Abstract

Background

As an E3 ubiquitin ligase and a molecular adaptor, Cbl-b controls the activation threshold of the antigen receptor and negatively regulates CD28 co-stimulation, functioning as an intrinsic mediator of T cell anergy that maintains tolerance. However, the role of Cbl-b in the airway immune response to aeroallergens is unclear.

Objective

To determine the contribution of Cbl-b in tolerance to aeroallergens, we examined ovalbumin (OVA)-induced lung inflammation in Cbl-b deficient mice.

Methods

Cbl-b-/- mice and wildtype (WT) C57BL/6 mice were sensitized and challenged with OVA intranasally, a procedure normally tolerated by WT mice. We analyzed lung histology, BAL total cell counts and differential, cytokines and chemokines in the airway, and cytokine response by lymphocytes after re-stimulation by OVA antigen.

Results

Compared with WT mice, OVA challenged Cbl-b-/- mice showed significantly increased neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltration in the lung and mucus hyperplasia. The serum levels of IgG2a and IgG1, but not IgE, were increased. The levels of inflammatory mediators IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, Eotaxin, and RANTES, but not IL-17A or IL-6, were elevated in the airway of Cbl-b-/- mice. Lymphocytes from Cbl-b-/-mice released increased amount of IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-13, and IP-10 in response to OVA re-stimulation. However, no significant changes were noted in the CD4+CD25+ Treg cell populations in the lung tissues after OVA stimulation and there was no difference between WT and Cbl-b-/- mice.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate that Cbl-b deficiency leads to a breakdown of tolerance to OVA allergen in the murine airways, probably through increased activation of T effector cells, indicating that Cbl-b is a critical factor in maintaining lung homeostasis upon environmental exposure to aeroallergens.

Keywords: Cbl-b, Ubiquitin E3 Ligase, Aeroallergen, Allergic inflammation, Asthma

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways associated with reversible airway obstruction, airway hyperresponsiveness, and airway remodeling [1, 2]. The most common form of asthma is allergic asthma. It is triggered by inhaled allergens, such as house dust mite allergen, pet dander, pollen, and mold, resulting in airway inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, and asthma symptoms. In the immunopathogenesis of allergic asthma, Th2 response to inhaled allergens has been considered critical in the initiation and orchestration of inflammatory responses in the airways [3, 4]. On the other hand, studies in humans have found that the expression of Th1 cytokine IFN-γ is also elevated in the blood and in the airways of severe asthmatic patients [5, 6].

Innocuous aeroallergens are ubiquitous in the environment. However, with similar allergen exposure only some individuals develop clinical allergic symptoms while others do not. In healthy individuals, the immune system develops an allergen-specific tolerance in order to avoid harmful inflammatory responses. Several mechanisms are important in peripheral tolerance, including T cell anergy. T cell activation is a primary step in the initiation of adaptive immune responses against pathogens [7, 8]. The process requires the integration of two distinct signals: the engagement by the T cell receptor (TCR) of an antigenic peptide presented by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) at the plasma membrane of antigen presenting cells (APC), and the interaction of costimulatory signals. In the absence of “danger” signals from pathogens, APCs will present non-pathogenic antigens with little or no costimulation engagement, inducing a long-lasting state of functional unresponsiveness in T cells, namely anergy [9]. In T cells, induction of tolerance is characterized not only by alterations in the levels of protein phosphorylation but also by a general increase in total protein ubiquitination [10]. The expression of E3 ubiquitin ligases GRAIL, Itch and Cbl-b is up-regulated in anergic T cells [10, 11].

