Abstract

Uptake of microorganisms by professional phagocytic cells leads to formation of a new subcellular compartment, the phagosome, which matures by sequential fusion with early and late endocytic compartments, resulting in oxidative and nonoxidative killing of the enclosed microbe. Few tools are available to study membrane fusion between phagocytic and late endocytic compartments in general and with pathogen-containing phagosomes in particular. We have developed and applied a fluorescence microscopy assay to study fusion of microbe-containing phagosomes with different-aged endocytic compartments in vitro. This revealed that fusion of phagosomes containing nonpathogenic Escherichia coli with lysosomes requires Rab7 and SNARE proteins but not organelle acidification. In vitro fusion experiments with phagosomes containing pathogenic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium indicated that reduced fusion of these phagosomes with early and late endocytic compartments was independent of endosome and cytosol sources and, hence, a consequence of altered phagosome quality.

Keywords: latex beads, phagocytosis, macrophage, phagolysosome, vacuole

Phagocytosis is the receptor-mediated ingestion of large particles, usually by professional phagocytes, i.e., neutrophils, dendritic cells, monocytes, or macrophages, resulting in formation of a new cytoplasmic compartment, the phagosome (1).

The development of a phagosome into a fully degradative phagolysosome is temporally and spatially ordered in that the newly formed “early” phagosome matures vectorially into a “late” phagosome after fusion with late endosomes and finally into a phagolysosome by fusion with lysosomes (1). This process is accompanied by loss of early endocytic markers [e.g., transferrin receptor (TfR), Rab5] and acquisition of late endocytic markers [e.g., lysosome associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), cathepsin D, Rab7] (1, 2). Fusion yield (fusion events per time period per organelle) generally decreases with endosome or phagosome age (2, 3). Rab GTPases and SNARE proteins are key regulators of all vesicle fusion events in the endocytic pathway. Rab proteins, in concert with tethering factors, specifically bridge membranes to be fused (4) with Rab5 supporting early (3, 5) and Rab7 supporting late (6) fusion events, but additional Rabs may be involved (7). SNARE proteins on both partner membranes are downstream effectors of Rab proteins and drive membrane fusion by formation of intermembrane quarternary SNARE complexes (8) composed of one R-SNARE helix from one partner membrane and Qa-, Qb-, and Qc-SNARE helices from the other. Following membrane fusion, quarternary SNARE complexes are disassembled under ATP hydrolysis by the N-ethylmaleimide sensitive factor (NSF) reforming activated SNAREs (8).

Several intracellular pathogens interfere with maturation of their phagosomes into fully degradative compartments, e.g., by disconnection of the phagosome from the endocytic pathway (e.g., Legionella pneumophilae) or by the arrest of phagosome maturation at a prelysosome stage (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis) (1). Macrophage phagosomes containing Salmonella enterica (SCP) acidify (9) and acquire LAMP1 but exclude mannose 6-phosphate receptor (10). Whereas several groups observed reduced fusion of SCPs with lysosomes compared to phagosomes containing inert particles (10–12), others did not (13). Fusogenicity of SCPs with other endocytic organelles in macrophages has been investigated little (10).

To truly understand the (dys)function of phagosome maturation at a molecular level, the fusion of endocytic with microbe-containing phagocytic organelles ought to be investigated in reconstituted systems, yet most published assays used bead-containing but not microbe-containing phagosomes (3, 5) and were limited to fusion of early phagosomes with early endocytic organelles (14, 15). Fusion of lysosomes with microbe-containing phagosomes has been reconstituted only in permeabilized macrophages (16). Here, we present a generally applicable in vitro assay to quantify fusion of phagosomes containing pathogenic or harmless microorganisms or inert particles with endocytic organelles of different maturation stages.

Results

Maturation of Phagosomes Containing Heat-Killed Escherichia coli DH5α or Latex Beads in Vivo.

Kinetic analysis of phagolysosome formation in J774E macrophages using fluorescently labeled, heat-killed, IgG-opsonized E. coli showed that colocalization of bacteria with preloaded lysosomal dye was almost quantitative after 30 min at 37 °C (Fig. S1 and SI Text). Therefore “30-min phagosomes” (phagolysosomes) were used in fusion experiments. Phagosomes containing IgG-coupled latex beads prepared after 30-min infection and 60-min chase were enriched in LAMP1 but not TfR (Fig. S2A). At this time point 84% (SD ± 4, n = 3) of beads colocalized with preloaded lysosomal dye.

