Abstract

Dicer is a member of the double-stranded (ds) RNA-specific ribonuclease III (RNase III) family that is required for RNA processing and degradation. Like most members of the RNase III family, Dicer possesses a dsRNA binding domain and cleaves long RNA duplexes in vitro. In this study, Dicer substrate selectivity was examined using bipartite substrates. These experiments revealed that an RNA helix possessing a 2-nucleotide (nt) 3′-overhang may bind and direct sequence-specific Dicer-mediated cleavage in trans at a fixed distance from the 3′-end overhang. Chemical modifications of the substrate indicate that the presence of the ribose 2′-hydroxyl group is not required for Dicer binding, but some located near the scissile bonds are needed for RNA cleavage. This suggests a flexible mechanism for substrate selectivity that recognizes the overall shape of an RNA helix. Examination of the structure of natural pre-microRNAs (pre-miRNAs) suggests that they may form bipartite substrates with complementary mRNA sequences, and thus induce seed-independent Dicer cleavage. Indeed, in vitro, natural pre-miRNA directed sequence-specific Dicer-mediated cleavage in trans by supporting the formation of a substrate mimic.

Keywords: RNA guide, Dicer, pre-miRNA, RNAi, rational design, endoribonuclease

INTRODUCTION

In most eukaryotes, selective RNA degradation is achieved, at least in part, by the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) via the process of RNA interference (RNAi) (Sashital and Doudna 2008). In this process, RNA duplexes are cleaved by the dsRNA-specific ribonuclease Dicer, and the cleavage products are loaded into the RISC complex to either cleave or inhibit the translation of target RNAs possessing complementary sequences. Accurate identification of the target RNA by the RNAi machinery is very important as any unintended degradation of closely related RNAs may lead to severe growth defects (i.e., off-target degradation). The selection of target RNAs by the RISC complex is achieved mainly by sequence complementarity between one of the two strands of either the siRNA or the miRNA and the target sequence.

Factors influencing the Dicer selection of the dsRNAs that trigger the RISC-dependent degradation process remain unclear. In vivo, Dicer substrates are highly structured pre-miRNAs that exhibit an interrupted 20–23-bp stem terminated by a 2 nucleotide (nt) long 3′-overhang. Substrate recognition is initiated by the interaction of the Piwi Argonaute Zwille (PAZ) domain of Dicer with this 2-nt 3′-end overhang and is stabilized by additional interactions with the 7-nt phosphodiester backbone of the overhang-containing strand (Ma et al. 2004). The unique center formed by the two catalytic domains (RNase IIIa and IIIb) is localized ∼65 Å from the 3′-end, a distance ∼25 nt away, thereby dictating the site of cleavage (Zhang et al. 2004; Cook and Conti 2006; MacRae and Doudna 2007). Dicer also possesses a dsRNA binding domain (dsRBD) that is not essential for the cleavage of canonical RNA substrates (Zhang et al. 2004) but may contribute to the stability of the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex. The function of the other Dicer domains (i.e., Helicase/ATPase and DUF 283) in the cleavage mechanism remains elusive.

It has previously been shown that both the miRNAs and the siRNAs may miss their intended targets and instead undergo partial base-pairing with other cellular RNAs, leading to their subsequent degradation. The resulting off-target effects may have major consequences on cell function and may hinder the interpretation of rationally designed gene knockdown strategies (Svoboda 2004). The existence of these off-targets is inherent to miRNA and siRNA because of the short sequences that are used to pair with the target sequence. The substrate specificity of these RNAi effectors are defined by 7 nt located in positions 2–8 of their thermodynamically unstable 5′-ends, positions that form the “seed region” (Grimson et al. 2007). It is now accepted that the specificity of the RISC complex is defined not only by RNAi pairing, but also through both protein chaperones and target sequence availability (Li et al. 2007; Carbonell et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2008; Ahmed et al. 2009; Hu et al. 2009; van Mil et al. 2009). In contrast, very little is known about the impact of Dicer or the initial pre-miRNA processing steps on the fidelity of the RNAi machinery.

This study evaluates the substrate specificity of the human Dicer enzyme and examines its capacity to directly cleave partial dsRNA substrates in trans, all with the goal of identifying non-canonical pairings that could influence the fidelity of pre-miRNA processing and function. The results indicated that Dicer may directly cleave a short dsRNA region formed in trans with high sequence fidelity using stems terminating with 3′-end overhangs as a guide. This suggests that Dicer cannot differentiate between the intramolecular duplexes naturally formed within pre-miRNAs and those that could be generated through intermolecular interactions of the pre-miRNA with cellular mRNAs possessing complementary sequences. Indeed, pairing between natural pre-miRNA and cellular mRNA was shown to lead to Dicer cleavage that aborted both the natural maturation pathway of pre-miRNA and the off-target degradation of the mRNA. Together, these results suggest that Dicer has the potential to degrade RNA in trans independent of the RISC complex, and that pre-miRNA may participate in RNA cleavage.

RESULTS

Short single-stranded RNA guides sequence and position dependent cleavage by Dicer

Unlike most members of the dsRNA-specific RNase III family, Dicer predominantly cleaves substrates terminating with 3′-end overhangs. The recognition of the unpaired end is achieved by the PAZ domain (MacRae et al. 2006; Sashital and Doudna 2008), and not by the dsRBD that is normally used by RNase III for initial interaction with the substrate as seen with bacterial (Calin-Jageman et al. 2001; Gan et al. 2006, 2008; Hallegger et al. 2006; Meng and Nicholson 2008) and yeast RNase III (Nagel and Ares 2000; Lamontagne and Abou Elela 2004; Wu et al. 2004). This suggests that the 3′-end overhang is sufficient for substrate selection by Dicer. This hypothesis was tested by synthesizing a series of short (25 nt) single-stranded RNAs with sequence complementarities in order to both fix long single-stranded RNA targets (LS) and monitor their capacity to induce cleavage by Dicer (Fig. 1A). As shown in Figure 1B (left panel), short 25-nt single-stranded RNAs induced long target-dependent cleavage when their pairing with the long target creates a 3′-end overhang on either the effector (RG-1) or target strand (RG-3). As expected, an internal pairing that created a 25-bp perfect RNA duplex was not cleaved by Dicer (RG-2), while cleavage did occur with a shorter RNA target (SS) that created a 3′-overhang with the same oligoribonucleotide (Fig. 1B, right panel). In addition, if a flanking 2 nt of 3′-overhang was added at the extremity of the RG-2 that was paired with the LS, cleavage was not observed (data not shown). These results indicate that short single-stranded RNA can guide sequence-specific Dicer-mediated cleavage in a 3′-end overhang-dependent manner, and that the primary Dicer binding site must be located at the end of a stem.

