Abstract

Effectiveness of double umbilical cord blood (dUCB) grafts relative to conventional marrow and mobilized peripheral blood from related and unrelated donors has yet to be established. We studied 536 patients at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and University of Minnesota with malignant disease who underwent transplantation with an human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched related donor (MRD, n = 204), HLA allele–matched unrelated donor (MUD, n = 152) or 1-antigen–mismatched unrelated adult donor (MMUD, n = 52) or 4-6/6 HLA matched dUCB (n = 128) graft after myeloablative conditioning. Leukemia-free survival at 5 years was similar for each donor type (dUCB 51% [95% confidence interval (CI), 41%-59%]; MRD 33% [95% CI, 26%-41%]; MUD 48% [40%-56%]; MMUD 38% [95% CI, 25%-51%]). The risk of relapse was lower in recipients of dUCB (15%, 95% CI, 9%-22%) compared with MRD (43%, 95% CI, 35%-52%), MUD (37%, 95% CI, 29%-46%) and MMUD (35%, 95% CI, 21%-48%), yet nonrelapse mortality was higher for dUCB (34%, 95% CI, 25%-42%), MRD (24% (95% CI, 17%-39%), and MUD (14%, 95% CI, 9%-20%). We conclude that leukemia-free survival after dUCB transplantation is comparable with that observed after MRD and MUD transplantation. For patients without an available HLA matched donor, the use of 2 partially HLA-matched UCB units is a suitable alternative.

Introduction

Umbilical cord blood (UCB) has been shown to be a valuable alternative source of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) for transplantation in patients who lack a suitable related or unrelated donor.1–9 Cell dose is the single most important determinant of successful UCB transplantation in adult patients.10–13 Transplantation of a single UCB unit containing a (prefreeze) cell dose < 2.5 × 107 nucleated cells per kilogram or an infused CD34 cell dose of < 1.7 × 105 nucleated cells per kilogram has been associated with poor engraftment, high nonrelapse mortality (NRM), and poor survival.11 The infusion of 2 partially human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–matched UCB units was explored as a strategy to achieve this cell dose threshold and make UCB more widely available.14–17 However, to date, the risks and benefits of double UCB transplantation (dUCBT) relative to those observed after transplantations with related and unrelated adult donors have yet to be determined.

Methods

Study design and patient selection

Consecutive patients age ≥ 10 years and undergoing first allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for hematologic malignancy after a high-dose total body irradiation containing conditioning regimen at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (FHCRC) and University of Minnesota (UM) between 2001 and 2008 were eligible for this retrospective analysis. Patients had human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–8/8 allele–matched related donors (MRD) or matched unrelated donors (MUD), 1 allele– mismatched unrelated donors (MMUD), or a dUCB graft. All UCB units were HLA-typed at the antigen-level for HLA-A and HLA-B and allele-level for HLA-DRB1. As previously reported, UCB units were HLA 4-6/6 matched with the patient and each other.14 All patients received myeloablative conditioning with cyclophosphamide 120 mg/kg and total body irradiation 1200 to 1320 cGy with the addition of fludarabine 75 mg/m2 in recipients of dUCBT, and graft–versus–host disease immunoprophylaxis with a calcineurin inhibitor (cyclosporine or tacrolimus) and either methotrexate (MRD, MUD, and MMUD) or mycophenolate mofetil (MRD and dUCB). Supportive care was similar in the 2 centers and included anti-infective prophylaxis in single hospital rooms with high-efficiency particulate air filtration. Antiviral prophylaxis included acyclovir until day 100. Documented cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation or infection was treated with ganciclovir or foscarnet. Broad spectrum antibiotics were administered for neutropenic fever and antifungal coverage was added for persistent fever. All patients received fluconazole or voriconazole for prophylaxis of fungal infections for 100 days and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for prophylaxis of Pneumocystis jiroveci. Extended spectrum fluoroquinolones were administered for encapsulated bacterial prophylaxis during treatment of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

Endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint of this study was leukemia-free survival (LFS) defined as the time from transplantation to first relapse or death during complete remission. Other endpoints included the cumulative incidences of neutrophil recovery (≥ 500/μL by day +45) and platelet recovery (≥ 50 000/μL at day +100 after transplantation) with complete chimerism, cumulative incidence of acute and chronic GVHD at 3 months and 2 years, respectively, and cumulative incidences of NRM at 2 years and relapse at 5 years. Acute and chronic GVHD were recognized and scored using standardized criteria.18,19 Patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) in first complete remission (CR1) or second complete remission (CR2) and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) in first chronic phase (CP1) were considered standard risk of relapse. All remaining patients were considered high risk. For dUCBT recipients, HLA-matching was defined by the worst matched of the 2 units (eg, if one unit was 5/6 and the other 4/6 matched, it was analyzed as a 4/6 HLA-matched graft).

