Abstract

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) also known as post infectious encephalomyelitis is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that typically presents as a monophasic disorder associated with multifocal neurological symptoms and disability. It may follow vaccination in children or infection. Viral infection like measles, rubella, influenza, Epstein bar, HIV, herpes, cytomegalusvirus (CMV) and West Nile virus have been implicated in the causation. Among bacteria, group A hemolytic streptococcus, mycoplasma pneumonia, Chlamydia, Rickettesia and leptospira have been shown to cause ADEM. There are few reports of ADEM due to tuberculosis (TB). We describe acute disseminated encephalomyelitis due to tuberculosis in a 35 year old female who initially started with neuropsychiatric manifestations and later developed florid neurological deficit and classical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) lesions suggestive of the disease. The patient recovered completely after antitubercular therapy and is following our clinic for the last 12 months now.

Keywords: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, tuberculosis

Abstract

Die akute disseminierte Enzephalomyelitis (ADEM), auch postinfektiöse Enzephalomyelitis genannt, ist eine demyelisierende Erkrankung des Zentralnervensystems (ZNS). Sie hat einen monophasischen Verlauf mit multifokalen neurologischen Symptomen und Ausfällen. Sie kann als Folge von Schutzimpfungen bei Kindern oder Infektionen auftreten. Virusinfektionen mit Masern, Röteln, Influenza, Eppstein-Bar, HIV, Herpes, Zytomegalie-Virus (CMV) und West-Nil-Virus wurden als Auslöser beobachtet.

Unter den Bakterien waren es die Gruppe der hämolytischen Streptokokken, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydien, Rickettsien und Leptospiren, die eine aktue disseminierte Enzephalomyelitis verursachen können.

Es gibt wenige Berichte von ADEM bei Tuberkulose. Wir berichten über eine ADEM bei Tuberkulose einer 35-jährigen Frau, die anfangs wegen neuropsychiatrischen Beschwerden behandelt wurde und später floride neurologische Ausfälle und klassische Läsionen in der Magnetresonanztomographie aufwies. Die Patientin erholte sich nach einer tuberkulostatischen Therapie und steht seit 12 Monaten unter klinischer Beobachtung.

Introduction

CNS tuberculosis accounts for about one percent of all cases of TB and six percent of all extrapulmonary infections in immunocompetent individuals [1]. Rarely CNS tuberculosis presents as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, an uncommon inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system. It results from a transient autoimmune response towards myelin or other self antigens possibly via molecular mimicry or by non-specific activation of auto-reactive clones [2]. The mechanism of ADEM is not completely understood. It has been proposed that peptides from microbial proteins that have sufficient structural similarity with the hosts self peptides can activate T-lymphocytes. T-lymphocytes when activated infiltrate the central nervous system and result in additional mono-nuclear cells to cross the blood brain barrier, leading to inflammation and demyelination [3]. Sensitivity to tubercular protein has been proposed to be a mechanism in causation of ADEM due to tuberculosis.

