Abstract

Background

Various mechanisms of atrial fibrillation (AF) have been demonstrated experimentally. Invasive methods to study these mechanisms in humans have limitations, precluding continuous mapping of both atria with sufficient resolution. In this paper, we present continuous biatrial epicardial activation sequences of AF in humans, using noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI).

Methods and Results

In testing phase, ECGI accuracy was evaluated by comparing ECGI with co-registered CARTO images during atrial pacing in six patients. Additionally, correlative observations from catheter mapping and ablation were compared with ECGI in three patients. In study phase, ECGI maps during AF in twenty-six patients were analyzed for mechanisms and complexity.

ECGI noninvasively imaged the low-amplitude signals of AF in a wide range of patients (97% procedural success). Spatial accuracy for determining initiation sites from pacing was 6mm. Locations critical to maintenance of AF identified during catheter ablation were identified by ECGI; ablation near these sites restored sinus rhythm. In the study phase, the most common patterns of AF were multiple wavelets (92%), with pulmonary vein (69%) and non-pulmonary vein (62%) focal sites. Rotor activity was seen rarely (15%). AF complexity increased with longer clinical history of AF, though the degree of complexity of non-paroxysmal AF varied widely.

Conclusions

ECGI offers a noninvasive way to map epicardial activation patterns of AF in a patient-specific manner. The results highlight the coexistence of a variety of mechanisms and variable complexity among patients. Overall, complexity generally increased with duration of AF.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, arrhythmia (mechanisms), electrophysiology mapping, noninvasive imaging, ECGI

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, accountable for frequent hospitalizations and increased risks of stroke, heart failure, and mortality.1,2 Published guidelines classify patients into groups based on the clinical duration and behavior of AF (paroxysmal, persistent, long-standing persistent, permanent)3. While this approach has served clinicians well, it does not take into account mechanisms of the arrhythmia.

Mechanisms of initiation and perpetuation of AF continue to be the subject of ongoing intense investigation.4–8 Proposed mechanisms include “multiple wavelet,”9 “mother rotor/fibrillatory conduction”10, and “pulmonary vein/focal source.”11 Contributions from the autonomic nervous system play a role in AF as well.12

Toward improving the treatment of AF, it is incumbent to understand the underlying mechanism in each individual patient. The HRS/EHRA/ECAS 2007 Expert Consensus Statement on the Surgical and Catheter Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation summarizes the state of knowledge: “Although much has been learned about the mechanisms of AF, they remain incompletely understood. Because of this, it is not possible to precisely tailor an ablation strategy to a particular AF mechanism.”13 Currently, there is a paucity of simultaneous biatrial mapping data during AF in humans. In this paper, we present simultaneous biatrial epicardial activation sequences during AF for a wide range of AF phenotypes. Maps were obtained using noninvasive Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI)14,15 and analyzed in terms of mechanisms and complexity of activation patterns.

Methods

Thirty-six subjects included in this study had a history of AF and were referred from Washington University electrophysiology and cardiothoracic surgery services. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

ECGI System

ECGI methodology was described previously in detail14,15. 256 carbon electrodes were applied to the patient's torso surface and connected to a portable mapping system. CT markers were attached to each electrode. After electrode application, patients underwent thoracic noncontrast gated CT imaging with axial resolution of 3mm. Scans were gated at 20% of the R-R interval (atrial diastole) if in sinus rhythm. If patients undergo repeat ECGI over time, the electrode strips are placed in the same location, and an additional CT scan is not needed. Atrial epicardial surface geometry and body surface electrode positions were labeled and digitized from CT images.

The 256 channels of body surface potentials (BSP) were sampled at 1-ms intervals. During catheter EP study, BSP were acquired during atrial pacing from various locations and during AF. Several minutes of data were recorded from each patient. T-Q segments were used for analysis of AF.

The BSP and geometrical information (torso-heart geometrical relationship) were combined by ECGI algorithms to noninvasively construct epicardial potential maps, electrograms, activation sequences (isochrones) and repolarization patterns. Activation movies for several consecutive beats were constructed by animating the activation wave front on the patient-specific CT-derived epicardial surface.

ECGI has been validated extensively (see Online Supplement for relevant references). In the atria, it has been used to map sinus rhythm activation14,15 and repolarization16 with similar findings to invasive mapping of Durrer.17 Atrial reentry and focal mechanisms have been demonstrated with ECGI imaging of isthmus dependent right atrial flutter,14 focal left atrial tachycardia,18 and incomplete pulmonary vein isolation,19 all validated during endocardial mapping and ablation. Also, ECGI mapping of scar-related atypical left atrial flutter was validated during surgical mapping20. ECGI maps the entire epicardium during a single beat. Unlike catheter mapping, it does not require accumulating data from many beats to complete a map, nor does it require signal averaging from multiple beats. It can record continuously and capture the dynamics of electrical excitation.

