indicates the potential of SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 as novel anti-metastatic therapeutics for human colon carcinoma and is in accordance with our previous observations on the association of CXCR2 and CXCR1 with human colon cancer metastasis [2, 14]. Earlier studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that neutralizing antibodies to CXCR1 and CXCR2 inhibit human colon cancer cell proliferation and invasive potential [14]. Small molecule inhibitors with affinity for CXCR1 such as repertaxin or affinity for CXCR2 such as SB-225002 or SB-332235 have been used against inflammatory diseases [22, 27, 28], or prevention of reperfusion injury [22]. A recent report from our laboratory demonstrated that CXCR2 and CXCR1 antagonists inhibit melanoma growth [32].

Although a majority of colorectal carcinomas are resectable, patients subsequently present with metastatic disease. Colorectal cancer commonly metastasizes to the liver and approximately 50% of patients with Stage IV disease develop liver metastases [36]. Therefore adjuvant therapy which aims to eliminate metastatic burden could result in increased survival. Treatment with either compound resulted in an overall decrease in the incidence of liver metastases. The overall growth of the tumor and metastasis in vivo depends on several factors including the rate of tumor cell proliferation, survival, and vascularization of the tumor tissue along with the invasive capacity of the tumor cells [37, 38]. It is interesting to note that we did not observe significant inhibition in primary splenic tumor growth in animals treated with SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 as compared to control. However, we observed significant anti-metastatic activity of these small molecule inhibitors. In order to elucidate the underlying mechanism(s), we analyzed neovascularization, cell survival, human CXCR1 and CXCR2 expression and human CXCL1 and CXCL8 production in primary splenic tumors and liver metastases. It is important to note that there is no murine homologue for human CXCL8, however, a homologue of granulocyte chemotactic protein (GCP)-2 has been identified as one of the most potent murine neutrophil attracting chemokines [39, 40]. We observed significant inhibition of neovascularization and enhanced cellular apoptosis in liver metastases following treatment with SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 as compared to the control group. In contrast, we did not observe any difference in neovascularization or apoptosis in primary splenic tumors among antagonist and control treated groups. Earlier reports have demonstrated that neovascularization and malignant cell survival at metastatic sites are key determinants for establishment of metastasis [41, 42]. The differential response of human colon cancer cells to CXCR1/CXCR2 antagonists in splenic tumor and liver metastasis could be due to differences in the tumor-host cell interaction in specific microenvironment as well as overall drug availability and activity. Our data suggest that CXCR1/2-dependent responses are critical for human colon cancer liver metastasis.

A previous report from our laboratory demonstrated the importance of CXCL8 in mediating binding of colon carcinoma cells to endothelial cells, which might be critical for metastasis [2, 14]. If tumor cells have detached from the primary tumor and are unable to attach to the endothelium it would reason that the cells would undergo apoptosis. TUNEL staining in the tumors showed that treatment with either SCH-527123 or SCH-479833 resulted in an increase in apoptosis in metastatic liver lesions. A decrease in the number of blood vessels would also limit the transport of nutrients within the tumor microenvironment. This reduction should also lend itself to increased apoptosis. The in vitro studies also supported the antiproliferative effect of CXCR2/1 antagonists SCH-479833 and SCH527123, similar to our previous report [32]. Recent reports suggest that expression of CXCR2 ligands and activation of CXCR2-dependent pathways might provide survival signal for malignant tumor cells [43–45]. In addition, CXCR1 and CXCR2 have also been implicated in the haptotactic migration/chemotaxis and angiogenic response of malignant cells [46–48]. Previously, CXCL8 expression by endothelial cells was shown to elicit a chemotactic response for malignant cells through CXCR1 [49]. Our data, in association with published reports, suggest that targeting CXCR2/1 responses using small molecule antagonists will inhibit migration, homing and survival of metastatic colon carcinoma cells.

G-protein coupled receptors are a prime target for the development of new strategies to control various pathologies [22]. SCH527123 has recently been shown to inhibit neutrophil recruitment, mucus production and goblet cell hyperplasia in an animal model of pulmonary inflammation [22]. It is possible that CXCR2/1 antagonists treatment can inhibit leukocyte recruitment to primary tumor and metastatic lesions, which could affect tumor growth angiogenesis and metastasis. Our previous report using CXCR2 knock-out mouse model demonstrates that CXCR2-dependent recruitment of granulocytes modulates melanoma growth and experimental metastasis [32]. These observations together with our data extend the clinical scope of these receptor antagonists in diseases where CXCR1 and CXCR2 are implicated as mediators.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that orally active CXCR2/1 antagonists are highly effective as anti-metastatic therapeutics in human colon cancer liver metastasis. The anti-metastatic activity of these antagonists resulted from decreased tumor vascularity and increased malignant cell apoptosis at the metastatic site. Based on these preclinical findings, SCH-527123 and SCH-479833 represent potential novel anti-metastatic therapeutic agents for human colon cancer liver metastasis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants CA72781 (R.K.S.), and Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA036727) from National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and Nebraska Research Initiative Cancer Glycomics Program (R.K.S.) and Schering-Plough Research Institute.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement

None Declared

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

7. Reference List

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010:2010. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li A, Varney ML, Singh RK. Expression of interleukin 8 and its receptors in human colon carcinoma cells with different metastatic potentials. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3298–3304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruffini PA, Morandi P, Cabioglu N, Altundag K, Cristofanilli M. Manipulating the chemokine-chemokine receptor network to treat cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:2392–2404. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsushima K, Oppenheim JJ. Interleukin 8 and MCAF: novel inflammatory cytokines inducible by IL 1 and TNF. Cytokine. 1989;1:2–13. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(89)91043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi D, Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:217–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waugh DJJ, Wilson C. The Interleukin-8 Pathway in Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6735–6741. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhawan P, Richmond A. Role of CXCL1 in tumorigenesis of melanoma. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsushima K, Oppenheim JJ. Interleukin 8 and MCAF: novel inflammatory cytokines inducible by IL 1 and TNF. Cytokine. 1989;1:2–13. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(89)91043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller MD, Krangel MS. Biology and biochemistry of the chemokines: a family of chemotactic and inflammatory cytokines. Crit Rev Immunol. 1992;12:17–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oppenheim JJ, Zachariae CO, Mukaida N, Matsushima K. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene “intercrine” cytokine family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bar-Eli M. Role of interleukin-8 in tumor growth and metastasis of human melanoma. Pathobiology. 1999;67:12–18. doi: 10.1159/000028045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML, Singh RK. Interleukin-8-induced proliferation, survival, and MMP production in CXCR1 and CXCR2 expressing human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 2002;64:476–481. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2002.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh RK, Varney ML. IL-8 expression in malignant melanoma: implications in growth and metastasis. Histol Histopathol. 2000;15:843–849. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li A, Varney ML, Singh RK. Constitutive expression of growth regulated oncogene (gro) in human colon carcinoma cells with different metastatic potential and its role in regulating their metastatic phenotype. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21:571–579. doi: 10.1007/s10585-004-5458-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaja-Milatovic S, Richmond A. CXC chemokines and their receptors: a case for a significant biological role in cutaneous wound healing. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:1399–1407. doi: 10.14670/hh-23.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schadendorf D, Moller A, Algermissen B, Worm M, Sticherling M, Czarnetzki BM. IL-8 produced by human malignant melanoma cells in vitro is an essential autocrine growth factor. J Immunol. 1993;151:2667–2675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh RK, Gutman M, Radinsky R, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Expression of interleukin 8 correlates with the metastatic potential of human melanoma cells in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3242–3247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh RK, Varney ML. Regulation of interleukin 8 expression in human malignant melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1532–1537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varney ML, Li A, Dave BJ, Bucana CD, Johansson SL, Singh RK. Expression of CXCR1 and CXCR2 receptors in malignant melanoma with different metastatic potential and their role in interleukin-8 (CXCL-8)-mediated modulation of metastatic phenotype. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:723–731. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006814.48627.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh S, Sadanandam A, Singh RK. Chemokines in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:453–467. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9068-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richmond A, Yang J, Su Y. The good and the bad of chemokines/chemokine receptors in melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:175–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-148X.2009.00554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertini R, Allegretti M, Bizzarri C, Moriconi A, Locati M, Zampella G, Cervellera MN, Di C, Cesta VMC, Galliera E, Martinez FO, Di BR, Troiani G, Sabbatini V, D'Anniballe G, Anacardio R, Cutrin JC, Cavalieri B, Mainiero F, Strippoli R, Villa P, Di GM, Martin F, Gentile M, Santoni A, Corda D, Poli G, Mantovani A, Ghezzi P, Colotta F. Noncompetitive allosteric inhibitors of the inflammatory chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2: prevention of reperfusion injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11791–11796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402090101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murphy PM, Baggiolini M, Charo IF, Hebert CA, Horuk R, Matsushima K, Miller LH, Oppenheim JJ, Power CA. International union of pharmacology. XXII. Nomenclature for chemokine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:145–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tjoa BA, Murphy GP. Development of dendritic-cell based prostate cancer vaccine. Immunol Lett. 2000;74:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(00)00254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells TNC, Power CA, Shaw JP, Proudfoot AEI. Chemokine blockers - therapeutics in the making? Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2006;27:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li A, Dubey S, Varney ML, Dave BJ, Singh RK. IL-8 directly enhanced endothelial cell survival, proliferation, and matrix metalloproteinases production and regulated angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2003;170:3369–3376. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White JR, Lee JM, Young PR, Hertzberg RP, Jurewicz AJ, Chaikin MA, Widdowson K, Foley JJ, Martin LD, Griswold DE, Sarau HM. Identification of a potent, selective non-peptide CXCR2 antagonist that inhibits interleukin-8-induced neutrophil migration. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10095–10098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thatcher TH, McHugh NA, Egan RW, Chapman RW, Hey JA, Turner CK, Redonnet MR, Seweryniak KE, Sime PJ, Phipps RP. Role of CXCR2 in cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L322–L328. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00039.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morikawa K, Walker SM, Jessup JM, Fidler IJ. In vivo selection of highly metastatic cells from surgical specimens of different primary human colon carcinomas implanted into nude mice. Cancer Res. 1988;48:1943–1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dwyer MP, Yu Y, Chao J, Aki C, Chao J, Biju P, Girijavallabhan V, Rindgen D, Bond R, Mayer-Ezel R, Jakway J, Hipkin RW, Fossetta J, Gonsiorek W, Bian H, Fan X, Terminelli C, Fine J, Lundell D, Merritt JR, Rokosz LL, Kaiser B, Li G, Wang W, Stauffer T, Ozgur L, Baldwin J, Taveras AG. Discovery of 2-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyl-3-{2-[[ (R)- 1-(5- methylfuran-2-yl)propyl]amino]-3,4-dioxocyclobut-1-enylamino}benzamide (SCH 527123): a potent, orally bioavailable CXCR2/CXCR1 receptor antagonist. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7603–7606. doi: 10.1021/jm0609622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh S, Sadanandam A, Nannuru KC, Varney ML, Mayer-Ezell R, Bond R, Singh RK. Small-Molecule Antagonists for CXCR2 and CXCR1 Inhibit Human Melanoma Growth by Decreasing Tumor Cell Proliferation, Survival, and Angiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2380–2386. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li A, Varney ML, Singh RK. Expression of interleukin 8 and its receptors in human colon carcinoma cells with different metastatic potentials. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:3298–3304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morikawa K, Walker SM, Nakajima M, Pathak S, Jessup JM, Fidler IJ. The influence of organ environment on the growth, selection, and metastasis of human colon cancer cells in nude mice. Cancer Res. 1988;48:6863–6871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellis LM, Hicklin DJ. VEGF-targeted therapy: mechanisms of anti-tumour activity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrc2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellis LM, Takahashi Y, Liu W, Shaheen RM. Vascular endothelial growth factor in human colon cancer: biology and therapeutic implications. Oncologist. 2000;5(Suppl 1):11–15. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-suppl_1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain RK, Safabakhsh N, Sckell A, Chen Y, Jiang P, Benjamin L, Yuan F, Keshet E. Endothelial cell death, angiogenesis, and microvascular function after castration in an androgen-dependent tumor: role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10820–10825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Hayre M, Salanga CL, Handel TM, Allen SJ. Chemokines and cancer: migration, intracellular signalling and intercellular communication in the microenvironment. Biochem J. 2008;409:635–649. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wuyts A, Haelens A, Proost P, Lenaerts JP, Conings R, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J. Identification of mouse granulocyte chemotactic protein-2 from fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Functional comparison with natural KC and macrophage inflammatory protein-2. The Journal of Immunology. 1996;157:1736–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Coillie E, Van Aelst I, Wuyts A, Vercauteren R, Devos R, De Wolf-Peeters C, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Tumor Angiogenesis Induced by Granulocyte Chemotactic Protein-2 as a Countercurrent Principle. American Journal of Pathology. 2001;159:1405–1414. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62527-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fidler IJ, Poste G. The “seed and soil” hypothesis revisited. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:808. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steeg PS. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nat Med. 2006;12:895–904. doi: 10.1038/nm1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Larco JE, Wuertz BRK, Manivel JC, Furcht LT. Progression and Enhancement of Metastatic Potential after Exposure of Tumor Cells to Chemotherapeutic Agents. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2857–2861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Larco JE, Wuertz BRK, Rosner KA, Erickson SA, Gamache DE, Manivel JC, Furcht LT. A Potential Role for Interleukin-8 in the Metastatic Phenotype of Breast Carcinoma Cells. American Journal of Pathology. 2001;158:639–646. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Acosta JC, Gil J. A Role for CXCR2 in Senescence, but What about in Cancer? Cancer Res. 2009;69:2167–2170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Addison CL, Daniel TO, Burdick MD, Liu H, Ehlert JE, Xue YY, Buechi L, Walz A, Richmond A, Strieter RM. The CXC chemokine receptor 2, CXCR2, is the putative receptor for ELR+ CXC chemokine-induced angiogenic activity. J Immunol. 2000;165:5269–5277. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.9.5269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moser B, Loetscher P. Lymphocyte traffic control by chemokines. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:123–128. doi: 10.1038/84219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peiper SC, Wang ZX, Neote K, Martin AW, Showell HJ, Conklyn MJ, Ogborne K, Hadley TJ, Lu ZH, Hesselgesser J, Horuk R. The Duffy antigen/receptor for chemokines (DARC) is expressed in endothelial cells of Duffy negative individuals who lack the erythrocyte receptor. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1311–1317. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramjeesingh R, Leung R, Siu CH. Interleukin-8 secreted by endothelial cells induces chemotaxis of melanoma cells through the chemokine receptor CXCR1. FASEB J. 2003;17:1292–1294. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0560fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]