Cbl-b is a member of the mammalian Cbl family that consists of c-Cbl, Cbl-b, and Cbl-3 [12, 13]. Cbl-b regulates adaptive immunity by setting activation thresholds for mature lymphocytes [14-16] and is necessary for the induction of T-cell tolerance [11]. Cbl-b binds and promotes ubiquitination of the p85 regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K). This modification affects p85 subcellular localization, reducing its recruitment to the immune synapse and, therefore, preventing the interaction of PI3K with CD28 and the TCR zeta chain [17]. Cbl-b not only desensitizes CD4+ T cell blasts to low number of antigen/MHC complexes at late times after the initiation of priming but also promotes early exit from the cell cycle in the absence of ongoing TCR signaling [18]. The importance of Cbl-b in T cells is underscored by the studies of Cbl-b-deficient mice: Cbl-b-/- T cells show effective activation in the absence of costimulation, which results in spontaneous autoimmunity or enhanced susceptibility to autoantigens [14, 15]. In addition to its essential role in T cell anergy, Cbl-b has also been proposed to regulate B cell anergy [19], T cell response to regulatory T cells [20], mast cell function [21, 22], and macrophage infiltration and activation [23]. However, the functional role of Cbl-b in the regulation of immune tolerance to aeroallergens has not been determined. In this study, we tested the hypothesis that Cbl-b is essential in sustaining immune tolerance to inhaled allergens.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Wildtype C57BL/6 mice were from the Jackson Laboratory. Cbl-b-/- mice on C57BL/6 genetic background were generated as previously described [14]. Mice were used for experiments at 9-11 weeks of age. All mice were housed in cages with microfilters in specific-pathogen free environment in the animal facility at the Johns Hopkins University Asthma and Allergy Center. All procedures performed on mice were in accordance with the NIH guidelines for humane treatment of animals and were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee.

Procedure for inhalational ovalbumin (OVA) allergen sensitization and challenge

Mice were divided into 4 groups: WT-PBS, WT-OVA, Cbl-b-/--PBS, and Cbl-b-/--OVA. The OVA sensitization and challenge protocol is essentially the same as described previously [24], with slight modification. Animals were given intranasally 100 µg of endotoxin-depleted OVA in 50 µl of PBS on day 0, 1, and 2 and a booster on day 7. No adjuvant was added. Starting from day 14, the mice received 3 consecutive daily OVA challenges (20 µg each) intranasally. Control groups received PBS only for both sensitization and challenge. Twenty-four hours after the last challenge, the mice were sacrificed. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples and lung tissues were harvested for the assessment of inflammation and cytokine production. Without LPS, wildtype mice had no or minimum response. This model has been used extensively in our laboratory [24].

Lung tissue and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples

Lung tissue and BAL samples were obtained as previously described [25, 26]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized; the trachea was isolated by blunt dissection; and a small caliber tubing was inserted and secured in the airway. Three volumes of 0.75 ml of PBS with 0.1% BSA were instilled into the lung and gently aspirated and pooled. BAL fluids were centrifuged and supernatants were stored at -70°C until use. The total cell counts and the differential of the cells in the pellet were determined. The lung was perfused with cold PBS through the right ventricle with cut vena cava until the pulmonary vasculature was clean. The whole lung was excised either for RNA and protein analyses or fixed with buffered formalin for histology.

Histology Evaluation

For histologic evaluation, the lungs were inflated with buffered formalin to a fixed pressure and then submerged in fixative overnight. Coronal lung sections were cut at 5-µm thickness and hematoxylin-and-eosin (H&E) and Alcian blue were performed as described [26][27]. Same microscopic magnification was used for the sample slides from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice under comparison.

Cytokines, Chemokines, and Immunoglobulins

The levels of cytokines and chemokines in the BAL and immunoglobulins in the serum were determined using commercial ELISA kits per the manufacturer's instructions (R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN).

Lymphocyte response to stimulation in vitro

Peribronchial lymph nodes were collected from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice 24 hr after last OVA challenge. Single-cell suspension was prepared by mincing the lymph nodes and by passage through a Falcon cell strainer (100 μm mesh size) (BD Bioscience). The cells were pooled for each experimental group. Splenocytes were tested as a comparison for systemic response. For preparation of splenocytes, spleens were removed from mice and single-cell suspension of splenocytes was prepared in a similar manner. Red blood cells were lysed by resuspending the splenocyte suspension in the RBC lysing buffer (0.15 mol/L NH4Cl, 1 mmol/L KHCO3, 0.1 mmol/L Na2 EDTA, pH 7.2–7.4) for 5 minutes and then washing twice in PBS. Cells were cultured at a density of 2×106 cells/ml in complete RPMI medium at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells from immunized mice were re-stimulated with medium only, OVA (100 μg/ml), or α-CD3 mAb (R&D System). After 3 days in culture for peribronchial LN cells and 5 days for splenocytes, cell suspensions were briefly centrifuged at 2000×g to collect the supernatants. Cytokine levels in the supernatant were determined by ELISA.