TESTING PHASE

Simulation of Focal Atrial Activation with Pacing during Biatrial ECGI Mapping

Previous studies have reported the accuracy of ECGI for predicting ventricular pacing sites to be 2–10mm21. Because of complex atrial anatomy and various known locations of AF triggers, ECGI was performed on six patients undergoing PVI during pacing from various known sites of AF initiation (testing phase). Locations of pacing sites were recorded onto electroanatomic maps (CARTO, Biosense-Webster) and the paced anatomical structure (e.g. specific pulmonary vein) was identified. ECGI maps were analyzed to determine the pacing site location based on earliest activation, location of a potential minimum during early depolarization and a corresponding potential maximum during repolarization (Figure 1). When possible, the distance between the ECGI-imaged site and the site on the catheter electroanatomic map was measured (using Amira 4.1, Visage Imaging).

Figure 1. ECGI accuracy locating atrial initiation sites, simulated by pacing.

TOP LEFT: Isochrone map of LA (anterior view) with white star indicating earliest activation imaged by ECGI. BOTTOM LEFT: Potential map of LA locating the minimum of earliest activation (blue region, white star). TOP RIGHT: Merged 3-D CARTO and ECGI LA images (anterior view). Pacing sites in RSPV, atrial septum, and anterior mitral valve annulus are shown from CARTO (green circles) and ECGI (yellow diamonds). BOTTOM RIGHT: Detailed information regarding pacing sites and distance between CARTO and ECGI-imaged locations. RSPV=Right Superior Pulmonary Vein; RIPV=Right Inferior Pulmonary Vein; LAA=Left Atrial Appendage; MV=Mitral Valve.

Correlation of Simultaneous Invasive Catheter Mapping with Noninvasive ECGI during AF

Of the 6 patients who underwent ECGI during the testing phase, three developed AF during the EP procedure. Catheter mapping findings during AF were recorded, including locations of high-frequency activation and location of ablation that terminated AF, and compared to simultaneous ECGI activation movies.

STUDY PHASE

Analysis of Atrial Fibrillation

Activation movies were constructed during long RR intervals (300 to 1000ms) for the 26 patients who were ECGI imaged during AF. Visual analysis of at least 5 movies for each patient was performed. A wavelet was defined as a contiguous area of epicardial activation that was observed over minimum 5ms. Wavelet propagation was observed each millisecond, and the number of simultaneous wavelets was recorded every 5ms throughout the movie. The mean number of simultaneous wavelets participating in AF (“number of wavelets”) was recorded. The locations and number of epicardial activation sites that initiated new wavefronts (“number of focal sites”) were recorded. These focal sites may be spontaneous depolarization, microreentry, or epicardial breakthrough of an intramural wavefront. ECGI lacks the ability to discern these mechanisms. To avoid nonphysiologic error, the definition of focal site required the absence of local activity for 50ms before the focal site, and the site had to be observed at least twice in a movie segment. To quantify the complexity of an individual patient's AF, a “Complexity Index” was calculated as the sum of the number of wavelets and the number of focal sites. A Complexity Index of 1 represents the simplest AF, with higher numbers representing more complex AF.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were analyzed using a Student's t-test. When patients were grouped according to their clinical history (paroxysmal, persistent, long-standing persistent), analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to determine differences between the three groups. Tests for homogeneity of variance were performed within each group, and none were significant (< 0.05).

Patient Selection

Clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and Online Table 1. Twenty-six of the 36 patients were ECGI-imaged during AF and were included in AF analysis. Seven patients were ECGI-imaged during sinus rhythm alone, and 3 patients were ECGI-imaged in sinus rhythm during invasive mapping with atrial pacing. These 10 patients were excluded from AF analysis. Eleven patients were classified as paroxysmal (31%), nineteen as persistent (53%), and six as long-standing persistent (16%). The study population was heterogeneous with respect to age (31 to 76 years), duration of AF (1 month to 30 years), and left atrial size (3.5 to 5.7 cm).

Table 1.

| Number (%) | Mean (Range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.4 years (31–76 years) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 24 (67%) | |

| Female | 12 (33%) | |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 33 (91%) | |

| Black | 2 (6%) | |

| Other | 1 (3%) | |

| Years since diagnosis of AF | 8.3 years (0.2 to 30 years) | |

| Clinical classification of AF | ||

| Paroxysmal | 11 (31%) | |

| Persistent | 19 (53%) | |

| Longstanding Persistent | 6 (17%) | |

| Clinical History | ||

| Heart Failure | 2 (6%) | |

| Hypertension | 14 (39%) | |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2 (6%) | |

| Cerebrovascular Accident | 4 (11%) | |

| Left Atrial Dimension | 4.4 cm (3.5 to 5.7 cm) | |

| Mitral Regurgitation | 0.86 (0[none] to 3[severe]) | |

| Family History of AF | 6 (17%) | |

| Antiarrhythmic Medication | 36 (100%) | |

| Procedural History | ||

| Prior PVI | 7 (19%) | |

| Prior Maze | 2 (6%) | |

| Prior Fontan | 1 (3%) |

ECGI generated high-quality images in 35 of 36 patients (97%). The one patient without successful ECGI had undergone a prior Cox maze procedure22 and mitral valve replacement. She did not have a discernable atrial electrogram on 12-lead ECG. In all patients, ECGI was well-tolerated without any adverse events.

