Abstract

Mycobacterium celatum is a nontuberculous mycobacterium that rarely causes pulmonary disease in immunocompetent subjects. We describe the successful treatment of M. celatum lung disease with antimicobacterial chemotherapy and combined pulmonary resection. A 33-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with a 3-month history of a productive cough. Her medical history included pulmonary tuberculosis 14 years earlier. Her chest X-ray revealed a large cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe. The sputum smear was positive for acid-fast bacilli, and M. celatum was subsequently identified in more than three sputum cultures, using molecular methods. After 1 year of therapy with clarithromycin, ethambutol, and ciprofloxacin, the patient underwent a pulmonary resection for a persistent cavitary lesion. The patient was considered cured after receiving 12 months of postoperative antimycobacterial chemotherapy. There has been no recurrence of disease for 18 months after treatment completion. In summary, M. celatum is an infrequent cause of potentially treatable pulmonary disease in immunocompetent subjects. Patients with M. celatum pulmonary disease who can tolerate resectional surgery might be considered for surgery, especially in cases of persistent cavitary lesions despite antimycobacterial chemotherapy.

Keywords: Nontuberculous mycobacteria, Mycobacterium celatum, lung disease, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are ubiquitous organisms that are increasingly recognized as important causes of chronic pulmonary infection in non-immunocompromised individuals.1 Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and Mycobacterium abscessus constitute the most commonly encountered causes of NTM lung disease in Korea,2 and several other NTM have been identified as pathogens.3,4

Mycobacterium celatum was first described in 1993 as a new species with a mycolic acid pattern that closely resembled Mycobacterium xenopi (xenopi-like), although it was biochemically indistinguishable from MAC.5 M. celatum is an uncommon cause of human infection, with an invasive disease occurring primarily in the form of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients.6 There are only a few case reports of M. celatum lung disease in immunocompetent patients.7-9 To date, only one case of M. celatum lung disease has been reported in Korea.10 However, this patient was given first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs and the treatment outcome is unknown.

We report an immunocompetent adult patient with M. celatum lung disease who was successfully treated with a pulmonary resection in combination with antimycobacterial chemotherapy with clarithromycin, ethambutol, and ciprofloxacin.

CASE REPORT

A 35-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for further examination and management of probable NTM lung disease. The patient's medical history included a pulmonary tuberculosis episode when she was 21 years old. She lived in an urban area and had no history of smoking, alcoholism, or use of immunosuppressive drugs.

Four months before her visit to our hospital, the patient reported a three-month history of a productive cough. A chest radiograph revealed a large cavity in the left upper lobe. The patient was initially diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis and received isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide. Two months later, NTM were cultured from her sputum, and the colonies were identified as M. celatum. She was referred to our hospital for probable NTM lung disease.

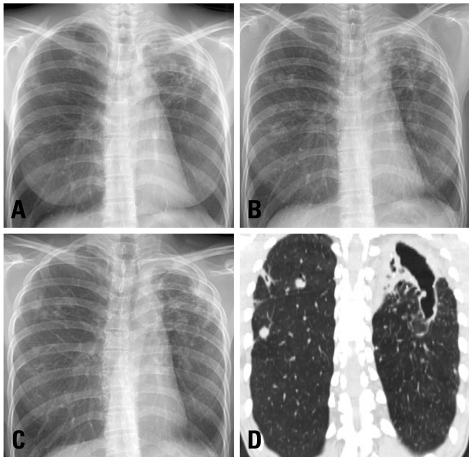

Physical examination upon presentation showed that the patient was 162 cm tall and weighed 44 kg. The results of the clinical laboratory tests were unremarkable, apart from a moderately elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (69 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (0.69 mg/dL). A human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative. A chest radiography revealed a large cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe and multiple nodular opacities that involved the right lung (Fig. 1A), which appeared to improve slightly after 4 months of treatment with anti-tuberculosis drugs. Her sputum was positive in acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining, and numerous mycobacterial colonies were cultured from three sputum specimens at our hospital. All of these colonies were subsequently identified as M. celatum. This identification was confirmed using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-restriction fragment length polymorphism method, based on the rpoB gene.11 Although the patient was recommended for a further work-up and a change of drug regimen, she was lost from follow-up.

