Abstract

Background

Women with heart disease have adverse psychosocial profiles and poor attendance in cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs. Few studies examine CR programs tailored for women for improving their quality of life (QOL).

Methods

This randomized clinical trial (RCT) compared QOL among women in a traditional CR program with that of women completing a tailored program that included motivational interviewing guided by the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of behavior change. Two measures of QOL, the Multiple Discrepancies Theory questionnaire (MDT) and the Self-Anchoring Striving Scale (SASS), were administered to 225 women at baseline, postintervention, and 6-month follow-up. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to compare changes in QOL scores over time.

Results

Baseline MDT and SASS scores were 35.1 and 35.5 and 7.1 and 7.0 for the tailored and traditional CR groups, respectively. Postintervention, MDT and SASS scores increased to 37.9 and 7.9, respectively, for the tailored group compared with 35.9 and 7.1 for the traditional group. Follow-up scores were 37.7 and 7.6 for the tailored group and 35.7 and 7.1 for the traditional group. Significant group by time interactions were found. Subsequent tests revealed that MDT and SASS scores for the traditional group did not differ over time. The tailored group showed significantly increased MDT and SASS scores from baseline to posttest, and despite slight attenuation from posttest to 6-month follow-up, MDT and SASS scores remained higher than baseline.

Conclusions

The CR program tailored for women significantly improved global QOL compared with traditional CR. Future studies should explore the mechanisms by which such programs affect QOL.

Introduction

In the current climate of evidence-based medicine, healthcare researchers are justifiably concerned with providing evidence not only that their interventions positively influence morbidity and mortality but also that survival translates into improved, or at least not deteriorated, quality of life (QOL). Given the increased longevity that current medical advances afford, QOL becomes ever more important as a crucial outcome. For more than a decade, Beckie et al.1–3 have conceptualized QOL as a global personal assessment of a single dimension that may be responsive to a variety of other distinct dimensions, including dimensions of health. Social psychologists have long conceived of global QOL as the satisfaction of individual needs that are determined by the perceived discrepancy between aspirations and achievements.4,5 Influenced by their work, Michalos6 developed the Multiple Discrepancies Theory (MDT), with the basic premise that a close match between actual life conditions and aspirations leads to a perceived QOL that is higher than when a large gap exists. This perspective permits study of the extent to which not only changes in health but also changes in psychosocial and economic status contribute to QOL.

Studies demonstrating weak causal relationships between health perceptions and global QOL1,2,7 have arguably resulted in the advent of the construct health-related quality of life (HRQOL), which, as expected, is more responsive to healthcare interventions than is global QOL. Individuals have unique life circumstances, resources, and constraints that shape their global QOL assessments. Although the terms QOL and HRQOL are often used interchangeably, previous research has found that the QOL of women with coronary heart disease (CHD) is poorer than that in men.8–11

Beckie and Hayduk2 evaluated the global QOL and perceptions of health of 46 women and 260 men 12 weeks after coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. The study showed that the participants viewed QOL as a global cognitive judgment about their life that was influenced only modestly by their perceived health. Our subsequent research examined the influence of perceived health on global QOL in women with CHD.1 Women's outlook on life (e.g., hope and optimism) was nearly as important as their health perceptions in determining their global QOL. This finding suggests that tailoring cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programs to be inclusive of women's psychosocial needs could potentially improve their QOL.

The leading cause of death of American women is CHD.12 CR programs yield compelling morbidity and mortality benefits13,14 and improved psychosocial well-being14–19 and perceived health status.20 Despite these benefits and international endorsements of CR as a model for secondary prevention,17,21,22 only 15%–20% of eligible women use these programs.23–30 Physician referral and endorsement are an acknowledged powerful predictor of CR participation,31–36 but suboptimal referrals of women are compounded by various patient-oriented, provider-oriented, and programmatic factors.25,26,37–39 Particularly underrepresented in CR are elderly women, obese women, nonwhite women, and those with greater comorbidity, lower exercise capacity, less social support, competing family obligations, and incomplete medical insurance coverage.25,27,28,40 Compared with men, women are at a 2-fold increased risk of noncompletion of CR.16 Evidence for a dose-response relationship between attendance rates and subsequent mortality after CR completion19 intensifies the urgency to remedy the poor completion rates among women.

Women with CHD not only manifest particularly adverse psychosocial profiles and suboptimal social support but also report unique gender-specific CR preferences and needs.41,42 Recognition of unique gender-based psychosocial issues potentially affecting QOL has motivated recommendations for efficacious CR programs designed for women.43,44 Although some bemoan the lack of gender-tailored risk reduction approaches for women,45 others have advanced the concept of gender-specific tailoring in CR programs.46,47 Davidson et al.47 conducted a pilot study of an 8-week CR program tailored to the psychological and social needs of 54 women with CHD. They failed to find significant changes in psychosocial variables of the 48 women who completed this study, but qualitative data revealed unique problems women face after an acute cardiac event that could be addressed in gender-focused CR programs.

