Abstract

Our previous studies have demonstrated increased expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) in fibrotic tissues and IGFBP-5 induction of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. The mechanism resulting in increased IGFBP-5 in the extracellular milieu of fibrotic fibroblasts is unknown. Since Caveolin-1 (Cav-1) has been implicated to play a role in membrane trafficking and signal transduction in tissue fibrosis, we examined the effect of Cav-1 on IGFBP-5 internalization, trafficking and secretion. We demonstrated that IGFBP-5 localized to lipid rafts in human lung fibroblasts and bound Cav-1. Cav-1 was detected in the nucleus in IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts, within aggregates enriched with IGFBP-5, suggesting a coordinate trafficking of IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 from the plasma membrane to the nucleus. This trafficking was dependent on Cav-1 as fibroblasts from Cav-1 null mice had increased extracellular IGFBP-5, and as fibroblasts in which Cav-1 was silenced or lipid raft structure was disrupted through cholesterol depletion also had defective IGFBP-5 internalization. Restoration of Cav-1 function through administration of Cav-1 scaffolding peptide dramatically increased IGFBP-5 uptake. Finally, we demonstrated that IGFBP-5 in the ECM protects fibronectin from proteolytic degradation. Taken together, our findings identify a novel role for Cav-1 in the internalization and nuclear trafficking of IGFBP-5. Decreased Cav-1 expression in fibrotic diseases likely leads to increased deposition of IGFBP-5 in the ECM with subsequent reduction in ECM degradation, thus identifying a mechanism by which reduced Cav-1 and increased IGFBP-5 concomitantly contribute to the perpetuation of fibrosis.

Keywords: caveolin-1, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5, fibrosis, extracellular matrix

Introduction

Fibrotic disorders, including systemic sclerosis (SSc) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), are characterized by excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as collagen and fibronectin (FN) [1, 2]. Fibrosis is the result of abnormal ECM remodelling which occurs due to an imbalance of ECM deposition and degradation [3, 4]. Activated fibroblasts are a primary source of ECM in fibrotic tissues [5]. Although numerous studies have explored the fibrotic process in different tissues, the exact pathogenic mechanism responsible for fibrosis in SSc and IPF has not been elucidated.

Caveolin-1 (Cav-1) is a 22-kD membrane protein essential for the formation of flask-shaped 50–100 nm membrane invaginations termed caveolae [6]. Since caveolae have a distinctive composition of lipids, including cholesterol and sphingolipids, they serve as a platform for processes such as trafficking, endocytosis and signalling [7–9]. Cav-1 was recently implicated in fibrosis. Kasper et al. first reported abnormal Cav-1 expression in type I pneumocytes during lung fibrogenesis [10]. Tourkina et al. subsequently identified a role for Cav-1 in regulating collagen expression in lung fibroblasts [11]. In addition, markedly decreased expression of Cav-1 in primary fibroblasts, lung and skin tissues of patients with SSc and IPF was reported [12, 13]. Several studies have shown that Cav-1 regulates a variety of signalling molecules and receptors, including Smad/transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor, Akt, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)/ERK (MEK), which interact with Cav-1 scaffolding domain (CSD) corresponding to amino acids 82–101 of Cav-1 [14–16]. Further confirmation for the role of Cav-1 in fibrosis was demonstrated in Cav-1 knockout mice, which exhibit a wide range of fibrosis-like lung abnormalities including thickening of lung alveolar septa and presence of hypertrophic type II pneumocytes [17, 18].

Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins (IGFBPs) were originally reported as regulators of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I function [19]. Secreted IGFBPs serve as carriers of IGF-I and modulate IGF-I actions, either potentiating or inhibiting them. Several studies have reported that IGFBPs also exert IGF-I-independent effects [20–23]. IGFBP-3 and -5 are the most abundant and conserved IGFBPs, respectively. They are secreted proteins which can also translocate to the nucleus via a nuclear localization sequence [24, 25]. Nuclear IGFBP-3 and -5 are believed to be derived from the corresponding secreted proteins, and their uptake by cells likely occurs through putative receptors which have not yet been identified [26].

We have previously reported that IGFBP-5 is significantly increased in dermal and pulmonary fibroblasts and tissues of patients with SSc and IPF [27, 28]. IGFBP-5 binds ECM components and its deposition in the extracellular milieu is increased in fibrotic cells and tissues [28]. Notably, IGFBP-5 induces the production of ECM components in vitro by IGF-I independent mechanisms [29, 30] and triggers a fibrotic phenotype in vivo[31] that includes induction of ECM production, myofibroblastic transformation and infiltration of mononuclear cells [29, 32]. Furthermore, IGFBP-5 triggers significant fibrosis in human skin using an ex vivo organ culture model [33].

In this study, we investigated the internalization and nuclear translocation of IGFBP-5 in association with Cav-1 in primary lung fibroblasts. Our findings demonstrate that IGFBP-5 binds Cav-1, is internalized via Cav-1-mediated pathways, and subsequently translocates to the nucleus as vesicular-like aggregates that lack a membrane and contain Cav-1. Further, IGFBP-5 is increased in the ECM of fibroblasts from Cav-1 null mice and likely protects ECM components from degradation. Thus, in fibrotic disorders such as SSc and IPF, reduced Cav-1 levels result in increased extracellular levels of IGFBP-5, which then contributes to fibrosis both by inducing ECM production and protecting ECM components from degradation.

Materials and methods

Primary fibroblast culture

Human primary lung fibroblasts were cultured under a protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board from the explanted lungs of normal organ donors. Mouse primary lung fibroblasts were cultured from lung tissues of C57BL/6J wild-type (WT) mice and Cav-1 null mice (Cav-1−/−) (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Approximately 2 cm pieces of peripheral lung were minced and fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Mediatech, Herndon, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin, streptomycin and anti-mycotic agent, as previously described [27].

Adenovirus construct preparation

Adenovirus constructs were generated as previously reported [28]. Briefly, the full-length cDNAs of human IGFBP-3 and -5 were obtained by RT-PCR using total RNA extracted from primary human fibroblasts. The cDNAs were subcloned into the shuttle vector pAdlox and used for the preparation of replication-deficient adenovirus serotype 5 expressing IGFBP-3 (Ad3), IGFBP-5 (Ad5), 3× FLAG®-tagged IGFBP-5 (Ad5-FLAG®) or, as a control, no cDNA (cAd) in the Vector Core Facility at the University of Pittsburgh. Replication-deficient adenovirus serotype 5 expressing mouse early growth response (Egr)-1 (AdEgr-1) was generously provided by Dr. John Varga (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA). Human and mouse primary lung fibroblasts were infected with adenovirus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50. In some experiments, supernatant from 3× FLAG-IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts (FLBP-5) was added to fibroblasts in culture. Briefly, fibroblasts were thoroughly rinsed with 1× PBS following infection with Ad5-FLAG® and cultured in fresh media. After 24 hrs, supernatants were harvested and centrifuged for 10 min. to pellet cell debris.

