Abstract

Background and aims

In type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) chronic beta-cell stimulation and oligomers of aggregating human islet amyloid polypeptide (h-IAPP) cause beta-cell dysfunction and induce beta-cell apoptosis. Therefore we asked whether beta-cell rest prevents h-IAPP induced beta-cell apoptosis.

Materials and methods

We induced beta-cell rest with a beta-cell selective KATP-channel opener (KATPCO) in RIN-cells and human islets exposed to h-IAPP versus r-IAPP. Apoptosis was quantified by time-lapse video microscopy (TLVM) in RIN-cells and TUNEL staining in human islets. Whole islets were also studied with TLVM over 48h to examine islet architecture.

Results

In RIN-cells and human islets h-IAPP induced apoptosis (p<0.001 h-IAPP versus r-IAPP). Concomitant incubation with KATPCO inhibited apoptosis (p<0.001). KATPCO also reduced h-IAPP induced expansion of whole islets (disintegration of islet architecture) by ~70% (p<0.05). Thioflavin-binding assays show that KATPCO does not directly inhibit amyloid formation.

Conclusions

Opening of KATP-channels reduces beta-cell vulnerability to apoptosis induced by h-IAPP oligomers. This effect is not due to a direct interaction of KATPCO with h-IAPP, but might be mediated through hyperpolarization of the beta-cell membrane induced by opening of KATP-channels. Induction of beta-cell rest with beta-cell selective KATP-channel openers may provide a strategy to protect beta-cells from h-IAPP induced apoptosis and to prevent beta-cell deficiency in T2DM.

Introduction

Chronic stimulation of beta-cells imposed by insulin resistance is a risk factor for the development of beta-cell dysfunction and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) since it causes depletion of islet insulin stores and beta-cell loss [1–3]. Chronic elevations of glycemia are considered to be a central mechanism for this effect since in subjects with T2DM protection of beta-cells from the stimulatory effect of glucose by overnight inhibition of insulin secretion (induction of beta-cell rest) causes quantitative normalization of insulin secretion upon subsequent stimulation [4]. Similarly, depletion of islet insulin stores and impairments of biphasic and pulsatile insulin secretion induced by prolonged exposure of human islets to elevated glucose concentrations can be prevented by intermittent induction of beta-cell rest using a beta-cell selective KATP-channel opener (KATPCO) [2]. Besides these effects on beta-cell function chronic hyperglycemia also influences beta-cell survival by creating a proapoptotic cellular environment [5–7]. This is partially due to chronically increased shuttling of client proteins through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). In consequence ER-associated stress pathways and proapoptotic genes are upregulated leading to an increased vulnerability of the beta-cell to additional toxic factors [8]. One of these factors may be islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP). In T2DM the islet is characterized by islet amyloid deposits derived from IAPP and a ~65% deficit in beta-cell mass [9–11]. IAPP is a beta-cell hormone and in humans but not in rodents it has the propensity to aggregate into fibrils and form islet amyloid deposits [9; 11–15]. Oligomers or intermediates of this aggregation process have been shown to be cytotoxic and induce beta-cell apoptosis [13–18]. Moreover IAPP oligomers damage cell-to-cell adherence in human islets leading to disruption of islet architecture and a decrease in coordinate islet function (increased entropy of insulin secretion and diminished coordinate insulin secretory pulses) [17]. Thus human IAPP (h-IAPP) induced islet damages contribute to islet dysfunction and beta-cell deficiency in T2DM. Since induction of beta-cell rest by opening of beta-cell KATP-channels provided protection from chronic beta-cell stimulation and glucotoxicity and improved beta-cell survival [2; 19; 20] we hypothesize that beta-cell rest reduces the vulnerability of beta-cells and human islets towards h-IAPP induced toxicity. More specifically we were asking the question whether the induction of beta-cell rest using a beta-cell selective KATP-channel opener prevents h-IAPP induced beta-cell apoptosis and disruption of human islet architecture.

Materials and Methods

Human pancreatic islets were isolated from the pancreas retrieved from a total of five non-diabetic, heart-beating organ donors by the Diabetes Institute for Immunology and Transplantation, University of Minnesota (Bernhard J. Hering) and the Northwest Tissue Center Seattle (R. Paul Robertson). The islets were maintained in RPMI culture medium at 5 mM glucose and 37°C in humidified air containing 5 % CO2. After the islet isolation process the islets were cultured for three to five days before experiments were performed.

