Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cells exist in specific niches in the bone marrow, and generate either more stem cells or differentiated hematopoietic progeny. In such microenvironments, cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions are as important as soluble factors such as cytokines. To provide a similar environment for in vitro studies, a three-dimensional culture technique is necessary. In this manuscript, we report the development of a three-dimensional culture system for murine bone marrow mononuclear cells (mBMMNCs) using polyurethane foam (PUF) as a scaffold. The mBMMNCs were inoculated into two kinds of PUF disks with different surface properties, and cultured without exogenous growth factors. After seeding the inside of the PUF pores with mBMMNCs, PUF disks were capable of supporting adherent cell growth and continuous cell production for up to 90 days. On days 21–24, most nonadherent cells were CD45 positive, and some of the cells were of the erythroid type. From comparisons of the cell growth in each PUF material, the mBMMNC culture in PUF-W1 produced more cells than the PUF-R4 culture. However, the mBMMNC culture in PUF-W1 had no advantages over PUF-R4 with regard to the maintenance of immature hematopoietic cells. The results of scanning electron microscopy and colony-forming assays confirmed the value of the different three dimensional cultures.

Keywords: Hematopoietic stem cells, Three dimensional culture, Polyurethane foam

Introduction

In vivo hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) have the ability to self-renew and to generate differentiated progeny of all blood cell lineages (Emerson 1996). The bone marrow is home to few HSCs, and the site for hematopoiesis. The continuous regeneration of blood cells depends on the self-renewal of these HSCs. The HSCs adhere to the surface of trabecular bone through bone marrow stromal cells. The stromal cell layer provides physical support and some cytokines to the hematopoietic cells (Panoskaltsis et al. 2005).

One of the problems facing the growth of hematopoiesis in vivo is continuous cell culture. Stromal-dependent culture in a monolayer such as the Dexter culture system requires the addition of a large amount of cytokines to induce the proliferation of HSCs and hematopoietic progenitors (Dexter et al. 1977; Koller et al. 1992; Kanai et al. 2000; Yoshida et al. 1997; Ebihara et al. 1997). To more effectively use cell–cell or cell-ECM interactions, several culture systems have been developed (Takagi 2005; Tomimori et al. 2000; Bennaceur-Griscelli et al. 1999). These new culture systems include polyvinyl formal, nonwoven disks, porous microspheres, and so on (Tomimori et al. 2000; Naughton et al. 1987; Tun et al. 2002). These 3-D porous carriers have a larger surface area than the conventional monolayer culture system and promote a high cell density in culture (Li et al. 2001; Naughton and Naughton 1989). In these reports, the contribution of the novel culture conditions to maintenance or proliferation of HSCs and hematopoietic progenitor cells has been documented. It is hoped that a 3-D culture can establish a continuous blood cell production system from cultured HSCs.

In order for a 3D culture system to achieve stable cell production, the investigation of a porous carrier is indispensable. A suitable carrier and culture method are required for the reconstruction of the hematopoietic microenvironment in vitro. We have previously developed a 3-D culture technique (mass culture system) using a polyurethane foam (PUF) culture as the culture substratum. PUF has a sponge-like macro porous structure, with each pore comprised of smooth thin films and thick skeletons (Fig. 1). In this study, we investigated the effect of the scaffold construction on the reconstruction of the hematopoietic microenvironment in vitro.

Fig. 1.

SEM micrographs of the PUF-W1 scaffolds: a side cross sectional view, b top cross sectional view

Methods

Cell preparation

Male C57BL6/J mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from Kyudo Co., Ltd (Kumamoto, Japan). Mouse bone marrow cells were isolated from the femurs and tibias by flushing with CMF-PBS using a 1.0 mL syringe and 26 gauge needles (Tun et al. 2002). Mouse bone marrow mononuclear cells (mBMMNCs) were separated by density gradient separation in percoll (1.077 g/mL, Sigma) (Palsson et al. 1993). mBMMNCs were suspended in IMDM (Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium, Sigma) supplemented with 20% horse serum (Gibco), 5 U/mL Penicillin and 5 μg/mL Streptomycin (Gibco).