Purification of caveolae-enriched membrane fractions

Caveolae-enriched membrane fractions were purified as previously described [34]. Briefly, human lung fibroblasts were plated on 100 mm dishes and cultured for 48 hrs untreated or following infection with cAd or Ad5. Cells were homogenized in Triton-m-maleimidobenzoic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (MBS) buffer [25 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES), 150 mM NaCl, pH 6.5, 1% Triton X-100], adjusted to 40% sucrose by the addition of an equal volume of 80% sucrose, and overlaid with a 5–35% discontinuous sucrose gradient. The samples were centrifuged at 39,000 rpm for 18 hrs in an SW41 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Twelve fractions were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Immunoprecipitation

A total of 1.2 × 106 fibroblasts were cultured on 100 mm dishes and were either untreated or infected with cAd or Ad5 for 72 hrs and scraped in 350 μl radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Lysates were incubated with 2 μg Cav-1 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or control IgG at 4°C. A mixture of agarose beads conjugated with protein A and protein G (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were added for an additional 4 hrs. Bound complexes were washed with RIPA buffer and resuspended in 50 μl 2× SDS gel-loading buffer (125 mM Tris HCl, pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, 715 mM mercaptoethanol, 0.003% bromophenol blue) for Western blot analysis.

Transmission electron microscopy

Cells grown on tissue culture plastic were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM PBS (8 gm/l NaCl, 0.2 gm/l KCl, 1.15 gm/l Na2HPO4.7H2O, 0.2 gm/l KH2PO4, pH 7.4) for 1 hr at 4°C. Monolayers were washed in PBS three times and post-fixed in aqueous 1% osmium tetroxide, 1% Fe6CN3 for 1 hr. Cells were washed three times in PBS then dehydrated through a 30–100% ethanol series followed by several changes of Polybed 812 embedding resin (Polysciences, Warrington, PA, USA). Cultures were embedded by inverting Polybed 812-filled Better Equipment for Electron Microscopy (BEEM) capsules on top of the cells. Blocks were cured overnight at 37°C, and then cured for two days at 65°C. Monolayers were pulled off the plastic and re-embedded for cross-sectioning. Ultrathin cross-sections (60 nm) of the cells were obtained on a Riechart Ultracut E microtome, post-stained in 4% uranyl acetate for 10 min. and 1% lead citrate for 7 min. Sections were viewed on a JEOL JEM 1011 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Peabody, MA, USA) at 80 KV. Images were acquired with a side-mount AMT 2K digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA, USA).

Immunoelectron microscopy

Cells were fixed in cryofix (2% paraformaldehyde, 0.01% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PBS) and stored at 4°C for 1 hr. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in a small amount of 3% gelatin in PBS, solidified at 4°C, then fixed an additional 15 min. in cryofix. Gelatin-cell block was cryoprotected in polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) cryoprotectant overnight at 4°C (25% PVP, 2.3 M sucrose, 0.055 M Na2CO3, pH 7.4) as described previously [35]. Cell blocks were frozen on ultracryotome stubs under liquid nitrogen and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Ultrathin sections (70–100 nm) were cut using a Reichert Ultracut U ultramicrotome with a FC4S cryo-attachment, lifted on a small drop of 2.3 M sucrose and mounted on Formvar-coated copper grids. Sections were washed three times with PBS, then three times with PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.15% glycine (PBG buffer), followed by a 30 min. blocking incubation with 5% normal goat serum in PBG. Sections were labelled with anti-Cav-1 (BD transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY, USA) and anti-IGFBP-5 (Gropep Ltd., Adelaide, Australia) antibodies. Sections were washed four times in PBG and labelled with goat anti-rabbit (5 nm) or goat anti-mouse (10 nm) gold conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA), each at a dilution of 1:25 for 1 hr. Sections were washed three times in PBG, three times in PBS, then fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 5 min., washed two times in PBS and six times in ddH2O. Sections were post-stained in 2% neutral uranyl acetate, for 7 min., washed three times in ddH2O, stained 2 min. in 4% uranyl acetate, then embedded in 1.25% methyl cellulose. Labelling was observed on a JEOL JEM 1210 electron microscope at 80 kV.

Western blot analysis

Supernatants, cellular lysates and ECM were obtained from cultured fibroblasts as previously described [28] with some modifications. Briefly, 2.0 × 105 primary fibroblasts were cultured in 35 mm wells. Lysates were harvested using RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail. Cellular supernatants and lysates were resuspended in 6× SDS gel-loading buffer. ECM was scraped directly in 200 μl 2× SDS gel-loading buffer as previously described [28]. All samples were analysed by Western blot using one of following antibodies: anti-IGFBP-3, anti-Cav-1, anti-Egr-1, anti-FN, anti-type I collagen α1 chain, anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-human IGFBP-5 (Gropep Ltd.), anti-mouse IGFBP-5 (UBI, Lake Placid, NY), anti-α tubulin, anti-58k Golgi protein (Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-FLAG® M2 (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-Histone H3 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA) and anti-vitronectin (Bio genesis, Mill Creek, WA, USA). Signals were detected following incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

Preparation of fibroblast nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were extracted from cultured human and mouse fibroblasts as previously described [36]. Briefly, 1 × 106 fibroblasts were cultured in 100 mm dishes and scraped with 400 μl of Buffer A [10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES)-KOH pH 7.9, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.5 mM dithiotheitol, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF)]. Lysates were incubated on ice for 10 min. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 sec., supernatant (cytoplasmic extract) was harvested. The pellet was washed three times using 400 μl buffer A to remove any residual cytoplasmic extracts and resuspended in 100 μl Buffer C [20 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.9, 25% glycerol, 420 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.2 mM PMSF] on ice for 20 min. with intermittent vortexing. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 30 sec., supernatant (nuclear extract) was harvested. Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were stored at –80°C, and used for Western blot analysis.

Immunocytostaining

Human or mouse fibroblasts were cultured on cover slips coated with type I collagen (BD Biosciences, Belfold, MA, USA). After infection with adenoviral constructs for 48 hrs, cells were fixed for 20 min. in PBS containing 2% paraformaldehyde or methanol and acetone (1:1), and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Cover slips were blocked with 5% serum for 1 hr, and incubated with anti-IGFBP-5 (Gropep Ltd.) or anti-Cav-1 (BD transduction Laboratories) antibodies followed by Alexa Fluor® 488- or 555-conjugated donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies (Invitrogen). Appropriate IgG was used as a control antibody. Hoechst (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to identify nuclei. Images were taken on an Olympus Fluoview 1000 microscope (Olympus America, Inc., Melville, NY, USA) using identical camera settings.

IGFBP-5 degradation assay

A total of 2.0 × 105 WT and Cav-1−/− lung fibroblasts were seeded in 35 mm wells and cultured in serum-free medium for 24 hrs. Conditioned media were harvested and centrifuged to remove cell debris. Supernatants were mixed with recombinant IGFBP-5 protein (rBP5; final concentration 500 ng/ml), and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. A 6× SDS gel-loading buffer was added, and samples were subjected to Western blot analysis for the detection of IGFBP-5.

Detection of IGFBP-5 mRNA

IGFBP-5 and β-actin mRNA expression in cultured fibroblasts was examined using RT-PCR. Total RNA from WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts was extracted using TRIzol®. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using random primers and Superscript™ II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). IGFBP-5 and β-actin mRNAs were detected by PCR using cDNA (50 ng total RNA equivalent) as a template. Primer sets were forward: 5′-GAGGTGGTGACAGAGCAGGT-3′, reverse: 5′-TCTCGGAGTCTGGCTTTACC-3′ to amplify mouse IGFBP-5 (600 bp), and forward: 5′-ATGTTTGAGACCTTCAACAC-3′, reverse: 5′-CACGTCACACTTCATGATGG-3′ to amplify β-actin (494 bp). PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Disruption of caveolar structure

To disrupt caveolae, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD: Sigma-Aldrich) was used. Briefly, primary lung fibroblasts were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 mM MβCD for 1 hr at 37°C under serum-free conditions.

Silencing of Cav-1

Cav-1-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) was purchased from Applied Biosystems/Ambion (Austin, TX, USA). Scrambled siRNA was used as negative control. A total of 2.0 × 105 primary fibroblasts were seeded in 35 mm wells supplemented with DMEM containing 10% FBS but no antibiotics. Cells were transfected with 100 pmol siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and cultured for 48 hrs prior to harvesting.

Treatment with Cav-1 scaffolding peptide

A peptide corresponding to the CSD (amino acids 82–101 of Cav-1; DGIWKASFTTFTVTKYWFYR) and a scrambled control peptide (Cont: WGIDKAFFTTSTVTYKWFRY), carrying the antennapedia internalization sequence (RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK), were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Human lung fibroblasts at 70–80% confluence were cultured for 16 hrs in serum-free DMEM then treated with 5 μM CSD or Control peptide as previously described [16] for 1 hr. Cells were harvested and used for immunoblotting.

ECM degradation assay

Cell culture wells were coated with human FN (Sigma-Aldrich) at 1 μg/cm2. Human recombinant IGFBP-5 (Gropep Ltd.) or vehicle (10 mM HCl) was added to the wells and incubated at 4°C for 16 hrs to allow IGFBP-5 to bind FN. The wells were washed with 1× PBS prior to the addition of media conditioned by the culture of normal fibroblasts. Conditioned media were mixed with or without the following protease inhibitors: 10 mM PMSF, 10 mM EDTA, and protease inhibitor cocktail (PI; Sigma-Aldrich), agitated on a shaker for 6 hrs at 37°C, then added to the wells for 48 hrs. ECM was harvested and used for immunoblotting.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using the paired or unpaired Student’s t-test as appropriate.

Results

IGFBP-5 localizes to caveolin-1-enriched fractions and binds to caveolin-1

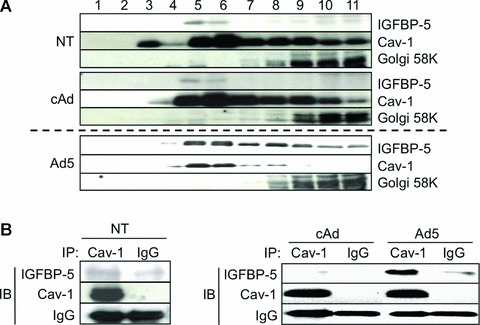

We first examined whether IGFBP-5 localized to caveolin-enriched fractions in untreated and IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts. As shown in Figure 1A, IGFBP-5 was detected in Cav-1 containing cellular fractions (fractions 4–6). IGFBP-5 levels in these fractions were more modest in untreated compared to IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts, indicating that IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 co-localize in lipid rafts. To determine whether IGFBP-5 binds Cav-1 in human fibrob lasts, co-precipitation assays were used. As shown in Figure 1B, IGFBP-5 co-precipitated with Cav-1 in both untreated (left panel) and IGFBP-5 expressing (right panel) fibroblasts, demonstrating that IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 form protein complexes at baseline and under high IGFBP-5 expression conditions.

Fig 1.

The localization and binding of Cav-1 and IGFBP-5. (A) Caveolae-enriched membrane fractionation was analysed by immunoblotting for IGFBP-5 and Cav-1. Twelve fractions were obtained from human lung fibroblasts that were infected with cAd, Ad5 or untreated (NT) for 48 hrs using sucrose density gradient fractionation. Eleven fractions (fractions 1–11) were subjected to Western blot analysis for IGFBP-5, Cav-1 and 58k Golgi protein as a control for the fractionation. Different exposure times for NT, cAd and Ad5 are shown as the levels of IGFBP-5 in Ad5 samples were high and the signal was easily saturated. (B) Protein-protein interaction between IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 was examined by immunoprecipitation. Primary lung fibroblasts were NT or infected with Ad5 or cAd at an MOI of 50 and cellular lysates were harvested 72 hrs after treatment. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Cav-1 antibody or rabbit IgG (IgG). Co-precipitation of IGFBP-5 was examined by immunoblotting (IB). Cav-1 and rabbit immunoglobulins are shown as controls. Left panel: NT cells. Right panel: cAd- or Ad5-infected cells.

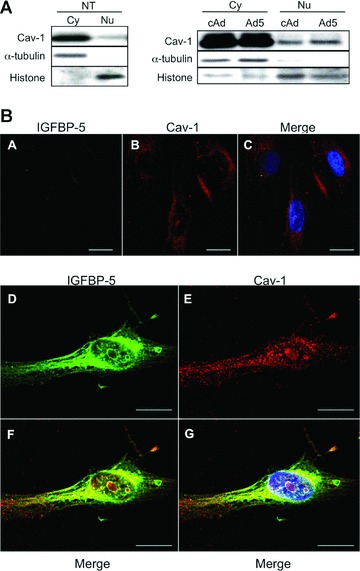

Caveolin-1 translocates to the nucleus in IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts

Since IGFBP-5 is a secreted protein that translocates to the nucleus to exert its transcription-regulatory activity [20], we speculated that the interaction of Cav-1 with IGFBP-5 on the cell membrane may result in nuclear trafficking of both proteins. We therefore examined Cav-1 levels in nuclear extracts of IGFBP-5-expressing primary fibroblasts. As shown in Figure 2A, the relative distribution of Cav-1 in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of non-treated (NT: left panel) and cAd-treated (right panel) primary fibroblasts was comparable. In contrast, Cav-1 levels were 40% greater in nuclear extracts of IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 2A, right part). The nuclear localization of Cav-1 was further confirmed using immunofluorescence. Immunocytostaining of Cav-1 and IGFBP-5 revealed the presence of Cav-1 in the nuclei of IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 2B). Since Jurgeit et al. had reported that IGFBP-5 is present in intracellular vesicles outside the nucleus [37], we extended our confirmation of Cav-1 and IGFBP-5 co-localization and nuclear translocation using electron microscopy (Fig. 3). Vesicle-like structures were detected in the cytoplasm and the nucleus of IGFBP-5 expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 3B–F) but were not present in control fibroblasts (Fig. 3A). Extensive analysis of these vesicle-like structures revealed the absence of a membrane, suggesting that they consisted of protein aggregates. Upon entry in these nucleus, aggregates of various sizes seemed to fuse and form larger and denser aggregates (Fig. 3C–F). Using immuno-electron microscopy, we confirmed that both Cav-1 and IGFBP-5 are components of these aggregates in IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts (Fig. 3G–L).

Fig 2.