Data in control and IAPP groups from static incubation of human islets, TLVM of RIN-cells and human islets and thioflavin T assays have partially been published before [14; 17; 21].

Static incubation

For static incubation experiments aliquots of human islets were incubated for 48 hours with vehicle (H2O + 0.5% acetic acid), 40 µM r-IAPP, 40 µM h-IAPP and 40 µM h-IAPP + 3 µM KATPCO (NN414; 6-chloro-3-(1-methylcyclopropyl)amino-4H-thieno[3,2-e]-1,2,4-thiadiazine 1,1-dioxide [2]). After static incubation the number of apoptotic cells in human islets was detected using the TUNEL staining method (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, AP; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Tissue samples were analyzed on an inverted microscope (Inverted System Microscope IX 70; Olympus, Melville, NY) as described previously [17].

Time-lapse video microscopy (TLVM)

TLVM is a technique that allows real-time imaging of living tissue. RIN cells (a gift from C. J. Rhodes), a rodent beta-cell line, were maintained in culture in Click’s culture medium with 10 mmol/l glucose and 10% FBS at 37°C in humidified air containing 5% CO2. After trypsin digestion of the primary cell culture, aliquots of suspended cells were placed in a specially prepared microculture dish (2.3-cm diameter, ΔT Culture Dish; Bioptechs, Butler, PA) and kept in a conventional incubator (Model 3110; Forma Scientific, Marjetta, OH) over the following 24 h. TLVM was then performed as previously described [14]. Briefly, the microculture dish was removed from the incubator and mounted onto the motorized stage (H107, ProScan; Prior Scientific) of an inverted microscope (Inverted System Microscope IX 70; Olympus, Melville, NY). The temperature inside the dish was dynamically controlled to 37 ± 0.1°C (ΔT Culture Dish Controller, Bioptechs). For time-lapse experiments images of selected fields were acquired with an analogue camera (3-CCD camera; Optornics) every 10 minutes, stored and analyzed on a personal computer.

TLVM of isolated human islets was performed over a 48 hour period as described for RIN cells. Images of islets in static incubation were acquired every 10 minutes. Analysis was performed as previously described [17]. To examine the impact of experimental treatments on islet morphology and integrity we measured the islet cross-sectional area of human islets in 4-hour intervals during the full experimental period. The results are expressed as changes of the islet cross-sectional area in µm2 as a function of time. In prior experiments we established that under these culture conditions measurement of the islet cross-sectional area is a parameter for cell coupling and islet architecture [17].

Thioflavin T fluorescence assay

The fibrillization process of h-IAPP was monitored using the fluorescence increase of thioflavin T (ThT), a dye known to preferentially bind amyloid fibrils. ThT fluorescence increases in a solution of freshly reconstituted peptide as amyloid fibrils grow. For the h-IAPP thioflavin T assay, h-IAPP was reconstituted in 6 M Guanidine-HCl buffer (150 µl per 0.5 mg h-IAPP) and loaded into a hydrated (with deionized water) C-18 silica column (Macro Spin Column, Havard Biosciences, Holliston, MA). Guanidine was washed out with 150 µl deionized water. Then h-IAPP was recovered from the column by application of 150 µl Hexafluoro-2-isopropanol (HFIP). The HFIP in the flow-through was allowed to evaporate and the remaining peptide was reconstituted with deionized water containing 0.5 % acetic acid and 2.5 % HFIP. A 5 µM ThT aliquot in glycine buffer (50 mM) was added to each of the h-IAPP samples (20 µM) and real-time emission intensities were measured at 482 nm with excitation at 450 nm. Measurements were performed at room temperature with excitation and emission slit widths of 1 and 10 nm, respectively. Fluorescence measurements were taken using a Jasco FP-6500 spectrofluorometer. Plots of ThT emission intensity as a function of time were fitted to a sigmoidal curve (non-linear regression analysis).

