Abstract

We report on the development of a monitoring test for recurrent breast cancer using metabolite profiling methods. Using a combination of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and two dimensional gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GCxGC-MS) methods, we analyzed the metabolite profiles of 257 retrospective serial serum samples from 56 previously diagnosed and surgically treated breast cancer patients. 116 of the serial samples were from 20 patients with recurrent breast cancer and 141 samples were from 36 patients with no clinical evidence of the disease during the approximately 6-year sample collection period. NMR and GCxGC-MS data were analyzed by multivariate statistical methods to compare identified metabolite signals between the recurrence and no evidence of disease samples. Eleven metabolite markers (7 from NMR and 4 from GCxGC-MS) were shortlisted from an analysis of all patient samples using logistic regression and 5-fold cross validation. A PLS-DA model built using these markers with leave one out cross validation provided a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 84% (AUROC =0.88). Strikingly, 55% of the patients could be correctly predicted to have recurrence 13 months (on average) before the recurrence was diagnosed clinically, representing a large improvement over the current breast cancer monitoring assay CA 27.29. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to develop and pre-validate a prediction model for early detection of recurrent breast cancer based on a metabolic profile. In particular, the combination of two advanced analytical methods, NMR and MS, provides a powerful approach for the early detection of recurrent breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast Cancer, Recurrence, Metabolomics, Metabolite Profiling, NMR, Gas Chromatography, CA 27.29

Introduction

Breast cancer remains the leading cause of death among women worldwide. It is the second leading cause of cancer death among women in the United States with nearly 255,000 new cases and 40,000 deaths expected in the year 2010 (1). Although breast cancer survival has improved over the past few decades owing to better diagnostic screening methods (2), it often recurs anywhere from 2 to 15 years following initial treatment, and can occur either locally in the same or contralateral breast or as a distant recurrence (metastasis). Recent studies by Brewster et al. of nearly 3,000 breast cancer patients showed that the recurrence rate 5 and 10 yrs after completion of adjuvant treatment were 11% and 20%, respectively (3). Numerous factors such as stage, grade and hormone receptor status are shown to have association with recurrence. Higher stage tumors have an increased propensity to recur. For example, a recent study reports recurrence rate of 7%, 11% and 13% after 5 yrs for stage I, II and III tumor cases, respectively (3). In addition, conditions such as lymph node invasion and absence of estrogen receptors are factors in a higher relapse rate and a shorter disease-free survival (4). Studies have shown that early detection of locally recurrent breast cancers can improve survival rate significantly (5, 6).

Common methods of routine surveillance for recurrent breast cancer include periodic mammography, self or physician-performed physical examination and blood tests. The performance of such tests are lacking and extensive investigations for surveillance have not proven effective (7). Often, mammography misses small local recurrences or leads to false positives resulting in suboptimal sensitivity and specificity and unnecessary biopsies. In view of the unmet need for more sensitive and earlier detection methods, the last decade or so has witnessed the development of a number of new approaches for detecting recurrent breast cancer and monitoring disease progression using blood based tumor markers or genetic profiles (8-11). The in vitro diagnostic (IVD) markers include carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cancer antigen (CA 15-3, CA 27.29), tissue polypeptide antigen (TPA), and tissue polypeptide specific antigen (TPS). Such molecular markers are thought to be promising since the outcome of the diagnosis based on these markers is independent of expertise and experience of the clinician and their use potentially avoids sampling errors commonly associated with conventional pathological tests such as histopathology. However, currently, these markers lack the desired sensitivity and/or specificity, and often respond late to recurrence, underscoring the need for alternative approaches (12, 13).

A new approach is to use metabolite profiling (or metabolomics) which can detect disease based on a panel of small molecules derived from the global or targeted analysis of metabolic profiles of samples such as blood and urine, and this approach is increasingly gaining interest (14, 15). Metabolite profiling utilizes high-resolution analytical methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and mass spectroscopy (MS) for the quantitative analysis of hundreds of small molecules (less than ∼ 1000 Da) present in biological samples (16). Owing to the complexity of the metabolic profile, multivariate statistical methods are extensively used for data analysis. The high sensitivity of metabolite profiles to even subtle stimuli can provide the means to detect the early onset of various biological perturbations in real time. Metabolite profiling has applications in a growing number of areas, including early disease diagnosis, investigation of metabolic pathways, pharmaceutical development, toxicology and nutritional studies (16-21). Moreover, the ability to link the metabolome, which constitutes the downstream products of cellular functions, to genotype and phenotype can provide a better understanding of complex biological states that promises routes to new therapy development.