Preparation of Endocytic Vesicles.

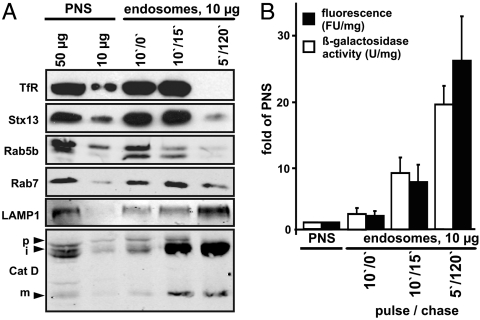

Using pulse/chase protocols for ferrofluid (10-nm paramagnetic particles) (17), different-aged endocytic compartments were purified from postnuclear supernatants (PNSs) and analyzed biochemically (Fig. 1 and SI Text). Compared with PNSs, 10′/0′ (pulse/chase) endosomes were strongly enriched in early endocytic TfR and Syntaxin 13 (Stx13), yet contained little late endocytic LAMP1 or mature cathepsin D. Both Rab5 and Rab7 were enriched and, on a single-organelle level, 50% of endosomes were positive for both Rabs (Fig. S3 and SI Text). 10′/15′ endosomes were also enriched in TfR and Stx13, but showed more late endosome characteristics, such as loss of Rab5, with only modest enrichment of lysosomal BSA rhodamine and lysosomal acid β-galactosidase activity. Lysosomes (5′/120′) were strongly enriched in LAMP1, cathepsin D, acid β-galactosidase activity, and BSA rhodamine (Fig. 1 A and B) and lacked early endocytic markers.

Fig. 1.

Preparation of endocytic vesicles. Macrophages were incubated with ferrofluid and magnetic compartments were isolated from a PNS. (A) Western blot analysis of PNS and purified endocytic compartments. Fifty or 10 μg protein of PNS, 10 μg protein for each purified fraction were added. Pulse/chase times for ferrofluid are indicated. Arrowheads indicate the positions of cathepsin D (Cat D) precursor (p), intermediate (i), and mature (m) forms. (B) Quantification of specific lysosomal acid β-galactosidase activities (U/mg) and of fluorescence (FU) of lysosomal BSA rhodamine. Shown are means and standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Characterization of Phagosome–Lysosome Fusion in Vitro.

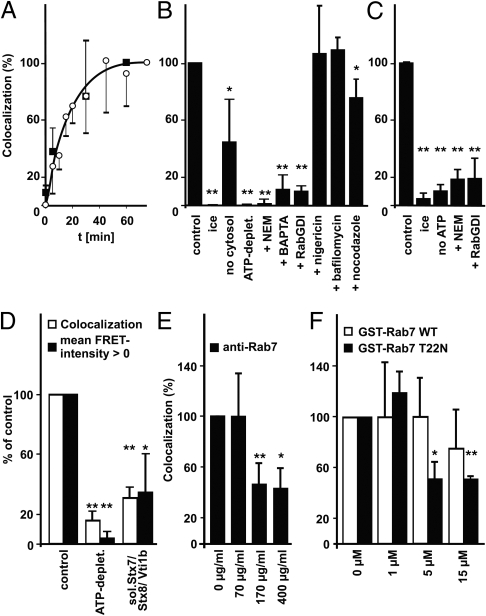

Cell-free fusion of E. coli-containing phagolysosomes (ECPs) with lysosomes (Fig. 2) progressed quickly and reached a plateau after approximately 40 min (Fig. 3A). In vitro fusion required physiological temperature and ATP, it was partly dependent on cytosol, was inhibited by the fast Ca2+ chelator 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N′,N′,N′,N′-tetraacetate (BAPTA), the NSF inhibitor N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), and by recombinant Rab guanosine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor (RabGDI), which can extract Rab(GDP) proteins from membranes (Fig. 3B). Fusion was sensitive to the calmodulin inhibitors trifluoperazine and W7, but not to W5, which has lower affinity for calmodulin (Fig. S4). These data agree with results from other in vitro fusion reactions (18–23). Neither bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of the vATPase, nor nigericin, a K+/H+ antiporter and proton gradient uncoupler, inhibited ECP-lysosome fusion in vitro, although either drug effectively collapsed lysosome pH gradients in vitro (SI Text and Fig. S5). Nocodazole inhibited ECP-lysosome fusion in vitro to a minor degree (Fig. 3B).