Calculations and statistical analysis

ANOVA and Tukey's Multiple Comparison Tests were used to test the number of TUNEL positive cells in human islets and human islet cross-sectional areas for statistical significance. Changes in the mean rates of cell death, cell division, and net cell number in time-lapse video microscopy experiments were determined by the Student’s t-test. Changes in the rates of these processes with time were examined by use of ANOVA. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to denote significant differences.

Results

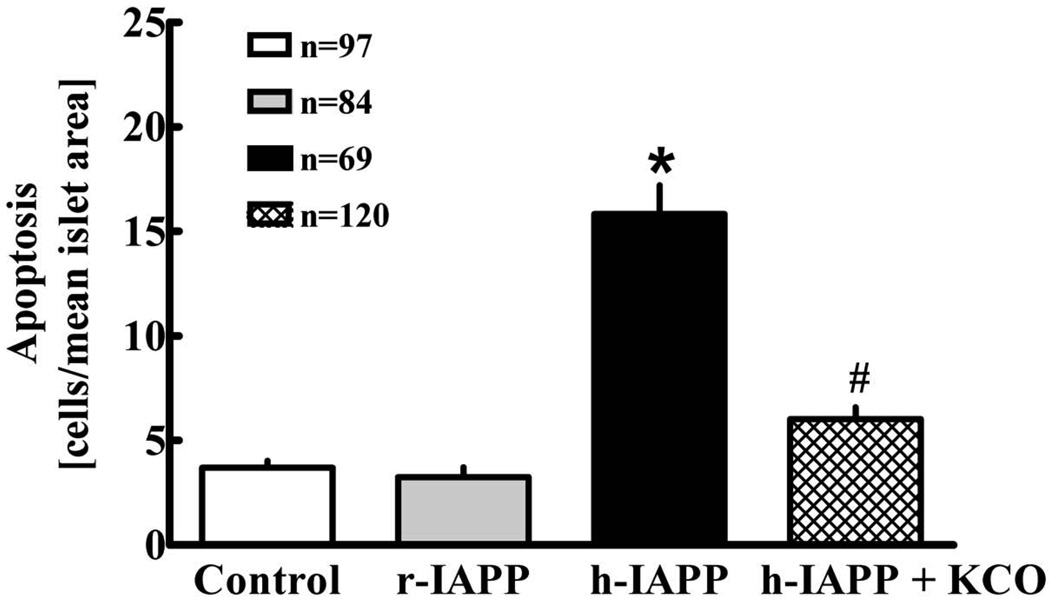

Incubation of isolated human islets with h-IAPP leads to a ~4-fold induction of apoptosis compared to control (p<0.001; Fig. 1). Coincubation with the KATPCO reduces the number of apoptotic islet-cells by ~60% (p<0.001). Non-amyloidogenic r-IAPP does not induce apoptosis.

Fig. 1.

Mean number of apoptotic cells in human islets (n = 5 donors) after incubation for 48 h with vehicle (control), rat IAPP (40 µM), h-IAPP (40 µM) or h-IAPP (40 µM) + KATPCO (3 µM). Numbers indicate islet numbers studied per group. Data ± SEM. P-value derived by ANOVA. Group comparisons by Tukey's Multiple Comparison Tests; *: p < 0.05 versus control. #: p < 0.05 versus h-IAPP.