In the present study, we apply metabolite profiling gg methods to investigate blood serum metabolites that are sensitive to recurrent breast cancer. We utilize a combination of NMR and two dimensional gas chromatography resolved MS (GCxGC-MS) methods to build and verify a model for early breast cancer recurrence detection based on a set of 257 retrospective serial samples. We compare the performance of the derived 11 metabolite biomarker model with that of the currently used molecular marker, CA 27.29, in particular for providing a sensitive test for follow-up surveillance of treated breast cancer patients. This is the first metabolomics study that combines the information rich analytical methods of NMR and MS to derive a sensitive and specific model for the early detection of recurrent breast cancer. The results indicate that such an approach may provide a new window for earlier treatment and its benefits.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

Subsequent to initial studies, where data remain unpublished, 56 breast cancer patients treated between 1997 and 2003 at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX) were enrolled through collaboration with Third Nerve, LLC. The cases studied average five longitudinal blood draws with a total evaluation of 257 retrospective serum samples (each ∼400 μL). Follow-up of these female patients included routine monitoring for recurrence as indicated by factors including CA 27.29, CEA, and/or CA125 IVD results, patient symptoms, initial breast cancer stage, hormone receptor and lymph node status. Twenty patients recurred within the sampling period while 36 remained with no evidence of disease (NED). A total of 116 serum samples were obtained from recurrent breast cancer patients; 67 were collected more than 3 months prior to clinically determined recurrence (Pre); 18 were collected within 3 months before/after recurrence (Within); and 31 were collected more than 3 months after recurrence diagnosis (Post). The remaining 141 samples comprise the cases remaining NED for at least two years beyond their sample collection period. Nearly all samples were evaluated for CA 27.29 values at the time of collection and therefore could be used for comparison. Study samples were maintained at -80 °C from collection until their transfer over dry ice to the evaluation laboratory at Purdue University where they were again stored frozen at -80 °C until this study was conducted. Serum samples and accompanying clinical data were appropriately de-identified prior to transfer into this study. Table 1 summarizes the clinical parameters and demographical characteristics of the cancer patients.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients used in this study.

| Clinical Diagnosis | Control | Recurrence | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | (patients) | Samples | (patients) | |

| No evidence of disease (NED) | 141 | (36) | ||

| Pre recurrence (Pre) | - | 67 | (20) | |

| Within recurrence (Within) | - | 18 | (18) | |

| Post recurrence (Post) | - | 31 | (20) | |

| Age Mean {Range} | 53 {37-75} | 55 {36-69} | ||

| Breast Cancer Stage | ||||

| Stage I | 47 | (11) | 7 | (1) |

| Stage II | 59 | (16) | 21 | (5) |

| Stage III | 10 | (3) | 34 | (6) |

| Unknown | 25 | (6) | 54 | (8) |

| Estrogen receptor status | ||||

| Positive | 65 | (15) | 67 | (11) |

| Negative | 64 | (18) | 33 | (7) |

| Unknown | 12 | (3) | 16 | (2) |

| Progesterone receptor status | ||||

| Positive | 52 | (13) | 71 | (11) |

| Negative | 77 | (20) | 29 | (7) |

| Unknown | 12 | (3) | 16 | (2) |

| CA27.29 | 140 | (36) | 92 | (19) |

| Site of Recurrence | ||||

| Bone | - | 37 | (6) | |

| Breast | - | 13 | (2) | |

| Liver | - | 11 | (2) | |

| Lung | - | 10 | (2) | |

| Skin | - | 6 | (2) | |

| Brain | - | 15 | (2) | |

| Lymph | - | 6 | (1) | |

| Multiple sites | - | 18 | (3) | |

1H NMR Spectroscopy

All NMR experiments were carried out at 25 °C on a Bruker DRX 500-MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe and triple-axis magnetic field gradients. Two 1H NMR spectra were measured for each sample, a standard 1D NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy) and CPMG (Carr-Purcell-Meiboom-Gill) pulse sequences coupled with water presaturation (22). For each spectrum, 32 transients were collected using 32k data points and a spectral width of 6000 Hz. The data were processed using Bruker XWINNMR software version 3.5 and saved in ASCII format for further analysis. Relative peak integrals were calculated using the total spectral sum and used for the analysis. (see Supplementary Materials for more NMR methodology details).

GCxGC-MS

Two dimensional GCxGC-MS analysis of derivatized samples was performed using a Pegasus 4D system (LECO, St. Joseph, MI) consisting of an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) coupled to a Pegasus time of flight mass spectrometer. LECO ChromaTOF software (version 4.10) was used for automatic peak detection and mass spectrum deconvolution. The NIST MS database (NIST MS Search 2.0, NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library; NIST 2002) was used for data processing and peak matching. The identified biomarker candidates were confirmed from the mass spectra and retention times of authentic commercial samples. Relative peak integrals were calculated with respect to the same metabolites in a pooled blood sample that was used as a quality control (see Supplementary Materials for more details).

Metabolite identification and selection

The NMR spectrum from each sample was aligned with reference to the TSP (3-(trimethylsilyl) propionic-(2,2,3,3-d4) acid sodium salt) signal at 0 ppm. Spectral regions within the range of 0.5 to 9.0 ppm were analyzed after excluding the region between 4.5 and 6.0 ppm that contained the residual water peak and urea signal. Twenty-two metabolite signals, corresponding to those of potential biomarkers initially identified in a study on early breast cancer detection involving over 400 patient samples (Asiago, unpublished results) were selected as biomarker candidates for further analysis. The statistical significance of each metabolite in the selected regions was determined by calculating the p-values using the Student's t-test in the training set.