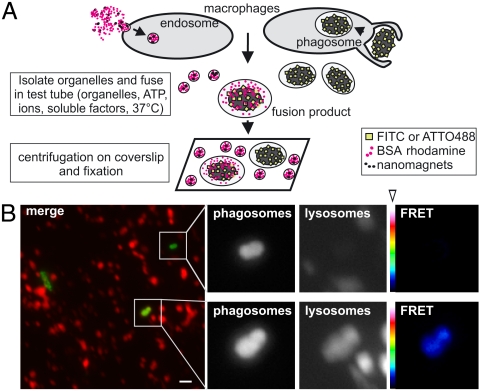

Fig. 2.

Assay for cell-free phagosome–endosome fusion. (A) Schematic representation of the cell-free phagosome–endosome fusion assay. See text for details. (B) Micrograph showing a representative image section of an in vitro ECP-lysosome fusion reaction prepared for fluorescence microscopy. In the overlay, phagosomes containing E. coli are shown in green, lysosomes in red. Enlargements show bacteria not colocalizing with lysosomal fluor (Upper) or colocalizing with lysosomal fluor (Lower). (Right) False color-coded (open arrowhead) images of FRET intensity for each pixel (black: low intensity; white: high intensity). Bar: 2 μM.

Fig. 3.

In vitro fusion of ECPs or LBPs with lysosomes. Fusion rates under standard conditions (control) were set as 100%. This translates to 3–12% of the bacteria or latex beads being positive for the lysosomal fluor. Means and standard deviations of ≥3 independent experiment are shown. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 compared to control. (A) Time course of phagosome–lysosome fusion. Fusion by 75 min (ECPs) or by 60 min (LBPs) was set as 100%. Fusion reactions contained ECPs (open circles, error bars downward) or LBPs (closed squares, error bars upward). (B and C) Compounds added at the beginning of the fusion reaction: 4 mM NEM, 10 mM BAPTA, 0.5 mg/mL RabGDI, 40 nM bafilomycin A1, 1 μM nigericin, 20 μM nocodazole. Reactions contained ECPs (B) or LBPs (C). (D–F) Reactions contained ECPs. (D) Colocalization of bacteria with lysosomal BSA rhodamine and percentage of bacteria with mean FRET intensity > 0 were calculated and expressed in percent of the respective control. One hundred percent (SD ± 73, n = 7) of colocalizing bacteria showed mean FRET intensity > 0. (E) Affinity purified anti-Rab7 or (F) GST-Rab7 WT or GST-Rab7T22N were added at the indicated final concentrations.

In vitro fusion of pure phagosomes containing inert latex beads (LBPs) with lysosomes (Fig. 3 and Fig. S2) proceeded with the same kinetics as ECP-lysosome fusion (Fig. 3A), was also dependent on physiological temperature and ATP, and was inhibited by NEM and RabGDI (Fig. 3C).

To directly test whether membrane fusion and not possibly membrane attachment was quantified, we performed a microscopic Foerster resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis, which yields a signal only after vesicle content mixing but not during vesicle attachment (24, 25). In samples containing an ATP-depleting system or an inhibitory soluble Q-SNARE mixture (see below), percentages of bacteria with mean FRET intensities > 0 and percentages of colocalization were reduced by the same degree (Fig. 3D), although membrane attachment should have occurred normally (26).

Phagosome–Lysosome Fusion Is Regulated by Rab7 and SNARE Proteins.

Rab7 was a prime candidate for a phagosome–lysosome fusion regulator (6). An affinity purified antibody against Rab7 (Fig. 3E) and GDP-locked, dominant-negative Rab7T22N-GST but not wild-type Rab7-GST (27, 28) (Fig. 3F) significantly inhibited ECP-lysosome fusion in vitro in a concentration-dependent manner.

