Over the past decades, there have been significant efforts devoted to explore the use of nanoparticles in the fields of biology and medicine. Several different types of nanoparticles have successfully made their ways into pre-clinical studies in animals, clinic trials in patients or even successful commercial products used in routine clinical practice.[1] For example, gold nanoshells,[2] quantum dots [3, 4] and super-paramagnetic nanoparticles[5] which carry target-specific ligands have been employed in in vivo cancer imaging; drug molecules can be packaged into polymer-based nanoparticles and/or liposomes[6, 7] to achieve controlled released at disease sites;[8, 9] positively charged nanoparticles can serve as a non-viral delivery system for both in vitro and in vivo genetic manipulation and programming.[1, 10, 11] However, there remains an imperious desire for developing novel synthetic approaches in order to produce new-generation nanoparticles which have (i) controllable sizes and morphologies, (ii) low toxicity, compatible immunogenicity and in vivo degradability, and (iii) proper surface charges and chemistry for improved physiological stability and longer circulation time. Moreover, multiple functions[12] – for example, reporter systems for real-time monitoring with imaging technologies (i.e., optical imaging, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET)), targeting ligands for disease-specific delivery, and controllable mechanism for packaging and releasing of drugs and genes – will be conferred to individual nanoparticles for conducting multiple applications in parallel.

Different from the conventional chemical synthesis capable of forming/breaking covalent bonds, supramolecular chemistry, combining two basic concepts – self assembly and molecular recognition – offers a powerful and convenient tool for preparation of nanostructured materials from molecular building blocks.[13–18] The fact is that the concept of self assembly has been extensively used to prepare organic nanoparticles. For instance, liposomes and nano-scaled vesicles,[7] which were prepared through self-assembly of phospholipids, can serve as powerful nano-carriers for drug and gene delivery; self-assembled amphiphilic copolymers building blocks spontaneously forms nanoparticles, which can be utilized for drug delivery and molecular imaging.[19–22] However, it is apparent that the concept of “molecular recognition” seems to be an underappreciated factor, which could enable much sophisticated synthetic approaches,[23] allowing precise control of the properties of the resulting nanoparticles. β-Cyclodextrin (CD) is one of the most commonly used supramolecular building blocks for diversity of biomedical applications.[24, 25] CD-containing cationic polymers have been employed as vectors for highly efficient delivery of siRNA. Through the CD/adamantane (Ad) recognition, Ad-functionalized PEG chains were grafted onto the nanoparticles to enable long-term systemic circulation in vivo.[26]