To further enhance the pool of metabolites identified by NMR, additional metabolites were selected from MS analysis. From the nearly 300 compounds identified by similarity to known compounds in the NIST database, additional and unique metabolites were selected (Table S1). Eighteen metabolites that either (a) showed statistically significant differences between normal and primary breast cancer (Asiago, unpublished results), or (b) were related to the identified NMR putative biomarker candidates by pathway analysis, or (c) in a few cases had high similarity scores to the NIST database and had high chemical similarity to the other biomarker candidates, were selected for further analysis. A software program was developed in-house to extract these metabolite signals from the GCxGC-MS datasets. Based on the input value of m/z and a retention time range, the program integrates chromatography peaks for each metabolite after the metabolite's spectrum was matched to the characteristic experimental mass spectrum from the standard NIST library.

Development of prediction model and validation

In order to select the metabolites with highest scores for developing the prediction model, samples from NED, Post and Within recurrence groups were used as described in Supplementary Fig. S1. Pre samples were omitted to avoid any ambiguity in determining the correct disease status prior to clinical diagnosis. The samples were divided into five cross validation (CV) groups of patients. Initial multivariate analysis was performed using logistic regression modeling of the 22 NMR and 18 GCxGC-MS detected metabolite signals and was applied to the 4 CV groups; the resulting model was used to predict the class membership of the 5th CV group. The output of the logistic regression procedure is a ranked set of markers (23-25).

Based on their ranked performance, eleven metabolite markers (7 from NMR and 4 from GCxGC-MS) were then shortlisted for model building. NMR and MS data for these markers was then imported into Matlab software (Mathworks, MA) installed with the PLS toolbox (Eigenvector Research, Inc, version 4.0) for PLS-DA modeling. Leave one patient out cross validation was chosen and 5 latent variables (LV) were selected according to the root mean square error of cross validation (RMSECV) procedure. The R statistical package (version 2.8.0) was used to generate receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves. The sensitivity, specificity and the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of the PLS-DA weighted linear model was calculated and compared.

The scores from the 11 marker model were scaled to yield a range of 0-100, and the cutoff threshold value (score = 48) for recurrence status was determined by a judicious choice between sensitivity and specificity. The performance of the model with reference to the initial stage of the breast cancer, ER/PR status, and the site of recurrence was also assessed.

Finally, the performance of the NMR and MS metabolite markers was also tested using a second statistical approach as described in Supplementary Fig. S2. In this case the samples were split randomly by patients into two parts, a “training set” consisting of 11 recurrence patients (17 Post, 6 Within, and 43 Pre samples) and 19 NED patients (74 samples), and a slightly smaller testing set consisting of 9 recurrence patients (14 Post, 12 Within, and 24 Pre samples) and 17 NED patients (67 samples) and analyzed. Multivariate logistic regression of the 22 NMR and 18 GCxGC-MS detected metabolite signals was applied to the training data set to optimize variable selection. Ten-fold cross validation was used during this procedure. The derived model was then validated on the testing set of samples, all from different patients than were used for variable selection and model building.

Results

Analysis of 1H NMR and GCxGC-MS spectra

NMR spectra of breast cancer serum samples obtained using the CPMG sequence were devoid of signals from macromolecules and clearly showed signals for a large number of small molecules including sugars, amino acids, amines and carboxylic acids. A representative NMR spectrum from a Post patient is shown in Supplementary Fig. S3a. Individual metabolites were identified using NMR databases (26, 27). Supplementary Fig. S3b shows a typical GCxGC-MS spectrum for the same recurrent breast cancer patient as shown in Fig. S3a. Identification of the metabolites in the GCxGC-MS spectra was based on the comparison of the experimental mass spectrum with that in the NIST database, and the assignments were further confirmed by comparing with the GCxGC-MS spectrum of the authentic commercial compounds for the 18 MS detected metabolites of interest. An example of this validation procedure for glutamic acid is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Biomarker selection and validation

Initial data analysis was focused on testing the performance of the 22 metabolites detected by NMR (Asiago, unpublished results) and 18 biomarker candidates selected from the mass spectra (as described above in the Experimental Section). From these data, we selected the markers with highest rank to maximize diagnostic accuracy. Making use of the logistic regression variable selection protocol described above, a set of 11 markers (7 from NMR and 4 from MS) were selected based on their highest ranking and predictive accuracy. Table 2 shows the list of 11 markers and their p-values for Pre vs. NED and Within and Post vs. NED comparisons using all samples. In general, the p-values of these markers were low for Within and Post vs. NED, except for four markers that were nevertheless highly ranked by logistic regression. In two of those four cases the metabolites showed low p-values for either Within vs. NED or Post vs. NED but not both.

Table 2.

