Abstract

Soybean lipoxygenase-1 (SLO) catalyzes the oxidation of linoleic acid. The rate-limiting step in this transformation is the net abstraction of the pro-S hydrogen atom from the center of the 1,5-pentadienyl moiety in linoleic acid. The large deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIE) for this step appears in the first order rate constant (Dkcat = 81 ± 5 at T = 25 °C). Furthermore, the KIE and the rate for protium abstraction are weakly temperature dependent (EA,D − EA,H = 0.9 ± 0.2 kcal/mol and EA,H = 2.1 ± 0.2 kcal/mol, respectively). Mutations at a hydrophobic site about 13 Å from the active site Fe(III), Ile553, induce a marked temperature dependence that varies roughly in accordance with the degree to which the residue is changed in bulk from the wild type Ile. While the temperature dependence for these mutants varies from the wild type enzyme, the magnitude of the KIE at 25 °C is on the same order of magnitude. A hydrogen tunneling model [Kuznetsov, A.M., Ulstrup, J. Can. J. Chem. 77 (1999) 1085–1096] is utilized to model the KIE temperature profiles for the wild type SLO and each Ile553 mutant. Hydrogenic wavefunctions are modeled using harmonic oscillators and Morse oscillators in order to explore the effects of anharmonicity upon computed kinetic observables used to characterize this hydrogen transfer.

Keywords: Hydrogen transfer, Tunneling, Enzyme dynamics, Lipoxygenase, Morse potential, Kinetic isotope effect, Reorganization energy, Gating, Promoting vibration, Marcus theory

1. Introduction

1.1. Failures of tunnel corrections

Hydrogen transfer reactions [1] are perhaps the most fundamental chemical reactions. However, many challenges exist concerning a description of these reactions. First, the small mass of the hydrogen atom makes it difficult to accurately treat hydrogen transfer using techniques which have met with success in quantitatively describing reactions in which the movement of more massive nuclei predominate. Semiclassical transition state theory (TST) in its numerous incarnations [2–5] has proven immensely successful at reproducing or predicting quantitative experimental observables in a host of chemical transformations. In the case of proton, hydride, and hydrogen atom transfers, however, the traditional concept of a transition state loses importance. Because the nuclear wavefunctions for vibrations that consist primarily of hydrogen motion are more diffuse than wavefunctions for vibrations of larger reduced mass, reaction coordinates for hydrogen transfers have significant portions of their length that are appreciably permeable to hydrogen tunneling. This quantum reality is in direct contrast with the establishment of a dividing surface which relegates one part of the potential energy surface (PES) to reactants and the remaining portion to products under all variants of semiclassical TST. Because of this irresolvable difference between quantum reality and semiclassical TST, quantitative analyses of reactions where observables exhibit a definitive contribution from quantum effects have been treated using a correction factor. In Eq. (1), the rate corrected for tunneling, k, is simply the product of the quantum correction, Q, and the semiclassical transition state theory rate constant, ksc.

| (1) |

The most utilized quantum mechanical correction to TST was first put forth by Bell [6,7]. This treatment assumes a barrier of parabolic shape with a given energy of activation (see Eq. (2)). In Eq. (2), ut = hcν‡/kBT is the reduced imaginary frequency, and α = E/kBT is the reduced energy of activation; both values are unitless. Northrop has published a version of this correction which is free of typographical errors [8]. The negative curvature of the potential energy barrier at the saddle point can be supplied as a parameter to fit experimental data or originate from the computation of the negative force constant at the transition state using electronic structure calculations. The energy of activation can be provided in a similar fashion, either from empirical rate data or electronic structure calculations.

| (2) |

In general, the Bell correction overestimates tunneling amplitudes. This is because the parabolic barrier is, in the case of regularly shaped reaction coordinates, thinner than the barrier along the reaction coordinate. More recent methods of employing tunnel corrections to semiclassical TST utilize a Boltzmann-weighted JWKB integration of the imaginary action traversed under the potential surface [9,10]. While these calculations are ideally more realistic than the assumption of a barrier of given shape, they suffer from two inadequacies: (1) The computational difficulties inherent in defining a large enough portion of the PES with reliable levels of electronic structure theory lend uncertainty to the imaginary action relevant to the tunneling path. (2) The choice of the tunneling path is difficult, especially when it deviates strongly from both the minimum energy path (small curvature tunneling) and the least action path (extreme limit of large curvature tunneling) between reactant(s) and product(s).

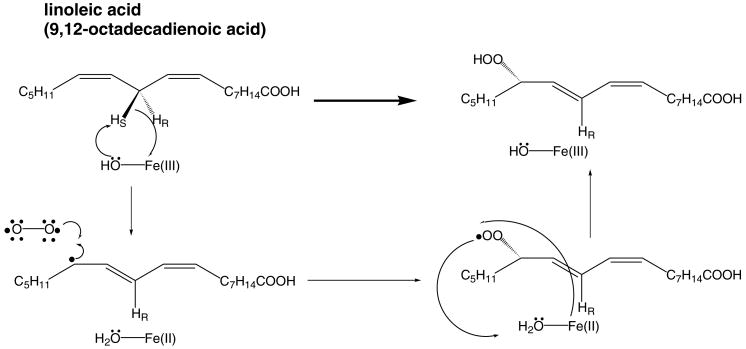

A good illustration of the difficulties outlined above is provided by a recent direct dynamics calculation of the oxidation of 1,4-pentadiene with a truncated model of SLO using the Fe(III) cofactor and its six ligands [11]. Whereas the experimental primary deuterium isotope effect for the hydrogen abstraction step in SLO (Fig. 1) is 81 [12], the value computed by direct dynamics at the PM3/d level of theory is 18.9. Although these calculations cannot quantitatively describe the hydrogen abstraction reaction catalyzed by SLO, there are some salient features of the PES that are captured in this particular calculation. First, the potential energy barrier is calculated to have a frequency of 2913i for the transfer of protium, which is one of the highest magnitude imaginary frequencies ever reported. Second, the reaction coordinate is shown to be composed primarily of hydrogen motion for a significant region in the vicinity of the transition state. These two characteristics suggest that a full tunneling model would be a more reasonable approach to modeling the hydrogen abstraction catalyzed by SLO, since hydrogen motion is, for all practical purposes, uncoupled from heavy atom motion for a significant part of the reaction.

Fig. 1.

Consensus mechanism for oxidation of linoleic acid catalyzed by SLO and its mutants. The first step in the mechanism, the abstraction of the 11-pro-S hydrogen on linoleic acid is the rate-limiting step, and is the focus of this article. The five amino acid ligands on the Fe(III) cofactor are omitted for clarity.

The failure of TST to reliably reproduce large KIEs in systems reacting at room temperature stems from the problem of determining the most probable tunneling path. Small curvature tunneling corrections fail to reproduce large KIEs because large KIEs are usually an indication that the tunneling path deviates significantly from the minimum energy path. Least action tunneling corrections are at the other extreme and are most germane to reactions carried out at low temperatures [13,14].

1.2. The physical meaning of large KIEs

While many features of TST with tunnel corrections may not be desirable when trying to model a system with an extremely large KIE, one feature of TST is superior in its descriptive power. The minimum energy path of a generic reaction is, by its nature, multidimensional, so the tunneling path which is derived from the minimum energy path in most treatments is inherently multidimensional. This fact forms the logical basis for the statement that heavy atom motion is always coupled, to some degree, to hydrogen motion. The magnitude of this coupling determines the adiabaticity of a given hydrogen transfer. If heavy atom motion closely tracks hydrogen transfer, then they move on the same time scale, and the transfer can be regarded as highly adiabatic. In contrast, if there exists a substantial part of the reaction coordinate that is described largely in terms of hydrogen motion, then the reaction can be regarded as being largely diabatic [15].

