Abstract

Motivation: Phenotypic information is important for the analysis of the molecular mechanisms underlying disease. A formal ontological representation of phenotypic information can help to identify, interpret and infer phenotypic traits based on experimental findings. The methods that are currently used to represent data and information about phenotypes fail to make the semantics of the phenotypic trait explicit and do not interoperate with ontologies of anatomy and other domains. Therefore, valuable resources for the analysis of phenotype studies remain unconnected and inaccessible to automated analysis and reasoning.

Results: We provide a framework to formalize phenotypic descriptions and make their semantics explicit. Based on this formalization, we provide the means to integrate phenotypic descriptions with ontologies of other domains, in particular anatomy and physiology. We demonstrate how our framework leads to the capability to represent disease phenotypes, perform powerful queries that were not possible before and infer additional knowledge.

Availability: http://bioonto.de/pmwiki.php/Main/PheneOntology

Contact: rh497@cam.ac.uk

1 INTRODUCTION

Large-scale genomics research increasingly includes the collection of phenotypic information to infer disease states from genetic conditions. Similarly, evolutionary studies heavily rely on phenotypic descriptions across species. Several biomedical databases collect and organize phenotypic information (Bult et al., 2008; Firth et al., 2009; The Flybase consortium, 1999). To integrate this information across different domains and databases and to communicate the data to the research community, phenotype ontologies were developed which formalize the meaning of terms used to characterize phenotypes (Gkoutos et al., 2004b; Robinson et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2004).

Ontologies are specifications of a conceptualization of a domain (Gruber, 1993) and are used to make the meaning of terms in a vocabulary explicit (Guarino, 1998) such that they can be used for consistency verification, information retrieval and knowledge discovery. At least two kinds of phenotype ontologies can be distinguished: ontologies in which each term contains one specific phenotypic trait (Robinson et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2004), and ontologies and methods that permit the composition of a term through the combination of an entity and a quality (Gkoutos et al., 2004a, b; Mungall et al., 2010). Each of these approaches describes a phenotype through qualities that are attributes of an entity. For example, a size of an arm would be described as a quality Size which is the quality of Arm.

In addition to these qualities, phenotype ontologies contain classes describing absence and presence of parts, functions, dispositions and processes, as well as abnormality. Currently, these features are also represented as qualities and rarely further analyzed. In particular, the attribution of qualities like Absent or Dysfunctional does not yet enable inferences about the parts or functions of an entity. Consequently, these approaches fail to interoperate with anatomy or physiology ontologies. If, however, the meaning of these qualities would be made explicit and classes like Absent or Dysfunctional characterized in terms of the has-part and has-function relations, information flow between phenotype and anatomy or physiology ontologies would be possible, thereby leading to a semantic integration of these ontologies and the capability for expressive queries.

As anatomy ontologies often represent canonical, prototypical organisms, inconsistencies may arise when they are combined with phenotype ontologies (Hoehndorf et al., 2007). For example, an anatomy ontology may contain a statement that asserts that every human has an appendix as part, while a phenotypic description of a human may assert that this human has no appendix as part. Because inconsistencies prevent query answering and semantic interoperability, a framework for phenotypic descriptions must accommodate statements about deviations from reference models without leading to inconsistencies.

We provide a method to make the intended meaning of phenotypic descriptions explicit and interoperable with anatomy and physiology ontologies. For this purpose, we first provide the means to formalize phenotypic traits while reusing classes and relations from other ontologies. Based on this formalization, we describe how to consistently integrate phenotypic descriptions with canonical ontologies and demonstrate how our method leads to expressive and flexible descriptions of disease phenotypes as well as the possibility for automated inference and knowledge discovery. We applied our method to examples taken from phenotype ontologies and provide an example ontology which is available from our project web site.

Our framework for formalizing phenotypic descriptions is based on the Web Ontology Language (OWL; Motik et al., 2009). OWL is based on an expressive, decidable fragment of first-order logic and provides the foundation for the Semantic Web. To maintain compatibility with currently established methods for representing phenotypes and reuse the data that has been annotated with it, we also demonstrate an implementation in the OBO Flatfile Format.