P-values for 11 markers, 7 NMR (numbers 1-7) and 4 GCxGC-MS markers (numbers 8-11) for different groups using all samples; Within and Post recurrence vs. NED, Pre recurrence vs. NED as determined from the univariate Student's t-test.

| Metabolites | Within and Post vs. NED p-value | Pre-recurrence vs. NED p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Formate | 0.0022 | 0.2 |

| 2 | Histidine | 0.000041 | 0.18 |

| 3 | Proline | 0.018 | 0.9 |

| 4 | Choline | 0.000022 | 0.77 |

| 5 | Tyrosine | 0.25 | 0.1 |

| 6 | 3-hydroxybutyrate | 0.86 | 0.96 |

| 7 | Lactate | 0.96 | 0.54 |

| 8 | Glutamic acid | 0.000018 | 0.74 |

| 9 | N-acetyl-glycine | 0.01 | 0.96 |

| 10 | 3-hydroxy-2-methyl-butanoic acid | 0.00004 | 0.35 |

| 11 | Nonanedioic acid | 0.4 | 0.089 |

NED, no evidence of disease; Within, within recurrence; Post, post recurrence

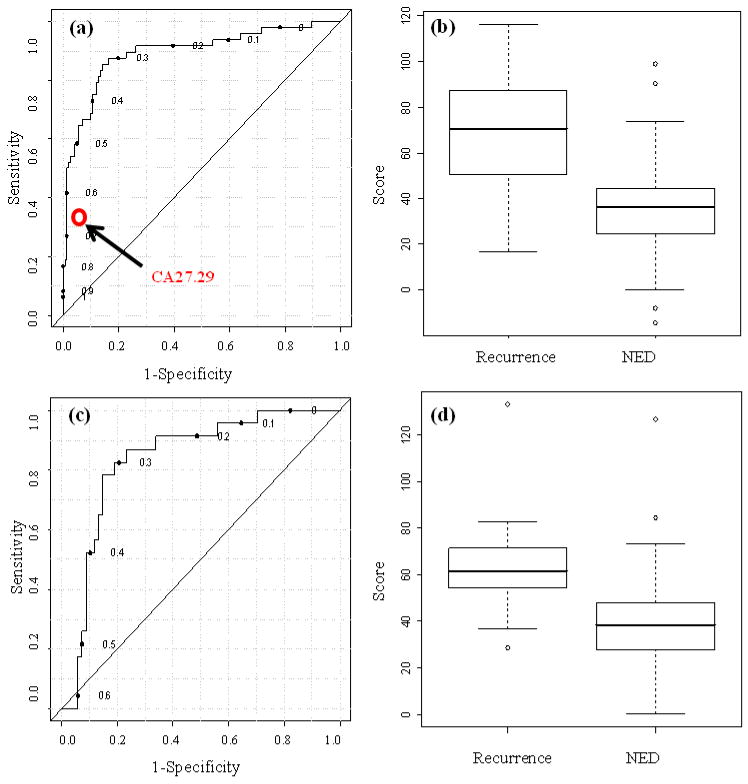

The performance of the 11 metabolite markers in classifying the recurrence of breast cancer was tested both individually and collectively. Box and whisker plots for the individual markers expressed in terms of the relative peak integrals are shown in Fig. 1. The ROC curve for the predictive model derived from PLS-DA analysis using Post and Within vs. NED samples is very good (Fig. 2a), with an AUROC of 0.88, a sensitivity of 86%, and specificity of 84% at the selected cutoff value. Further comparison of the discrimination power of the model between recurrent breast cancer and NED is shown in the box-whisker plots in Fig. 2b, which is drawn using the scores of the model for all Post and Within vs. NED samples. A comparison of the metabolite profiling results with the CA 27.29 IVD data that had been obtained for the same samples is made in Table 3, indicating a large difference in sensitivity.

Figure 1.

Box and whisker plots illustrating the discrimination between Post and Within recurrence versus NED patients for all samples for the 7 NMR and the 4 GCxGC-MS markers. The horizontal line in the mid portion of the box represents the mean while the bottom and top boundaries of the boxes represent 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The lower and upper whiskers represent the 5th and 95th percentiles respectively, while the open circles represent outliers.

Figure 2.

(a) ROC curve generated from the PLS-DA model described in the text using post and within recurrence versus NED, and the performance of CA 27.29 on the same samples; (b) Box and whisker plots for the two sample classes showing discrimination of the Within and Post recurrence from the NED patients using the model predicted scores; (c) ROC curve generated from the PLS-DA prediction model using the testing sample set based on the second statistical approach described in Figure S2; (d) Box and whisker plots for the two sample classes showing discrimination of the post and within recurrence from the (NED) patients using the predicted scores from the testing set.

Table 3.