Hydrogen tunneling models that have been applied to modeling experimental data thus far focus on parameterizing most or all heavy atom motion, while the hydrogen transfer coordinate is treated as a special coordinate [15–28]. A primary detraction regarding these models is that the role of heavy atom motion is included in a semi-empirical sense. However, hydrogenic motion is treated explicitly and quantum mechanically. This lends utility in that fundamental observables regarding hydrogen transfer can be reproduced, i.e. the primary kinetic isotope effect and its dependence on temperature. While the quantitative assessment of some of the parameters in these models may amount to curve fitting in real cases, trends reproduced by these equations lend themselves to physical interpretation of the tunneling process itself.

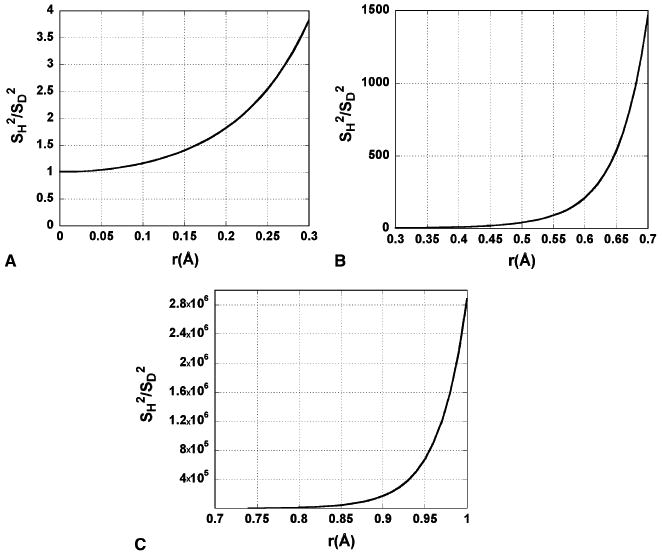

The construction of the hydrogen transfer model used in the current study relies upon the assumptions that the reaction can be treated as electronically diabatic and that the transfer of the hydrogen nucleus can be described diabatically. Importantly, according to Eqs. (30) and (31) of [23], the KIE is not appreciably affected by the diabaticity of the electron transfer event when hydrogen atom transfer is broken up into electron transfer and proton transfer components. The primary KIE for the hydrogen abstraction step in the SLO-catalyzed oxidation of linoleic acid is among the largest reported. Large KIEs are indicative of transfer distances which are on the order of the de Broglie wavelength or longer [15,23,29,30]. Such a situation implies that the rate is governed by configurations in which the overlap between the hydrogen donor and acceptor hydrogenic wavefunctions is small. At these large distances, the ratio of the overlap for two C–H stretching vibrational wavefunctions to the overlap for two C–D stretching vibrational wavefunctions is much greater than at shorter distances (Fig. 2, Eq. (3)). In Eq. (3), the superscripts on the individual wavefunctions denote donor (D) and acceptor (A) hydrogenic wavefunctions, and the subscripts v and w refer to the vibrational level of the donor and acceptor wavefunctions considered, respectively. The subscript, ‘L’, specifies isotopologue. The minimal overlap between these nuclear wavefunctions allows one to comfortably choose a diabatic model regarding the proton transfer coordinate. In [36], the electronic coupling term was adjusted to obtain the correct rate for wild type SLO; however, this value is of little concern for the modeling presented herein, which is focused solely on the KIEs and their attendant properties.

Fig. 2.

Ratio of the squared magnitude of vibrational wavefunction overlap for the ground states (v = w = 0) of C–H and C–D stretch motions considered in the hydrogen transfer model used in this article as a function of separation of vibrational well minima. (A) The ratio mentioned above for a well separation from 0.0 to 0.3 Å. Such an arrangement would require strong coupling (adiabaticity) to be physically allowed. Such an arrangement might be feasible in a very strong hydrogen bond. (B) The squared overlap ratio for H and D-substituted vibrational wavefunctions for a well separation from 0.3 to 0.7 Å. The ratio in the squared overlap spans three orders of magnitude, and the origin of extreme KIEs begins to be visible around 0.6 Å. (C) The above ratio for a well separation from 0.7 to 1.0 Å. The ratios in this region figure strongly into the KIEs computed in the current study.

| (3) |

1.3. Choice of a full-tunneling model

Computations of Tresadern et al. [11], have suggested that, even along the minimum energy path computed for the hydrogen abstraction catalyzed by SLO, a significant portion of the reaction coordinate is dominated by the motion of the transferred hydrogen. This, coupled with the extremely large primary KIE observed for SLO in many different experiments [12,31–36], supports the use of a diabatic transfer model for the nuclear hydrogenic wavefunctions. Ideally, computations used to quantitatively model KIEs should have a significant parameter set that can be directly compared to experimental measurements. The approach developed by Kuznetsov and Ulstrup [23,37] and modified by Knapp et al. [36] suits these purposes. This model allows for the inclusion of excited state vibrational wavefunctions in the hydrogenic coordinate for the hydrogen donor and acceptor. In Eq. (4a), the first summation (over v) is the sum over hydrogen donor vibrational states; whereas, the summation over w refers to acceptor hydrogenic vibrational states. Eq. (4b) is simply the normalization for the probability of occupation of donor hydrogenic vibrational states, or the partition function for this vibration. Eq. (4c) is composed of the nonadiabatic electronic coupling term, |Vel|2, a Levich–Dogonadze–Marcus-like expression [38,39] for the linear response of the reacting donor/acceptor pair to fluctuations in the solvent, Eq. (4d), and a term that computes the averaged square of overlap between donor and acceptor hydrogenic vibrational wavefunctions, Eq. (4e). A more detailed discussion of Eqs. (4e), (4f) and (4g) follows in Section 1.4.

| (4a) |

| (4b) |

| (4c) |

| (4d) |

| (4e) |

| (4f) |

| (4g) |

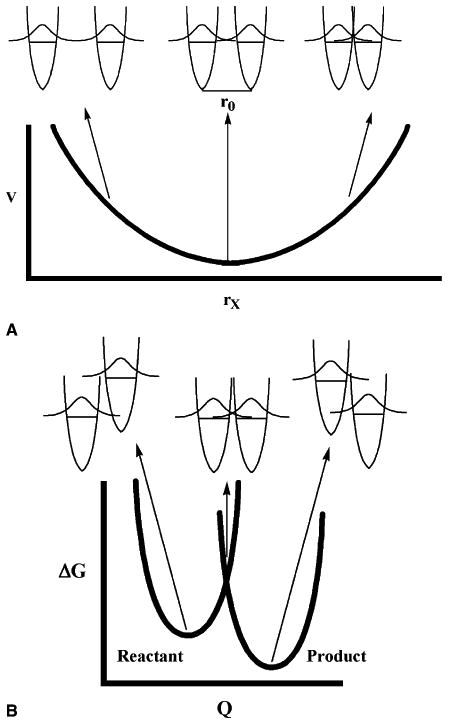

1.4. The impact of the protein: Distance sampling modes and environmental reorganization

Low temperature chemical reactions in solid matrices first prompted physicists to question the role of the reaction medium beyond its function as a thermal bath. As temperature decreases, reactions in solid matrices tend toward a limiting rate. At these temperatures, any significant thermally activated motions are ‘frozen out’. What first puzzled researchers was the fact that these limiting rates were orders of magnitude too high to be the result of unassisted tunneling from the ground state [13,14,40]. This observation, among others, precipitated the development of ‘promoting modes’ [15,28], that are present in the reaction medium and serve to modulate the separation between hydrogen donor and acceptor. These modes, which have also been referred to as ‘gating’ modes [36], have been applied to enzyme-catalyzed reactions [23,41–46], and in particular, to the hydrogen atom transfer catalyzed by SLO [23,36,45,46]. Gating modes are distinct from the reorganization energy, λ, in the Levich–Dogonadze–Marcus theory of tunneling (Fig. 3B), and can only contribute in an accelerative manner to the rate. At this juncture, we wish to clarify our view of the physical origin of gating modes, which represent distance sampling trajectories that take place within a protein that is in equilibrium with the thermal bath (solvent). These motions are likely to be fast (ns to ps) and, as a consequence, fairly local. Although we may refer to a gating mode (singular), the actual motion is expected to represent an average property of multiple excursions that affect the distance between the donor and acceptor atoms.