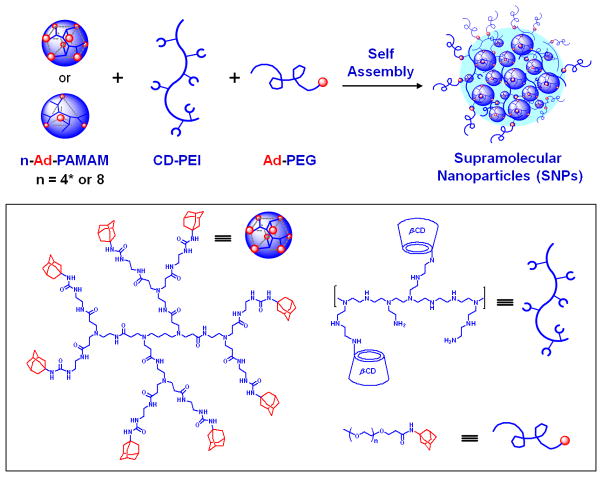

Herein, we report a convenient, flexible and modular synthetic approach (Figure 1) for preparation of size-controllable supramolecular nanoparticles (SNPs). The CD/Ad recognition was employed to achieve self assembly of SNPs from three different molecular building blocks – namely (i) Ad-grafted 1st-generation polyamidoamine dendrimer, n-Ad-PAMAM, (ii) β-CD-grafted branched polyethylenimine (MW=10 kD), CD-PEI, and (iii) Ad-functionalized PEG compound (MW=5 kD), Ad-PEG. Similar to a previously reported “bricks and mortar” strategy[23] to construct cross-linked network.[27] The uniqueness of our design is the use of a capping/solvation group, Ad-PEG, which, on one hand, competes with the dendrimer block, n-Ad-PAMAM to constrain the continuous propagation of the cross-linked network, and on the other hand, confers water-solubility to the SNPs. By tuning mixing ratios among the three molecular building blocks in PBS aqueous solution (pH = 7.2, containing 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 155 mM NaCl and 2.7 mM Na2HPO4), the equilibrium between the propagation/aggregation and capping/solvation of the cross-linked network fragments can be altered, allowing arbitrary control of the sizes of the water-soluble SNPs. In contrast to the production of polymer-based nanoparticles, [19, 20, 22] where significant synthetic endeavors were required to prepare specific types of polymeric building blocks in order to achieve desired size controllability, our three-component supramolecular approach offers synthetic convenience, flexibility and modularity to alter sizes and surface chemistry of the SNPs. Based on such a supramolecular approach, we were able to obtain a collection of SNPs with controllable sizes ranging from 30 to 450 nm. Further studies were carried out to unveil unique properties of these SNPs, including (i) their stability at different temperatures and pH values, as well as in physiological ionic strength media, (ii) the competitive disassembly in the presence of Ad molecules, and (iii) the reversible size controllability via in situ alteration of mixing ratios of the molecular building blocks. Finally, whole-body biodistribution and lymph node drainage studies of both of the 30- and 100-nm 64Cu-labeled SNPs in mice were carried out using microPET/CT imaging. The results revealed that the sizes of SNPs are crucial factors, which affect the respective in vivo properties of the SNPs.

Figure 1.

Graphical representations of a convenient, flexible and modular synthetic approach for preparation of size-controllable supramolecular nanoparticles (SNPs). A molecular recognition system based on adamantane (Ad) and β-cyclodextrin (CD) was employed to assemble three molecular building blocks (i) n-Ad-PAMAM, (n = 4* or 8) (ii) CD-PEI, and (iii) Ad-PEG.

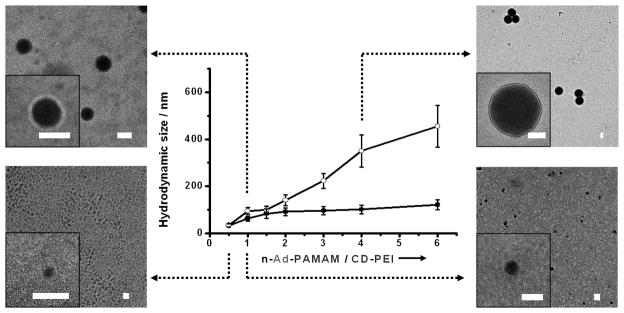

The three molecular building blocks – n-Ad-PAMAM, CD-PEI and Ad-PEG, were prepared and characterized (Supporting Information, Section 1.2). In the polymer building block CD-PEI, there are ca. 7 to 8 CD recognition units grafted on a branched PEI backbone according to its 1H NMR spectrum. It is well known that the CD modification increases biocompatibility and reduces toxicity of the PEI compounds.[28] In our experiments, two different dendrimer building blocks, i.e., 8-Ad-PAMAM with eight substituted Ad motifs and 4*-Ad-PAMAM[29] with four Ad motifs (in average, based on its 1H NMR spectrum), were tested in parallel. To examine how the mixing ratios between Ad-PAMAM and CD-PEI affect the sizes of the resulting SNPs, we utilized dynamic light scattering (DLS, N4 plus, USA) measurements to analyze the freshly prepared SNPs. To ensure sufficient supply of the capping/solvation group, an excess amount of Ad-PEG were added in to each mixture. In the absence of Ad-PEG, direct mixing of n-Ad-PAMAM and CD-PEI resulted in aggregation and precipitation. The octa-substituted dendrimer 8-Ad-PAMAM was first tested. In this case, CD-PEI (168 μM) in PBS buffer was slowly added into the mixtures containing Ad-PEG (840 μM) and variable amount (84 to 672 μM) of 8-Ad-PAMAM. As shown in Figure 2a, we were able to obtain a collection of water-soluble SNPs with variable sizes ranging between 30 and 450 nm. Meanwhile, the surface charge densities of SNPs (with diameters range from 30 to 450 nm) were determined by zeta potential (ζ) measurements in PBS buffer solution (Zetasizer Nano, Malvern Instruments Ltd), suggesting that the SNPs carry zeta potentials in a range of 16.8 ± 1.2 to 28.5 ± 1.1 mV (see Figure S1 in Supporting Information,). To test how the number of the Ad-substitution groups in a dendrimer core affects the sizes of the respective SNPs, the tetra-substituted dendrimer 4*-Ad-PAMAM was also examined. We were able to obtain SNPs with relative smaller sizes (30 – 120 nm) under similar self-assembly conditions. The morphology and size of SNPs were also examined by using transmission electron microscope (TEM, Philips CM-120). As shown in Figures 2b-e, TEM images suggest that the SNPs exhibit the spherical shapes and narrow size distributions (see Figure S2 in Supporting Information), which are consistent to those observed by DLS.