T regulatory cell (Treg) response

After OVA or PBS challenge, perfused lungs were obtained from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice and cut into fragments. Lung tissues were digested with collagenase-IV (Worthington) (150 U/mL) and DNase I (Roche Applied Science) (10 μL/mL) in RPMI 1640 medium at 37°C for 60 minutes. Single-cell suspension was prepared as described above. The cells were labeled with PE-conjugated CD4 (BD Bioscience) and FITC-conjugated CD25 (eBioscience) and analyzed by flow cytometry. The mean percentages of CD4+CD25+ double positive cells from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice were determined.

Statistics

Results were analyzed using one- or two-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons and unpaired Student t test (two-tailed) for comparison of two sets of data. Data were expressed as mean ± SD. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

When using a commonly used systemic sensitization and airway challenge protocol for acute allergic asthma response with OVA as antigen and aluminum hydroxide as adjuvant via peritoneal injection, immunized Cbl-b-/- mice had the same inflammatory response to OVA in the airway as WT mice (data not shown), indicating that this immunization regimen generates a strong signal that overcomes or bypasses any effect Cbl-b may have. To define the role of Cbl-b in tolerance to allergen in the airway, we adopted a modified local sensitization and challenge protocol without adjuvant or LPS in which WT mice displayed tolerance to OVA challenge whereas Cbl-b-/- mice showed a breakdown of tolerance. Subsequent experiments were all performed using this protocol.

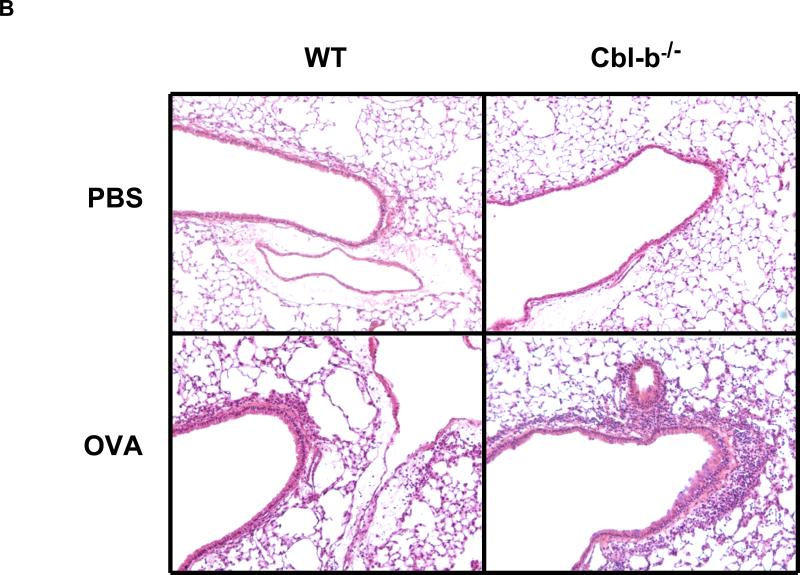

Enhanced inflammatory response in the lung of Cbl-b-/- mice

The results showed that, as controls, PBS treated WT and Cbl-b-/- mice had no inflammation in the airway and lung. WT mice sensitized and challenged with OVA developed minor inflammatory responses, though significantly higher than the PBS control group. Lung histology revealed that WT-OVA mice had a minimal infiltration of inflammatory cells into the lung (Figure 1A and 1B). This observation is consistent with previous reports that mucosal exposure to OVA without LPS induces no or poor inflammatory responses in the lung [24, 28]. This is essentially tolerance to inhaled allergen in WT mice. In contrast, Cbl-b-/-mice sensitized and challenged with OVA showed markedly increased numbers of macrophage, lymphocyte, eosinophil, and neutrophil in the BAL fluids (Figure 1A) and a massive infiltration of inflammatory cells in the lung tissue (Figure 1B). The inflammation in Cbl-b-/- mice was neutrophil-dominant. In addition, Alcian blue staining for mucin-producing cells in the lung sections revealed that WT-PBS and Cbl-b-/--PBS mice had no positive cells, WT-OVA mice had only few, whereas Cbl-b-/--OVA mice had markedly increased goblet cells, particularly in the large airways (Figure 1C). These results demonstrate that in the absence of Cbl-b, normally tolerable aeroallergen induces a robust inflammatory response in the airway.

