Abstract

Bufalin, a naturally occurring small-molecule compound from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Chansu showed inhibitory effects against human prostate, hepatocellular, endometrial and ovarian cancer cells, and leukemia cells. However, whether or not bufalin has inhibitory activity against the proliferation of human non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells is unclear. The aim of this study is to study the effects of bufalin on the proliferation of NSCLC and its molecular mechanisms of action. The cancer cell proliferation was measured by MTT assay. The apoptosis and cell cycle distribution were analyzed by flow cytometry. The protein expressions and phosphorylation in the cancer cells were detected by Western blot analysis. In the present study, we have demonstrated that bufalin suppressed the proliferation of human NSCLC A549 cell line in time- and dose-dependent manners. Bufalin induced the apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by affecting the protein expressions of Bcl-2/Bax, cytochrome c, caspase-3, PARP, p53, p21WAF1, cyclinD1, and COX-2 in A549 cells. In addition, bufalin reduced the protein levels of receptor expressions and/or phosphorylation of VEGFR1, VEGFR2, EGFR and/or c-Met in A549 cells. Furthermore, bufalin inhibited the protein expressions and phosphorylation of Akt, NF-κB, p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2) and p38 MAPK in A549 cells. Our results suggest that bufalin inhibits the human lung cancer cell proliferation via VEGFR1/VEGFR2/EGFR/c-Met–Akt/p44/42/p38-NF-κB signaling pathways; bufalin may have a wide therapeutic and/or adjuvant therapeutic application in the treatment of human NSCLC.

Keywords: Bufalin, Non–small cell lung cancer, Proliferation, Apoptosis, Cell cycle arrest, VEGFR/EGFR/c-Met, MAPKs, Akt-NF-κB pathways

Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among both men and women in the world (Jemal et al. 2008; Parkin et al. 2005). Despite recent advances in diagnosis and treatment, overall 5-year survival of lung cancer patients is only 15%. The non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which constitutes ~80% of lung cancer cases, remains an aggressive lung cancer associated with a poor patient survival. The patients with advanced disease have a median survival of approximately 10 months when treated with standard platinum-based therapy. Tumors depend on complex signaling networks to promote malignant progress and dynamically adapt to stress including chemotherapy drug treatment. Blocking only one of these pathways allows others to act as salvage or escape mechanisms for cancer cells. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new anticancer agents that could produce the most effective targeted cancer therapies by their concomitant inhibition of multiple targets. Bufalin is a naturally occurring small-molecule compound from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Chansu which has been used to treat lung, hepatocellular carcinoma, or pancreatic cancer in human patients (Meng et al. 2009). Chansu is the dried venom of toad (Bufo bufo gargarizans CANTOR or Bufo melanostictus SCHNEIDER) and has been used as an Oriental drug (Yasuharu et al. 2004). The chemical structure of bufalin is shown in Fig. 1. Bufalin isolated from Chansu was reported to have the activity of inducing apoptosis in cancer cells such as human prostate, hepatocellular, endometrial and ovarian cancer cells and leukemia cells. (Gu et al. 2007; Takai et al. 2008; Watabe et al. 1996; Yu et al. 2008). However, whether or not bufalin has inhibitory activity against the proliferation of human NSCLC cells and its molecular mechanisms of action are unclear. In the present study, we show that bufalin significantly inhibited the proliferation of human NSCLC A549 cell line by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. We have demonstrated that the molecular mechanisms of action of bufalin against the cancer cells are associated with suppressing the related receptors-mediated multiple signaling pathways in the cancer cells.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of bufalin (BF)

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

The primary antibodies to human Bcl-2, Bax, pp38 and p38 MAP kinase, pp44/42 and p44/42 MAPK (ERK1/2), p21 Waf1/Cip1, p53, caspase-3, PARP-1, cytochrome c, cyclic D1, and β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Beverley, MA, USA). The primary antibodies to human pVEGFR2, VEGFR2, VEGFR1, pEGF, EGF, p-c-Met, c-Met, nuclear factor (NF-κB p-65), p-NF-κB, Akt, and pAkt were purchased from Santa Cruz Technology Inc. (Beverley, MA, USA). DMEM, Penicillin, streptomycin, fetal bovine serum (FBS), trypsin/EDTA, propidium iodide, gelatin, 3-[4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), bufalin, Ly294002 (LY), Bay 11-7082 (Bay), SB203580 (SB), and PD98059 (PD) and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture and in vitro proliferation assay