Figure 2.

a) Titration plots summarize the relationship between SNP sizes and mixing ratios of the two molecular building blocks (n-Ad-PAMAM/CD-PEI). Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was employed to measure SNP sizes. Hollow circles: the titration plot observed for an octa-substituted dendrimer building block 8-Ad-PAMAM; Solid circles: the titration plot observed for a tetra-substituted dendrimer building block 4*-Ad-PAMAM. The standard deviation of each data point was contained from, at least, three repeats. TEM images of the resulting SNPs with different sizes of b) 32 ± 7 nm from 8-Ad-PAMAM, c) 61 ± 17 nm from 4*-Ad-PAMAM, d) 104 ± 16 nm from 8-Ad-PAMAM and e) 340 ± 46 nm from 8-Ad-PAMAM. Scale bars: 100 nm.

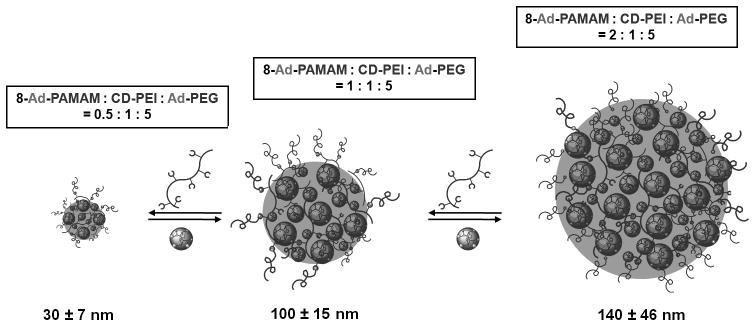

The use of supramolecular approach conferred dynamic characteristics to the self-assembled SNPs. To understand the dynamic stability of the SNPs, we employed real-time DLS measurements to monitor the size variation of the 30- and 100-nm SNPs (composed of 8-Ad-PAMAM-based dendrimer) at different temperatures and pH values, as well as in physiological ionic strength media. First, the variable-temperature DLS measurements indicate that the SNPs are stable at wide range of temperature (7 to 50°C). (see Figure S4 in Supporting Information) Second, we observed negligible size variation of the SNPs against the changes of pH values (from pH 3.8 to 8.3) and physiological ionic strength. (see Figures S3 and S5 in Supporting Information) We note that the stability of these SNPs can be attributed to the multivalent CD/Ad recognition, which holds individual molecular building blocks into each SNP. Two sets of experiments were carried out to examine the dynamic characteristics (i.e., competitive disassembly and reversible size controllability) of these SNPs, which further validate the molecular mechanism of this supramolecular approach. First, we introduced 100 eq of a competitive reagent (i.e., 1-adamantamine hydrochloride) into a solution containing either 30-or 100-nm SNPs. After 10-min sonication, disassembly of SNPs was observed by DLS as a result of competition inclusion of the free 1-adamantamine hydrochloride into CD-PEI. As a control, without the addition of 1-adamantamine hydrochloride, sonication alone could not disassemble the SNPs (see Figure S6 in Supporting Information). Second, starting from 100-nm SNPs (8-Ad-PAMAM/CD-PEI = 1:1, mol/mol), we were able to reduce the size of SNPs to 30 nm by adding the polymer component CD-PEI in situ (8-Ad-PAMAM/CD-PEI = 1:2, mol/mol), or increase the size of SNPs to 140 nm by adding the dendrimer component 8-Ad-PAMAM in situ (8-Ad-PAMAM/CD-PEI = 2:1, mol/mol). In these studies, 10-min sonication was employed to facilitate the conversion among the three sizes of SNPs.