Figure 1. Inhaled allergen induced inflammatory responses in the lung.

(A) BAL cellularity. Total cell counts and differentials of BAL samples from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice sensitized and challenged with OVA or PBS control. Comparisons were between indicated groups: WT-PBS (n=7), WT-OVA (n=7), Cbl-b-/--PBS (n=8), and Cbl-b-/--OVA (n=11). (B) Lung histopathology. H&E staining of lung sections from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice with OVA sensitization and challenge or PBS control (magnification = 10x). (C) Lung histology. Alcian blue staining for mucin producing cells in the lung of WT and Cbl-b-/- mice received OVA or PBS. A representative slide of each group is shown (magnification = 10x).

Immunoglobulin (Ig) responses

To determine if the levels of allergen specific immunoglobulins in the serum were altered, we collected the serum samples from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice after OVA sensitization and challenge and measured the levels of IgE, IgG1, and IgG2a. The results showed that the serum levels of OVA-specific IgE were very low and there was no difference between WT and Cbl-b-/- groups treated with PBS or OVA. OVA-specific IgG1 in the serum was increased in both WT-OVA mice and Cbl-b-/--OVA mice compared to the PBS groups but there was no difference between the two OVA groups. In contrast, significantly increased levels of OVA-specific IgG2a were only found in Cbl-b-/--OVA mice (Figure 2). These findings demonstrate that Cblb deficiency is related to an increased IgG2a antibody response, which is consistent with the observed Th1-dominated neutrophilic inflammation in the airway.

Figure 2. Antigen-specific immunoglobulin responses.

Serum samples were obtained from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice and levels of OVA-specific IgE, IgG2a, and IgG1 were measured by ELISA. Numbers of mice in each group were WT-PBS (n=7), WT-OVA (n=7), Cbl-b-/--PBS (n=8), and Cbl-b-/--OVA (n=11). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared to PBS group.

Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the BAL fluids

To understand the cytokine basis of the lung inflammation, we analyzed the protein levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the BAL fluids. With PBS treatment, WT and Cbl-b-/- mice had low or undetectable BAL levels of cytokines tested. Upon stimulation with OVA, WT-OVA mice showed a significant increase in IL-12 protein in the BAL. However, Cbl-b-/--OVA mice demonstrated a full-blown response upon OVA stimulation, with markedly upregulated Th1 cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ and chemokine IP-10. On the other hand, Th2 cytokine IL-4 was not upregulated and IL-13 was significantly increased in Cbl-b-/--OVA mice, although the overall levels of these Th2 cytokines were very low. Similarly, IL-10 was significantly induced in Cbl-b-/--OVA mice but the levels were negligible (Figure 3). In all four groups, no IL-17A nor IL-6 could be detected in the BAL samples (data not shown). Compared with WT-PBS mice, WT-OVA mice showed a minimal but significant increase in RANTES, indicating that OVA induced a minimum inflammatory response even in WT mice. In addition, there was a significant increase in total TGF-β1 in WT mice. In contrast, Cbl-b-/--OVA mice failed to develop tolerance and demonstrated robust induction of inflammatory chemokines including MCP-1, MIP-1α, Eotaxin, RANTES, and total TGF-β1 (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Inflammatory cytokines in the airway.

BAL fluid samples were obtained from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice with OVA sensitization and challenge or PBS controls. Cytokine levels were determined by ELISA. Number of mice in each group: WT-PBS (n=7), WT-OVA (n=7), Cbl-b-/--PBS (n=8), and Cbl-b-/--OVA (n=11). Comparisons are between indicated groups and *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Figure 4. Inflammatory chemokines in the airway.

BAL fluid samples were obtained from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice with OVA sensitization and challenge or PBS controls. Chemokine levels were determined by ELISA. Number of mice in each group: WT-PBS (n=7), WT-OVA (n=7), Cbl-b-/--PBS (n=8), and Cbl-b-/--OVA (n=11). Comparisons are between indicated groups and *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Cytokine responses of peribronchial lymph node cells and splenocytes