Comparison of the diagnostic performance of the breast cancer recurrence metabolite profile (BCR) (at cut-off values of 48 and 54) and CA 27.29.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|

| BCR profile 1 | 86% 68% |

84% 94% |

| CA27.29 | 35% | 96% |

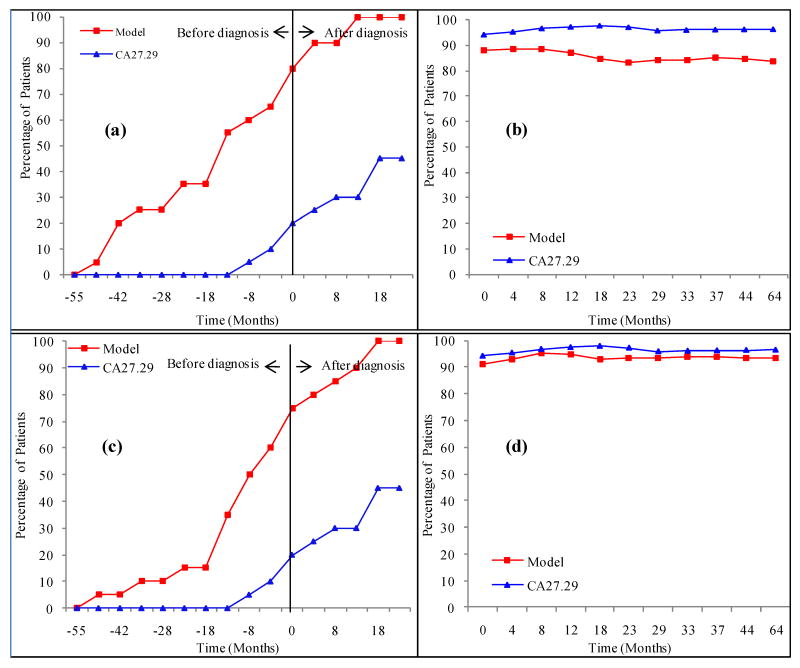

Subsequently, the predictive power of the model for early recurrence detection was evaluated. All samples from recurrent breast cancer patients were grouped together with respect to the time of diagnosis for each patient. Samples within 5 months of one another were grouped, and an average value in months was assigned to each group. The number of months and sign represent the average time at which the samples were collected before (negative time) or after (positive time) the clinical diagnosis. The percentage of patients for which the recurrence was correctly diagnosed was calculated using the model as a function of time is shown in Fig. 3a. For this graph, the first time a patient's score rises above the threshold value of 48, the patient is considered to have recurred. For comparison, the results for the conventional cancer antigen marker, CA 27.29, which were obtained at the time of sample collection, are also shown in Fig. 3a. Here, the recommended cut-off value for CA 27.29 of 37.7 U/mL was used for calculating the clinical sensitivity and specificity for the same set of samples (28). As seen in the figure, for both the metabolite profiling model and CA 27.29, the number of patients correctly diagnosed increases as time progresses. However, at the time of clinical diagnosis, our model based on metabolite profiling detects 75% of the recurring patients, while the CA 27.29 marker detects only 16%. In addition, 55% of the recurrence patients were diagnosed 13 months before they were clinical diagnosed, compared to about 5% for CA 27.29. A similar comparison of the results for NED patients indicate that nearly 90% of the patients were correctly diagnosed as true negatives throughout the period of sample collection and the performance of the metabolite profiling model were comparable to those of CA 27.29 (Fig. 3b), although there was some falling off of the specificity with time. Increasing the threshold value to 54 led to an increase in specificity to about 94% (Fig. 3d) and concomitantly a decrease in sensitivity to 68% (Fig. 3c). The threshold value for 98% specificity was 65 and for 94% sensitivity was 41.

Figure 3.

(a) Percentage of recurrence patients correctly identified using the 11 marker model (red squares) and CA 27.29 (blue triangles) as a function of time for all recurrence patients using a cutoff threshold of 48; (b) Percentage of NED patients correctly identified using the same model (red squares) and CA 27.29 (blue triangles) as a function of time using the same threshold of 48; (c) same information as in (a) but using a threshold of 54; (d) same information as in (b) but using a threshold of 54.

Separately, the model was also tested on the recurrent breast cancer patients based on the stage of the cancer at the initial diagnosis, the type of recurrence, estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) receptors status. The results showed some differences between ER+ and ER- patients and between PR+ and PR- patients (see Fig. 4). While the model for ER+ and PR+ patients was comparable to that when all the samples were tested together (Fig. 3a), nearly 40% of the ER- and PR- patients were detected as early as 28 months before the clinical diagnosis. However, the percentage of ER- and PR- patients detected at a later period remained 10% to 20% lower compared to ER+ and PR+ patients. The performance of the model for initial stage III cancer was slightly better than that for stage II. In addition, the model based on the site of recurrence showed comparable performance for bone and lung cancer, and was slightly better than when all the recurrent patients were tested together (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Percentage of recurrence patients correctly identified based on their (a) estrogen receptor (ER) and (b) progesterone receptor (PR) status as a function of time using the same 11 markers model and a cutoff threshold of 48.