Results

TESTING PHASE

Simulation of Focal Atrial Activation with Pacing

During testing phase, ECGI was performed on 6 patients during PVI procedures with pacing from various atrial locations. A total of 37 paced events were recorded in all four pulmonary veins (PV), posterior left atrium, mitral isthmus and annulus, coronary sinus, atrial septum, sinus node and atrial appendages. The cardiac structure being paced was correctly identified by ECGI in all 37 pacing events (100% accuracy). Relative to electroanatomic maps, ECGI-determined pacing locations were accurate within 6.3±3.9mm (Figure 1).

Correlation of Simultaneous Invasive Catheter Mapping with Noninvasive ECGI during AF

Three patients had AF during PVI procedures allowing for simultaneous catheter mapping and ECGI imaging.

One patient demonstrated an intermittent driver in the RIPV during catheter mapping. AF terminated with ablation in the inferior-posterior left atrium (LA). ECGI immediately prior to this ablation lesion (Figure 2) repeatedly demonstrated: 1) RIPV focal site; 2) LA posterior wall focal site; 3) a critical isthmus in the inferior-posterior LA with a unidirectional activation pattern at the location where ablation restored sinus rhythm. These patterns were consistently seen in several ECGI movies analyzed for this patient (Online Supplement, Movie 2).

In a second patient, AF organized into atypical flutter following ablation, with variable cycle length (270–310ms) and variable activation sequence as reflected in coronary sinus electrograms. Detailed entrainment mapping suggested the septum to be a critical part of the circuit, and ablation along the posterior septum resulted in sinus rhythm. ECGI during atypical flutter demonstrated a repetitive pattern with a cycle length between 260–410ms involving the septum (Figure 3). Other wavelets were present with this pattern. Online Supplement (Movie 3) shows activation during several cycles of this pattern.

A third patient demonstrated an intermittent driver in the right PVs during mapping and termination of AF with their isolation. ECGI at that time showed frequent right PV focal site activation. This pattern was consistently seen in several ECGI movies. Additional focal sites were seen in other locations during AF, but disappeared after sinus rhythm was restored.

Figure 2. Noninvasive ECGI of AF using a critical isthmus in the posterior LA during AF ablation (Movie 2 in Online Supplement).

Panel A shows a posterior view of the atria with a red star marking the location of the ablation that terminated AF. Panels B and C show ECGI isochrone maps during AF at two separate time points immediately prior to successful ablation. For both images, a wavefront enters the posterior LA (white arrows) through a protected isthmus. Online Movie 2 demonstrates these patterns with continuous AF imaging. LSPV=Left Superior Pulmonary Vein; LIPV=Left Inferior Pulmonary Vein.

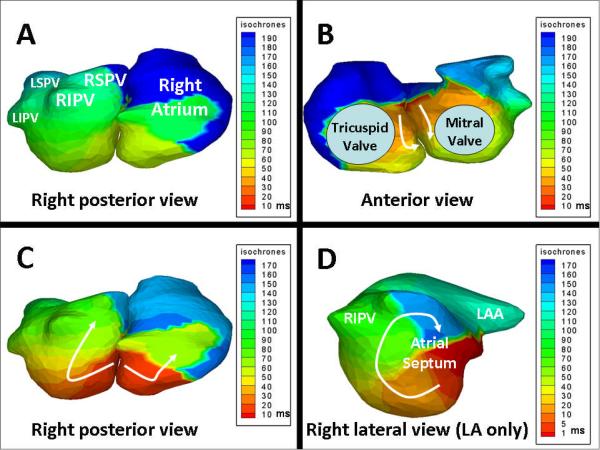

Figure 3. Noninvasive ECGI of atypical atrial flutter during AF ablation (Movie 3 in Online Supplement).

Panels A and B show ECGI isochrone maps of both atria (right posterior and anterior views) during one cycle of atypical flutter. Earliest activation (red) is on the atrial septum in anterior view. Arrows designate the direction of wavefront propagation inferiorly and posterior. Panel C shows a different cycle, and highlights the posterior aspect of the septal reentry circuit. Panel D shows LA alone in right lateral view during flutter. The circus pattern of reentry is clearly seen along the atrial septum (arrow). Wavelets which do not participate in this circuit are present, likely causing variable activation patterns detected by invasive mapping.

STUDY PHASE

Analysis of Atrial Fibrillation

In the study phase of 26 patients, AF imaged with ECGI showed diverse activation patterns.