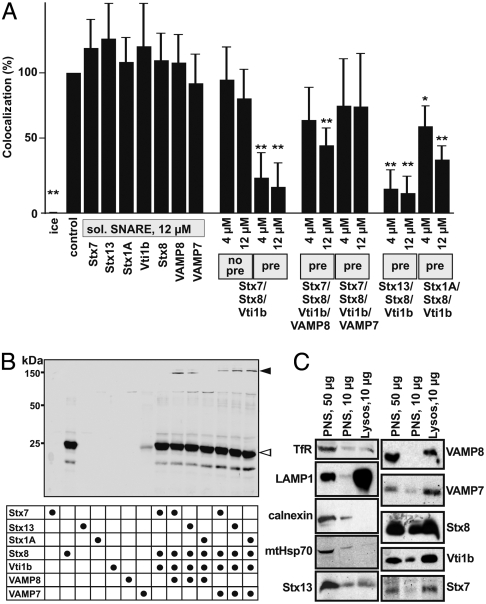

Few studies were published on the involvement of specific SNARE proteins in phagosome maturation (29), and none of them analyzed single maturation steps using in vitro fusion experiments. Late endocytic VAMP8, VAMP7, Vti1b, Stx7, and Stx8 but not early endocytic Stx13 were enriched in the lysosome fraction, and ER (calnexin) and mitochondrium (mtHsp70) proteins were virtually absent (Fig. 4C), arguing for high organelle purity and validating the SNARE enrichment data. To directly analyze SNARE participation in ECP-lysosome fusion, we used recombinant cytosolic domains of SNARE proteins (solSNAREs) (21, 26, 30). Lacking transmembrane domains, they are not able to support fusion reactions, yet can interact with membrane bound SNAREs. Single solSNAREs did not inhibit fusion (Fig. 4A). SolStx7, solStx8, and solVti1b, added together at the beginning of the fusion reaction, inhibited neither, but they did when preincubated together on ice (Fig. 4A). Preincubation of these solQ-SNAREs together with solVAMP8 or solVAMP7 as the suspected cognate R-SNAREs (31–33) prevented fusion inhibition (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

SNARE proteins in cell-free ECP-lysosome fusion. (A) Cell-free fusion of ECPs with lysosomes was carried out in the presence of single solSNAREs or combinations of solSNARES as indicated. Preincubations of solSNAREs for 90 min on ice were done (pre) where indicated or solSNAREs were added directly at the start of the fusion reaction (no pre). Data are means and standard deviations of ≥3 independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 compared to control. (B) Combinations of purified recombinant solSNAREs were mixed as indicated in equimolar ratios (12 μM each) and incubated for 90 min on ice. Samples were incubated with SDS-sample buffer without boiling and analyzed by Western blotting using an antibody to Stx8. The white arrowhead indicates the running position of solStx8; the black arrowhead indicates SDS resistant four-helix bundles. (C) PNS and purified lysosomes were analyzed for enrichment or depletion of various compartmental markers by Western blotting.

To analyze whether inhibition of phagosome–lysosome fusion in vitro by solSNARE combinations reflected SNARE specificity, we replaced the late endocytic Qa-SNARE Stx7 by an early endocytic (Stx13) or a neuronal Qa-SNARE (Stx1A). Preincubated solStx13/Stx8/Vti1b inhibited phagosome–lysosome fusion as efficiently as preincubated solStx7/Stx8/Vti1b, whereas preincubated solStx1A/Stx8/Vti1b inhibited fusion less, yet significantly (Fig. 4A). To analyze whether this inhibition pattern paralleled the capability of solSNAREs to form quarternary SNARE complexes during preincubation, we tested for SDS resistance of four-helix SNARE bundles (34) (SI Text). As expected from fusion results and from ref. 34, solStx7/Stx8/Vti1b/VAMP7 and solStx7/Stx8/Vti1b/VAMP8 produced SDS resistant complexes (Fig. 4B). These were absent when the protein mixtures had been heated in the sample buffer, which separates four-helix complexes. SolStx13/Stx8/Vti1b/VAMP8 and solStx13/Stx8/Vti1b/VAMP7 could also form SDS resistant complexes. Stx1A replaced Stx7 functionally only in combination with VAMP7 but not with VAMP8, in agreement with previous data (34).