The current study was undertaken to address the underrepresentation of women in cardiovascular clinical trials,48 the higher mortality and complication rates in women after acute coronary syndromes compared with men,49 and the recognized need to redesign CR programs to respond to the unique psychosocial needs of women26 and to enhance their global QOL. Examining the impact of CR interventions for women is warranted in light of their adverse psychosocial profiles and their poor completion rates. This study sought to extend previous research by examining the effects of a modified CR program for women (hereafter referred to as “tailored”) compared with traditional CR for improving QOL. The specific aim addressed here was to examine the effects of a tailored CR intervention compared with traditional CR for improving QOL in women with CHD. We hypothesized that women completing the tailored CR program would demonstrate greater improvements in QOL compared with women completing traditional CR and that these improvements would be sustained to a greater degree by the 6-month follow-up.

Materials and Methods

This two-group randomized clinical trial (RCT) examined physiological (e.g., weight, lipid profile, cardiorespiratory fitness) and psychosocial (e.g., anxiety, perceptions of health, social support) outcomes among women completing a traditional CR program compared to women completing a tailored program guided by the Transtheoretical Model (TTM) of behavior change delivered using motivational interviewing therapeutic methods. Details of the recruitment procedures, the interventions, and attendance are described elsewhere50–52 and summarized below. The Institutional Review Boards of the university and the participating hospital approved the study protocol.

Participants, assessment, and randomization

Between January 2004 and March 2008, participants were recruited from those referred to an outpatient CR program in Florida. Automatic physician orders in one community hospital were the primary referral mechanisms. The inclusion criteria were women >21 years (1) diagnosed with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI), angina, or having undergone CABG surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) within the last year and (2) able to read, write, and speak English. The exclusion criteria were (1) health insurance coverage for <36 electrocardiogram-monitored exercise sessions, (2) cognitive impairment, and (3) inability to ambulate. Upon receipt of the physician referral to CR, the study recruiter screened women for study eligibility and conducted individualized orientations for eligible women. The trained research assistant conducted the comprehensive evaluation and collected all baseline data after consent signing and before randomization. The statistician provided computer-generated random treatment allocation sequences that were placed in opaque envelopes, sealed, and delivered to the project director, who opened the sealed envelope to reveal the group assignment. A biased coin randomization algorithm53,54 was used to ensure balance between the interventions across time to accommodate a maximum of 8 electrocardiogram monitoring units per group. Outcome data were collected 1 week and 6 months after completion of CR by the same research assistant masked to group assignment.

Interventions

Traditional intervention

The traditional CR program, nationally certified by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, was supervised by female nurses and exercise physiologists using a case management model. Monitored aerobic exercise and resistance training occurred 3 days per week for 12 weeks. Exercise began with a 5-minute warm-up, followed by 35–45 minutes of aerobic exercise with exercise heart rates maintained at 60%–85% of maximal heart rate calculated from the baseline exercise tolerance test. Resistance training using wall pulleys and hand weights was followed by 5 minutes of cool-down exercises. Group participants could attend any scheduled mixed-gender exercise session between 8 am and 4 pm. They were also free to attend CHD risk factor modification education sessions offered on eight consecutive Mondays repeated five times throughout the day.

Tailored intervention

This exercise protocol was similar to the traditional CR intervention, although participants exercised exclusively with women. To minimize crossover contamination, exercise was conducted during one time slot when the CR facility was closed to other patients and staff. The intervention, guided by the principles of TTM55 and motivational interviewing,56 was administered by research nurses and exercise physiologists. At baseline, 13 weeks, and 37 weeks, women were assessed for their stage of motivational readiness to change healthy eating, physical activity, and stress management. The TTM expert system assessment57 developed by Pro-Change Behavior Systems™ generated an individualized report tailored on TTM constructs. Baseline reports provided normative feedback on current stage of change, decision balance, self-efficacy, and processes of change. Participants received follow-up reports, with normative and ipsative (e.g., compared to self at baseline) feedback on TTM constructs being applied appropriately for each behavior and recommendations for stage-specific strategies to assist them with motivational stage progression.

A clinical psychologist or a clinical nurse specialist (CNS), formally trained in motivational interviewing, conducted 60-minute individualized psychotherapeutic sessions at weeks 1, 6, and 12. The efficacy of motivational interviewing is based on the spirit of collaboration rather than prescription, evoking rather than instilling intrinsic motivation and honoring autonomy to choose.58 Change talk, the individual's verbalized arguments for change, is deemed integral to inducing commitment to change. There is robust evidence for the predictive ability of change talk for improving outcomes.59,60 The CNS and psychologist facilitated psychoeducational sessions on 10 consecutive Wednesdays focused on gender-based practice guidelines, relaxation exercises, and social support.

