Abstract

In 2007, the Department of Health and Human Services commissioned the Nationwide Health Information Network (NHIN) Trial Implementations project to demonstrate the secure exchange of data among health information exchange organizations around the country. The project's Core Services Content Work Group (CSCWG) developed the content specifications for the project. The CSCWG developed content specifications for a summary patient record and for eight use cases that were implemented in demonstration events in 2008. The CSCWG developed tools to represent the specifications and facilitate implementation. The experience revealed that, in general, the Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP) constructs served as a suitable starting point for the development of content specifications for interoperability. The ability to adhere to specified terminologies still presents significant challenges. This paper describes the process of developing the content specifications and lessons learned.

Introduction

Interoperability is a key requirement for modern health information technology.1 Many patients receive care in multiple locations and even if the health data are maintained electronically, the lack of interoperability impedes access to data, which in turn can lead to inefficiencies, increased costs, and poor quality.2 3 4 5 Interoperability increases the value proposition of electronic health record (EHR) systems because it enables the EHR to be used as a “window” onto all of the patient's data rather than simply automating local workflow processes. Efforts to develop and promote health data standards, which are critical for interoperability, have been underway for decades but progress has been limited due in part to the absence of any central coordination function.6 In some cases, a collection or “suite” of standards used in a coordinated way is necessary to accomplish a particular workflow task in an interoperable manner.7 Technical efforts to advance interoperability need to progress hand in hand with the development of policy and programmatic efforts that leverage interoperable health information for care improvement and address shortcomings of the health system; these policy and programmatic efforts in turn will further accelerate the development of technical interoperability capabilities.8

In 2004, when President Bush called for the widespread use of interoperable electronic health records (EHRs) by 2014, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) responded by creating a Strategic Framework to advance the development of a nationwide health information network (NHIN).9 The four goals of the framework were: (1) to increase the use of EHRs and other automated information tools in clinical practice; (2) to enable interoperability among healthcare stakeholders; (3) to use information tools to help personalize care delivery; and (4) to advance surveillance and reporting for population health improvement. Among the efforts to advance this work, ONC commissioned the Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP) to harmonize the health information technology standards relevant to interoperability.10 In 2005, ONC funded four consortia to develop prototype architectures for the nationwide health information network.11 A report in 2007 on the results of these efforts12 affirmed that the use of common standards is a critical prerequisite to the development of the NHIN.

In 2007, ONC commissioned a second phase of the NHIN project known as the NHIN Trial Implementations. The goal of the second phase was to demonstrate the secure exchange of clinical data among nine health information exchanges (HIEs) from around the country. Collectively, the participants were known as the NHIN Cooperative. Six additional participants joined the NHIN Cooperative in 2008, as well as four Federal agencies. The goal of the NHIN Trial Implementations project was successfully realized in a testing event in August 2008, and public demonstration events in September and December 2008 when electronic patient data were exchanged among Cooperative members using NHIN-conformant specifications. The data in these events were de-identified test data since the NHIN trust fabric was being established in parallel as part of the NHIN Trial Implementations project.

A key facet of the NHIN Trial Implementations project was the development of content specifications to promote both syntactic (structural) and semantic (meaning) interoperability among the members of the NHIN Cooperative. Each Cooperative member had to represent the data using the developed specifications and had to be able to successfully complete conformance and interoperability testing and exchange data with the other members. This paper describes the development of the data specifications, including (1) the work group structure used to develop the specifications, (2) the process for creating the content specifications for a “summary patient record” and eight additional use cases, and (3) lessons learned during the process that might inform future activities.

Structure of the NHIN Trial Implementations Project

Overview

The objective of the NHIN Trial Implementations project was for the participant health information exchange (HIE) organizations to:

Deliver a “summary patient record” to another HIE.

Be able to identify where data are available for a particular individual in other HIEs and retrieve data for that individual.

Exchange consumer access permissions (eg, a consumer's decision to participate or not to participate in the exchange).

Support secondary uses of data, especially for population uses.