FIGURE 1.

Reconstitution of Dicer substrates in trans using short single-stranded RNAs. (A) Schematic representation of the short single-stranded RNA guides (RG, in gray) used to target the Dicer cleavage in B. The positions of the observed cleavage sites are indicated by the arrows along the target (black line). The nonproductive oligoribonucleotide is marked with an X. (*) The position of the 5′-32P. (B) Different single-stranded RNAs (RG1-3) were incubated with either 5′-end-labeled 151-nt-long single-stranded RNA (LS) or short 70-nt single-stranded RNA (SS) (both derived from the Caspase 8 mRNA) in either the presence (RG-X) or absence (Cont) of specific guides. The positions of the input substrates (LS or SS), as well as of the cleavage products (P1-3), are indicated. The percent cleavage for each reaction is indicated at the bottom. (C) Formation of perfect RNA duplexes is not required for Dicer cleavage. Substrates carrying insertions of 4–15 nt upstream of the predicted cleavage sites were generated and tested for cleavage in vitro (D). (Gray boxes) The positions of the predicted cleavage sites; (arrows) the observed cleavage sites. (S) Input substrates; [P(4-8)] the products. The cleavage velocities relative (Rel) to that of the unmutated substrate (RG-4) are shown at the bottom. All experiments are repeated at least three times with a maximum error of the rate of +0.05.

Since natural Dicer substrates (e.g., pre-miRNAs) are rarely formed from fully paired RNA stems, the impact of introducing base mispairing on the capacity of the effector RNA to guide Dicer cleavage was tested. In this case, the effector length was kept constant, and various sequences complementary to the target RNA were synthesized, each carrying a 4-nt to 15-nt insertion at the predicted Dicer cleavage site (Fig. 1C). As shown in Figure 1D, the insertion of 4 nt (RG-5) and 6 nt (RG-6) moderately reduced the cleavage rate and shifted the cleavage site by 4 nt and 6 nt, respectively. On the other hand, insertions of 10 nt (RG-7) and 15 nt (RG-8) not only shifted the cleavage site by the same number of nucleotides, but also significantly reduced the cleavage rate. These data indicate that Dicer acts as a helical ruler counting base-paired nucleotides from the 3′-end overhang and that it can tolerate small asymmetrical bulges.

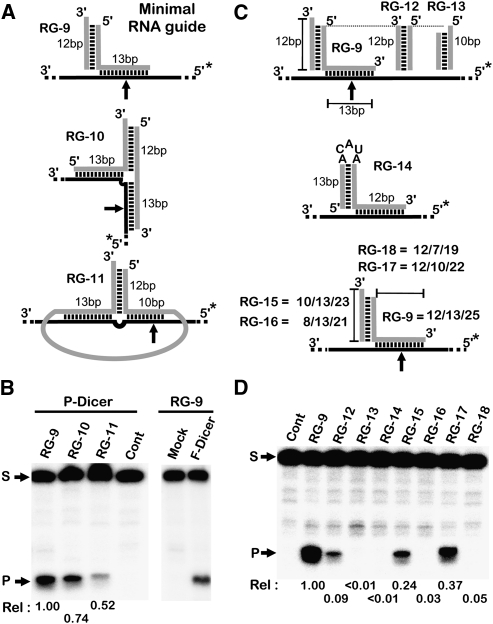

Guiding Dicer cleavage with a fixed primary binding site

The fact that a 3′-overhang may direct Dicer-mediated cleavage at a fixed distance, regardless of the target sequence's length, suggests that Dicer binding and cleavage are independent processes that could be separated into distinct steps. In order to test this hypothesis, a 12-bp RNA stem (binding beacon) terminating with a 3′-end overhang that could bind, but not be cleaved, by Dicer, was created and attached to a 13-nt single-stranded RNA guide (RG-9) that could be used to bind any target possessing complementary sequence (Fig. 2A). As shown in Figure 2B, this RNA guide induced robust internal cleavage within the target RNA despite the long distance from the target's termini. This cleavage was both guide-dependent (Fig. 2B) and target-dependent (data not shown). The guide's cleavage was not related to a specific Dicer preparation, as cleavage by both partially purified and immunoprecipitated Flag-tagged enzymes was observed (Fig. 2B, P- and F-Dicer, respectively). This demonstrates that the guide RNA may target Dicer cleavage to any internal mRNA sequence in trans by forming only 13 bp with the target sequence. Surprisingly, neither increasing the number of paired bases (data not shown) nor the formation of a symmetrical binding site (RG-10) with the target enhanced the rate of cleavage (Fig. 2A,B). Interestingly, producing the effector RNA in cis by joining the guiding strands (RG-11), as would be the case for any potential natural RNA guides (e.g., pre-miRNA), supported cleavage. As expected, the elimination of the 3′-overhang of the effector RNA (i.e., RG-12, RG-13, and RG-14) either greatly reduced, or abolished, the cleavage (Fig. 2C,D). Decreasing the size of the binding beacon to 10 bp (RG-15) reduced the level of cleavage, while reducing it further to 8 bp (RG-16) abolished cleavage. Similarly, reducing the guiding RNA to either 7 or 10 bases (RG-18 and RG17) reduced or inhibited cleavage, respectively, suggesting that a total of 25 bp is required for optimal cleavage. Together, these data prompt the conclusion that substrate binding and cleavage by Dicer are not obligatorily coupled, but instead a single binding site may target cleavage to a variety of targets.

FIGURE 2.