The A549 lung adenocarcinoma cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The human cancer cell lines A549 was cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (100 U/mL) and streptomycin (100 μg/mL) at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere. The in vitro assay was performed according to our published methods (Liu et al. 2009; Luan et al. 2010). Cells were plated in 96-well plates (Becton–Dickinson, NJ, USA) at 2 × 103 per well and incubated overnight to allow attachment. The cells in control group were treated with DMSO [0.1% (v/v), final concentration]. The cells were, respectively incubated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS containing different concentrations of bufalin (BF, 2.5–10 μM), Ly294002 (LY, 50 μM), Bay (10 μM), PD98059 (PD, 7 μM), and SB203580 (SB, 50 μM). LY, Bay, PD, and SB are the inhibitors of PI3 K/Akt, NF-κB, p44 (ERK1/2), and p38 MAPK, respectively. After 48 or 72 h of treatment, 20 μL of MTT (5 mg/mL) was added to each well of cells, and the plate was incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. One hundred and fifty microliters DMSO were added to each well to lyse the cells. Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm and a reference wavelength of 630 nm using a Synergy H4 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek, Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Absorbance values in each test group were normalized to the values of the control group treated with 0.1% (v/v) DMSO to determine the viability (%) of A549 cells. Here the absorbance values are designated as the viability rate (%) of A549 cells. The viability rate of A549 cells in the control group was designated as 100%. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated at least 3 times.

Flow cytometry for cell cycle analysis and apoptosis

These were done according to our published methods (Wang et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2000). In brief, A549 cells were treated for 48 h with bufalin at concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM. The treated cells were detached in PBS/2 mM EDTA, centrifuged at 300 × g for 5 min, and then gently resuspended in 250 μL of hypotonic fluorochrome solution (PBS, 50 μg propidium iodide, 0.1% sodium citrate, and 0.1% Triton X-100) with RNase A (100 units/mL). The function of the fluorochrome solution is to stain cell nuclei. The DNA content was analyzed by flow cytometry (Becton–Dickinson FACS Vantage SE, San Jose, CA, USA). Twenty-thousand events were analyzed per sample and the cell cycle distribution and apoptosis were determined based on DNA content and the Sub-G1 cell population, respectively.

Western blot analysis

This was performed according to our published methods with some modifications (Wang et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2009; Zhang et al. 2009). In brief, A549 cells were treated with bufalin (0, 2.5, 5 and 10 μM), or Ly294002 (LY, 50 μM), Bay (10 μM), PD98059 (PD, 7 μM), and SB203580 (SB, 50 μM). The cells in control group were treated with DMSO [0.1% (v/v), final concentration]. The treated cells were collected either at 30 min for detection of phosphorylation ratios of pVEGFR2/pVEGFR2, pEGFR/EGFR, p-c-Met/c-Met, pAkt/Akt, pp38/p38, pp44/42/p44/42, and pNF-κB/NF-κB, or at 48 h for detection of protein expressions of Bcl-2, Bax, p21WAF1, p53, procaspase/caspase-3, PARP-1, cyclin D1, VEGFR1, COX-2, and cytochrome c. For detection of mitochondrial and cytosolic cytochrome c, both mitochondrial and cytosolic proteins from the cell extracts were used. The method of mitochondrial purification was described below. Equal amounts of cell extracts were resolved by SDS–PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and probed with the primary antibodies to the proteins to be detected as mentioned above, and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, respectively. Anti-β-actin antibody was used as a loading control. Detection was done using an enhanced chemiluminescence system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Piscataway, NJ USA).

Mitochondrial purification

A549 cells were seeded in a 10 cm dish. The cells were treated for 48 h with BF (BF1/2.5, BF5/5, BF10/10 μM), Bay (10 μM), and Ly (50 μM). After the treatment, the cells were harvested and lysed in homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.7, 10 mM KCl, 0.15 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM DTT). After incubating on ice for 15 min, cell membranes were disrupted by more than 10 passes through a 23-gauge needle. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 7,000 × g for 10 min. The mitochondrial pellet obtained was resuspended in mitochondrial suspension buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.7, 0.15 mM MgCl2, 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT). The supernatant was spun at 9,500 × g for 5 min to re-pellet the mitochondria. Protein concentrations were determined by Bio-Rad protein assay and equivalent amounts of protein were resolved by SDS–PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. After the membrane was blocked in Tris-buffer saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) and 5% non-fat powdered milk, the membranes were incubated with primary antibody specific to cytochrome c.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) and analyzed by the SPSS 13.0 software to evaluate the statistical difference. Statistical analysis was done using the ANOVA and Bonferroni test. Values between different treatment groups at different times were compared. The rate (%) of cell viability and mean protein levels are shown for each group. For all tests, p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results and discussion

Bufalin shows in vitro inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in A549 cells