Work groups composed of individuals from the participant organizations were formed to address the following tasks:

Develop specifications for technical core services including infrastructure, identity, and consumer services (Technical and Security Work Group).

Develop data specifications including content of all payloads exchanged (Core Services Content Work Group).

Coordinate testing activities (Testing Work Group).

Develop a data use and reciprocal support agreement (DURSA Work Group) and identify expectations for trust among NHIN Cooperative participants.

This paper describes the work done by the Core Services Content Work Group (CSCWG); two of the authors (GK and JB) chaired this Work Group.

The project term was from September 2007 to January 2009. In February 2008, the scope was expanded to include the implementation of priority scenarios from seven use cases that had been developed by the American Health Information Community (AHIC, now the National eHealth Collaborative), as well as a use case developed by the Social Security Administration (SSA).13 Although demonstrating the ability to exchange a summary patient record was a requirement for all members of the NHIN Cooperative, each use case was implemented by only one or two Cooperative members. The exchange of the summary patient record demonstrated the NHIN infrastructure and core foundational services; the use cases demonstrated the ability of the NHIN to support more complex business needs of healthcare.

Organization of the Core Services Content Work Group

The charge to the Core Services Content Work Group (CSCWG) was to develop the specifications for the content (data) requirements that would be implemented by the Cooperative members in a demonstration event. The data specifications were to identify:

The data elements to be exchanged.

Suitable terminologies for the data elements.

Business rules relevant to the data elements, for example, whether a data element was required, whether it could repeat, etc.

The starting point was the data specifications that had been created by the Health Information Technology Standards Panel (HITSP).14 In response to use cases that had been created by the AHIC, HITSP created Interoperability Specifications (ISs), which model the functional requirements and lay out the technical requirements for the use case. Details of ISs and the enabling technical specifications can be found on the HITSP website.15 An implicit goal of the NHIN Trial Implementations project was to implement and verify the suitability of the HITSP constructs as proposed in the ISs; HITSP provided a facilitator to the CSCWG to assure that the intent and details of the HITSP constructs were communicated to the work group.

The CSCWG was required to create:

A data content specification for the summary patient record.

A data content specification for each use case.

The CSCWG met weekly by phone for 90 min from November 2007 until July 2008. The summary patient record specification was delivered in April 2008 and the use case specifications were delivered in July 2008.

Creating the specifications

Creating the summary patient record specification

The instructions to the CSCWG from ONC were that the content specifications of the summary patient record16:

be based on the AHIC Emergency Responder Electronic Health Record (ER-EHR) use case17;

identify a “minimal data set” that would be of value to a clinician arriving at the scene of an accident if the clinician knew nothing about the patient and that could support coordination of care between care providers;

include values for optionality, repeatability, and the allowable value sets for the data elements.

After carefully reviewing the ER-EHR use case (HITSP/IS04),18 the CSCWG chose to focus on the HITSP/C32 construct,19 a document-oriented summary record specification to enable exchange of administrative and clinical data among such systems as personal health records (PHRs), EHRs, practice management systems, and other applications. The HITSP/C32 is based on the Health Level 7 (HL7) Continuity of Care Document (CCD).19 The CCD maps the data elements of the Continuity of Care Record developed by ASTM20 into a Clinical Document Architecture (CDA)21 representation.

The HITSP/C32 document consists of 17 modules, shown in box 1. A module contains multiple patient data elements. Attributes of each data element include an optionality flag, a repeating flag, and the data source. The optionality flag indicates whether the data is required and the repeating flag indicates whether the field may repeat (eg, multiple phone numbers or addresses). The data source describes how the data field should be represented, for example, free text or a member of an enumerated “value” set. Value sets are subsets of terminologies or vocabularies that limit the possible values a data element can take.

Box 1. Modules of HITSP/C32.