Nuclear translocation of Cav-1 in IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts. (A) A total of 1 × 106 human lung fibroblasts were cultured on 100 mm dishes and untreated or infected with cAd or Ad5 at an MOI of 50. After 24 hrs, cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared and expression of Cav-1 was examined by Western blot. Cytoplasmic extracts from 5 × 104 cell-equivalent or nuclear extracts from 1 × 105 cell-equivalent was applied to each lane. α-tubulin is shown as a loading control for cytoplasmic extracts, and histone for nuclear extracts. Left panel: NT cells. Right panel: cAd- or Ad5-infected cells. (B) Expression of IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 was examined by immunofluorescence. Human lung fibroblasts were cultured on cover slips coated with type I collagen. After infection using cAd (A–C) or Ad5 (D–G) for 48 hrs, cells were stained for IGFBP-5 (green) and Cav-1 (red). Hoechst (blue) was used to identify nuclei. Magnification of images ranged from 800× to 1000× on a confocal microscope. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Fig 3.

Detection of IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 in nuclei by electron microscopy. (A–F) Human lung fibroblasts were infected with cAd (A) or Ad5 (B–F) for 48 hrs, fixed, and analysed by transmission electron microscopy. Cy: cytoplasm; Nu: nucleus; *: aggregates. (G–L) Ad5-infected human fibroblasts subjected to immuno-TEM. (H) and (I) represent magnified regions of the nucleus shown in (G). (J–L) show higher magnification of gold particles detected in inclusions and protein aggregates in the nucleus. Ten nanometre gold particles (white arrow) identify Cav-1, and 5 nm gold particles (representative white arrowheads) identify IGFBP-5. Size of bars is indicated.

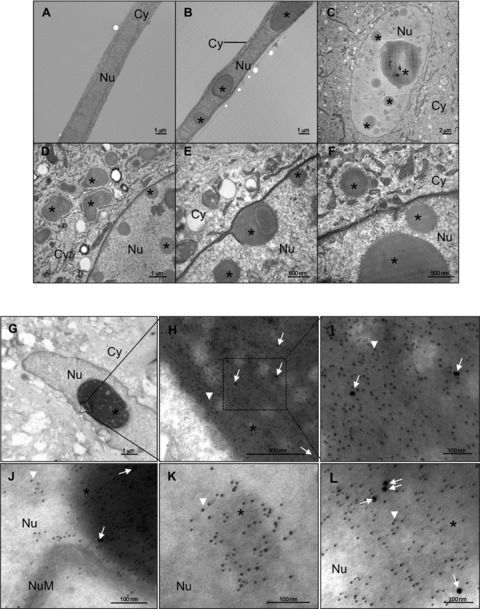

IGFBP-5 compartmentalization is altered in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts purified from caveolin-1 deficient fibroblasts

We next sought to determine whether Cav-1 is required for IGFBP-5 nuclear translocation. Levels of IGFBP-5 were compared in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from IGFBP-5-expressing WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. As shown in Figure 4C and F, compared to WT fibroblasts, Cav-1−/− fibroblasts had significantly lower levels of IGFBP-5 in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. Similar results were observed for IGFBP-3 in Cav-1−/− fibroblasts infected with Ad3 (Fig. 4D and F). To exclude the possibility that Cav-1 deficiency prevents efficient adenoviral infection, we infected the fibroblasts with an adenovirus expressing human Egr-1, a transcription factor known to localize to the nucleus [38]. Egr-1 levels were comparable in nuclear extracts from WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts (Fig. 4E and F), suggesting that reduced IGFBP nuclear translocation in Cav-1 null fibroblasts is not due to hindrance of adenoviral infection and that nuclear compartmentalization of IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 requires Cav-1.

Fig 4.

IGFBP-5 (A–C), IGFBP-3 (D) and Egr-1 (E) levels in cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts from WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were extracted from WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts that were untreated or infected with the indicated adenoviral constructs for 48 hrs. Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were subjected to immunoblotting for the detection of IGFBP-5, IGFBP-3 and Egr-1. α-tubulin is shown as a loading control for cytoplasmic extracts, and histone for nuclear extracts. (F) Graphical summary of data shown in parts (B–E). The signal intensity of each protein in nuclear extracts was normalized to histone, and the ratio of the intensity in Cav-1−/− to WT was calculated. Differences in levels between WT and Cav-1−/− cells were compared using the unpaired t-test. Horizontal bars indicate mean values of two independent experiments. **P < 0.01.

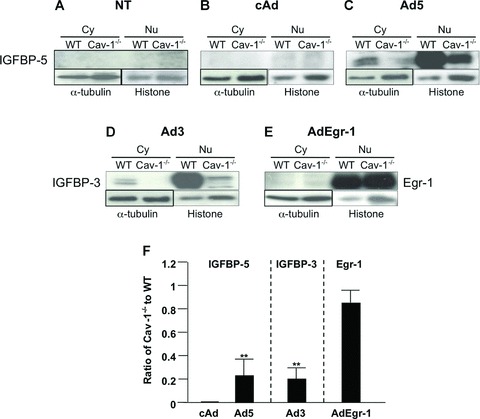

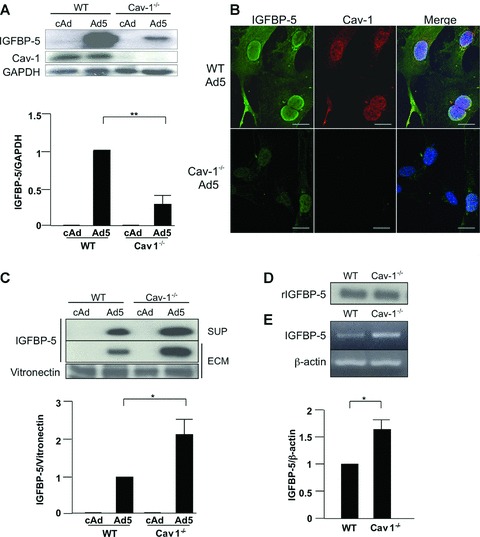

Absence of caveolin-1 is associated with low intracellular and high extracellular levels of IGFBP-5

Having observed a lack of IGFBP-5 in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of IGFBP-5-expressing Cav-1−/− fibroblasts, we compared intracellular IGFBP-5 levels to those secreted and deposited in the ECM. As shown in Figure 5A, IGFBP-5 levels were significantly reduced in lysates of Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. This was further confirmed using immunocytochemistry (Fig. 5B). In contrast to cellular lysates, IGFBP-5 levels in the extracellular milieu in both media conditioned by IGFBP-5 expressing Cav-1−/− fibroblasts and the ECM deposited by the cells were higher than those in their WT counterparts (Fig. 5C). IGFBP-5 can be proteolytically cleaved by several different proteases, and increased extracellular levels of IGFBP-5 can result from reduced IGFBP-5 degradation. To compare IGFBP-5 degradation in WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts, we used a degradation assay. As shown in Figure 5D, levels of intact rBP5 were comparable in the presence of media conditioned by WT and Cav-1−/−, indicating that the absence of Cav-1 does not modulate the extracellular degradation of IGFBP-5. To further evaluate the effects of Cav-1 on IGFBP-5 expression, we examined steady-state mRNA levels of IGFBP-5 in WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. At baseline, Cav-1−/− lung fibroblasts had significantly higher IGFBP-5 mRNA levels compared to WT cells (Fig. 5E), likely a compensatory response to the reduced intracellular protein levels of IGFBP-5 in Cav-1−/− fibroblasts.