2 SYSTEMS AND METHODS

2.1 Overview

An organism is composed of organs, cells and other structural components. The variability of the structural components can be observed and described with the Entity–Quality (EQ) representation based on the Phenotypic Attribute and Trait Ontology (PATO; Gkoutos et al., 2004a; Mungall et al., 2010). Beyond the structure of organisms and its variability, we can observe processes in which the organism and its anatomical parts may participate. These processes may lead to changes in the structure or its variability in response to the organism's requirements. Developmental processes and functions such as growth and synaptic plasticity serve to change the organisms' structure and consequently lead to new dispositions. Furthermore, all living beings have to adapt to their environment and therefore expose responses in terms of changes to their structure and functioning. Structure and function form dual components (Hoehndorf et al., 2010a; Wright, 1973) in a system that describes the complexity of the phenotypes.

Many aspects of this complex network of interdependencies can currently be captured using biomedical ontologies. For example, the components and parts of organisms are described in anatomy ontologies such as the Foundational Model of Anatomy (FMA; Rosse and Mejino, 2003) or the cellular component branch of the Gene Ontology (GO; Ashburner et al., 2000). Organismal, cellular and molecular processes are described in the biological process branch of the GO, developmental anatomy ontologies are available for various species (Bult et al., 2008; Tweedie et al., 2009) and environmental features can be characterized with the Environment Ontology (Environment Ontology Consortium, 2008).

An ontological framework for phenotypes should enable the description of this variability and complexity, and interoperate with the existing ontologies and resources that were developed for it. In particular, a framework for representing phenotypes should enable the inference of consistent dependencies between different aspects in this network of dependencies, and provide for the detection of inconsistencies in the phenotypic description of an organism.

We first define a uniform framework for characterizing phenotypic properties of entities. For this purpose, we introduce the concept of phene that allows to make the semantics of an entity's features explicit and accessible to automated reasoning. As phenotypic characterizations are usually done comparatively with respect to the features of another reference entity, we show how to use the phene concept to facilitate interoperability of phenotypic descriptions with reference ontologies in biomedicine. In particular, we demonstrate how to formally represent and infer normality and abnormality. Based on the development of our formal framework for representing phenotypic information, we demonstrate how to apply it to knowledge discovery and querying across the diversity of knowledge resources containing phenotypic information.

2.2 Formalizing phenotypic traits

We define phene as a basic characteristics possessed by an organism. Phenes are attributive entities which are existentially dependent on a bearer, and phenes characterize the properties of their bearer. Therefore, we formally define phenes as the properties that are possessed by ‘entities which are Y’, and express Y as class-membership in description logic, or as a unary predicates in first-order logic. We call Y the defining property of a phene.

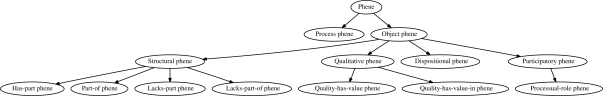

The defining property of a phene characterizes the phene's bearer, and therefore we can distinguish different kinds of phenes based on the relations that are necessary to formulate this characteristic. For example, a class of phenes, such as producing endorphines, refer to participation in processes of a certain kind. A large portion of phenes refer to ontological qualities: being cyanotic, being 7.5μm in size. Further phenes are structural, such as having or not having certain parts, refer to topology (being connected in a certain way) or to dispositions (being able to hear). To analyze and distinguish these differences, we derive a top-level classification of phenes based on the relations that are necessary to formulate their defining properties. Figure 1 gives an overview of this top-level classification.

Fig. 1.

The first distinction is drawn between phenes of objects and phenes of processes. We primarily classify phenes of objects into four main categories: structural, functional, qualitative and participatory phenes. Under the structural phenes, we show possible further classifications based on the relations we use in our method. Qualitative phenes can be further distinguished into those where only the quality is relevant and those where the quality's value is considered.

2.2.1 Structural phenes

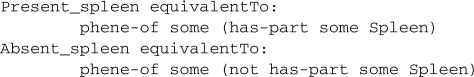

Structural phenes are based on the mereological relation part-of. The defining property of structural phenes is expressed using the part-of or has-part relation. Examples of structural phenes are present spleen and absent spleen which are defined as phenes of things which have (or do not have) a spleen as part:

The defining property is has-part some Spleen and not has-part some Spleen, and the instances of the defining property are entities that either have or do not have a spleen as part. Because our definition of these phenes uses the has-part relation, we can combine phenotypic information with anatomical information, thereby establishing an informative link between both.

2.2.2 Qualitative phenes

Another group of phenes represents ontological qualities and we call them qualitative phenes. Qualities are related to their bearer by the inheres-in relation and its inverse has-quality. We can express qualitative phenes using our definition pattern in a similar way as structural phenes: as phenes of things in which a certain quality inheres. For example, the phene being cyanotic is represented as a phene of things which have the quality (has-quality) cyanotic. We can further refine this by distinguishing qualities from their values and relate both used the value-of and has-value relations. Then, being cyanotic is represented as a phene of things that have a color within a certain value range.