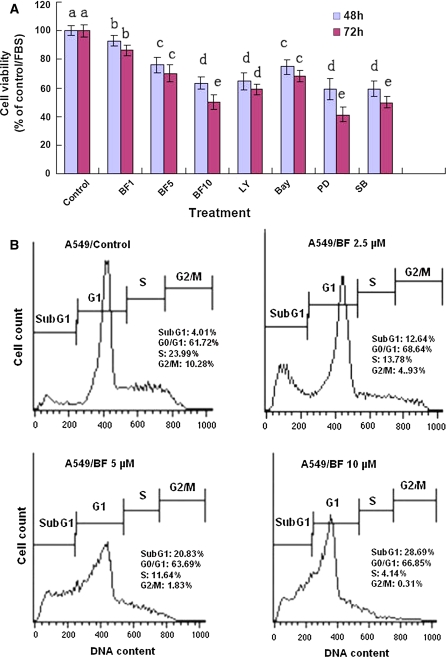

We first confirmed that bufalin reduced the viability rates of human NSCLC A549 cell line in dose- and time-dependent manners after the cells were treated with bufalin at 2.5–10 μM for 48 and 72 h, respectively (Fig. 2A). In addition, we also showed that the inhibitor of PI3 K/Akt (LY, 50 μM), NF-κB (Bay, 10 μM), ERK1/2 (PD, 7 μM), and p38 MAPK (SB, 50 μM) significantly decreased the viability of A549 cells (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, bufalin at concentrations of 2.5–10 μM induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in G1 phase in A549 cells after the cells were treated for 48 h (Fig. 2B). These results partially explain why bufalin has therapeutic and/or adjuvant therapeutic effects on treatment of some patients with lung cancer.

Fig. 2.

Effects of bufalin (BF) on proliferation and induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in A549 cells. A The cells were treated for 48 and 72 h with the indicated concentrations of bufalin (BF1/2.5, BF5/5, BF10/10 μM), LY/50 μM, Bay/10 μM, PD/7 μM, and SB/50 μM. The cells in control group were treated with DMSO [0.1% (v/v), final concentration]. The rate of cell viability was determined by the MTT assay. LY, Bay, PD, and SB are the inhibitors of PI3 K/Akt, NF-κB, p44 (ERK1/2) and p38 MAPK, respectively. B Induction of apoptosis (cells in Sub-G1 phase) and cell cycle arrest (in G1 phase) in A549 cells by BF was analyzed by flow cytometry. The cells were treated for 48 h with BF at concentrations of 2.5, 5 and 10 μM. The data are presented as the mean ± SD (Bar) for each group (n = 6). The figures (A, B) are the representative of 3 similar experiments performed. Values with different letters (a–e) differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Bufalin reduces the protein levels of Bcl-2/Bax, cyclin D1 and COX-2 and enhances the protein levels of cytosolic cytochrom c, caspase-3, PARP-1, p53 and p21WAF1 in A549 cells

To understand the mechanisms of action of bufalin against proliferation and on induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in A549 cells, we studied the effects of bufalin on related protein expressions. Our results showed that bufalin at 2.5–10 μM reduced the ratios of Bcl-2/Bax proteins (Fig. 3A) and cyclin D1 (Fig. 4C) protein expression as well as the COX-2 protein level (Fig. 4D) in A549 cells. In addition, bufalin at these concentrations also enhanced the protein expressions of cytosolic/mitochondrial cytochrome c (ratio) (Fig. 3B), caspase-3 (Fig. 3C), the cleavage of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) (Fig. 3D), tumor suppressor p53 (Fig. 4A) and endogenous cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 WAF1/CIP1 (Fig. 4B) in A549 cells. In addition, the inhibitor of PI3 K/Akt (LY) and NF-κB (Bay) showed significant suppression of protein expressions of Bcl-2, cyclin D1 and COX-2 and increase in the protein levels of Bax, cytosolic cytochrome c, caspase-3, the cleavage of PARP, p53 and p21 WAF1 in A549 cells (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Effects of bufalin (BF) on protein expressions of Bcl-2/Bax (A), cytosolic and mitochondrial cytochrome c (cyto c) (B), caspase-3/procaspase-3 (C), and PARP-1 (D) in A549 cells. The cells were treated for 48 h with BF (BF1/2.5, BF5/5, BF10/10 μM), Bay (10 μM) and LY (50 μM). The protein expressions were analyzed by Western Blotting. The optical density (OD) of the band in each panel is normalized to β-actin, respectively. The OD value in each panel is relative to that of control [0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle] which is designated as 100%. The average OD value and standard deviation from three assays were calculated. The OD value of the band (normalized to β-actin) in each panel shown as mean ± SD is relative to that of the control designated as 100%. The ratios of each band relative to the control are designated as the ratios (%) of protein expression. LY and Bay are the inhibitors of PI3 K/Akt and NF-κB, respectively. For one experiment, 3 assays were carried out and only one set of gels is shown. Values with different letters (a–e) differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Fig. 4.