Fig 5.

IGFBP-5 levels in lysates, supernatants and ECM of WT and Cav-1−/− lung fibroblasts. Cultured WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts were infected with cAd and Ad5 at an MOI of 50. Lysates, supernatants and ECM were harvested after 48 hrs (A) or 72 hrs (C). Levels of IGFBP-5 were analysed by immunoblotting of lysates (A), supernatants (SUP) and ECM (C). GAPDH and vitronectin were used as loading controls for lysates and ECM, respectively. For the supernatant, an equivalent amount of total protein was loaded in each lane. Graphical summary of IGFBP-5 expression in lysates (A) and ECM (C) from WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. Horizontal bars indicate mean values of three independent experiments for (A) and two independent experiments for (C). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (B) IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 localization was examined by immunocytostaining. WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts were cultured on cover slips coated with type I collagen. After infection with Ad5 for 48 hrs, cells were stained for IGFBP-5 (green) and Cav-1 (red). Hoechst (blue) was used to identify nuclei. Magnification of images was 600× on a confocal microscope. Scale bars = 20 μm. (D) Western blot analysis of rIGFBP5 levels following 1 hr incubation with media conditioned by WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. (E) Steady-state mRNA levels of mouse IGFBP-5 in NT, WT, and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. β-actin was used as a control. Normalized IGFBP-5 mRNA levels in WT were arbitrarily set at 1. Horizontal bars indicate mean values of three independent experiments. The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis.

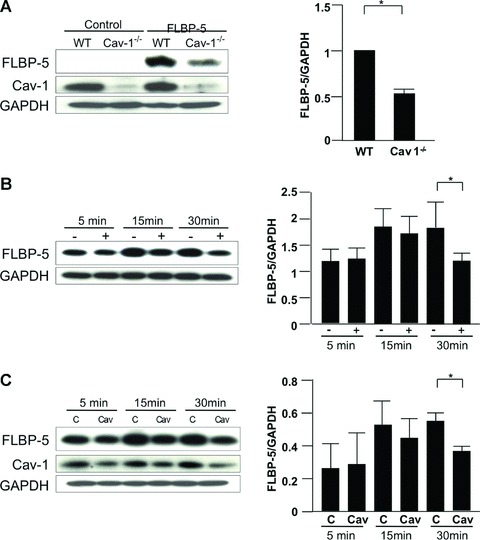

Caveolin-1 regulates nuclear compartmentalization of IGFBP-5

Increased levels of extracellular IGFBP-5 and decreased intracellular levels in Cav-1−/− mouse fibroblasts led us to speculate that Cav-1 might regulate the internalization of secreted IGFBP-5. To determine if secreted IGFBP-5 requires Cav-1 for internalization, 3× FLAG-tagged IGFBP-5 (FLBP-5) secreted by WT fibroblasts was added to WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. After 15 min., IGFBP-5 levels corresponding to internalized protein were detected in cellular lysates using anti-FLAG antibody. As shown in Figure 6A, Cav-1−/− fibroblasts had lower intracellular IGFBP-5 levels compared with WT fibroblasts, indicating that Cav-1 facilitates IGFBP-5′s internalization. To differentiate caveolin-containing caveolae from lipid rafts, we disrupted fibroblast lipid rafts with MβCD. To reduce Cav-1 levels and emulate those in fibrotic disease, we also silenced Cav-1 expression using sequence-specific siRNA. Silencing Cav-1 resulted in a 52% reduction in corresponding protein levels. Purified 3× FLAG-tagged IGFBP-5 was then added to these fibroblasts, and lysates were harvested after 5, 15 and 30 min. Tagged IGFBP-5 was detected using anti-FLAG antibody. Whereas uptake of tagged IGFBP-5 increased in a time-dependent manner in control fibroblasts, lower levels of IGFBP-5 were observed in lysates of fibroblasts treated with MβCD and those in which Cav-1 was silenced 15 and 30 min. following the addition of FLAG-tagged IGFBP-5 (Fig. 6B, C). The decrease in IGFBP-5 uptake reached significance at 30 min. (Fig. 6B and C, right panels). Depletion of cholesterol and silencing of Cav-1 both reduced cellular uptake of IGFBP-5, suggesting that both Cav-1 and intact caveolae contribute to the internalization of IGFBP-5.

Fig 6.

Internalization of IGFBP-5. (A) WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts were plated at 70% confluence in serum-free media. FLAG-tagged IGFBP-5 (FLBP-5) was added to each well. After 15 min., lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis. IGFBP-5 in lysates from WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts was detected using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Normalized FLBP-5 levels in WT fibroblasts were arbitrarily set at 1. Horizontal bars indicate mean values of two independent experiments. The unpaired t-test was used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05. (B) WT fibroblasts were cultured with (+) or without (-) 10 mM MβCD for 1 hr in serum-free media, and FLBP-5 was added to each well. After 5, 15 and 30 min., lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis. IGFBP-5 in lysates was detected using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Horizontal bars indicate mean values of three independent experiments. Data were analysed using the paired t-test. *P < 0.05. (C) WT fibroblasts were transfected with control scrambled siRNA (C) or siCav-1 (Cav) for 48 hrs, and then FLBP-5 was added to each well. After 5, 15 and 30 min., lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis. IGFBP-5 in lysates was detected using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Horizontal bars indicate mean values of three independent experiments. Data were analysed using the paired t-test. *P < 0.05.

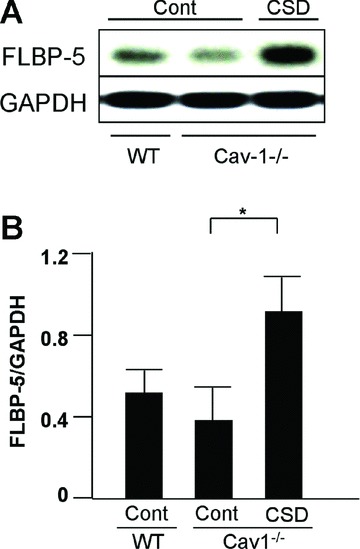

IGFBP-5 trafficking can be restored by restitution of Cav-1 function

The Cav-1 CSD peptide can bind to a variety of proteins, and restoration of Cav-1 function can be accomplished by delivery of Cav-1 CSD [39]. We used a cell-permeable Cav-1 CSD peptide at concentrations shown by others to restore Cav-1 function [12, 16], to evaluate whether restoration of Cav-1 function facilitates normal uptake of IGFBP-5. Briefly, Cav-1−/− fibroblasts were treated with 5 μM Cav-1 CSD peptide for 1 hr, and then purified FLAG-tagged IGFBP-5 was added. Fibroblasts were harvested and IGFBP-5 levels were detected by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 7, restoration of Cav-1 function in Cav-1−/− fibroblasts using Cav-1 CSD peptide dramatically increased IGFBP-5 internalization, thus restoring IGFBP-5 trafficking.

Fig 7.

