Abstract

Background

Staphylococcus epidermidis has emerged as one of the most important nosocomial pathogens, mainly because of its ability to colonize implanted biomaterials by forming a biofilm. Extensive studies are focused on the molecular mechanisms involved in biofilm formation. The LytSR two-component regulatory system regulates autolysis and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. However, the role of LytSR played in S. epidermidis remained unknown.

Results

In the present study, we demonstrated that lytSR knock-out in S. epidermidis did not alter susceptibility to Triton X-100 induced autolysis. Quantitative murein hydrolase assay indicated that disruption of lytSR in S. epidermidis resulted in decreased activities of extracellular murein hydrolases, although zymogram showed no apparent differences in murein hydrolase patterns between S. epidermidis strain 1457 and its lytSR mutant. Compared to the wild-type counterpart, 1457ΔlytSR produced slightly more biofilm, with significantly decreased dead cells inside. Microarray analysis showed that lytSR mutation affected the transcription of 164 genes (123 genes were upregulated and 41 genes were downregulated). Specifically, genes encoding proteins responsible for protein synthesis, energy metabolism were downregulated, while genes involved in amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis, amino acid transporters were upregulated. Impaired ability to utilize pyruvate and reduced activity of arginine deiminase was observed in 1457ΔlytSR, which is consistent with the microarray data.

Conclusions

The preliminary results suggest that in S. epidermidis LytSR two-component system regulates extracellular murein hydrolase activity, bacterial cell death and pyruvate utilization. Based on the microarray data, it appears that lytSR inactivation induces a stringent response. In addition, LytSR may indirectly enhance biofilm formation by altering the metabolic status of the bacteria.

Background

Staphylococcus epidermidis is an opportunistic pathogen which normally inhabits human skin and mucous membranes, primarily infecting immunocompromised individuals or those with implanted biomaterials. The pathogenicity of S. epidermidis is mostly due to its ability to form a thick, multilayered biofilm on polymeric surfaces [1-3]. Treatment of S. epidermidis infection has become a troublesome problem as biofilm-associated bacteria exhibit enhanced resistance to antibiotics and to components of the innate host defences [4,5]. Among the Staphylococci, the other major human pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus, which causes infections ranging from cutaneous infections and food poisoning to life-threatening septicaemia. Aside from biofilm, S. aureus produce a large array of exotoxins and exoezymes [6].

Two-component regulatory systems (TCSs) play a pivotal role in bacterial adaptation, survival, and virulence by sensing changes in the external environment and modulating gene expression in response to a variety of stimuli [7-9]. Among the TCSs identified in the genomes of S. epidermidis, functions of LytSR are unknown, though in S. aureus LytSR has been demonstrated to play a role in bacterial autolysis and biofilm formation.

LytSR two-component regulatory system was firstly identified from the S. aureus genome. The lytS integration mutant of S. aureus strain NCTC 8325-4 exhibited a marked propensity to form aggregates in liquid culture and an increased rate of penicillin-and Triton X-100-induced lysis. In combination with subsequent zymographic analysis, it was suggested that LytSR is involved in either regulation of murein hydrolases gene expression or modulation of murein hydrolase activity [10]. Recently, Shrama et al. reported that a lytS knockout mutant of S. aureus strain UAMS-1 produced more adherent biofilm [11].

In search of genes regulated by LytSR in S. aureus, two additional open reading frames immediately downstream from lytS and lytR were identified and designated gene lrgA and lrgB, whose transcription was positively regulated by LytSR and the global regulators Agr and SarA. It was proposed that LrgA, and possibly LrgB, functions in a similar way to an antiholin, i.e., blocking murein hydrolases access to the substrate peptidoglycan [12]. Bayles et al. put forward the possibility that LrgAB exploits a molecular strategy, which is functionally analogous to that mediated by the eukaryotic Bcl-2 family of apoptosis regulatory proteins, to control bacterial programmed cell death [13,14]. Recent study suggested that LytSR regulatory system sense a collapse in membrane potential and then induce the transcription of the lrgAB operon [15].

Several TCSs of S. aureus, such as agr and arlRS, have been proven to affect biofilm formation, whereas little has been known in the case of S. epidermidis. In S. aureus and S. epidermidis, an agr mutant forms a significantly thicker biofilm. However, the agr regulons of the two species comprise different genes. Autolysin E (AtlE) which has been documented to mediate initial attachment of S. epidermidis to a polymer surface, overexpresses in an agr mutant, whereas the homologus Atl protein in S. aureus is not under agr control [16,17]. Previous studies have shown that arlS mutation in S. aureus enhanced biofilm formation on a polystyrene surface in a complex TSB medium [18]. However, an arlS knockout mutant of S. epidermidis generated by our laboratory displayed significantly reduced ability of biofilm formation [19], which suggest S. aureus and S. epidermidis adopt different strategies to regulate biofilm formation even though the genome of S. epidermidis is highly homologous to that of S. aureus [6].

Therefore, to investigate the role of LytSR in bacterial autolysis and biofilm development in S. epidermidis, 1457ΔlytSRstrain was constructed. The transcriptional profile of 1457ΔlytSR was subsequently analyzed by DNA microarray and related functions were examined.

Results

Construction of S. epidermidis 1457ΔlytSR and the complementation strain

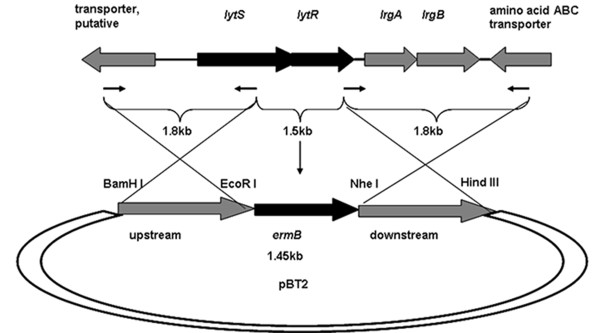

Because lytSR has been identified as a regulator of autolysis in S. aureus, we hypothesized that lytSR control the rate of autolysis in S. epidermidis, and may be related with biofilm formation. To test the possibility, lytSR knock-out strategy was applied. S. epidermidis 1457 was used in the present study. We firstly analyzed lytSR operon in S. epidermidis stains RP62A, ATCC12228, and 1457. The lytSR operon was amplified from S. epidermidis 1457 by PCR with the primers designed according to the S. epidermidis RP62A genome sequence, and shares more than 99% nucleotide identity with that in S. epidermidis strains RP62A and ATCC12228. BLAST searches indicated that the lytSR operon is extensively distributed in gram-positive bacteria. Immediately downstream of lytR locates the lrgAB operon predicted to encode two potential membrane associated proteins that are similar to bacteriophage holin proteins (Figure 1), as found in S. aureus [20].

Figure 1.

Physical map of the lytSR operon of S. epidermidis 1457 and construction of lytSR knockout mutant. Arrows depict open reading frames and indicate their orientations. lytSR operon were replaced with the erythromycin resistance gene (ermB) as indicated. The ermB gene and chromosomal regions flanking the corresponding deletions were amplified by PCR and cloned into plasmid pBT2, yielding the integration vectors pBT2-ΔlytSR. The crosses indicate the sites of homologous recombination.