Directing Dicer cleavage using a fixed binding site. (A) Schematic representation of the different RNAs (in gray) used to guide Dicer cleavage in trans. An RNA stem with a fixed sequence terminating in a 3′-overhang was fused to single-stranded RNA fragments capable of forming either a short RNA duplex (RG-9), a long RNA duplex (RG-10), or a long RNA duplex with joined termini (RG-11) with a common target sequence. (*) The position of the 5′-32P. (B) The different RNA guides illustrated in A were incubated with 5′-end-labeled target RNA (black line) derived from the Caspase 8 mRNA and partially purified commercial Dicer protein (P-Dicer) in either the absence (Cont) or the presence of the corresponding guide. Cleavage of the RNA substrates was also performed using immunoprecipitated Flag-tagged Dicer (F-Dicer), and a mock precipitation was included as a control (i.e., RG-9 was presented in both reactions). (C) Schematic representation of the different RNA molecules designed to characterize the features of the RNA stem required to guide Dicer cleavage in trans. (D) The RNA target complexes with guide RNAs (from C) were incubated with partially purified Dicer as described in B. (S) Position of the substrate; (P) position of the cleavage product. The relative velocities (Rel) are indicated at the bottom. All experiments were repeated at least three times with a maximum error of the rate of +0.05.

Selective effects of 2′-OMe on Dicer primary binding

Most members of the RNase III family interact with their substrates by forming hydrogen bonds with the 2′-OH of the RNA. Consequently, these enzymes can sense any changes to both the major and minor grooves, a phenomenon that has previously been shown to affect the substrate specificities of most dsRNA substrates (Nicholson 1999; Lamontagne et al. 2001). Therefore, it is of interest to examine the impact of the 2′-OH on Dicer substrate selection, as well as the capacity of the RNA guide to direct Dicer-mediated cleavage. A series of guide RNAs with various 2′-OMe substitutions was produced and tested for cleavage using a fixed target (Fig. 3A,B). The position of these modifications was chosen not to affect RNA duplex formation or the overall substrate structure based on previous study using yeast and bacterial RNase III (Lamontagne et al. 2004; Lamontagne and Abou Elela 2007; Lavoie and Abou Elela 2008). Surprisingly, all 2′-OMe substitutions were tolerated except for that located at the cleavage site (see RG-20 result). Together, the results of RG-19, -20, and -21 suggest that the integrity of the ribose 2′-OH is not required for Dicer binding, but instead is crucial for either the formation of the catalytic core (i.e., the region of the cleavage site complexed with the RNase III domain) or the cleavage chemistry. In order to differentiate between these two possibilities, single 2′-OMe substitutions were introduced near the cleavage site. As summarized in Figure 3C, single substitutions near the scissile bond (RG-9) in either the target or guiding strands strongly inhibited cleavage. However, it is important to note that substitutions as far as 4 nt away from the scissile bond inhibited cleavage, suggesting that hydrogen-bonding is required for formation of the active substrate–enzyme and not for the cleavage chemistry (RG-22). Indeed, simultaneous mutations near the scissile bond and the guide strand (RG-22) restored cleavage at a new site, supporting the idea that the introduction of 2′-OMe alters the substrate–enzyme complex.

FIGURE 3.

Effect on reactivity of 2′-OMe groups into the primary Dicer binding site. (A) The impact of the 2′-OH groups on substrate selection and cleavage by Dicer was examined. Different RNA oligonucleotides were synthesized with 2′-OMe substitutions in the Dicer binding site (RG-19), within the guide sequence (RG-20), or in both binding and guide sequences (RG-21). (Green lines) RNA sequences present in the RG; (blue lines) the sequences containing the 2′-OMe groups; (*) the position of the 5′-32P. (B) Cleavage reactions were conducted as described in Figure 2 using 5′-end-labeled substrates as targets (black line). (Rel) The cleavage velocities relative to that obtained with RG-9. The values shown represent the average of at least two experiments with a maximum error of the rate of +0.05. (S) Position of the substrate; (P) positions of the products. (C) Summary of the cleavage activities obtained with various RNA guides carrying either single or multiple 2′-OMe groups near the Dicer cleavage site. (Red) The position of the 2′-OMe group; (arrowheads) the positions of Dicer cleavage; (black arrows) strong cleavage; (open arrows) medium cleavage; (gray arrows) weak cleavage. For clarity, the fixed binding sites were drawn only for the first three examples.

RNA guides direct sequence-dependent cleavage

In order to demonstrate the base-pairing contribution to Dicer-mediated cleavage, different guide RNAs possessing either single or multiple base mismatches in either the binding beacon or the guiding strand were generated (Fig. 4A, left panel). Interruption of the guiding beacon helix by one or two mismatches only moderately reduced the level of cleavage (i.e., RG-24, RG-25, and RG-26), while even the presence of a single nucleotide mismatch near the scissile bond abolished cleavage (RG-27) (Fig. 4A, right panel). This suggests that the enzyme may tolerate interruption in the RNA helix as previously demonstrated for other eukaryotic RNase III's (Chelladurai et al. 1993; Schweisguth et al. 1994; Lamontagne and Abou Elela 2004, 2007).

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of Dicer-dependent RNA-guided cleavage. (A) The presence of a single base mismatch on the binding arm of the guide abolishes Dicer cleavage. Various Dicer RNA guides (in gray) carrying mutations that disrupt base-pairing in either Dicer binding site, or in the targeting sequence (left panel), were synthesized and tested for cleavage using a 5′-end-labeled target RNA as described in Figure 2 (right panels). (*) The position of the 5′-32P. (S) The positions of the input substrates; (P) the positions of the cleavage products. (B) Short duplex RNAs direct precise site-specific cleavage. RNA guides (in gray) targeting different positions in a single target RNA (black line, left panel) were synthesized and tested for cleavage (right panel) as described in A. The target RNA was incubated in the presence of partially purified Dicer and the strand guide harboring the binding arm in either the presence (+) or the absence (−) of the complementary Univ strand forming the 3′-overhang stem. For the control condition (Cont), the RG is missing, and for the Univ condition, the binding arm strand was omitted. The positions and the names of the guide RNAs driving the cleavage are shown on the left of the gel. (Rel) The cleavage velocities relative to that obtained with RG-9, represents the average of at least two experiments with a maximum error of the rate of +0.05.

The precision of the guide-dependent Dicer cleavage was further demonstrated by creating guide RNAs that target different cleavage sites within a single RNA target and then testing them for cleavage. As shown in Figure 4B, cleavage at the precise nucleotide targeted by the guide RNA was detected in each case. This is an unambiguous demonstration of the precision of the guide sequence.