Fig. 3.

(A) Promoting mode vibrations serve to modulate the distance between the hydrogenic vibrational wavefunctions between the hydrogen donor and acceptor. Because this mode has no effect on the relative energies of the hydrogenic wavefunctions, it does not contribute to reorganization energy. (B) Antisymmetrically-coupled coordinates, collectively called Q here, serve to modulate the relative energies of the hydrogenic wavefunctions of the hydrogen donor and acceptor.

The gating mode used in this study follows the development in [23] and is a classical harmonic oscillator with energy, , where ΩX is the frequency of the gating mode in cm−1, and c is the speed of light. Accordingly, P(X) is merely a Boltzmann weighting for the classical gating vibration oscillator, Eq. (4f), where X is a reduced gating coordinate variable defined by Eq. (4g). The overlap shown in Eq. (4e) is a function of the vibrational states of the hydrogenic wavefunctions of the hydrogen donor and acceptor, v and w, respectively. The overlap is ultimately dependent upon the separation between the vibrational well minima, r = r0 − rX, where r0 is the well separation when the gating mode is at its lowest energy position. In other words, the motions of this mode are directly facilitating the hydrogen transfer coordinate. Given this definition of the gating mode coordinate, Eq. (4e) is the expectation of the overlap averaged over the possible values of rX.

The gating mode is in contrast to the Levich–Dogonadze–Marcus term that arises from thermally-averaged antisymmetric modes which serve to modulate the distance between the hydrogenic wavefunctions in energy space (Fig. 3B). These modes serve to bring about energetic coincidence of the donor and acceptor hydrogenic wavefunctions, which is necessary to achieve efficient overlap between the donor and acceptor wavefunctions. In the language of Cui and Karplus, these are referred to as ‘demoting modes’ [44]; however, this is only true in the case of a system that is symmetric in the absence of a solvent bath.

This investigation explores the effects of product excited states and the anharmonicity of the hydrogen donor and acceptor vibrational wavefunctions upon hydrogen atom transfer distance within the confines of the theory developed for non-adiabatic hydrogen atom transfer [23]. Recently determined data that are crucial to understanding the influence of gating modes in SLO are included in this analysis. The goal of modeling the experimental parameters for wild type and mutant enzyme forms is to understand the physical implications of the data, as reflected in the fixed and adjustable parameters of the model.

2. Computations

2.1. Treatment of the gating mode

The gating mode discussed herein impinges upon a reactive system which is embedded in a solvated protein matrix. This gating mode is likely to be the projection of the semi-random forces exerted upon the reacting system by the solvated protein. The phrase, ‘semi-random’ is meant to convey two ideas. First, a protein is an ordered entity that is composed of highly organized substructures. Second, it is conceivable that, because of its ordered nature, a protein could evolve to generate an ensemble of promoting modes that originate from a local flexibility within the protein structure. Whether this type of design finds its way into Nature's “toolkit” remains one of the important unanswered questions in the study of enzyme catalysis.

Because the reactive system is embedded in an extended molecular matrix, any gating vibration would inevitably be coupled to a large ensemble of oscillators within the protein matrix. This concept is analogous to the concept of phonons in solid matrices, which have been used to explain elevated rates in low temperature studies of chemical reactions which take place in solid matrices [15]. The analogy with phonons makes it physically appealing to use a classical oscillator to model the promoting mode [47].

Here, we use a gating mode of mass, 110 amu, and parameterize the frequency of this mode to best fit experimental data. The other adjustable parameter is the separation of donor and acceptor hydrogenic wells evaluated at the energy minimum of the gating mode coordinate; this value is denoted as r0. As stated before, the separation of the wells is given as a function of the gating mode coordinate, rX: r = r0 − rX. As pointed out by Hatcher et al. [45] the reduced mass of this mode has no real physical meaning until coupled with a frequency. Together, these values define the force constant of the vibration. The force constant of the vibration then defines the probability distribution of the gating mode and effectively defines the separation distance over which tunneling can occur.

2.2. Treatment of hydrogenic wavefunctions

One of the primary criticisms concerning a previous model of SLO catalyzed hydrogen transfer from this laboratory [36] was that the model led to a value for r0 of about 0.6 Å for wild type protein. This value, coupled with reasonable bond lengths [48] for C–H (1.09 Å) and O–H (0.96 Å) bonds, gives rise to a total C–O distance (2.65 Å) that is below that of the sum of van der Waals radii [49] (C: 1.70 Å, O: 1.52 Å) for these atoms. For this reason, it was decided to replace the former harmonic oscillator wavefunctions used to model the hydrogenic wavefunctions with Morse oscillators that incorporate the fundamental frequency of the harmonic oscillator and the dissociation energy of the C–H bond being cleaved [50]. We have used a classical dissociation energy, De, of 80.3 kcal/mol for loss of a hydrogen atom from the central methylene in a pentadienyl system (Fig. 1) and a fundamental C–H stretching frequency of 3000 cm−1. Morse oscillators are attractive for a couple of reasons. First, the Morse oscillator is the standard correction to the harmonic oscillator for the inclusion of dissociation energy [51]. Because they account for dissociation energy, they are more delocalized than harmonic oscillators in the direction of bond breakage. For this reason, transfer distances should be more realistic for Morse oscillators than harmonic oscillators. Second, the wavefunctions are known for the Morse oscillator, such that overlap integrals may be computed. The functional form for the oscillator wavefunctions used in the current study comes from [52] Eqs. (5a)–(5h). In Eqs. (5a)–(5h), ‘L’ denotes isotopic label; D/A denote donor/acceptor; μL is the reduced mass for the hydrogenic wavefunction with isotopic label, ‘L’; νL is the fundamental vibrational frequency for a harmonic oscillator with equal curvature at the minimum to the Morse oscillator; r is the separation distance of the minima of the donor and acceptor oscillators; q is the hydrogenic wavefunction coordinate. Subscripts and indices that indicate the vibrational state of the wavefunction are denoted by v for the donor wavefunction and w for the acceptor wavefunction. Associated Laguerre polynomials, , were computed using the Rodrigues expansion, Eq. (5i) [53].

| (5a) |

| (5b) |

| (5c) |

| (5d) |

| (5e) |

| (5f) |

| (5g) |

| (5h) |

| (5i) |

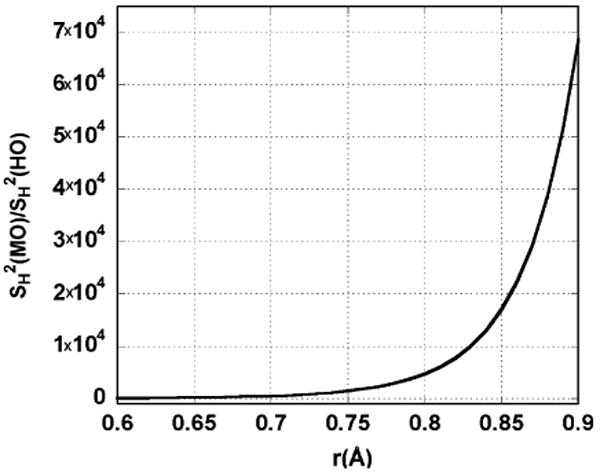

At hydrogenic wavefunction separations for which tunneling is important, the Morse oscillator shows much greater overlap than the overlap of two harmonic oscillator wavefunctions derived from a well of the same curvature at the minimum. This effect is visible in Fig. 4. Naturally, this effect manifests itself in longer transfer distances. For the purpose of clarity, it should be stated that r0 is not indicative of the separation of the donor/acceptor vibrational wells that gives rise to the maximal tunneling rate. The well separation that yields the maximal tunneling rate, referred to as r*, is a balance between the probability distribution for the position of the promoting mode coordinate and the overlap, which is parametrically dependent upon rX. It is r* that is affected in going from harmonic oscillators to Morse oscillators.