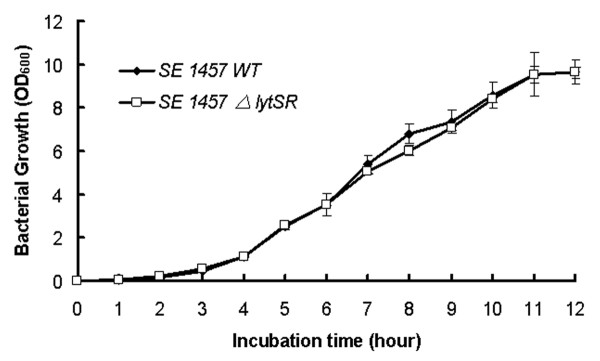

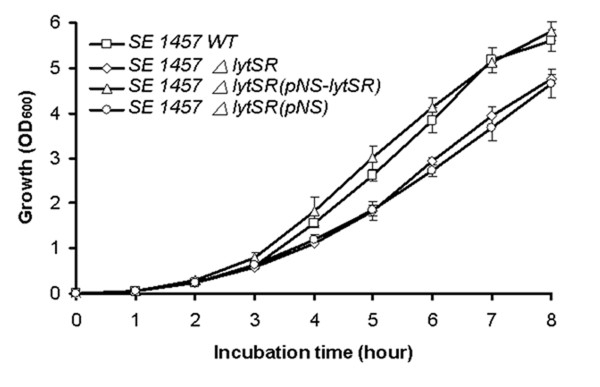

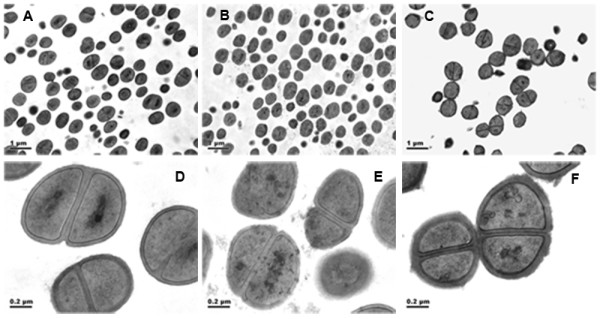

The lytSR knockout mutant of S. epidermidis 1457 was generated by allelic replacement, wherein the ermB gene replaced the predicted histidine kinase domain of lytS and lytR gene (Figure 1). The lytSR knockout mutant was then verified by direct PCR sequencing (Additional file 1, Figure S1) and biochemical tests (GPI Vitek card). To rule out an influence of second site mutations on the following findings, the complementation plasmid pNS-lytSR was constructed and then electroporated into the mutant, whereas introducing the empty vector pNS as a negative control. Deletion of lytSR did not result in a significant growth defect, indicating that lytSR is not essential for bacterial cell growth (Figure 2). The morphology of 1457ΔlytSR in stationary phase was observed with transmission electron microscope. It revealed that the cell surface was rough and diffused, suggesting alterations in its cell wall surface components (Figure 3). Except for diffused cell surface, the ΔatlE strain had a remarkably thickened cell wall (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Growth curves of S. epidermidis 1457ΔlytSR. Bacterial cultures were grown in TSB medium at 37 °C, and growth was monitored by measuring the turbidity of the cultures at 600 nm. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Morphology of S. epidermidis 1457ΔlytSR under transmission electron microscope. Strains of S. epidermidis 1457, ΔlytSR and ΔatlE were cultured in TSB till stationary phase, fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Thin sections were stained with 1% uranyl acetate-lead acetate and observed under a Philips Tecnai-12 Biotwin transmission electron microscope. A-C ×8,200 magnification of 1457, ΔlytSR and ΔatlE cells respectively; D-F ×43,000 magnification of 1457, ΔlytSR and ΔatlE cells respectively.

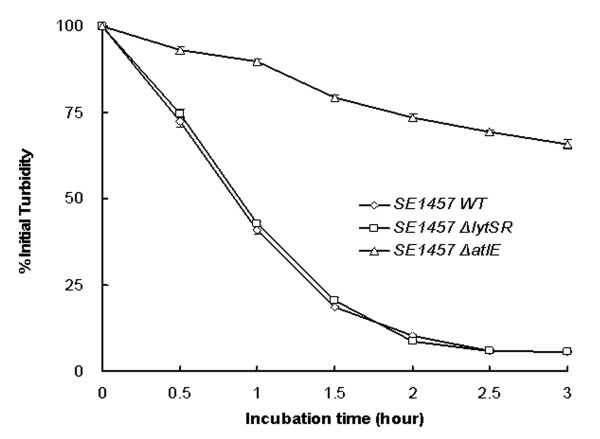

Modulation of lytSR on murein hydrolase activity

It has been reported that in S. aureus lytSR mutation increased susceptibility to Triton X-100 induced autolysis, therefore, we investigated effect of lytSR knockout on autolysis in S. epidermidis. Triton X-100 induced autolysis of bacterial cells was carried out, the atlE knockout mutant as a negative control. No difference was found between 1457ΔlytSR and its parent strain in the Triton X-100 induced autolysis, inconsistent with that observed in S. aureus [10], while the negative control atlE knockout mutant was resistant to autolysis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Autolysis assay of S. epidermidis 1457ΔlytSR. Bacterial cells were collected from early exponentially growing cultures (OD600 = 0.7) containing 1 M NaCl, washed twice with ice-cold water and resuspended in an equal volume of Tris-HCl(pH 7.2) containing 0.05%(vol/vol) Triton X-100. The rate of autolysis was measured as the decline in optical density. The atlE knockout mutant was used as a negative control. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

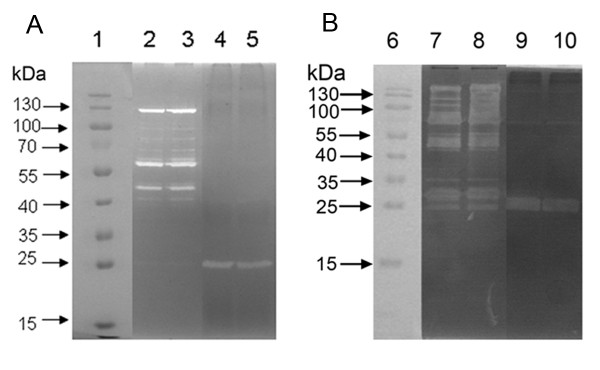

Given that the lytS mutation in S. aureus has pleiotropic effects on different murein hydrolase activity, zymographic analysis using SDS-PAGE incorporated with 2% w/v M. luteus (Figure 5A) or S. epidermidis (Figure 5B) cells was performed to analyze the activities of extracelluar and cell wall-associated murein hydrolases isolated from bacterial stationary-phase cultures. No significant difference was observed in the zymographic pattern of murein hydrolases between 1457ΔlytSR and the parent strain, regardless of M. luteus or S. epidermidis being taken as the main indicator.

Figure 5.

Zymographic analysis of S. epidermidis 1457ΔlytSR. Extracellular and cell surface proteins were isolated, and 30 μg of each was separated in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels containing 2.0 mg of M. luteus (A) or S. epidermidis (B) cells/ml. Murein hydrolase activity was detected by incubation overnight at 37 °C in a buffer containing Triton X-100, followed by staining with methylene blue. Lanes: 1 and 6, molecular mass marker; 2 and 7, cell wall protein from 1457ΔlytSR strain; 3 and 8, cell wall protein from wild type strain; 4 and 9, extracellular protein from 1457ΔlytSR strain; 5 and 10, extracellular protein from wild type strain. The results are representative of three independent experiments.

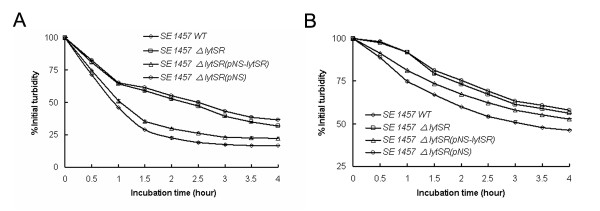

Quantitative murein hydrolase assay was further carried out by adding 100 μg of extracellular protein extract to a suspension of heat-killed M. luteus or S. epidermidis in Tris-HCl buffer, and monitoring the reduction in the suspension turbidity (OD600). However, cell wall hydrolysis performed with extracellular murein hydrolases from 1457ΔlytSRwas undergoing more slowly than that from the parent strain. After 4 hours' incubation, a decrease of 69% or 44% in turbidity (OD600) was observed in the suspension of M. luteus (Figure 6A) or S. epidermidis (Figure 6B) added with extracellular murein hydrolases from 1457ΔlytSR, contrasted to a reduction of 84% or 54% with extracellular murein hydrolases from the parent strain, indicating that disruption of lytSR resulted in decreased activities of extracellular murein hydrolases (Student's t test, P < 0.05) which probably could not be detected by zymographic analysis. Expression of lytSR in trans restored extracellular murein hydrolase activity to nearly wild-type levels (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Quantitative murein hydrolase assays of S. epidermidis 1457ΔlytSR. Aliquots (100 μg) of the extracellular proteins concentrated by ultrafiltration from the supernant were added to a 1-mg/ml suspension of M. luteus (A) and S. epidermidis (B) cells separately, and the turbidity at 600 nm was monitored for 4 h. Cell wall hydrolysis was determined by measurement of turbidity every 30 min. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