2.2.3 Function and disposition phenes

Another group of phenes is related to functions and disposition of entities, and can be expressed using the has-function, function-of, has-disposition and disposition-of relations. We call these dispositional phenes. Intuitively, functions of biological entities establish the reason (or cause) that an entity exists (Wright, 1973) while their dispositions determine their capabilities and potentials (Lewis, 1997). For example, the endocrine pancreatic cells have a function to produce insulin, and normally have a disposition to produce insulin.

In many cases, neither functions nor dispositions are explicitly included in ontologies, but rather the processes that realize these functions or dispositions. Therefore, dispositional phenes will often be represented using the has-function-realized-by or has-disposition-realized-by design patterns (Hoehndorf et al., 2010a). Using these, a relation between a class C and a class of processes P is established such that every instance of C has a function (or disposition) that is only realized by processes of the kind P. For example, the endocrine pancreatic cells have a function to produce insulin which is realized through insulin production processes. The processes that result from the realizations of functions are called functionings (Johansson, 2004).

2.2.4 Functionings and processes

An organism or anatomical structure may participate in certain processes, for example in physiological, metabolic or developmental processes, or in the organism's activities. To participate in these processes is a participatory phene. Participatory phenes are represented with the participates-in and has-participant relations. Furthermore, we can distinguish different modes of participation for a phene of a process participant and thus determine how an entity participates in a process. We represent these phenes with the relation plays-processual-role (Loebe, 2005). For example, the sinoatrial nodes participate in blood pumping processes and play the processual role of an initiator of the rhythmic excitation of the heart muscle.

Apart from the phenes of process participants, we can distinguish a second kind of phene which represents characteristics of the processes themselves. We call this kind the process phenes, and they include characteristics of physiological processes, metabolic processes, biological pathways, chemical reactions and their parts. These processes can have attributes such as duration or a heart beat rate, they can have parts or participants. Although some aspects of our classification of phenes can also be applied to process phenes, we leave a detailed classification of process phenes as subject to future work.

2.2.5 The logic of phenes

Axioms for classes and relations: phenes are related to their bearers using the phene-of and has-phene relations. Because phenes are existentially dependent on their bearer, phenes are always the phene-of some entity. Furthermore, phene-of is functional, i.e. a phene belongs to at most one entity. Therefore, the following restriction holds for the class Phene:

![]()

The domain of the phene-of relation is the class Phene, while the range is owl:Thing, i.e. the class of all things. The relation has-phene is the inverse of the phene-of relation, i.e. whenever an individual x is the phene-of an individual y, then y stands in the has-phene relation to x. Because phene-of is functional, and has-phene is inverse functional.

Applying phenes to entities. a particular class of phenes P is defined with respect to a defining property Y of its bearers. Therefore, the definition pattern for phenes is

![]()

or

![]()

Because the phene-of relation is functional and the has-phene relation inverse functional, the following is true: if an individual i is the bearer of a phene of the kind P, i is an instance of Y.

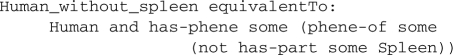

For example, we have defined the phene Absent spleen as the phene of things that have no Spleen as part. Based on this phene, we can define a class of Human without spleen as:

![]()

Based on the inference rules for OWL, we can show that this definition is equivalent to

and due to the functionality of phene-of and the inverse functionality of has-phene, this is equivalent to

![]()

Composing complex phenes: besides applying phenes to entities, we can introduce intersections and unions of phenes to form complex phenes. Due to the axioms for the phene-of and has-phene relations, intersections and unions of phenes correspond to intersections and unions of the defining properties of these phenes: when the class of phenes P1 is based on the defining property Y1, and P2 based on Y2, then the complex phene P1 and P2 is based on the defining property Y1 and Y2.