A second statistical analysis based on the model derived from variable selection using a training sample set (see Supplementary Figs. S2 and S5) and predicting the class membership of the samples from an independent sample set (testing set) also provided good performance. The same 11 markers were top ranked by logistic regression, with the exception of nonanedioic acid, which was ranked 13th overall. However, it was included as part of the 11 marker model in this second analysis for consistency and comparison purposes. As shown in Fig. 2c, the testing set of samples yielded an AUROC of 0.84 with a sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 85%. The ROC plot for the testing test thus obtained was also comparable to that obtained by the first statistical analysis (Fig. 2a). Moreover, the average scores for both recurrent breast cancer and NED (Fig, 2d) compared well with those shown in Figs 2b. The difference between the scores for recurrence and NED were highly statistically significant for both training (p-value = 1.40E-05) and testing sets (p-value = 2.25E-04). The results of this second statistical analysis provide evidence that the data set of samples and the metabolite profile derived from our statistical analysis is quite consistent.

Discussion

In this study we present the development of a metabolomics based profile for the early detection of breast cancer recurrence. The investigation makes use of a combination of analytical techniques, NMR and MS, and advanced statistics to identify a group of metabolites that are sensitive to the recurrence of breast cancer. We have shown that the new method distinguishes recurrence from NED patients with significantly improved sensitivity compared to CA 27.29. Using the predictive model, the recurrence in over 55% of the patients was detected as early as 13 months before the recurrence was diagnosed based on the conventional methods.

Breast cancer recurs in over 20% of patients after treatment. Up to nearly 50% improvement in the relative survival of patients can be achieved by detecting at least local recurrence at asymptomatic phase underscoring the need to develop reliable markers indicative of secondary tumor cell proliferation (6). Currently, a number of rapid and non-invasive tests based on circulating tumor markers such as carcinoembryonic antigen and cancer antigens are commercially available. However, the performance of these markers may be too poor to be of significant value for improving early detection because the levels of these markers are also elevated in numerous other malignant and non-malignant conditions unconnected with the breast cancer (29). Considering such limitations, the American Society of Clinical Oncologists (ASCO) guidelines recommend the use of these markers only for monitoring patients with metastatic disease during active therapy in conjunction with numerous other examinations and investigations (30). The results presented here based on the detection of multiple metabolites in the patients' blood provide a new approach for earlier detection.

Although perturbation in the metabolite levels were detected for nearly all the 40 metabolites that were used in the initial analysis (supplementary Table S1), the use of smaller numbers of metabolites provided improved models. Particularly, the group of 11 metabolites (7 from NMR and 4 from GC; Table 2) contributed significantly to distinguishing recurrence from NED. Further, the predictive model derived from these 11 metabolites performed significantly better in terms of both sensitivity and specificity when compared to those derived using individual metabolites or a group of metabolites derived from a single analytical method, NMR or MS, alone (Figs.1 and 2). Evaluation of other models with fewer metabolites indicated that they could also provide useful profiles. The AUROC for an 8 metabolite profile (4 detected by NMR and 4 by GC-MS) was 0.86, while a 7 marker model detected by NMR alone had an AUROC of 0.80. Nevertheless, the model based on 11 metabolites had the best performance and clearly outperformed the accepted monitoring assay CA 27.29 currently used for monitoring patients (Fig. 3). These results promise a significant improvement for early detection and potentially better treatment options for recurring patients.

A number of studies to date have used NMR or MS methods to detect altered metabolic profiles in different types of malignancy owing to the ability of the analytical techniques to analyze a large number of metabolites in a single experiment (16, 20, 21, 31-35). In particular, several investigations have focused on establishing breast cancer biomarkers using metabolomics approach and numerous metabolites including glucose, lactate, lipids, choline and amino acids are shown to correlate with breast cancer (36-42). A sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 82% in the classification of tumor and non-involved tissues was achieved from the analysis of NMR data (37). A majority of these investigations focused on either breast cancer tumors or cell lines and all used NMR methods alone, except for a recent study which utilized a combination of NMR and MS methods (42).

All of the 11 metabolites except 4 (3-hydroxybutyrate, N-acetyl-glycine, 3-hydroxy-2-methyl-butanoic acid and nonanedioic acid) have been identified as breast cancer associated in previous studies (36-42). The 11 serum metabolites represent some of the changes in metabolic activity of several pathways associated with breast cancer, including amino acids metabolism (glutamic acid, histidine, proline and tyrosine), glycolysis (lactate), phospholipid metabolism (choline) and fatty acid metabolism (nonanedioic acid) (Supplementary Fig. S6). Numerous investigations of metabolic aspects of tumorigenesis have shown the association of a majority of these metabolites with breast cancer. For example, studies on breast cancer cells as well as in vivo and ex vivo studies on breast tumors have shown that choline differentiates breast cancer from normal cells or tissue (36, 40, 42, 43). Choline is one most the most prominent metabolites in cell biology and is invariably associated with increased activity of tumor cell proliferation in breast cancer. Increased lactate is one of the early findings of metabolic changes reported for breast tumors. Similarly, association of a number of amino acids, fatty acids and organic acids with breast cancer has been established earlier (39, 40, 44). As shown in Fig. 1, the mean concentrations for a number of these metabolites including formate, histidine, proline, N-acetyl-glycine and 3-hydroxy-2-methyl-butanoic acid decrease significantly in recurrent cancer. Numerous studies report decrease in amino acid levels in the plasma of patients with malignant tumors (44). Increased demand for amino acids in the presence of a tumor is thought to be one of the reasons for this decrease. It is inferred based on numerous independent investigations between 1978 and 2003 that the metabolic profile specifically of free amino acids can differ between early stage and late stage cancer. It is thus not too surprising then that the selection of such metabolites can be used in part to develop a sensitive predictive model to distinguish recurrence from NED patients. We also note that the increase in tyrosine has been observed in two liver cancer studies (45-46).