Statistical considerations

Cumulative incidence was used to estimate the endpoints of hematopoietic recovery, relapse, NRM, and acute and chronic GVHD. For neutrophil and platelet recovery and GVHD, death without the event was the competing event. For NRM, relapse was the competing event; for relapse, transplant-related death was the competing event.20 LFS was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method.21 Comparisons of time-to-event curves were completed by the logrank test. Cox regression was used to assess factors influencing LFS and neutrophil engraftment.22 The proportional hazards model of Fine and Gray was used to assess independent factors on platelet engraftment, acute and chronic GVHD, relapse and NRM.23 All factors were tested for proportional hazards before inclusion in the regression models.24 Factors considered in the multivariable models were donor type (MRD vs MUD vs MMUD vs DUCB), diagnosis (ALL vs AML vs CML vs myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS]), disease risk (standard vs high), age (continuous), weight, sex, sex-mismatch, CMV serostatus (donor and recipient negative vs either positive) and time from diagnosis to transplantation (< 1 year vs 1-2 years vs > 2 years). All P-values were 2-sided. The median follow up of survivors was 3.1 years (range, 0.3-8.1 years).

Analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute) and R 2.4 statistical software. This retrospective analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board of both institutions.

Results

Patient and graft characteristics

Patient and graft characteristics for the 536 patients are shown in Table 1. Patients were transplanted at FHCRC (n = 322) and UM (n = 214) for the treatment of AML (n = 211), ALL (n = 236), CML (n = 70), and MDS (n = 19). Allografts were from a MRD (n = 204), MUD (n = 152), MMUD (n = 52), or dUCB (n = 128). Differences between donor groups included, higher median age in MRD recipients, more frequent diagnosis of CML in recipients of MUD or MMUD grafts, lower incidence of CMV seropositivity in recipients of MUD grafts, and greater HLA mismatch and shorter follow-up in recipients of dUCB. Sex distribution and disease risk were similar between groups. Peripheral blood stem cells (PBSCs) were used for nearly all MRD grafts (92%) and most MUD grafts (58%) with marrow used more frequently for MMUD grafts (65%). While proportions of patients with MRD grafts were similar between the 2 institutions, MUD and MMUD grafts were more commonly used at FHCRC and dUCB was more commonly used at UM. As expected, dUCB grafts contained fewer nucleated cells. The median infused cell doses of the larger and smaller UCBs unit were 2.1 × 107/kg (range, 1.1-22.0) and 1.6 × 107/kg (range, 0.6-15) actual recipient body weight, respectively. Only 29 of the 256 infused UCB units contained an infused cell dose ≥ 3.0/kg of recipient weight.

Table 1.

Patient and graft characteristics

| Factors | dUCB | MRD | MUD | MMUD | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 128 | 204 | 152 | 52 | NE |

| Median age at transplantation, y (range) | 25 (10-46) | 40 (12-67) | 31 (10-57) | 31 (10-51) | < .01 |

| Median weight, kg (range) | 72 (32-149) | 78 (12-67) | 76 (26-137) | 76 (34-145) | < .11 |

| Male | 72 (56%) | 120 (59%) | 95 (63%) | 31 (60%) | < .76 |

| Recipient CMV+ | 79 (62%) | 119 (58%) | 67 (44%) | 31 (60%) | < .01 |

| Diagnosis | < .01 | ||||

| ALL | 48 (38%) | 80 (39%) | 67 (44%) | 16 (31%) | |

| AML | 68 (53%) | 97 (48%) | 50 (33%) | 21 (40%) | |

| CML | 8 (6%) | 15 (7%) | 32 (21%) | 15 (29%) | |

| MDS | 4 (3%) | 12 (6%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | |

| High-risk disease | 65 (51%) | 112 (55%) | 93 (61%) | 35 (67%) | < .13 |

| Disease status at transplantation | < .01 | ||||

| Acute leukemia CR1 | 58 (45%) | 89 (44%) | 44 (29%) | 13 (25%) | |

| Acute leukemia CR2 | 42 (33%) | 42 (21%) | 42 (28%) | 11 (21%) | |

| Acute leukemia CR3+ | 16 (13%) | 46 (23%) | 31 (20%) | 13 (25%) | |

| CML 1st chronic phase | 5 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (8%) | 5 (4%) | |