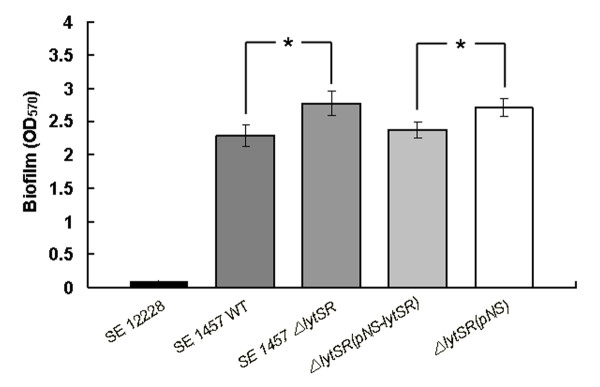

Impact of lytSR knockout on S. epidermidis biofilm formation

As biofilm formation is the major determinant of S.epidermidis pathogenicity, the impact of lytSR deletion on biofilm formation was further investigated. Semi-quantitative assay of S.epidermidis biofilm formation in polystyrene microtitre plates was performed and S.epidermidis ATCC12228 was used as a biofilm negative control. It was observed that 1457ΔlytSR produced slightly more biofilm than the wild-type counterpart (Student's t test, P < 0.05). When lytSR was complemented in the mutant, biofilm formation was reduced to the same levels as that observed in the parent strain (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Effect of lytSR gene knocking out on S. epidermidis biofilm formation. The biofilm formation of S. epidermidis ΔlytSR and its parent strain was detected by semi-quantitative microtiter plate assay. Briefly, the overnight bacterial were diluted by 1:200 and cultured in 96-well plate (200 μl/well) at 37 °C for 24 h. The well was washed by PBS for 3 times, fixed by 99% methanol and stained with crystal violet. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; ΔlytSR vs. WT; ΔlytSR(pNS-lytSR) vs. ΔlytSR(pNS-lytSR).

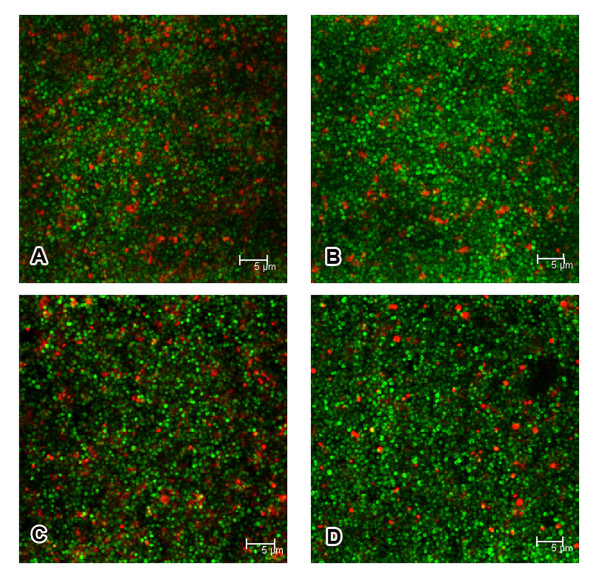

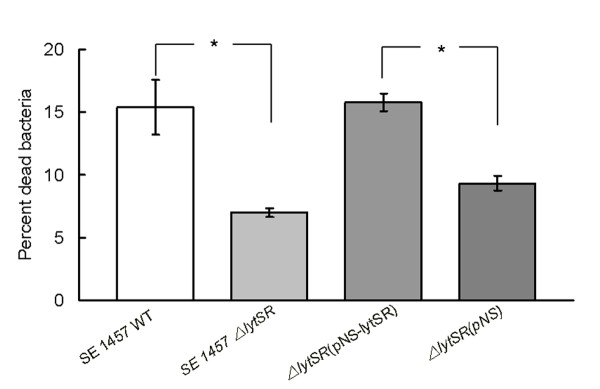

We further examined cell viability inside biofilm of 1457ΔlytSR and the wild-type strain by using a fluorescence-based Live/Dead staining method. With an appropriate mixture (1:1, m/m) of the SYTO 9 (green) and PI (red), bacteria with intact cell membranes were stained fluorescent green, whereas bacteria with damaged membranes were stained fluorescent red. Significantly decreased level of red fluorescence was observed inside biofilm of 1457ΔlytSR, comparing with that inside biofilm of the wild-type strain, as shown in Figure 8. Complementation of 1457ΔlytSR with plasmid pNS-lytSR restored the level of red fluorescence to that observed inside biofilm of the wild-type strain (Figure 8C, D). A quantitative method based on measuring the red/green fluorescence ratio was carried out to determine the relative cell viability inside biofilm. The percentage of dead cells inside 24-hour-old biofilms of 1457ΔlytSR and the wild-type strain were 6% and 15% respectively, as shown in Figure 9. Inside the biofilm of lytSR complementation strain, the percentage of dead cells was restored nearly to the wild-type level.

Figure 8.

Confocal photomicrographs of 24-hour-old biofilms. Biofilms containing S. epidermidis 1457 strains wild-type (A), ΔlytSR (B), ΔlytSR(pNS-lytSR) (C) and ΔlytSR(pNS) (D) were visualized by using the live/dead viability stain (SYTO9/PI). Green fluorescent cells are viable, whereas red fluorescent cells have a compromised cell membrane, as indicative of dead cells. Scale bars = 5 μm. The result is a stack of images at approximately 0.3 μm depth increments and represents one of the three experiments.

Figure 9.

Quantitative analysis of bacteria cell death in 24-hour-old biofilms. Live/dead stained biofilm cells were scraped from the dish and dispersed by pipetting. The integrated intensities of the green (535 nm) and red (625 nm) emission of suspensions excited at 485 nm were measured and the green/red fluorescence ratios (RatioR/G) were calculated. The percentage of dead cells inside biofilm was determined by comparison to the standard curve of RatioR/G versus percentage of dead cells. Data are means ± SEM of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; ΔlytSR vs. WT; ΔlytSR(pNS-lytSR) vs. ΔlytSR(pNS-lytSR).

Transcriptional profiling of 1457ΔlytSR strain

To investigate the regulatory role of LytSR, we used custom-made S. epidermidis GeneChips to perform a transcriptional profile analysis of the wild type and 1457ΔlytSR strains. Two criteria including 2-fold or greater change in expression level and P < 0.05 were employed to select the genes with significantly different expression. It was found that expression of 164 genes was affected by lytSR mutation, in which 123 were upregulated and 41 were downregulated. Transcription of lrgAB decreased drastically in 1457ΔlytSR, indicating that the operon was activated by LytSR in S.epidermidis, consistent with the finding for S. aureus. Further analysis of the microarray data showed that genes upregulated in the 1457ΔlytSR strain included these involved in purine biosynthesis (pur; SERP0651-SERP0657), amino acid biosynthesis (leu; SERP1668-SERP1671, hisF, argH, gltB) and membrane transport (oppC, modC, gltS, putP, SERP0284, SERP0340, etc.). Whereas, genes downregulated contained these involved in pyruvate metabolism (mqo-2, SERP2169 and mqo-3), anaerobic growth (nar; SERP1985-SERP1987, arc; SE0102-SE0106) (Table 1). In addition, genes responsible for encoding ribosomal proteins which make up the ribosomal subunits in conjunction with rRNA were found to be downregulated in 1457ΔlytSR (Table 1), consistent with that reported in transcriptional profiling studies of S. aureus by Sharma et al. [11]. Transcription of lrgAB decreased drastically in 1457ΔlytSR, indicating that the operon was activated by LytSR in S.epidermidis, consistent with the finding for S. aureus. We also noticed that expression of an AraC family transcriptional regulator homologue was remarkably higher in the mutant (Table 1). The microarray experiments were repeated by Prof. Jacques Schrenzel (Genomic Research Laboratory, University of Geneva Hospitals, Switzerland). Transcription of genes required for amino acid biosynthesis, carbon metabolism and membrane transport was also found to be altered in the mutant. Moreover, differential expression of general stress protein, alkaline shock protein 23 and cold shock protein was observed in the latter microarray data. Taken together, it suggested that LytSR may be involved in sensing and responding to changes in the metabolic state of the bacteria.

Table 1.