Person information

Language spoken

Support

Healthcare provider

Insurance provider

Allergy/drug sensitivity

Condition

Medication—prescription and non-prescription

Pregnancy

Information source

Comment

Advance directive

Immunization

Vital sign

Result

Encounter

Procedure

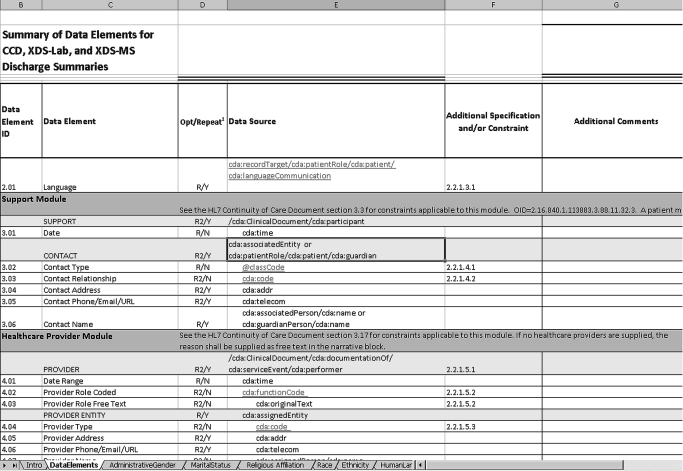

For easy navigability, a representation of the HITSP/C32 construct was created in an Excel spreadsheet.22 A portion of the spreadsheet is shown in figure 1. Altogether, there were 155 data elements, 48 data elements with a HITSP-specified value set, 58 required data elements, and 16 that were both required and have an HITSP-specified value set. A textual description of the contents of the spreadsheet was included as part of the specification document.16

Figure 1.

Sample of spreadsheet used to describe the content specification for the Summary Patient Record.

For a minimal data set, the Work Group selected six of the 17 HITSP/C32 modules based on descriptions in HITSP/IS04:

Module 1—Person information module.

Module 3—Support module (emergency contact information).

Module 6—Allergies and drug sensitivities module.

Module 7—Conditions module (problem list).

Module 8—Medications module.

Module 10—Information source module.

These modules were required to be included in the data transmission if they were available; a value of “null” had to be sent if the data was not available.

The Work Group decided that the HITSP-specified optionality and repeatability flag for a field in the summary patient record should be adhered to as stated in the HITSP/C32 document.

With respect to value sets for the six required modules in the minimum data set, the Work Group decided that if the HITSP/C32 construct specified a value set, the use of the value set would be required. For the data elements in the 11 optional data modules, if the HITSP/C32 construct specified a value set, the use of the value set was made optional. The rationale for this decision was that the data elements in the required data modules ostensibly are more important and semantic interoperability would be guaranteed. In the other data modules, the data element at least could be displayed. When the HITSP/C32 specification allowed for multiple value sets (eg, for Medication Product codes) or did not specify a value set (eg, for Procedure Codes) the CSCWG, with the assistance of the HITSP facilitator, selected a value set for the specification.

The specification was not intended to be an implementation guide. Users of the specification were referred to a Continuity of Care Document (CCD) implementation guide23 and finally to the Clinical Document Architecture R221 schema for the exact data formats. Implementers were also referred to the website of the National Institutes for Standards and Technology (NIST), which has testing tools, code samples, and other resources for implementers.24 References for best practices in implementing CDA and CCD standards were also provided to the implementers.16 The Core Services Content Work Group and the Testing Work Group had frequent interactions to assure that the testing processes would be aligned with the content specifications.

Creating content specifications for the use cases

Overview

The Core Services Content Work Group also created content specifications for the eight use cases. As mentioned, the use cases were developed by AHIC to demonstrate business value from health information exchange. These use cases were:

EHR: laboratory results—communicate new laboratory results to an EHR.

Emergency responder—provide clinicians in an emergency setting with access to data.

Medication management—enable medication reconciliation and provide access to medication and allergy data.

Quality—communicate quality related data from a provider to a central data collection entity.

Biosurveillance—communicate data to support situational awareness, event detection, and outbreak management scenarios.