Fig. 1.

A 35 year-old woman with Mycobacterium celatum lung disease. (A) The posteroanterior chest radiography at first visit shows a large cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe. Note the multiple nodular opacities involving the right lung. (B) The chest radiography at the subsequent revisit shows aggravation of the cavitation in the left upper lobe, as well as enlargement of the nodular lesions in the right lung. (C) The chest radiography taken after 12 months of antibiotic treatment shows that the size of the cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe is unchanged, although the multiple nodular lesions in the right lung have improved. (D) The chest computed tomography scan taken after 12 months of antibiotic treatment reveals a large remnant cavitary lesion that involves both the left upper lobe and the superior segment of the left lower lobe.

Twenty-two months later, the patient revisited our hospital due to a persistent productive cough. A chest radiography showed aggravation of the cavitation in the left upper lobe, as well as enlargement of the nodular lesions in the right lung (Fig. 1B). The smears of two sputum specimens were positive for AFB, and yielded M. celatum. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed at the Korean Institute of Tuberculosis. The isolate was found to be susceptible to clarithromycin [minimal inhibition concentration (MIC), 1 µg/mL] and ciprofloxacin (MIC, 0.25 µg/mL) using the broth microdilution method according to the guidelines set forth by the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS).12 In addition, using the absolute concentration method on the Lowenstein-Jensen medium, the isolate was shown to be susceptible to ethambutol (critical concentration, 2 µg/mL), streptomycin (critical concentration, 10 µg/mL), and kanamycin (critical concentration, 40 µg/mL), but resistant to isoniazid (critical concentration, 0.2 µg/mL) and rifampin (critical concentration, 40 µg/mL). Combination antimycobacterial chemotherapy, which included clarithromycin (1,000 mg/day), ethambutol (800 mg/day), and ciprofloxacin (1,000 mg/day), was initiated. Conversion to negative sputum cultures was achieved in 3 months.

Despite 12 months of antimycobacterial chemotherapy, the patient suffered from persistent sputum production. A chest radiography revealed that the size of the cavitary lesion in the left upper lobe was unchanged, although the multiple nodular lesions in the right lung had improved (Fig. 1C). Chest computed tomography revealed a large remnant cavitary lesion that involved both the left upper lobe and the superior segment of the left lower lobe (Fig. 1D). This cavitary lesion was considered to have a high possibility of relapse. Therefore, the patient underwent a left upper lobectomy and superior segmentectomy of the left lower lobe. The microscopic findings were parenchymal destruction with cavity and chronic granulomatous inflammation with caseous necrosis. The tissue culture was not requested during the surgery. The patient was considered cured after receiving 12 months of postoperative antimycobacterial chemotherapy. There has been no recurrence of disease 18 months after treatment completion.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of M. celatum lung disease being successfully treated with antimycobacterial chemotherapy in combination with pulmonary resection in Korea. In this case, M. celatum was clearly shown to be the etiologic agent of the cavitary lesion of the left lung. Considering the clinical and radiographic features, in addition to the repeated isolation of M. celatum, the diagnostic criteria for NTM lung disease were fulfilled.1

The clinical outcome for many M. celatum-infected patients is poor, probably due to their profound immunosuppression. The previously reported immunocompetent patients with pulmonary infection were assigned different treatment regimens with combinations of antimycobacterial agents, mainly ethambutol and clarithromycin.7-9 Clinical improvement was obtained within 6 months of the initiation of therapy in two out of three patients. One patient who received anti-mycobacterial therapy died 6 weeks after starting therapy from complications that were apparently related to the M. celatum infection.7