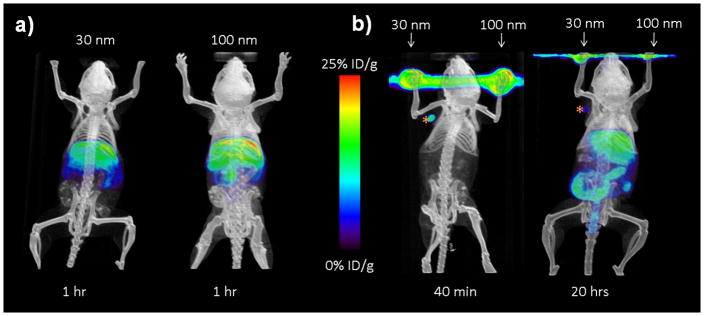

We characterized the in vivo biodistribution (see Figure 4a and Figure S7 in Supporting Information) of both of the 30- and 100-nm 64Cu-labeled SNPs (composed of 8-Ad-PAMAM-based dendrimer, see Supporting Information for SNPs labeling protocols) by systemically injecting the SNPs into mice via the tail veins (see Figure S8d in Supporting Information). MicroPET/CT studies suggested that the biodistribution patterns of the 30- and 100-nm SNPs were quite similar (see Figure S8a and b in Supporting Information). In both cases, rapid blood clearance through liver accumulation (30–50% ID/g of the SNPs accumulated in the liver within 5 min after injection) was observed, and there was less accumulation in the kidneys (16–20% ID/g) and lungs (8–12% ID/g). A nonlinear two-phase decay fit of the SNPs plasma concentrations yielded initial elimination half-lives of 0.87 min and 1.1 min for the 30- and 100-nm SNPs, respectively. The terminal elimination half-lives were also quite different (30-nm SNPs was 68 min, and 100-nm SNPs was 108 min). Together, the results indicated that the in vivo clearance of the 30-nm SNPs is faster than that of the 100-nm SNPs.

Figure 4.

MicroPET/CT studies of both 30- and 100-nm 64Cu-labeled SNPs at various time points after injections into mice. a) In vivo biodistribution studies of the SNPs by systemically injecting the SNPs into mice via the tail veins. Left panel: 30-nm SNPs; right panel: 100-nm SNPs. b) Lymph node trafficking studies of SNPs via front footpad injections. The 30- and 100-nm SNPs were injected respectively on different sides of footpads of a mouse. MicroPET/CT was carried out for 40 min (left panel) immediately after injection and also at 20 h post injection (right panel).

To explore the use of the SNPs for immune modulation, we investigated the lymph node trafficking of both 30-and 100-nm 64Cu-labeled SNPs via front footpad injection (see Figure S8d in Supporting Information). The path of lymph drainage from footpad injections is well known, and hence this is a common method for delivery of immunological agents.[30] We injected the 30- and the 100-nm SNPs on different sides of footpads of a mouse, and microPET/CT imaging was carried out for 40 min (Figure 4b, left panel) immediately after injection and at 20 h post injection (Figure 4b, right panel). We observed that the 30-nm SNPs drained to the local auxiliary lymph node and peaked at 5 min post injection with 58.6±15.6% ID/g of signal accumulation (see Figure S8c in Supporting Information). This signal decreased to 26.6±5.8% ID/g at 40 min post injection, and further reduced to 7.0±2.2% ID/g by 20 h post injection. No significant accumulation was detected in the lymph nodes on the same side that the 100-nm SNPs were injected. Other than the footpad injection site and the lymph node in which the 30-nm SNPs were drained, the SNPs did not distribute to other regions in vivo by 1 h after injection. The results revealed that the sizes of SNPs are critical factors for their lymph node trafficking.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a convenient, flexible and modular synthetic approach for preparation of size-controllable SNPs. PET imaging studies were carried out by injecting 64Cu-labeled SNPs with different sizes into mice. Both whole-body biodistribution and lymph node drainage studies revealed that the sizes of SNPs affect their in vivo characteristics. Besides the imaging studies shown in this work, we are currently exploring the use of the size-controllable SPNs for other biomedical applications. Much extensive and in-depth study will reveal the potentials of these SNPs.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Schematic representation illustrating the reversible size controllability of SNPs