Correlation of the metabolites with clinical parameters such as the cancer stage and, estrogen and progesterone receptor status contributes to the extent by which the disease can be detected early. Recently, a link between tumor metabolites and, estrogen and progesterone receptor status was shown with a prediction accuracy of 88% and 78%, respectively indicating the metabolic profile does vary with estrogen and progesterone receptor status of the patient (31). These results support our observations and suggest that inclusion of such parameters may help advance further development of early detection metabolite profiles.

In conclusion, we present the development of a new tool for the surveillance of breast cancer recurrence based on the metabolic profiling of blood samples from patients obtained serially. The performance of the model was optimal when metabolites detected by both NMR and MS were combined. This multiple metabolite model outperforms the current diagnostic methods employed for breast cancer patients, including the tumor marker CA 27.29 for which comparison data on the same samples was available for direct comparison. Metabolic profiling of blood serum by NMR and mass spectroscopy can detect breast cancer relapse before it occurs, opening a window of opportunity for patients and oncologists to improve treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by the NIH (NIGMS R01GM085291-02 and R25CA128770, Cancer Prevention Internship Program), the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research, the Purdue Research Foundation, and the Oncological Sciences Center in Discover Park at Purdue University. Partial funding for this work from Matrix-Bio, Inc. is also appreciated. Third Nerve, LLC provided access to specimen materials and data through its ongoing survey study of both new and established cancer markers. The authors acknowledge Heather Heiligstedt for her help in constructing the pathway diagram (Supplementary Fig. S6).