Spleens and peribronchial lymph nodes of immunized mice were isolated 24 h after the last OVA challenge. Cytokine production was measured in lymph node cell cultures (pooled for each experimental group) and in splenocyte cultures (for each mouse individually) after OVA or TCR simulation. As shown in Figure 5A, 5B, and 5C, with medium treatment there was no cytokine production in cultures of either draining lymph node cells or splenocytes from WT or Cbl-b-/- mice. With OVA antigen re-stimulation, no significant induction of cytokine was seen in the cultures of draining lymph node cells from WT-OVA mice, while remarkable induction was seen in the lymph node cells from Cbl-b-/--OVA mice, including increased Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13, Th1 mediators IFN-γ and IP-10, and IL-10 and TNF-α. These results suggest that differentiated OVA-specific CD4 T cells were significantly increased in the draining lymph nodes of Cbl-b-/- mice and that Th2 cells didn't participate fully in the cytokine production in the lung despite the increased capability of Th2 cells. In the cultures of splenocytes with OVA re-stimulation, the overall results were similar with those of draining lymph node cells, although splenocytes from WT-OVA mice produced all cytokines tested, except for IL-4. When stimulated with α-CD3 mAb, LN cells and splenocytes from both WT-OVA mice and Cbl-b-/--OVA mice produced increased amounts of most cytokines measured, even though Cbl-b-/- cells produced more cytokines than WT cells (Figure 5A, B, and C).

Figure 5. Lymphocyte response to stimulation.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from peribronchial lymph nodes (LN) or spleen from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice after OVA sensitization and challenge or PBS controls. LN cells and splenocytes were stimulated with medium alone, OVA allergen (100 µg/ml), or α-CD3 mAb for designated time period and secreted cytokines in the supernatant were measured by ELISA. (A) Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13. (B) Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and chemokine IP-10. (C) Cytokine IL-10 and TNF-α. Comparisons are between indicated groups.

T regulatory cell response

To determine if changes in Treg cells in the lung tissue were associated with the breakdown of tolerance to aeroallergen in Cbl-b-/- mice, we assessed the CD4+CD25+ cell populations in the lung tissues after OVA stimulation using flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 6, the overall percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells were only about 1% of total cells in the lung. There was no change in WT-OVA mice compared with WT-PBS mice, consistent with a lack of response in these mice. Although there was a modest increase in the numbers of Treg cells in Cbl-b-/--OVA mice, there was no statistical difference between this group and others. These data indicate that Treg cells are probably not involved in the breakdown of tolerance in Cbl-b deficiency.

Figure 6. T regulatory cells in the lung tissue.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from lung tissues from WT and Cbl-b-/- mice received OVA or PBS and CD4+CD25+ Treg cell populations were determined by flow cytometry. The values shown are the mean percentages of CD4+CD25+ cells in the lung. Number of mice in each group: WT-PBS (n=5), WT-OVA (n=8), Cbl-b-/--PBS (n=5), and Cbl-b-/--OVA (n=8). (ns, not significant).

Discussion

Even though aeroallergens are ubiquitous in our living environment, the normal response to allergens in healthy individuals is immune tolerance. Only susceptible individuals develop allergic or asthma responses following exposure to aeroallergens. The immunological mechanisms underlying tolerance to aeroallergens may include activation of T regulatory cells that are able to actively suppress effector T cell functions, development of IgG4 instead of IgE and IgG1, and development of T cell anergy. Based on the evidence from previous studies that E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b is critical in maintaining the threshold for T cell activation and in induction of T cell anergy, we speculated that Cbl-b plays an important role in airway mucosal tolerance to aeroallergen. In the present study we tested this hypothesis using a mouse model of tolerance to inhaled allergen.

Our initial experiments using the commonly used protocol of systemic administration (i.p.) of OVA allergen with adjuvant Alum showed that Cbl-b-/- mice developed a Th2 dominated inflammatory response in the airway that was indistinguishable from that of WT mice (data not shown). This result indicates that Cbl-b has no role in this allergen sensitization process and this systemic Th2-biased protocol is not suitable for testing the function of Cbl-b. However, when tested using an inhalational allergen stimulation protocol, which is similar to allergen exposure in humans, the importance of Cbl-b in tolerance was revealed.