Genes expressed differentially in strain 1457ΔlytSR compared to the wild-type strain

| ORF | Gene name | Description or predicted function | Expression ratio (Mutant/WT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acid biosynthesis | |||

| SERP0034 | metE | 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate homocysteine methyltransferase | 2.096 |

| SERP0108 | gltB | glutamate synthase large subunit | 2.405 |

| SERP0548 | argH | argininosuccinate lyase | 5.03 |

| SERP1103 | aroK | shikimate kinase | 2.274 |

| SERP1668 | ilvC | ketol-acid reductoisomerase | 2.087 |

| SERP1669 | leuA | 2-isopropylmalate synthase | 2.344 |

| SERP1670 | leuB | 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase | 2.229 |

| SERP1671 | leuC | 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase small subunit | 11.45 |

| SERP2301 | hisF | imidazoleglycerol phosphate synthase, cyclase subunit | 5.429 |

| Amino acid transport | |||

| SERP0392 | di-tripeptide transporter, putative | 3.362 | |

| SERP0571 | oppC | oligopeptide transport system permease protein OppC | 12.38 |

| SERP0950 | peptide ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein, putative | 3.383 | |

| SERP1440 | putP | proline permease | 2.124 |

| SERP1935 | gltS | sodium:glutamate symporter | 3.267 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | |||

| SERP0284 | Na+/H+ antiporter, MnhD component, putative | 3.294 | |

| SERP0287 | Na+/H+ antiporter, MnhG component, putative | 2.576 | |

| SERP0660 | cobalt transport family protein | 2.718 | |

| SERP1777 | iron compound ABC transporter, iron | 2.383 | |

| SERP1859 | modC | molybdenum transport ATP-binding protein | 3.294 |

| SERP2428 | arsA | arsenical pump-driving ATPase | 3.274 |

| Protein synthesis | |||

| SERP0721 | pheS | Phe-tRNA synthetase alpha chain | 2.036 |

| SERP1809 | infA | translation initiation factor IF-1 | 0.5 |

| SERP1812 | rplO | ribosomal protein L15 | 0.482 |

| SERP1813 | rpmD | ribosomal protein L30 | 0.333 |

| SERP1814 | rpsE | 30 S ribosomal protein S5 | 0.37 |

| SERP1815 | rplR | 50 S ribosomal protein L18 | 0.323 |

| SERP1816 | rplF | 50 S ribosomal protein L6 | 0.332 |

| SERP1817 | rpsH | 30 S ribosomal protein S8 | 0.357 |

| SERP1818 | rpsN-2 | 30 S ribosomal protein S14 | 0.306 |

| SERP1819 | rplE | 50 S ribosomal protein L5 | 0.324 |

| SERP1821 | rplN | 50 S ribosomal protein L14 | 0.346 |

| SERP1820 | rplX | 50 S ribosomal protein L24 | 0.356 |

| SERP1822 | rpsQ | 30 S ribosomal protein S17 | 0.344 |

| SERP1823 | rpmC | 50 S ribosomal protein L29 | 0.332 |

| SERP1824 | rplP | 50 S ribosomal protein L16 | 0.438 |

| SERP1825 | rpsC | 30 S ribosomal protein S3 | 0.345 |

| SERP1826 | rplV | 50 S ribosomal protein L22 | 0.374 |

| SERP1827 | rpsS | 30 S ribosomal protein S19 | 0.385 |

| SERP1828 | rplB | 50 S ribosomal protein L2 | 0.421 |

| SERP1829 | rplW | 50 S ribosomal protein L23 | 0.424 |

| Nucleotide metabolism | |||

| SERP0070 | guaA | bifunctional GMP synthase/glutamine amidotransferase protein | 2.546 |

| SERP0651 | purC | phosphoribosylaminoimidazole-succinocarboxamide synthase | 2.036 |

| SERP0654 | purL | phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine synthetase | 2.341 |

| SERP0655 | purF | phosphoribosylpyrophosphate amidotransferase | 2.164 |

| SERP0656 | purM | phosphoribosylformylglycinamidine cyclo-ligase | 2.369 |

| SERP0657 | purN | IMP cyclohydrolase | 2.111 |

| SERP1003 | thyA-1 | thymidylate synthase | 2.014 |

| SERP1810 | adk | adenylate kinase | 0.444 |

| Energy metabolism | |||

| SE0102-12228 | carbamate kinase, putative | 0.259 | |

| SE0104-12228 | transcription regulator Crp/Fnr family protein | 0.343 | |

| SE0106-12228 | arcA | arginine deiminase | 0.301 |

| SERP0672 | cydA | cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit II-like protein | 13.85 |

| SERP1985 | narJ | nitrate reductase delta chain | 0.441 |

| SERP1986 | narH | nitrate reductase beta chain | 0.327 |

| SERP1987 | narG | nitrate reductase alpha chain | 0.324 |

| SERP1990 | nirB | nitrite reductase nitrite reductase | 0.354 |

| SERP2168 | mqo-2 | malate:quinone oxidoreductase | 0.317 |

| SERP2169 | hypothetical protein | 0.0165 | |

| SERP2261 | manA-2 | mannose-6-phosphate isomerase | 0.479 |

| SERP2312 | mqo-3 | malate:quinone oxidoreductase | 0.451 |

| SERP2352 | arcC | putative carbamate kinase | 0.427 |

| DNA replication, recombination and repair | |||

| SERP0558 | ISSep1-like transposase | 4.66 | |

| SERP0599 | site-specific recombinase, resolvase family | 2.352 | |

| SERP0892 | IS1272, transposase | 2.774 | |

| SERP0909 | lexA | SOS regulatory LexA protein | 2.227 |

| SERP1023 | DNA replication protein DnaD, putative | 2.049 | |

| SERP2474 | hsdR | type I restriction-modification system, R subunit | 46.79 |

| Transcriptional regulator | |||

| SERP0635 | transcriptional regulator, MarR family | 3.216 | |

| SERP1879 | transcriptional regulator, AraC family | 21.2 | |

* The entire list of differentially expressed genes can be found on the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ and is accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE20652

The altered expression of five of the genes identified by microarray analysis (lrgA, arcA, ebsB, leuC, SERP2169) in 1457ΔlytSR were confirmed by real-time RT-PCR with gyrB, a housekeeping gene, as the internal control, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Expression of genes regulated by LytSR confirmed by RT Real-time PCR

| Gene | Description | n-fold(microarray) | n-fold(Real time PCR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| lrgA | holin-like protein LrgA | 0.277 | 0.133 (0.124, 0.143) *** |

| SERP2169 | hypothetical protein | 0.0165 | 0.013 (0.008, 0.02) *** |

| arcA | arginine deiminase | 0.301 | 0.476 (0.377, 0.601) ** |

| ebsB | cell wall enzyme EbsB, putative | 0.091 | 0.278 (0.21, 0.369) ** |

| leuC | 3-isopropylmalate dehydratase small subunit | 11.45 | 3.85 (3.595, 4.124) ** |

* Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; ΔytSR1 vs. WT.

Pyruvate utilization of 1457 and 1457ΔlytSR

Ability of 1457ΔlytSRto utilize pyruvate was found to be impaired by using the Vitek GPI Card system. Meanwhile, expression of genes involved in pyruvate metabolism such as mqo-3, mqo-2 and its neighboring unknown gene SERP2169 were remarkably reduced. For examining the ability to utilize pyruvate, strains 1457 and 1457ΔlytSRwere cultured in pyruvate fermentation broth and bacterial growth was monitored. The 1457ΔlytSR displayed a significantly growth defect in pyruvate fermentation broth, whereas introducing plasmid pNS-lytSR into the mutant restored the phenotype, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Pyruvate utilization test of S. epidermidis 1457ΔlytSR. Bacteria were grown in pyruvate fermentation broth at 37 °C, and growth was monitored by measuring the turbidity of the cultures at 600 nm as described in Materials and Methods. Data are means ± SD of 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

The capacity of Staphylococci to produce a biofilm is determined by environmental factors, such as glucose, osmolarity, ethanol, temperature and anaerobiosis etc, which suggests that there is a mechanism that senses and responds to extracellular signals [21]. Two-component regulatory systems, composed of histidine kinases and their cognate response regulators, are the predominant means by which bacteria adapt to changes in their environment [7]. Previous studies have shown yycG/yycF two-component system is essential for cell viability in B. subtilis and S. aureus and positively controls biofilm formation [22-24]. Another two TCSs of S. aureus, agr and arlRS, have also been proven to regulate biofilm formation [16-18].

Seventeen pairs of TCSs have been determined in the genome of S. epidermidis ATCC35984 (RP62A), while 16 pairs in ATCC12228 [25]. We identified one pair of TCS encoding LytS and LytR homologs described in S. aureus [10]. The LytSR two-component system in S. aureus has been viewed as an important regulator of bacterial autolysis [20]. In the present study, the function of the S. epidermidis lytSR opreon was firstly investigated. The lytSR knockout mutation did not alter the susceptibility of strain 1457 to Triton X-100-induced lysis, which is different from the finding for S. aureus strain NCTC 8325-4 reported by Brunskill et al.[10]. Recently, they found that in the strain UAMS-1, lytS knock-out did not result in spontaneous and Triton X-100-induced lysis increasing [11]. The variation in susceptibility to Triton X-100-induced lysis between different staphylococcus strains could be explained partly by the fact that they represent different genetic background.