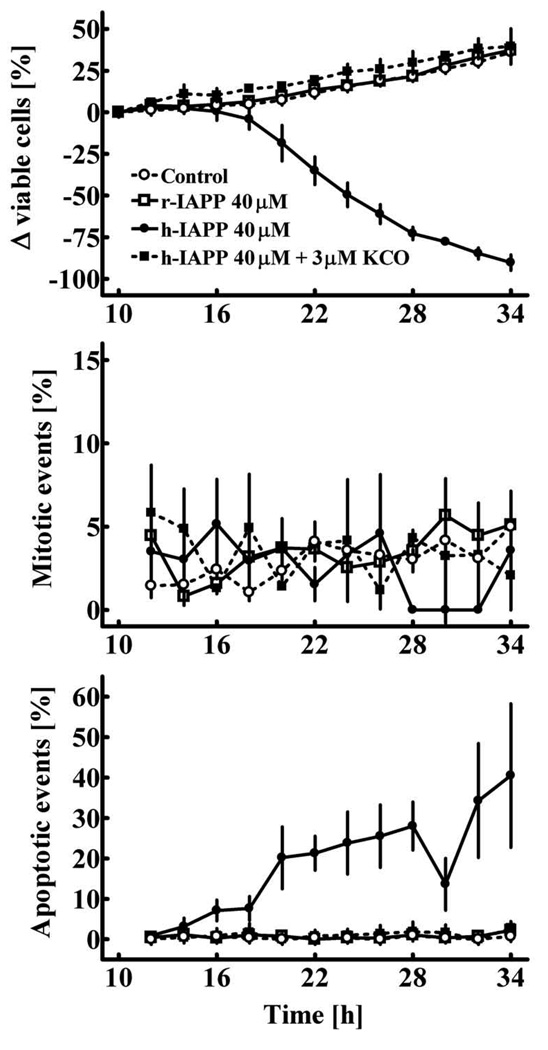

During incubation of RIN cells on the time-lapse microscope there is a continuous expansion of the cell population under control conditions and beta-cells remain morphologically intact (Figs. 2A and 3). In contrast, in experiments with application of h-IAPP after 14–16 hours there is a decline of the cell population caused by an induction of apoptosis (Figs. 2B and 3). Beta-cells undergoing apoptosis show typical morphological changes such as blebbing of the plasma membrane, shrinkage, and fragmentation into apoptotic bodies (Fig. 2B). The mean rate of apoptosis was increased from 0.4 ± 0.1 to 18.8 ± 3.6 % of cells/2h (p<0.001 control versus h-IAPP). Selective activation of beta-cell KATP-channels blocks h-IAPP induced toxicity (1.0 ± 0.2 % of cells/2h; p<0.001 h-IAPP + KATPCO versus h-IAPP) and restores the plasticity of the beta-cell population (Figs 2C and 3). There is no change in the rate of beta-cell replication in these experiments (Fig. 3, middle panel). Non-amyloidogenic r-IAPP does not induce apoptosis in RIN-cells (Figs. 2D and 3).

Fig. 2.

Representative images of RIN cells cultured on the stage of a time-lapse microscope. A: Vehicle (control). B: Rat IAPP. C: Human IAPP. D: Human IAPP + KATPCO.

Fig. 3.

Change in the relative size of the cell population (A), mitotic events (B) and apoptotic events (C) in RIN cells cultured for 24 hours on the stage of a time-lapse video microscope. Vehicle (control), r-IAPP, h-IAPP or h-IAPP and KATPCO were applied to the cells in culture 10 hours before the initiation of time-lapse imaging (p<0.05 indicates significant differences between groups; ANOVA).