The susceptibility test profiles of the previously reported cases showed variability.5-9 The organism was generally found to be susceptible to clarithromycin and ciprofloxacin, with ciprofloxacin resistance being reported infrequently.13-15 All the reported isolates were resistant to rifampin and most were resistant to isoniazid. In an animal model of M. celatum infection, clarithromycin, azithromycin, and ethambutol were shown to be the most active agents.16 Susceptibility testing is advisable in order to guide treatment choices. Based on the recommended treatment regimens and the results of in vitro susceptibility testing, we selected a combination of ethambutol, clarithromycin, and ciprofloxacin for our patient. However, organisms such as M. celatum have limited in vitro susceptibility, with limited evidence for a correlation between in vitro susceptibility and clinical response in the treatment of M. celatum pulmonary disease.1

In summary, M. celatum is an infrequent cause of potentially treatable pulmonary disease in immunocompetent subjects. Patients with M. celatum lung disease who can tolerate resectional surgery might be considered for surgery, especially in cases of persistent cavitary lesions despite antimycobacterial chemotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (R11-2002-103).

Footnotes

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Jeon K, Kim TS, Lee KS, Park YK, et al. Clinical significance of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from respiratory specimens in Korea. Chest. 2006;129:341–348. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.2.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park HY, Koh WJ, Kwon OJ, Lee NY, Shim YM, Park YK, et al. Pulmonary disease caused by Mycobacterium xenopi: the first case in Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:871–875. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.5.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park S, Suh GY, Chung MP, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Lee KS, et al. Clinical significance of Mycobacterium fortuitum isolated from respiratory specimens. Respir Med. 2008;102:437–442. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler WR, O'Connor SP, Yakrus MA, Smithwick RW, Plikaytis BB, Moss CW, et al. Mycobacterium celatum sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:539–548. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-3-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiansen DC, Roberts GD, Patel R. Mycobacterium celatum, an emerging pathogen and cause of false positive amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;49:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bux-Gewehr I, Hagen HP, Rüsch-Gerdes S, Feurle GE. Fatal pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium celatum in an apparently immunocompetent patient. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:587–588. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.587-588.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tjhie JH, van Belle AF, Dessens-Kroon M, van Soolingen D. Misidentification and diagnostic delay caused by a false-positive amplified Mycobacterium tuberculosis direct test in an immunocompetent patient with a Mycobacterium celatum infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2311–2312. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2311-2312.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piersimoni C, Zitti PG, Nista D, Bornigia S. Mycobacterium celatum pulmonary infection in the immunocompetent: case report and review. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:399–402. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DK, Kim BJ, Kook YH, Lee CT, Yoo CG, Kim YW, et al. Pulmonary infection with Mycobacterium celatum in immunocompetent host: The first case report in Korea. Tuberc Respir Dis. 1999;47:697–703. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H, Park HJ, Cho SN, Bai GH, Kim SJ. Species identification of mycobacteria by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism of the rpoB gene. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2966–2971. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.8.2966-2971.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes; Approved Standard. Wayne, PA: NCCLS; 2003. Document No. M24-A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bull TJ, Shanson DC, Archard LC, Yates MD, Hamid ME, Minnikin DE. A new group (type 3) of Mycobacterium celatum isolated from AIDS patients in the London area. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:861–862. doi: 10.1099/00207713-45-4-861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Emler S, Praplan P, Rohner P, Auckenthaler R, Hirschel B. Disseminated infection with Mycobacterium celatum. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1996;126:1062–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zurawski CA, Cage GD, Rimland D, Blumberg HM. Pneumonia and bacteremia due to Mycobacterium celatum masquerading as Mycobacterium xenopi in patients with AIDS: an underdiagnosed problem? Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:140–143. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.2.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fattorini L, Baldassarri L, Li YJ, Ammendolia MG, Fan Y, Recchia S, et al. Virulence and drug susceptibility of Mycobacterium celatum. Microbiology. 2000;146:2733–2742. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-11-2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]