When we throw out our trash it is burned in an incinerator or buried in a landfill. If we burn our trash, it pollutes the air. If we bury it, it fills up our landfills and gets out of hand. But if we recycle things, it will not pollute anything and we can use it over again. By recycling we also save money.

Our county has a recycling program. Every Friday, you have a chance to put out your trash for recycling and the garbage men will pick it up. We can recycle milk jugs, aluminum cans, plastic soda bottles, and newspaper.

Unfortunately, not everybody takes part in this program. Some people don't recycle at all, and others don't put out as much as they could.

Purpose

My purpose was to try and get more people to recycle. I gave them notes that told them how well their street was doing each week. I also promised that two gift certificates from the Bi-Lo grocery store would go to a homeless shelter if they increased their recycling.

Hypothesis

What I thought would happen was that on the street where I gave the notes more people would recycle. I didn't think there would be any change on the other street where I didn't give notes.

Method

Variables

The variable I measured was how many houses had a recycling bin out on Friday morning. At first I was going to measure how much trash was in the bin, but I thought people wouldn't like me looking through their trash.

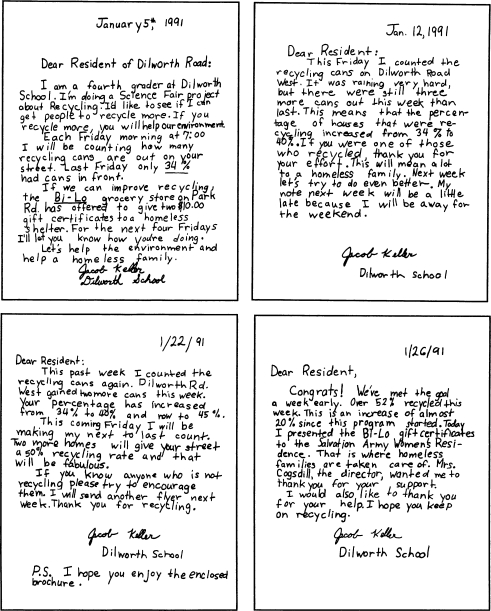

The variable I changed was the notes I delivered on one street. I put these notes on the door step. The notes said how many people had recycled that week. Examples of the different notes I delivered each week are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The notes I delivered to the homes on Dilworth Road West to get more people to recycle. I gave out the first note on Saturday, January 5, after taking my first measurements on Friday, January 4. The second, third, and fourth notes were delivered during the next 3 weeks.

Another variable was the Bi-Lo gift certificate. The manager of the Bi-Lo grocery store on Park Road gave me two $10.00 gift certificates for the project. I told the people that these would go to a homeless shelter if they increased their recycling.

Results

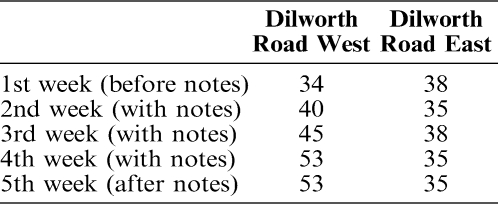

There were 44 total homes on Dilworth Road West (where I gave notes) and 40 total homes on Dilworth Road East (where I didn't give notes). I figured out what percentage of the homes recycled on the two streets. Dilworth Road West, which got the notes, changed more than Dilworth Road East, which didn't get notes. When the experiment first started, the percentages were about the same. After I started giving notes, the percentages increased for Dilworth Road West. Even after I told the people on Dilworth Road West that the experiment was over, they still kept going strong. The percentages are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Percentage of Homes Recycling on Dilworth Road West (Notes) and Dilworth Road East (No Notes)

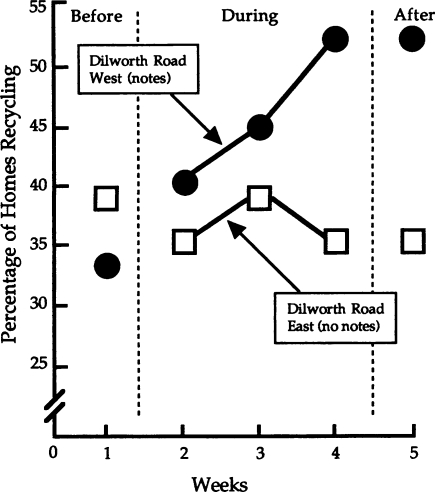

I have shown the same information in a graph (see Figure 2). This graph shows how much Dilworth Road West improved. The people on Dilworth Road East kept at about the same level. Dilworth Road East didn't know anything about this project.

Figure 2.

Percentage of homes on Dilworth Road West (notes) and Dilworth Road East (no notes) with materials for recycling on five consecutive Fridays.

Conclusions

This experiment has shown that it is possible to increase the number of people who recycle. With a little encouragement and showing them how well they are doing, people will be more likely to remember to recycle. Also, I think that people like to help other people. In this experiment they could provide a donation to a homeless shelter by recycling. They showed that they were willing to make an effort. My study also showed that even after the experiment was over, they still kept recycling at the same rate. Hopefully, they'll continue to recycle.

Note. Reprinted from Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 617–619, 1991, with permission from the Society for the Experimental Analysis of Behavior.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the people on Dilworth Road West for participating. I'd also like to thank Mr. Franklin, the manager of the Bi-Lo grocery store, who donated the two gift certificates; Connie Cogsdill, the Director of the Salvation Army Women's Residence, for her help; Scott Lipscomb and Nakia Lewis who helped me deliver the notes to the houses; Paula Hoffman, the Director of Education at the Mecklenburg County Recycling Center, who gave me a tour of the Center; Cindy Clemens, Resource Specialist, who sent me a lot of information and stickers; Ellen Silverman, PhD candidate at Virginia Tech, who put my paper on computer disc for the journal printers; Thomas Berry, PhD candidate at Virginia Tech, who helped me prepare Figure 2.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: On August 16, 1991, I received this research report from Fred S. Keller, grandfather of the author, when Thomas Berry and I were in the midst of finalizing the articles for this special issue on behavioral community intervention. The paper, handwritten by 10-year-old Jacob Keller, illustrated an inspirational example of “active caring” —the theme of my editorial for this issue. The paper was accepted without revision and printed here with minimal editing to reflect the sincerity and insight of this young behavioral community researcher. When actively caring, one can make a difference at any age.—E.S. Geller