Fig. 4.

Ratio of squared overlap of Morse oscillator to harmonic oscillator as a function of separation of hydrogen donor and acceptor. This figure was computed from ground state wavefunctions (v = w = 0). Wavefunctions computed for the Morse oscillator have parameters chosen from empirically derived dissociation energy for the hydrogen abstraction catalyzed by SLO and the fundamental vibrational frequency of the harmonic oscillator for a typical C–H stretch (νH = 3000 cm−1). This figure illustrates that Morse wavefunctions have significantly better overlap than harmonic oscillators in the hydrogen transfer distances of interest.

2.3. Computational details

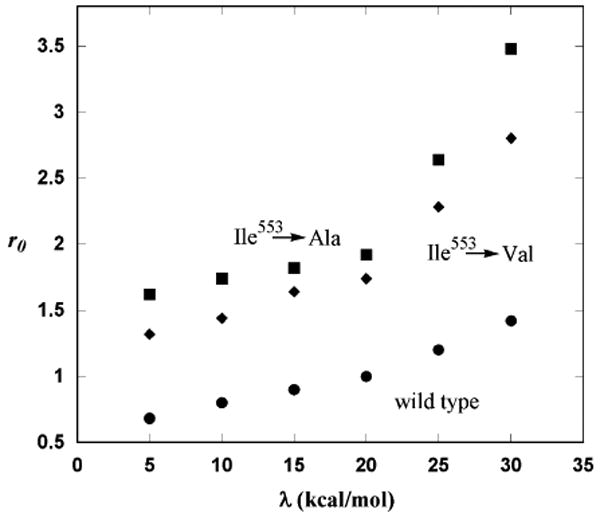

As discussed earlier, the parameter space explored in this study is the frequency of the promoting mode, ΩX, and the separation of donor and acceptor well minima at rX = 0. ΩX was varied from 10 to 400 cm−1. Given an oscillator mass of 110 amu, this corresponds to covering a range in force constant from 0.65 to 1038 J m−2. This range is likely to cover all physically relevant values, since the force constant for a typical C–H stretch with μH = 0.923 amu and νH = 3000 cm−1 is 490 J m−2. The reduced mass for the C–D stretch is μD = 1.71 amu. The separation of donor and acceptor well minima at rX = 0, which will henceforth be referred to as r0, was allowed to vary from 0.5 to 4.0 Å. A temperature range of 0–55 °C, germane to KIE data collected for wild type recombinant SLO and its Ile553 → Val, Ile553 → Ala, and Ile553 → Gly mutants, was explored in order to fit Arrhenius parameters from the temperature dependence of the KIE. The KIE was computed as a ratio of Eq. (4a) for the H isotopologue to that for the D isotopologue. The resulting KIEs were then fitted to the Arrhenius equation to compute ΔEA = EA,D − EA,H and AH/AD. These two parameters and the magnitude of the KIE at 30 °C were used to find the value of r0 and ΩX that best reproduced the experimental data. A scoring function, Eq. (6) was implemented that weighed these three parameters according to the relative error associated with each. This score was then minimized in a global search within the parameter space.

| (6) |

Parameters for the Marcus–Levich–Dogonadze term were taken from Knapp et al.: λ = 19.5 kcal/mol and ΔG0 = −6.0 kcal/mol. The vibrational energy in this term (Eq. (4d)) is simply computed from eigenvalue expressions for the Morse oscillator [52] or harmonic oscillator depending upon the type of hydrogenic wavefunctions employed. The electronic coupling was assumed to be isotope and distance independent, and, as such, was unnecessary for the computation of the KIE. The donor vibrational wavefunction is a C–H stretch; whereas, the acceptor vibrational wavefunction is an O–H stretch. Because the O–H oscillator is bound to an Fe(III) center, it was assumed that the normal frequency for an O–H vibrational stretch, 3500 cm−1, would be attenuated significantly, such that both the donor and acceptor vibrational wavefunctions could be described by the frequency of 3000 cm−1 [54].

3. Results

3.1. Parametric fit of experimental data

Non-competitive measurements of the deuterium KIE on the phenomenological rate constant, kcat, were determined for recombinant wild type SLO and for the following Ile553 mutants: Ile553 → Val, Ile553 → Ala, and Ile553 → Gly. The details of these experiments are included in [55]. Table 1 lists the relevant empirical and computed kinetic parameters, along with the values of r0 and ΩX that best fit the data for the tunneling model used here. It should be noted that, while the KIE at 30 °C, ΔEA, and AH/AD are linearly dependent under the Arrhenius equation, the gating model used here does not predict a linear dependence of the natural logarithm of the KIE versus the inverse temperature (cf. [36]).

Table 1. Parametersa, r0 and ΩX, that best reproduce the empirically determined values, AH/AD, ΔEA and KIE, for recombinant wild type SLO and Ile553 mutants of SLO.

| r0 (Å) | ΩX (cm−1) | AH/AD | ΔEA (kcal/mol) | KIE (30 °C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt-SLO (Exp.) | 18 ± 5 | 0.9 ± 0.2d | 81 ± 5d | ||

| wt-SLO (HOb) | 0.75 | 262 | 20 | 0.8 | 84 |

| wt-SLO (MOc) | 1.02 | 167 | 20 | 0.9 | 84 |

| Ile553 → Val (Exp.) | 0.29 ± 0.21 | 3.4 ± 0.4e | 75 ± 6e | ||

| Ile553 → Val (HOb) | 1.48 | 68 | 0.21 | 3.5 | 75 |

| Ile553 → Val (MOc) | 1.98 | 48 | 0.23 | 3.4 | 76 |

| Ile553 → Ala (Exp.) | 0.12 0.06 | 4.0 ± 0.3d | 93 ± 4d | ||

| Ile553 → Ala (HOb) | 1.74 | 60 | 0.12 | 4.0 | 93 |

| Ile553 → Ala (MOc) | 2.34 | 42 | 0.11 | 4.0 | 93 |

| Ile553 → Gly (Exp.) | 0.027 ± 0.034 | 5.3 ± 0.7e | 170 ± 16e | ||

| Ile553 → Gly (HOb) | 2.87 | 43 | 0.023 | 5.3 | 169 |

| Ile553 → Gly (MOc) | 3.35 | 33 | 0.023 | 5.3 | 171 |

For these calculations, the force constants reflecting the C–H and O–H stretches of the reactant and product are held constant at 3000 cm−1. The values are assumed for ΔG0 (−6.0 kcal/mol) and λ (19 kcal/mol) are assumed to be invariant.

Computed values treating the hydrogenic wavefunctions as harmonic oscillators.

Computed values treating the hydrogenic wavefunctions as Morse oscillators.

Experimental values from [36].

Experimental values from [54].