MiRNA-like structure directs Dicer cleavage

In vivo, the most likely RNAs that may elicit the Dicer-mediated, RNA-guided cleavage developed in vitro are the miRNAs that are naturally produced as part of the RNAi machinery. Consequently, it is of interest to verify whether or not an miRNA mimic can guide Dicer cleavage in trans. Guide RNAs were produced with extended paired 5′- and 3′-ends formed either in trans (RG-34) or in cis (RG-35), and were tested for cleavage activity (Fig. 5A,B). Cleavage was obtained only when sufficient pairing between the guide and the target RNA occurred (B1-B2-K, lane 1), disrupting the internal pairing within the guide itself. Simply disrupting the internal pairing of the guides also led to cleavage (B1-B2, lane 4). The pairing requirement was similar for both the cis (RG-34) and trans (RG-35) guide RNAs. Together, the results indicate that complex RNA structures with extensive base-pairing similar to miRNA could guide Dicer-mediated cleavage in trans.

FIGURE 5.

A micro-RNA-like structure guides Dicer cleavage in vitro. (A) Representations of the different designs of the RNA guides produced in order to test whether or not an miRNA-like structure may drive Dicer cleavage in vitro. The miRNA-like guide RNAs are shown either in the absence (on top), or the presence (at bottom), of the target RNA (black line). B1 (blue), B2 (yellow), and K (red) indicate, respectively, the binding arm or the equivalent of the seed sequence in an miRNA, the strand complementary to the target site, and the sequence pairing with the binding arm. RG-34 mimics the structure of a mature miRNA, while RG-35 represents a short version of a pre-miRNA. (*) The position of the 5′-32P. (B) RNA cleavage using an miRNA-like construct as guide. The miRNA-like guide RNAs, which contain either the good corresponding sequences (+) or unrelated sequences (−), were incubated with the 5′-end-labeled RNA target. (Rel) The cleavage velocities relative to that obtained with RG-9, represents the average of at least two experiments with a maximum error of the rate of +0.05.

Examining the ability of pre-miRNA to direct Dicer cleavage in vitro

Based on the fact that an miRNA mimic may target Dicer cleavage in trans, a natural miRNA that could direct Dicer cleavage in vivo was searched for. The potential miRNA guide must possess sufficient base-pairing to bind a target RNA while also preserving the integrity of the 3′-end overhang for Dicer-mediated cleavage. These features are present in complexes that could form between pre-miRNA structures and matching mRNA sequences. In this hypothesis an mRNA strand would invade the structure of pre-miRNA, preventing it from being naturally processed by Dicer, and instead the invading mRNA strand would be cleaved in trans (Fig. 6A, Off-target mechanism). In order to test this hypothesis, the miRBase database was screened (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/sequences/) for pre-miRNAs that possess several bulges and a large loop that would facilitate any potential binding with an RNA molecule in trans. Several pre-miRNAs (more than 20 species) with varying degrees of compliance with the search criteria were found, and the miRNA precursor (hsa-pre-mir-500) was selected in order to test for cleavage in vitro. As shown in Figure 6B (P-Dicer), Dicer processed the 5′-end 32P-labeled pre-miRNA substrate as expected, producing mature miRNA (P1) and a fragment corresponding to the processing waste (P2). Chemical mapping of the cleavage products confirmed that the cleavage occurred at the predicted site located 28 nt from the 3′-overhang stem of the 5′-end strand (data not shown). The cleavage took place with the pseudo-first-order constant (kcat/KM) of 0.24 μM−1 min−1, which is in good agreement with the previously established kinetic parameters of Dicer (Ma et al. 2008). The same cleavage pattern was observed regardless of the method used to purify Dicer, suggesting that the cleavage activity is specifically associated with the enzyme (Fig. 6B, P-Dicer vs. F-Dicer). Incubation of the pre-miRNA with the long unlabeled T7 RNA target sequence completely inhibits the pre-miRNA processing (Fig. 6B, lane 10X). These results confirm that Dicer can faithfully recognize and process its natural pre-miRNA targets.

FIGURE 6.

Seed-independent pairing of pre-miRNA with mRNA induces Dicer dependent RNA degradation. (A) Schematic representation of the natural processing pathway of the hsa-pre-miR-500 (upper part), and a possible alternative target mRNA-independent degradation pathway (lower part). Oligoribonucleotides carrying the natural hsa-pre-miR-500 sequence were synthesized with 3 nt near the 3′-end mutated in order to allow for run-off transcription (blue circles). The blue and orange strands correspond to the target binding arms. In the left panel, the sites of Dicer cleavage are indicated by arrows (sites 1 and 2 produce P1 and P2 in B). (Black line) The RNA target. (*) The position of the 5′-32P. (B) Dicer accurately processes hsa-pre-mir-500 in vitro. 5′-End labeled hsa-pre-mir-500 (pm) was incubated in either the absence (−) or the presence (+) of partially purified Dicer (P-Dicer), or was incubated with immunoprecipitated Flag-tagged Dicer (F-Dicer). The cleavage reaction was also performed in the presence of a 10× excess of the target sequence complementary to the binding arms of the hsa-pre-mir-500 (10×). The pre-miRNA cleavage products (P1 and P2) are indicated. (C) Pre-miRNA targets Dicer cleavage to long RNA fragments in vitro. The hsa-pre-mir-500 was incubated with a 5′-end-labeled 151-nt-long RNA (S) carrying a sequence complementary to either the binding arms of the miRNA (Target, lane 1) or an unrelated sequence (US, lane 4). (P) The target product. In lane 2, the target and the pre-miRNA were both labeled. The mature miRNA produced by Dicer cleavage was incubated with the long RNA target in lane 3. The results shown are representative of at least two independent experiments. (Open triangle) An unidentified cleavage product.