Case description

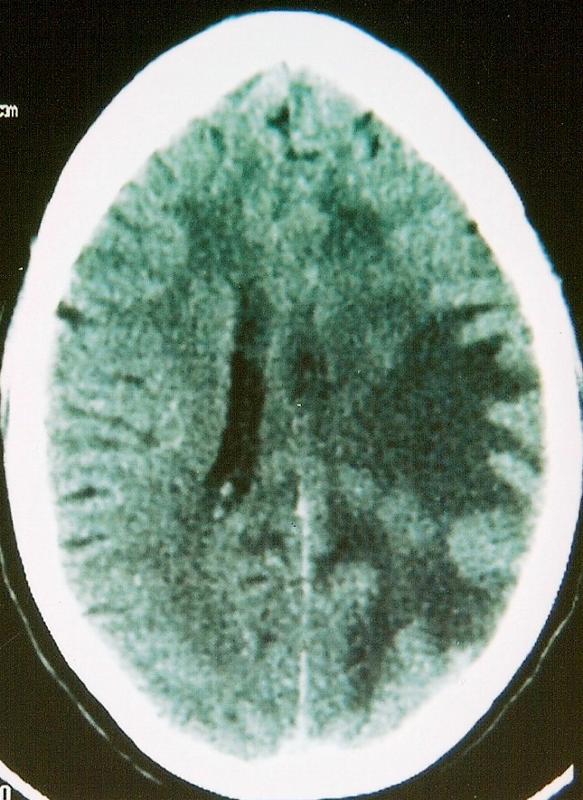

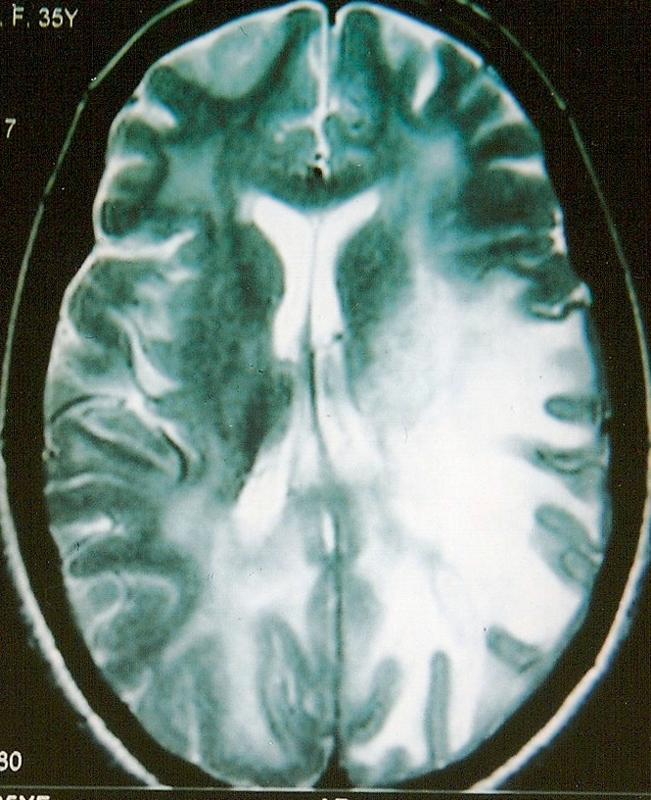

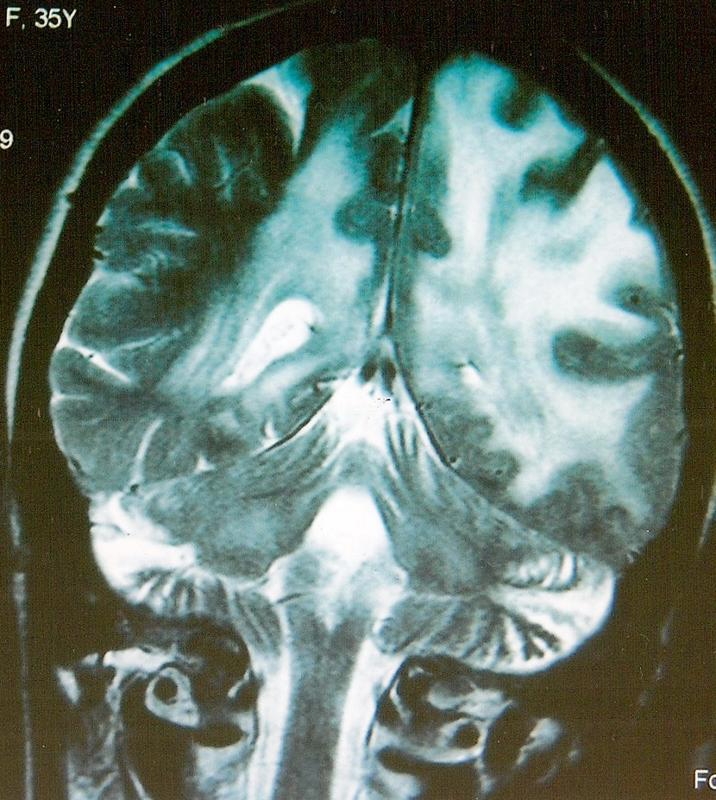

A 35 year old Kashmiri female had presented with history of increased talkativeness, quarrelsome attitude, forgetfulness, poor recognition of close relations, social withdrawal, aimless wandering of 3 weeks duration to a local psychiatrist. She had no relief in her symptoms on psychiatric treatment. She was brought to medical emergency room of Govt. S.M.H.S Hospital Srinagar, an associated hospital of the Govt. Medical College Srinagar, Kashmir, when her husband noticed weakness of the right side of the body with deviation of face to one side of 3 days duration. Soon after admission in the emergency room she became drowsy and had incontinence of urine without any convulsions. There was no history of fever or rash, or bleeding from any site. She was nondiabetic with no significant medical history in the past. On examination the patient was drowsy but arousable, however she was not oriented to time, place or person. She had no jaundice or lymphadenopathy. Her systemic examination was normal. The neurological examination revealed positive neck stiffness, right facial palsy and right hemiplegia. Her right side plantar was upgoing. She had right side papilloedema on fundoscopic examination. On evaluation she was found to have leukocytosis (11200) with high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (60 min first hour). Her liver and renal function tests, serum calcium and phosphorous were normal. ECG and x-ray chest revealed no abnormality. HIV serology was negative. CT scan of the head revealed white matter edema of the left parieto-occipital region with mass effect on the left ventricle with midline shift suggestive of venous thrombosis. Contrast CT of the head showed enhancement of these lesions suggestive of demyelination (Figure 1 (Fig. 