Consumer empowerment: consumer access to clinical information—enable a consumer to access his or her clinical data via a PHR.

Consumer empowerment: registration/medication history—enable the consumer to use a PHR to provide his or her care providers with medication history and basic registration information in advance of an encounter.

SSA: authorized release of information—provide access to clinical data to the SSA for disability benefits determination.

For each use case, detailed functional requirements (including data requirements) were created. Then content specifications were developed from the functional requirements. The content specifications were developed by small teams that included representatives from each use case work group and representatives from the CSCWG.

Whenever possible, use case specifications used the summary patient record specification as a starting point. Reuse of the summary patient record specification reduced development time and limited the variation in document formats. Each use case team determined if additional data elements, different value sets, and/or different optionality or repeating flags were required. HITSP constructs other than the HITSP/C32 could be referenced.

Content specifications for the use cases

Two of the use cases—Emergency responder and Consumer access to clinical information—used the summary patient record specification without any changes. This is because these use cases simply needed a summary of the patient's data. Four of the use cases were able to use the summary patient record specification as a starting point, but were required to make some extensions to fulfill the needs of the use case:

Medication management. The Provider and Insurance modules of HITSP/C32 were required.

SSA: authorized release of information. The optionality of some modules (healthcare provider, vital sign, results, encounter and procedure) were changed to “required if known”. Four other data fields (procedure date, procedure code, medical equipment code and medical equipment name) were required.

Consumer empowerment: registration and medication history. Optionality of certain data elements related to family and social history were required so a complete medication risk profile could be represented.

EHR: laboratory results. Although the summary patient record specification representation of laboratory results is sufficient for data visualization (ie, display on a web portal), it is not adequate for integrating the result with other laboratory results in an EHR system. A more detailed representation of laboratory test results, HITSP/C37 (based on the Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise [IHE] Laboratory Technical Framework25) was used for this use case.

Two use cases were not able to use the summary patient record as a starting point and required completely different approaches. For the Biosurveillance use case,26 to enable the transmission of health data to public health agencies, the team based the specification on the AHIC Biosurveillance Minimum Data Set.27 The team made use of HITSP/C36 to represent laboratory results, HITSP/C39 to represent encounter data, and HITSP/C47 to represent healthcare resources such as available beds. A data spreadsheet, similar to the one that had been created for the summary patient record, was created for this use case.28 These specifications are based on HL7 v2.5.1 messages, rather than the HL7 CDA document specification, primarily as a reflection of the current common practice among public health organizations performing biosurveillance activities.

The AHIC Quality use case29 included multiple information flows related to the transmission of quality related data (the numbers refer to the flows in the use case document):

Flow 1—The ability to communicate the quality measure itself. Does not contain any patient-related data.

Flow 3—Patient-specific data to that could be used determine if a patient is compliant with a quality measure.

Flow 4—Patient-specific quality data. For a given quality measure, whether the patient is compliant with that measure.

Flow 9—Population/aggregated quality measures. For a given quality measure, the proportion of the population in aggregate that is compliant with the measure.

For Flow 3, the summary patient record specification was chosen. For the other flows, the group settled on proposed representations from the Collaborative for Performance Measure Integration with EHR Systems30 to represent the information in Flow 1. The Quality Reporting Document Architecture31 was chosen to represent Flows 4 and 9.

Lessons learned

At events in September and December 2008, the Cooperative members demonstrated implementations of the final content specifications and technical services necessary to realize exchange of data.32 These events used scripted, clinically oriented scenarios. For example, at the September event, the Indianapolis health information exchange demonstrated the retrieval and display of data from other Cooperative members in the context of a fictional patient who had suffered a heart attack while visiting Indianapolis; and at the December event, the SSA demonstrated obtaining records electronically to assess disability eligibility. The next phase of the NHIN project, known as “Limited Production”,33 is continuing to use the content specifications that were developed for the Trial Implementations phase. Also, the SSA is using the Release of Information specification for its initiative to promote the use of electronic medical records for disability determination.34

Several lessons were gleaned from the experience of developing and implementing the content specifications.