IGFBP-5 uptake following restoration of Cav-1 function. (A) WT or Cav-1−/− fibroblasts were treated with Cav-1 CSD peptide (CSD) or control peptide (Cont) for 1 hr in serum-free medium, then FLAG-tagged IGFBP-5 (FLBP-5) was added. After 15 min., lysates were harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis. IGFBP-5 levels in lysates were detected using anti-FLAG M2 antibody. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (B) Graphical analysis of IGFBP-5 levels in lysates of WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts following 1 hr incubation with Cav-1 CSD (CSD) or control peptide (Cont). Horizontal bars indicate mean values from four independent experiments. The paired t-test was used for statistical analysis. *P < 0.05.

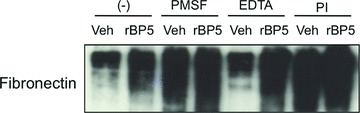

IGFBP-5 protects ECM components from degradation

We have previously demonstrated increased expression, secretion, and ECM deposition of IGFBP-5 in primary fibroblasts from patients with SSc and IPF [27, 28]. We have also reported that IGFBP-5 induces production of collagen and FN and binds these ECM components [28]. In addition, we and others have reported reduced levels of Cav-1 in primary fibroblasts from patients with SSc and IPF [12, 13]. In view of these findings, we speculated that increased IGFBP-5 deposition in the ECM of fibrotic cells resulted from impairment of IGFBP-5 cellular entry due to low expression of Cav-1. We therefore explored the possibility that in cells with reduced Cav-1 levels, IGFBP-5 deposited in the ECM could protect ECM components from degradation, thus contributing to the fibrotic phenotype. Human rBP5 was added to FN-coated plates and allowed to bind overnight. Media conditioned by fibroblasts, presumed to be a source of proteases that can degrade ECM components, was added to the IGFBP-5-bound FN in the presence or absence of protease inhibitors. After 48 hrs, ECM was harvested and FN levels were examined by immunoblotting using an antibody that recognizes the EDA-containing domain specific to matrix FN. As shown in Figure 8, FN levels in rBP5-bound FN-coated wells were notably higher than those in vehicle treated FN-coated wells, confirming our previous observations [28] and establishing that IGFBP-5 can bind to FN and afford it protection from proteolytic activity. In the presence of conditioned media supplemented with PMSF and protease inhibitor cocktail-, but not EDTA-treated supernatants, FN levels in the ECM were higher, suggesting that FN was protected from degradation. Although degraded FN fragments could not be detected using the FN antibody, taken together, our results indicate that IGFBP-5-bound FN in ECM is protected from proteolytic degradation.

Fig 8.

ECM degradation assay. Cell culture wells were coated with human plasma FN. Recombinant IGFBP-5 (rBP5) or vehicle (Veh; 10 mM HCL) was added for an additional 16 hrs. Medium conditioned by primary fibroblasts was added to the wells in the presence or absence of the protease inhibitors PMSF, EDTA and PI (protease inhibitor cocktail). After 48 hrs, ECM was harvested and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Discussion

Our goal was to evaluate the association of Cav-1 and IGFBP-5 and the role of Cav-1 in IGFBP-5 internalization in lung fibroblasts and thus elucidate the pathogenic mechanism mediating fibrosis as a result of reduced Cav-1 expression. In primary fibroblasts, IGFBP-5 bound Cav-1 and both proteins translocated to the nucleus in IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts. Electron microscopy revealed the presence of IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 within aggregates in the nucleus. Caveolar disruption and Cav-1 silencing inhibited IGFBP-5 internalization. Conversely, restoration of Cav-1 function using Cav-1 CSD peptide facilitated cellular uptake of IGFBP-5 in Cav-1−/− fibroblasts. Accumulation of secreted IGFBP-5 in the ECM of Cav-1−/− fibroblasts increased as intracellular levels decreased. Steady-state mRNA levels of mouse IGFBP-5 increased in Cav-1−/− fibroblasts, probably reflecting a compensatory mechanism in response to reduced intracellular levels of IGFBP-5 protein. Unlike mRNA levels, the degradation of IGFBP-5 in the extracellular milieu was similar in WT and Cav-1−/− fibroblasts, suggesting that inhibition of proteolytic cleavage does not explain the increased extracellular deposition of IGFBP-5 in the absence of Cav-1.

In primary pulmonary fibroblasts, IGFBP-5 co-localized with Cav-1 and both proteins formed complexes. In addition, Cav-1 CSD peptide significantly increased the intracellular uptake of IGFBP-5, suggesting an interaction between the CSD peptide and IGFBP-5. In other words, IGFBP-5 might be a direct target of Cav-1 or could be an indirect target as a Cav-1-bound protein. In this regard, the consensus sequences of CSD peptide ligands have been identified [40]. The sequences, ϕXϕXXXXϕ, ϕXXXXϕXXϕ and ϕXϕXXXXϕXXϕ, where ϕ is any of the aromatic acids (F, W or Y) and X is any amino acid, are the first described as Cav-1 binding domains responsible for the interaction of Cav-1 with other proteins. Signalling molecules, G-protein receptors and growth factor receptors, including mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, eNOS, endothelin R, epidermal growth factor (EGF)-R and IGFBP-3 that are known to be caveolin-associated proteins, contain these motifs [40, 41]. Broader consensus Cav-1 binding sequences, in which a hydrophobic amino acid (I, V or L) replaces aromatic acids in addition to F, W or Y, were subsequently reported [42]. We speculate that IGFBP-5 might be a direct target of Cav-1 since IGFBP-5 contains the sequence ICWCVDKY247, an imperfect consensus sequence with homology to ϕXZXXXXϕ or ZXXXXϕXXZ, where Z stands for F, W, Y, I, V or L.

Nuclear translocation of IGFBP-3 and IGFBP-5 has been reported in vascular smooth muscle cells, T47D human breast carcinoma cells and Chinese hamster ovary cells [20, 24, 25]. Since inhibition of protein secretion abolished IGFBP nuclear localization, it was deduced that nuclear IGFBP-3 and -5 are derived from the secreted proteins [20, 41]. We have also reported that nuclear translocation of IGFBP-5 occurs in a time-dependent, MAPK-dependent and IGF-I independent manner [30]. The internalization and nuclear transport of IGFBP-3, a protein with significant homology to IGFBP-5 containing a nuclear localization sequence, is documented in a variety of cells and includes caveolin- and clathrin-dependent pathways [24, 25, 41]. However, pathways mediating the internalization of IGFBP-5 have not been reported, especially in primary cells such as fibroblasts. Our current study identified the caveolin pathway as a mediator of IGFBP-5 internalization in primary fibroblasts. It is not likely that the caveolin-dependent pathway is the sole mediator of IGFBP-5 uptake, since neither caveolar disruption nor absence of Cav-1 completely inhibited IGFBP-5 uptake. As both caveolin- and transferrin-mediated endocytosis are responsible for IGFBP-3 internalization [41], other pathways, including the transferrin-dependent classical pathway [43] and heparan sulphate proteoglycan-associated internalization [44] may also be involved in IGFBP-5 endocytosis. The latter is likely based on the ability of IGFBP-5 to interact with heparan sulphate proteoglycans [45].