Three notable observances can be gleaned from Table 1. First, r0 is significantly larger for the Morse oscillator model of hydrogenic wavefunctions in wild type SLO than that for the harmonic oscillator model. Second, gating mode frequencies are significantly reduced in the Morse oscillator model for all mutants and wt-SLO. Finally, within the range of adjustable parameters explored, the gating model is capable of reproducing experimental trends for both wild type SLO and mutants. At van der Waals separation for O and C, which is 3.22 Å, hydrogen transfer distance in wild type SLO would amount to 1.17 Å, accounting for standard C–H and O–H bond distances. The Morse oscillator model puts r0 at 1.02 Å in contrast to 0.75 Å for the harmonic oscillator model. The role of r0 in hydrogen transfer in mutant proteins will be discussed in Section 4.2. The value for wild type SLO is approaching what would be expected for van der Waals separation of the donor and acceptor atoms; however, this completely excludes the effects of attractive forces stronger than van der Waals forces. There is obviously some electronic coupling between the hydrogen donor (linoleic acid) and the hydrogen acceptor Fe(III)–OH, or the reaction would not occur. In a molecular orbital picture, pairwise electronic orbital interactions that result in a reaction contain less than the four electrons that would be present if both orbitals were completely filled [56]. Orbital interactions of this nature are attractive ones, so it stands to reason that, for a reacting system, the reaction partners could approach each other at less than van der Waals distance without immediately embarking on the reactive event. In other words, it is feasible that the ES complex in wild type SLO represents a local minimum on the free energy surface in which the reactive carbon of linoleic acid (C11) is less than 3.22 Å from the oxygen of the Fe(III)–OH cofactor. Heavy atom approach distances that are separated by less than van der Waals distance are not unreasonable, even in the absence of a traditional hydrogen bond (cf. Section 4.2).

3.2. Excited states extend r* and r0

The hydrogenic well separation, r*, that contributes most to the rate of hydrogen transfer is the result of a compromise between the squared overlap between the donor and acceptor hydrogenic wavefunctions equation (3) and the probability distribution for values of rX, Eq. (4f). Hydrogen transfer in this model is dominated by contributions from the ground vibrational state of the donor hydrogenic well; however, excited hydrogenic acceptor states are expected to play a dominant role in determining the rate of this exergonic hydrogen transfer where reorganization energy is minimized for hydrogen (or deuterium) transfer into states that are closest in energy to the reactant ground state. This effect is present when the hydrogenic wells are represented by harmonic oscillator wavefunctions but becomes more pronounced for Morse oscillators. This occurs for two reasons: First, the energy spacing between vibrational levels decreases with increasing quantum number (n) for Morse oscillators, while the vibrational energy spacing is constant for harmonic oscillators. Second, Morse oscillators become more diffuse at a faster rate than harmonic oscillators as the quantum number increases (Table 2). Table 2 clearly shows that, not only are Morse oscillator wavefunctions more diffuse than harmonic oscillator wavefunctions, but Morse oscillators are also asymmetrically offset from the potential energy minimum in such a way that overlap is enhanced. Both effects are enhanced as the quantum number increases. Obviously, r* will increase with the quantum number of the acceptor wavefunction.

Table 2. Expectation values for hydrogenic coordinate position (〈q〉), the square of this value (〈q2〉), and the dispersion of the wavefunction (〈q2〉 − 〈q〉2) as a function of quantum number for both the Morse oscillator and the harmonic oscillator.

| n | Harmonic oscillator | Morse oscillator | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 〈q〉 (Å)a | 〈q2〉 (Å2) | 〈q2〉 - 〈q〉2 (Å2) | 〈q〉 (Å) | 〈q2〉 (Å2) | 〈q2〉 - 〈q〉2 (Å2) | |

| 0 | 0.0 | 0.0061 | 0.0061 | 0.0195 | 0.0067 | 0.0063 |

| 1 | 0.0 | 0.0182 | 0.0182 | 0.0602 | 0.0230 | 0.0194 |

| 2 | 0.0 | 0.0304 | 0.0304 | 0.1039 | 0.0441 | 0.0334 |

| 3 | 0.0 | 0.0426 | 0.0426 | 0.1507 | 0.0711 | 0.0484 |

| 4 | 0.0 | 0.0547 | 0.0547 | 0.2013 | 0.1052 | 0.0647 |

| 5 | 0.0 | 0.0669 | 0.0669 | 0.2561 | 0.1479 | 0.0823 |

Both the asymmetry and the dispersion of the Morse oscillator allow for better overlap at larger separations of hydrogenic wells than harmonic oscillator wavefunctions.

〈q〉 is zero for any symmetric potential centered at the origin.

3.3. Differences in distance of most probable transfer

In terms of promoting hydrogen transfer, the function of the gating mode is to bring the separation of the hydrogen donor and acceptor wavefunctions from r0 to r*. Both the experimental data and the trends in the modeling results require that the temperature dependence in the kinetic isotope effect come from temperature dependence in the rate for deuterium transfer, since the rate for protium transfer in all cases (wild type SLO and mutants) is nearly temperature independent. Naturally, this requires a greater discrepancy between r0 and r* for the transfer of deuterium than for the transfer of protium. This discrepancy is what ultimately determines the force constant for the gating mode, since values of rX between 0 and r0 − r* must be thermally accessible. Excited states also have an effect on ΩX since r* is affected by quantum number. From Table 1, it can be seen that ΩX is lower for the gating model when Morse oscillators are used. The reason for this trend lies in the values of r* as a function of the isotope transferred. Table 3 illustrates the trends in measures of r* in the gating model used to fit data for wild type SLO and two mutants. Larger discrepancies between r0 and r* are observed for both deuterium and protium transfer when the hydrogenic wells are modeled using Morse oscillators. Ultimately, this is the result of a softening of the decay of Morse oscillator overlap as a function of well separation. This effect is also manifest in the disparities seen between r* for protium transfer and deuterium transfer with the harmonic and Morse oscillators. Protium hydrogenic wavefunctions experience a greater anharmonicity than deuterium wavefunctions in the Morse oscillator model, so the difference in wavefunction dispersion between protium and deuterium wavefunctions is greater than in the harmonic oscillator model.

Table 3. Distance of most probable transfer (r*) for wild type SLO and two mutants as a function of quantum number (n) of the acceptor wavefunction and type of model employed for the hydrogenic wells.

| Wild type SLO | Ile553 → Ala | Ile553 → Gly | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r*(H) (Å) | r*(D) (Å) | r*(H) (Å) | r*(D) (Å) | r*(H) (Å) | r*(D) (Å) | |

| Harmonic oscillator | ||||||

| r0 = 0.75 Å | r0 = 1.74 Å | r0 = 2.87 Å | ||||

| n = 0 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| n = 1 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.86 | 0.72 | 1.02 | 0.83 |

| n = 2 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 0.74 | 1.04 | 0.84 |

| n = 3 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 1.05 | 0.86 |

| n = 4 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 1.06 | 0.87 |

| n = 5 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.91 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 0.89 |

| Morse oscillator | ||||||

| r0 = 1.02 Å | r0 = 2.34 Å | r0 = 3.35 Å | ||||

| n = 0 | 0.93 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 0.89 | 1.39 | 1.03 |

| n = 1 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 1.18 | 0.93 | 1.45 | 1.08 |

| n = 2 | 0.94 | 0.91 | 1.23 | 0.97 | 1.51 | 1.13 |

| n = 3 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 1.28 | 1.01 | 1.58 | 1.18 |

| n = 4 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 1.33 | 1.06 | 1.66 | 1.24 |

| n = 5 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 1.39 | 1.10 | 1.74 | 1.29 |

Also shown is the distance (r0) between hydrogenic wells at the equilibrium position of the gating mode (rX = 0) for both the harmonic oscillator and Morse oscillator models.