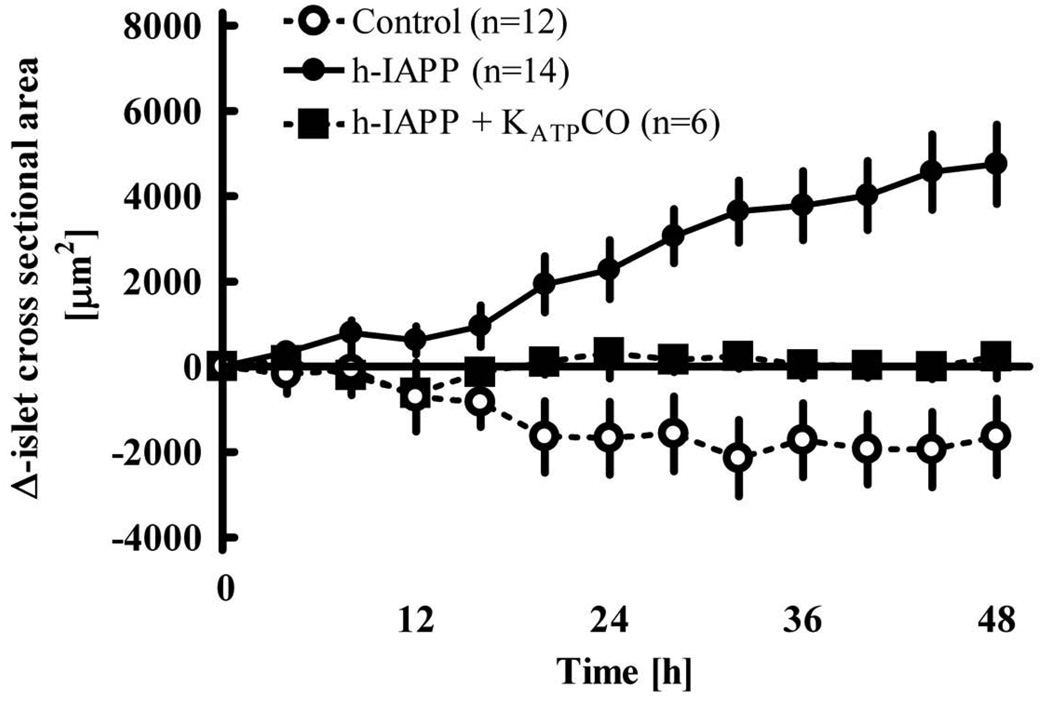

Time-lapse analysis of whole islets reveals that the expansion of the islet cross-sectional area induced by h-IAPP in comparison to control conditions is diminished by ~70% (p<0.001) if the islets are also exposed to KATPCO (Fig. 4). These results imply that beta-cell rest provides partial protection from h-IAPP induced disruption of islet architecture.

Fig. 4.

Change of the islet cross-sectional area during 48h incubation of isolated human islets (n = 3 donors) under control conditions, with h-IAPP 40 µM or h-IAPP 40 µM + KATPCO 3µM. Numbers indicate islet numbers studied per group. P<0.0001 by repeated-measures ANOVA. P<0.05 for control vs h-IAPP, control vs h-IAPP+KCO and h-IAPP vs h-IAPP+KCO (Tukey's Multiple Comparison Test). Data ± SEM.

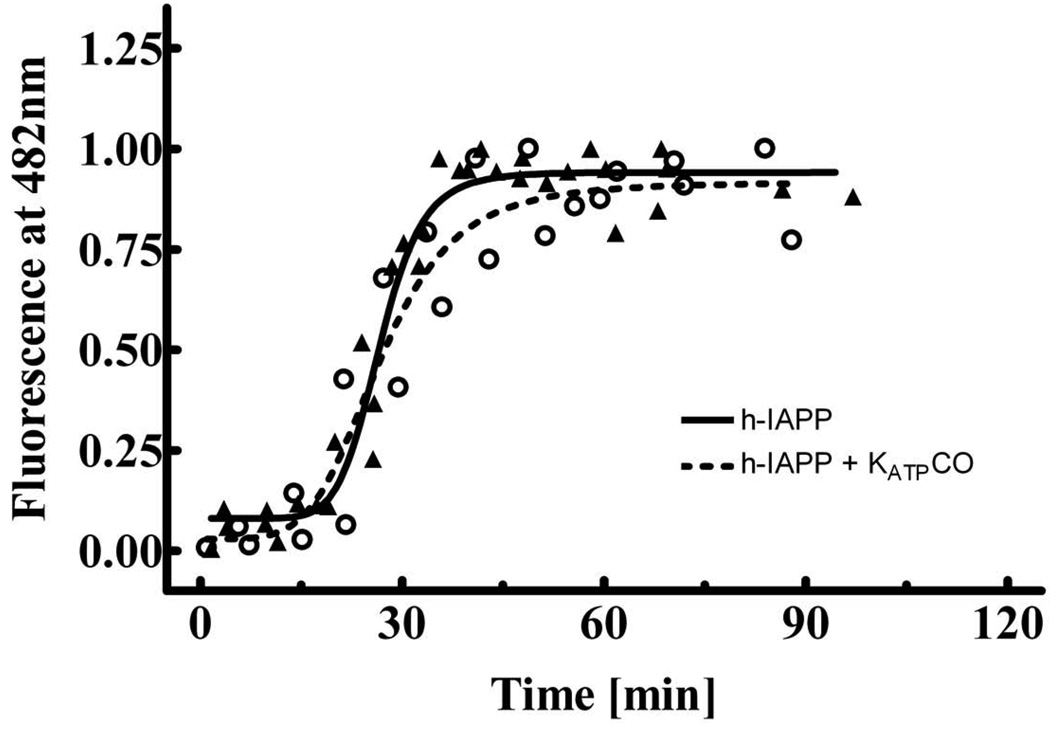

Thioflavin T binding assays (Fig. 5) show no change in the time course of h-IAPP aggregation by KATPCO suggesting that KATPCO does not directly alter the aggregation and formation of toxic IAPP oligomers.