Number of wavelets: For most patients (24/26, 92%), at least two simultaneous wavelets (range 1–5) were visible. Individually, each patient had a consistent number of wavelets (+/− 1 wavelet). For example, AF judged to have 2 wavelets never had 4 or more wavelets over the course of imaging. Rarely (2/26, 8%), the predominant mechanism was one single wave macroreentry, involving both atria.

Rotors: Rotor pattern was less common (4/26, 15%) and was observed in posterior LA, often near pulmonary vein ostia and occasionally in the anterolateral right atrium (RA). Rotors rarely sustained more than one full rotation before breaking into less organized wavelets. Although the rotors seemed short-lived, in the four patients with rotor patterns, the location of the rotor was reproducible in several ECGI movies. Interestingly, rotors were only seen in patients with non-paroxysmal AF.

Focal sites: Radial epicardial activation from a focus frequently occurred near the pulmonary veins (PV) (18/26, 69%) during AF. Non-PV focal sites were also common (16/26, 62%) and were predominately seen in LA posterior wall, coronary sinus, lateral RA, or vena cavae. By convention, these locations are called focal sites, though their underlying cellular mechanisms and role in initiating AF are not known. These focal sites were seen in addition to simultaneous activation wavelets during AF.

Examples of several AF activation patterns are shown in the following figures. The dynamic activation patterns, often involving several wavelets with wavebreak and shifting pivot points, are best presented in Online Supplement activation movies.

Figure 4 shows two examples of left PV focal sites during AF in a patient with an eight-year history of paroxysmal AF. Radial spread of the activation wavefront is seen, with delay across the posterior LA. Online Movie 4 demonstrates these findings over a longer time period (800ms, or approximately 4 cycles). In addition to the left PV focal sites, a recurring left-to-right activation pattern is seen. One to two simultaneous wavelets are present during AF. These findings were reproducible in 4 of the 5 ECGI movies used for analysis.

Figure 4. Example of left PV focal sites in a patient with paroxysmal AF (Movie 4 in Online Supplement).

Panels A and B show two examples of ECGI isochrone maps of both atria (posterior view) at select times during AF. A focal site is frequently seen near the left PV's (stars) with radial activation spread. Conduction delay (crowded isochrones) is seen in posterior LA. Online Movie 4 demonstrates these patterns with continuous AF imaging, with 1 to 2 simultaneous wavelets predominantly traveling left-to-right.

Figure 5 shows two examples of a focal site with a rotor pattern around a right PV during AF in a patient with a two-year history of persistent AF, refractory to several antiarrhythmic medications. Online Movie 5 shows these findings over a longer time interval (1400ms). Two to three simultaneous wavelets are seen, frequently using RIPV as a pivot. At times, the RIPV has repetitive focal activation, while other times, there is no clear focal activity. These findings were reproducible in 4 of the 5 ECGI movies used for analysis.

Figure 5. Example of rotor pattern and focal site involving RIPV in a patient with persistent AF (Movie 5 in Online Supplement).

Panel A shows a reference image of both atria in posterior view. Panel B shows six time-lapse ECGI images of activation wavefronts (red) in a rotor pattern using RIPV as a pivot. White arrows show the path of wavefronts down the posterior LA and around the RIPV. At 50ms, activation exits the RIPV in a radial pattern. Online Movie 5 shows two to three simultaneous wavelets, frequently using RIPV as a pivot.

Figure 6 demonstrates the less common phenomenon of single wave macroreentry in a young patient with a structurally normal heart and paroxysmal nonsustained AF induced during an EP study. A broad, slow-moving wavefront is seen in both LA and RA. Online Movie 6 is shown with a transparent atrial shell to visualize the entirety of the activation wavefront. No focal sites are detected. This pattern was seen in 5 of 5 ECGI movies used for analysis.

Figure 6. Example of single wave biatrial reentry in a patient with paroxysmal AF (Movie 6 in Online Supplement).

ECGI isochrone map of both atria in the right posterior and anterior views during 100ms of AF demonstrates a single spiral wave. The broad, sweeping activation wavefront involves both atria and propagates predominantly in a counterclockwise fashion (white arrows, anterior view). Although the surface ECG did not demonstrate clear regularity, this pattern on ECGI was highly repetitive. Black line marks the atrial septum. The Online Supplement Movie demonstrates this repetitive pattern.

Figure 7 is an example of a more complex AF pattern in a patient with longstanding persistent AF. Time-lapse images demonstrate rotor patterns near PV ostia and posterior LA. Online Movie 7 shows continuous AF imaging (900ms), demonstrating at least 4 simultaneous wavelets, high degree of wavefront curvature, and frequent wavebreaks. These features were seen in 5 of 5 ECGI movies used for analysis.

Figure 7. Examples of complex rotor physiology in posterior LA in a patient with long-standing persistent AF (Movie 7 in Online Supplement).