4. Discussion

4.1. Heuristic argument for origin of gating modes

Modeling wild type SLO with the inclusion of gating modes provides insight into the possible function of such modes in SLO mutant proteins. What is perhaps most meaningful is that there is relatively little difference between r* and r0 for the wild type enzyme. Correspondingly, the gating frequency is on the order of kBT at room temperature . Obviously, the gating mode isn't contributing significantly to the space explored prior to the non-adiabatic tunneling event. Perhaps the best descriptor of how much range of motion is allowed by the presence of the gating mode is the root mean square of the displacement of the gating coordinate, rX, given by Eq. (7). Eq. (7) is equivalent to a measure of variance, , in the classical position distribution for the harmonic oscillator given in Eq. (3) in [23]. Table 4 gives a list of these values computed for wild type SLO and mutant proteins using both harmonic and Morse oscillator models for the hydrogenic wells. Deuterium transfer in mutant proteins requires a situation in which the promoting mode has a small force constant. Heuristically, the mutation can be thought of as providing a ‘defect’ in what was an evolutionarily optimized system. In other words, because the mutations disturb packing in the enzyme–substrate complex, a number of normal modes in the enzyme–substrate complex experience a change in ‘rigidity’. In general, because packing is no longer optimized, it might be expected that the enzyme–substrate complex would, over-all, be less rigid. This situation could predictably be expected to reduce the force constant associated with any modes that facilitate the hydrogenic wave function overlap. In the context of this model, small changes in hydrophobic side chains within an enzyme active site can have a very significant impact on tunneling efficiency.

Table 4. Root mean squared displacement of the gating coordinate at 298.15 K.

| Wild type SLO | Ile553 → Val | Ile553 → Ala | Ile553 → Gly | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morse oscillator | 0.08 Å | 0.17 Å | 0.19 Å | 0.24 Å |

| Harmonic oscillator | 0.03 Å | 0.12 Å | 0.13 Å | 0.19 Å |

| (7) |

While it might be argued that r0 is too small for wild type SLO in the harmonic oscillator model (vide infra), it is obvious that some values of r0 are quite large for some of the mutants, especially in the Morse oscillator model. It might be reasonably expected that, if gating mode force constants are generally reduced upon a disturbance in enzyme–substrate complementarity, modes which are asymmetrically coupled to the hydrogen transfer coordinate would also experience a reduction in force constant. Fig. 5 indicates that a change in the reorganization energy impacts the values of r0 that best fit the variation of KIE with respect to temperature decrease. The trends in Fig. 5 show that in the event that λ is decreased for the mutant SLOs, r0 would be decreased as well. While it is true that utilizing reorganization energy as an adjustable parameter could yield more ‘realistic’ values for r0, there is currently no reliable quantitative manner in which to do so. For this reason, the reorganization energy was kept constant at 19.5 kcal/mol for both wild type and SLOs. Similarly, there may be small changes in the reaction driving force, ΔG0, in moving from wild type enzyme to each of the mutants.

Fig. 5.

Variation of r0 with respect to reorganization energy for two mutants and wild type SLO using a Morse oscillator. Reorganization energies ≤20 kcal/mol may be appropriate to the SLO mutants, since increased values for λ lead to very large values for r0.

The net hydrogen transfer catalyzed by SLO is most accurately described as a proton-coupled electron transfer; however, no intermediates with a net change in charge from the reactants are anticipated to accumulate based on energetic considerations [45]. This distinction is important, since it has been shown experimentally that, in charge transfer reactions, enzymes reduce reorganization energy as a means of achieving catalysis [57]. Further, a disturbance in the pre-organization of the active site has been shown to raise λ. By contrast, the pre-organized architecture of electrostatics within the active site of an enzyme catalyzing hydrogen atom transfer may be small, with the result that changes in reorganization energy may be more tightly linked to changes in rigidity in the enzyme–substrate complex.

4.2. Concerns regarding distance of most probable transfer

In a previous model of wild type SLO [36], also based on [36], r0 was found to be 0.6 Å using harmonic oscillators to model hydrogenic wells. Because this implies a separation between the hydrogen donor and acceptor atoms that is less than van der Waals separation, the model was criticized [46]. In the current study, 5 reactant and product excited states were employed, and a global search was used to find the best fit to the temperature dependence of the KIE. With these modifications, the harmonic oscillator model yields a value of 0.75 Å for r0. However, accounting for reasonable estimates of O–H and C–H bond lengths, this still implies a C–O separation between the Fe(III)–OH cofactor and the C11 of linoleic acid of 2.8 Å, which is less than the estimated sum of van der Waals radii for O and C of 3.22 Å. With the inclusion of 5 excited states and anharmonicity, r0 was raised to 1.02 Å, making the C–O distance at the equilibrium position of the promoting mode about 3.07 Å. And, as shown in Fig. 5, this distance in wild type SLO can be further extended by increasing estimates of λ. Incidentally, raising the value of λ to 25 kcal/mol increases r0 to 1.20 Å, resulting in an equilibrium C–O distance of 3.25 Å. While this value exceeds the van der Waals separation, there are three considerations that might serve to place this value in perspective.

The first consideration concerns the predominate goal of the modeling study presented here and in [36]. Rather than embarking on a curve-fitting exercise for the purpose of reproducing experimental values, the current study seeks to understand the physical implications of parameter sets. It has been successfully shown that, by varying r0, ΩX, and λ, one can arrive at a reasonable set of parameter values to successfully replicate the temperature dependence of the KIE for wild type SLO and four of its Ile553 mutants. This approach to modeling the mutant Ile553 mutants was undertaken in an effort to understand how a decrease in the size of a hydrophobic side chain can induce a temperature dependence in the KIE that was not seen in the wild type enzyme. Furthermore, how can this situation arise without the rates or temperature dependencies for protium transfer changing very significantly in the mutants? The obvious physical answer is that some thermally sensitive process is driving deuterium transfer that is distinct from the reorganization energy and driving force terms. The concept of a gating mode coupled with the hydrogen transfer coordinate is a physically viable explanation for such behavior [13,14,23,27,28,37,40,42,58–60]. It is instructive to note that, as more drastic structural changes were made to Ile553, the less optimized complementarity of the enzyme–substrate complex resulted in parametric fits to the experimental data that show a reduction in the gating frequency. Likewise, estimates of r0 increase as the perturbations of the structure of Ile553 increase. This seems reasonable, with the caveat that estimates of the gating frequency and r0 are given as an expression of the physical origins of trends observed in the mutant series and are not intended to be interpreted in a strictly quantitative manner.

The second consideration with respect to short transfer distances in wild type SLO derives from the definition of van der Waals radii. This measure for the size of atoms is obtained using the average of non-bonding distances for a given type of atom. While the C11 carbon on linoleic acid may more or less be representative of carbons used to arrive at the value of 1.70 Å for carbon, it is unlikely that the oxygen in the Fe(III)–OH cofactor has as large a steric presence as an oxygen in an ether or ester, typical oxygen-containing molecules from which the van der Waals radii were estimated. Although, van der Waals radii may be reasonable for estimates of plausible approach distances between hydrogen donors and acceptors, they are probably not reliable when one of these atoms is involved in a bonding motif that is not well-represented in crystallographic databases.

A final thought with regard to transfer distance arises from the preponderance of short C–H⋯O distances that have been found in crystallographic studies of small molecule crystals [61–64]. A discussion of whether these interactions are hydrogen bonds is largely a matter of semantics. What is important in the context of the current study is that attractive interactions appear to allow a closer approach of the donor and acceptor atoms. In fact, a C–O distance as low as 2.94 Å has been reported in one crystal structure [62]. Short C–H⋯O distances (≤3 Å) have also been found in a number of protein crystal structures [65,66]. Given that this type of attractive interaction occurs naturally, it is reasonable to expect that donor/acceptor C–O distances of ≤3 Å may occur through some kind of attractive interaction in SLO without the requirement of an energetically unfavorable enzyme–substrate complex.