Normally in mice, inhaled allergens in the absence of adjuvant elicit no or very poor inflammatory responses in the airway [24, 28]. In our experiments, after intranasal sensitization and challenge without adjuvant wildtype mice demonstrated only a minimum inflammatory response in the airway and in the lung tissue. In contrast, Cbl-b-/- mice developed a full-blown allergen induced inflammatory response that includes inflammatory cell infiltration in the airway and in the lung tissue, mucus hyperplasia, elevated allergen-specific immunoglobulins, proinflammatory cytokine production, and T cell activation with a mixed feature of Th1/Th2 responses. However, these immunological changes were not paralleled by significant lung physiological changes as the alteration in AHR in Cbl-b-/--OVA mice did not reach statistical significance. This is not completely surprising that as a separate entity, lung physiology may have not changed to the same extent as inflammatory and immune responses. Nonetheless, these results demonstrate that Cbl-b deficiency leads to a breakdown of tolerance to OVA antigen in the airways, suggesting that Cbl-b is critical in maintaining lung homeostasis when exposed to aeroallergens.

To further examine the cellular immune responses we performed antigen recall response experiments using isolated cells from bronchial draining lymph nodes or spleen. Without OVA antigen or TCR stimulation, LN cells and splenocytes from WT or Cbl-b-/- mice did not produce any cytokines. When incubated with OVA antigen, WT cells did not produce Th1 cytokine IFN-γ or Th2 cytokine IL-4. However, Cbl-b-/- cells produced significant amounts of IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-13 (Fig. 5A and 5B). WT cells showed a lack of response to OVA antigen since similar cytokine responses were seen in WT cells and Cbl-b deficient cells when stimulated with anti-CD3.

The expression of Ig subclass is influenced by multiple factors, including the prevailing cytokine environment. For example, Th2 cytokine IL-4 preferentially induces class switching to IgG1 and IgE, whereas TGF-β induces switching to IgG2b and IgA [29-31]. Alternatively, the presence of Th1 cytokines such as IFN-γ results in IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 switching [32]. Cbl-b deficient mice had elevated OVA-specific IgG2a in the serum after antigen stimulation and this change was correlated with increased Th1 cytokines IL-12 and IFN-γ in the lung.

In Cbl-b deficient mice stimulated with OVA, there were elevated levels of IL-4 and IL-13 in the BAL fluid but the overall levels of these Th2 cytokines were low. Even though, there was still low-grade but clear eosinophilic inflammation and marked goblet cell metaplasia in the airways of these mice. On the other hand, the increase in Th1 cytokines in the lung of Cbl-b-/- mice was more prominent, correlating with neutrophilia and increased serum IgG2a. Studies by our group and others have shown that inhaled allergen in the presence of varying levels of LPS can induce a Th17 response with neutrophilia in the lung [33, 34]. However, in this study the levels of IL-17A and IL-6 in the BAL samples of all 4 groups of mice were undetectable, indicating that Th17 was not involved in this setting. Together, these data indicate that the breakdown of tolerance in Cbl-b-/- mice resulted in a Th1/Th2 mixed immune response.

It is of note that when stimulated in vitro, antigen-specific T cell responses in Cbl-b deficient cells were significantly enhanced as reflected by increased production of both Th1 and Th2 cytokines. This pattern is different from the Th1-dominated inflammatory response and immunoglobulin response in vivo in Cbl-b-/- mice. Further study is necessary to understand this discrepancy between the inflammatory phenotype in the lung tissue and the capacity of antigen-specific T cells to produce cytokines.

From previous studies on the function of Cbl-b there are several possible mechanisms that may underlie the breakdown of immune tolerance to aeroallergen in Cbl-b-/- mice; 1) Cbl-b deficient T cells failed to develop T cell anergy [11]; 2) Cbl-b deficient T cells are less sensitive to regulatory T cell-mediated suppression [20]; 3) Cbl-b deficient Th1 cells are resistant to activation-induced apoptosis [35]; and 4) Th2 cells could be suppressed by highly upregulated Th1 cytokines. Our experiments showed that Treg cell populations in the lung tissue were not significantly changed in WT and Cbl-b-/- mice after OVA stimulation, suggesting that Treg cells may not be involved in the breakdown of tolerance in the aeroallergen context. This finding is consistent with what has been suggested by Tsitoura et al, in a study in which inhaled OVA induced immune tolerance was mediated by functionally impaired CD4+ T cells without involvement of active suppression [36]. Further studies are needed to investigate whether Cbl-b is involved in T cell differentiation and/or effector T cell recruitment in the context of aeroallergen stimulation.