Effects of bufalin (BF) on protein expressions of p53 (A), p21WAF1 (B), cyclin D1 (C) and COX-2 (D) in A549 cells. The cells were treated for 48 h with BF (BF1/2.5, BF5/5, BF10/10 μM), Bay (10 μM) and LY (50 μM). The protein expressions were analyzed by Western Blotting. The optical density (OD) of the band in each panel is normalized to β-actin, respectively. The OD value in each panel is relative to that of control [0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle] which is designated as 100%. The average OD value and standard deviation from three assays were calculated. The OD value of the band (normalized to β-actin) in each panel shown as mean ± SD is relative to that of the control designated as 100%. The ratios of each band relative to the control are designated as the ratios (%) of protein expression. LY and Bay are the inhibitors of PI3 K/Akt, and NF-κB, respectively. For one experiment, 3 assays were carried out and only one set of gels is shown. Values with different letters (a–e) differ significantly (p < 0.05)

One of the main regulatory steps of apoptotic cell death is controlled by the ratio of antiapoptotic and proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family of proteins, which determines the susceptibility to apoptosis. Bax, a proapoptotic factor of the Bcl-2 family, is found in monomeric form in the cytosol or is loosely attached to the membranes under normal conditions. Following a death stimulus, cytosolic and monomeric Bax translocates to the mitochondria where it becomes an integral membrane protein and cross-linkable as a homodimer allowing for the release of factors from the mitochondria, such as cytochrome c, to propagate the apoptotic pathway (Oltvai et al. 1993). Bcl-2 and its related proteins control the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria (Reed 1997). Hallmarks of the apoptotic process include the activation of cysteine proteases, which represent both initiators and executors of cell death. In the cytosol, cytochrome c activates caspase-9, which in turn activates the effector caspases such as caspase-3 and caspase-7 (Stennicke and Salvesen 2000). In the present study, we observed that bufalin reduced the antiapoptotic/proapoptotic Bcl-2/Bax ratio (Fig. 3A). In addition, bufalin caused the release of cytocrome c from the mitochondria (Fig. 3B) and subsequently increased caspase-3 activity (Fig. 3C). Caspase-3 is synthesized as a 35-kDa inactive precursor (procaspase-3), which is proteolytically cleaved to produce a mature enzyme composed of 17-kDa fragments. The procaspase-3 protein was reduced and the caspase-3 in cleaved form was increased in the apoptotic A549 cells after the cells were treated with bufalin at the concentrations of 2.5–10 μM (Fig. 3C). In addition, we observed the cleavage of PARP-1, substrate of caspase-3, in A549 cells treated with 2.5–10 μM of bufalin (Fig. 3D).

The tumor suppressor protein p21 WAF1/CIP1 acts as an inhibitor of cell cycle progression. It functions in stoichiometric relationships forming heterotrimeric complexes with cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases. In association with CDK2 complexes, it serves to inhibit kinase activity and block progression through G1/S (Pestell et al. 1999). When p53 is phosphorylated under UV damage or the treatment with anticancer agents, it upregulates p21 transcription via a p53 responsive element (Wang and Prives 1995). Activation of p53 can lead to either cell cycle arrest and DNA repair or apoptosis (Levine 1997). In the present study, we observed that the protein levels of p53 (Fig. 4A) and p21 WAF1 (Fig. 4B) increased by more than 4 and twofold, respectively and Cyclin D1 (Fig. 4C) decreased by 50% in A549 cells by bufalin treatment at 10 μM. In addition, we also observed that bufalin at 2.5 to 10 μM displayed a strong effect on suppression of the COX-2 protein expression in A549 cells (Fig. 4D).

Taken together, all these results show that bufalin inhibits the proliferation of A549 cells and induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest by reducing Bcl-2/Bax ratio and activating the mitochondrial and caspase-3 pathway as well as affecting the cell cycle regulators such as p53, p21 WAF1 and cyclin D1 in A549 cells.

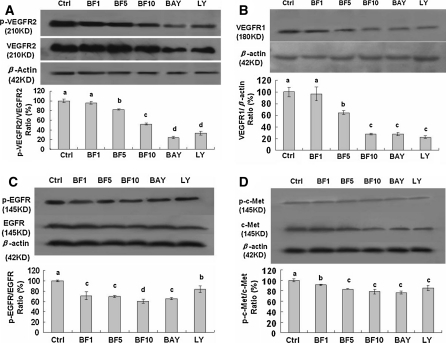

Bufalin reduces the receptor phosphorylation and/or protein expression of VEGFR2, VEGFR1, EGFR, and c-Met in A549 cells