4.3. Connections with other models

The hydrogen transfer catalyzed by soybean lipoxygenase has been modeled by many groups. First, three simple calculations of an adiabatic potential energy surface for the net hydrogen transfer will be considered. Tresadern et al. [11] modeled the Fe(III) cofactor with its three ligands (His504, His499, and His690) represented as imidazoles, Asn694 represented by acetamide, and Ile839 by acetate. The substrate is modeled as 1,4-pentadiene. They employ a semi-empirical method (PM3/d) for computation of energies, finding a local minimum for the reactant with a C–O distance of 2.95 Å. In addition to computing the reaction coordinate, Tresadern et al. [9] compute the primary deuterium KIE using a small curvature tunnel correction. Lehnert and Solomon [67] utilized a structurally less appealing model for the Fe(III) cofactor and its ligand set but used what is generally considered to be a better theoretical method for computing structure: density functional theory. Their model utilized ammonia molecules in place of the three coordinating histidines, formamide in place of the Asp694, and formate in place of the terminally coordinating Ile. Linoleic acid was modeled using (Z,Z)-2,5-heptadiene. The substrate positioning was achieved using the anticipated substrate channel in the 1YGE [68] crystal structure of SLO and the binding motif of an inhibitor in the 1LOX [69] protein database structure of mammalian 15-lipoxygenase. The resulting substrate binding motif resulted in an enzyme–substrate complex with a donor/acceptor atom distance of 3.0 Å; no attempt was made to compute the primary kinetic isotope effect for the net hydrogen abstraction. Borowski and Brocławik [70] computed the transition structures and potential minima for the entire reaction pathway for SLO-catalyzed oxidation of linoleic acid, using structure and theoretical approaches similar to Lehnert and Solomon's work; however, they did not focus on the nature of the hydrogen abstraction step and only computed the energy of activation and energy change for this step.

Perhaps more germane to the current study are the investigations where the hydrogen transfer is treated quantum mechanically. Hatcher et al. [45] have utilized a multistate valence bond treatment of proton-coupled electron transfer [24–26] to model the net hydrogen transfer catalyzed by wild type SLO. This model represents two major refinements of the simple model used in the current study. First, the electronic coupling is dependent upon the position of the proton in their model; whereas, in our model electronic coupling is constant. Second, in addition to the protonic overlap, the reorganization energy and electronic coupling are dependent upon the donor/acceptor distance. While this model is more descriptive and more physically ‘correct’ than the Kuznetsov–Ulstrup model, it suffers from the need for more parameters. The EVB Hamiltonian has 10 unique elements which all depend upon the donor/acceptor distance. Both the gating mode and the hydrogenic vibrational wavefunctions are represented by Morse potentials. Interestingly, Hatcher et al. computed inner sphere reorganization energy associated with the change in position of the Fe(III) ligand set and found the value to be 19.1 kcal/mol, which is very near the value of 19.5 kcal/mol used in the current study and earlier work [36]. Outer sphere reorganization energy was found to be about 1.9 kcal/mol for the lowest energy reactant and product proton-coupled electron transfer states, resulting in a total reorganization energy of 21.0 kcal/mol. Hatcher et al. performed docking studies using Autodock [71] to establish a suitable orientation of the linoleic acid within the active site of SLO. The equilibrium C–O distance used was 2.88 Å, and the dominant transfer distance was found to be at a C–O separation of 2.69 Å. This value is significantly lower than the relevant distances computed in this study of about 3.07 Å for the equilibrium C–O distance and 2.98 Å for the C–O distance of most probable transfer. However, by using a lower forcing vibration frequency of 300 cm−1, Hatcher et al. were able to achieve an equilibrium C–O distance of 3.1 Å. Perhaps the most puzzling result of the multistate continuum model was the use of a forcing vibration with a force constant of 36–101 J m−2 versus the value in the current study of 181 J m−2. While the disparity in these values is not overwhelming, it indicates that the gating vibration was of greater necessity in achieving net hydrogen transfer in the model of Hatcher et al.

Siebrand and Smedarchina [46] have also modeled wild type SLO and one mutant (the Ile553 → Ala). However, they modeled the data for both enzymes collectively, based on the belief that the kinetic data were statistically indistinguishable. By the nature of the experiments in which the temperature dependence of the rate is determined, the results display significant scatter. However, it is helpful to understand how the experiments are carried out in order to evaluate the validity of the temperature dependence in the isotope effect. Scatter in the individual rates as a function of temperature is generally larger than the scatter in the isotope effect measurement. This is because the rate data at a given temperature are determined at the same time for both the deuterated and protiated substrates, so any variability in rates for protiated and deuterated substrates that arises due to inconsistent enzyme activity is accounted for in the measure of the isotope effect itself. For this reason, the estimates of ΔEA that are computed from the temperature dependence of the KIE have reliable error bounds. Given this information, the wild type and Ile553 → Ala mutants are quite distinct in the temperature dependence of the isotope effect (Table 1). The additional data collected for Ile553 → Val and Ile553 → Gly corroborate the original findings with the Ile553 → Ala, that the temperature dependence of the KIE is decreasing with the generation of active site packing defects. Siebrand and Smedarchina model the data using two theories. The first is a Golden Rule approach that is indistinguishable in form from the one used here. The second is an instanton approach [13,14]. Because no details regarding the instanton model and the selection of parameters were given, we focus on the details and results of the Golden Rule calculation. Although Siebrand and Smedarchina use Morse potentials for the hydrogenic wells, they did not utilize any vibrational excited states. Also, instead of deriving the anharmonicity of the Morse potentials from physically realistic bond dissociation energies, they utilized an adjustable parameter that was varied between 60 and 100 cm−1. In the present study, the anharmonicity of the hydrogenic wells for protium in the current study is 80.2 cm−1 and is derived from a dissociation energy of 80.3 kcal/mol (vide supra). At the upper limit of the anharmonicity explored by Siebrand and Smedarchina, the value of r0 was found to be 1.0 Å. This value would have been substantially larger if excited vibrational states had been included. The free energy of the reaction was also utilized as an adjustable parameter and varied between −10 and 10 kcal/mol. In terms of discussing the physical implications of the model, Siebrand and Smedarchina focused on the meaning of the short values of r0 computed in their study. As discussed above, the distance of 1.0 Å found in their study is not short enough to demand a physically unique explanation. Even though van der Waals radii are used to place a lower bound on this value, the applicability of such a measure is questionable given the way in which van der Waals radii are computed. We further note that the transfer distances computed herein may be reduced through the use of a reorganization energy that is somewhat underestimated. Hatcher et al. obtained a slightly larger reorganization energy than the one assumed in the present study even without the consideration of inner sphere reorganization within the bonding framework of the linoleic acid substrate. The inclusion of such a measure might push the reorganization energy estimates toward the value of 25 kcal/mol, for which the value of r0 is large enough to allow a C–O distance in excess of the sum of the oxygen and carbon van der Waals radii.

5. Concluding comments

SLO and three Ile553 mutants were modeled using a computational scheme that considered three distinct coordinates: the solvent coordinate, the gating coordinate, and the hydrogen transfer coordinate. The hydrogenic wells that form the termini of the hydrogen transfer coordinate were modeled both as harmonic oscillators and Morse oscillators. The effects of two parameters (r0 and ΩX) upon the temperature dependence of the primary deuterium KIE were explored fully for each mutant and the wild type enzyme. Additionally, the effect of reorganization energy upon the best parametric fit of r0 was explored. The hypothesis originally tested in this work was whether the inclusion of a gating vibrational mode could be used to model the observed effects of mutation at Ile553 upon the temperature dependence of the KIE. It was found that structural alterations in Ile553 corresponded with a decrease in ΩX and an increase in r0 consonant with the degree of structural perturbation at the native Ile553 position.