Fig. 5.

Time-course of h-IAPP (20 µM) fibrillization with (n = 2 experiments) and without (n = 3 experiments) KATPCO (3 µM) in thioflavin T-binding assays. The solid and dashed lines are derived by non-linear regression analysis. The thioflavin T curves are normalized to the maximal observed intensity at the end of each aggregation reaction.

Discussion

In the present study we report that beta-cell selective activation of KATP-channels reduces apoptosis in beta-cells and isolated human islets induced by aggregating h-IAPP. Moreover we show that h-IAPP induced disintegration of human islet architecture is largely prevented. The latter observation implies that opening of beta-cell KATP-channels in human islets not only protects from h-IAPP induced cytotoxicity but also from h-IAPP induced disruption of cell-to-cell contacts, since we previously provided evidence that h-IAPP induced changes of islet architecture are also caused by disruption of cell coupling within human islets and lead to impaired insulin secretory capacity and a disturbed pulsatile release pattern [17]. Therefore the induction of beta-cell rest by opening of KATP-channels may be a useful strategy to reduce the toxicity of h-IAPP on beta-cells and islets.

The concept to protect beta-cells from chronic overstimulation by reducing their secretory activity has been initially established in the context of type 1 diabetes and later extended to type 2 diabetes [1; 2; 22–25]. Besides improvement of beta-cell function by replenishment of insulin stores it became evident that this approach might also protect beta-cells from cytotoxic attack. In a rat model of type 1 diabetes diazoxide and a beta-cell selective KATP-channel opener preserved beta-cell mass [26]. Studies with human islets provided direct evidence that beta-cell selective KATP-channel opening reduces glucose-induced apoptosis [19]. The present experiments add to this picture that reduced beta-cell secretory activity also protects from h-IAPP induced beta-cell apoptosis. Thus we hypothesize that the protective effect of beta-cell rest is unspecific and may protect from the various toxic influences on beta-cells in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The mechanism of protection by beta-cell rest has not been identified in detail. Overall reduction of beta-cell activity may be an important factor reducing the metabolic activity of the beta-cell (e.g. protein synthesis and shuttling through the endoplasmic reticulum), the upregulation of proapoptotic factors and the vulnerability of the beta-cell within a toxic metabolic milieu, which is characterized by increased expression of h-IAPP. Consistent with this hypothesis a recent study showed reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress by diazoxide in INS-1 cells incubated with palmitate [27]. In human islets ERK 1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) has been identified as a molecular target (reduced activation of ERK 1/2) of the beta-cell selective KATP-channel opening compound, which was also used in the present study [19]. It is unlikely that in the present experiments there is a direct interaction of the KATPCO compound with aggregating h-IAPP, since amyloid formation is unaltered in thioflavin T assays. Instead protection from apoptosis may be related to the fact that activation of KATP-channels probably reduces the cellular uptake of aggregating h-IAPP. Prior studies showed that exogenously applied aggregating amyloidogenic proteins are rapidly internalized into cells [28] and then accumulate in the intracellular compartment [13; 29]. These findings are consistent with endocytosis of the externally applied peptides. Exocytosis and endocytosis are both calcium dependent, this has been shown in various cell types [30]. Due to this coupling of endo- and exocytosis at the level of intracellular calcium (Cai) hyperpolarization of the cell membrane by KATP-channel opening and subsequent reduction of Cai would not only limit exocytosis but also endocytosis and consequently the internalization and cytotoxicity of applied IAPP. Further electrophysiologic studies are required to test this hypothesis on the single cell level. Since Cai is mechanistically involved in the induction of apoptosis by aggregating h-IAPP [31] the reduction of Cai by selective KATP-channel opening would also exert a protective effect on the apoptotic signaling pathways distal of Cai. So far it is unclear whether the initial aggregation of h-IAPP in human subjects occurs primarily intracellular, extracellular or at both sites. Therefore the impact of beta-cell rest on beta-cell apoptosis should also be studied in a model of endogenous h-IAPP toxicity (e.g. a rat model with transgenic expression of h-IAPP).