Quality of life measures

QOL was assessed using the MDT questionnaire6,61 and the Self-Anchoring Striving Scale (SASS).4 The MDT questionnaire has 8 items that evaluate perceived discrepancies between one's current QOL and a set of internal standards. These discrepancies are between what one has and wants, relevant others have, the best one has had in the past, expected to have 3 years ago, expects to have after 5 years, deserves, and needs. The first item of the MDT, the Life-as-a-Whole item asks: How do you feel about your life as a whole right now? The response categories are (1) terrible, (2) very dissatisfying, (3) dissatisfying, (4) mixed, (5) satisfying, (6) very satisfying, and (7) delightful. The 8 items are summed for a total score that can range from 8 to 56. The instrument has been used with women and men with CHD and with community participants.1,2,61 Cronbach's alpha for the MDT in the current study at all three time points was 0.89 or higher.

The SASS is a single item depicted as a ladder using only numbers as descriptors of the rungs of the ladder.4 The respondent is shown the ladder and asked: Where on the ladder would you place your present life? The base of the ladder is illustrated with a zero and labeled, the worst you can imagine. The successive rungs are sequentially numbered, and the top rung is labeled, 10, the best you can imagine. Participants respond by circling the appropriate ladder rung with the response anchored within their own reality.4 The SASS has been used in studies of men and women with CHD and in CR settings.1–3,62,63 These QOL measures were selected because they are used in both healthcare and social/psychological research and because each measure provides a global evaluation of one's life. They are consistent with conceptualization of QOL as a global personal assessment of a single dimension, which may be causally responsive to a variety of other distinct dimensions, including dimensions such as health.1–3

Physiological measures

Blood pressure was measured with one calibrated automated monitor (Datascope, Mahwah, NJ) according to established guidelines.64 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). Body fat composition was determined using skinfold measurements taken at three sites (suprailium, triceps, and thigh), and percentage of body fat was calculated from standardized tables.65 Lipid profiles and serum glucose were measured after a 12-hour fast using the Cholestech LDX System. Using the modified Bruce protocol for the symptom limited exercise tolerance test exercise capacity was expressed in units of metabolic equivalents.66 Urine cotinine was used to measure exposure to nicotine. Specimens were screened by immunoassay at a threshold level of 25 ng/mL cotinine. If positive, it was confirmed by gas chromatography (MedTox Laboratories, St. Paul, MN).

Attendance measures

Exercise attendance, recorded at each session for hospital billing purposes, was calculated as the number of sessions attended out of a possible 36 prescribed sessions. Education attendance was expressed as a percentage of the number of sessions completed because the tailored intervention comprised 10 and the traditional intervention consisted of 8 education sessions.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 17, for Windows (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations (SD), correlations, and percentages. Primary analyses of QOL change are based on intent-to-treat principals. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess changes in QOL scores among the 225 women with complete data at all three time points. All tests were 2-tailed and evaluated for statistical significance using an α criterion of 0.05.

Results

Participants

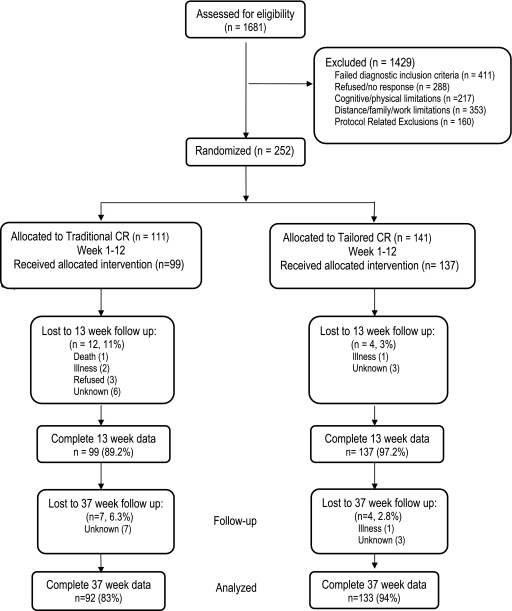

A total of 252 women were randomly allocated to either the traditional CR or the tailored CR program, with 225 women providing complete QOL scores at all data collection points. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants through each stage of the study. Baseline demographic characteristics were not different in the randomized groups (Table 1). The mean age was 63 years (SD 12, range 31–87 years), and most women were white (82%), married (53%), retired (47%), and with ≥ a high school education (92%). Fifty percent of participants had undergone a PCI, and 33.7% had CABG surgery; fewer were treated medically for stable angina (11%) or an MI (5%). Baseline consumption of evidence-based cardiovascular medications did not differ between those in traditional CR and those in the tailored group. Participants were not different on measures of obesity, lipid profiles, or blood pressure (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Flow of study participants, January 2004–March 2008.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Randomization Group