First, the participating health information exchange organizations were able to implement the content specifications without major challenges. This demonstrated the technical feasibility of implementing the specifications that had been created.

Second, the project offered the opportunity to work with the documents that HITSP had been developing over several years and test them in an operational exchange setting. The HITSP constructs were suitable as a starting point for the summary patient record specification and across a diverse set of use cases. Most of the use cases could be represented by the summary patient record specification with little or no modification. This is not surprising since many work flows and decisions in healthcare depend on access to a summary of the patient's record. Also, prior to this project, a generally accepted minimum required specification for a summary patient record had not been identified. The summary patient record specification created here may serve as a consistent reference point as future needs to communicate among consumers, providers, EHRs and PHRs are articulated. The Biosurveillance and Quality use cases required completely different content specifications, so a broad perspective on what constitutes “healthcare information” will need to be kept in mind as specifications for interoperability are developed. Notably, no well accepted candidates existed for the representation of data for the Quality use case and, although the group was able to come to consensus, this experience highlights the fact that progress needs to be made in representing data in this as well as other critically important areas of healthcare. Also, while the HITSP constructs provided a rich starting point for the content of clinical documents to be exchanged over the NHIN, the requirements and vocabularies for the document metadata that would allow for convenient computer-aided searching for information within a patient's electronic health record needs to be expanded. The ability for the specifications to allow document subtypes, such as discharge summaries, progress notes, and postoperative notes to be represented will increasingly be important over time. Also, metadata vocabularies to allow information to be tagged as containing “sensitive” data that can facilitate appropriate restrictions being placed on access to that information will be important going forward. Practice setting, healthcare facility type and confidentiality codes also need continued development. These limitations were not a significant factor in the limited scenarios tested and demonstrated in the NHIN Trial Implementations, but likely would create limitations to usability as a patient's electronic records become more extensive and more widely distributed among care providers and HIEs.

The HITSP constructs could benefit from better documentation. It was not always clear how best to use the constructs and how different constructs could best be used together to achieve a certain goal. A significant investment of time was required to become familiar with the documents and only a subset of the work group developed a truly deep understanding of the various constructs. The HITSP facilitators played a critical role in conveying a thorough understanding of the documents.

Successful testing of the HITSP content constructs in the NHIN framework has increased the confidence that HITSP constructs will be able to address a broad set of requirements. Although developing constructs that would be useful in real-world settings had been the goal of HITSP's activities, the constructs had not been field tested previously among such a diverse group and in such a detailed manner. As more complex healthcare information exchange scenarios are developed, it may be reasonable to expect that HITSP constructs will be a suitable starting point for new interoperability specifications over the NHIN and other networks.

Third, tools for consistent mapping between terminologies are needed. As mentioned, there were 19 health information exchange organizations participating in the Trial Implementations project. These 19 represented many more individual distinct healthcare provider organizations. An informal survey conducted by the work group indicated a wide diversity in the data capabilities of the participating health information exchange organizations. While almost all organizations could provide enough data to create value, not all healthcare organizations could provide all the data specified in the summary patient record, and not all organizations could provide data in the specified value sets (terminologies). Health information exchange organizations will increase their capabilities to provide clinical data over time, however being able to provide data in specified terminologies (eg, SNOMED, RxNorm, LOINC, etc) is a significant challenge, mainly because the participants' source systems used proprietary concept identifiers and translation services were not readily available. Tools that allow translation from local proprietary concept identifiers to emerging standard identifiers, or between commonly used terminologies (eg, from the International Classification of Disease to SNOMED) would be immensely helpful to organizations trying to comply with emerging specifications. Such tools would also increase consistency of translation across organizations.

Fourth, the NHIN specifications appear to be a suitable technical foundation for vendors to build commercial HIE network solutions. It was noted that the technology partners of the members of the NHIN Trial Implementations Cooperative were beginning to build the specifications from the NHIN project into their standard offerings. This means the vendors are finding these specifications acceptable for production use and are not treating them as a “one-off” set of specifications, and the policy goal of encouraging vendors to adopt common protocols is being achieved. Interoperability showcases, such as that at the annual HIMSS conference,35 further demonstrate that standards are being adopted by commercial products.