In Vivo Maturation of SCPs.

As it was not clear whether SCPs fuse with lysosomes in macrophages, we quantified colocalization of phagosomes containing heat-killed (Phk) or viable (Plive) stationary-phase S. enterica with gold-rhodamine labeled lysosomes in J774E macrophages (SI Text and Fig. S6A). After 10 min of infection, ∼5% of Plive or Phk colocalized with the lysosomal dye, at 40 min ∼90% of Phk, but only ∼30% of Plive had fused with lysosomes. This difference remained unchanged during 145 min (Fig. S6A) and documents the maturation defect of Plive in J774E cells. Fluorescent labeling of Salmonella prior to infection did not alter colocalization of Plive and Phk with the lysosomal dye (Fig. S6B). At 55 min ∼75% of Plive and ∼55% of Phk were positive for Rab7-GFP; colocalization with Rab5-GFP was ∼20% for both types of phagosomes. Approximately 80% of Plive and ∼70% of Phk colocalized with LAMP1 at this time (Fig. S6C).

In Vitro Fusion of Early and Late SCPs with Endocytic Compartments of Different Maturation Stages.

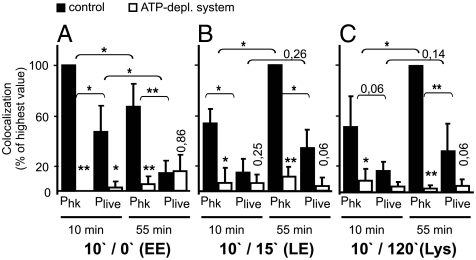

As phagosome maturation was affected by viable Salmonella, we tested whether fusion inhibition can be recapitulated in vitro. We extended the in vitro fusion assay to include the examination of fusogenicity of SCPs with earlier endocytic compartments. Different-aged Plive or Phk and different-aged endosomes or lysosomes were incubated either under standard conditions or in the presence of an ATP-depleting system. Fusion rates of different phagosomes with endocytic compartments of the same maturation stage were expressed as percent of the highest colocalization value (Fig. 5 and representative micrographs in Fig. S7). Fusion of early endosomes with early Plive or early Phk was significantly more pronounced than fusion of early endosomes with late phagosomes (Fig. 5A). Conversely, the fusion rate of early Phk with late endosomes or lysosomes was significantly lower than the fusion rate of late Phk with the same endocytic organelles (Fig. 5 B and C). In contrast, fusion competences of early or late Plive with late endosomes or lysosomes, respectively, were not significantly different (Fig. 5 B and C). For all endocytic compartments tested, the fusion rate with Phk was higher than with Plive.

Fig. 5.

In vitro fusion of Salmonella-containing phagosomes with different-aged endocytic compartments. In vitro fusion experiments were carried out with early (10 min) or late (55 min) phagosomes containing live (Plive) or heat-killed (Phk) S. enterica. Fusion rates of phagosomes with endosomes of different age cannot be directly compared, because fluor contents and volume of endocytic organelles likely change with maturation. Therefore, only fusion reactions with same-stage endocytic compartments were compared. Only phagosomes containing an intact membrane (bacteria were not antibody accessible) were considered. (A) Fusion reactions contained 10′/0′ endosomes (early endosomes, EE), (B) 10′/15′ endosomes (late endosomes, LE), or (C) 10′/120′ endosomes (lysosomes, Lys). Data are the means and standard deviations of ≥3 independent experiments. Asterisks or values above open bars without brackets mark p values comparing adjacent open and filled bars. ∗∗p < 0.01; *: p < 0, 05.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and used a cell-free assay to analyze fusion of different-aged endocytic compartments with bacteria-containing phagosomes. This microscopic assay for phagosome-endosome colocalization is conceptually similar to recently developed assays to study early endosome docking and fusion (21, 26, 35). Fusion yield in positive control samples containing different-aged endocytic compartments (2–20%) was well within the range of other systems reconstituting fusion of endosomes (21, 35, 36) or phagosomes (3, 37).