1)). Contrast MRI of the brain showed extensive vasogenic edema in periventricular white matter, predominantly in the left parieto-occipital region with hyperintense signal in ventral pons and cerebral peduncle (along the descending tracts) with enlarged left cerebral peduncles with mass effect on the left lateral ventricle suggestive of a tumefactive demyelination (Figure 2 (Fig. 2)). She was given decongestive therapy with intravenous Mannitol and lumbar puncture was done very carefully. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed a total leucocyte count of 210 cells with 85% lymphocytes, 15% neutrophils, CSF proteins 542 mg/dl, sugar 28 mg/dl, adenosine deaminase (ADA) levels were 27 IU (normal <10), Gram stain and India ink were negative, acid-fast bacteria (AFB) stain was negative. TB polymerase chainreaction (PCR) was positive, venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) was negative, CSF culture for mycobacterium tuberculosis was positive. On the basis of these findings a 4-drug regimen of antitubercular treatment (ATT) (Tab. INH 300 mg, Cap. Rifampcin 600 mg, Tab. Ethambutol 800 mg, Tab. Pyrazinamide 1.5 g and Tab. Pyridoxine 60 mg) was started. She was given Inj. Methylprednisolone 1 g I/V once daily for 5 days followed by oral steroids (Tab. Prednisolone 40 mg daily). Oral steroids were tapered over the next four weeks and ATT was continued. The patient had progressive improvement in 4 weeks time. On discharge she was conscious, oriented to time place and person and had power of grade V in all four limbs. Repeat CT done after 4 weeks showed marked regression of edema and repeat MRI done after three months of ATT showed few post ADEM residual demyelinating lesions (Figure 3 (Fig. 3)). The patient is fine now and is following our clinic for the last one year now.

Figure 1. Contrast CT Scan Head.

Figure 2. MRI before treatment.

Figure 3. MRI after treatment.

Discussion

The typical cases of ADEM syndrome develop 6 days to 6 weeks following an infectious illness usually due to viruses. The index case had MRI features of ADEM and her CSF was suggestive of tuberculosis, a rare cause of the syndrome. She had complete recovery following antitubercular treatment. There is limited data available in the English literature regarding tuberculosis as a cause of ADEM. Mustafa et al. [4] described the clinical profile of a 50 year old male with pulmonary tuberculosis who developed headache, diplopia, and unsteadiness of gait and had MRI features of ADEM after the 10th day on antitubercular treatment. Their patient had dramatic response to pulse steroid therapy with complete recovery on antitubercular treatment, as in the index case. This implies that patient with tuberculosis can develop ADEM even during treatment. Udani et al. [5] described series of 30 cases of tubercular encephalopathy with and without meningitis in 1970 (pre MRI era). In their series main clinical features were impaired consciousness, paralysis and decerebrate postures. They described diffuse or patchy myelin loss in the white matter, occasional hemorrhage and glial nodules with moderate changes in the grey matter. They postulated sensitivity to tuberculoprotein or to brain itself as the cause of neurological manifestation of tuberculosis. Most of the patients in their series had evidence of tuberculosis in the form of miliary tuberculosis, abdominal tuberculosis, and pulmonary tuberculosis in addition to CNS involvement. CSF acid fast bacilli were seen in only one case in their series. The index case had isolated central nervous system involvement (ADEM) with no pulmonary or abdominal tuberculosis. She had no tuberculomas in the brain and her CSF acid fast bacilli test was negative. Tuberculosis as a rarer cause of ADEM is further emphasized by a series of 45 ADEM cases described by Maramattom et al. [6] over a period of 8 years in two teaching hospitals of South Indian state of Kerala. Authors observed that the clinical presentation was similar to that described earlier in the literature. The predominant clinical features in their case series were motor and cranial nerve manifestations, minimal fever or meningism, a strong association with antecedent infections and dramatic changes on MR imaging. None of the patients in their series had tuberculosis as the antecedent illness. In another recent series of 61 patients of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis over a period of five years, Paniker et al. [7] observed that a majority of the patients had a nonspecific febrile illness prior to ADEM and again none of their patients had tuberculosis. Tuberculosis should be considered as a cause for ADEM particularly in countries where it is rampant, of course AIDS epidemic has spared no country now. In any classical ADEM case CSF is usually abnormal in more than 67% cases. CSF shows a moderate pleocytosis with increased protein content [7]. There is lymphocytic predominance both in ADEM and tuberculosis so the CSF picture can be confusing. This reflects that in high suspicious cases ADA levels, TB PCR and TB culture should be routinely ordered to rule out tuberculosis as a cause of ADEM. Our index case had positive TB PCR and positive CSF culture; in addition she had high ADA levels which clinched the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Differential diagnosis of ADEM includes multiple sclerosis, infectious meningoencephalitis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, primary isolated CNS angitis, vasculitis and CNS metastasis and neurosarcoidosis. Classical lesions on MRI and temporal profile are diagnostic. Treatment options include I/V steroids (methylprednisolone 1g I/V for 5 days), I/V immunoglobulins and plasmapharesis. The natural history of ADEM in general is variable. Patients often panic once the symptoms transiently recur. This should not be confused with a relapse, which refers to worsening of clinical condition or of new deficits lasting longer than 24 hours. Data from Asian countries have show that the rate of progression to multiple sclerosis is low [7], in contrast to Western population where the rate is higher due to unknown reasons [8]. Our patient had complete recovery, most of the adults in different series were left with residual degrees of disability after ADEM [7]. Mortality rates of up to 20% have been reported which depend upon the level of consciousness on presentation, co-morbidities and extension of lesions. Children have better prognosis than adults.

We conclude that although tuberculosis is a rarer cause of ADEM, the emergence of multi drug resistant tuberculosis due to AIDS epidemic [9] must be kept in view. Even in the developed world, clinicians must keep this uncommon manifestation of a common disease in mind while evaluating a patient with altered behaviour and monophasic illness suggestive of ADEM.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2004. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stüve O, Zamvil SS. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Curr Opin Neurol. 1999;12(4):395–401. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199908000-00005. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00019052-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sriram S, Steinman L. Postinfectious and postvaccinial encephalomyelitis. Neurol Clin. 1984;2(2):341–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ozham M, Tiryaki Aydogen O, Kumral E. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following pulmonary tuberculosis. Turkish Respir J. 2005;6(3):161–163. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Udani PM, Dastur DK. Tuberculous encephalopathy with and without meningitis. Clinical features and pathological correlations. J Neurol Sci. 1970;10(6):541–561. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(70)90187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Maramattom BV, Sarada C. Clinical features and outcome of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM): An outlook from South India. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2006;9(1):20–24. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.22817. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.22817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Panicker JN, Nagaraja D, Kovoor JM, Subbakrishna DK. Descriptive study of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and evaluation of functional outcome predictors. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56(1):12–16. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.62425. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0022-3859.62425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwarz S, Mohr A, Knauth M, Wildemann B, Storch-Hagenlocher B. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: a follow-up study of 40 adult patients. Neurology. 2001;56(10):1313–1318. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.10.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Braun MM, Byers RH, Heyward WL, Ciesielski CA, Bloch AB, Berkelman RL, Snider DE. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(9):1913–1916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]