PUF 3D culture

PUF was kindly donated by Inoac (Nagoya, Japan). It has a sponge-like macro porous structure with each pore consisting of smooth thin films and thick skeletons (Ijima et al. 1998). The PUF block was cut into a flat disk (with diameter of 11 mm and thickness of 1.0 mm). We used two kinds of PUF (W1, R4) with different surfaces and structural properties (Table 1). Each PUF disk was placed in a 12-well plate for static culture. mBMMNCs were seeded onto PUF disks at 3.2 × 106 cells per 1.6 mL culture medium and incubated in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2 at a temperature of 37 °C. The traditional 2D monolayer culture reported by Dexter et al. was performed as a control culture. Half of the culture medium volume was removed from each well, and then the same volume of fresh medium was added at 3 day intervals.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of two types of PUF

| PUF type | W1 | R4 |

|---|---|---|

| Contact angle (degree) | 47.8 ± 4.5 | 85.2 ± 2.3 |

| Pore size (μm) | 500 | 250 |

After day 12, the culture plates were transferred on a rotary shaker for mature cell release (Fig. 2). The PUF disks were transferred to a new 12-well plate with fresh culture medium at 3 day intervals. Then, non-adherent cells were harvested from old medium and measured as “Produced Cells”. On the other hand, adherent cells on the PUF surface were harvested as “Adherent Cells”. The average cell count of two wells is shown in Fig. 3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to study the cytomorphosis of the surface of the scaffolds.

Fig. 2.

A schematic diagram of the 3D culture configuration in PUF pores

Fig. 3.

Hematopoietic cell proliferation. a Produced Cell counts in each culture. Each 3 days old culture medium containing nonadherent cells was replaced, and cells were counted as Produced cells (n = 3 by 42 day, then, n = 1). b Cumulative cell production in each culture. c Adherent Cell counts at each 7 days, which adhered to PUF surfaces (n = 2). The symbols: (triangle) W1 culture, (circle) R4 culture, and (square) monolayer culture

Phenotype analysis of the produced cells

We evaluated the lineage-specific surface markers expressed by the Produced Cells by MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) at day 21–24. The cells released from PUF culture were labeled with Ter-119 MicroBeads or CD45 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec) as recommended by the manufacturer. Next, Ter119+ or CD45+ cells were isolated from the magnet-retained fraction with a MACS separation unit (Miltenyi Biotech).

Colony forming unit (CFU) assay

The cultured cells were washed and resuspended at a density of 1.0 × 105 cells/mL in IMDM containing 1% FBS. The CFU samples (0.3 mL) were added to the suspended medium to form 3.0 mL HSC-CFU complete with erythropoietin, and were tested in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi Biotec).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test. Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

We monitored the proliferation of non-adherent cells in PUF or monolayer cultures as an indicator of cell production (Fig. 3a, b). In the monolayer cultures, the cell production stopped by day 21. In both PUF cultures, the cell production from the PUF increased until day 33, and then began to decrease. The number of cells produced in W1 culture was higher than that of R4 culture. The W1 culture could be maintained for 90 days, and the R4 culture was maintained for 48 days.

Flow cytometry was used to estimate the number of Produced Cells. Based on the population of Ter119 or CD45 positive cells at day 21–24, almost 99% of the Produced Cells were hematopoietic cells, and 21.8–34.9% of these differentiated into the erythroid line without the addition of erythropoietin (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The expression of cell surface markers by mBMMNCs and Produced Cells in PUF culture at day 21–24. The cells were harvested from 18 wells and used for these evaluations. (open) W1 culture, (hatched) R4 culture, and (closed) fresh BMMNC

Figure 3c shows the changes in the number of Adherent Cells. The proliferation of the Adherent Cells was obviously occurring in PUF culture after day 14. In addition, the number of Adherent Cells remained fairly constant between day 14 and day 21. In order to investigate the morphology of the Adherent Cells, the cells on the two types of PUF pores were observed by scanning electron microscopy. The adherent Cells were observed to spread out in a hole in the PUF-W1 pore, and only in the upper half of the PUF-R4 disks (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

At day 32, SEM micrographs of adherent cells from mBMMNC culture on (a) PUF-W1 and (b) PUF-R4. It was observed that the stromal cells have spread into the PUF scaffolds (arrows). On the other hand, the extension from like fibroblast cells was not observed

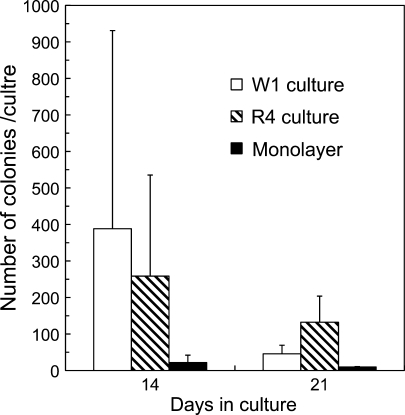

Although there were no significances among each culture condition, the number of colony-forming units (CFUs) in the PUF culture was greater than that in the monolayer culture (Fig. 6). When comparing the PUF cultures, the colony-forming ability of the cells was better maintained in the R4 culture than in the W1 culture. These results might be due to differences in cell density within each culture or due to the surface characteristics of each carrier.

