Abstract

Summary: GLay provides Cytoscape users an assorted collection of versatile community structure algorithms and graph layout functions for network clustering and structured visualization. High performance is achieved by dynamically linking highly optimized C functions to the Cytoscape JAVA program, which makes GLay especially suitable for decomposition, display and exploratory analysis of large biological networks.

Availability: http://brainarray.mbni.med.umich.edu/glay/

Contact: sugang@umich.edu

1 INTRODUCTION

With the rapid development in experimental and computational technology, the scale and dimension of accumulated molecular interaction data have increased dramatically. Many online repositories, such as Michigan molecular interaction (MiMI; Tarcea et al., 2009), have made extensive gene-wise interaction data readily available. The challenge is then how to systematically explore and visualize such large and complex datasets for biological inferences. One solution is to decompose such an interaction network into communities of densely interacting nodes and imply functional modules. A variety of community detection algorithms have been developed to tackle similar challenges in social networks and they have been successfully extended to the biological context (Schwarz et al., 2008; Viana et al., 2009). Recently, Ruan et al. (2010) proposed an interesting generic method combing association networks with community structure detection algorithms to infer network modules from microarray data.

Cytoscape is a well-established open source software foundation for analysis and visualization of biological networks. Currently there are several plugins developed for clustering and functional module detection, such as MCode (Bader and Hogue, 2003), NeMo (Rivera et al., 2010) and ClusterMaker (http://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/cytoscape/cluster/clusterMaker.html). However, some algorithms in ClusterMaker, such as kmeans or hierarchical, require the network to have numerical attributes to compute a distance matrix for clustering. MCode and NeMo are engineered to identify small and highly intra-connected clusters in a network, without clustering all the nodes. For example, when executed on a MiMI human interactome network of 11 884 nodes and 88 134 edges using the default parameters, MCODE produced 105 clusters, in which 52 clusters contain less than five nodes. Therefore, it may not be suitable for global subdividing large networks for exploratory analysis. In addition, some of these plugins were not tailored for large networks. For example, NeMo failed when executing on the same MiMI network on a 2.67 GHz Intel Core i7 machine. So far, no plugin offers a comprehensive collection of highly efficient community detection algorithms, which could profoundly improve cluster analysis if added to Cytoscape.

The increasing size and complexity of networks also bring significant challenges to visualization. Generating a layout on such a network not only consumes considerable time and computational resources, but also rarely produces any informative outcome. A typical case is a massive hairball as a result of applying force-based layout to a large network (> 500 nodes) with many edges (Merico et al., 2009). Visual separation of clusters in a network can be improved by overlaying community structure on a graphic layout addressing specific topology.

We therefore developed this Cytoscape GLay plugin to make commonly used community structure detection algorithms available. GLay also provides layout algorithms optimized for large networks. GLay not only supplements existing clustering functions, but also provides structured and informative visualization for more efficient exploration and analysis of large biological networks.

2 IMPLEMENTATION

The core of GLay was developed as a Cytoscape plugin with high-performance community analysis and graph layout functions ported from igraph C library (Csardi and Nepusz, 2006). The bridging is built via Java native access (JNA, https://jna.dev.java.net) interface. The functions ported from igraph C library are currently only compiled under Windows 32/64 bit platform but will be extended to other platforms in the near future.

Before performing any community analysis, GLay automatically transforms the input network into a simplified model, with edge directionality, duplication and self-looping removed. Such a network standardization step will make the resultant community structures from different community structure detection algorithms comparable as well as improving performance. Upon completion of an analysis, the user may browse the resultant community structure with the built-in GLay navigator panel.

Table 1 summarizes the incorporated community detection algorithms. Because of the distinct heuristics of algorithms, running speed and the resultant community structures vary. Some algorithms, such as the leading eigenvector algorithm, works well on a small network of a few hundred nodes but may not be scalable for large networks. Others are optimized for large datasets but may be less accurate. For example, the fast greedy algorithm may produce communities with skewed community size distribution because of the greedy optimization of the modularity score (Wakita and Tsurumi, 2007). Users may test different algorithms and evaluate performance by various benchmarks such as modularity, number of communities and community size distribution.

Table 1.