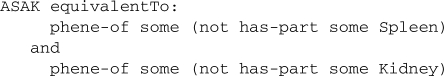

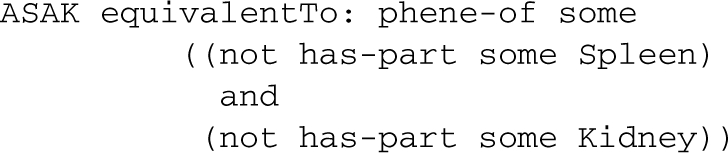

For example, in addition to the Absent spleen phene we define Absent kidney similar to Absent spleen. Then, we can define a complex phene Absent spleen and absent kidney (ASAK):

![]()

Through inference, we can show that this definition is equivalent to

and due to the functionality of the phene-of relation, this is equivalent to

The defining property of ASAK is not defined based on either of the relations in our ontology of phenes, and therefore it is not a primitive phene. However, through inference we can show that ASAK becomes a subclass both of Absent spleen and Absent kidney.

Reasoning with phenes: phenes can be used to infer additional knowledge and verify consistency. The simplest case is a contradictory application of phenes, e.g. an individual organism with both the Absent spleen and Present spleen phene. Due to the definition of both phenes, such an assertion would be inconsistent and can be automatically detected using automated inference.

More importantly, phenes can make use of the information in ontologies to infer that other phenes must hold as well. For example, when integrated with an anatomy ontology like the FMA, the phene Absent spleen entails the Absent serosa of spleen phene, because Serosa of spleen (FMA:15848) must be a part-of some Spleen according to the FMA. Similar entailments hold for relations between anatomical entities and their functions. For example, if endocrine pancreatic cells are the only cells with a function to secrete insulin, their absence can entail the absence of insulin secretion.

2.3 Phenes and comparative descriptions

Phenes are properties of entities and phenes whose defining property involves negation can be attributes of a large number of entities. Therefore, phenes alone should rarely be used to describe the set of phenotypic characteristics of an organism.

As phenotypic descriptions are often comparative statements with respect to a reference model, either a model of normality, a control group, another organism or similar, we can exploit these descriptions to record phenes that characterize deviations from such a reference model. In particular, we show how to integrate phenes with canonical ontologies, although other artifacts can serve as reference models as well.

2.3.1 Interoperability with canonical ontologies

Canonical ontologies are those that serve as reference models within their domain and characterize prototypical, idealized entities (Smith and Rosse, 2004). Phenotypic descriptions and representations should interoperate with such resources and use them to infer knowledge and verify consistency.

When phenes are combined with canonical ontologies, inconsistencies and unsatisfiable classes may arise (Hoehndorf et al., 2007). For example, the FMA states that every Human has a Spleen as part. Characterizing an instance of Human h with the Absent spleen phene will lead to an inconsistency: as an instance of Human, h must stand in the has-part relation to some instance of Spleen; because h has a phene of the Absent spleen type, h must not have an instance of Spleen as part.

For the purpose of integrating canonical ontologies and the phene method, we restructure canonical ontologies to explicitly state that they describe only canonical entities. For example, instead of stating that every human has a spleen as part, we restructure the corresponding anatomy ontology to state that every canonical human has some canonical spleen as part.

For phenotypic descriptions, we need to describe non-canonicity in a flexible way, and we have at least two choices: the non-canonicity of the spleen could either be the absence of a canonical spleen or the presence of a non-canonical spleen. The first choice is more general, as it allows both for the presence of a non-canonical spleen as well as for the absence of the spleen. Therefore, we adopt this option and define a non-canonicity of the spleen as a phene of things that have no canonical spleen as part. A non-canonicity is different from an absence of the spleen, which is a phene of things which have no spleen as part, whether canonical or not. An absence of the spleen automatically becomes a subcategory of a non-canonicity of the spleen according to this definition.

Formally, we introduce two new unary predicates called C and NC (for canonical and non-canonical, respectively). In description logics, both C and NC are classes. C and NC are disjoint and exhaustive, i.e. everything is either C or NC but not both. Based on these classes, we restructure canonical ontologies such that all occurrences of class symbols X are replaced with X and C. Biomedical ontologies consist to a large portion of statements of the kind X subClassOf: R some Y (Horrocks, 2007). Assertions of this kind are consequently replaced with X and C subClassOf: R some (Y and C). For example, the FMA statement that all Humans have a Spleen as part (Human subClassOf: has-part some Spleen) is replaced by ‘all canonical humans have a canonical spleen as part’ (Human and C subClassOf: has-part some (C and Spleen)). This replacement can be performed automatically using the OWLDEF method (Hoehndorf et al., 2010b).

Based on these definitions, we can formally define a non-canonicity of the spleen (NCOS):

![]()

Following our pattern, we can define a human with an NCOS as

![]()

from which we derive, using deductive reasoning in OWL, that an NCOSHuman has no canonical spleen as part. We can also prove that a NCOSHuman is a subclass of a non-canonical human, i.e. of Human and NC, because canonical humans must have a canonical spleen as part.