Since that lytS mutation in S. aureus has pleiotropic effects on different murein hydrolase activity [20], we hypothesized that in S. epidermidis, lytSR regulates murein hydrolase activity in a similar manner. Zymographic analysis revealed no significant differences between 1457ΔlytSR and the parent strain in the activities or expression of murein hydrolase isolated from both extracellular and cell wall fraction. However, quantification of the extracellular murein hydrolase activity produced by these strains demonstrated that 1457ΔlytSR produced diminished overall activity compared to that of the parental strain. As expected, microarray analysis revealed that lrgAB opreon was downregulated in 1457ΔlytSR. In S. aureus, LrgAB has a negative regulatory effect on extracellular murein hydrolase activity and disruption of lrgAB led to a significant increase in the activity [10,12]. cidAB operon, which encodes the holin-like counterpart of the lrgAB operon, and alsSD operon, which encodes proteins involved in acetoin production, were then identified. Mutation of either cidAB or alsSD operon in the S. aureus strain UAMS-1 caused a dramatic decrease in extracellular murein hydrolase activity [26,27]. We, therefore, speculate that in S. epidermidis some other LytSR regulated proteins similar to CidAB and/or AlsSD, may exist and overcome negative effect imposed by LrgAB on extracellular murein hydrolase activity, which warrants further investigation.

The role of cell death and lysis in bacterial adaptive responses to circumstances has been well elucidated in a number of bacteria, such as S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Webb et al. proposed that in P. aeruginosa cell death benefited a subpopulation of surviving cells and therefore facilitated subsequent biofilm differentiation and dispersal [28-30]. Moreover, genomic DNA released following bacterial lysis constitutes the skeleton of biofilm. Since LytSR positively regulates the activity of extracellular murein hydrolases, it may affect cell viability and function in biofilm formation. By using the CLSM, significant decrease in red fluorescence was observed inside biofilm of 1457ΔlytSR, which indicated reduced loss of cell viability. Quantitative analysis showed that the percentage of dead cells inside biofilm of the wild type strain was approximately two times higher than that in the mutant. The results are consistent with the observation that 1457ΔlytSR displayed a reduction in activity of extracellular murein hydrolases. Disruption of either cidA or alsSD genes on the S. aureus chromosome resulted in significantly decreased extracellular murein hydrolase activity compared with that of the parental strain, UAMS-1. Both the cidA and the alsSD mutant displayed reduced cell death in stationary phase and completely abrogated cell lysis relative to UAMS-1 [26,27]. Along these lines, the present study confirmed a connection between extracellular murein hydrolase activity and bacterial cell death. Furthermore, expression of cidC gene encoding pyruvate oxidase was found to be downregulated (5.07 fold) in 1457ΔlytSR through the microarray analysis. Deletion of cidC in S. aureus or S. pneumoniae caused reduced cell death and lysis in stationary phase[31,32]. Based on these data, it was suggested LytSR may play an important role in bacterial cell death and lysis inside biofilm.

In this study, 1457ΔlytSRwas found to have growth defect in pyruvate fermentation broth and introducing plasmid encoding LytSR (pNS-lytSR) into the mutant completely restored the phenotype. Based on the fact that the wild-type strain and the mutant grow equally well in TSB containing 0.25% glucose. As we know, glucose is catabolized by glycolysis to pyruvate. If 1457ΔlytSRis impaired in its ability to metabolize pyruvate, then this would be reflected in the growth curve in TSB medium. The data actually indicated that 1457ΔlytSRis impaired in the transport of pyruvate and probably amino acids. Previous studies regarding bacterial cells taking up carboxylic acid from the surrounding medium have shown that pyruvate is actively transported across the bacterial membrane and that proton motive force (PMF) plays an important role in the process [33]. In addition, transcription of genes involved in pyruvate metabolism such as mqo-3, mqo-2 and its neighbouring unknown gene SERP2169 were significantly downregulated in 1457ΔlytSR. These data along with the findings that in S. aureus LytSR responds to a collapse in Δψ by inducing the transcription of the lrgAB operon led us to hypothesize that LytSR accelerates pyruvate transport by sensing a reduction in PMF.

Compared to the parent stain, 1457ΔlytSRexhibited decreased expression of ribosomal genes and increased expression of amino acid biosynthetic genes, amino acyl-tRNA synthase genes, and amino acid transporters genes, which implies that lytSR mutation may induce a stringent response. Additionally, transcriptional profiling studies performed in Switzerland revealed that expression level of genes involved in stress response and cold shock was altered in the mutant. When bacteria encounter sudden unfavorable environment, protein synthesis will be inhibited, causing the induction or repression of many metabolic pathways according to physiological needs, and the induction of stationary-phase survival genes. This is called "the stringent response". Bacterial alarmone (p)ppGpp functions as a global regulator responsible for the stringent control. Two homologous (p)ppGpp synthetases, RelA and SpoT, have been identified and characterized in Escherichia coli [34-37]. Lemos et al. have reported that the relA mutation impaired the capacity of Streptococcus mutans to form biofilm[38]. No changes in transcription of the relA/spoT homolog(s) were found in 1457ΔlytSR. However, SERP1879 encoding an AraC family transcriptional regulator was found to be upregulated significantly in the mutant. Transcriptional regulators of the AraC family are widespread among bacteria and have three main regulatory functions in common: carbon metabolism, stress response, and pathogenesis[39,40].

Among the microarray data, several genes predicted to be involved in anaerobic metabolism were of particular interest. The arc operon encodes the enzymes of the arginine deiminase (ADI) pathway, which catalyzes the conversion of arginine into ornithine, ammonia, and CO2, with the concomitant production of 1 mol of ATP per mol of arginine consumed. In the absence of oxygen, the ADI pathway enables S. aureus to grow in the medium containing arginine [41]. Recent studies demonstrated that the arc operon identified in the genome of S epidermidis strain ATCC12228 but not in RP62A is located on a novel genomic island termed arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME). Except for the ACME-encoded arc operon, all S. epidermidis carry a native arc operon on the core chromosome. Diep et al. supposed that ACME-encoded gene products might confer survival advantage of S. aureus strain USA300 and other ACME-bearing staphylococci within the host, resulting in the widespread dissemination of bacterial progeny [42-44]. In the present study, arginine deiminase activity was performed as previously described [45,46] and 1457ΔlytSR exhibited a reduced enzyme activity (Additional file 2, Figure S2).

In the present study, 1457ΔlytSR produced slightly more biofilm than its parent strain. However, no genes that are involved in biofilm formation directly, such as ica operon encoding enzymes responsible for PIA synthesis, were identified in the transcriptional profile. It was observed that ica transcription level and PIA production were similar between 1457ΔlytSR and its parent strain. Both tricarboxylic acid cycle stress and anaerobic condition have been proven to induce PIA production and promotion of biofilm, suggesting that changes in the metabolic status can be sensed and regulate biofilm formation [47,48]. Moreover, the stringent response has also been demonstrated to affect biofilm formation[38]. It suggests that lytSR mutation may indirectly enhance biofilm formation by altering the metabolic status of S. epidermidis.

Conclusions

The present study suggests that in S. epidermidis the LytSR two-component regulatory system play an important role in controlling extracellular murein hydrolase activity and bacterial cell death but has limited effect on autolysis. The lytSR mutation invokes a stringent type transcriptional profile, moreover, enhances biofilm formation, which suggests LytSR may function to indirectly regulate biofilm formation by altering the metabolic status of the bacteria, particularly under conditions in which supply of nutrient and oxygen is limited, such as the conditions in biofilm.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth media

All the bacterial strains and plasmid used in the present study are listed in Table 3. E. coli were cultivated in Luria-Bertani broth (LB), whereas Staphylococcus were grown in B-Medium or Tryptic soy broth (TSB, Oxoid, Basingstoke, England). Unless otherwise stated, all bacterial cultures were incubated at 37 °C, and aerated at 220 rpm with a flask-to-medium ratio of 5:1. SYTO 9 and propidium iodide (PI) (Live_Dead reagents, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) were used at a concentration of 1 mM for staining live or dead bacteria in biofilms. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: erythromycin, 10 μg ml-1, chloramphenicol, 10 μg ml-1, ampicillin, 100 μg ml-1.

Table 3.