| CML accelerated phase | 3 (2%) | 12 (6%) | 17 (11%) | 11 (21%) | |

| Stem cell source | NE | ||||

| BM | NA | 17 (8%) | 64 (42%) | 18 (35%) | |

| PBSCs | NA | 187 (92%) | 88 (58%) | 34 (65%) | |

| dUCB | 128 (100%) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Nucleated cell dose (108/kg) | 0.4 (0.2-3.0) | 8.6 (1.6-22.2) | 2.0 (1.1-14.2) | 1.7 (1.6-1.9) | < .01 |

| HLA-matching* | NE | ||||

| 8/8 | NA | NA | 152 | NA | |

| 7/8 | NA | NA | NA | 52 | |

| 6/6 | NA | 204 | NA | NA | |

| 6/6 + 6/6 | 5 (4%) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 6/6 + 5/6 | 4 (3%) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 6/6 + 4/6 | 1 (1%) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 5/6 + 5/6 | 41 (32%) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 5/6 + 4/6 | 20 (16%) | NA | NA | NA | |

| 4/6 + 4/6 | 57 (45%) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Transplant center | < .01 | ||||

| FHCRC | 24 (19%) | 110 (54%) | 138 (91%) | 50 (96%) | |

| UM | 104 (81%) | 94 (46%) | 14 (9%) | 2 (4%) | |

| Median follow-up, y (range) | 2.1 (0.4-6.9) | 3.0 (0.4-7.5) | 4.2 (0.3-8.1) | 4.8 (2.0-7.5) | < .01 |

NE indicates not evaluable; CMV+, cytomegalovirus seropositive; CR1, first complete remission; CR2, second complete remission; CR3+, third completed remission, primary induction failures and active leukemia; and NA, not applicable.

As defined in “Study design and patient selection,” the degree of HLA-matching varies depending on the donor type.

Leukemia-free survival

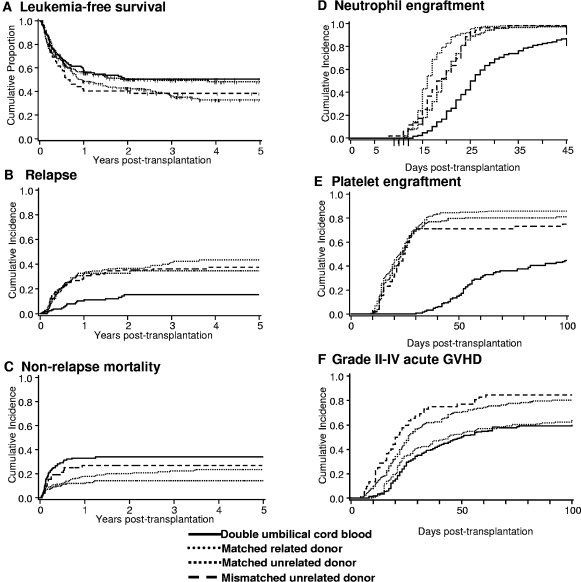

The primary endpoint of this analysis was LFS. As shown in Figure 1A and Table 2, LFS at 5 years was similar for all 4 groups. After adjusting for disease risk and time from diagnosis to transplantation, multivariable analysis did not reveal any difference in the relative risk of LFS by donor type (Table 3). In patients with acute leukemia transplanted with a MUD graft, no difference in the relative risk of LFS was observed between recipients of bone marrow (BM, reference group) and PBSC (RR 1.39 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.74-2.59], P = .31). LFS was similar for patients treated at each transplant center (data not shown). For patients ≤ 45 years (the maximum age for recipients of a myeloablative regimen and dUCBT by design), LFS at 5 years remained similar (Table 2). Additional analyses revealed similar probabilities of LFS for all donor types when restricted to patients ≥ 18 years (n = 450; dUCB, relative risk [RR] 1.0 [reference group]; MRD RR 0.97, 95% CI, 0.69-1.37, P = .86; MUD RR 0.79, 95% CI, 0.53-1.17, P = .24; MMUD RR 1.07, 95% CI, 0.67-1.69, P = .78), and those with acute leukemia (dUCB, RR 1.0 [reference group]; MRD RR 1.09, 95% CI, 0.78-1.52, P = .62; MUD RR 1.01, 95% CI, 0.69-1.48, P = .96; MMUD RR 0.97, 95% CI, 0.58-1.62, P = .89).