Two concerns with regard to estimates of r0 were addressed. For the harmonic oscillator model of hydrogen transfer in wild type SLO, an equilibrium donor/acceptor well separation of 0.75 Å was found to best reproduce the magnitude and temperature dependence of the KIE. However, this value is small enough to consider alterations to the model that, while maintaining a reasonable physical picture, would allow for a longer equilibrium donor/acceptor distance. The incorporation of Morse potentials to model the hydrogenic wells was found to be a reasonable approach, increasing r0 to 1.02. It was also shown that excited acceptor states are important determinants in the hydrogen transfer rate and associated KIE, with their inclusion extending r0 beyond that which would be measured for a 0 → 0 transfer.

Aside from the concerns about low estimates for r0 in wild type SLO, the large value for the same parameter in the Ile553 → Gly mutant seems unreasonable. We considered the possibility that reductions in the force constant for the gating mode could be accompanied by concomitant changes in the force constant for vibrations that determine the relative energies of the reactant and product wells (Fig. 3B). This led to a systematic study of how changes in reorganization energy affect values of r0. When λ is lowered, parametric fits yield lower estimates for r0. Likewise, raising λ results in an increased equilibrium hydrogenic well separation. For wild type SLO, one can achieve donor/acceptor distances that exceed the sum of van der Waals radii by increasing the reorganization energy by about 5 kcal/mol. In summary, while the model employed here lacks some utility as a predictive model, it is very useful in aiding our understanding of the multi-dimensional nature of tunneling and the physical processes that underlie the experimental observables obtained in the systematic exploration of the temperature dependence of KIEs in wild type and mutant SLO enzymes. These studies also illustrate how a single residue (Ile553) that is 13 Å removed from the active site Fe(III)–OH in SLO can influence the environmental dynamics that play such a critical role in efficient hydrogen transfer.

References

- 1.Hydrogen transfer is used in this paper as a generic term for proton, hydride, and hydrogen atom transfer.

- 2.Eyring H. Trans Faraday Soc. 1938;34:41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truhlar DG, Isaacson AD, Garrett BC. In: Theory of Chemical Reaction Dynamics. Baer M, editor. Vol. 4. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 1985. p. 65. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truhlar DG, Garrett BC, Klippenstein SJ. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:12771. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truhlar DG, Garcia-Viloca M, Gao J, Karplus M. Science. 2004;303:186. doi: 10.1126/science.1088172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell RP. Trans Faraday Soc. 1959;55:1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell RP. The Tunnel Effect in Chemistry. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Northrop DB. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:3521. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Truhlar DG, Liu YP, Schenter GK, Garrett BC. J Phys Chem. 1994;98:8396. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu YP, Lynch GC, Truong TN, Lu DH, Truhlar DG, Garrett BC. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:2408. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tresadern G, McNamara JP, Mohr M, Wang H, Burton NA, Hillier IH. Chem Phys Lett. 2002;358:489. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rickert KW, Klinman JP. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12218. doi: 10.1021/bi990834y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benderskii VA, Goldanskii VI, Makarov DE. Phys Reports. 1993;223:195. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benderskii VA, Makarov DE, Wight CA. Adv Chem Phys. 1994;88:1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trakhtenberg LI, Klochikhin VL, Ya Pshezhetsky S. Chem Phys. 1981;59:191. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dogonadze RR, Kuznetsov AM, Levich VG. Electrochim Acta. 1968;13:1025. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dogonadze RR, Kuznetsov AM. J Theor Biol. 1977;69:239. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(77)90134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brüniche-Olsen N, Ulstrup J. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans I. 1979;75:205. [Google Scholar]

- 19.German ED, Kuznetsov AM. J Chem Soc Faraday Trans II. 1980;76:1128. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jortner J, Ulstrup J. Chem Phys Lett. 1979;63:236. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siebrand W, Wildman TA, Zgierski MZ. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:4083. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sumi H, Ulstrup J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;955:26. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(88)90176-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuznetsov AM, Ulstrup J. Can J Chem. 1999;77:1085. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soudackov A, Hammes-Schiffer S. J Chem Phys. 1999;111:4672. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soudackov A, Hammes-Schiffer S. J Chem Phys. 2000;113:2385. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hammes-Schiffer S. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:273. doi: 10.1021/ar9901117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgis DC, Lee S, Hynes JT. Chem Phys Lett. 1989;162:19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borgis DC, Hynes JT. Chem Phys. 1993;170:315. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iordanova N, Hammes-Schiffer S. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4856. doi: 10.1021/ja017633d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cukier RI. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:1746. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glickman MH, Wiseman JS, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:793. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Glickman MH, Klinman JP. Biochemistry. 1995;34:14077. doi: 10.1021/bi00043a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glickman MH, Klinman JP. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12882. doi: 10.1021/bi960985q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonsson T, Glickman MH, Sun SJ, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:10319. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glickman MH, Cliff S, Thiemens M, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:11357. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knapp MJ, Rickert K, Klinman JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3865. doi: 10.1021/ja012205t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuznetsov AM, Ulstrup J. Electron Transfer in Chemistry and Biology: An Introduction to the Theory. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marcus RA. J Chem Phys. 1956;24:966, 979. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levich VG. In: Physical Chemistry: an Advanced Treatise. Eyring H, Henderson D, Jost W, editors. IX. Academic Press; New York: 1970. p. 985. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benderskii VA, Philippov PG, Dakhnovskii YuI, Ovchinnikov AA. Chem Phys. 1982;67:301. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mincer JS, Schwartz SD. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:7755. doi: 10.1063/1.1690239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caratzoulas S, Schwartz SD. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:2910. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caratzoulas S, Mincer JS, Schwartz SD. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:3270. doi: 10.1021/ja017146y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cui Q, Karplus M. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:7927. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hatcher E, Soudackov AV, Hammes-Schiffer S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5763. doi: 10.1021/ja039606o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siebrand W, Smedarchina Z. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:4185. doi: 10.1021/jp2022117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cohen-Tannoudji C, Liu B, Laloë F. Quantum Mechanics. Vol. 1. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1977. p. 586. [Google Scholar]

- 48.http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/∼cchieh/cact/c120/bondel.html.

- 49.Bondi A. J Phys Chem. 1964;68:441. [Google Scholar]

- 50.McMillen DF, Golden DM. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 1982;33:493. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morse PM. Phys Rev. 1929;34:57. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rong Z, Kjaergaard HG, Sage ML. Mol Phys. 2003;101:2285. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arfken GB, Weber HJ. Mathematical Methods for Physicists. Academic Press; San Diego: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curvatures of the Harmonic and Morse potentials were chosen to correspond to a harmonic energy spacing of 3000 cm−1 for both reactant and product hydrogenic wells.

- 55.M.P. Meyer, J.P. Klinman, in preparation.

- 56.Streitweser A. Molecular Orbitals for Organic Chemists. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roth JP, Klinman JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252644599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruno WJ, Bialek W. Biophys J. 1992;63:689. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chantranupong L, Wildman TA. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4151. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chantranupong L, Wildman TA. J Chem Phys. 1991;94:1030. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hobza P, Havlas Z. Chem Rev. 2000;100:4253. doi: 10.1021/cr990050q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bock H, Dienelt R, Schodel H, Havlas Z. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1993:1792. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jeffrey GA. An Introduction to Hydrogen Bonding. Oxford University Press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Desiraju GA, Steiner T. The Weak Hydrogen Bond. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ash EL, Sudmeier JL, Day RM, Vincent M, Torchilin EV, Haddad KC, Bradshaw EM, Sanford DG, Bachovchin WW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Derewenda ZS, Lee L, Derewenda U. J Mol Biol. 1995;252:248. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lehnert N, Solomon EI. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:294. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0415-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Minor W, Steczko J, Stec B, Otwinowski Z, Bolin JT, Walter R, Axelrod B. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10687. doi: 10.1021/bi960576u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gillmor SA, Villasenor A, Fletterick R, Sigal E, Browner M. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:1003. doi: 10.1038/nsb1297-1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borowski T, Brocławik E. J Phys Chem B. 2003;107:4639. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639. [Google Scholar]