Bacterial Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. aureus RN4220 | Restriction-negative, intermediate host for plasmid transfer from E. coli to S. epidermidis | [54] |

| S. epidermidis | ||

| 1457 | Biofilm-positive laboratory strain | [55] |

| 1457 ΔlytSR | lytSR: : erm derivative of S. epidermidis 1457 | This study |

| 1457ΔlytSR (pNS-lytSR) | lytSR complementary strain | This study |

| 1457 ΔlytSR (pNS) | lytSR mutant containing the empty cloning vector | This study |

| 1457 ΔatlE | atlE: : erm derivative of S. epidermidis 1457 | [29] |

| 12228 | Biofilm-negative standard strain | [6] |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBT2 | Temperature-sensitive E. coli-Staphylococcus shuttle vector. Apr (E. coli) Cmr (Staphylococcus) | [49] |

| pEC1 | pBluescript KS+ derivative. Source of ermB gene (Emr). Apr | [49] |

| pBT2-ΔlytSR | Deletion vector for lytSR; ermB fragment flanked by fragments upstream and downstream of lytSR in pBT2 | This study |

| pNS | E. coli-Staphylococcus shuttle cloning vector. Apr (E. coli) Spcr (Staphylococcus) | This study |

| pNS-lytSR | Plasmid pNS containing lytSR fragment and its native promoter | This study |

*Abbreviations: Ap, ampicillin; Cm, chloramphenicol; Em, erythromycin; Spc, spectinomycin

Construction of the S. epidermidis lytSR knockout mutant

In S. epidermidis 1457 strain inactivation of the lytSR operon via homologous recombination using temperature sensitive shuttle vector pBT2 was carried out as described by Bruckner [49]. An XbaI/HindIII-digested erythromycin-resistance cassette (ermB) from plasmid pEC1 was inserted into the pBT2 plasmid, named as pBT2-ermB. The regions flanking lytSR operon amplified by PCR were then ligated into the plasmid pBT2-ermB. Primers for PCR were designed according to the genomic sequence of S. epidermidis RP62A (GenBank accession number CP000029). Sequences of the primers are listed in Table 4. The homologous recombinant plasmid, designated pBT2-ΔlytSR, was first transformed by electroporation into S. aureus RN4220 and then into S. epidermidis 1457. The recombinant strains were grown in B-Medium (10 μg Em ml-1) at 30 °C for 16 h, to late-stationary phase. Subsequently, three millilitres of the 30 °C culture was inoculated into 300 ml fresh B-Medium (1:100 dilution) containing 2.5 μg Em ml-1. Allele replacement of the temperature-sensitive pBT2-ΔlytSR was achieved following two rounds of growth at 42 °C for 24 h without antibiotic and subsequent selection of Em-resistant (2.5 μg Em ml-1) and Cm-sensitive (10 μg Cm ml-1) colonies on B-Medium agar plates. Successful replacement of the lytSR operon via homologous recombination and loss of the plasmid pBT2-ΔlytSR were verified by PCR and direct sequencing. For analysis of physiological and biochemical changes in the mutant, a GPI-vitek test system was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (BioMerieux Vitek, Hazelwood, Mo, USA).

Table 4.

Primers used in this study

| Primers | Sequence(5'→3')* | Restriction |

|---|---|---|

| Primers used for PCR products in allelic gene replacement | ||

| lyt-UF (upstream fragment) | CCGGAATTCGAACCGATGGACCAGTAG | BamHI |

| lyt-UR (upstream fragment) | CGGAATTCTAAAGAGGGACGACAATGG | EcoRI |

| lyt-DF (downstream fragment) | CCCAAGCTTCAACAACTCGGTCTTCAA | HindIII |

| lyt-DR (downstream fragment)) | CTAGCTAGCAAAGGTATGGGAATGACG | NheI |

| Primers used in complementation of 1457ΔytSR1 strain | ||

| lyt-CF | GGGGTACCTTATTGAAGACCGAGTTGTTGTTTA | BamHI |

| lyt-CR | CGGGATCCTATGAAACAAGCCAATGTAAGTGC | KpnI |

| Primers used for real time RT-PCR in confirmation of microarray data | ||

| gyrB-RF | TTTCACTTTCTTCAGGGTTCTTAC | |

| gyrB-RR | CCATCTGTAGGACGCATTATTG | |

| lrgA-RF | GCATTGTGAAATTAGGTCAAGTTG | |

| lrgA-RR | ACTAATAATTGTGACGCAAAGCC | |

| serp2169-RF | GCATCCGCTTCTCCAATATCTG | |

| serp2169-RR | TAAACAACATACACACGCTAAACC | |

| ebsB-RF | TTTGATGCTGCGACTAAAGG | |

| ebsB-RR | CATTGCTGCCCATTCTGC | |

| arcA-RF | GGCTGACTCATACATCTTGG | |

| arcA-RR | GGGTTGTGGTGACATACG | |

| leuC-RF | CCAGGATGTTCTATGTGCTTAGG | |

| leuC-RR | CGCCTTTGCCTTGTCTTCC | |

* Primers were designed according to the genomic sequence of S. epidermidis RP62A (GenBank accession number CP000029).

Complementation of 1457ΔlytSR with pNS-lytSR

For complementation of 1457ΔlytSR strain, the staphylococcus cloning vector pCN51 was modified by replacing the erythromycin-resistance cassette with the spectinomycin-resistance cassette, named as pNS [50]. The lytSR operon encompassing its promoter and ribosome binding site was amplified by PCR with primers lyt-CF and lyt-CR. The resulting PCR product was then ligated into BamHI and KpnI sites of the pNS vector. The recombinant plasmid allowed the expression of lytSR under the control of its native promoter, named as pNS-lytSR. The promoter sequences were predicted by using BDGP Neural Network Promoter Prediction software http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/promoter.html. Meantime, the empty vector pNS was electroporated into 1457ΔlytSRas a control.

Morphology of 1457ΔlytSR observed with transmission electron microscopy

Strains of S. epidermidis 1457, ΔlytSR and ΔatlE were cultured in TSB medium for 16 hours, and resuspended in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight. After postfixation in osmium tetroxide, the preparations were dehydrated with increasing alcohol concentrations and embedded in Epon 812. Thin sections were cut using a Leica Ultracut R at a thickness of 70 nm, stained with 1% uranyl acetate-lead acetate and examined with a Philips Tecnai-12 Biotwin transmission electron microscope.

Triton X-100 induced autolysis

To examine the potential role of lytSR in the regulation of autolysis in Staphylococcus epidermidis, Triton X-100-induced autolysis of 1457ΔlytSR was performed as described by Brunskill & Bayles [10]. Bacterial cells of 50 ml were collected from early exponentially growing cultures (OD600 = 0.7) containing 1 M NaCl, and the cells were pelleted by centrifugation. The cells were washed twice with 50 ml of ice-cold water and resuspended in 50 ml of Tris-HCl (pH 7.2) containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Autolysis was measured during incubation at 37 °C as the decrease in turbidity at 600 nm, using a model 6131 Biophotometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Zymogram

To determine if the lytSR mutation affects murein hydrolase activity, zymographic analysis of extracellular, cell wall-associated murein hydrolases from strains 1457 and 1457ΔlytSR grown in TSB medium was carried out essentially as described previously [12,51]. Cell-wall-associated murein hydrolases were extracted with 4% SDS. Briefly bacteria cells from overnight cultures were pelleted down, washed twice with 100 mM phosphate buffer and resuspended by 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer containing 4% SDS in amount about equal to wet weight of pellet. The cell suspension was incubated at 37 °C water bath for 10 min. The supernatant containing surface proteins were collected after centrifugation. Extracellular and cell surface proteins extracted were separated in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels containing 2.0 mg of M. luteus or S. epidermidis cells/ml. Murein hydrolase activity was detected by incubation overnight at 37 °C in a buffer containing Triton X-100, followed by staining with methylene blue.

Cell wall hydrolysis assays

To quantify the amount of hydrolysis observed in the zymographic analysis, cell wall hydrolysis assays were examined as described by Groicher et al. [12]. Extracellular murein hydrolases of bacteria were isolated from 15 ml of a 16-h culture by centrifugation at 6,000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was filter-sterilized and concentrated 100-fold using a Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter unit (Milipore, 5 kD). The concentration of total proteins in each preparation was determined using the Bradford assay according to the manufacturer's directions. Briefly, 100 μg of enzyme extract was added to a suspension of autoclaved and lyophilized M. luteus or S. epidermidis cells (1.0 mg/ml) in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and incubated at 37 °C with shaking. Cell wall hydrolysis was measured as decrease in turbidity at 600 nm every 30 min, using a model 6131 Biophotometer (Ependorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Detection of Biofilm formation

To investigate the ability of 1457ΔlytSR to form biofilm, the standard microtiter-plate test was carried out essentially as described by Christensen et al. [52]. Briefly, overnight cultures of S. epidermidis strains grown in TSB medium were diluted 1:200 and inoculated into wells of polystyrene microtiter plates (200 μl per well) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the wells were washed gently three times with 200 μl sterile PBS, air-dried and stained with 2% crystal violet for 5 min. Then, the plate was rinsed under running tap water, the crystal violet was redissolved in ethanol and the absorbance was determined at 570 nm.