Peripheral T cell tolerance is an important component of healthy immune responses to inhaled allergens. Cbl-b is a key molecule in the induction of tolerance and in maintaining immunological homeostasis in the airway. Our findings in this study established a direct functional link between Cbl-b and airway immune responses. More studies are necessary for further understanding of the complex mechanisms in immune tolerance to aeroallergens and for the development of novel approaches to maintaining tolerance to aeroallergens.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants to Z. Zhu (R01HL079349-01) and to T. Zheng (R01AI075025-01). D.L.B. is a National Cancer Institute of Canada Research Scientist supported by National Cancer Institute of Canada and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. S.H.C. was supported by a fellowship grant provided by Hanyang University College of Medicine, Korea.

Abbreviations

- Cbl-b

Casitas B Lymphoma b

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

References

- 1.Cutz E, Levison H, Cooper DM. Ultrastructure of airways in children with asthma. Histopathology. 1978;2:407–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1978.tb01735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bochner BS, Undem BJ, Lichtenstein LM. Immunological aspects of allergic asthma. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:295–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.001455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, Schofield B, Neben TY, Karp CL, Donaldson DD. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282:2258–61. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grunig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, Venkayya R, Brombacher F, Rennick DM, Sheppard D, Mohrs M, Donaldson DD, Locksley RM, Corry DB. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998;282:2261–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Magnan AO, Mely LG, Camilla CA, Badier MM, Montero-Julian FA, Guillot CM, Casano BB, Prato SJ, Fert V, Bongrand P, Vervloet D. Assessment of the Th1/Th2 paradigm in whole blood in atopy and asthma. Increased IFN-gamma-producing CD8(+) T cells in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1790–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9906130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho SH, Stanciu LA, Holgate ST, Johnston SL. Increased interleukin-4, interleukin-5, and interferon-gamma in airway CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in atopic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:224–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1416OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamradt T, Mitchison NA. Tolerance and autoimmunity. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:655–64. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103013440907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker LS, Abbas AK. The enemy within: keeping self-reactive T cells at bay in the periphery. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:11–9. doi: 10.1038/nri701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz RH. T cell anergy. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:305–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heissmeyer V, Macian F, Im SH, Varma R, Feske S, Venuprasad K, Gu H, Liu YC, Dustin ML, Rao A. Calcineurin imposes T cell unresponsiveness through targeted proteolysis of signaling proteins. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:255–65. doi: 10.1038/ni1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeon MS, Atfield A, Venuprasad K, Krawczyk C, Sarao R, Elly C, Yang C, Arya S, Bachmaier K, Su L, Bouchard D, Jones R, Gronski M, Ohashi P, Wada T, Bloom D, Fathman CG, Liu YC, Penninger JM. Essential role of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b in T cell anergy induction. Immunity. 2004;21:167–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keane MM, Rivero-Lezcano OM, Mitchell JA, Robbins KC, Lipkowitz S. Cloning and characterization of cbl-b: a SH3 binding protein with homology to the c-cbl proto-oncogene. Oncogene. 1995;10:2367–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thien CB, Langdon WY. Cbl: many adaptations to regulate protein tyrosine kinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:294–307. doi: 10.1038/35067100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiang YJ, Kole HK, Brown K, Naramura M, Fukuhara S, Hu RJ, Jang IK, Gutkind JS, Shevach E, Gu H. Cbl-b regulates the CD28 dependence of T-cell activation. Nature. 2000;403:216–20. doi: 10.1038/35003235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bachmaier K, Krawczyk C, Kozieradzki I, Kong YY, Sasaki T, Oliveira-dos-Santos A, Mariathasan S, Bouchard D, Wakeham A, Itie A, Le J, Ohashi PS, Sarosi I, Nishina H, Lipkowitz S, Penninger JM. Negative regulation of lymphocyte activation and autoimmunity by the molecular adaptor Cbl-b. Nature. 2000;403:211–6. doi: 10.1038/35003228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krawczyk C, Bachmaier K, Sasaki T, Jones RG, Snapper SB, Bouchard D, Kozieradzki I, Ohashi PS, Alt FW, Penninger JM. Cbl-b is a negative regulator of receptor clustering and raft aggregation in T cells. Immunity. 2000;13:463–73. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang D, Liu YC. Proteolysis-independent regulation of PI3K by Cbl-b-mediated ubiquitination in T cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:870–5. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Zhang N, Mueller DL. Casitas B-lineage lymphoma b inhibits antigen recognition and slows cell cycle progression at late times during CD4+ T cell clonal expansion. J Immunol. 2008;181:5331–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitaura Y, Jang IK, Wang Y, Han YC, Inazu T, Cadera EJ, Schlissel M, Hardy RR, Gu H. Control of the B cell-intrinsic tolerance programs by ubiquitin ligases Cbl and Cbl-b. Immunity. 2007;26:567–78. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wohlfert EA, Callahan MK, Clark RB. Resistance to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and TGF-beta in Cbl-b-/- mice. J Immunol. 2004;173:1059–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gustin SE, Thien CB, Langdon WY. Cbl-b is a negative regulator of inflammatory cytokines produced by IgE-activated mast cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:5980–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Chiang YJ, Hodes RJ, Siraganian RP. Inactivation of c-Cbl or Cbl-b differentially affects signaling from the high affinity IgE receptor. J Immunol. 2004;173:1811–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirasaka K, Kohno S, Goto J, Furochi H, Mawatari K, Harada N, Hosaka T, Nakaya Y, Ishidoh K, Obata T, Ebina Y, Gu H, Takeda S, Kishi K, Nikawa T. Deficiency of Cbl-b gene enhances infiltration and activation of macrophages in adipose tissue and causes peripheral insulin resistance in mice. Diabetes. 2007;56:2511–22. doi: 10.2337/db06-1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YK, Oh SY, Jeon SG, Park HW, Lee SY, Chun EY, Bang B, Lee HS, Oh MH, Kim YS, Kim JH, Gho YS, Cho SH, Min KU, Kim YY, Zhu Z. Airway exposure levels of lipopolysaccharide determine type 1 versus type 2 experimental asthma. J Immunol. 2007;178:5375–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu Z, Homer RJ, Wang Z, Chen Q, Geba GP, Wang J, Zhang Y, Elias JA. Pulmonary expression of interleukin-13 causes inflammation, mucus hypersecretion, subepithelial fibrosis, physiologic abnormalities, and eotaxin production. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:779–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI5909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng T, Zhu Z, Wang Z, Homer RJ, Ma B, Riese RJ, Jr., Chapman HA, Jr., Shapiro SD, Elias JA. Inducible targeting of IL-13 to the adult lung causes matrix metalloproteinase- and cathepsin-dependent emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1081–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI10458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh SY, Zheng T, Kim YK, Cohn L, Homer RJ, McKenzie AN, Zhu Z. A critical role of SHP-1 in regulation of type 2 inflammation in the lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40:568–74. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0225OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eisenbarth SC, Piggott DA, Huleatt JW, Visintin I, Herrick CA, Bottomly K. Lipopolysaccharide-enhanced, toll-like receptor 4-dependent T helper cell type 2 responses to inhaled antigen. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1645–51. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finkelman FD, Goroff DK, Fultz M, Morris SC, Holmes JM, Mond JJ. Polyclonal activation of the murine immune system by an antibody to IgD. X. Evidence that the precursors of IgG1-secreting cells are newly generated membrane IgD+B cells rather than the B cells that are initially activated by anti-IgD antibody. J Immunol. 1990;145:3562–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stavnezer J. Regulation of antibody production and class switching by TGF-beta. J Immunol. 1995;155:1647–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snapper CM, Waegell W, Beernink H, Dasch JR. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 is required for secretion of IgG of all subclasses by LPS-activated murine B cells in vitro. J Immunol. 1993;151:4625–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–73. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim YS, Hong SW, Choi JP, Shin TS, Moon HG, Choi EJ, Jeon SG, Oh SY, Gho YS, Zhu Z, Kim YK. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a key mediator in the development of T cell priming and its polarization to type 1 and type 17 T helper cells in the airways. J Immunol. 2009;183:5113–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson RH, Whitehead GS, Nakano H, Free ME, Kolls JK, Cook DN. Allergic sensitization through the airway primes Th17-dependent neutrophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:720–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0573OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanlon A, Jang S, Salgame P. Cbl-b differentially regulates activation-induced apoptosis in T helper 1 and T helper 2 cells. Immunology. 2005;116:507–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsitoura DC, DeKruyff RH, Lamb JR, Umetsu DT. Intranasal exposure to protein antigen induces immunological tolerance mediated by functionally disabled CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1999;163:2592–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]