Fig. 6.

Comparison in number of colony forming units in W1 culture, R4 culture and monolayer culture on day 14 and 21 (n = 4). The bars: (open) W1 culture, (hatched) R4 culture, and (closed) monolayer culture

Discussion

In each static culture after mBMMNC seeding, the cell number decreased (data not shown). In the PUF plates, the attached mBMMNCs grew to about 9.4 × 104 cells/cm2 by day 14, which was 18-fold higher than the monolayer culture, and cell production continued for a much longer duration of time (Fig. 3). These results indicate that the high cellular interaction in the PUF pores is important for reconstructing the hematopoietic microenvironment in vitro. The Adherent Cell proliferation and the maintenance of the colony-forming ability of the PUF culture was higher than that of the monolayer culture (Figs. 3, 4, 6). The cell proliferation suggests that stromal cells support the hematopoietic cells, and 3-D culture provides a better environment than 2-D culture for this support.

The PUF culture also compares favorably with other previously described 3-D culture techniques using Mouse BM cells (Tomimori et al. 2000; Tun et al. 2002). In these other culture systems, the growth of adherent cells was greater than the increase observed in our PUF culture from 2 to 5 weeks. However, the PUF culture achieved “continuous cell production” without adding growth factors for 91 days. It was observed that the Produced Cells from the PUF culture between 14 and 42 days were unable to form colonies. This suggests that mature cells might be released from PUF pores, and can be retrieved as by simple medium replacement and centrifugation. In addition, PUF is a low-cost material and easy to fabricate. Therefore, the use of PUF as a scaffold seems to be a useful method for producing hematopoietic cells for large-scale cultivation.

On the other hand, while the production of cells in the PUF culture was supported by the environment in the pore structure, it was also influenced by the PUF surface geometry. Adherent Cells inside each PUF, which were similar in cell number at day 14, grew at different rates. However, although cell production of R4 culture decreased remarkably after the 30th day, the number of nuclear cells on the PUF-R4 surface was similar between day 28 and day 42. Just before the PUF culture was completed, it was observed that adherent cells were rapidly exfoliated from each pore surface after the 45th day of R4 culture, or the 81st day of W1 culture. There was not a broad distinction between PUF cultures in morphological observations (Fig. 5). The different results with regard to longevity and differentiation might be due to the surface characteristics of the individual PUFs. Therefore, Adherent Cells in each PUF are likely to generate different cytokine and extracellular matrix effects. We are presently planning experiments with the OP9 stromal cell strain for a more detailed examination of the impact of the microenvironment.

On day 14, the cell number in the PUF culture was about 1.7 times the cell number (5.5 × 104 cells/cm2) of monolayer culture grown using Dexter’s culture conditions (Dexter et al. 1977). On the other hand, the surface area to volume ratio of PUF was estimated to be 109 cm2/cm3 (Matsushita et al. 1991). When the cell growth from day 14 to day 21 in the PUF inside and outside were compared, the Adherent Cells were found to have an approximately 2.5-fold higher growth rate than the Produced Cells. Furthermore, the cell production of the PUF culture peaked on the 30th day of cultivation. These results suggest that the entire area of the PUF surface was not covered by stromal cells in early stages of cultivation. Covering the surface more completely may therefore positively contribute to shortening the necessary preparation period and thereby increased the performance of PUF culture. This is similar to the comparison between 2D and 3D culture with the ST2 stromal cell line (Sasaki et al. 2002).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we herein demonstrated that the microenvironment in PUF disks affected the in vitro hematopoiesis of mBMMNCs, and that continuous cell production with no addition of growth factors was possible. Differences in the PUF surface geometry, and the covering of the PUF pores with stromal cells should therefore be the subject of future investigations.