To determine whether lytSR affects cell viability in biofilm, bacterial cells were cultivated in cover-glass cell-culture dish (WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA) as described previously [29]. Briefly, overnight cultures of S. epidermidis strains grown in TSB medium were diluted 1:200, then inoculated into the dish (2 ml per dish) and incubated at 37 °C. After 24 hours, the dish was washed gently three times with 1 ml sterile 0.85% NaCl, then stained by SYTO 9 and PI for 15 min and examined by Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope.

Quantitative analysis of bacterial cell death inside biofilms

To quantify relative viability of S. epidermidis strains, live/dead stained biofilms were scraped from the dish and dispersed thoroughly by pipetting. The integrated intensities (1 second) of the green (SYTO 9, 535 nm) and red (PI, 625 nm) emission of suspensions excited at 485 nm were measured respectively by Beckman Coulter DTX880 multimode detectors. The red/green fluorescence ratios (RatioR/G) were calculated, and a standard curve of Ratio R/G versus percentage of dead cells in the S. epidermidis suspension was plotted as described in the manuals of LIVE/DEAD® BacLight™Bacterial Viability Kit L7012 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA). The percentage of dead cells inside biofilms was determined by comparison to the standard curve.

Pyruvate utilization test

To verify physiological changes of 1457ΔlytSR detected by GPI-vitek test system, overnight cultures of S. epidermidis were diluted 1:200 into Pyruvate fermentation broth (Tryptone 10 g, Pyruvate 10 g, Yeast extract 5 g, Dipotassium phosphate 5 g, Sodium chloride 5 g per liter, pH 7.4) and incubated microaerobically at 37 °C [53]. The growth was detected by monitoring turbidity of the cultures at 600 nm.

RNA extraction and Microarray analysis

Overnight cultures of S. epidermidis 1457 and 1457ΔlytSR were diluted 1:200 into fresh TSB and grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 3.0 (mid-exponential growth). Eight millilitres of bacterial cultures were pelleted, washed with ice-cold saline, and then homogenized using 0.1 mm Ziconia-silica beads in Mini-Beadbeater (Biospec) at a speed of 4800 rpm. The bacterial RNA was isolated using a QIAGEN RNeasy kit according to the standard QIAGEN RNeasy protocol.

The custom-made S. epidermidis GeneChips (Shanghai Biochip Co., Ltd) included qualifiers representing open reading frame (ORF) sequences identified in the genomes of the S. epidermidis strain RP62A, as well as unique ORFs in S. epidermidis strain 12228. The GeneChips were composed of cDNA array containing PCR products of 2316 genes and oligonucleotide array containing 252 genes. Reverse transcription were performed using 2 μg of total RNA using T7 promoter primers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and then cRNA was transcribed from the resulting cDNA as template. cRNA prepared form 1457ΔlytSR and the parent strain was labelled using the dyes Cy3 and Cy5 according to the manufacturer's instructions(Amersham, Piscataway, New Jersey) respectively. Microarray hybridization (at 42 °C for 16 h) and washing of the slides at 50 °C were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Hybridized slides were scanned by Agilent Scanner (G2655AA) at a 10-μm resolution. Data of each image were normalized to the mean ratio of means of all features. Mean values and standard deviations of gene expression ratios based on three spot replicates on each microarray were calculated in Microsoft Excel XP. The complete set of microarray data was deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ and is accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE20652.

Validation of microarray data by Real time PCR

To confirm the results of the microarray data, the relative expression levels of the lrgA, ebsB, arcA, serp2169 and leuC genes were determined by real-time PCR with gene-specific primers, designed according to the genomic sequence of S. epidermidis RP62A (GenBank accession number CP000029). The sequences of the primers are shown in Table 4. Briefly, DNase-treated RNA was reverse transcribed using M-MLV and a hexamer random primer mix. Appropriate concentration of cDNA sample was then used for real-time PCR using an ABI 7500 real-time PCR detection system, gene-specific primers, and the SYBR Green I mixture (Takara, Dalian, China). Relative expression levels were determined by comparison to the level of gyrB expression in the same cDNA preparations.

Statistical analysis

Experimental data obtained were analyzed with the SPSS software and compared by Student's t test. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TZ performed most of the experimental work and drafted the manuscript. QL carried out real time RT-PCR experiments. JH and FY participated in microarray analysis and corrected the manuscript. DQ and YW directed the project and analyzed data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Validation of S. epidermidis 1457 ΔlytSR strain by PCR analysis.

Figure S2. Arginine deiminase activity assays for S. epidermidis.

Contributor Information

Tao Zhu, Email: 071101036@fudan.edu.cn.

Qiang Lou, Email: 071101038@fudan.edu.cn.

Yang Wu, Email: yangwu@fudan.edu.cn.

Jian Hu, Email: hobbyhujian@sina.com.

Fangyou Yu, Email: yfy1972919@163.com.

Di Qu, Email: dqu@fudan.edu.cn.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Patrice Francois (Genomic Research Laboratory, University of Geneva Hospitals, Switzerland) for repeating the microarray experiments.

This work was supported by the 11th Five-Year Plan of the Ministry of Sciences and Technology (2010DFA32100, 2009ZX09303-005, 2008ZX10003-016), the Hi-Tech Program of China (863) (2006AA02A253), the Scientific Technology Development Foundation of Shanghai (08JC1401600, 10410700600), National Natural Science Foundation of China (30800036), the Research Initiation Grant for Young Faculty of Fudan University (09FQ43).