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes. (A) LFS, (B) relapse, (C) NRM, (D) neutrophil engraftment, (E) platelet engraftment, and (F) grade 2-4 acute GVHD after dUCB, MRD, MUD, and MMUD transplantation.

Table 2.

Study end points

| End point | dUCB % (95% CI) | MRD % (95% CI) | MUD % (95% CI) | MMUD % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFS at 5 y | 51 (41-59) | 33 (26-41) | 48 (40-56) | 38 (25-51) |

| ≤ 45 y | 51 (41-59) | 31 (21-40) | 50 (41-58) | 34 (21-48) |

| Relapse at 5 y | 15 (9-22) | 43 (35-52) | 37 (29-46) | 35 (21-48) |

| ≤ 45 y | 16 (9-23) | 52 (41-63) | 37 (29-46) | 39 (24-54) |

| Disease free* | 17 (9-25) | 42 (33-51) | 30 (21-39) | 32 (17-47) |

| NRM at 5 y | 34 (25-42) | 24 (17-39) | 14 (9-20) | 27 (15-39) |

| Acute GVHD at 100 d | ||||

| Grade II-IV | 60 (50-70) | 65 (57-73) | 80 (70-90) | 85 (68-100) |

| Grade III-IV | 22 (15-29) | 13 (9-18) | 14 (9-20) | 37 (23-50) |

| Chronic GVHD at 2 y | 26 (15-35) | 47 (39-55) | 43 (34-52) | 48 (32-64) |

| End point | Median dUCB (range) | Median MRD (range) | Median MUD (range) | Median MMUD (range) |

| Neutrophil recovery at 45 d | 26 (13-45) | 16 (11-39) | 19 (11-39) | 18.5 (8-33) |

| Platelet recovery at 100 d | 53 (30-99) | 20 (9-63) | 21 (10-95) | 21 (10-98) |

Survivors who were disease free at day +100 after transplantation.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of outcomes

| End point* | RR or odds ratio (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| LFS #1† | ||