Finally, the impact of incubating the natural pre-miRNA, hsa-pre-mir-500, with a 5′-end-labeled 151-nt-long transcript as target, was verified (Fig. 6C; Huttenhofer and Schattner 2006). The RNA target, harboring a modified sequence to accommodate pre-miRNA-500 binding, was specifically cleaved when it was incubated with the unlabeled pre-miRNA (Fig. 6C, lane 1). When both the target and the pre-miRNA were labeled with 32P and incubated together (Fig. 6C, lane 2), cleavage was again observed, more specifically two independent Dicer-mediated cleavage events were observed. One was of the long target, while the other was of the pre-miRNA (the products of these cleavages are indicated on the left and right side of the autoradiogram, respectively). These reactions induced additional cleavages in the target independent of the complementarity between the target and the miRNA seed sequence usually involved in translation inhibition. Incubation of the target RNA with a guide RNA that resembles the mature miRNA sequence also induced cleavage in the target (Fig. 6C, lane 3), but at a different site (1 nt upstream) and to a lower level, indicating that pre-miRNA is more likely to induce off-target cleavage than is mature miRNA. Together, these results clearly demonstrate that Dicer may use different combinations of RNA structures in trans in order to increase its repertoire of substrates. The data also suggest that the abundance of complementary transcripts may regulate the amount of miRNA produced in the cell by inhibiting the processing of pre-miRNA by Dicer.

DISCUSSION

The crystal structure of the Giardia intestinalis has revealed that the PAZ domain is separated from the two catalytic RNase III domains by a distance that matches 25-bp-long RNA helix (MacRae et al. 2006). Accordingly, it was proposed that the Dicer cleavage site is determined by the distance from the PAZ domain binding site at the terminal 3′-overhang. This so-called helical ruler model explains how Dicer cleaves at a fixed distance from the substrate 3′-end and suggests that PAZ domain binding is the primary criterion for substrate selection. In agreement with this model, we have shown in this study that, indeed, the insertion of base pairs downstream from the substrate 3′-end overhang respectively displaces the cleavage position and the deletion of overhang blocks cleavage. Most interestingly, we demonstrated that a short RNA stem structure terminating with a 3′-overhang is sufficient for directing cleavage by the human RNase III (Dicer) in trans. Substrate cleavage was blocked by modification of the 2′-hydroxyl groups at the site of cleavage and not when introduced within the PAZ binding site, suggesting that hydrogen bonds play a minor role in substrate recognition. Indeed, consultation of the PAZ domain/RNA structure suggests that PAZ uses a relatively flexible binding mode where the 3′-end is accommodated in a binding pocket supported by an RNA backbone contact that spans 7 nt (Ma et al. 2004; Yuan et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2008a,b, 2009). Finally, the capacity of Dicer to cleave RNA formation in a three-way junction reported here is consistent with the conserved catalytic domain structure of RNase III that forms an open valley or tube allowing the binding of one of the two alternative helices that may form by RNA carrying a three-way junction while leaving the third helix protruding in space (Franch et al. 1999; Gan et al. 2006; Lavoie and Abou Elela 2008). The flexibility of the Dicer mechanism of substrate recognition is also supported by the flexibility of the flat positively charged connecting domain linking the PAZ domain to the catalytic core.

The presence of the PAZ domain in the Dicer subfamily of RNase III raises questions about the mechanism of substrate selection and the role of the classical dsRNA binding domain in RNA binding and cleavage by this enzyme. Earlier studies using short 21–27-nt RNA duplexes suggested that chemical modifications of the 3′-overhang, and excessive modification of dsRNA itself, may affect cleavage by Dicer. However, these studies did not differentiate between the Dicer and Slicer activities, both of which are required for silencing in vivo (Collingwood et al. 2008). The use of a bipartite substrate clearly demonstrated that the 2′-OH of the 3′-end overhang that is recognized by the PAZ domain may be replaced with a 2′-OMe with no noticeable effect on cleavage (Fig. 3). Indeed, modification of all of the nucleotides except that adjacent to the scissile bond permitted cleavage. Therefore, it is likely that most of the defects in RNA silencing detected upon the substitution of the 2′-OH are due to interference with the RISC complex's slicing activity and not to Dicer cleavage (Collingwood et al. 2008). The observation that the presence of a 2′-OMe near the cleavage site either blocks, or modifies, the cleavage site raises questions about the contribution of the 2′-OH to Dicer's catalytic activity. Earlier studies using both bacterial (Robertson and Dunn 1975; Nicholson et al. 1988; Nicholson 1992) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae RNase III (Lamontagne et al. 2004), as well as the structure of G. intestinalis Dicer (MacRae et al. 2006), suggest that catalysis does not require the presence of a 2′-OH, in contrast to what is seen with RNase H (Yazbeck et al. 2002). Moreover, it appears that it is the introduction of a bulky group, rather than the absence of the 2′-OH, that inhibits the cleavage (Lamontagne et al. 2004; Gan et al. 2005, 2006, 2008; MacRae et al. 2006; MacRae and Doudna 2007). Therefore, it is likely that the cleavage block observed in this study was caused by steric hindrance of the formation of the catalytic core. This conclusion is consistent with comprehensive chemical modification and probing of other RNase III's like that of yeast and bacteria (Nicholson et al. 1988; Nicholson 1992; Chelladurai et al. 1993; Li et al. 1993; Lamontagne et al. 2004; Lavoie and Abou Elela 2008). In those cases, introduction of 2′-OMe blocked cleavage, while substitution for the ribonucleotide vicinal to the scissile phosphodiester linkage with 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoro-β-D-ribose (2′ F-RNA) did not, confirming that the 2′-OH is not required for cleavage (Lamontagne et al. 2004; Lavoie and Abou Elela 2008).

The newly developed Dicer RNA guides consist of a 12-bp binding arm and a minimum of a 13-base-long guiding arm complementary to the target RNA. Upon binding to the target, the RNA guide forms a bipartite substrate with two stems that could be stacked together to mimic an RNA duplex. Stacking of these RNA stems appears to be important for efficient RNA cleavage by Dicer. Indeed, guide RNA that forms a three-way junction results in a less efficient cleavage, and covalently linking the two binding arms together by a single-stranded RNA linker further reduces the cleavage efficiency (Fig. 2). It is possible that the presence of a three-way junction impedes the formation of a catalytically competent enzyme–substrate complex by sterically hindering the correct positioning of the cleavage site in the enzyme's catalytic core (i.e., RNase III domains). Interestingly, the stability of the guide/target RNA complex did not greatly affect cleavage efficiency, since the use of a stable RNA complex (as judged by electrophoresis mobility shift assay) did not always produce robust cleavage (data not shown). One explanation of this phenomenon is that Dicer binding itself stabilizes the complex formed between the guide and the target RNA, while increased stability of the bipartite complex reduces product release. Previous studies using yeast RNase III indicated that strengthening the RNA duplex formation by increasing the GC content often leads to an increase in the binding affinity and a decrease in the catalytic rate (Lamontagne et al. 2003).