Electron microscopy revealed the presence of cytoplasmic and nuclear aggregates composed mainly of IGFBP-5 in IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts. Interestingly, Cav-1 was also detected inside these aggregates, suggesting that they may have originated from the plasma membrane. This suggests a scenario whereby secreted IGFBP-5 was taken up into caveolae, which subsequently formed intracellular vesicle-like structures that trafficked to the nucleus. Our finding is in partial agreement with a recent report showing that IGFBP-5 is found in vesicular structures in T47D cells [37]. However, in this report, IGFBP-5-containing vesicles were not detected in the nucleus. Thus unlike the observations in T47D cells, we clearly show using electron microscopy that IGFBP-5 translocates to the nuclear compartment in inclusions that lack a membrane and are not true vesicles. The fact that IGFBP-5 forms multimers [46] may explain, at least in part, its ability to form aggregates. The differences between our observations and those of Jergeit et al. may be attributed to the cell types as they used immortalized cancer cell lines whereas we used primary fibroblasts, or the use of replication-deficient adenovirus to drive the expression of IGFBP-5 in our system. However the latter is unlikely as expression of IGFBP-3 using the same adenoviral construct did not result in the formation of vesicles or aggregates (data not shown). One of the limitations of immuno-electron microscopy used to confirm the presence of IGFBP-5 and Cav-1 in the nucleus is that detection of proteins is limited to those that are abundant as sections (70 nm) are notably thinner than those use for immunohistochemistry or immunofluorescence staining (6 μM). Thus, although few 10 nm gold particles identifying Cav-1were detected, the shear presence of these particles suggests that Cav-1 is abundant in the nuclei of IGFBP-5-expressing fibroblasts.

Although Cav-1 is a major membrane protein, our data demonstrate that Cav-1 is also localized in the nucleus. Several studies support our findings. For example, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces nuclear translocation of Flk-1/KDR, eNOS and Cav-1 in vascular endothelial cells [47]. Increased nuclear localization of Cav-1 was also reported in human diploid fibroblasts in H2O2-induced premature senescence [48]. Furthermore, Dittmann et al. reported that Cav-1 dependent EGF-R internalization was induced by irradiation in a src-dependent manner, and subsequently Cav-1 and EGF-R were shuttled into the nucleus and induced DNA damage [49]. Likewise, Cav-1 mediates the internalization and nuclear compartmentalization of several proteins, and likely has a regulatory function. Thus, the role of nuclear Cav-1, in conjunction with the pro-fibrotic activity of IGFBP-5, is novel and warrants further exploration.

Since it has been reported that IGFBP-5 can interact with several ECM components, including FN, collagen and proteoglycans [28, 45, 50], we performed an ECM degradation assay to explore the effects that reduced Cav-1 levels and resulting increased extracellular IGFBP-5 deposition have on the fibrotic phenotype. Our results show that IGFBP-5 bound FN in the ECM and as a result protected FN from proteolytic degradation in vitro. Recently, decreased Cav-1 expression in skin and lung fibroblasts of patients with SSc and IPF has been reported [12, 13]. Furthermore, we have reported increased IGFBP-5 in fibroblasts, skin and lung tissues from patients with these same diseases [27, 28]. We now show that Cav-1 deficiency results in increased deposition of secreted IGFBP-5 in the ECM and that this IGFBP-5 can bind ECM components and prevent their degradation. Our findings establish a mechanism by which decreased Cav-1 and increased IGFBP-5 in concert promote the progression and perpetuation of fibrosis. We thus propose a scenario where SSc and IPF fibroblasts secrete IGFBP-5 [27, 28]. Secreted IGFBP-5 induces production of collagen and FN [29] and accumulates in the ECM due to inefficient internalization in fibrotic cells that have reduced Cav-1 levels [12, 13]. Extracellular IGFBP-5 binds components of the ECM and protects them from proteolytic degradation, thus perpetuating the accumulation of ECM components and supporting the fibrotic phenotype. In addition, we recently reported that IGFBP-5 has a chemoattractant activity and promotes the migration of mononuclear cells into lung tissues [29, 30, 32] and the transition of fibroblasts and epithelial cells to a myofibroblastic phenotype [29–32]. Both immune cell infiltration and the activation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts are implicated in the development of fibrosis. Thus, IGFBP-5 contributes to the fibrotic phenotype via promoting the production and deposition of ECM components, protecting ECM components from degradation, the recruitment of mononuclear cells and fibroblasts, and the activation of fibroblasts.

Restoration of Cav-1 function using Cav-1 CSD peptide has been suggested as a potential therapeutic strategy in SSc and IPF patients [16], as Cav-1 inhibits TGF-β signalling by promoting the degradation of the TGF-β receptor and preventing Smad 2 phosphorylation [14]. Systemic administration of Cav-1 CSD peptide to bleomycin-treated mice dramatically inhibited epithelial cell apoptosis, inflammatory cell infiltration, activation of signalling molecules, and expression of ECM components [16]. In our study, treatment with Cav-1 CSD peptide induced rapid uptake of extracellular IGFBP-5, thus reducing extracellular levels of IGFBP-5. Taken together, these findings suggest that administration of Cav-1 CSD peptide may have beneficial effects in fibrosis. However, in contrast to fibroblasts, an increase of Cav-1 expression in endothelial cells was reported during lung fibrogenesis [10]. In addition, pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells from patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension have increased Cav-1 levels which contributes to pulmonary artery smooth muscle cell proliferation and hypertrophy of the pulmonary vascular wall [51], an effect opposite the phenotype described in Cav-1 null mice [17, 18]. Thus, as for any potential therapy tested in vitro and in vivo in animals, a therapeutic approach using CSD peptide should be explored cautiously.

In summary, we show that IGFBP-5 is internalized via Cav-1 containing lipid rafts and traffics to the nucleus in vesicular-like inclusions. IGFBP-5 deposition in the ECM is accentuated in Cav-1-deficient lung fibroblasts, promoting the fibrotic phenotype by supporting the accumulation of IGFBP-5 in the extracellular milieu and its binding to components of the ECM, thus preventing their degradation. As decreased expression of Cav-1 in fibroblasts from SSc and IPF patients has been reported [12, 13], our findings provide new insights into mechanisms used by IGFBP-5 to induce and promote fibrosis and the role of Cav-1 in the compartmentalization and trafficking of IGFBP-5.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grant AR050840 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Katie Clark and Mara Sullivan for technical assistance with electron microscopy.