Contributor Information

Tadasu Jozaki, Phone: +81-92-8022776, FAX: +81-92-8022796, Email: tjozaki@chem-eng.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Hiroshi Mizumoto, Phone: +81-92-8022759, FAX: +81-92-8022796, Email: hiroshi@chem-eng.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

Toshihisa Kajiwara, Phone: +81-92-8022746, FAX: +81-92-8022796, Email: kajiwara@chem-eng.kyushu-u.ac.jp.

References

- Bennaceur-Griscelli A, Tourino C, Izac B, Vainchenker W, Coulombel L. Murine stromal cells counteract the loss of long-term culture-initiating cell potential induced by cytokines in CD34+CD38low/neg human bone marrow cells. Blood. 1999;94:529–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter TM, Allen TD, Lajtha LG. Conditions controlling the proliferation of haemopoietic stem cells in vitro. J Cell Physiol. 1977;91:335–344. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040910303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara Y, Tsuji K, Lyman SD, Sui X, Yoshida M, Muraoka K, Yamada K, Tanaka R, Nakahata T. Synergistic action of Flt3 and gp130 signalings in human hematopoiesis. Blood. 1997;90:4363–4368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson SG. Ex vivo expansion of hematopoietic precursors, progenitors, and stem cells: the next generation of cellular therapeutics. Blood. 1996;87:3082–3088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ijima H, Nakazawa K, Mizumoto H, Matsushita T, Funatsu K. Formation of a spherical multicellular aggregate (spheroid) of animal cells in the pores of polyurethane foam as a cell culture substratum and its application to hybrid artificial liver. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 1998;9(7):765–778. doi: 10.1163/156856298X00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai M, Hirayama F, Yamaguchi M, Ohkawara J, Sato N, Fukazawa K, Yamashita K, Kuwabara M, Ikeda H, Ikebuchi K. Stromal cell-dependent ex vivo expansion of human cord blood progenitors and augmentation of transplantable stem cell activity. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:837–844. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller M, Bender JG, Papoutsakis ET, Miller WM. Effects of synergistic cytokine combinations, low oxygen, and irradiated stroma on the expansion of human cord blood progenitors. Blood. 1992;80:403–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kniss DA, Yang ST, Lasky LC. Human cord cell hematopoiesis in three-dimensional nonwoven fibrous matrices: in vitro simulation of the marrow microenvironment. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2001;10:355–368. doi: 10.1089/152581601750288966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Hidaka H, Kamihata K, Kawakubo Y, Funatsu K. High density culture of anchorage-dependent animal cells by polyurethane foam packed-bed culture systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1991;35:159–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00184680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton BA, Naughton GK. Hematopoiesis on nylon mesh templates. Comparative long-term bone-marrow culture and the influence of stromal support cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;554:125–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb22415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton BA, Preti RA, Naughton GK. Hematopoiesis on nylon mesh templates. I. Long-term culture of rat bone marrow cells. J Med. 1987;18(3–4):219–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palsson BO, Paek SH, Schwartz RM, Palsson M, Lee GM, Emerson SG. Expansion of human bone marrow progenitor cells in a high cell density continuous perfusion system. Bio/Technology. 1993;11(3):368–372. doi: 10.1038/nbt0393-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panoskaltsis N, Mantalaris A, David Wu JH. Engineering a mimicry of bone marrow tissue ex vivo. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;100(1):28–35. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Takagi M, Soma T, Yoshida T. 3D culture of murine hematopoietic cells with spatial development of stromal cells in nonwoven fabrics. Cytotherapy. 2002;4(3):285–291. doi: 10.1080/146532402320219808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi M. Cell processing engineering for ex-vivo expansion of hematopoietic cells. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;99(3):189–196. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomimori Y, Takagi M, Yoshida T. The construction of an in vitro three-dimensional hematopoietic microenvironment for mouse bone marrow cells employing porous carriers. Cytotechnology. 2000;34:121–130. doi: 10.1023/A:1008157303025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tun T, Miyoshi H, Aung T, Takahashi S, Shimizu R, Kuroha T, Yamamoto M, Ohshima N. Effect of growth factors on ex vivo bone marrow cell expansion using three-dimensional matrix support. Artif Organs. 2002;26:333–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Tsuji K, Ebihara Y, Muraoka K, Tanaka R, Miyazaki H, Nakahata T. Thrombopoietin alone stimulates the early proliferation and survival of human erythroid, myeloid and multipotential progenitors in serum-free culture. Br J Haematol. 1997;98:254–264. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.2283045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]