Conformance testing to assure interoperability is non-trivial. The project's Testing Work Group worked with NIST to develop a Schematron-based tool to test compliance. Schematron is a rule-based language for making assertions about patterns in XML documents. These tools were not extensively used during the NHIN Trial Implementations, but this approach has been demonstrated in other settings.36 Future NHIN initiatives will need to include more robust approaches to testing.

Using a spreadsheet to create the specifications provided the appropriate level of detail for this project. Although commercial tools are available for specification documentation, the group did not think they would have added significant value for this project.

An important factor in the success of the initiative was the efforts, energy, expertise and collaborative spirit of the members of the Cooperative. A substantial amount of work—requirements analysis, issue resolution, standards harmonization, inter-workgroup coordination and test case generation—was accomplished within a brief period of time. The achievements were more than what a single HIE could have accomplished by itself. The fact that ONC empowered the members of the cooperative to make the recommendations invigorated and engaged the group. The group was also invigorated by the sense of opportunity to exercise the constructs in an operational setting and have the chance to advance the nation's learning on these important topics. ONC provided clear goals and helpful templates which helped the work group meet ONC's expectations. Also, HITSP was a critical contributor to the success of the initiative, helping to resolve issues regarding value sets and how to best make use of the constructs.

It should be noted that the content specifications developed for this project were intended simply to meet the goals of this project. Future initiatives may choose to use the specifications as is, or to modify them to suit their goals, as needs dictate.

Finally, in the course of the project, other content-related issues were identified that will need to be addressed by future interoperability initiatives, for example:

If there are to be terminology services in the NHIN, should those be architected centrally or distributed?

What are the proper policies and procedures for version control and management of the content standards for the NHIN?

When are document-oriented structures, as represented by the Clinical Document Architecture, suitable for interoperable content specifications, and when are message-based structures more suitable?

Concluding thoughts

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) commits substantial funds to the advancement of health information technology, including health information exchange. Meaningful use guidelines include an evolving vision for leading the nation toward an information infrastructure to support a transformed healthcare system. The HIT Standards Committee is focusing on the standards that are necessary to support ONC's goals for meaningful use. Many gaps in standards remain; however, the work described herein serves as an important foundation on which to take the next steps.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the NHIN Trial Implementations Core Services Content Working Group, liaisons from external organizations, and subject matter experts from the Use Case Work Groups that contributed to the development of the specifications described herein. For a complete list, please see Appendix 1, available as an online only data supplement at www.jamia.org.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Some of the content that appears in this paper has been previously published on the Department of Health and Human Services National Health Information Network Resources website (http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=1194&parentname=CommunityPage&parentid=2&mode=2&in_hi_userid=10741&cached=true). The US government, which was contractually obligated to publish the results, is the owner of the work on the website. The goal of this paper is to provide a synopsis of the work.

Members of the Core Content Work Group (name of organization): Matt Weaver (CareSpark); Jamel Sparkes (CareSpark); Mohammed Pervaiz (Delaware Health Information Network); Omar Bouhaddou (Veterans Administration); Marie Swall (Social Security Administration); Mike McCoy (Indiana University, Regenstrief Institute); Lonnie Blevins (Indiana University, Regenstrief Institute); Paul Fu (Long Beach Network for Health); Sumit Nagpal (Med Virginia); Gerard Filicko (Med Virginia); Geoff Lawson (North Carolina Healthcare Information and Communications Alliance); Dave Perry (Lovelace Clinic Foundation); Dave Handren (Lovelace Clinic Foundation); Mark Butler (Lovelace Clinic Foundation); Shirley Fuller (Lovelace Clinic Foundation); Ben Stein (New York eHealth Collaborative); Chris Clark (West Virginia Health Information Network); Mazhar Shaik (West Virginia Health Information Network); Carla Lachecki (Wright State University); Betty Sydelko (Wright State University); Mary Crimmins (Wright State University); Kim Mills (HealthLINC, Bloomington Hospital); Mike Sullivan (HealthLINC, Bloomington Hospital); Kim Seonho (Community Health Information Collaborative); John Fraser (Community Health Information Collaborative); George Peredy (Kaiser Permanente); Joseph Columna (Kaiser Permanente); Rodney Cain (HealthBridge); Marty Larson (HealthBridge); Albert Edward (Cleveland Clinic Foundation); Robert Lemon (Cleveland Clinic Foundation); Sidney Brown (Cleveland Clinic Foundation).