| Double UCB donor‡ | 1.0 | |

| MRD | 1.09 (0.80-1.49) | .59 |

| MUD | 0.85 (0.61-1.20) | .36 |

| MMUD | 1.12 (0.73-1.73) | .60 |

| Leukemia relapse§ | ||

| Double UCB donor‡ | 1.0 | |

| MRD | 3.67 (2.14-6.27) | < .01 |

| MUD | 3.05 (2.14-6.27) | < .01 |

| MMUD | 2.50 (1.23-5.07) | < .01 |

| NRM§ | ||

| Double UCB donor‡ | 1.0 | |

| MRD | 0.31 (0.18-0.53) | < .01 |

| MUD | 0.61 (0.33-1.15) | < 13 |

| MMUD | 0.38 (0.24-0.59) | < .01 |

| Neutrophil recovery† | ||

| Double UCB donor‡ | 1.0 | |

| MRD | 3.46 (2.69-4.44) | < .01 |

| MUD | 2.16 (1.69-2.75) | < .01 |

| MMUD | 2.17 (1.55-3.03) | < .01 |

| Platelet recovery§ | ||

| Double UCB donor‡ | 1.0 | |

| MRD | 4.55 (3.46-5.99) | < .01 |

| MUD | 3.80 (2.77-5.22) | < .01 |

| MUDD | 3.23 (2.13-4.90) | < .01 |

| Grade II-IV acute GVHD§ | ||

| Double UCB donor‡ | 1.0 | |

| MRD | 1.08 (0.82-1.43) | .57 |

| MUD | 1.83 (1.36-2.47) | < .01 |

| MMUD | 2.35 (1.52-3.63) | < .01 |

| Chronic GVHD§ | ||

| Double UCB donor‡ | 1.0 | |

| MRD | 1.58 (1.03-2.43) | .03 |

| MUD | 1.71 (1.12-2.63) | .01 |

| MMUD | 2.07 (1.19-3.60) | .01 |

Other factors that were significant in multivariable analysis for LFS: High risk disease RR 2.44 (95%CI, 1.8-3.21), P < .01. Years from diagnosis to transplantation, 1 to 2 years RR 0.58 (95%CI, 0.42-0.81), P < .01, > 2 years RR 0.44 (95%CI, 0.31-0.61), P < .01. Significant for leukemia relapse: High risk disease RR 3.07 (95%CI, 2.12-4.43), P < .01. Age at transplantation (continuous/decade) RR 0.86 (95%CI, 0.76-0.96), P < .01. Years from diagnosis to transplantation, 1 to 2 years RR 0.57 (95%CI, 0.38-0.87), P < .01, > 2 years RR 0.30 (95%CI, 0.18-0.48), P < .01. MDS RR 0.07 (95%CI, 0.01-0.51), P < .01. Significant for NRM: Age at transplantation (continuous/decade) RR 1.30 (95%CI, 1.12-1.51), P < .01; AML RR 0.63 (95%CI, 0.42-0.96), P = .03; MDS RR 3.06 (95%CI, 1.53-6.15), P < .01. Significant for neutrophil recovery: Age at transplantation (continuous/decade) RR 1.08 (95%CI, 1.00-1.16), P = .04. Significant for platelet recovery: MDS RR 0.29 (95%CI, 0.14-0.60), P < .01.Significant for grade II-IV acute GVHD: Donor or recipient seropositive RR 0.73 (95%CI, 0.59-0.89), P < .01. Significant for chronic GVHD: Age at transplantation (continuous/decade) RR 1.16 (95%CI, 1.04-1.30), P < .01.

Cox regression.

Denotes reference group.

Proportional hazards model of Fine and Gray.

Relapse

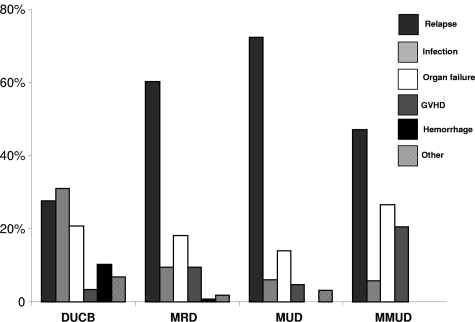

The cumulative incidence of relapse at 5 years was comparable in recipients of MRD, MUD, and MMUD grafts but lower in recipients of dUCBT (Figure 1B) with similar outcomes in the subset of patients ≤ 45 years (Table 2). Because the incidence of early NRM was highest after dUCBT (see “Nonrelapse mortality”), we analyzed the risk of relapse in survivors who were leukemia free at day +100 after transplantation (dUCB = 92, MRD = 163, MUD = 117, and MMUD = 38). In this subgroup, the risk of relapse remained lowest in recipients of dUCB (Table 2). After adjusting for disease risk, interval from diagnosis to transplantation, age at transplantation and diagnosis, multivariable analysis showed lower relative risk of relapse was associated with dUCBT (Table 3). Similarly, the relative risk of relapse remained lower among dUCBT recipients regardless of risk group (for high risk patients: dUCB, RR 1.0 [reference group]; MRD RR 3.64, 95% CI, 1.1.89-7.01, P < .01; MUD RR 3.36, 95% CI, 1.73-6.53, P = .02; MMUD RR 2.61, 95% CI, 1.18-5.77, P = .02, and for standard risk disease: dUCB, RR 1.0 [reference group]; MRD RR 4.42, 95% CI, 1.82-10.73, P < .01; MUD RR 3.25, 95% CI, 1.22-8.66, P = .02; MMUD RR 3.33, 95% CI, 0.91-12.19, P = .07). Additional ana-lyses revealed similar outcomes when restricted to patients ≥ 18 years (dUCB, RR 1.0 [reference group]; MRD RR 3.59, 95% CI, 1.94-6.65, P < .01; MUD RR 2.76, 95% CI, 1.41-5.40, P < .01; MMUD RR 2.28, 95% CI, 1.04-5.01, P = .04); or those with acute leukemia (dUCB, RR 1.0 [reference group]; MRD RR 3.86, 95% CI, 2.22-6.72, P < .01; MUD RR 3.41, 95% CI, 1.90-6.09, P < .01; MMUD RR 2.18, 95% CI, 0.99-4.79, P = .05). Leukemia relapse was the most frequent cause of mortality in recipients of MRD, MUD, and MMUD grafts (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of causes of death after dUCB, MRD, MUD, and MMUD transplantation.

Nonrelapse mortality

The cumulative incidence of NRM at 2 years was highest in recipients of dUCB (Figure 1C and Table 2). After adjusting for age at transplantation and diagnosis, multivariable analysis showed that the risk of NRM was higher after dUCBT (Table 3). Analysis of risk factors for NRM among dUCB recipients demonstrated a higher risk in patients with delayed neutrophil recovery (41% [95% CI, 26%-56%] if neutrophil recovery took ≥ 26 days (median time to neutrophil recovery for dUCB recipients) compared 16% [95% CI, 7%-25%] if recovery was < 26 days). If restricted to dUCB recipients with earlier (< median 26 days) to neutrophil recovery after dUCBT, the incidence of NRM was similar in all groups (dUCB, RR 1.0 [reference group]; MRD RR 0.5 [95% CI, 0.2-1.1] P = .07; MUD RR 0.7 [95% CI, 0.3-1.4], P = .30; MMUD RR 1.5 [95% CI, 0.6-3.6], P = .39]), emphasizing that delayed engraftment is the single greatest barrier to successful UCBT and the most important contributor to early NRM. As shown in Figure 2, infection was the most common cause of death among recipients of dUCB.