Panel A: Activation pattern during AF (46–73ms) of both atria (posterior view). Activation wavelets are shown in red. White arrows indicate propagation direction of the wavelet. The white stars denote pivot points of wavelet rotation. At 46ms, a focal site emerges from LSPV and triggers a wave of radial activation (51ms). The emerging wavelet pivots around an area in the LA posterior wall (59–63ms) (star) and then propagates towards the right PVs (63–73ms). Panel B: Activation pattern during AF at a different time point. A wavelet at 503ms breaks into two on the posterior LA wall (508–525ms) and propagates around two pivot points (stars). At 533ms, the wavelets coalesce and terminate.

Analysis of AF Complexity

Among 26 patients imaged during AF, there were significant differences in the complexity (number of wavelets and focal sites) between the clinical groups (paroxysmal, persistent, long-standing persistent). Patients with paroxysmal AF had fewer wavelets (1.1+/−0.2 wavelets) than patients with persistent AF (2.2+/−0.9 wavelets, p=0.017) or long-standing persistent AF (2.6+/−0.5 wavelets, p<0.005). In aggregate, the three groups were significantly different with regard to number of wavelets (ANOVA p=0.011; Figure 8, Panel A).

Figure 8. AF Complexity.

Panel A: Increasing complexity of atrial fibrillation stratified by clinical classification of paroxysmal, persistent and longstanding persistent AF. With increasing AF duration, ECGI imaged more focal sites and wavelets (ANOVA for wavelet, p = 0.011; focal sites, p = 0.031). Panel B. Complexity Index is the sum of mean number of wavelets and number of focal sites for each patient. A Complexity Index of 1 is the minimum, and represents “simplest” AF. The Complexity Index increases from paroxysmal to persistent to longstanding persistent clinical groups. There is overlap in complexity between persistent and longstanding persistent groups.

Similarly, patients with paroxysmal AF had fewer focal sites (1.0+/−0.7 focal sites) than patients with persistent (2.3+/−1.1 focal sites, p=0.034) or long-standing persistent AF (3.2+/−1.8 focal sites, p=0.034). Compared among the three groups, disparities were significantly different (ANOVA p=0.031; Figure 8, Panel A).

Within the paroxysmal AF group, there was relative homogeneity and simplicity in the number of wavelets and focal sites. Using the sum of the mean number of wavelets and focal sites as a “Complexity Index,” patients with paroxysmal AF had values that ranged from 1 to 3.5, with a mean 2.1 (Figure 8, Panel B). In general, paroxysmal AF patients had 1–2 wavelets with 0–2 focal sites.

In contrast, patients with persistent AF demonstrated considerable heterogeneity. Patients in this group had 1–4 simultaneous wavelets and 1–4 focal sites visible during AF. The complexity index ranged from 2–7, with a mean 4.5. At the extremes, the “simplest” AF pattern among the patients with persistent AF had a single wavelet and a single focal site in the RA (complexity index of 2). The most complex AF pattern in this group had an average of 5 wavelets and at least 2 identifiable focal sites contributing to AF.

The patients with long-standing persistent AF had the most complex AF patterns. One patient in this group who had undergone three prior catheter ablations, exhibited the most complex AF pattern of the entire cohort, with a mean of 3 wavelets arising from a total of 6 identifiable focal sites (two pulmonary veins, coronary sinus, RA, and two sites in the posterior LA). Graphically (Figure 8, Panel B), the persistent and long-standing persistent groups demonstrated overlap with regards to complexity index, while the paroxysmal group did not.

Although patients who have had prior surgical or catheter ablation represent a clinically important type of AF, the effect of previous intervention may introduce artificial complexity to the AF patterns. When these patients were removed from analysis, measurable differences remained between paroxysmal and nonparoxysmal AF regarding the mean number of wavelets (1.1+/−0.2 vs. 1.7+/−0.6, p=0.010), number of focal sites (1.0+/−0.7 vs. 2.6+/−1.1, p=0.015) and complexity index (2.1+/−0.7 vs. 4.4+/−1.5, p=0.007). Patients who underwent prior procedures represented the most complex AF, with a complexity index of 5.2+/−1.9, which was statistically different than native AF (3.6+/−1.7, p=0.043).

Discussion

AF is characterized by a dynamically changing activation sequence.23 This hallmark of AF poses severe limitations on point-by-point catheter mapping of AF, which requires a stable, monomorphic arrhythmia. Simultaneous recording from many electrodes over long duration is required to accurately map AF. Invaluable invasive multi-channel mapping studies have been conducted on epicardial and endocardial atrial surfaces in animals24–31. However, animal models differ from humans in many ways, including ion-channel profiles of atrial myocytes, anatomical substrates, and remodeling processes. Observations from direct epicardial recordings in humans32–35 have been instrumental toward characterization of AF, but are limited, by access to only certain portions of the atria, with relatively short time periods for recording data in an open chest, under influence of general anesthesia on autonomic tone. In other studies, invasive endocardial mapping of AF was performed using multi-channel catheter (basket or balloon) arrays in left and right atria36–39, and pulmonary veins40. Although this approach is less invasive than surgical mapping, it still involves effects of sedation and the intra-atrial presence of the array limits mapping time. The mapping resolution is compromised by limited number of recording electrodes.