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts and Figures 2009–2010. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brewster AM, Hortobagyi GN, Broglio KR, et al. Residual risk of breast cancer recurrence 5 years after adjuvant therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1179–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Megha T, Neri A, Malagnino V, et al. Traditional and new prognosticators in breast cancer: Nottingham index, Mib-1 and estrogen receptor signaling remain the best predictors of relapse and survival in a series of 289 cases. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:266–73. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.4.10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu WL, Jansen L, Post WJ, Bonnema J, Van de Velde JC, De Bock GH. Impact on survival of early detection of isolated breast recurrences after the primary treatment for breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;14:403–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houssami N, Ciatto S, Martinelli F, Bonardi R, Duffy SW. Early detection of second breast cancers improves prognosis in breast cancer survivors. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1505–10. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pivot X, Asmar L, Hortobagyi GN, Theriault R, Pastorini F, Buzdar A. A Retrospective Study of First Indicators of Breast Cancer Recurrence. Oncology. 2000;58:185–90. doi: 10.1159/000012098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebeling FG, Stieber P, Untch M, et al. Serum CEA and CA 15-3 as prognostic factors in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1217–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhafir A, Gabrielle K, Eddie M, et al. CA 15-3 is predictive of response and disease recurrence following treatment in locally advanced breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gion M, Mione R, Leon AE, Dittadi R. Comparison of the Diagnostic Accuracy of CA 27.29 and CA15.3 in Primary Breast Cancer. Clin Chem. 1999;45:630–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duffy MJ. Serum Tumor Markers in Breast Cancer: Are They of Clinical Value? Clin Chem. 2006;52:345–51. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.059832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lumachi F, Basso SMM, Basso U. Breast Cancer Recurrence: Role of Serum Tumor Markers CEA and CA 15-3 In Hayat MA, editor Methods of Cancer Diagnosis, Therapy and Prognosis. Netherlands: Springer; 2008. pp. 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lumachi F, Ermani M, Brandes AA, Basso S, Basso U, Boccagni P. Predictive value of different prognostic factors in breast cancer recurrences: Multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model. Anticancer Res. 2001;6:4105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholson JK, Lindon JC, Holmes E. ‘Metabonomics’: understanding the metabolic responses of living systems to pathophysiological stimuli via multivariate statistical analysis of biological NMR spectroscopic data. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:1181–9. doi: 10.1080/004982599238047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odunsi K, Wollman RM, Ambrosone CB, et al. Detection of epithelial ovarian cancer using 1H-NMR-based metabonomics. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:782–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gowda GAN, Zhang S, Gu H, Asiago V, Shanaiah N, Raftery D. Metabolomics-Based Methods for Early Disease Diagnostics: A Review. Expert Rev Mol Diagnos. 2008;8:617–33. doi: 10.1586/14737159.8.5.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan Z, Raftery D. Combining NMR Spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometery in Metabolomics. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;387:525–7. doi: 10.1007/s00216-006-0687-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmes E, Wilson ID, Nicholson JK. Metabolic phenotyping in health and disease. Cell. 2008;134:714–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clayton TA, Lindon JC, Cloarec O, et al. Pharmaco-metabonomic phenotyping and personalized drug treatment. Nature. 2006;440:1073–7. doi: 10.1038/nature04648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denkert C, Budczies J, Kind T, et al. Mass spectrometry-based metabolic profiling reveals different metabolite patterns in invasive ovarian carcinomas and ovarian borderline tumors. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10795–804. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sreekumar A, Poisson LM, Rajendiran TM, et al. Metabolomic profiles delineate potential role for sarcosine in prostate cancer progression. Nature. 2009;457:910–4. doi: 10.1038/nature07762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 22.Shanaiah N, Zhang S, Desilva MA, Raftery D. NMR-Based Metabolomics for Biomarker Discovery. In: Wang F, editor. Methods in Pharmacology and Toxicology: Biomarker Methods in Drug Discovery and Development. Humana Press; Totowa NJ: 2008. pp. 341–68. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1751-0473-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kiezun A, Lee ITA, Shomron N. Evaluation of optimization techniques for variable selection in logistic regression applied to diagnosis of myocardial infarction. Bioinformation. 2009;3:311–3. doi: 10.6026/97320630003311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen MH, Dey DK. Variable selection for multivariate logistic regression models. J Statist Plann Inference. 2003;111:37–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Markley JL, Anderson ME, Cui Q, et al. New bioinformatics resources for metabolomics. Pacific Symp Biocomp. 2007;12:157–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wishart DS, Tzur D, Knox C, et al. HMDB: The Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D521–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan DW, Beveridge RA, Muss H, et al. Use of Truquant BR radioimmunoassay for early detection of breast cancer recurrence in patients with stage II and stage III disease. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2322–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheung KL, Graves CR, Robertson JF. Tumor marker measurements in the diagnosis and monitoring of breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;26:91–102. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.1999.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5287–312. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Giskeødegård GF, Grinde MT, Sitter B, et al. Multivariate modeling and prediction of breast cancer prognostic factors using MR metabolomics. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:972–9. doi: 10.1021/pr9008783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griffin JL, Lehtimaki KK, Valonen PK, et al. Assignment of 1H nuclear magnetic resonance visible polyunsaturated fatty acids in BT4C gliomas undergoing ganciclovir-thymidine kinase gene therapy-induced programmed cell death. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hakumaki JM, Poptani H, Puumalainen AM, et al. Quantitative 1H nuclear magnetic resonance diffusion spectroscopy of BT4C rat glioma during thymidine kinase-mediated gene therapy in vivo : identification of apoptotic response. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3791–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffiths JR, McSheehy PM, Robinson SP, et al. Metabolic changes detected by in vivo magnetic resonance studies of HEPA-1 wild-type tumors and tumors deficient in hypoxia-inducible factor-1h (HIF-1h): evidence of an anabolic role for the HIF-1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2002;62:688–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Florian CL, Preece NE, Bhakoo KK, Williams SR, Noble MD. Cell type-specific fingerprinting of meningioma and meningeal cells by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Cancer Res. 1995;55:420–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gribbestad IS, Sitter B, Lundgren S, Krane J, Axelson D. Metabolite composition in breast tumors examined by proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Anticancer Res. 1999;19:1737–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sitter B, Lundgren S, Bathen TF, Halgunset J, Fjosne HE, Gribbestad IS. Comparison of HR MAS MR spectroscopic profiles of breast cancer tissue with clinical parameters. NMR Biomed. 2006;19:30–40. doi: 10.1002/nbm.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sitter B, Sonnewald U, Spraul M, Fjösne HE, Gribbestad IS. High-resolution magic angle spinning MRS of breast cancer tissue. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:327–37. doi: 10.1002/nbm.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitehead TL, Kieber-Emmons T. Applying in vitro NMR spectroscopy and 1H NMR metabonomics to breast cancer characterization and detection. Prog NMR Spectrosc. 2005;47:165–74. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng LL, Chang IW, Smith BL, Gonzalez RG. Evaluating human breast ductal carcinomas with high-resolution magic-angle spinning proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1998;35:194–202. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bathen TF, Jensen LR, Sitter B, et al. MR-determined metabolic phenotype of breast cancer in prediction of lymphatic spread, grade, and hormone status. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;104:181–9. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9400-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang C, Richardson AD, Smith JW, Osterman A. Comparative metabolomics of breast cancer. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2007;12:181–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gribbestad IS, Singstad TE, Nilsen G, et al. In vivo 1H MRS of normal breast and breast tumors using a dedicated double breast coil. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:1191–7. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880080602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lai HS, Lee JC, Lee PH, Wang ST, Chen WJ. Plasma free amino acid profile in cancer patients. Semin Cancer Biol. 2005;15:267–76. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wanatabe A, Higashi T, Sakata T, Nagashima H. Serum amino acid levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1984;54:1875–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841101)54:9<1875::aid-cncr2820540918>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubota A, Meguid MM, Hitch DC. Amino acid profiles correlate diagnostically with organ site in three kinds of malignant tumors. Cancer. 1992;69:2343–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920501)69:9<2343::aid-cncr2820690924>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.