Hematopoietic recovery and GVHD

While the use of dUCB broadens the application of UCB as a stem cell source, hematopoietic recovery in recipients of dUCB remains delayed relative to other donor sources. As shown in Table 2, the median times to neutrophil and platelet recovery are at least 1 week and 4 weeks longer after dUCBT, respectively (Table 2) with lower cumulative incidences of recovery (Figure 1D-E). In multivariable analysis, neutrophil and platelet recovery were slower in recipients of dUCB compared with other donor sources (Table 3), after adjusting for recipient's age and diagnosis, respectively.

Despite greater HLA mismatch, the cumulative incidence of grade 2-4 acute GVHD was lowest in recipients of dUCB (Table 2, Figure 1F). In multivariable analysis, after adjusting for CMV serostatus, a higher relative risk of grade 2-4 GVHD was associated with MUD or MMUD transplantation (Table 3). In contrast, the cumulative incidence of grade 3-4 acute GVHD was lowest in recipients of MRD grafts (Table 2). With regards to chronic GVHD, the cumulative incidence was lowest among recipients of dUCB (Table 2) even after adjusting for differences in patient age (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study is the first analysis comparing the relative risks and benefits of dUCB with MRD, MUD, and MMUD as sources of allogeneic HSCs for transplantation. In this study, we found that myeloablative conditioning followed by dUCBT is associated with similar rates of LFS compared with adult donor types. While delayed engraftment and the resulting higher risk of early NRM remain barriers to the successful use of dUCBT, marked reduction in relapse risk and lower risks of acute and chronic GVHD are advantages.

Registry and single center-based studies have previously shown that outcomes after UCBT using single unit grafts containing an adequate number of cells are comparable with that observed after the transplantation of marrow or peripheral blood from HLA-MRD or -MUD.4–8,16,17,25,26 Despite the reduction in HLA matching requirements, the low cell dose in a UCB graft has markedly restricted the use of UCB as the majority of adults cannot find a single UCB unit that provides the recommended nucleated cell dose of 2.5 × 107/kg.11 To overcome the cell dose barrier, we first established the safety of dUCB transplantation.14 This study extends observations in earlier smaller studies and provides the first compelling evidence that dUCB units broadens the application of UCB to larger recipients and results in a LFS comparable with that observed using the gold standard of HLA-MRD and -MUD.

In addition to demonstrating a similar LFS, one of most intriguing findings of this study is the marked reduction in risk of relapse after dUCBT. While we and others have shown a reduced risk of relapse after dUCBT relative to that observed with single UCB grafts,27,28 to our knowledge there has been no other large analysis comparing dUCB and other HSC sources. As the number of dUCBT increases, registry studies may allow further analysis to better understand the low risk of relapse/enhanced graft-versus-leukemia. One possible explanation is simply the greater use of more mismatched grafts in the setting of dUCBT. Eapen et al7 and Rocha et al11 have previously shown lower risks of relapse in recipients of 2-antigen mismatched single UCB units relative to HLA matched marrow in children and 5-6/6 HLA matched UCBT, respectively. Whether each unit contributes to the graft-versus-leukemia effect independently is unknown. It is also possible that killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor-ligand mismatching after UCBT may be associated with reduced relapse risk. However, this remains controversial. While our data do not support an effect on the incidence of relapse,29 Willemze et al have observed an association between killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor-ligand mismatch and lower risk of relapse.30 Alternatively, the lower risk of relapse may reflect in vivo selection of the cord with the greater inherent immune reactivity. In the majority of dUCBT, only one cord ultimately engrafts eliminating the other via immunologic reactivity.31 This in vivo selection may explain both the greater antitumor effect seen with dUCBT compared with the use of single units, as well as the increased incidence of grade 2 acute GVHD in recipients of dUCB transplantation compared single unit recipients.32 While this analysis suggests that dUCBT may be associated with a reduced risk of relapse, the findings of this retrospective analysis must still be interpreted with caution.