We demonstrate these features in an OWL ontology that formalizes abnormality and absence of the appendix, liver and β-cells. The demonstration ontology is available from our project website.

3 IMPLEMENTATION

A large portion of our method is based on description logic and the Web Ontology Language (OWL) (W3C OWL Working Group, 2009). Using OWL has the advantage that the myriad of software tools, methods and libraries that have been developed for the Semantic Web can be reused with the method. In particular, OWL has an explicit semantics that makes it amenable for automated reasoning. However, many biomedical ontologies are developed using the OBO Flatfile Format (Horrocks, 2007). For our method to be successful, we provide an implementation in the OBO Flatfile Format that is compatible with the description logic treatment of phenes and phenotypes put forward in this manuscript. For this purpose, we use the OWLDEF method (Hoehndorf et al., 2010b) to provide OWL definitions for relations in the OBO Flatfile Format. These relations follow our top-level ontology of phenes and are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of relations defined using the OWLDEF method

| Relation | OWLDEF | Example |

|---|---|---|

| CC-pheneOf-has-part | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-part some ?Y) | Having an appendix as part |

| CC-pheneOf-lacks-part | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some not (has-part some ?Y) | Not having an appendix as part |

| CC-pheneOf-part-of | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (part-of some ?Y) | Being part of an appendix |

| CC-pheneOf-not-part-of | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some not (part-of some ?Y) | Not being part of an appendix |

| CC-pheneOf-has-quality | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-quality some ?Y) | Having a color |

| CC-pheneOf-lacks-quality | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some not (has-quality some ?Y) | Not having a size |

| CC-pheneOf-has-quality-value-of | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-quality some (?Y and has-value some ?Z)) | Having color #4F1A33 (in RGB color space) |

| CC-pheneOf-lacks-quality-value-of | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-quality some (?Y and not (has-value some ?Z))) | Not having a mass of 0.12g |

| CC-pheneOf-has-quality-value-in | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-quality some (?Y and has-value-in some ?Z)) | Being between 1.2 and 1.7 m in height |

| CC-pheneOf-lacks-quality-value-in | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-quality some (?Y and not (has-value-in some ?Z))) | Not having between 13 and 18 gm/dl hemoglobin concentration |

| CC-pheneOf-has-disposition | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-disposition some ?Y) | Being able to hear |

| CC-pheneOf-lacks-disposition | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some not (has-disposition some ?Y) | Not being able to hear |

| CC-pheneOf-has-disposition-realized-by | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (has-disposition some (realized-by only ?Y)) | Being able to hear |

| CC-pheneOf-lacks-disposition-realized-by | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some not (has-disposition some (realized-by only ?Y)) | Not being able to hear |

| CC-pheneOf-plays-p-role | ?X subClassOf: Phene and pheneOf some (plays-p-role some ?Y) | Playing the role of catalyst within some process |

4 DISCUSSION

4.1 Towards canonical disease phenotypes

We envision one application of our method to provide a means for representing canonical disease states. For this purpose, we introduce the notion of canonical disease phenotype: a complex phene which is the combination of those phenes that constitute the idealized or canonical form of a disease. Some of the phenes in a disease phenotype are dispositional, while others relate to qualities, absence or presence of body parts and participation in physiological processes.

To characterize disease phenotypes further and utilize the existing ontologies for automated inferences and knowledge discovery, several domains have yet to be covered by canonical ontologies so that they can serve as a bridge that links existing resources. Table 2 provides an overview of available and missing resources and their relation to our method.

Table 2.

The table lists dependencies between different kinds of phenes, and resources which are necessary to formally represent them

| Type | Provides | Dependencies | Relevant | Missing | Example 1: | Example 2: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| resources | resources | Diabetes | Coagulation | |||

| Structural | Components composing the organism, both macroscopic and microscopic. Topology of structures. | Structures can be part of larger structures and are the result of developmental processes | FMA, GO-CC | Developmental anatomy (human) | β-cells in the pancreas | Liver cells |

| Quality | Attributes of the structures, observables pertaining to the variability of the structures | Qualities are existentially dependent on their bearers. | PATO, HPO, MPO | Qualities of anatomical entities | Reduced amount of β-cells in the pancreas | Liver cells are reduced and increased in size, increased fatty acid vacuoles |

| Functional and dispositional | Capabilities of the structures | Functions and dispositions are existentially dependent on a bearer | GO-MF | Anatomical functions | Function of β-cells to produce insulin | Function to produce coagulation factors |

| Process | Functionings of the structures, changes in the structures and the organism caused through functionings; physiology | Processes require structures as participants, and result from functionings of anatomical structures | GO-BP, FMA, functional systems | Physiology, metabolism | Import of glucose into muscle cells, reduction of lipid catabolism | Coagulation |