The activated receptors such as VEGFR, EGFR, and c-Met play very important roles in the proliferation of cancer cells including lung cancer cells (Colon et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2008; Morelli et al. 2006; Naumov et al. 2009; Puri and Salgia 2008). In order to clarify the bufalin-targeted receptors in A549 cells, we studied the effects of bufalin on the related receptor phosphorylation and expressions in A549 cells. We have confirmed that bufalin at 2.5–10 μM significantly inhibited the phosphorylation and expressions of VEGFR2 (Fig. 5A), EGFR (Fig. 5C), and c-Met (Fig. 5D) in A549 cells. Bufalin at the concentration of 10 μM reduced the levels of phosphorylation of VEGFR2, EGFR, and c-Met by 50%, 40% and 22% and the protein expressions of VEGFR2, EGFR, and c-Met by 18%, 33% and 17%, respectively. Bufalin at 10 μM reduced the VEGFR1 (Fig. 5B) protein expression by 72% in A549 cells. In addition, the inhibitor of PI3 K/Akt (LY) and NF-κB (Bay) also showed inhibitory effects on the phosphorylation and expressions of these receptors (Fig. 5) in A549 cells. Down-regulation of the receptor phosphorylation and protein expressions in A549 cells by bufalin could greatly contribute to the suppression of their downstream targets and the receptors-mediated PI3 K/Akt and NF-κB as well as the related signaling pathways, and thus leads to inhibition of the proliferation in A549 cells.

Fig. 5.

Effects of bufalin (BF) on receptor protein expressions and phosphorylation of pVEGFR2/VEGFR2 (A), VEGFR1 (B), pEGFR/EGFR (C), and p–c-Met/c-Met (D) in A549 cells. The cells were treated for 30 min with BF (BF1/2.5, BF5/5, BF10/10 μM), Bay (10 μM) and LY (50 μM). The protein expressions and phosphorylation were analyzed by Western Blotting. The optical density (OD) of the band in each panel is normalized to β-actin, respectively. The OD value in each panel is relative to that of control [0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle] which is designated as 100%. The average OD value and standard deviation from three assays were calculated. The OD value of the band (normalized to β-actin) in each panel shown as mean ± SD is relative to that of the control designated as 100%. The ratios of each band relative to the control are designated as the ratios (%) of protein expression. LY and Bay are the inhibitors of PI3 K/Akt and NF-κB, respectively. For one experiment, 3 assays were carried out and only one set of gels is shown. Values with different letters (a–d) differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Bufalin reduces the phosphorylation and protein expression of Akt, NF-κB, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK in A549 cells

In order to further confirm the inhibitory effects of bufalin on the receptors-mediated signaling pathways related to the proliferation of A549 cells, we investigated the effects of bufalin on the phosphorylation and expressions of Akt, MAP kinases p44/42 (ERK1/2) and p38 as well as NF-κB in A549 cells. Our results show that bufalin at 2.5–10 μM significantly suppressed the phosphorylation and expressions of Akt (Fig. 6A), ERK1/2 (Fig. 6B), p38 MAP kinase (Fig. 6C), and NF-κB (Fig. 6D) in A549 cells. In addition, the inhibitor of PI3 K/Akt (LY), ERK1/2 (PD), p38 MAPK (SB) and NF-κB (Bay) significantly suppressed the phosphorylation and protein expressions of Akt, ERK1/2, p38 MAPK and NF-κB in A549 cells, respectively (Fig. 6A–D).

Fig. 6.

Effects of bufalin (BF) on protein expressions and phosphorylation of pAkt/Akt (A), pp44(42)/p44(42) (B), pp38/p38 (C), and p–c-Met/c-Met (D) in A549 cells. The cells were treated for 30 min with BF (BF1/2.5, BF5/5, BF10/10 μM), Bay (10 μM), LY (50 μM), PD (7 μM) and SB (50 μM). The protein expressions and phosphorylation were analyzed by Western Blotting. The optical density (OD) of the band in each panel is normalized to β-actin, respectively. The OD value in each panel is relative to that of control [0.1% (v/v) DMSO vehicle] which is designated as 100%. The average OD value and standard deviation from three assays were calculated. The OD value of the band (normalized to β-actin) in each panel shown as mean ± SD is relative to that of the control designated as 100%. The ratios of each band relative to the control are designated as the ratios (%) of protein expression. LY, Bay, PD, and SB are the inhibitors of PI3 K/Akt, NF-κB, p44 (ERK1/2), and p38 MAPK, respectively. For one experiment, 3 assays were carried out and only one set of gels is shown. Values with different letters (a–d) differ significantly (p < 0.05)