As with single UCBT, the use of dUCB grafts is associated with a higher risk of NRM. The majority of nonrelapse deaths in dUCBT recipients occurred within the first 100 days with most deaths attributed to graft failure, infection and hemorrhage. As in other reports, hematopoietic recovery was delayed after dUCBT compared with adult donor types. Given the adverse influence of slow hematopoietic recovery on NRM, novel strategies that shorten the time to neutrophil recovery after dUCBT, such as Notch-mediated ex vivo expansion33 or mesenchymal stem cell–based ex vivo expansion,34 may reduce NRM and further improve outcomes. In addition, lower risks of grade 2-4 acute and chronic GVHD after dUCBT compared with MUD and MMD transplantation might be expected to reduce the risk of opportunistic infection and impaired quality of life.32

Ideally, a randomized study would be planned to verify these observations. However, there are logistical issues that will make this difficult. While dUCBT is available to most, other stem cell sources are restricted by HLA matching requirements in addition to inherent delays associated with donor testing and clearance. Until then, we are limited to multi center or registry reports. While registry based studies will likely have the advantage of larger numbers of patients, there is always the risk of heterogeneity in eligibility criteria, treatment plans and supportive care between transplant centers. Added uncertainties including the impact of peripheral blood (PB) or bone marrow (BM) as a graft source may also influence the interpretation of future analyses. Available registry-based data showed higher risk of GVHD for PB recipients, but similar survival for both BM and PB.26,35 Importantly, future studies comparing rates of immune recovery, risks of opportunistic infection, and other late effects, including quality of life, in recipients of the various HSC sources are needed.

In conclusion, we recommend that patients with hematologic malignancy who lack an available HLA MRD or MUD be considered for UCBT. In circumstances where an adequate single UCB unit is not available (defined in this study as a cell dose > 3.0 × 107 nucleated cells/kg), a dUCBT is a reasonable alternative. The remarkably low relapse risk after dUCBT is intriguing and requires further research to elucidate the underlying mechanism of this potential benefit.

Acknowledgments

We thank Pablo Rubinstein, MD, Director of the Placental Blood Program at the New York Blood Center, for having us consider the possibility of double umbilical cord blood transplantation and compelling us to move it forward as a new treatment that could potentially address the limitation of cell dose. We also thank Michael J. Franklin, MS (UM) for assistance in editing.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute CA65493 (C.G.B and J.E.W.) and CA18029 (F.R.A.), the Children's Cancer Research Fund (J.E.W., T.E.D., and M.R.V.), American Cancer Society Scholar Award RSG-08-181-01-LIB (M.R.V), and The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation Clinical Investigator Award CI-35-07 (C.D.).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: C.G.B. was involved in conception, design of analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the article, and final approval of the version to be published; J.A.G., D.J.W., A.E.W., T.A.G., M.R.V., and F.R.A. were involved in interpretation of data, critical revision for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published; T.E.D. was involved in conception, design and statistical analysis, and final approval of the version to be published; and J.E.W. and C.D. were involved in conception, design analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Claudio G. Brunstein, Department of Medicine, Mayo Mail Code 480, 420 Delaware St SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455; e-mail: bruns072@umn.edu.