References

- 1.Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr Severe organ involvement in systemic sclerosis with diffuse scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:2437–44. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200011)43:11<2437::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katzenstein AL, Myers JL. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: clinical relevance of pathologic classification. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1301–15. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9707039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardo A, Selman M. Matrix metalloproteases in aberrant fibrotic tissue remodeling. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:383–8. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-012TK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu X, Wu H, Byrne M, et al. A targeted mutation at the known collagenase cleavage site in mouse type I collagen impairs tissue remodeling. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:227–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Varga J, Abraham D. Systemic sclerosis: a prototypic multisystem fibrotic disorder. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:557–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI31139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada E. The fine structure of the gall bladder epithelium of the mouse. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1955;1:445–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.1.5.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlegel A, Pestell RG, Lisanti MP. Caveolins in cholesterol trafficking and signal transduction: implications for human disease. Front Biosci. 2000;5:D929–37. doi: 10.2741/schlegel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parton RG, Richards AA. Lipid rafts and caveolae as portals for endocytosis: new insights and common mechanisms. Traffic. 2003;4:724–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galbiati F, Razani B, Lisanti MP. Emerging themes in lipid rafts and caveolae. Cell. 2001;106:403–11. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00472-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasper M, Reimann T, Hempel U, et al. Loss of caveolin expression in type I pneumocytes as an indicator of subcellular alterations during lung fibrogenesis. Histochem Cell Biol. 1998;109:41–8. doi: 10.1007/s004180050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tourkina E, Gooz Pal, Pannu J, et al. Opposing effects of protein kinase Cα and protein kinase Cɛ on collagen expression by human lung fibroblasts are mediated via MEK/ERK and caveolin-1 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13879–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galdo FD, Sotgia F, de Almeida CJ, et al. Decreased expression of caveolin 1 in patients with systemic sclerosis: crucial role in the pathogenesis of tissue fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2854–65. doi: 10.1002/art.23791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang XM, Zhang Y, Kim HP, et al. Caveolin-1: a critical regulator of lung fibrosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2895–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Razani B, Zhang XL, Bitzer M, et al. Caveolin-1 regulates transforming growth factor (TGF)-β/Smad signaling through an interaction with TGF-β type I receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6727–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008340200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim S, Lee Y, Seo JE, et al. Caveolin-1 increases basal and TGF-β1-induced expression of type I procollagen through PI-3 kinase/Akt/mTOR pathway in human dermal fibroblasts. Cell signal. 2008;20:1313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tourkina E, Richard M, Gööz P, et al. Antifibrotic properties of caveolin-1 scaffolding domain in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L843–61. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00295.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drab M, Verkade P, Elger M, et al. Loss of caveolae, vascular dysfunction, and pulmonary defects in Caveolin-1 gene-disrupted mice. Science. 2001;293:2449–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1062688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le Lay S, Kurzchalia TV. Getting rid of caveolins: phenotypes of caveolin-deficient animals. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:322–33. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones JI, Clemmons DR. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocr Rev. 1995;16:3–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv-16-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Q, Li S, Zhao Y, et al. Evidence that IGF binding protein-5 functions as a ligand-independent transcriptional regulator in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2004;94:E46–54. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000124761.62846.DF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyakoshi N, Richman C, Kasukawa Y, et al. Evidence that IGF-binding protein-5 functions as a growth factor. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI10459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andress DL, Loop SM, Zapf J, et al. Carboxy-truncated insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5 stimulates mitogenesis in osteoblast-like cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;195:25–30. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajah R, Valentinis B, Cohen P. Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-3 induces apoptosis and mediates the effects of transforming growth factor β-1 on programmed cell death through a p53- and IGF-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12181–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.12181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schedlich LJ, Young TF, Firth SM, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (IGFBP)-3 and IGFBP-5 share a common nuclear transport pathway in T47D human breast carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18347–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.29.18347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schedlich LJ, Le Page SL, Firth SM, et al. Nuclear import of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 and -5 is mediated by the importin beta subunit. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23462–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002208200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andress DL. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 (IGFBP-5) stimulates phosphorylation of the IGFBP-5 receptor. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E744–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.4.E744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feghali CA, Wright T-M. Identification of multiple, differentially expressed messenger RNAs in dermal fibroblasts from patients with systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1451–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199907)42:7<1451::AID-ANR19>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilewski JM, Liu L, Henry AC, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins 3 and 5 are overexpressed in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and contribute to extracellular matrix deposition. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:399–407. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62263-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasuoka H, Zhou Z, Pilewski JM, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 induces pulmonary fibrosis and triggers mononuclear cellular infiltration. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1633–42. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yasuoka H, Hsu E, Ruiz XD, et al. The fibrotic phenotype induced by IGFBP-5 is regulated by MAPK activation and egr-1-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:605–15. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yasuoka H, Jukic DM, Zhou Z, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 induces skin fibrosis: a novel murine model for dermal fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3001–10. doi: 10.1002/art.22084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasuoka H, Yamaguchi Y, Feghali-Bostwick CA. The pro-fibrotic factor IGFBP-5 induces lung fibroblasts and mononuclear cell migration. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:179–88. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0211OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasuoka H, Larregina AT, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Human skin culture as an ex vivo model for assessing the fibrotic effects of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins. Open Rheumatol J. 2008;2:17–22. doi: 10.2174/1874312900802010017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim HP, Wang X, Galbiati F, et al. Caveolae compartmentalization of heme oxygenase-1 in endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2004;18:1080–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1391com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolz DB, Zamora R, Vodovotz Y, et al. Peroxisomal localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2002;36:81–93. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andrews NC, Faller DV. A rapid micropreparation technique for extraction of DNA-binding proteins from limiting numbers of mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:2499. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.9.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jurgeit A, Berlato C, Obrist P, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-5 enters vesicular structures but not the nucleus. Traffic. 2007;8:1815–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gashler A, Sukhatme VP. Early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1): prototype of a zinc-finger family of transcription factors. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;50:191–224. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60815-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okamoto T, Schlegel A, Scherer PE, et al. Caveolins, a family of scaffolding proteins for organizing “preassembled signaling complexes” at the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5419–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couet J, Li S, Okamoto T, et al. Identification of peptide and protein ligands for the caveolin-scaffolding domain. Implications for the interaction of caveolin with caveolae-associated proteins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6525–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee KW, Liu B, Ma L, et al. Cellular internalization of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3: distinct endocytic pathways facilitate re-uptake and nuclear localization. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:469–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carman CV, Lisanti MP, Benovic JL. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases by caveolin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8858–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hopkins CR, Trowbridge IS. Internalization and processing of transferrin and the transferrin receptor in human carcinoma A431 cells. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:508–21. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsia E, Richardson TP, Nugent MA. Nuclear localization of basic fibroblast growth factor is mediated by heparan sulfate proteoglycans through protein kinase C signaling. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:1214–25. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsieh T, Gordon RE, Clemmons DR, et al. Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell responses to insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I by local IGF binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42886–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303835200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koedam JA, Hoogerbrugge CM, Van Buul-Offers SC. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 and -5 form sodium dodecyl sulfate-stable multimers. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:707–14. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng Y, Venema VJ, Venema RC, et al. VEGF induces nuclear translocation of Flk-1/KDR, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and caveolin-1 in vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;256:192–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chrétien A, Piront N, Delaive E, et al. Increased abundance of cytoplasmic and nuclear caveolin 1 in human diploid fibroblasts in H(2)O(2)-induced premature senescence and interplay with p38alpha(MAPK) FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1685–92. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dittmann K, Mayer C, Kehlbach R, et al. Radiation-induced caveolin-1 associated EGFR internalization is linked with nuclear EGFR transport and activation of DNA-PK. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:69. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones JI, Gockerman A, WH Busby, Jr, et al. Extracellular matrix contains insulin-like growth factor binding protein-5: potentiation of the effects of IGF-I. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:679–87. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel HH, Zhang S, Murray F, et al. Increased smooth muscle cell expression of caveolin-1 and caveolae contribute to the pathophysiology of idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. FASEB J. 2007;21:2970–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8424com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]