The present study applies ECGI as a noninvasive mapping tool for studying mechanisms of human AF. ECGI can map the epicardial activation pattern of AF on both atria continuously and with high spatial resolution. There is no surgery, sedation or invasive intervention involved, therefore the AF pattern can be observed in “real-world” conditions, over long periods of time (minutes to hours). The pacing data presented here determine ECGI's atrial accuracy at 6mm, which is comparable to previously published data from ventricular ECGI reconstructions. The overlap of clinical findings from EP catheter mapping and ablation with simultaneous ECGI corroborates the noninvasive findings.

This study is the first to report detailed, three-dimensional mapping of biatrial epicardial activation during AF in humans. Major findings include: 1) ECGI is feasible in most patients, even with low amplitude fibrillatory atrial signals; 2) epicardial activation patterns are variable within the population, but specific and reproducible activation patterns are present in individual patients; 3) the most common activation pattern consisted of multiple concurrent wavelets with simultaneous focal sites from areas near the pulmonary veins; 4) complexity of AF increased with duration-based clinical classification of AF, though; 5) among persistent and long-standing persistent AF, there was overlap in complexity.

The human data presented here are consistent with models of AF mechanisms24–31 and highlight the coexistence of a variety of mechanisms, as reported in animals and humans.9–12, 32–40 Specifically, the number of simultaneous wavelets (1–5) and the observation that the wavelets change position from beat to beat is consistent with direct epicardial mapping of Allessie.24,35 The frequency of pulmonary vein focal sites is consistent with findings of Haissaguerre.11 The observation of rotor patterns in certain areas (posterior LA, pulmonary veins, lateral RA) is consistent with observations of Jalife.10 Although rare, single wavelet reentry was described by Cox.32 The relative contribution of each mechanism to initiation and maintenance of AF remains to be determined.

Data reported here have implications for treatment of AF. Our observation that patients with paroxysmal AF have simpler activation patterns, often involving the pulmonary veins, could explain the greater success rates of catheter ablation in these patients. On the other hand, the wide range of AF complexity and mechanisms in non-paroxysmal AF, including rotor activity in areas not usually targeted for ablation, may help explain variability of reported ablation success in these patients. Additionally, persistent AF may be simple and relatively organized in one patient (Figure 5), but quite complex in another (Figure 7). Clinical categories do not reliably reflect AF complexity. As such, ECGI may have a role identifying persistent AF patients who would be more likely to benefit from an ablation procedure or antiarrhythmic drug41. Conversely, ECGI may identify patients who are unlikely to benefit from catheter or surgical ablation due to complex atrial activation patterns that may be difficult to treat with current strategies. Finally, ECGI offers an opportunity to noninvasively follow therapy (pharmacological or procedural) outcome over time, and better understand why AF recurs in some patients.

The AF activation patterns were often repeated in a given patient. However, the repetition of patterns decreased in more complex AF. The data were collected over a period of minutes to hours, so the long-term reproducibility of AF patterns remains unanswered. Establishing reproducibility will be key to patient-specific pre-ablation strategy, tailored to the AF pattern of an individual patient by indicating which areas to target as focal sources.

Several key limitations are worth noting. First, ECGI reconstructs potentials on the atrial epicardial surface. While atria are generally thin, evolving evidence suggests at least a modest difference between endocardial and epicardial activation. The observation described as a “focal site” may well be epicardial breakthrough of intramural activation. Second, ECGI images cannot differentiate micro-reentry from focal activity. Third, this first ECGI AF study was aimed at obtaining data from a wide range of phenotypes. The effect of previous catheter ablation and surgery may confound the association between long-standing AF duration and complexity. Future studies should focus on each subgroup with greater detail. Additionally, validation of AF activation patterns with correlative invasive data was only available for three out of the 26 patients. Ongoing prospective studies are investigating the dynamic changes of AF mechanisms during catheter ablation, which may provide additional correlative invasive data. Finally, a limitation for ECGI is the inherent AF signal quality, which is often low amplitude on the body surface. By considering at least five AF activation movies (ranging from 500–1000ms) for each patient and limiting the definition of focal site to cycle lengths of at least 100ms, nonphysiologic artifacts were minimized.

In conclusion, ECGI can noninvasively image electrical activation during AF in a wide range of patients. In this initial feasability study, a variety of AF mechanisms coexisted and complexity increased with longer duration of AF. If the ability of ECGI to distinguish AF activation patterns among the clinically defined subgroups is validated further in larger prospective studies utilizing invasive recordings, this noninvasive technology has the potential to advance our understanding regarding AF mechanisms. Ultimately, ECGI could be utilized clinically to form individualized, mechanism-based treatment plans. This later hypothesis requires testing in randomized trials.