References

- 1.Wagner JE, Rosenthal J, Sweetman R, et al. Successful transplantation of HLA-matched and HLA-mismatched umbilical cord blood from unrelated donors: analysis of engraftment and acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 1996;88(3):795–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtzberg J, Laughlin M, Graham ML, et al. Placental blood as a source of hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation into unrelated recipients. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(3):157–166. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199607183350303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laughlin MJ, Barker J, Bambach B, et al. Hematopoietic engraftment and survival in adult recipients of umbilical-cord blood from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(24):1815–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106143442402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laughlin MJ, Eapen M, Rubinstein P, et al. Outcomes after transplantation of cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(22):2265–2275. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rocha V, Labopin M, Sanz G, et al. Transplants of umbilical-cord blood or bone marrow from unrelated donors in adults with acute leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(22):2276–2285. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi S, Iseki T, Ooi J, et al. Single-institute comparative analysis of unrelated bone marrow transplantation and cord blood transplantation for adult patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2004;104(12):3813–3820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eapen M, Rubinstein P, Zhang MJ, et al. Outcomes of transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood and bone marrow in children with acute leukaemia: a comparison study. Lancet. 2007;369(9577):1947–1954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60915-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi S, Ooi J, Tomonari A, et al. Comparative single-institute analysis of cord blood transplantation from unrelated donors with bone marrow or peripheral blood stem-cell transplants from related donors in adult patients with hematologic malignancies after myeloablative conditioning regimen. Blood. 2007;109(3):1322–1330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-020172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atsuta Y, Suzuki R, Nagamura-Inoue T, et al. Disease-specific analyses of unrelated cord blood transplantation compared with unrelated bone marrow transplantation in adult patients with acute leukemia. Blood. 2009;113(8):1631–1638. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gluckman E, Rocha V, Boyer-Chammard A, et al. Outcome of cord-blood transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Eurocord Transplant Group and the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(6):373–381. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199708073370602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rocha V, Gluckman E. Improving outcomes of cord blood transplantation: HLA matching, cell dose and other graft- and transplantation-related factors. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(2):262–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinstein P, Carrier C, Scaradavou A, et al. Outcomes among 562 recipients of placental-blood transplants from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(22):1565–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811263392201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner JE, Barker JN, DeFor TE, et al. Transplantation of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood in 102 patients with malignant and nonmalignant diseases: influence of CD34 cell dose and HLA disparity on treatment-related mortality and survival. Blood. 2002;100(5):1611–1618. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker JN, Weisdorf DJ, DeFor TE, et al. Transplantation of 2 partially HLA-matched umbilical cord blood units to enhance engraftment in adults with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2005;105(3):1343–1347. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ballen KK, Spitzer TR, Yeap BY, et al. Double unrelated reduced-intensity umbilical cord blood transplantation in adults. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(1):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutman JA, Leisenring W, Appelbaum FR, Woolfrey AE, Delaney C. Low relapse without excessive transplant-related mortality following myeloablative cord blood transplantation for acute leukemia in complete remission: a matched cohort analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(9):1122–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponce D, Zheng J, Gonzales AM, et al. Disease-free survival after cord blood transplantation is not different to that after related or unrelated donor transplantation in patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2009;114:906. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15(6):825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin PJ, Weisdorf D, Przepiorka D, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: VI. Design of Clinical Trials Working Group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12(5):491–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin DY. Non-parametric inference for cumulative incidence functions in competing risks studies. Stat Med. 1997;16(8):901–910. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970430)16:8<901::aid-sim543>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Royal Stat Soc B. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snedecor G, Cochran W. Statistical Methods. 8th ed. Ames IA: Iowa State University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodrigues CA, Canals C, Brunstein C, et al. Comparison of outcomes after unrelated cord blood transplantation and matched unrelated donor RIC transplantation for lymphoid malignancies - A Eurocord-Netcord Group/Lymphoma Working Party and Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Study. Blood. 2009;114:276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eapen M, Rocha V, Sanz G, et al. Effect of graft source on unrelated donor haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation in adults with acute leukaemia: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(7):653–660. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70127-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodrigues CA, Sanz G, Brunstein CG, et al. Analysis of risk factors for outcomes after unrelated cord blood transplantation in adults with lymphoid malignancies: a study by the Eurocord-Netcord and lymphoma working party of the European group for blood and marrow transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(2):256–263. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verneris MR, Brunstein CG, Barker J, et al. Relapse risk after umbilical cord blood transplantation: enhanced graft-versus-leukemia effect in recipients of 2 units. Blood. 2009;114(19):4293–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunstein CG, Wagner JE, Weisdorf DJ, et al. Negative effect of KIR alloreactivity in recipients of umbilical cord blood transplant depends on transplantation conditioning intensity. Blood. 2009;113(22):5628–5634. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-197467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willemze R, Rodrigues CA, Labopin M, et al. KIR-ligand incompatibility in the graft-versus-host direction improves outcomes after umbilical cord blood transplantation for acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(3):492–500. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gutman JA, Turtle CJ, Manley TJ, et al. Single-unit dominance after double-unit umbilical cord blood transplantation coincides with a specific CD8+ T-cell response against the nonengrafted unit. Blood. 2010;115(4):757–765. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-228999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacMillan ML, Weisdorf DJ, Brunstein CG, et al. Acute graft-versus-host disease after unrelated donor umbilical cord blood transplantation: analysis of risk factors. Blood. 2009;113(11):2410–2415. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-163238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delaney C, Heimfeld S, Brashem-Stein C, Voorhies H, Manger RL, Bernstein ID. Notch-mediated expansion of human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid reconstitution. Nat Med. 2010;16(2):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nm.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson SN, Ng J, Niu T, et al. Superior ex vivo cord blood expansion following co-culture with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37(4):359–366. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eapen M, Logan BR, Confer DL, et al. Peripheral blood grafts from unrelated donors are associated with increased acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease without improved survival. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(12):1461–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]