All RNase III's, including Dicer, normally introduce two staggered cleavage sites on each side of their canonical RNA substrates. However, in the case of RNA-guided cleavage, we have consistently observed that Dicer introduces a single cut in the target RNA located at 20 bp upstream of the 3′-overhang and on the other strand, even in cases when the guide RNA contained two binding arms and generated two potential cleavage sites. This suggests that either Dicer prefers one particular conformation of the different conformations adopted by the RNA guide/target three-way junctions, or that the enzyme itself induces a specific RNA fold once it binds the 3′-overhang. Looking at the Giardia Dicer crystal structure, it is tempting to speculate that the two Dicer selected stems (3′-overhang and the binding arm strand) stack together and bind to the flat linker surface in between the PAZ and the RNase domains (MacRae et al. 2006) leaving the third stem protruding from the nuclease domain in space. A comparable asymmetric cleavage was also reported when the cleavages of yeast RNase III (Rnt1p) and tRNase ZL were directed in trans using guide RNA (Lamontagne and Abou Elela 2007; Nakashima et al. 2007). Therefore, it is likely that this phenomenon is not specific to any given cleavage mechanism, but rather that it demonstrates the inherently limited number of three-way junction conformations that could correctly fit for catalysis.

Traditionally, the miRNA mechanism of action is predicted by monitoring the complementarities between the so-called seed sequences of the miRNAs and the potential targets. This study shows that Dicer may directly cleave RNA complexes formed between a pre-miRNA and a model RNA target independent of the seed sequence, leading to an off-target (Fig. 6). This suggests that this enzyme may cleave a much broader repertoire of substrates than previously thought. This cleavage is possible because of the natural formation of a 3′-overhang near the transcript end of the majority of the pre-miRNAs (Carmell and Hannon 2004) that could be used as a target for cleavage in trans once invaded by an external RNA. Interestingly, the cleavage directed by a natural miRNA occurs 19–20 bp from the 3′-overhang, and not the 21–22 bp observed with canonical substrates (data not shown). This reduction in the distance probably reflects the unusual folding of the three-way junction located at the bottom of the cleaving stem.

The capacity of pre-miRNA hsa-pre-mir-500 to direct cleavage by Dicer in trans suggests a potential new role for pre-miRNA in the regulation of nuclear transcripts. A search for complementarity between pre-miRNAs and potential RNA transcripts in the human genome revealed several potential pre-miRNA-dependent targets (data not shown). This suggested that in trans directed Dicer cleavage may play an important role in regulating RNA expression in human cells. It will be very instructive to verify this hypothesis, although it is not a trivial experiment since the unstable pre-miRNA/target complex forms only transiently in the cell, and measuring the impact on any given nuclear RNA target may be concealed by the majority of cytoplasmic RNA transcripts that constitute the bulk of cellular RNA at any given moment. Moreover, it is believed that pre-miRNAs are processed either from mirtrons (Ruby et al. 2007) or introns encoding pri-miRNA (Berezikov et al. 2007), or from either independently transcribed long transcripts or a cluster of transcripts. Since processing of the pre-miRNA from a mirtron does not require any specific motif, it can assume a variety of conformations. The data presented here suggest the existence of an alternative pre-miRNA processing pathway in which the short mirtron may form a complex with an external RNA target and recruit Dicer for cleavage. In any case, it is becoming increasingly evident that the catalog of both potential Dicer substrates and off-target in trans cleavage by pre-miRNAs is much larger than is currently believed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Substrates and RNA guides synthesis

The 151-nt Caspase 8 substrate sequence was derived from sequence entry NM_033358 of the NCBI database (see the Supplemental Material for all of the detailed sequences). The hsa-pre-mir-500 sequence was obtained from the miRBase sequences website (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/cgi-bin/sequences/mirna_entry.pl?acc=MI0003184). The sequence of the Caspase 8 was minimally modified based on the deep sequencing prediction of the mature miRNA, and to permit efficient T7 RNA polymerase transcription (see Fig. 1; Supplemental Material). Both the RNA guides and substrates were synthesized by run off transcription from a PCR product of two annealed oligonucleotides harboring a T7 promoter, and the resulting transcripts were gel-purified. Briefly, transcriptions were performed in the presence of T7 RNA polymerase (15 μg) and either annealed oligodeoxyribonuclotides (5 μM) or a PCR product (5 μM) in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.5), 28 mM MgCl2, 40 mM DTT, 2 mM spermidine, 100 μg/mL BSA, 6 mM GTP, and 4 mM each ATP, CTP, and UTP in a final volume of 100 μL for 2–4 h at 37°C. Upon completion, the reaction mixtures were treated with RNAse RQ1 (Amersham Biosciences) for 20 min at 37°C, and the RNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. RNA products were fractionated by denaturing 10%–20% PAGE electrophoresis (19:1 ratio of acrylamide to bisacrylamide) in buffer containing 45 mM Tris-Borate (pH 7.5), 7 M urea, and 1 mM EDTA. The reaction products were visualized by UV shadowing, and the bands corresponding to the correct sizes for both the RNA guides and the substrates were cut out and the transcripts eluted overnight at room temperature. The eluted transcripts were ethanol-precipitated, washed, dried, and dissolved in water. Lastly, the transcripts were quantified by absorbance at 260 nm. Some RNA guides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. and either gel-purified or HPLC-purified.

RNA 5′-end labeling

Both substrates and guide RNAs were dephosphorylated in a final volume of 20 μL containing 50 mM Bis-Tris-Propane-HCl (pH 6.0), 1 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM ZnCl2, and 2.5 units of antarctic phosphatase (New England Biolab) for 30 min at 37°C, and were then purified by phenol-chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation. The resulting RNAs were then 5′-end labeled in a final volume of 10 μL containing 1.6 pmol of [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, NEN, PerkinElmer) and 5 units of T4 polynucleotide kinase as recommended by the manufacturer (New England Biolabs). The reaction mixtures were fractionated on denaturing PAGE gels, and the RNA species were recovered as described above.