CLINICAL SUMMARY.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, accountable for frequent hospitalizations and increased risks of stroke, heart failure, and mortality. Various mechanisms of AF have been demonstrated in experimental models. Invasive methods to study these mechanisms in humans have limitations, precluding continuous mapping of both atria with sufficient resolution in a closed chest. This paper presents simultaneous biatrial epicardial activation sequences during AF for a range of AF phenotypes in 26 patients, obtained noninvasively using Electrocardiographic Imaging (ECGI).

From a diagnostic standpoint, ECGI offers a way to describe a particular patient's AF using continuous nonivasive mapping of atrial electrical activity. By imaging atrial electrophysiology, it offers an advantage over the current classification of AF, which relies on historical descriptors of duration and method of AF termination (paroxysmal, persistent or permanent). Better identification of specific phenotypes ultimately may translate into tailored, patient-specific treatment plans that maximize benefit while minimizing risk. Examples include predicting and monitoring response to antiarrhythmic drug therapy, or developing a customized catheter ablation lesion set. In this paper, locations critical to maintenance of AF were identified in three patients during catheter ablation procedures and correlated with the ECGI findings. Ablation near these sites restored sinus rhythm. Prospective studies in homogeneous phenotypic subgroups would be needed to better define the role of ECGI in the treatment of patients with AF.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was supported by NIH-NHLBI Merit Award R37-HL-33343 and R01-HL-49054 (to Y. Rudy). Dr. Rudy is the Fred Saigh Distinguished Professor at Washington University. Drs. Damiano and Schuessler are supported by R01-HL-032257, R01-HL-085113.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Lindsay and Dr. Rudy are members of the scientific advisory board of CardioInsight Technologies, Inc. Dr. Rudy holds equity in CardioInsight Technologies. CardioInsight Technologies does not support any research conducted by Dr Rudy, including that presented here.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJ. A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am J Med. 2002;113:359–64. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wattigney WA, Mensah GA, Croft JB. Increasing trends in hospitalization for atrial fibrillation in the United States, 1985 through 1999. Circulation. 2003;108:711–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000083722.42033.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Le Heuzey JY, Kay GN, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann S, Smith SC, Jr., Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Hunt SA, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm AJ, Dean V, Deckers JW, Despres C, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Zamorano JL. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2006;114:e257–354. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.177292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jalife J, Berenfeld O, Mansour M. Mother rotors and fibrillatory conduction: a mechanism of atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:204–16. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YJ, Chen SA. Electrophysiology of pulmonary veins. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:220–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2005.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allessie M, Ausma J, Schotten U. Electrical, contractile and structural remodeling during atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:230–46. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Everett TH, Wilson EE, Verheule S, Guerra JM, Foreman S, Olgin JE. Structural atrial remodeling alters the substrate and spatiotemporal organization of atrial fibrillation: a comparison in canine models of structural and electrical atrial remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2911–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01128.2005.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nattel S. New ideas about atrial fibrillation 50 years on. Nature. 2002;415:219–26. doi: 10.1038/415219a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moe GK, Rheinboldt WC, Abildskov JA. A Computer Model of Atrial Fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1964;67:200–20. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(64)90371-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jalife J, Berenfeld O, Skanes A, Mandapati R. Mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: mother rotors or multiple daughter wavelets, or both? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1998;9:S2–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haissaguerre M, Jais P, Shah DC, Takahashi A, Hocini M, Quiniou G, Garrigue S, Le Mouroux A, Le Metayer P, Clementy J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:659–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809033391003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hou Y, Scherlag BJ, Lin J, Zhang Y, Lu Z, Truong K, Patterson E, Lazzara R, Jackman WM, Po SS. Ganglionated plexi modulate extrinsic cardiac autonomic nerve input: effects on sinus rate, atrioventricular conduction, refractoriness, and inducibility of atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, Cappato R, Chen SA, Crijns HJ, Damiano RJ, Jr., Davies DW, Haines DE, Haissaguerre M, Iesaka Y, Jackman W, Jais P, Kottkamp H, Kuck KH, Lindsay BD, Marchlinski FE, McCarthy PM, Mont JL, Morady F, Nademanee K, Natale A, Pappone C, Prystowsky E, Raviele A, Ruskin JN, Shemin RJ. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert Consensus Statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:816–61. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramanathan C, Ghanem RN, Jia P, Ryu K, Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac electrophysiology and arrhythmia. Nat Med. 2004;10:422–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramanathan C, Jia P, Ghanem R, Ryu K, Rudy Y. Activation and repolarization of the normal human heart under complete physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601533103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Rudy Y. Electrocardiographic imaging of normal human atrial repolarization. Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:582–3. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durrer D, Van Dam R, Freud GE, Janse MJ, Meijler FL, Arzbaecher RC. Total excitation of the isolated human heart. Circulation. 