The aim of the present experiments was to test the underlying principle whether opening of KATP-channels protects from h-IAPP induced toxicity and experiments were performed over periods of 24–48 hours. In order to experimentally reproduce clinical application shorter and intermittent time intervals of beta-cell rest (≤12 hours) should be tested in future studies.

In conclusion, we provide evidence that beta-cell rest established by selective opening of beta-cell KATP-channels protects beta-cells and human islets from h-IAPP induced cytotoxicity. This effect is not due to a direct interaction of KATPCO with h-IAPP, but might be mediated through hyperpolarization of the beta-cell membrane induced by opening KATP channels. Therefore the concept of beta-cell rest may provide a strategy to protect beta-cells from h-IAPP induced apoptosis and to reduce progressive beta-cell loss and islet dysfunction in T2DM.

Acknowledgements

Human islets were obtained from the Human Islet Distribution Program, University of Minnesota, Diabetes Institute for Immunology and Transplantation (Dr. Bernhard J. Hering), and Northwest Tissue Center (Seattle, WA; Dr. R. Paul Robertson). IRB approval for islet isolation was obtained at each institution.

These studies were funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (Grant DK 61539 to P.C.B.), the Larry Hillbom Foundation (to P.C.B.) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG Ri 1055/1-1 and 1055/3-1 to R.A.R.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grill V, Bjorklund A. Overstimulation and beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2001;50:S122–S124. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2007.s122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritzel RA, Hansen JB, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Induction of beta-Cell Rest by a Kir6.2/SUR1-Selective K(ATP)-Channel Opener Preserves beta-Cell Insulin Stores and Insulin Secretion in Human Islets Cultured at High (11 mM) Glucose. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:795–805. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritzel RA. Therapeutic approaches based on beta-cell mass preservation and/or regeneration. Front Biosci. 2009;14:1835–1850. doi: 10.2741/3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laedtke T, Kjems L, Porksen N, Schmitz O, Veldhuis J, Kao PC, Butler PC. Overnight inhibition of insulin secretion restores pulsatility and proinsulin/insulin ratio in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:E520–E528. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.3.E520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maedler K, Spinas GA, Lehmann R, Sergeev P, Weber M, Fontana A, Kaiser N, Donath MY. Glucose induces beta-cell apoptosis via upregulation of the Fas receptor in human islets. Diabetes. 2001;50:1683–1690. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.8.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weir GC, Laybutt DR, Kaneto H, Bonner-Weir S, Sharma A. Beta-cell adaptation and decompensation during the progression of diabetes. Diabetes. 2001;50:S154–S159. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.2007.s154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poitout V, Robertson RP. Minireview: Secondary beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes--a convergence of glucotoxicity and lipotoxicity. Endocrinology. 2002;143:339–342. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.2.8623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H, Kouri G, Wollheim CB. ER stress and SREBP-1 activation are implicated in beta-cell glucolipotoxicity. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3905–3915. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02513. Epub 2005 Aug 3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark A, Cooper GJ, Lewis CE, Morris JF, Willis AC, Reid KB, Turner RC. Islet amyloid formed from diabetes-associated peptide may be pathogenic in type-2 diabetes. Lancet. 1987;2:231–234. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90825-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson KH, O'Brien TD, Betsholtz C, Westermark P. Islet amyloid, islet-amyloid polypeptide, and diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:513–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908243210806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butler AE, Janson J, Bonner-Weir S, Ritzel R, Rizza RA, Butler PC. Beta-cell deficit and increased beta-cell apoptosis in humans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:102–110. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janson J, Soeller WC, Roche PC, Nelson RT, Torchia AJ, Kreutter DK, Butler PC. Spontaneous diabetes mellitus in transgenic mice expressing human islet amyloid polypeptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7283–7288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janson J, Ashley RH, Harrison D, McIntyre S, Butler PC. The mechanism of islet amyloid polypeptide toxicity is membrane disruption by intermediate-sized toxic amyloid particles. Diabetes. 1999;48:491–498. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritzel RA, Butler PC. Replication increases beta-cell vulnerability to human islet amyloid polypeptide-induced apoptosis. Diabetes. 2003;52:1701–1708. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jayasinghe SA, Langen R. Membrane interaction of islet amyloid polypeptide. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:2002–2009. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.01.022. Epub 2007 Feb 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayed R, Head E, Thompson JL, McIntire TM, Milton SC, Cotman CW, Glabe CG. Common structure of soluble amyloid oligomers implies common mechanism of pathogenesis. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1079469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritzel RA, Meier JJ, Lin CY, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Human islet amyloid polypeptide oligomers disrupt cell coupling, induce apoptosis, and impair insulin secretion in isolated human islets. Diabetes. 2007;56:65–71. doi: 10.2337/db06-0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apostolidou M, Jayasinghe SA, Langen R. Structure of alpha-helical membrane-bound human islet amyloid polypeptide and its implications for membrane-mediated misfolding. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17205–17210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801383200. Epub 12008 Apr 17228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maedler K, Storling J, Sturis J, Zuellig RA, Spinas GA, Arkhammar PO, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Donath MY. Glucose- and interleukin-1beta-induced beta-cell apoptosis requires Ca2+ influx and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 activation and is prevented by a sulfonylurea receptor 1/inwardly rectifying K+ channel 6.2 (SUR/Kir6.2) selective potassium channel opener in human islets. Diabetes. 2004;53:1706–1713. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoshikawa H, Ma Z, Bjorklund A, Grill V. Short-term intermittent exposure to diazoxide improves functional performance of beta-cells in a high-glucose environment. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E1202–E1208. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00255.2004. Epub 2004 Aug 1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bedrood S, Jayasinghe S, Sieburth D, Chen M, Erbel S, Butler PC, Langen R, Ritzel RA. Annexin A5 directly interacts with amyloidogenic proteins and reduces their toxicity. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10568–10576. doi: 10.1021/bi900608m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenwood RH, Mahler RF, Hales CN. Improvement in insulin secretion in diabetes after diazoxide. Lancet. 1976;1:444–447. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortqvist E, Bjork E, Wallensteen M, Ludvigsson J, Aman J, Johansson C, Forsander G, Lindgren F, Berglund L, Bengtsson M, Berne C, Persson B, Karlsson FA. Temporary preservation of beta-cell function by diazoxide treatment in childhood type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2191–2197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.9.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guldstrand M, Grill V, Bjorklund A, Lins PE, Adamson U. Improved beta cell function after short-term treatment with diazoxide in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2002;28:448–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gier B, Krippeit-Drews P, Sheiko T, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J, Dufer M, Drews G. Suppression of KATP channel activity protects murine pancreatic beta cells against oxidative stress. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3246–3256. doi: 10.1172/JCI38817. doi: 3210.1172/JCI38817. Epub 32009 Oct 38811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skak K, Gotfredsen CF, Lundsgaard D, Hansen JB, Sturis J, Markholst H. Improved beta-cell survival and reduced insulitis in a type 1 diabetic rat model after treatment with a beta-cell-selective K(ATP) channel opener. Diabetes. 2004;53:1089–1095. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sargsyan E, Ortsater H, Thorn K, Bergsten P. Diazoxide-induced beta-cell rest reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress in lipotoxic beta-cells. J Endocrinol. 2008;199:41–50. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0251. Epub 2008 Jul 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Schubert D. Cytotoxic amyloid peptides inhibit cellular 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction by enhancing MTT formazan exocytosis. J Neurochem. 1997;69:2285–2293. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69062285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang AJ, Chandswangbhuvana D, Margol L, Glabe CG. Loss of endosomal/lysosomal membrane impermeability is an early event in amyloid Abeta1–42 pathogenesis. Journal of Neurosci Res. 1998;52:691–698. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980615)52:6<691::AID-JNR8>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hosoi N, Holt M, Sakaba T. Calcium dependence of exo- and endocytotic coupling at a glutamatergic synapse. Neuron. 2009;63:216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang CJ, Gurlo T, Haataja L, Costes S, Daval M, Ryazantsev S, Wu X, Butler AE, Butler PC. Calcium-activated calpain-2 is a mediator of beta cell dysfunction and apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. J Biol Chem. 2009;285:339–348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]