Flag-tag Dicer immunoprecipitation

The coding sequence of human Dicer was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector, and the Flag-tag sequence (Asp-Tyr-Lys-Asp-Asp-Asp-Asp-Lys) was inserted at its N terminus. The resulting plasmid was named pcDNA3.1-5′FLAG-Dicer and was kindly provided by P. Provost (Provost et al. 2002; Lee et al. 2003). The recombinant Flag-Dicer plasmid was transfected in HEK 293T cells using 750,000 cells, 2 μg of vector, and 3 μL of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per well in 6-well dishes. The cells were collected 48 h post-transfection, resuspended in 900 μL of sonication buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH at pH 7.9, 100 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 5% glycerol) and sonicated, and the resulting mixtures were centrifuged for 20 min at 14,000 rpm. The supernatant was recovered and centrifuged for a further 5 min at 14,000 rpm. Anti-Flag M2 affinity equilibrated gel (40 μL; Sigma) was mixed with the supernatant protein extract according to the manufacturer's recommendations and then incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing the gel using the same buffer, the beads were resuspended in 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 40% glycerol solution, and the Flag-Dicer immunoprecipitate was stored at −20°C.

Dicer cleavage assays

Dicer cleavage assays were performed in a final volume of 10 μL containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.1 μg/μL of bacterial tRNA (Sigma). Initially, the two RNA strands (1 μM each) composing a guide were mixed together in a final volume of 6 μL containing water and buffer and were then incubated successively for 30 sec at 94°C followed by 5 min at 37°C in order to allow annealing to occur. A trace amount of 5′-end-labeled substrate (2 μL) was then added, and the reactions were incubated for 5 min at 37°C in order to allow binding of the RNA guide to the substrate to occur. Human recombinant Dicer enzyme (Genlantis; cat. no. T510002) was then added to a final concentration of 0.025 unit/μL (a total of 2 μL of a dilution 0.125 unit/μL solution per reaction), and the reaction was incubated for 90 min at 37°C. The reactions were stopped by adding loading dye (6 μL, 97% formamide, 10 mM EDTA at pH 8.0, xylene cyanol, and bromophenol blue) and fractionated on denaturing 12% PAGE gels that were analyzed by PhosphorImager (Storm 860; Amersham Biosciences). In all experiments, a control in which the RNA guide was omitted was included (labeled “cont” in the figures). When Flag-Dicer was used, 5 μL of the immunoprecipitate beads was added instead of the commercial Dicer preparation. RNAguard RNase inhibitor (13.8 units; Porcine, GE Healthcare) was added to these latter reactions. Upon completion, the samples were phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol-precipitated, and analyzed on PAGE gels as described above. For the relative cleavage value (Rel), the cleavage percentages of at least two independent reactions were averaged and compared to that of the C3 construct, whose latter value was arbitrarily fixed at 1.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material can be found at http://www.rnajournal.org.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Dr. M. Simard (Université Laval), Dr. B. Lamontagne, J.P. Brosseau, Dr. J.P. Venables, and the members of the Laboratoire de génomique fonctionnelle at the Université de Sherbrooke for helpful discussions; and Dr. P. Provost (Université Laval) for generously supplying the recombinant Flag-Dicer plasmid. This work was funded by both Génome Québec and Génome Canada. The RNA group is sponsored by both the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) and the Université de Sherbrooke. L.J.B. is the recipient of a CIHR post-doctoral fellowship. J.P.P. holds the Canada Research Chair in Genomic and Catalytic RNA, while S.A.E. is a Chercheur National from the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). J.P.P. and S.A.E. are members of the Centre de Recherche Clinique Étienne-Lebel. There is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.2346510.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed F, Ansari HR, Raghava GP 2009. Prediction of guide strand of microRNAs from its sequence and secondary structure. BMC Bioinformatics 10: 105 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezikov E, Chung WJ, Willis J, Cuppen E, Lai EC 2007. Mammalian mirtron genes. Mol Cell 28: 328–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin-Jageman I, Amarasinghe AK, Nicholson AW 2001. Ethidium-dependent uncoupling of substrate binding and cleavage by Escherichia coli ribonuclease III. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 1915–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell A, Martinez de Alba AE, Flores R, Gago S 2008. Double-stranded RNA interferes in a sequence-specific manner with the infection of representative members of the two viroid families. Virology 371: 44–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmell MA, Hannon GJ 2004. RNase III enzymes and the initiation of gene silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 214–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelladurai B, Li H, Zhang K, Nicholson AW 1993. Mutational analysis of a ribonuclease III processing signal. Biochemistry (Mosc) 32: 7549–7558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PY, Weinmann L, Gaidatzis D, Pei Y, Zavolan M, Tuschl T, Meister G 2008. Strand-specific 5′-O-methylation of siRNA duplexes controls guide strand selection and targeting specificity. RNA 14: 263–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood MA, Rose SD, Huang L, Hillier C, Amarzguioui M, Wiiger MT, Soifer HS, Rossi JJ, Behlke MA 2008. Chemical modification patterns compatible with high potency dicer-substrate small interfering RNAs. Oligonucleotides 18: 187–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Conti E 2006. Dicer measures up. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 190–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franch T, Thisted T, Gerdes K 1999. Ribonuclease III processing of coaxially stacked RNA helices. J Biol Chem 274: 26572–26578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan J, Tropea JE, Austin BP, Court DL, Waugh DS, Ji X 2005. Intermediate states of ribonuclease III in complex with double-stranded RNA. Structure 13: 1435–1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan J, Tropea JE, Austin BP, Court DL, Waugh DS, Ji X 2006. Structural insight into the mechanism of double-stranded RNA processing by ribonuclease III. Cell 124: 355–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan J, Shaw G, Tropea JE, Waugh DS, Court DL, Ji X 2008. A stepwise model for double-stranded RNA processing by ribonuclease III. Mol Microbiol 67: 143–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP 2007. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: Determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 27: 91–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallegger M, Taschner A, Jantsch MF 2006. RNA aptamers binding the double-stranded RNA-binding domain. RNA 12: 1993–2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HY, Yan Z, Xu Y, Hu H, Menzel C, Zhou YH, Chen W, Khaitovich P 2009. Sequence features associated with microRNA strand selection in humans and flies. BMC Genomics 10: 413 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenhofer A, Schattner P 2006. The principles of guiding by RNA: Chimeric RNA–protein enzymes. Nat Rev Genet 7: 475–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne B, Abou Elela S 2004. Evaluation of the RNA determinants for bacterial and yeast RNase III binding and cleavage. J Biol Chem 279: 2231–2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne B, Abou Elela S 2007. Short RNA guides cleavage by eukaryotic RNase III. PLoS ONE 2: e472 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne B, Larose S, Boulanger J, Abou Elela S 2001. The RNase III family: A conserved structure and expanding functions in eukaryotic dsRNA metabolism. Curr Issues Mol Biol 3: 71–78 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne B, Ghazal G, Lebars I, Yoshizawa S, Fourmy D, Abou Elela S 2003. Sequence dependence of substrate recognition and cleavage by yeast RNase III. J Mol Biol 327: 985–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamontagne B, Hannoush RN, Damha MJ, Abou Elela S 2004. Molecular requirements for duplex recognition and cleavage by eukaryotic RNase III: Discovery of an RNA-dependent DNA cleavage activity of yeast Rnt1p. J Mol Biol 338: 401–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie M, Abou Elela S 2008. Yeast ribonuclease III uses a network of multiple hydrogen bonds for RNA binding and cleavage. Biochemistry (Mosc) 47: 8514–8526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Radmark O, Kim S, et al. 2003. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature 425: 415–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HL, Chelladurai BS, Zhang K, Nicholson AW 1993. Ribonuclease III cleavage of a bacteriophage T7 processing signal. Divalent cation specificity, and specific anion effects. Nucleic Acids Res 21: 1919–1925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Pallan PS, Maier MA, Rajeev KG, Mathieu SL, Kreutz C, Fan Y, Sanghvi J, Micura R, Rozners E, et al. 2007. Crystal structure, stability and in vitro RNAi activity of oligoribonucleotides containing the ribo-difluorotoluyl nucleotide: insights into substrate requirements by the human RISC Ago2 enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 6424–6438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma JB, Ye K, Patel DJ 2004. Structural basis for overhang-specific small interfering RNA recognition by the PAZ domain. Nature 429: 318–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E, MacRae IJ, Kirsch JF, Doudna JA 2008. Autoinhibition of human dicer by its internal helicase domain. J Mol Biol 380: 237–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae IJ, Doudna JA 2007. An unusual case of pseudo-merohedral twinning in orthorhombic crystals of Dicer. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 63: 993–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacRae IJ, Zhou K, Li F, Repic A, Brooks AN, Cande WZ, Adams PD, Doudna JA 2006. Structural basis for double-stranded RNA processing by Dicer. Science 311: 195–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng W, Nicholson AW 2008. Heterodimer-based analysis of subunit and domain contributions to double-stranded RNA processing by Escherichia coli RNase III in vitro. Biochem J 410: 39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel R, Ares M Jr 2000. Substrate recognition by a eukaryotic RNase III: The double-stranded RNA-binding domain of Rnt1p selectively binds RNA containing a 5′-AGNN-3′ tetraloop. RNA 6: 1142–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima A, Takaku H, Shibata HS, Negishi Y, Takagi M, Tamura M, Nashimoto M 2007. Gene silencing by the tRNA maturase tRNase ZL under the direction of small-guide RNA. Gene Ther 14: 78–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AW 1992. Accurate enzymatic cleavage in vitro of a 2′-deoxyribose-substituted ribonuclease III processing signal. Biochim Biophys Acta 1129: 318–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AW 1999. Function, mechanism and regulation of bacterial ribonucleases. FEMS Microbiol Rev 23: 371–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AW, Niebling KR, McOsker PL, Robertson HD 1988. Accurate in vitro cleavage by RNase III of phosphorothioate-substituted RNA processing signals in bacteriophage T7 early mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res 16: 1577–1591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provost P, Dishart D, Doucet J, Frendewey D, Samuelsson B, Radmark O 2002. Ribonuclease activity and RNA binding of recombinant human Dicer. EMBO J 21: 5864–5874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson HD, Dunn JJ 1975. Ribonucleic acid processing activity of Escherichia coli ribonuclease III. J Biol Chem 250: 3050–3056 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby JG, Jan CH, Bartel DP 2007. Intronic microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature 448: 83–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sashital DG, Doudna JA 2008. Structural insights into RNA interference. Curr Opin Struct Biol 20: 90–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweisguth DC, Chelladurai BS, Nicholson AW, Moore PB 1994. Structural characterization of a ribonuclease III processing signal. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svoboda P 2004. Long dsRNA and silent genes strike back: RNAi in mouse oocytes and early embryos. Cytogenet Genome Res 105: 422–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Mil A, Doevendans PA, Sluijter JP 2009. The potential of modulating small RNA activity in vivo. Mini Rev Med Chem 9: 235–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Juranek S, Li H, Sheng G, Tuschl T, Patel DJ 2008a. Structure of an argonaute silencing complex with a seed-containing guide DNA and target RNA duplex. Nature 456: 921–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sheng G, Juranek S, Tuschl T, Patel DJ 2008b. Structure of the guide-strand-containing argonaute silencing complex. Nature 456: 209–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Juranek S, Li H, Sheng G, Wardle GS, Tuschl T, Patel DJ 2009. Nucleation, propagation and cleavage of target RNAs in Ago silencing complexes. Nature 461: 754–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Henras A, Chanfreau G, Feigon J 2004. Structural basis for recognition of the AGNN tetraloop RNA fold by the double-stranded RNA-binding domain of Rnt1p RNase III. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 8307–8312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazbeck DR, Min KL, Damha MJ 2002. Molecular requirements for degradation of a modified sense RNA strand by Escherichia coli ribonuclease H1. Nucleic Acids Res 30: 3015–3025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YR, Pei Y, Chen HY, Tuschl T, Patel DJ 2006. A potential protein–RNA recognition event along the RISC-loading pathway from the structure of A. aeolicus Argonaute with externally bound siRNA. Structure 14: 1557–1565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Kolb FA, Jaskiewicz L, Westhof E, Filipowicz W 2004. Single processing center models for human Dicer and bacterial RNase III. Cell 118: 57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]