Akt is a cytosolic signal transduction protein kinase that plays an important role in cell survival pathways (West et al. 2002). Induction of Akt activity is primarily dependent on the PI3 K pathway. Akt can be activated by many forms of cellular stress, such as those observed under treatment with anticancer agents (West et al. 2002). Once activation, Akt controls cellular functions such as apoptosis, cell cycle, gene transcription, and protein synthesis through the phosphorylation of downstream substrates such as NF-κB, p53 and COX-2 (West et al. 2002). NF-κB is a nuclear transcription regulator with a specific motif for Bcl-2 transcription (Marsden et al. 2002; Wang et al. 1996). Activation of p-Akt and the NF-κB/Bcl-2 pathway leads to inhibition of chemotherapy-induced apoptosis, which results in treatment resistance (Wang et al. 1996). Our previous results confirmed that suppression of Akt and the NF-κB/Bcl-2 pathway by anticancer agents inhibited growth and induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in A549 cells and breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells (Wang et al. 2009; Yu et al. 2009). In the present study, we indicated that bufalin and the inhibitor of PI3 K/Akt (LY294002) and of NF-κB (Bay) inhibited the A549 cell proliferation and the PI3 K/Akt and NF-κB pathway by suppressing the phosphorylation and expressions of Akt and NF-κB and activating the apoptotic pathway of Bcl-2/Bax-mitochondrial-caspase-3 in A549 cells.

The p53 is the most extensively studied tumor suppressor gene in human cancer. The p53 gene product is involved in multiple pivotal cellular processes as a potent transcriptional regulator, and one of its most important roles is the regulation of apoptosis (Vousden and Lu 2002). Up-regulation of wild type (WT) of p53 in human NSCLC is a favorable prognostic factor and is associated with a significantly longer survival (Lee et al. 1995). Rescue of p53-induced apoptosis by survival factors has been associated with the activation of Akt kinase (Sabbatini and McCormick 1999). Akt can phosphorylate and activate MDM2, thereby enhancing the degradation of p53 (Mayo and Donner 2001; Zhou et al. 2001). Thus, up-regulation of WT p53 in A549 cells after treatment with either bufalin or inhibitor of PI3 K/Akt (LY), as observed in our study, could be explained by down-regulation of the pAkt/MDM2 pathway. In addition to its interplay in the regulation of apoptosis, WT p53 has been shown to directly affect Bax and Bcl-2 expressions. Thus, WT p53 is able to mediate repression of the Bcl-2 gene and the transactivation of Bax (Miyashita et al. 1994). Therefore, up-regulation of WT p53 could be responsible for the decrease in the Bcl-2/Bax ratio in A549 after treatment with bufalin.

COX-2, a marker of poor prognosis in stage I NSCLC, also is a promising target in treating NSCLC (Khuri et al. 2001). Inhibition of p44/42 MAPK-dependent pathway (Chang et al. 2002), p38 MAPK, or pAkt and NF-κB pathways (Lin et al. 2002; Shishodia et al. 2004) led to down-regulation of synthesis of COX-2 in A549 cells. In the present study, suppression of the pathways of p44/42 and p38 MAPKs, pAkt and p-NF-κB by bufalin could be responsible for the reduction of COX-2 expression in A549 cells.

The ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways can be activated in response to a diverse range of extracellular stimuli including mitogens, growth factors, and cytokines (Baccarini 2005; Meloche and Pouysségur 2007; Roux and Blenis 2004) and are important targets in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer (Roberts and Der 2007). Suppression of the activated EGFR and ERK1/2 and p38 MAPKs as well as Akt signaling pathways led to inhibition of the proliferation of A549 cells (Baldys et al. 2007; Nguyen et al. 2004; Recchia et al. 2009; Su et al. 2010). There has been the cross-talk in EGFR and c-Met pathways in A549 cells which is related to the A549 cell proliferation (Puri and Salgia 2008). Suppression of EGFR, VEGFR, and c-Met led to inhibition of A549 cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo (Colon et al. 2009; Kim et al. 2008; Morelli et al. 2006; Naumov et al. 2009). Here we have confirmed that bufalin remarkably suppressed the VEGFR1, VEGFR2, EGFR and c-Met receptors and their downstream targets such as p44/42, p38, Akt and NF-kB in A549 cells, which could contribute to inhibition of A549 cell proliferation.

In summary, our present results have demonstrated that bufalin suppressed the A549 cell proliferation and induced the apoptosis and cell cycle arrest at G1 phase by targeting the EGFR, VEGFR1, VEGFR2, and c-Met receptors-mediated signaling pathways of Akt, p44/42 and p38 MAPKs, and NF-κB in A549 cells. All these findings suggest that bufalin may have the wide therapeutic and/or adjuvant therapeutic application in the treatment of human NSCLC.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend our thanks to Drs. Jianyuan Li and Shaohua Jin for FACS analysis. This work is supported in part by grants from the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China to G.Z, from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security of the People’s Republic of China to G.Z, Projects of Yantai University to GZ, Project from the National Natural Science Foundation of China to GZ (No. 30973553), and grants from the Department of Science and Technology of Shandong Province to GZ (Y2008C71; 2009GG10002087).