| Characteristica,b | Traditional CR n = 92 | Tailored CR n = 133 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 64 ± 11 | 63 ± 11 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 56 (61) | 94 (71) |

| African American | 17 (18) | 20 (15) |

| Hispanic | 18 (20) | 18 (14) |

| Asian | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 38 (41) | 57 (43) |

| Some college | 40 (43) | 44 (33) |

| Baccalaureate degree | 8 (9) | 23 (17) |

| Graduate degree | 6 (7) | 9 (7) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 50 (54) | 73 (55) |

| Divorced/separated | 20 (22) | 29 (22) |

| Widowed | 15 (16) | 26 (20) |

| Single, never married | 7 (8) | 5 (4) |

| Work status | ||

| Retired | 48 (52) | 66 (50) |

| Full-time/part-time | 28 (30) | 35 (26) |

| Disabled/unemployed | 16 (17) | 32 (24) |

| Diagnostic eligibility for cardiac rehabilitation | ||

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 39 (42) | 74 (56) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft surgery | 37 (40) | 39 (29) |

| Stable angina | 12 (13) | 13 (10) |

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (4) | 7 (5) |

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables are presented as number and (%).

Chi-square test and t test for discrete and continuous variables, respectively, p > 0.05 for all comparisons of characteristics between groups.

CR, cardiac rehabilitation; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics by Randomization Group

| Characteristica | Traditional CR n = 92 | Tailored CR n = 133 |

|---|---|---|

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 130 ± 17 | 125 ± 19 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 73 ± 11 | 71 ± 10 |

| Resting heart rate, bpm | 71 ± 10 | 71 ± 11 |

| HDL-C, mg/dLb | 44 ± 14 | 46 ± 14 |

| LDL-C, mg/dL | 91 ± 33 | 87 ± 32 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 161 ± 78 | 146 ± 74 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 106 ± 31 | 109 ± 32 |

| Percent body fat | 37 ± 6 | 37 ± 6 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31 ± 7 | 31 ± 7 |

| Weight, pounds | 179 ± 41 | 180 ± 43 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 100 ± 15 | 100 ± 16 |

| Pack years smoked | 16 ± 22 | 18 ± 25 |

| Urine cotinine, ng/mL | 159 ± 383 | 102 ± 255 |

| Peak exercise capacity, METS | 5 ± 2 | 6 ± 3 |

| Peak treadmill time, minutes | 8 ± 3 | 8 ± 4 |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| Statins | 83 (90) | 117 (88) |

| Beta-blockers | 77 (84) | 108 (81) |

| Aspirin | 81 (88) | 112 (84) |

| Clopidogrel | 53 (58) | 89 (67)c |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 27 (29) | 58 (44)c |

| Antidepressant | 16 (17) | 31 (23) |

| Anxyolytic | 26 (28) | 18 (14) |

Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation; categorical variables are number (%).

To convert LDL and HDL to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259; to convert triglycerides to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0113; to convert glucose to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0555.

Chi-square test and t test for discrete and continuous variables, respectively, p < 0.05.

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; METS, metabolic equivalents.

Quality of life scores by intervention group

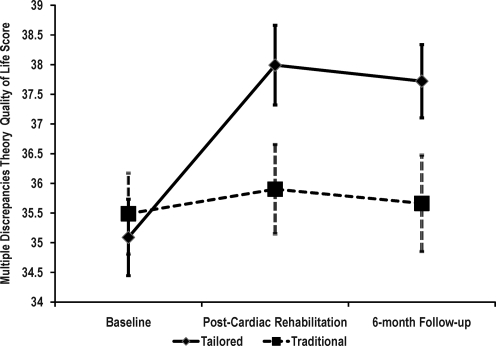

At baseline, mean MDT scores were 35.1 and 35.5 for the tailored and traditional CR groups, respectively. Post-CR mean scores increased to 37.9 for the tailored group and 35.9 in the traditional CR group (Fig. 2). At the 6-month follow-up, these scores were 37.7 for the tailored group and 35.7 for the traditional CR group. A significant group by time interaction showed that changes in MDT scores were different for the two groups (F(2, 446) = 5.94, p = 0.003, eta2 = 0.026). Follow-up tests revealed that the mean scores for the traditional group did not differ over time (F(2, 446) = 0.21, p = 0.809, eta2 = 0.001). By contrast, the tailored group showed significant change over time (F(2,446) = 18.31, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.076). Detailed tests on this group showed a significant increase in MDT scores from baseline to post-CR (F(1, 223) = 30.645, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.121), and despite the slight decrease from post-CR to the 6-month follow-up, MDT scores remained significantly higher than baseline (F(1,223) = 23.187, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.094).

FIG. 2.

Multiple Discrepancies Theory (MDT) quality of life scores by intervention group. Data shown as means (standard error). Group by time interaction: F(2,466) = 5.94, p = 0.003.

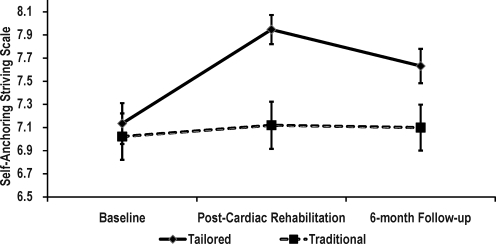

The SASS scores were 7.1 and 7.0 for the tailored and traditional CR groups, respectively at baseline (Fig. 3). Post-CR SASS scores were 7.9 for the tailored group and 7.1 for the traditional CR group. Six months later, these scores were 7.6 for the tailored group and 7.1 for the traditional CR group. A significant group by time interaction revealed that changes in SASS were different for the groups (F(2, 446) = 4.31, p = 0.014, eta2 = 0.019). Follow-up analyses showed that the mean scores for the traditional group were unchanged over time (F(2, 446) = 0.20, p = 0.815, eta2 = 0.001). In contrast, the tailored group showed significant changes over time (F(2,446) = 13.82, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.058). Again, detailed tests showed a significant increase in SASS scores from baseline to post-CR (F(1, 223) = 24.617, p < 0.001, eta2 = 0.099), and even with a slight attenuation from post-CR to the 6-month follow-up, SASS scores remained higher than baseline (F(1, 223) = 10.002, p = 0.002, eta2 = 0.043).

FIG. 3.

Self-Anchoring Striving Scale (SASS) scores by intervention group. Data shown as means (standard error). Group by time interaction: F(2,466) = 4.31, p = 0.014.

Supplemental analyses to address the potential confounding influence of attendance on the QOL scores were conducted using multiple regression analyses. Traditional group participants attended a mean of 30 ± 10 of the 36 prescribed exercise sessions compared with 34 ± 7.6 for the tailored group participants (F(1, 223) = 7.322, p = 0.007). The mean percent attendance at the education sessions was also greater in the tailored group (89 ± 21) than in the traditional group (62 ± 30) (F(1, 223) = 63.843, p < 0.001). Eleven percent (n = 12) of the traditional group compared with 3% (n = 4) of the tailored group failed to complete the post-CR assessment. Participants not completing the 6-month assessment included 2.8% (n = 4) of the tailored compared with 6.3% (n = 7) of traditional CR participants. Baseline QOL scores for the 27 women not completing the study were significantly lower than for those who did [MDT scores 30.44 ± 7.7 vs. 35.25 ± 7.1 (F(1, 250) = 10.940, p = 0.001); SASS scores 5.9 ± 2.1 vs. 7.1 ± 1.9 (F(1, 250) = 8.151, p = 0.005)]. Among the 27 women who failed to complete the study, there were no between-group differences on QOL. Controlling for baseline QOL scores and attendance, the influence of group assignment on the MDT scores (β = 2.811, t = 3.114, p = 0.002) and the SASS scores (β = 0.722, t = 3.097, p = 0.002) remained significant post-CR.

Discussion

The primary finding was a greater improvement in global QOL among women completing a tailored CR program compared with those completing traditional CR. Improved QOL scores were sustained at the 6-month follow-up in the tailored group, whereas those in traditional CR were essentially unchanged over time. These effects remained while controlling for group differences in education and exercise attendance, suggesting that mechanisms other than, or in addition to, exercise and education likely accounted for the observed improvements in QOL in the tailored group. A qualitative distinction between the two interventions is a plausible explanation as a mechanism underlying the differences in outcomes. This study contributes to the state of the science regarding secondary prevention for women, as it represents the first RCT to examine the effects of a CR intervention tailored for women on QOL outcomes.

Cardiac rehabilitation attendance and study completion rates for women in the current study were also better than previously reported. Suaya et al.13 found that among >600,000 Medicare beneficiaries, only 12.2% received one or more CR session, and CR users received a mean of 24 ± 12.4 sessions. Higher-dose CR users demonstrated lower 5-year mortality than lower-dose users. These mortality reductions with more sessions represented a relative reduction of 58% at 1 year and 19% at 5 years. The mortality reductions increased progressively with older age and were greater in women than in men in each age group. To further characterize the dose-response relationship between CR session attendance and long-term outcomes, researchers found that among >30,000 Medicare patients, those who attended 36 sessions, compared with those who attended only 1 session, had a 58% lower risk of death and a 31% lower risk of an MI 4 years after program completion.19 Reportedly, only 18% of patients attended the full 36 sessions that Medicare reimburses. Sanderson et al.67 found that of 526 patients (35% women) in their observational study, 31% of women completed CR compared with 58% of the entire sample. Of those not completing CR, 63% were for personal and 37% for medical reasons. Patients in the nonmedical dropout group attended only 37% of prescribed sessions. Dunlay et al.27 found that of 179 patients enrolled in CR, 64% completed with a mean attendance of 13.5 ± 8.2 sessions, 25% attended ≥ 20 sessions, and 25% attended ≤ 5 sessions. They also reported that more women than men expressed a desire for activities to be separated by gender. Finally, the effects of a secondary prevention trial for women with CHD were assessed 6 weeks and 6 months after the intervention68; they obtained outcomes for 86% of patients at 6 weeks and 80% at 6 months.

Comparing our QOL findings with previous studies in the CR setting was challenging because most studies use observational designs that either include few women or fail to provide gender-specific data. Although statistically significant between-group differences were found in global QOL outcomes (about a 2-point difference in post-CR MDT scores), the conundrum faced is in attempting to infer clinical significance. The greatest impediment to synthesizing the research of the effects of CR on QOL is the diversity of instruments used to measure QOL. The plethora of measures impairs the capacity to establish criteria for clinically significant QOL treatment effects. Kaul and Diamond69 argue that practical significance must be judged in the context of the seriousness of the outcome and the benefit-risk-cost profile.

Investigators of the Enhanced Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) trial62,70 evaluated the effects of a psychosocial intervention compared with usual care for a subset of 2481 post-MI patients (n = 1296, 43% women) on QOL. The ENRICHD trial was a large, randomized trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy among patients with depression or low social support or both. Although that intervention was not effective in reducing risk of reinfarction or death, global QOL assessments using Cantril's ladder at a 6-month follow-up showed a statistically significant 0.3-point difference favoring the intervention group. Although subjective measures, such as QOL, lack the more familiar benchmark values for assessing clinically meaningful change, ENRICHD trial investigators characterized a 0.3-point difference on the SASS as a moderate effect. In the current study, we found an effect over 2 times larger (0.8).

Global QOL outcomes were also examined for 207 patients (26% women) randomized to either a problem-based learning (PBL) CR or a traditional program.63 In addition to usual care, participants in the PBL program attended 13 group sessions focused on individual learning needs and behavioral changes over a year. Median global QOL scores of 8 on the ladder scale in each group after the intervention were reported, with no statistically significant between-group differences. Both the traditional and the PBL programs improved scores by 1 point from baseline. The authors suggested that the global QOL assessment allowed patients to choose aspects of particular personal relevance and integrate these into their conception of their best possible life.

Our study adds an element of clarity to the CR outcomes literature by assessing both global QOL and other concepts amenable to change that determine QOL. Beginning with the premise that women with CHD have unique needs, expectations, priorities, and life challenges, we conceptualized QOL as a global construct that is both responsive to intervention and plausibly influenced by other variables, such as social support and perceived health. We sought to determine the effects of a multicomponent behavioral intervention on overall QOL conceptualized as a global evaluation of one's life. This conceptualization proved sensitive as a subjective outcome when comparing two methods of delivering CR to women. The tailored intervention positively influenced QOL as defined by participants' life circumstances and expectations. Women with CHD may be better served by first identifying the important psychosocial and physiological variables that influence their QOL using psychometrically sound instruments and then tailoring CR interventions to improve the quality of their lives.

Limitations

Caution is warranted in generalizing these results because participants were predominantly Caucasian women from a single institution in the southeastern United States. Also, it is not possible to know if treatment effects observed would persist beyond 6 months. Finally, examining the efficacy of a bundled program such as ours is difficult; we cannot say which components had the greatest influence on global QOL. That the intervention used motivational interviewing, TTM tailoring, gender-specific exercise, education, and social support may have synergistically led to improved global QOL.

Conclusions

This RCT showed that a tailored CR intervention designed for women improved global QOL. Improving QOL may positively influence adherence to healthy behaviors, and assessing QOL early may aid in targeting women for specialized interventions, additional social support, or counseling. Additional research is needed to determine the relative contributions of social support, motivational interviewing, and stage-of-change matching for enhancing QOL in women. Using the principles of comparative effectiveness research,71 CR interventions tailored for women ought to be evaluated in more culturally diverse samples and in broader clinical contexts.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research (R01 NR007678).

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Beckie TM. Beckstead JW. Webb MS. Modeling women's quality of life after cardiac events. West J Nurs Res. 2001;23:179–194. doi: 10.1177/019394590102300206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckie TM. Hayduk LA. Using perceived health to test the construct-related validity of global quality of life. Soc Indicators Res. 2004;65:279–298. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckie T. Hayduk L. Measuring quality of life. Soc Indicators Res. 1997;42:21–39. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantril H. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1965. The pattern of human concerns. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews FM. Withey SB. New York: Plenum Press; 1976. Social indicators of well-being: Americans' perceptions of life quality. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michalos AC. Multiple Discrepancies Theory (MDT) Soc Indicators Res. 1985;16:347–413. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalos AC. Social indicators research and health-related quality of life. Soc Indicators Res. 2004;64:27–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soto M. Failde I. Marquez S, et al. Physical and mental component summaries score of the SF-36 in coronary patients. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:759–768. doi: 10.1007/pl00022069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brink E. Grankvist G. Karlson BW. Hallberg LR. Health-related quality of life in women and men one year after acute myocardial infarction. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:749–757. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0785-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norris CM. Hegadoren KM. Patterson L. Pilote L. Sex differences in prodromal symptoms of patients with acute coronary syndrome: A pilot study. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:27–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7117.2008.08010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford ES. Mokdad AH. Li C, et al. Gender differences in coronary heart disease and health-related quality of life: Findings from 10 states from the 2004 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. J Womens Health. 2008;17:757–768. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lloyd-Jones D. Adams RJ. Brown TM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update. A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121:e1–e170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suaya JA. Stason WB. Ades PA. Normand SL. Shepard DS. Cardiac rehabilitation and survival in older coronary patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SC., Jr Allen J. Blair SN, et al. AHA/ACC guidelines for secondary prevention for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2006 update. Endorsed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2006;113:2363–2372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavie CJ. Milani RV. Benefits of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training in elderly women. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:664–666. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wenger NK. Current status of cardiac rehabilitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1619–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balady GJ. Williams MA. Ades PA, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Epidemiology and Prevention, and Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2007;27:121–129. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000270696.01635.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavie CJ. Milani RV. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation programs on exercise capacity, coronary risk factors, behavioral characteristics, and quality of life in a large elderly cohort. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:177–179. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammill BG. Curtis LH. Schulman KA. Whellan DJ. Relationship between cardiac rehabilitation and long-term risks of death and myocardial infarction among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Circulation. 2010;121:63–70. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christian AH. Cheema AF. Smith SC. Mosca L. Predictors of quality of life among women with coronary heart disease. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mosca L. Banka CL. Benjamin EJ, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piepoli MF. Corra U. Benzer W, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:1–17. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283313592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glazer KM. Emery CF. Frid DJ. Banyasz RE. Psychological predictors of adherence and outcomes among patients in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2002;22:40–46. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200201000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allen JK. Scott LB. Stewart KJ. Young DR. Disparities in women's referral to and enrollment in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:747–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30300.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suaya JA. Shepard DS. Normand SL. Ades PA. Prottas J. Stason WB. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007;116:1653–1662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.701466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott LA. Ben-Or K. Allen JK. Why are women missing from outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs? A review of multilevel factors affecting referral, enrollment, and completion. J Womens Health. 2002;11:773–791. doi: 10.1089/15409990260430927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunlay SM. Witt BJ. Allison TG, et al. Barriers to participation in cardiac rehabilitation. Am Heart J. 2009;158:852–859. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanderson BK. Bittner V. Women in cardiac rehabilitation: Outcomes and identifying risk for dropout. Am Heart J. 2005;150:1052–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caulin-Glaser T. Maciejewski PK. Snow R. LaLonde M. Mazure C. Depressive symptoms and sex affect completion rates and clinical outcomes in cardiac rehabilitation. Prev Cardio. 2007;10:15–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1520-037.2007.05666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grace SL. Abbey SE. Shnek ZM. Irvine J. Franche RL. Stewart DE. Cardiac rehabilitation II: Referral and participation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(02)00179-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ades PA. Waldmann ML. Polk DM. Coflesky JT. Referral patterns and exercise response in the rehabilitation of female coronary patients aged greater than or equal to 62 years. Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:1422–1425. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)90894-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caulin-Glaser T. Blum M. Schmeizl R. Prigerson HG. Zaret B. Mazure CM. Gender differences in referral to cardiac rehabilitation programs after revascularization. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2001;21:24–30. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halm M. Penque S. Doll N. Beahrs M. Women and cardiac rehabilitation: Referral and compliance patterns. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1999;13:83–92. doi: 10.1097/00005082-199904000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Evenson KR. Rosamond WD. Luepker RV. Predictors of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation utilization: The Minnesota Heart Surgery Registry. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1998;18:192–198. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199805000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jackson L. Leclerc J. Erskine Y. Linden W. Getting the most out of cardiac rehabilitation: A review of referral and adherence predictors. Heart. 2005;91:10–14. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.045559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lieberman L. Meana M. Stewart D. Cardiac rehabilitation: Gender differences in factors influencing participation. J Womens Health. 1998;7:717–723. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott LB. Allen JK. Providers' perceptions of factors affecting women's referral to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs: An exploratory study. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:387–391. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cottin Y. Cambou JP. Casillas JM. Ferrieres J. Cantet C. Danchin N. Specific profile and referral bias of rehabilitated patients after an acute coronary syndrome. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:38–44. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200401000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cortes O. Arthur HM. Determinants of referral to cardiac rehabilitation programs in patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review. Am Heart J. 2006;151:249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grace SL. Gravely-Witte S. Kayaniyil S. Brual J. Suskin N. Stewart DE. A multisite examination of sex differences in cardiac rehabilitation barriers by participation status. J Womens Health. 2009;18:209–216. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Husak L. Krumholz HM. Lin ZQ, et al. Social support as a predictor of participation in cardiac rehabilitation after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2004;24:19–26. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore SM. Women's views of cardiac rehabilitation programs. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1996;16:123–129. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davidson PM. Daly J. Hancock K. Moser D. Chang E. Cockburn J. Perceptions and experiences of heart disease: A literature review and identification of a research agenda in older women. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:255–264. doi: 10.1016/S1474-5151(03)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benson G. Arthur H. Rideout E. Women and heart attack: A study of women's experiences. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs. 1997;8:16–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lloyd GW. Preventive cardiology and cardiac rehabilitation programmes in women. Maturitas. 2009;63:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Daly J. Sindone AP. Thompson DR. Hancock K. Chang E. Davidson P. Barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs: A critical literature review. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17:8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2002.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davidson P. Digiacomo M. Zecchin R, et al. A cardiac rehabilitation program to improve psychosocial outcomes of women with heart disease. J Womens Health. 2008;17:123–134. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2007.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Melloni C. Berger JS. Wang TY, et al. Representation of women in randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular disease prevention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:135–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.868307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaccarino V. Ischemic heart disease in women: Many questions, few facts. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:111–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.925313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beckie TM. Mendonca MA. Fletcher GF. Schocken DD. Evans ME. Banks SM. Examining the challenges of recruiting women into a cardiac rehabilitation clinical trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29:13–21. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31819276cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beckie TM. A behavior change intervention for women in cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;21:146–153. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200603000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beckie TM. Beckstead JW. Predicting cardiac rehabilitation attendance in a gender-tailored randomized clinical trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2010;30:147–156. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181d0c2ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Efron B. Forcing a sequential experiment to be balanced. Biometrika. 1971;58:403–417. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hofmeijer J. Anema PC. van der Tweel I. New algorithm for treatment allocation reduced selection bias and loss of power in small trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prochaska JO. Norcross JC. DiClemente CC. New York: HarperCollins; 1994. Changing for good. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rollnick S. Miller WR. Butler CC. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prochaska JO. Velicer WF. Redding C, et al. Stage-based expert systems to guide a population of primary care patients to quit smoking, eat healthier, prevent skin cancer, and receive regular mammograms. Prev Med. 2005;41:406–416. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller WR. Rollnick S. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller WR. Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64:527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller WR. Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2009;37:129–140. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Michalos A. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1991. Global report on student well-being: Volume 1: Life satisfaction and happiness. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mendes de Leon CF. Czajkowski SM. Freedland KE, et al. The effect of a psychosocial intervention and quality of life after acute myocardial infarction: The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease (ENRICHD) clinical trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2006;26:9–13. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tingstrom PR. Kamwendo K. Bergdahl B. Effects of a problem-based learning rehabilitation programme on quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pickering TG. Hall JE. Appel LJ, et al. Recommendations for blood pressure measurement in humans and experimental animals. Part 1: Blood pressure measurement in humans: A statement for professionals from the subcommittee of professional and public education of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2005;111:697–716. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000154900.76284.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jackson AS. Pollock ML. Ward A. Generalized equations for predicting body density of women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12:175–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gibbons RJ. Balady GJ. Bricker JT, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for exercise testing: Summary article: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1997 Exercise Testing Guidelines) Circulation. 2002;106:1883–1892. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034670.06526.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanderson BK. Phillips MM. Gerald L. DiLillo V. Bittner V. Factors associated with the failure of patients to complete cardiac rehabilitation for medical and nonmedical reasons. J Cardiopulm. Rehabil. 2003;23:281–289. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200307000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mosca L. Christian AH. Mochari-Greenberger H. Kligfield P. Smith SC. A randomized clinical trial of secondary prevention among women hospitalized with coronary heart disease. J Womens Health. 2010;19:195–202. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kaul S. Diamond GA. Trial and error. How to avoid commonly encountered limitations of published clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:415–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Froelicher ES. Miller NH. Buzaitis A, et al. The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Trial (ENRICHD): Strategies and techniques for enhancing retention of patients with acute myocardial infarction and depression or social isolation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:269–280. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gibbons RJ. Gardner TJ. Anderson JL, et al. The American Heart Association's principles for comparative effectiveness research: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;119:2955–2962. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]