Liaisons from external organizations to the Core Content Work Group: Carol Bean (Office of the National Coordinator); Bob Yencha (Health Information Standards Technology Panel); Virginia Riehl (Certification Commission for Health Information Technology); Andrew McCaffrey (National Institute for Standards and Testing).

Subject matter experts from the Use Case Work Groups: Sandy McLeaf (EHR Lab Results); Shirley Fuller (Emergency Responder); Dave Perry (Emergency Responder); Benson Chang (Medication Management); Jane McKnight (Consumer Empowerment—Registration and Medication History); Richard Steen (Consumer Empowerment—Consumer Access to Clinical Information); Beth Hurter (Consumer Empowerment—Consumer Access to Clinical information); Matt Berlin (Biosurveillance); David Dobbs (Biosurveillance); Nicholas Soulakis (Biosurveillance); Jennifer Puyenbroek (Biosurveillance); Marty Prahl (Social Security Release of Information); Debbie Somers (Social Security Release of Information); Aditya Naik (Social Security Release of Information); Randy Barrows (Quality).

References

- 1.Brailer DJ. Interoperability: the key to the future health care system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;Suppl Web Exclusives:W5.19–5.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiell A, Forster AJ, Stiell IG, et al. Prevalence of information gaps in the emergency department and the effect on patient outcomes. CMAJ 2003;169:1023–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith PC, Araya-Guerra R, Bublitz C, et al. Missing clinical information during primary care visits. JAMA 2005;293:565–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shapiro JS, Kannry J, Kushniruk AW, et al. Emergency physicians' perceptions of health information exchange. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2007;14:700–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Walraven C, Taljaard M, Bell CM, et al. Information exchange among physicians caring for the same patient in the community. CMAJ 2008;179:1013–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammond WE. The making and adoption of health data standards. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1205–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halamka J, Overhage JM, Ricciardi L, et al. Exchanging health information: local distribution, national coordination. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:1170–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond CC, Shirky C. Health information technology: a few years of magical thinking? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:w383–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health and Human Services Fact Sheet The decade of information technology, a framework for strategic action. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2004pres/20040721.html (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 10.Health and Human Services Fact Sheet HHS awards contracts to advance nationwide interoperable health information technology. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2005pres/20051006a.html (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 11.Health and Human Services News Release HHS awards contracts to develop nationwide health information network. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2005pres/20051110.html (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 12.Gartner Group Summary of the NHIN prototype architecture contracts. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_10731_848093_0_0_18/summary_report_on_nhin_Prototype_architectures.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 13.Office of the National Coordinator Nationwide Health Information Network (NHIN): Trial Implementations. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=1191&parentname=CommunityPage&parentid=9&mode=2&in_hi_userid=10732&cached=true (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 14.Health Information Technology Standards Panel http://www.hitsp.org/ (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 15.HITSP Harmonization Framework http://www.hitsp.org/harmonization.aspx (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 16.Kuperman G, Blair J, Devaraj S, et al. NHIN core content specification for exchange of the summary patient record. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_10731_848155_0_0_18/FINAL%202008%20NHIN%20Coop%20Specification%20for%20Exchange%20of%20the%20Summary%20Patient%20Record%20–%20Final.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 17.Office of the National Coordinator Emergency responder electronic health record: detailed use case. 20 December 2006. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_10741_848104_0_0_18/EmergencyRespEHRUseCase.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 18.HITSP web site Emergency responder electronic health record interoperability specification. http://hitsp.org/InteroperabilitySet_Details.aspx?MasterIS=true&InteroperabilityId=51&PrefixAlpha=1&APrefix=IS&PrefixNumeric=04 (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 19.HITSP web site C32-HITSP summary documents using HL7 continuity of care document (CCD) component. http://www.hitsp.org/ConstructSet_Details.aspx?&PrefixAlpha=4&PrefixNumeric=32 (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 20.HL7 Press Release HL7 continuity of care document, a healthcare IT interoperability standard, is approved by balloting process and endorsed by healthcare IT standards panel. February 12, 2007. http://www.hl7.org/documentcenter/public/pressreleases/20070212.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 21.Dolin RH, Alschuler L, Boyer S, et al. HL7 clinical document architecture, release 2. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006;13:30–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ONC web site NHIN Trial Implementation summary record content data specifications. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=18&objID=848359&parentname=CommunityPage&parentid=95&mode=2&in_hi_userid=10731&cached=true (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 23.HIMSS Electronic Health Record Association Continuity of care document (CCD) quick start guide. http://www.himssehra.org/ASP/CCD_QSG_20071112.asp (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 24.National Institute of Standards and Technology CDA guideline validation. http://xreg2.nist.gov/cda-validation/index.html#downloads.html (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 25.Integrating the Healthcare Enterprise (IHE) Laboratory technical framework, Rev. 2.1. August 8, 2008. http://www.ihe.net/Technical_Framework/upload/ihe_lab_TF_rel2_1-Vol-3_FT_2008-08-08.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 26.HITSP web site Biosurveillance interoperability specification. http://www.hitsp.org/InteroperabilitySet_Details.aspx?MasterIS=true&InteroperabilityId=49&PrefixAlpha=1&APrefix=IS&PrefixNumeric=02 (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 27.HITSP, presentation at HIMSS about biosurveillance use case. 7/29/2007. http://www.himss.org/content/files/HITSP/HITSPCCHIT-IS02.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009), slides 29–35.