1970;41:899–912. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.41.6.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Cuculich PS, Woodard PK, Lindsay BD, Rudy Y. Focal atrial tachycardia after pulmonary vein isolation: noninvasive mapping with electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI) Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1081–4. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cuculich PS, Wang Y, Lindsay BD, Vijayakumar R, Rudy Y. Noninvasive real-time mapping of an incomplete pulmonary vein isolation using electrocardiographic imaging. Heart Rhythm, epub. 2009 Nov 11; doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Schuessler RB, Damiano RJ, Woodard PK, Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging (ECGI) of scar-related atypical atrial flutter. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:1565–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oster HS, Taccardi B, Lux RL, Ershler PR, Rudy Y. Noninvasive electrocardiographic imaging: reconstruction of epicardial potentials, electrograms, and isochrones and localization of single and multiple electrocardiac events. Circulation. 1997;96:1012–24. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.3.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox J, Schuessler R, D'Agostino H, Stone C, Chang B, Cain M, Corr P, Boineau J. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. Development of a definitive surgical procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101:569–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis T, Meakins J, White PD. The excitatory process in the dog's heart. Part I: The Auricles. Phil Trans Roy Soc B. 1914;205:322–416. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allessie MA, Lammers W, Bonte F, Hollen J. Cardiac Electrophysiology and Arrhythmias. Grune and Stratton; Orlando, FL: 1985. pp. 265–275. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schuessler RB, Kawamoto T, Hand DE, Mitsuno M, Bromberg BI, Cox JL, Boineau JP. Simultaneous epicardial and endocardial activation sequence mapping in the isolated canine right atrium. Circulation. 1993;88:250–63. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.1.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sih HJ, Zipes DP, Berbari EJ, Adams DE, Olgin JE. Differences in organization between acute and chronic atrial fibrillation in dogs. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:924–31. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00788-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derakhchan K, Li D, Courtemanche M, Smith B, Brouillette J, Page PL, Nattel S. Method for simultaneous epicardial and endocardial mapping of in vivo canine heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:548–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mansour M, Mandapati R, Berenfeld O, Chen J, Samie FH, Jalife J. Left-to-right gradient of atrial frequencies during acute atrial fibrillation in the isolated sheep heart. Circulation. 2001;103:2631–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.21.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun H, Velipasaoglu EO, Wu DE, Kopelen HA, Zoghbi WA, Spencer WH, Khoury DS. Simultaneous multisite mapping of the right and the left atrial septum in the canine intact beating heart. Circulation. 1999;100:312–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumagai K, Khrestian C, Waldo AL. Simultaneous multisite mapping studies during induced atrial fibrillation in the sterile pericarditis model. Circulation. 1997;95:511–21. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kadish A, Hauck J, Pederson B, Beatty G, Gornick C. Mapping of atrial activation with a noncontact, multielectrode catheter in dogs. Circulation. 1999;99:1906–13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.14.1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox JL, Canavan TE, Schuessler RB, Cain ME, Lindsay BD, Stone C, Smith PK, Corr PB, Boineau JP. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. II.Intraoperative electrophysiologic mapping and description of the electrophysiologic basis of atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101:406–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson TB, Jr., Schuessler RB, Hand DE, Boineau JP, Cox JL. Lessons learned from computerized mapping of the atrium. Surgery for atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter. J Electrocardiol. 1993;26(Suppl):210–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahadevan J, Ryu K, Peltz L, Khrestian CM, Stewart RW, Markowitz AH, Waldo AL. Epicardial mapping of chronic atrial fibrillation in patients. Circulation. 2004;110:3293–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147781.02738.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konings KTS, Kirchhof CJHJ, Smeets JRLM, Wellens HJ, Penn OC, Allessie MA. High density mapping of electrically induced atrial fibrillation in humans. Circulation. 1994;89:1665–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schilling RJ, Kadish AH, Peters NS, Goldberger J, Davies DW. Endocardial mapping of atrial fibrillation in the human right atrium using a non-contact catheter. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:550–64. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Markides V, Schilling RJ, Ho SY, Chow AW, Davies DW, Peters NS. Characterization of left atrial activation in the intact human heart. Circulation. 2003;107:733–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000048140.31785.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Earley MJ, Abrams DJ, Sporton SC, Schilling RJ. Validation of the noncontact mapping system in the left atrium during permanent atrial fibrillation and sinus rhythm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:485–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi Y, Hocini M, O'Neill MD, Sanders P, Rotter M, Rostock T, Jonsson A, Sacher F, Clementy J, Jais P, Haissaguerre M. Sites of focal atrial activity characterized by endocardial mapping during atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2005–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.De Ponti R, Tritto M, Lanzotti ME, Spadacini G, Marazzi R, Moretti P, Salerno-Uriarte JA. Computerized high-density mapping of the pulmonary veins. Europace. 2004;6:97–108. doi: 10.1016/j.eupc.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li D, Bénardeau A, Nattel S. Contrasting Efficacy of Dofetilide in Differing Experimental Models of Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2000;102:104–12. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.