To infer and reason over developmental abnormalities, a developmental anatomy must be available. There are developmental anatomies for several model organisms (Segerdell et al., 2008; Tweedie et al., 2009). To describe human developmental defects, a human developmental anatomy ontology integrated with the FMA would be beneficial as reference model on which deviations can be based. Similarly, to describe missing, abnormal or additional dispositions and functions, a functional anatomy ontology should be developed. Although there are approaches to construct such a resource (Hoehndorf et al., 2010a; Johansson et al., 2005), no comprehensive ontological resource for anatomical functions has been developed so far. Similarly, almost no ontologies for canonical physiology are currently available.

To describe qualitative phenes such as those relating to color or size, qualitative descriptions can be added to anatomy ontologies. For this purpose, it is important to use ranges of values for qualities, because values for qualities are often highly variable. Using the phene method, it would further be beneficial to describe the qualities of the wild type or control group in genetic experiments. This has the additional benefit of providing additional documentation to an experiment. Such a documentation can increase the interoperability with ontologies of investigations such as the Ontology of Biomedical Investigations (OBI; Courtot et al., 2008).

The method we propose can be used to represent and infer dependencies between phenotypic traits and verify the consistency of descriptions of phenotypes. For example, the absence of liver cells entails that they cannot have qualities or functions, because both qualities and functions are dependent on a bearer. Consequently, physiological processes that rely on liver cells' functionings will be impaired. Similarly, the absence of insulin producing β cells will prevent them from exerting their function, leading to a disruption in glucose metabolism and consequently an increased concentration of glucose in the blood. Because phenes make the semantics behind phenotypic traits explicit, these interrelations can be asserted or inferred, depending on the information present in the corresponding canonical ontologies. In addition, if β cells are absent, they may not be increased in size or have dispositions, and making such an assertion would lead to an inconsistency that can be automatically detected.

Although the phene method intends to provide a semantic framework for representing phenotypic information, it can also be applied to other domains such as representing clinical information. In particular, canonical disease phenotypes are similar to canonical conceptual graphs which are used in the Canon Group's model to represent prototypical clinical findings (Friedman et al., 1995). Consequently, the phene method is currently being applied to represent the canonical disease phenotypes of primary immunodeficiency diseases in the PID Ontology (Adams et al., 2010).

4.2 Phenes and the EQ formalism

The phene method can provide a semantics for the Entity-Quality (EQ) formalism and make it amenable to automated reasoning. EQ is currently widely used to annotate and formalize phenotypes and phenotypic descriptions (Mungall et al., 2010), and its formalization states that an EQ statement is equivalent to a Quality (Q) that inheres-in an Entity (E) (Mungall, 2007). This approach is strictly weaker than our method and corresponds to the use of the relation CC-pheneOf-has-quality (Table 1) in our method.

The currently employed semantics for EQ has several shortcomings. First, it is based on the assumption that phenotypic characters are qualities. Qualities do not allow to infer further information about other kinds of entities such as parts, functions and processes, and therefore the EQ semantics limits interoperability with other ontologies. For example, having a quality Lacks all parts of type (PATO:0002000) or Lacks function of type (PATO:0001641) formally conveys no information about the parts or functions of an entity. Even more problematic is the use of the towards relation to specify the kind of entity that is absent: in its currently used semantics (Horrocks, 2007), Absent spleen is interpreted as a Lacks all parts of type quality that is directed towards some Spleen. In this statement, towards is used in an existential restriction over Spleen, thereby leading to the inference that an instance of Spleen must exist in order to be absent.

The second shortcoming of EQ relates to the combination of qualities, which is important to describe complex phenotypic characteristics or disease phenotypes. In EQ, qualities from PATO are characteristics such as color or length, and intersections of color and length would be qualities which are both a color and a length at the same time. Such qualities do not exist in the domain of phenotypes. However, combined qualities such as Absent spleen and absent kidney are intended to be the qualities of organisms that have both an absent spleen and an absent kidney.