- 28.NHIN Trial Implementations Biosurveillance use case requirements document. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/gateway/PTARGS_0_10731_848167_0_0_18/Biosurveillance_Use_Case_v1.0%20%20043008.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 29.HITSP web site Quality interoperability specification. http://www.hitsp.org/InteroperabilitySet_Details.aspx?MasterIS=true&InteroperabilityId=53&PrefixAlpha=1&APrefix=IS&PrefixNumeric=06 (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 30.American Medical Association Collaborative for performance measure integration with EHR systems. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/clinical-practice-improvement/clinical-quality/collaborative-performance-measure-integration-ehr-systems.shtml (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 31.Alliance for Pediatric Quality Quality reporting document architecture (QRDA) initiative phase I final report. http://www.alschulerassociates.com/library/documents/QRDA_Phase_I_Public_Report.pdf (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 32.Health and Human Services Press Release Nationwide Health Information Network advances: foundation for interoperable health information exchange established—path to nationwide production set. http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2008pres/12/20081219a.html (accessed 9 September 2009).

- 33.Health and Human Services Fact Sheet Nationwide Health Information Network (NHIN): limited production. http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=1192&parentname=CommunityPage&parentid=2&mode=2&in_hi_userid=10741&cached=true (accessed 9 September 2009).

- 34.Social Security News Release Social security to fund $24 million in contracts for electronic medical records. http://www.ssa.gov/pressoffice/pr/electronic-med-records-pr.htm (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 35.Interoperability Showcase HIMSS Conference. http://www.interoperabilityshowcase.org/himss09/index.asp (accessed 20 September 2009).

- 36.National Institute of Standards and Technology Manufacturing systems integration division XML test bed. http://www.mel.nist.gov/msid/XML_testbed/related_links.html (accessed 20 September 2009).