Footnotes

H. R.T. and C.G.R. acknowledges support from the NIH-NCI NanoSystems Biology Cancer Center (U54CA119347).

References

- 1.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:771. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loo C, Lin A, Hirsch L, Lee MH, Barton J, Halas N, West J, Drezek R. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2004;3:33. doi: 10.1177/153303460400300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nie SM, Xing Y, Kim GJ, Simons JW. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.152025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jun YW, Lee JH, Cheon J. Angew Chem. 2008;120:5200. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:5122. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heath JR, Davis ME. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.061506.185523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torchilin VP. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:145. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Napier ME, Desimone JM. Poly Rev. 2007;47:321. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gratton SE, Williams SS, Napier ME, Pohlhaus PD, Zhou Z, Wiles KB, Maynor BW, Shen C, Olafsen T, Samulski ET, Desimone JM. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1685. doi: 10.1021/ar8000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green JJ, Langer R, Anderson DG. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:749. doi: 10.1021/ar7002336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pack DW, Hoffman AS, Pun S, Stayton PS. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:581. doi: 10.1038/nrd1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai WB, Chen XY. Small. 2007;3:1840. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer CD, Joiner CS, Stoddart JF. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1705. doi: 10.1039/b513441m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hwang I, Jeon WS, Kim HJ, Kim D, Kim H, Selvapalam N, Fujita N, Shinkai S, Kim K. Angew Chem. 2007;119:214. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:210. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ludden MJW, Reinhoudt DN, Huskens J. Chem Soc Rev. 2006;35:1122. doi: 10.1039/b600093m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SY, Lytton-Jean AKR, Lee B, Weigand S, Schatz GC, Mirkin CA. Nature. 2008;451:553. doi: 10.1038/nature06508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stoddart JF, Tseng HR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052708999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Wang H, Liang P, Zhang HY. Angew Chem. 2004;116:2744. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:2690. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun G, Xu J, Hagooly A, Rossin R, Li Z, Moore DA, Hawker CJ, Welch MJ, Wooley KL. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3157. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira L, Karp JM, Nobre L, Langer R. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:136. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bull SR, Guler MO, Bras RE, Meade TJ, Stupp SI. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1. doi: 10.1021/nl0484898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertin PA, Gibbs JM, Shen CKF, Thaxton CS, Russin WA, Mirkin CA, Nguyen ST. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4168. doi: 10.1021/ja056378k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boal AK, Ilhan F, DeRouchey JE, Thurn-Albrecht T, Russell TP, Rotello VM. Nature. 2000;404:746. doi: 10.1038/35008037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wenz G, Han BH, Muller A. Chem Rev. 2006;106:782. doi: 10.1021/cr970027+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Loh XJ. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:1000. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartlett DW, Su H, Hildebrandt IJ, Weber WA, Davis ME. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707461104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellocq NC, Kang DW, Wang XH, Jensen GS, Pun SH, Schluep T, Zepeda ML, Davis ME. Bioconjugate Chem. 2004;15:1201. doi: 10.1021/bc0498119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis ME, Brewster ME. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:1023. doi: 10.1038/nrd1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.According to MS analysis, 4*-Ad-PAMAM is composed of six different Ad-substituted PAMAMs, including 2-Ad-PAMAM, 3-Ad-PAMAM, 4-Ad-PAMAM, 5-Ad-PAMAM, 6-Ad-PAMAM and 7-Ad-PAMAM. See detail MS data in Supporting Information.

- 30.Peek LJ, Middaugh CR, Berkland C. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:915. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.