References

- Ziebuhr W, Heilmann C, Gotz F, Meyer P, Wilms K, Straube E, Hacker J. Detection of the intercellular adhesion gene cluster (ica) and phase variation in Staphylococcus epidermidis blood culture strains and mucosal isolates. Infection and immunity. 1997;65(3):890–896. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.890-896.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp ME, Archer GL. Coagulase-negative staphylococci: pathogens associated with medical progress. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19(2):231–243; quiz 244-235. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden MG, Chen W, Singvall J, Xu Y, Peacock SJ, Valtulina V, Speziale P, Hook M. Identification and preliminary characterization of cell-wall-anchored proteins of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2005;151(Pt 5):1453–1464. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong C, Kocianova S, Voyich JM, Yao Y, Fischer ER, DeLeo FR, Otto M. A crucial role for exopolysaccharide modification in bacterial biofilm formation, immune evasion, and virulence. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279(52):54881–54886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: survival mechanisms of clinically relevant microorganisms. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2002;15(2):167–193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YQ, Ren SX, Li HL, Wang YX, Fu G, Yang J, Qin ZQ, Miao YG, Wang WY, Chen RS. et al. Genome-based analysis of virulence genes in a non-biofilm-forming Staphylococcus epidermidis strain (ATCC 12228) Molecular microbiology. 2003;49(6):1577–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annual review of biochemistry. 2000;69:183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skerker JM, Prasol MS, Perchuk BS, Biondi EG, Laub MT. Two-component signal transduction pathways regulating growth and cell cycle progression in a bacterium: a system-level analysis. PLoS biology. 2005;3(10):e334.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader MW, Sanowar S, Daley ME, Schneider AR, Cho U, Xu W, Klevit RE, Le Moual H, Miller SI. Recognition of antimicrobial peptides by a bacterial sensor kinase. Cell. 2005;122(3):461–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill EW, Bayles KW. Identification and molecular characterization of a putative regulatory locus that affects autolysis in Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of bacteriology. 1996;178(3):611–618. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.611-618.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma Kuinkel BK, Mann EE, Ahn JS, Kuechenmeister LJ, Dunman PM, Bayles KW. The Staphylococcus aureus LytSR two-component regulatory system affects biofilm formation. Journal of bacteriology. 2009;191(15):4767–4775. doi: 10.1128/JB.00348-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groicher KH, Firek BA, Fujimoto DF, Bayles KW. The Staphylococcus aureus lrgAB operon modulates murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. Journal of bacteriology. 2000;182(7):1794–1801. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.7.1794-1801.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayles KW. Are the molecular strategies that control apoptosis conserved in bacteria? Trends in microbiology. 2003;11(7):306–311. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(03)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KC, Bayles KW. Death's toolbox: examining the molecular components of bacterial programmed cell death. Molecular microbiology. 2003;50(3):729–738. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.t01-1-03720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton TG, Yang SJ, Bayles KW. The role of proton motive force in expression of the Staphylococcus aureus cid and lrg operons. Molecular microbiology. 2006;59(5):1395–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong KF, Vuong C, Otto M. Staphylococcus quorum sensing in biofilm formation and infection. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296(2-3):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles BR, Horswill AR. Agr-mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4(4):e1000052.. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Arana A, Merino N, Vergara-Irigaray M, Debarbouille M, Penades JR, Lasa I. Staphylococcus aureus develops an alternative, ica-independent biofilm in the absence of the arlRS two-component system. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187(15):5318–5329. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5318-5329.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Zhu T, Lou Q, Wu Y, Han C, Qu D. Biological functions of arlS gene of two-component signal transduction system in Staphylococcus epidermids. Chinese Journal of Microbiology and Immunology. 2007;27(10):.. [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill EW, Bayles KW. Identification of LytSR-regulated genes from Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of bacteriology. 1996;178(19):5810–5812. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5810-5812.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim Y, Jana M, Luong TT, Lee CY. Control of glucose-and NaCl-induced biofilm formation by rbf in Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of bacteriology. 2004;186(3):722–729. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.722-729.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell A, Dubrac S, Andersen KK, Noone D, Fert J, Msadek T, Devine K. Genes controlled by the essential YycG/YycF two-component system of Bacillus subtilis revealed through a novel hybrid regulator approach. Molecular microbiology. 2003;49(6):1639–1655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabret C, Hoch JA. A two-component signal transduction system essential for growth of Bacillus subtilis: implications for anti-infective therapy. Journal of bacteriology. 1998;180(23):6375–6383. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6375-6383.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubrac S, Boneca IG, Poupel O, Msadek T. New insights into the WalK/WalR (YycG/YycF) essential signal transduction pathway reveal a major role in controlling cell wall metabolism and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189(22):8257–8269. doi: 10.1128/JB.00645-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z, Zhong Y, Zhang J, He Y, Wu Y, Jiang J, Chen J, Luo X, Qu D. Bioinformatics analysis of two-component regulatory systems in Staphylococcus epidermidis. CHINESE SCIENCE BULLETIN. 2004;49(12):1267–1271. doi: 10.1360/03wc0384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KC, Firek BA, Nelson JB, Yang SJ, Patton TG, Bayles KW. The Staphylococcus aureus cidAB operon: evaluation of its role in regulation of murein hydrolase activity and penicillin tolerance. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185(8):2635–2643. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.8.2635-2643.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SJ, Dunman PM, Projan SJ, Bayles KW. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus CidR regulon: elucidation of a novel role for acetoin metabolism in cell death and lysis. Molecular microbiology. 2006;60(2):458–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb JS, Thompson LS, James S, Charlton T, Tolker-Nielsen T, Koch B, Givskov M, Kjelleberg S. Cell death in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Journal of bacteriology. 2003;185(15):4585–4592. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.15.4585-4592.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z, Ou Y, Yang L, Zhu Y, Tolker-Nielsen T, Molin S, Qu D. Role of autolysin-mediated DNA release in biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Microbiology (Reading, England) 2007;153(Pt 7):2083–2092. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KC, Mann EE, Endres JL, Weiss EC, Cassat JE, Smeltzer MS, Bayles KW. The cidA murein hydrolase regulator contributes to DNA release and biofilm development in Staphylococcus aureus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(19):8113–8118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610226104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regev-Yochay G, Trzcinski K, Thompson CM, Lipsitch M, Malley R. SpxB is a suicide gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae and confers a selective advantage in an in vivo competitive colonization model. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189(18):6532–6539. doi: 10.1128/JB.00813-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton TG, Rice KC, Foster MK, Bayles KW. The Staphylococcus aureus cidC gene encodes a pyruvate oxidase that affects acetate metabolism and cell death in stationary phase. Molecular microbiology. 2005;56(6):1664–1674. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsau J-L, Guffanti AA, Montville TJ. Pyruvate is transported by a proton symport inLactobacillus plantarum 8014. Current Microbiology. 1992;25(1):47–50. doi: 10.1007/BF01570082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger S, Dror IB, Aizenman E, Schreiber G, Toone M, Friesen JD, Cashel M, Glaser G. The nucleotide sequence and characterization of the relA gene of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(30):15699–15704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarubbi E, Rudd KE, Xiao H, Ikehara K, Kalman M, Cashel M. Characterization of the spoT gene of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(25):15074–15082. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashel M, Gentry DR, Hernandez VJ, D V. In: Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and molecular biology. Neidhardt FC, editor. Vol. 1. ASM Press; 1996. The stringent response; pp. 1458–1496. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos JA, Brown TA Jr, Burne RA. Effects of RelA on key virulence properties of planktonic and biofilm populations of Streptococcus mutans. Infection and immunity. 2004;72(3):1431–1440. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1431-1440.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frota CC, Papavinasasundaram KG, Davis EO, Colston MJ. The AraC family transcriptional regulator Rv1931c plays a role in the virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection and immunity. 2004;72(9):5483–5486. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5483-5486.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallegos MT, Schleif R, Bairoch A, Hofmann K, Ramos JL. Arac/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61(4):393–410. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.393-410.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhlin J, Kofman T, Borovok I, Kohler C, Engelmann S, Cohen G, Aharonowitz Y. Staphylococcus aureus ArcR controls expression of the arginine deiminase operon. Journal of bacteriology. 2007;189(16):5976–5986. doi: 10.1128/JB.00592-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep BA, Stone GG, Basuino L, Graber CJ, Miller A, des Etages SA, Jones A, Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Perdreau-Remington F, Sensabaugh GF. et al. The arginine catabolic mobile element and staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec linkage: convergence of virulence and resistance in the USA300 clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2008;197(11):1523–1530. doi: 10.1086/587907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, Phan TH, Chen JH, Davidson MG, Lin F, Lin J, Carleton HA, Mongodin EF. et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367(9512):731–739. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miragaia M, de Lencastre H, Perdreau-Remington F, Chambers HF, Higashi J, Sullam PM, Lin J, Wong KI, King KA, Otto M. et al. Genetic diversity of arginine catabolic mobile element in Staphylococcus epidermidis. PloS one. 2009;4(11):e7722.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara K, Yoshizawa Y, Tzeng S, Epstein WL, Fukuyama K. Colorimetric determination of citrulline residues in proteins. Analytical biochemistry. 1998;265(1):92–96. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Weiss EC, Otto M, Fey PD, Smeltzer MS, Somerville GA. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm metabolism and the influence of arginine on polysaccharide intercellular adhesin synthesis, biofilm formation, and pathogenesis. Infection and immunity. 2007;75(9):4219–4226. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00509-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong C, Kidder JB, Jacobson ER, Otto M, Proctor RA, Somerville GA. Staphylococcus epidermidis polysaccharide intercellular adhesin production significantly increases during tricarboxylic acid cycle stress. Journal of bacteriology. 2005;187(9):2967–2973. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.9.2967-2973.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramton SE, Ulrich M, Gotz F, Doring G. Anaerobic conditions induce expression of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infection and immunity. 2001;69(6):4079–4085. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.4079-4085.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckner R. Gene replacement in Staphylococcus carnosus and Staphylococcus xylosus. FEMS microbiology letters. 1997;151(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00116-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier E, Anton AI, Barry P, Alfonso B, Fang Y, Novick RP. Novel cassette-based shuttle vector system for gram-positive bacteria. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2004;70(10):6076–6085. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6076-6085.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann C, Hussain M, Peters G, Gotz F. Evidence for autolysin-mediated primary attachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis to a polystyrene surface. Molecular microbiology. 1997;24(5):1013–1024. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4101774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Younger JJ, Baddour LM, Barrett FF, Melton DM, Beachey EH. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1985;22(6):996–1006. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.6.996-1006.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross KC, Houghton MP, Senterfit LB. Presumptive speciation of Streptococcus bovis and other group D streptococci from human sources by using arginine and pyruvate tests. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1975;1(1):54–60. doi: 10.1128/jcm.1.1.54-60.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreiswirth BN, Lofdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305(5936):709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack D, Siemssen N, Laufs R. Parallel induction by glucose of adherence and a polysaccharide antigen specific for plastic-adherent Staphylococcus epidermidis: evidence for functional relation to intercellular adhesion. Infection and immunity. 1992;60(5):2048–2057. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.5.2048-2057.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Validation of S. epidermidis 1457 ΔlytSR strain by PCR analysis.

Figure S2. Arginine deiminase activity assays for S. epidermidis.