GLay community algorithms

| Connected components | Find connected clusters from a network |

|---|---|

| Edge betweenness (Newman and Girvan, 2004) | Optimization of modularity score utilizing edge betweenness score |

| Fast-greedy (Original, HE, HN, HEN) (Clauset et al., 2004; Wakita and Tsurumi, 2007) | Greedy optimization of modularity score, with different corrections on edge density and cluster size |

| Label propagation (Raghavan et al., 2007) | Determine community membership by iterative neighbor votes |

| Leading eigenvector (Newman, 2006) | Find communities using eigenvector of matrices |

| Spin glass (Global, Single) (Reichardt and Bornholdt, 2006) | Using spin glass model and simulated annealing. The single mode allows finding communities only surrounding selected nodes |

| Walk trap (Pons and Latapy, 2005) | Determine community membership via short random walks |

Table 2 lists GLay layout algorithms. These algorithms are able to efficiently layout very large networks or generate hierarchical trees. A key advantage of GLay layout is that it allows the layout calculations of various algorithms to initiate from the current network layout state. This adds significant flexibility since it enables the user to progressively improve the layout by either fine-tuning parameters or using different layout algorithms together. For example, for a very large network, the user may specify a small number of iterations to obtain a draft layout, and then gradually refine the layout by adding more iterations or tuning the parameters. Once done, the user may superimpose the community structure on the layout to investigate network topology. For more information, please refer to the plugin homepage and igraph library documentation (Csardi and Nepusz, 2006).

Table 2.

GLay layout algorithms

| Fruchterman Reingold (original, grid) (Fruchterman and Reingold, 1991) | Efficient force-based algorithms, with the grid version optimized for large networks |

| graphopt (GraphOPT http://www.schmuhl.org/graphopt/) | Force-based algorithm with optimization |

| Kamada kawai | Force-based spring layout |

| Large graph layout (Adai et al., 2004) | Large graph layout algorithms for connected graphs |

| Multidimensional scaling (MDS) (Brandes and Pich, 2007) | Layout based on multidimensional scaling based on shortest distances |

| reingold tilford (hierarchical, circular) (Reingold and Tilford, 1981) | Tree-like layout for connected networks, can be hierarchical or circular from any node as root |

3 RESULTS AND CONCLUSION

We have tested GLay on datasets of various size and structure. GLay demonstrated substantial performance gain in both network decomposition and layout over existing Cytoscape solutions. For example, using GLay to subdivide the MiMI human Interactome—which contains 11 884 nodes and 88 134 edges—takes 0.7 s using the label propagation algorithm and 20 s using the fast greedy algorithm on the same 2.67 GHz Intel Core i7 machine. MCODE takes 198 s to find clusters. Generating layout on this network using the Fruchterman Reingold grid algorithm takes about 20 s, whereas the Cytoscape built-in force directed and spring embedded algorithms both reported error during execution both with default setup and 1.5 G heap space. This demonstrates that Java-C hybrid model has dramatic performance advantage handling large networks in Cytoscape.

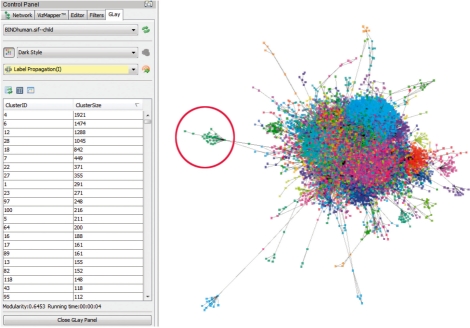

GLay also enables easy navigation of clustering results. Figure 1 shows a screenshot of overlaying fast greedy community structure on Fruchterman Reingold grid layout on the Cytoscape built-in BIND human dataset. Users may navigate and explore communities of genes with the GLay browser. For example, clicking the cluster entry in the browser table will select all nodes within a cluster. The user will then be able to create a new subnetwork or nested network from the selected nodes, extract gene lists from attribute browser or incorporate other experimental data for various research interests.

Fig. 1.

Fast-greedy community structure superimposed on Frutcherman Reingold grid layout from the largest component of Cytoscape human BIND dataset, consists of 17 961 nodes and 30 156 edges. Note that nodes belong to the same community tend to aggregate spatially, which resulted in clusters with good visual separation. The red circle indicates a group of highly interacting immunoglobulins.