The method we propose overcomes these shortcomings by explicitly defining phenotypic characteristics using relations and classes from other ontologies. In addition, we demonstrated how phenes can be combined through intersections to form complex phenes.

4.3 Normality and abnormality

Being normal and being canonical are sometimes used synonymously, but we make a distinction between both because canonicity does not always coincide with normality. For example, although the canonical human body represented by the FMA is both male and female (in virtue of having both ovaries and testes as part), normal humans are either male or female, but not both. Being both male and female would instead be considered to be abnormal. Additionally, in experiments, normal is defined with respect to a control group of organisms, and not directly based on a canonical ontologies. Also, normal affects all phenes, while canonicity is often restricted to structure, function and physiology. Consequently, a tail size of a mouse may be within a certain normal range within a population of mice, abnormal within another population, and not considered in a canonical ontology at all. The reason is that normal and abnormal are statistical, empirical measures, while canonical and non-canonical are based on prototypical idealizations constructed by humans.

Our method is neutral with respect to these distinctions. We could introduce another set of predicates, Normal and Abnormal, both of which are neither a sub- nor a super-class of C and NC. Being Normal would, for example, entail being either male or female, but not both. In an ontology of Normal humans, sex would either not be considered (when the ontology is open or incomplete in this aspect), or two kinds of humans would be distinguished based on their sex.

An important application is the specification of Normal phenes of organisms within the context of an experiment. These phenes can include qualities such as fur color, tail size or similar, i.e. the phenes that are measured within an experiment protocol. Then, an organism or anatomical part of the organism is Abnormal if it lies outside the range of values that is considered normal. As for canonical and non-canonical entities, a phene P is an abnormality with respect to the Normal phene Q if having the phene P implies not having Q.

4.4 Future research

To integrate phenotype and canonical ontologies, we rely on introducing explicit classes for canonicity and non-canonicity. This permits a consistent integration of these ontologies, but has some drawbacks. In particular, when an organism has a single deviation from its canonical form, the organism is non-canonical and inferences from assertions in canonical ontologies cannot be drawn anymore. To prevent this issue, more distinctions than canonical versus non-canonical can be introduced (Rector, 2004). In the future, we plan to integrate our method of representing phenotypes in a framework that supports default reasoning (Hoehndorf et al., 2007).

4.5 Conclusions

We developed a method to represent phenotypic information in ontologies such that the semantics is made explicit. For this purpose, we introduce a category of phenes. Phenes are basic observable features of organisms which are defined with respect to a defining property. Defining properties can include absence or presence of parts or functions. This defining property is the feature of phenes that allows to make their semantics explicit and facilitate information flow with other ontologies based on the use of common relations.

Using our method to represent phenotypic information, we suggest a new top-level classification of phenotypic characteristics, based on the relations used in the defining properties of the phenes. The main distinction is between phenes of processes and phenes of objects. Those of objects are further distinguished into structural, qualitative, functional and participatory phenes. The first kind pertain to presence or absence of parts, the second to having qualities or values of qualities within certain ranges. Functional phenes characterize the functionality or dysfunctionality of organisms or their parts. Participatory phenes characterize the participation and the mode of participation of organisms and their parts in processes.

The formal representation of phenotypic information permits the integration of canonical ontologies with phenotype ontologies. For this purpose, canonical ontologies must be re-interpreted as explicitly referring to canonical entities, while phenotype ontologies can refer to either the canonical, the non-canonical or both kinds of entities. This simple restructuring, which can be hidden from ontology users, together with our proposed method enables the representation of canonical disease phenotypes as a means for characterizing disease states.

Altogether, we provide an explicit and formal framework for representing phenotypes that is applicable within biomedical ontologies for reasoning, answering queries and integrating knowledge about domains ranging from molecular biology to medicine. This enables the use of knowledge-based methods to infer, structure, classify and query information about disease and phenotype, thereby facilitating translational research and medicine.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Nico Adams and George Gkoutos for valuable discussions about phenotypes and their representations.

Funding: This research was funded by the European Bioinformatics Institute.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Adams N, et al. The ontology of primary immunodeficiency diseases (PIDs): using PIDs to rethink the ontology of phenotypes. In: Herre H, et al., editors. Proceedings of “Ontologies in Biomedicine and Life Sciences”. Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Epidemiology (IMISE), University of Leipzig; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bult CJ, et al. The mouse genome database (MGD): mouse biology and model systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D724–D728. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtot M, et al. Dolbear C, et al., editors. The OWL of biomedical investigations. Proceedings of the Fifth OWLED Workshop on OWL: Experiences and Directions. 2008;432 of CEUR Workshop Proceedings. Availabe at http://sunsite.informatik.rwth-aachen.de/Publications/CEUR-WS/Vol-432/ (last accessed date October 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Environment Ontology Consortium. Environment Ontology (EnvO). 2008 Available at: http://www.obofoundry.org/cgi-bin/detail.cgi?id=envo (last accessed date October 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Firth HV, et al. Decipher: database of chromosomal imbalance and phenotype in humans using ensembl resources. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009;84:524–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Flybase consortium. The FlyBase database of the Drosophila genome projects and community literature. The FlyBase Consortium. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:85–88. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman C, et al. The canon group's effort: working toward a merged model. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 1995;2:4–18. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1995.95202547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkoutos GV, et al. Building mouse phenotype ontologies. Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 2004a:178–189. doi: 10.1142/9789812704856_0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkoutos GV, et al. Using ontologies to describe mouse phenotypes. Genome Biol. 2004b doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber TR. Towards principles for the design of ontologies used for knowledge sharing. In: Guarino N, Poli R, editors. Formal Ontology in Conceptual Analysis and Knowledge Representation. Deventer, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino N. Formal ontology and information systems. In: Guarino N, editor. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Formal Ontologies in Information Systems. IOS Press; 1998. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hoehndorf R, et al. Representing default knowledge in biomedical ontologies: application to the integration of anatomy and phenotype ontologies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:377. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehndorf R, et al. Applying the functional abnormality ontology pattern to anatomical functions. J. Biomed. Semantics. 2010a;1:4. doi: 10.1186/2041-1480-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehndorf R, et al. Relations as patterns: Bridging the gap between OBO and OWL. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010b;11:441+. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks I. OBO flat file format syntax and semantics and mapping to OWL Web Ontology Language. Technical report, University of Manchester; 2007. Available at: http://www.cs.man.ac.uk/~horrocks/obo/ (last accessed date October 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I. Functions, function concepts, and scales. Monist. 2004;87:96–114. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson I, et al. Functional anatomy: a taxonomic proposal. Acta Biotheor. 2005;53:153–166. doi: 10.1007/s10441-005-2525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. Finkish dispositions. Philos. Q. 1997;47:143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Loebe F. Abstract vs. social roles: A refined top-level ontological analysis. In: Boella G, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 2005 AAAI Fall Symposium ‘Roles, an Interdisciplinary Perspective: Ontologies, Languages, and Multiagent Systems’. Menlo Park, CA, USA: AAAI Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Motik B, et al. OWL 2 web ontology language structural specification and functional-style syntax. Technical report. 2009:W3C. [Google Scholar]

- Mungall C. Representing phenotypes in OWL. In: Golbreich C, et al., editors. Proceedings of the OWLED 2007 Workshop on OWL: Experiences and Directions. 2007. Available at http://sunsite.informatik.rwth-aachen.de/Publications/CEUR-WS/Vol-258/ (last accessed date October 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Mungall C, et al. Integrating phenotype ontologies across multiple species. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R2+. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-1-r2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rector AL. Defaults, context, and knowledge: Alternatives for OWL-indexed knowledge bases. In: Altman RB, et al., editors. Proceedings of the 9th Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing (PSB 2004), Hawaii, USA, Jan 6-10. London: World Scientific; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PN, et al. The human phenotype ontology: a tool for annotating and analyzing human hereditary disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;83:610–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosse C, Mejino JLV. A reference ontology for biomedical informatics: the Foundational Model of Anatomy. J. Biomed. Inform. 2003;36:478–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerdell E, et al. An ontology for xenopus anatomy and development. BMC Dev. Biol. 2008;8:92. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B, Rosse C. The role of foundational relations in the alignment of biomedical ontologies. Medinfo. 2004;11:444–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, et al. The mammalian phenotype ontology as a tool for annotating, analyzing and comparing phenotypic information. Genome Biol. 2004;6:R7. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tweedie S, et al. Flybase: enhancing drosophila gene ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Suppl. 1):D555–D559. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- W3C OWL Working Group. Technical report. Cambridge, MA, USA: 2009. OWL 2 Web Ontology Language: Document overview. W3C, Available at: http://www.w3.org/TR/owl2-overview/ (last accessed date October 29, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Wright L. Functions. Philos. Rev. 1973;82:139–168. [Google Scholar]