Conflict of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- BF

Bufalin

- MAPKs

Mitogen-activated protein kinases

- ERK½

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor κB

- VEGFR

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- LY

Ly294002

- Bay

Bay 11-7082

- SB

SB203580

- PD

PD98059

- PARP

Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

- Cyto C

Cytochrome c

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- NSCLC

Non–small cell lung cancer

Footnotes

Yongtao Jiang and Ying Zhang contributed equally to this work.

References

- Baccarini M. Second nature: biological functions of the Raf-1 “kinase”. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3271–3277. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldys A, Pande P, Mosleh T, Park SH, Aust AE. Apoptosis induced by crocidolite asbestos in human lung epithelial cells involves inactivation of Akt and MAPK pathways. Apoptosis. 2007;12:433–447. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0577-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang MS, Lee WS, Teng CM, Lee HM, Sheu JR, Hsiao G, Lin CH. YC-1 increases cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression through protein kinase G- and p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathways in A549 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:558–567. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon J, Basha MR, Madero-Visbal R, Konduri S, Baker CH, Herrera LJ, Safe S, Sheikh-Hamad D, Abudayyeh A, Alvarado B, Abdelrahim M (2009) Tolfenamic acid decreases c-Met expression through Sp proteins degradation and inhibits lung cancer cells growth and tumor formation in orthotopic mice. Invest New Drugs, 23 Oct 2009 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gu W, Han KQ, Su YH, Huang XQ, Ling CQ. Inhibition action of bufalin on human transplanted hepatocellular tumor and its effects on expressions of Bcl-2 and Bax proteins in nude mice. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2007;5:155–159. doi: 10.3736/jcim20070211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khuri FR, Wu H, Lee JJ, Kemp BL, Lotan R, Lippman SM, Feng L, Hong WK, Xu XC. Cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression is a marker of poor prognosis in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee UJ, Kim MN, Lee EJ, Kim JY, Lee MY, Choung S, Kim YJ, Choi YC. MicroRNA miR-199a regulates the MET proto-oncogene and the downstream extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2) J Biol Chem. 2008;283:18158–18166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800186200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Yoon A, Kalapurakal SK, Ro JY, Lee JJ, Tu N, Hittelman WN, Hong WK. Expression of p53 oncoprotein in non-small-cell lung cancer: a favorable prognostic factor. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1893–1903. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.8.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CH, Kuan IH, Wang CH, Lee HM, Lee WS, Sheu JR, Hsiao G, Wu CH, Kuo HP. Lipoteichoic acid-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression requires activations of p44/42 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;450:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(02)02002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Duan H, Luan J, Yagasaki K, Zhang G. Effects of theanine on growth of human lung cancer and leukemia cells as well as migration and invasion of human lung cancer cells. Cytotechnology. 2009;59:211–217. doi: 10.1007/s10616-009-9223-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan J, Duan H, Liu Q, Yagasaki K, Zhang G (2010) Inhibitory effects of norcantharidin against human lung cancer cell growth and migration. Cytotechnology 20 Jan 2010 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Marsden VS, O’Connor L, O’Reilly LA, Silke J, Metcalf D, Ekert PG, Huang DC, Cecconi F, Kuida K, Tomaselli KJ, Roy S, Nicholson DW, Vaux DL, Bouillet P, Adams JM, Strasser A. Apoptosis initiated by Bcl-2-regulated caspase activation independently of the cytochrome c/Apaf-1/caspase-9 apoptosome. Nature. 2002;419:634–637. doi: 10.1038/nature01101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo LD, Donner DB. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway promotes translocation of Mdm2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11598–11603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181181198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meloche S, Pouysségur J. The ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway as a master regulator of the G1- to S-phase transition. Oncogene. 2007;26:3227–3239. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Z, Yang P, Shen Y, Bei W, Zhang Y, Ge Y, Newman RA, Cohen L, Liu L, Thornton B, Chang DZ, Liao Z, Kurzrock R. Pilot study of huachansu in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, nonsmall-cell lung cancer, or pancreatic cancer. Cancer. 2009;115:5309–5318. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T, Krajewski S, Krajewska M, Wang HG, Lin HK, Liebermann DA, Hoffman B, Reed JC. Tumor suppressor p53 is a regulator of bcl-2 and bax gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Oncogene. 1994;9:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli MP, Cascone T, Troiani T, Tuccillo C, Bianco R, Normanno N, Romano M, Veneziani BM, Fontanini G, Eckhardt SG, Pacido S, Tortora G, Ciardiello F. Anti-tumor activity of the combination of cetuximab, an anti-EGFR blocking monoclonal antibody and ZD6474, an inhibitor of VEGFR and EGFR tyrosine kinases. Cell Physiol. 2006;208:344–353. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumov GN, Nilsson MB, Cascone T, Briggs A, Straume O, Akslen LA, Lifshits E, Byers LA, Xu L, Wu HK, Jänne P, Kobayashi S, Halmos B, Tenen D, Tang XM, Engelman J, Yeap B, Folkman J, Johnson BE, Heymach JV. Combined vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) blockade inhibits tumor growth in xenograft models of EGFR inhibitor resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3484–3494. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TT, Tran E, Nguyen TH, Do PT, Huynh TH, Huynh H. The role of activated MEK-ERK pathway in quercetin-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis in A549 lung cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:647–659. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestell RG, Albanese C, Reutens AT, Segall JE, Lee RJ, Arnold A. The cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in hormonal regulation of proliferation and differentiation. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:501–534. doi: 10.1210/er.20.4.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri N, Salgia R. Synergism of EGFR and c-Met pathways, cross-talk and inhibition, in non-small cell lung cancer. J Carcinog. 2008;7:9. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.44372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchia AG, Musti AM, Lanzino M, Panno ML, Turano E, Zumpano R, Belfiore A, Andò S, Maggiolini M. A cross-talk between the androgen receptor and the epidermal growth factor receptor leads to p38MAPK-dependent activation of mTOR and cyclinD1 expression in prostate and lung cancer cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed JC. Bcl-2 family proteins: regulators of apoptosis and chemoresistance inhematologic malignancies. Semin Hematol. 1997;34:S9–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PJ, Der CJ. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene. 2007;26:3291–3310. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux PP, Blenis J. ERK and p38 MAPK-activated protein kinases: a family of protein kinases with diverse biological functions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68:320–344. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.320-344.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbatini P, McCormick F. Phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase (PI3 K) and PKB/Akt delay the onset of p53-mediated, transcriptionally dependent apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24263–24269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishodia S, Koul D, Aggarwal BB. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates TNF-induced NF-kappa B activation through inhibition of activation of I kappa B alpha kinase and Akt in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with suppression of COX-2 synthesis. J Immunol. 2004;173:2011–2022. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Caspases—controlling intracellular signals by protease zymogen activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su JC, Lin KL, Chien CM, Tseng CH, Chen YL, Chang LS, Lin SR. Naphtho[1, 2-b]furan-4, 5-dione inactivates EGFR and PI3 K/Akt signaling pathways in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Life Sci. 2010;86:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai N, Ueda T, Nishida M, Nasu K, Narahara H. Bufalin induces growth inhibition, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human endometrial and ovarian cancer cells. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21:637–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell’s response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Prives C. Increased and altered DNA binding of human p53 by S and G2/M but not G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Nature. 1995;376:88–91. doi: 10.1038/376088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS., Jr TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Science. 1996;274:784–787. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Liu K, Yu P, Liu K, Luan J, Duan H, Lu Z, Wang F, Wu E, Yagasaki K, Zhang G. Suppression of growth, migration and invasion of highly-metastatic human breast cancer cells by berbamine and its molecular mechanisms of action. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:81. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe M, Masuda Y, Nakajo S, Yoshida T, Kuroiwa Y, Nakaya K. The cooperative interaction of two different signaling pathways in response to bufalin induces apoptosis in human leukemia U937 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14067–14072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West KA, Castillo SS, Dennis PA. Activation of the PI3 K/Akt pathway and chemotherapeutic resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2002;5:234–248. doi: 10.1016/S1368-7646(02)00120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuharu S, Eiji I, Chihiro I. Effect of the water-soluble and non-dialyzable fraction isolated from senso (Chan Su) on lymphocyte proliferation and natural killer activity in C3H mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:256–260. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CH, Kan SF, Pu HF, Jea Chien E, Wang PS. Apoptotic signaling in bufalin- and cinobufagin-treated androgen-dependent and -independent human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:2467–2476. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, Liu Q, Liu K, Yagasaki K, Wu E, Zhang G. Matrine suppresses breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion via VEGF-Akt-NF-kappaB signaling. Cytotechnology. 2009;59:219–229. doi: 10.1007/s10616-009-9225-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G, Miura Y, Yagasaki K. Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in cancer cells by in vivo metabolites of teas. Nutr Cancer. 2000;38:265–273. doi: 10.1207/S15327914NC382_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zhang H, Yu P, Liu Q, Liu K, Duan H, Luan G, Yagasaki K, Zhang G. Effects of matrine against the growth of human lung cancer and hepatoma cells as well as lung cancer cell migration. Cytotechnology. 2009;59:191–200. doi: 10.1007/s10616-009-9211-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou BP, Liao Y, Xia W, Zou Y, Spohn B, Hung MC. HER-2/neu induces p53 ubiquitination via Akt-mediated MDM2 phosphorylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:973–982. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]