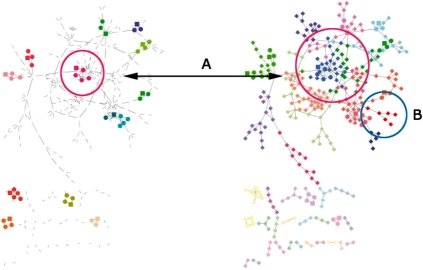

In addition, GLay can provide qualitative different results from existing solutions. Figure 2 shows a side-by-side comparison of MCODE at default parameters and GLay using fast greedy algorithm. It can be seen that by using the default parameters, MCODE produces much smaller clusters than GLay, leaving majority of the nodes unclustered. Therefore, GLay outperforms MCODE in terms of structural partitioning of the original network. In addition, overall GLay has higher sensitivity than MCODE at the trade-off of specificity, which made it more suitable for functional interpretation. For example, in Figure 2, one cluster in MCODE contains five genes, with four genes function in MAPK pathway. The equivalent GLay cluster contains 25 genes. Submitting these genes to DAVID (Dennis et al., 2003) reveals one enriched functional cluster for the MCODE cluster and nine enriched functional cluster for the GLay cluster. As some of the genes such as cdc28 and ste12 are involved in multiple regulation processes, the GLay cluster recovered more biological-relevant information than the equivalent MCODE cluster.

Fig. 2.

Comparison between clusters produced by MCODE with default parameters (left) and GLay using fast-greedy algorithm (right) on Cytoscape bundled galFiltered (Ideker et al., 2001) dataset. The node color is determined by the corresponding cluster membership. Left: MCODE clusters. The un-clustered genes are hidden. Right: GLay fast-greedy clusters. (A) A MCODE cluster, in which four out of five genes are associated with MAPK pathway. The corresponding cluster in GLay contains 25 genes, including more genes in MAPK pathway, cell cycle and ion binding. (B) A GLay cluster not identifiable by MCODE. This cluster consists of six genes, with four are related to RNA process.

In summary, GLay capitalizes on the power of highly optimized C code from several social network analysis and network layout algorithms to improve scalability of Cytoscape for large networks. We hope GLay can help to address the increasing needs for analysis and visualization of large-scale networks. We are committed to add cross-platform support for Linux and Mac environments as well as to integrate novel network analysis and layout functions in GLay.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the igraph developers Gabor Csardi and Tamas Nepusz, and the JNA community for enormous help during the development. We also thank Jing Gao for providing Interactome data from MiMI and user testing. We appreciate the Google Summer of Code which provided great opportunity for the initial phase of this project, Samad Lotia from Agilent Technologies for helping with building the plugin on Linux platform, and Josh Bucker for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by National Center for Integrated Biomedical Informatics through National Institutes of Health (grant 1U54DA021519-01A1 to the University of Michigan), also partly supported by a NIH NCRR grant P41-RR01081 to the University of California, San Francisco.

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Adai AT, et al. LGL: creating a map of protein function with an algorithm for visualizing very large biological networks. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;340:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes U, Pich C. Eigensolver methods for progressive multidimensional scaling of large data. Graph Draw.g. 2007;4372:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Clauset A, et al. Finding community structure in very large networks. Phys. Rev. E. 2004;70:066111. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.066111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csardi G, Nepusz T. The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal. 2006;1695 Available at http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/igraph/citation.html. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis GJr, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruchterman TMJ, Reingold EM. Graph drawing by force-directed placement. Softw. Pract. Exp. 1991;21:1129–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Ideker T, et al. Integrated genomic and proteomic analyses of a systematically perturbed metabolic network. Science. 2001;292:929–934. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5518.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merico D, et al. How to visually interpret biological data using networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2009;27:921–924. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MEJ. Finding community structure in networks using the eigenvectors of matrices. Phys. Rev. E. 2006;74:036104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.036104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MEJ, Girvan M. Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Phys Rev E. 2004;69:026113. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.026113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pons P, Latapy M. Computing communities in large networks using random walks. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2005;3733:284–293. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan UN, et al. Near linear time algorithm to detect community structures in large-scale networks. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft. Matter Phys. 2007;76:036106. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.036106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt J, Bornholdt S. Statistical mechanics of community detection. Phys. Rev. E. 2006;74:016110. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.016110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reingold EM, Tilford JS. Tidier drawings of trees. IEEE T Softw. Eng. 1981;7:223–228. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera CG, et al. NeMo: network module identification in Cytoscape. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11(Suppl. 1):S61. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S1-S61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan J, et al. A general co-expression network-based approach to gene expression analysis: comparison and applications. BMC Syst. Biol. 2010;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz AJ, et al. Community structure and modularity in networks of correlated brain activity. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2008;26:914–920. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2008.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarcea VG, et al. Michigan molecular interactions r2: from interacting proteins to pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D642–D646. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana MP, et al. Modularity and robustness of bone networks. Mol. Biosyst. 2009;5:255–261. doi: 10.1039/b814188f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakita K, Tsurumi T. Proceedings of IADIS International Conference on WWW/Internet 2007. Banff, Alberta, Canada: 2007. Finding community structure in a mega-scale social networking service; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar]