Abstract

The serine proteinase urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) is widely recognized as a potential target for anticancer therapy. Its association with cell surfaces through the uPA receptor (uPAR) is central to its function and plays an important role in cancer invasion and metastasis. In the current study, we used systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) to select serum-stable 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine-modified RNA aptamers specifically targeting human uPA and blocking the interaction to its receptor at low nanomolar concentrations. In agreement with the inhibitory function of the aptamers, binding was found to be dependent on the presence of the growth factor domain of uPA, which mediates uPAR binding. One of the most potent uPA aptamers, upanap-12, was analyzed in more detail and could be reduced significantly in size without severe loss of its inhibitory activity. Finally, we show that the uPA-scavenging effect of the aptamers can reduce uPAR-dependent endocytosis of the uPA–PAI-1 complex and cell-surface associated plasminogen activation in cell culture experiments. uPA-scavenging 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine-modified RNA aptamers represent a novel promising principle for interfering with the pathological functions of the uPA system.

Keywords: uPA, uPAR, RNA aptamer, cancer metastasis, SELEX

INTRODUCTION

For cancer patients, metastases are the main cause of death. The invasion-metastasis cascade for cancer cells of epithelial origin consists of several steps, including detachment of tumor cells from the primary tumor, invasion and migration into the surrounding host tissue, entrance into circulatory systems, extravasation from the microvasculature of various tissues, and formation of micrometastases, which can eventually develop into macrometastases. In many of these steps, the serine protease urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) plays an important role (for review, see Andreasen et al. 1997; Ulisse et al. 2009).

uPA is the primary activator of plasminogen to plasmin on cell surfaces. Plasmin in turn is able, either directly or indirectly by activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), to degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) components and activate sequestered growth factors. These induced proteolytic processes are important for the breakdown of cell–cell and cell–matrix contacts during cell detachment from the primary tumor and for migration, but also enable the cell to traverse important barriers such as basement membranes during invasion. uPA is produced and secreted as an inactive soluble protease, pro-uPA, and consists of a C-terminal catalytic serine protease domain (SPD), a kringle domain, and an N-terminal growth factor domain (GFD). Activation occurs on the cell surface by proteolytic cleavage of the linker sequence between the SPD and the kringle domain; however, the two chains remain linked by a disulphide bridge. Cell surface association is mediated by the GFD, which binds to the glycolipid-anchored uPA receptor (uPAR). The catalytic activity of uPA is mainly inhibited by the serpin plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), thus making plasminogen activation a highly controlled temporary and localized event. Inhibition of uPA by PAI-1 results in the formation of an inactive covalently linked uPA–PAI-1 complex, which is internalized together with uPAR by endocytosis receptors of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family, leading to lysosomal degradation of uPA–PAI-1 and recycling of free uPAR to the cell surface (for review, see Dupont et al. 2009). Beside being a protease, uPA is involved in molecular interactions independent of its proteolytic activity. Binding of uPA to uPAR stimulates uPAR binding to the ECM protein vitronectin, regulates uPAR–integrin interaction, and plays a role in cell signaling (Ulisse et al. 2009).

Numerous independent studies have demonstrated that cancer patients with low levels of uPA, uPAR, or PAI-1 in their primary tumor have a significantly better prognosis than patients with high levels (for review, see Duffy and Duggan 2004). Recently, uPA and PAI-1 levels were recommended by American Society for Clinical Oncology (ASCO) in the clinical management of breast cancer (Harris et al. 2007). Consistently, more than two decades of research support a tumor biological role of uPA-mediated plasminogen activation (Andreasen et al. 1997; Ulisse et al. 2009). Interfering with either the uPA–uPAR interaction or directly with the catalytic activity of uPA has been found to inhibit tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis in animal models of cancer. However, uPAR not only localizes proteolysis at the cell surface, the mere binding of uPA affects chemotaxis, cell migration and invasion, adhesion, proliferation, and angiogenesis by modulating the interactions with cellular receptors, adhesion molecules, and ECM proteins. This implies that the many generated inhibitors targeting the catalytic SPD of uPA will not block all functions of the uPA–uPAR complex. Furthermore, most uPA–uPAR blocking agents bind to uPAR and can still induce uPA–uPAR-like downstream interactions. This suggests that a better strategy for complete inhibition of uPA–uPAR complex-dependent functions is to develop uPA-directed inhibitors that block formation of the uPA–uPAR complex.

Here, we present for the first time a nuclease-resistant 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine-modified (2′-F-Y) RNA aptamer targeting uPA and blocking the interaction of uPA with its receptor uPAR. The in vivo therapeutic potential of aptamers has been illustrated by the FDA approval of an aptamer to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for the treatment of the wet form of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Ruckman et al. 1998; Pestourie et al. 2005). Nucleic acid aptamers are generated by systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX), which combines the ability of oligonucleotides to fold into a variety of three-dimensional structures with the possibility of selecting, from very large pools of random sequences (∼1015), those variants that bind to a target of interest. Aptamers typically bind their targets with low nanomolar to picomolar affinity and high specificity. Based on their low immunogenicity and ease of synthesis and modification, they represent an interesting supplement to small molecules, peptides, and antibodies in the development of protein-targeting agents for use in basic research, therapy, and diagnostics.

RESULTS

Selecting 2′-F-Y RNA aptamers to human uPA

To identify nucleic acid aptamers binding to human uPA, we produced a library of ∼1015 different 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine-modified (2′-F-Y) RNA sequences and screened it by affinity chromatography for variants capable of binding to uPA. uPA was captured on Protein A Sepharose using anti-uPA antibodies. From round 6 to round 8 in the selection, we observed a significant increase in the fraction of 32P-labeled pool variants that was retained on the uPA-Sepharose (sixth: ∼6%; seventh: ∼11%; eighth: ∼15%). Among 40 individual clones sequenced after selection round 8, several were sequence-identical and some showed significant sequence similarity in the degenerate region. The 29 different sequence variants were subjected to further analysis.

Screening 2′-F-Y RNA aptamer candidates for functional effects

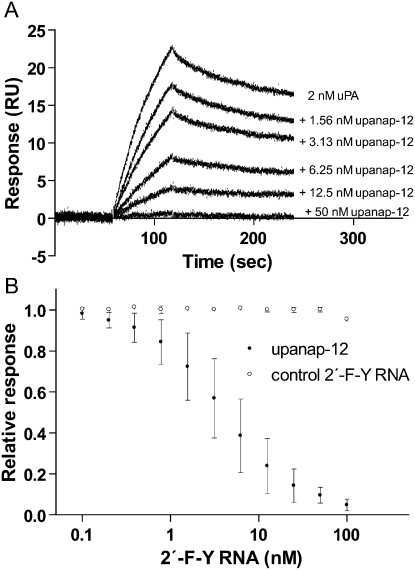

The identified candidates were screened for their ability to inhibit the proteolytic activity of uPA as well as uPA–uPAR binding. In an SPR experiment, in which we immobilized uPAR on the sensor surface and measured the binding of uPA in the presence of increasing concentrations of the different aptamer candidates, we found that several were able to inhibit binding of uPA to uPAR, as exemplified by upanap-12 (uPA nucleic acid aptamer number 12) in Figure 1A. From plots of the amount of uPA captured as a function of aptamer concentration (as shown for upanap-12 in Fig. 1B), the IC50-values for inhibition of uPA–uPAR binding were found to be below 100 nM for 13 candidates (see Table 1). In an identical setup with mouse uPA and mouse uPAR immobilized on the sensor chip, no detectable inhibition was found for any of the aptamers in concentrations up to 250 nM (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Upanap-12 inhibits binding of uPA to uPAR. (A) SPR sensorgram showing the capture of 2 nM human uPA (injected from seconds 60 to 120) on a sensor surface with immobilized human uPAR in the presence of increasing concentrations of upanap-12. (B) The reported uPA capture level after injection in each case was plotted as a function of the upanap-12 concentration relative to the response of 2 nM uPA alone. A sequence-unrelated 2′-F-Y control RNA was analyzed for comparison. For IC50-value, standard deviations, and number of independent experiments, see Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Selected 2′-F-Y RNA aptamers binding to human uPA and inhibiting its interaction with uPAR

None of the isolated aptamers were found to inhibit the proteolytic activity of uPA detectably, neither in an assay measuring the hydrolysis of an artificial chromogenic peptide substrate, nor based on activation of plasminogen to plasmin in solution (data not shown).

uPA aptamer upanap-12 binds to the growth factor domain of uPA

As a representative of aptamers inhibiting the uPA–uPAR interaction (see above), upanap-12 was further analyzed. Considering the functional effect, the aptamer binding site was assumed to be near the GFD of uPA, which is responsible for uPA binding to uPAR. We therefore investigated the binding of upanap-12 to different forms and deletion variants of uPA captured on SPR sensor surfaces with immobilized polyclonal anti-uPA antibodies (Fig. 2). Upanap-12 bound with similar affinity to active uPA and to the catalytically inactive proform of uPA (pro-uPA), while there was no measurable binding to uPA variants lacking the GFD (ΔGFD-uPA) or both the GFD and the kringle domain (LMW-uPA). Additionally, we found no detectable binding of upanap-12 to uPA captured on SPR sensor surfaces using immobilized uPAR (data not shown). Identical results were obtained for upanap-21, upanap-26, upanap-71, and upanap-79 (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

The binding of upanap-12 to uPA requires the GFD. The relative association of upanap-12 to different variants of uPA is indicated: The inactive zymogen form of uPA (pro-uPA) active uPA (uPA), uPA without the growth factor domain (ΔGFD), and uPA without the entire ATF (also called low molecular weight uPA; LMW-uPA). The domain structure of the different variants is shown at each bar, while the inset illustrates pro-uPA with domain designations: (GFD) growth factor domain, (KD) kringle domain, and (SPD) serine protease domain. uPA variants were captured on an SPR sensor surface containing immobilized polyclonal anti-uPA antibody to the following levels: pro-uPA (215–280 RU), uPA (210–260 RU), ΔGFD-uPA (210–230 RU), and LMW-uPA (140–160 RU). The binding level of 50 nM upanap-12 to each captured variant was subsequently recorded. Using the molecular weight of the different variants, the binding level of aptamers per mole of captured variant was calculated and presented relative to the pro-uPA result. Open bars represent mean values and standard deviations derived from three independent experiments.

uPA aptamer upanap-12 can inhibit the binding of uPA to uPAR on the cell surface

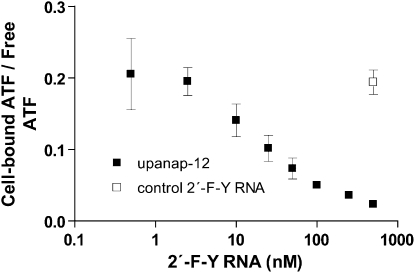

To verify that uPA aptamer upanap-12 can inhibit the binding of uPA to not only purified soluble uPAR but also to uPAR in its natural environment on the cell surface, we investigated the binding of 125I-labeled human ATF (uPA without the SPD) to the uPAR-expressing monocytic cell line U937 in the presence of varying concentrations of upanap-12 (Fig. 3). Upanap-12 was found to inhibit ATF binding with an IC50 of 17.0 ± 1.6 nM, while the control 2′-F-Y RNA oligonucleotide did not have any effect.

FIGURE 3.

Upanap-12 can inhibit cell binding of uPA. A total of 3 pM of 125I-ATF (the GFD and KD of uPA) and different concentrations of upanap-12 were incubated with U937 cells overnight at 4°C, followed by γ-counting of cell pellets and supernatants. The ratio of cell-bound 125I-ATF to free 125I-ATF was plotted as a function of the concentration (in log scale) of upanap-12 (▪) or a sequence-unrelated 2′-F-Y RNA control (□) only analyzed at the highest concentration. Shown are mean result and standard deviations derived from three independent experiments.

As the experiment was an equilibrium-binding cell culture experiment with an overnight incubation at 4°C, we investigated in parallel the stability of the upanap-12 uPA aptamer in cell culture medium containing 10% FCS (data not shown). After overnight incubations at 4°C, 25°C, or even 37°C, we did not observe any significant degradation of our 2′-F-Y RNA oligonucleotide, whereas an all-RNA version of the aptamer was undetectable in such assays, indicating complete degradation.

uPA aptamer upanap-12 truncation variants

On the basis of sequence alignment and secondary structure predictions, the isolated sequences displayed a high degree of similarity. Five of the six sequences with the most potent inhibitory activity toward the uPA–uPAR interaction (upanap-12, upanap-21, upanap-25, upanap-71, and upanap-79; Table 1) feature a conserved asymmetrical internal loop sequence, CGA, and a conserved hairpin loop, (U/C)AACC (Fig. 4A). The similar arrangement of these sequence elements in the different aptamers suggested that the binding and inhibitory activity could be retained in smaller truncated versions. Two truncation variants of full-length upanap-12 (Fig. 4B) were synthesized (upanap-12.49 and upanap-12.33) (see Fig. 4C,D). To facilitate synthesis by T7 RNA polymerase, the two 5′-terminal nucleotides were changed into guanosines and the base-pairing partners at the 3′-end into 2′-fluoro-cytidines in both truncation variants. The uPA–uPAR inhibitory activities of the two variants were compared with the full-length version by SPR analysis, where uPAR was immobilized on the sensor surface and uPA passed over in the presence of increasing concentrations of aptamer (as demonstrated with upanap-12 in Fig. 1). As found for upanap-12, the two truncation variants were able to completely block uPA binding to uPAR. While upanap-12.49 was found to be similarly effective as full-length upanap-12 in this assay (IC50 = 5.1 nM ± 1.1, n = 5), upanap-12.33 had an approximately twofold reduced activity (IC50 = 11.6 nM ± 4.5, n = 3). The latter result was unexpected since the region excluded from upanap-12.33 compared with upanap-12.49 is rather different for upanap-12, upanap-21, upanap-25, upanap-71, and upanap-79 as deduced from secondary structure prediction (data not shown). Since the upanap-12.49 variant had the same inhibitory potential as the full-length version in our SPR uPA–uPAR competition experiment, we chose to do cell culture experiments with this truncated variant.

FIGURE 4.

Full-length upanap-12 and truncation variants. (A) Conserved elements of the secondary structures predicted for upanap-12, upanap-21, upanap-25, upanap-71, and upanap-79, featuring the two stems, the asymmetrical loop, and the hairpin loop. Duplex regions are highlighted in gray, X indicates any base (A, G, C, or U), Py indicates a pyrimidine (C or U), and Pu indicates a purine (G or A). (B–D) The predicted secondary structures of (B) full-length upanap-12, (C) upanap-12.49, and (D) upanap-12.33. Note that the 5′- and 3′-ends for upanap-12.49 and upanap-12.33 have been mutated compared with the full-length sequence to allow efficient production of transcripts by T7 RNA polymerase.

uPA aptamer upanap-12.49 blocks receptor-mediated endocytosis of the uPA–PAI-1 complex

The reaction between uPA and its primary physiological inhibitor PAI-1 results in the formation of a covalently linked uPA–PAI-1 complex with an inactivated SPD. When bound to uPAR on the cell surface, the uPA–PAI-1 complex will be endocytosed and degraded by binding to clathrin-coated pit-localized receptors of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family (for review, see Dupont et al. 2009). In the SPR uPA–uPAR competition experiment, reaction of PAI-1 with uPA was found not to reduce the uPAR blocking function of aptamers (data not shown). We therefore tested whether the receptor-mediated endocytosis of uPA–PAI-1 could be inhibited by the isolated upanap aptamers. As shown in Figure 5, degradation of the 125I-labeled uPA–PAI-1 complex by U937 cells, which express both VLDLR and uPAR, was inhibited by upanap-12.49, whereas an unrelated 2′-F-Y RNA had no effect.

FIGURE 5.

uPA binding aptamers can inhibit uPAR- and VLDLR-dependent endocytosis of uPA–PAI-1 complex in U937 cells. 125I-labeled uPA–PAI-1 complexes were incubated with U937 cells for 3 h at 37°C in the presence of the indicated concentrations of upanap-12.49, a sequence-unrelated control 2′-F-Y RNA, or uPA. After incubation, the uPAR- and VLDLR-mediated degradation of the uPA–PAI-1 complex was determined by trichloroacetic acid precipitation and γ-counting. Only intact 125I-uPA–PAI-1 protein can be precipitated by trichloroacetic acid, while smaller peptide fragments or amino acids will stay in solution. Shown are mean values and standard deviations derived from three independent experiments.

uPA aptamer upanap-12.49 inhibits cell surface-associated plasminogen activation

As uPA-mediated plasminogen activation plays an important role in tumor biology, we investigated whether the inhibitory function of the aptamers on the uPA–uPAR interaction on cell surfaces could interfere with cell surface-associated plasminogen activation. Free active plasmin has only a short half-life in blood plasma, owing to rapid reaction with proteinase inhibitors, primarily α2-antiplasmin, whereas cell surface-associated plasmin is protected from α2-antiplasmin. We therefore followed plasmin generation in a cell culture assay in the presence of α2-antiplasmin, starting plasminogen activation by the addition of pro-uPA (Fig. 6A,B). Plasmin generation was significantly inhibited by upanap-12.49. It was also inhibited by a soluble version of uPAR without the glycolipid anchor, which sequesters pro-uPA, and thus prevents it from binding to uPAR at the cell surface.

FIGURE 6.

The effect of upanap-12.49 on cell surface-asociated plasminogen activation. (A) Illustration of the experimental setup. Upon binding of pro-uPA to uPAR-expressing U937 cells, pro-uPA is activated and converts cell surface-associated plasminogen to plasmin, providing the cell surface with locally confined proteolytic activity. The presence of α2-antiplasmin, a fast inhibitor of plasmin activity in solution, but not on the cell surface, ensures that the observed cleavage of a fluorogenic plasmin substrate is a result of cell surface-associated plasmin activity only. (B) Cells, plasminogen and α2-antiplasmin were mixed and preincubated for 15 min at 37°C before the addition of pro-uPA and the plasmin fluorogenic substrate, either in the presence or absence of upanap-12.49, a sequence-unrelated control 2′-F-Y RNA, or suPAR. Cell surface-associated plasmin activity was measured by fluorescence emission at 480 nm, resulting from the cleaved fluorogenic substrate after subtraction of uPA-independent background cleavage (given as arbitrary units). Data points are mean values and standard deviations derived from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we generated a new type of uPA-binding agent, so-called 2′-fluoro-pyrimidine-modified (2′-F-Y) RNA aptamers, which were found to block the binding of uPA to uPAR. Previously, Skrypina et al. (2004) reported the selection of a pool of single-stranded DNA sequences with increased affinity to pro-uPA after 12 rounds of selection compared with the initial library pool. However, no further characterization was undertaken in this study. Recently, 2′-F-Y RNA aptamers have also been selected toward the inhibitor of uPA, PAI-1 (Blake et al. 2009; Madsen et al. 2010).

Our selection identified 29 aptamer candidates of different sequence after eight rounds of selection. As we were interested in aptamers with functional effects, we screened the 29 aptamer candidates for inhibitory effects toward the catalytic activity of uPA and uPA–uPAR binding. The results revealed 13 uPA aptamers with the ability to inhibit uPA–uPAR binding at low nanomolar concentrations (Table 1), but none inhibiting the catalytic activity of uPA. The specificity of the aptamers was illustrated by the inability to interfere with mouse uPA binding to mouse uPAR.

Detailed studies on the uPA–uPAR interaction have shown that the GFD of uPA (residues 1–48) is responsible for uPAR binding primarily as a result of extensive burial of the β-hairpin loop of GFD into the central cavity of the uPAR structure (Ploug 2003; Barinka et al. 2006; Huai et al. 2006). SPR analysis of aptamer binding to uPA variants and domain deletion constructs revealed that aptamer binding was dependent on the presence of the GFD in uPA (Fig. 2). This was in good agreement with the inhibitory activity of the aptamers and the inability to bind uPA when already associated with uPAR. In addition, aptamer binding was not affected by the structural differences of the serine protease domain (SPD) in pro-uPA and uPA arising from pro-enzyme activation.

As we were unable to find any obvious differences in the characteristics of the six most potent uPA–uPAR inhibitory aptamers, we focused our attention on one aptamer, upanap-12 (Fig. 4B). We attempted to perform a detailed kinetic analysis on the binding of upanap-12 to uPA by SPR, but our binding curves could not be fitted to a simple 1:1 binding algorithm (data not shown). However, upanap-12 was shown to inhibit the binding of 125I-labeled ATF (amino-terminal fragment; uPA without the SPD) to U937 cells at low nanomolar concentrations (Fig. 3), thus confirming its inhibitory effect on the uPA–uPAR interaction in a more native environment for uPAR than in the initial SPR experiments.

Comparative secondary structure predictions for the selected uPA aptamers revealed pronounced similarities among five of the six most potent inhibitory aptamers and suggested that the characteristics of upanap-12 could be retained in smaller truncated variants of this aptamer (Fig. 4A). A 33-nt-long variant, upanap-12.33 (∼11 kDa) (Fig. 4D) was found to inhibit the uPA–uPAR interaction with only a minor effect on the IC50 in the SPR assay relative to full-length upanap-12 (∼26 kDa) (Fig. 4B). In addition, we also constructed a 49-nt-long variant of upanap-12, upanap-12.49 (∼16 kDa) (Fig. 4C), which was indistinguishable from the full-length version in terms of its uPA–uPAR inhibitory activity in the SPR assay.

We subsequently used upanap-12.49 to study processes known to depend on uPA–uPAR interaction at the cell surface. First, we demonstrated that the aptamer could inhibit endocytosis of the uPA–PAI-1 complex (Fig. 5), in agreement with previous findings that fast endocytosis depends on uPAR binding before endocytosis receptor binding (for review, see Dupont et al. 2009). Secondly, we showed the effect of the aptamer on uPA-mediated plasminogen activation on cell surfaces, which has been shown by both in vitro and in vivo studies to play an important causal role in cancer (for review, see Andreasen et al. 1997; Ulisse et al. 2009). The concomitant assembly of plasminogen and uPA on the cell surfaces of U937 cells greatly increases the rate of cell surface-associated plasminogen activation (Ellis et al. 1989), but could be inhibited by the upanap-12.49 aptamer (Fig. 6A,B) with comparable efficiency to soluble uPAR, which has a KD for uPA in the picomolar range.

In many cases, tumor growth and/or metastasis have been inhibited in rat or mouse models of cancer by using uPA–uPAR blocking agents such as the ATF, the GFD, soluble uPAR, peptides targeting the central cavity of uPAR, as well as polyclonal anti-uPAR antibody preparations, validating this interaction as an attractive potential target for anticancer therapy (Ulisse et al. 2009). However, most agents are directed toward the receptor, and are often still able to mediate some downstream nonproteolytic events involving uPAR. For example, ATF or a peptide corresponding to the sequence of uPA mediating uPAR binding (residues 12–32 of the human sequence) still induce cytoskeletal rearrangements and extension of protrusions (Carriero et al. 1999). The same was observed when using a synthetic peptide antagonist binding to uPAR, developed by phage display technology and combinatorial chemistry (Hillig et al. 2008). Other experiments have shown that the same and/or similar agents targeting the uPA-binding pocket were also still able to stimulate vitronectin–uPAR binding (Tressler et al. 1999), uPAR-mediated cell adhesion to vitronectin (Hillig et al. 2008), chemotaxis (Resnati et al. 1996), and to rescue cells from apoptosis (Alfano et al. 2006). Structure analyses imply that agents targeting the uPA binding region of uPAR stabilize the receptor in an active conformation, which can engage in interactions with other uPAR ligands like vitronectin and perhaps integrins (Yuan and Huang 2007). Targeting uPA directly to prevent its binding to uPAR therefore appears as a more specific way of inhibiting cell surface-associated plasminogen activation, because it avoids the activation of adhesive and signaling functions of uPAR.

Soluble variants of the uPA receptor are efficient scavengers of uPA (Fig. 6) and have been shown to reduce tumor growth and spread in mice (Lutz et al. 2001), but whether the anticancer activity of suPAR is due to uPA scavenging or results from competitive inhibition of cell surface uPA–uPAR interaction with other molecules is a matter of debate (Jo et al. 2003). At least for some cell types, it has been reported that suPAR can also activate integrins to induce cell adhesion and cell signaling (May et al. 1998; Jo et al. 2003). In addition, the use and understanding of suPAR as a uPA–uPAR-inhibiting anticancer compound is complicated by the fact that a high level of suPAR is correlated with a poor prognosis for cancer patients (Duffy and Duggan 2004).

Blocking the uPA–uPAR interaction by targeting uPA has been studied using monoclonal antibodies in vitro, but to our knowledge, not in vivo. In cell culture experiments such antibodies inhibit (1) uPA-induced migration of MCF-7 cells (Nguyen et al. 1999), (2) the mitogenic effect caused by adding exogenous uPA or ATF to ovarian carcinoma cells (Fishman et al. 1999) or exogenous epidermal growth factor (EGF) to MDA-MB-231 cells (Jo et al. 2007), (3) as well as the effects of endogenously produced uPA on cell growth and rescue of MDA-MB-231 cells from apoptosis (Ma et al. 2001). The role of the uPA–uPAR interaction in prevention of apoptosis for some cancer cells suggests that uPA-directed uPA–uPAR inhibitors may in some cases lead to tumor regression, an important property of a potential anticancer compound.

In light of the currently available ensemble of uPA–uPAR inhibitory agents, the uPA aptamers described here represent an interesting novel tool for studying the pathophysiological role of the uPA–uPAR interaction in vitro. Also, inhibiting uPA's binding to its receptor by targeting the ligand rather than the receptor is an unusual approach in the field. Upon grafting the aptamers with polyethylene glycol moieties to avoid rapid kidney clearance, the aptamers will also be obvious in vivo applicable agents for use with xenograft mouse models, and therefore, potential candidates toward developing anticancer therapies targeting uPA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins and antibodies

Human two-chain uPA was from Wakamoto Pharmaceutical Company, while human pro-uPA and mouse uPA were from Molecular Innovations. Low molecular weight human uPA (LMW-uPA), i.e., uPA N-terminally truncated at Lys136, and the amino-terminal fragment (ATF; Ser1–Lys135) was prepared by proteolytic cleavage of full-length two-chain uPA (Egelund et al. 2001). The uPA variant lacking the growth factor domain (ΔGFD-uPA) was produced recombinantly (Skeldal et al. 2006). Human and mouse soluble uPAR, lacking the glycolipid anchor, were kindly provided by Michael Ploug, Finsen Laboratory, Copenhagen, Denmark. Active natural glycosylated PAI-1 as well as recombinant PAI-1 was prepared as described previously (Dupont et al. 2006). The mutant T7 RNA polymerase Y639F was expressed and prepared essentially as described previously (Grügelsiepe et al. 2005). The monoclonal antibody to uPA (anti-uPA clone 6) was described previously (Petersen et al. 2001), as was the rabbit polyclonal anti-uPA antibody (Knoop et al. 1998).

Cells

U937 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing L-glutamine supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Cambrex). MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in DMEM medium with 4.5 g/L glucose and with L-Glutamin, 10% FCS, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Cambrex) and passaged using Trypsin-EDTA solution (Cambrex).

RNA library construction and aptamer selection

Selection of aptamers to uPA basically followed the guidelines described, with minor modifications (Kenan and Keene 1999). Oligonucleotides were obtained from DNA Technology A/S: The “Forward N35” library primer (5′-CGCGGATCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCCACCAACGACATT-3′) contained the T7 promoter sequence and the “N35 library” primer (5′-GATCCATGGGCACTATTTATATCAAC(N35)AATGTCGTTGGTGGCCC-3′) included the degenerate sequence. To generate a library of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) transcription templates, the “Forward N35” and “N35 library” primers were annealed by heating to 75°C for 15 min and slowly cooling to room temperature. Annealed primers were extended by Klenow polymerase (3′ = >5′ exo; New England Biolabs), dsDNA products purified on a 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel (National Diagnostics), and retrieved by passive elution. The concentration of dsDNA was determined by UV spectroscopy at 260 nm (1 A260 unit = 50 μg/mL). The RNA library was transcribed in a reaction containing 80 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 30 mM DTT, 25 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine-HCl, 2.5 mM each ATP and GTP (GE/Healthcare/Amersham Bioscences), and 2.5 mM each 2′-F-dCTP and 2′-F-dUTP (TriLink Biotechnologies), 100 μg/mL acetylated BSA (Ambion/Applied Biosystems), 45 μg/mL dsDNA template (corresponding to 1015 template molecules), and 150 μg/mL mutant T7 RNA polymerase Y639F. Reactions were extracted using phenol/chloroform (pH 6.6) and purified on Nap-5 columns (GE Healthcare/Amersham Biosciences). 2′-F-Y RNA concentrations were determined by UV spectroscopy at 260 nm (1 A260 unit = 40 μg/mL).

2′-F-Y RNA sequences with affinity to uPA were selected using uPA-conjugated Sepharose. A total of 10 mg of Protein A Sepharose (GE Healthcare/Amersham Biosciences) was incubated with a mixture of 5 μg of monoclonal anti-uPA antibody Mab-6 and 5 μg of a rabbit polyclonal anti-uPA antibody in HEPES-buffered saline (pH 7.2; HBS) with 0.01% Tween20 (HBSTW) overnight at 4°C, followed by washing. One-half of the antibody-conjugated beads were used for counter selection to remove RNA sequences binding to the Protein A Sepharose or the antibodies. The other half was incubated with 5 μg of uPA for 30 min at room temperature, followed by washing. In the first selection round, counter-selection beads were incubated with 50 μM RNA library in HBSTW containing 2 mM MgCl2, 25 μg/mL tRNA (Sigma-Aldrich), 25 μg/mL poly AGC (Sigma-Aldrich), and 100 μg/mL BSA (New England Biolabs) for 30 min at room temperature. Unbound material was then incubated with uPA-conjugated beads for 30 min at room temperature. After extensive washing, bound 2′-F-Y RNA sequences were eluted by Proteinase K digestion (New England Biolabs) and harvested by phenol/chloroform extraction (pH 6.6) and ethanol coprecipitation with tRNA. 2′-F-Y RNAs were reverse transcribed using the primer “Reverse N35” (5′-CCCGACACCCGCGGATCCATGGGCACTATTTATATCAA-3′) and AMV RT (Promega). dsDNA transcription templates for the next round of selection were then generated by PCR using “Forward N35” and “Reverse N35” primers and Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), followed by BamHI digestion (New England Biolabs), phenol/chloroform extraction (pH 7.9), and ethanol precipitation. 2′-F-Y RNA for subsequent rounds of selection were produced in the presence of trace amounts of [α-32P]ATP and purified by Nap-5 columns (rounds 2–5) or on a 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gel (rounds 6–8). The 2′-F-Y RNA concentration during selection was 500 nM in rounds 2–5, and 100 nM in rounds 6–8. The amount of 2′-F-Y RNA bound to uPA-conjugated Sepharose beads was determined by scintillation counting in every round. After round 8, the pool of dsDNA transcription templates was ligated into a plasmid vector for sequencing (TOPO TA Cloning Kit; Invitrogen). The variable part of the sequences was aligned using the multiple sequence alignment program ClustalW found at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw (Chenna et al. 2003). The shown secondary structures in Figure 4 and the marked duplex regions in Table 1 are based on the lowest energy solutions predicted using the MFOLD program at http://www.frontend.bioinfo.rpi.edu/applications/mfold/cgi-bin/rna-form1-2.3.cgi (Mathews et al. 1999; Zuker 2003).

Peptidolytic inhibition assay

A total of 2 nM uPA was preincubated alone or in the presence of 40 nM PAI-1 or 100 nM for individual 2′-F-Y RNA oligonucleotides for 10 min at 37°C in HBSTW containing 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% BSA, followed by addition of one volume of 1 mM or 50 μM chromogenic substrate, S-2444 (pyro-Glu-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide; Chromogenix). S-2444 hydrolysis was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm over a time period of 50 min at 37°C. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Plasminogen activation assay in solution

A total of 0.5 nM uPA was preincubated for 10 min at 37°C in HBSTW containing 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% BSA, and 1 mM plasmin-sensitive fluorogenic substrate (I-1390, H-D-Val-Leu-Lys-AMC; Bachem Bioscience) either in the absence or presence of 40 nM PAI-1 or 250 nM 2′-F-Y RNA. The reaction was started by adding 1 vol prewarmed 200 nM Glu-Plasminogen (Molecular Innovations), and fluorescence emission at 480 nm was monitored at 37°C in a Spectramax Gemini fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices) using an excitation wavelength of 390 nm. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments

Experiments were carried out using a Biacore T100 (GE Healthcare/Biacore). To investigate the uPA–uPAR inhibitory activity of the aptamers, 5 μg/mL human or mouse soluble uPAR were prepared in 10 mM NaOAc (pH 5.0) and immobilized on an EDC/NHS-activated CM5 sensor surface to a level of 1000 and 500 RU, respectively, using the Biacore immobilization wizard. Reference surfaces were blocked with ethanolamine. Human uPA (2 nM), mouse uPA (3 nM), or human uPA–PAI-1 complex (2 nM), either with or without aptamer, was prepared in running buffer (HBS, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% BSA and 0.025% Tween20), and passed over the sensor surfaces at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. uPA–PAI-1 samples were prepared from a reaction between 30 nM uPA and excess recombinant PAI-1 (300 nM) in HBS for 15 min at 37°C. Sensor surfaces were regenerated with 100 mM acetic acid (pH 2.8) containing 0.5 M NaCl. IC50-values were estimated by nonlinear regression analysis, fitting the data to a standard one-site competition model using Graph Pad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software). The 2′-F-Y control RNA oligonucleotide had the sequence 5′-GGGGCCACCAACGACAUUAACUCACGUUGCAACUAAUACGCUGAGUGGAAACCGUUGAUAUAAAUAGUGCCCATGGAUC-3′.

For studying binding of aptamers to different forms of uPA, 30 μg/mL rabbit polyclonal anti-uPA antibody (F1609) in NaOAc (pH 5.0) was immobilized on CM5 sensor surfaces to a level of 5000 RU. uPA variants were captured on the sensor surface as indicated in the Figure 2 legend, and the binding level of 50 nM upanap-12 subsequently recorded. Based on the molecular weight of each variant, the amount of aptamer bound per mole captured uPA variant was calculated. The molecular weight of uPA variants used for calculations were: 51,000 for pro-uPA and uPA, 46,000 for ΔGFD-uPA, and 35,000 for LMW-uPA.

Association of 125I-ATF with U937 cells

Human ATF was labeled with 125I using chloramin T as the oxidizing agent essentially as described previously (Jensen et al. 1990). Samples containing 106 U937 cells, 3 pM 125I-ATF and 0–500 nM upanap-12 or 500 nM of the control oligonucleotide were prepared in 1 mL of culture medium and incubated overnight at 4°C on a carrousel. Cells were then pelleted and half of the supernatant collected for γ-counting. The pellet was washed with serum-free culture medium and also subjected to γ-counting. The bound 125I-ATF divided by free 125I-ATF was plotted as a function of the upanap-12 concentration (in logarithmic scale).

RNase stability assay for upanap-12

A total of 400 ng of unmodified or 2′-F-pyrimidine-modified upanap-12 was incubated for 14 h at 4°C, 25°C, or 37°C in RPMI media containing 10% FCS, and analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels containing ethidium bromide.

Effect of human uPA-aptamers on receptor-mediated endocytosis and degradation of 125I-uPA–PAI-1 complexes

125I-labeling of uPA was performed as described previously (Nykjaer et al. 1994). Complexes between 125I-uPA and purified PAI-1 were prepared as described (Kasza et al. 1997). Next, 4 × 106 U937 cells in 400 μL RPMI 1640 cell medium containing 0.5% BSA were mixed with 50 μL 100 pM 125I-uPA–PAI-1 and either 50 μL of medium, uPA, upanap-12.49 or 200 nM of a truncated control 2′-F-Y RNA (5′-GGACGACAUUAACUCACGUUGCAACUAAUACGCUGAGUGGAAACCGUCC-3′), followed by incubation for 3 h at 37°C with occasional resuspension of the cells. A mixture of 450 μL RPMI containing 0.5% BSA with 50 μL 125I-uPA–PAI-1 was included to determine spontaneous degradation of the complex (cell-free sample). After 3 h, the samples were cooled on ice and intact protein was precipitated using 120 μL of 72% TCA. The samples were then centrifuged, and half of the supernatant collected for γ-counting. Pellets were washed once with 1 mL of 7% TCA and subjected to γ-counting as well. Based on the radioactivity measurements, the fractional cell-mediated degradation of 125I-uPA–PAI-1 was calculated after subtracting the degradation that occurred in samples without cells.

uPA-mediated plasminogen activation on the cell surface

Before use, U937 cells were treated with Aprotinin, low pH buffer, and finally washed with HBS containing 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.1% BSA. Then 3 × 106 cells/mL were preincubated for 15 min at 37°C with 400 nM α2-antiplasmin (Molecular Innovations) and 200 nM Glu-Plasminogen, and at time zero mixed with 1 vol containing 2 nM pro-uPA and 1 mM of the plasmin-sensitive fluorogenic substrate I-1390, either in the presence or absence of upanap-12.49, the truncated 2′-F-Y RNA oligonucleotide, or soluble uPAR. The fluorescence of the wells was monitored at 37°C in the Spectromax Gemini fluorescence plate reader.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Ploug from the Finsen Laboratory in Copenhagen, Denmark for his generous donation of uPAR. This work was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (26-331-6), the Danish Cancer Society (DP 07043, DP 08001), the Danish Research Agency (272-06-0518), the Novo-Nordisk Foundation (R114-A11382), and the Danish Cancer Research Foundation (72-07).

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2338210.

REFERENCES

- Alfano D, Iaccarino I, Stoppelli MP 2006. Urokinase signaling through its receptor protects against anoikis by increasing BCL-xL expression levels. J Biol Chem 281: 17758–17767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen PA, Kjoller L, Christensen L, Duffy MJ 1997. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator system in cancer metastasis: A review. Int J Cancer 72: 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barinka C, Parry G, Callahan J, Shaw DE, Kuo A, Bdeir K, Cines DB, Mazar A, Lubkowski J 2006. Structural basis of interaction between urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor. J Mol Biol 363: 482–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake CM, Sullenger BA, Lawrence DA, Fortenberry YM 2009. Antimetastatic potential of PAI-1-specific RNA aptamers. Oligonucleotides 19: 117–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriero MV, Del Vecchio S, Capozzoli M, Franco P, Fontana L, Zannetti A, Botti G, D'Aiuto G, Salvatore M, Stoppelli MP 1999. Urokinase receptor interacts with αvβ5 vitronectin receptor, promoting urokinase-dependent cell migration in breast cancer. Cancer Res 59: 5307–5314 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3497–3500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy MJ, Duggan C 2004. The urokinase plasminogen activator system: A rich source of tumour markers for the individualised management of patients with cancer. Clin Biochem 37: 541–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont DM, Blouse GE, Hansen M, Mathiasen L, Kjelgaard S, Jensen JK, Christensen A, Gils A, Declerck PJ, Andreasen PA, et al. 2006. Evidence for a pre-latent form of the serpin plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 with a detached β-strand 1C. J Biol Chem 281: 36071–36081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupont DM, Madsen JB, Kristensen T, Bodker JS, Blouse GE, Wind T, Andreasen PA 2009. Biochemical properties of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Front Biosci 14: 1337–1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelund R, Petersen TE, Andreasen PA 2001. A serpin-induced extensive proteolytic susceptibility of urokinase-type plasminogen activator implicates distortion of the proteinase substrate-binding pocket and oxyanion hole in the serpin inhibitory mechanism. Eur J Biochem 268: 673–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis V, Scully MF, Kakkar VV 1989. Plasminogen activation initiated by single-chain urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Potentiation by U937 monocytes. J Biol Chem 264: 2185–2188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman DA, Kearns A, Larsh S, Enghild JJ, Stack MS 1999. Autocrine regulation of growth stimulation in human epithelial ovarian carcinoma by serine-proteinase-catalysed release of the urinary-type-plasminogen-activator N-terminal fragment. Biochem J 341: 765–769 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grügelsiepe H, Schoen A, Kirsebom LA, Hartmann RK 2005. Enzymatic RNA synthesis using Bacteriophage T7 RNA Polymerase. In Handbook of RNA biochemistry (ed. Hartmann R et al. ), pp. 3–21 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co; KGaA, Weinheim, Germany [Google Scholar]

- Harris L, Fritsche H, Mennel R, Norton L, Ravdin P, Taube S, Somerfield MR, Hayes DF, Bast RC Jr 2007. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 25: 5287–5312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillig T, Engelholm LH, Ingvarsen S, Madsen DH, Gardsvoll H, Larsen JK, Ploug M, Dano K, Kjoller L, Behrendt N 2008. A composite role of vitronectin and urokinase in the modulation of cell morphology upon expression of the urokinase receptor. J Biol Chem 283: 15217–15223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huai Q, Mazar AP, Kuo A, Parry GC, Shaw DE, Callahan J, Li Y, Yuan C, Bian C, Chen L, et al. 2006. Structure of human urokinase plasminogen activator in complex with its receptor. Science 311: 656–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PH, Christensen EI, Ebbesen P, Gliemann J, Andreasen PA 1990. Lysosomal degradation of receptor-bound urokinase-type plasminogen activator is enhanced by its inhibitors in human trophoblastic choriocarcinoma cells. Cell Regul 1: 1043–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M, Thomas KS, Wu L, Gonias SL 2003. Soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor inhibits cancer cell growth and invasion by direct urokinase-independent effects on cell signaling. J Biol Chem 278: 46692–46698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo M, Thomas KS, Takimoto S, Gaultier A, Hsieh EH, Lester RD, Gonias SL 2007. Urokinase receptor primes cells to proliferate in response to epidermal growth factor. Oncogene 26: 2585–2594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasza A, Petersen HH, Heegaard CW, Oka K, Christensen A, Dubin A, Chan L, Andreasen PA 1997. Specificity of serine proteinase/serpin complex binding to very-low-density lipoprotein receptor and α2-macroglobulin receptor/low-density-lipoprotein-receptor-related protein. Eur J Biochem 248: 270–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenan DJ, Keene JD 1999. In vitro selection of aptamers from RNA libraries. Methods Mol Biol 118: 217–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knoop A, Andreasen PA, Andersen JA, Hansen S, Laenkholm AV, Simonsen AC, Andersen J, Overgaard J, Rose C 1998. Prognostic significance of urokinase-type plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in primary breast cancer. Br J Cancer 77: 932–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz V, Reuning U, Kruger A, Luther T, von Steinburg SP, Graeff H, Schmitt M, Wilhelm OG, Magdolen V 2001. High level synthesis of recombinant soluble urokinase receptor (CD87) by ovarian cancer cells reduces intraperitoneal tumor growth and spread in nude mice. Biol Chem 382: 789–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Webb DJ, Jo M, Gonias SL 2001. Endogenously produced urokinase-type plasminogen activator is a major determinant of the basal level of activated ERK/MAP kinase and prevents apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. J Cell Sci 114: 3387–3396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen JB, Dupont DM, Andersen TB, Nielsen AF, Sang L, Brix DM, Jensen JK, Broos T, Hendrickx ML, Christensen A, et al. 2010. RNA aptamers as conformational probes and regulatory agents for plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Biochemistry 49: 4103–4115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews DH, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner DH 1999. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol 288: 911–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May AE, Kanse SM, Lund LR, Gisler RH, Imhof BA, Preissner KT 1998. Urokinase receptor (CD87) regulates leukocyte recruitment via β2 integrins in vivo. J Exp Med 188: 1029–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DH, Catling AD, Webb DJ, Sankovic M, Walker LA, Somlyo AV, Weber MJ, Gonias SL 1999. Myosin light chain kinase functions downstream of Ras/ERK to promote migration of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-stimulated cells in an integrin-selective manner. J Cell Biol 146: 149–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nykjaer A, Kjoller L, Cohen RL, Lawrence DA, Garni-Wagner BA, Todd RF 3rd, van Zonneveld AJ, Gliemann J, Andreasen PA 1994. Regions involved in binding of urokinase-type-1 inhibitor complex and pro-urokinase to the endocytic α2-macroglobulin receptor/low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. Evidence that the urokinase receptor protects pro-urokinase against binding to the endocytic receptor. J Biol Chem 269: 25668–25676 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestourie C, Tavitian B, Duconge F 2005. Aptamers against extracellular targets for in vivo applications. Biochimie 87: 921–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen HH, Hansen M, Schousboe SL, Andreasen PA 2001. Localization of epitopes for monoclonal antibodies to urokinase-type plasminogen activator: Relationship between epitope localization and effects of antibodies on molecular interactions of the enzyme. Eur J Biochem 268: 4430–4439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploug M 2003. Structure-function relationships in the interaction between the urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor. Curr Pharm Des 9: 1499–1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnati M, Guttinger M, Valcamonica S, Sidenius N, Blasi F, Fazioli F 1996. Proteolytic cleavage of the urokinase receptor substitutes for the agonist-induced chemotactic effect. EMBO J 15: 1572–1582 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckman J, Green LS, Beeson J, Waugh S, Gillette WL, Henninger DD, Claesson-Welsh L, Janjic N 1998. 2′-Fluoropyrimidine RNA-based aptamers to the 165-amino acid form of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165). Inhibition of receptor binding and VEGF-induced vascular permeability through interactions requiring the exon 7-encoded domain. J Biol Chem 273: 20556–20567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeldal S, Larsen JV, Pedersen KE, Petersen HH, Egelund R, Christensen A, Jensen JK, Gliemann J, Andreasen PA 2006. Binding areas of urokinase-type plasminogen activator-plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 complex for endocytosis receptors of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family, determined by site-directed mutagenesis. FEBS J 273: 5143–5159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skrypina NA, Savochkina LP, Beabealashvilli R 2004. In vitro selection of single-stranded DNA aptamers that bind human pro-urokinase. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 23: 891–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tressler RJ, Pitot PA, Stratton JR, Forrest LD, Zhuo S, Drummond RJ, Fong S, Doyle MV, Doyle LV, Min HY, et al. 1999. Urokinase receptor antagonists: Discovery and application to in vivo models of tumor growth. APMIS 107: 168–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulisse S, Baldini E, Sorrenti S, D'Armiento M 2009. The urokinase plasminogen activator system: A target for anti-cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 9: 32–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan C, Huang M 2007. Does the urokinase receptor exist in a latent form? Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 1033–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker M 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 31: 3406–3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]