Authentic phagosome-lysosome fusion was observed in vitro, as reaction kinetics matched those of related cell-free fusion reactions (5, 21). Further, colocalization was strictly dependent on a physiological temperature and presence of ATP. Addition of cytosol increased fusion, but was not absolutely required as has been seen with other in vitro fusion reactions (21, 22), likely reflecting that fusion-enhancing peripheral membrane proteins such as NSF or Rab-GTPases are present on isolated membranes. Like late endosome–lysosome fusion (23), phagosome–lysosome fusion was reduced by calmodulin inhibitors, supporting previous reports on a role for calmodulin in phagosome–lysosome tethering (18). Fusion was also strongly inhibited by NEM and RabGDI, reflecting the requirements for NSF and Rab proteins (19, 20). An important Rab-GTPase in phagosome–lysosome fusion was Rab7. Purified Rab proteins were not geranylgeranylated and, hence, wild-type Rab7 did not promote fusion. Dominant-negative Rab7 inhibited phagosome–lysosome fusion, as its function is not fully dependent on the lipid modification (38, 39).

Reconstitution of not only ECP- but also LBP-lysosome fusion demonstrates the versatility of the presented assay. Isolated LBPs are almost pure allowing in vitro fusion experiments in a biochemically defined system, albeit with a nonphysiological phagosome load. The presented reconstitution system can help to molecularly investigate many of the observations made over the years with latex bead-fed phagocytes.

SolSNAREs have previously been used to test SNARE requirements in fusion of endocytic organelles in vitro or in semiintact cells (21, 26, 30). In our study, preincubated combinations of soluble Qa/b/c-SNAREs but not of Qa/b/c/R-SNAREs inhibited ECP-lysosome fusion. Because formation of SNARE four-helix bundles may proceed through Qa/b/c intermediates (40) and because our solSNAREs form SDS resistant quaternary complexes in vitro, we interpret this as follows: Ternary, three-helix solQa/b/c-SNARE complexes assemble during preincubation on ice at a low rate (34), similar to binary three-helix SNAP-25/Stx1 complexes (41). The preassembled Q-SNAREs engage organelle embedded cognate R-SNARE(s) in futile binding reactions and so efficiently block membrane fusion. Fusion inhibition is prevented, when solQa/b/c- and solR-SNAREs form a quaternary complex already during preincubation.

In vitro formation of SDS resistant complexes (as in refs. 34, 42, 43) and fusion inhibition by solQa/b/c-SNARE complexes were promiscuous in that they also occurred when late endocytic Stx7 (Qa) was replaced by early endosomal Stx13 (Qa) or neuronal Stx1A (Qa). There is precedence for SNARE promiscuity in the endocytic system, e.g., the functional replacement of Vti1b by other SNAREs in Vti1b knockout mice (44). In contrast, homotypic early endosome fusion in vitro was inhibited only by early endosomal (solStx13/Vti1a/Stx6) but not neuronal (solStx1/SNAP-25) SNARE domains (21). Yet, combinations of solStx7/Vti1b/Stx8 or solStx13/Vti1b/Stx8 inhibited phagosome–lysosome fusion more efficiently compared to solStx1A/Vti1b/Stx8. As the first two SNARE groups form SDS resistant four-helix bundles with either solVAMP7 or solVAMP8, which are both present on lysosomes, but the third one only with solVAMP7, this could indicate that both of these R-SNAREs are able to mediate phagosome–lysosome fusion. Inhibition by solStx1A/Vti1b/Stx8 is then less efficient, because only one of these R–SNAREs is inactivated by this complex.

Acidification of newly formed phagosomes supports phagolysosome formation (24) and is important for autophagosome–lysosome fusion (45). It may be important for vesicle budding in endosome and phagosome maturation (46, 47), yet, its role in fusion of late phagosomes or endosomes with lysosomes has not been analyzed directly. As neither bafilomycin nor nigericin inhibited phagosome–lysosome fusion, organelle acidification seems not to be required for this specific subreaction of phagolysosome formation.

To further understand diversion of phagosome maturation by intracellular pathogens, we compared fusion competence of early and late phagosomes containing live or heat-killed S. enterica with different-aged endocytic vesicles. We have shown that in vitro, early endosomes fuse more avidly with early than with late Phk and late endosomes and lysosomes are more fusogenic with late than with early Phk as expected. However, some fusion occurred between early Phk and late endocytic organelles and, conversely, late Phk and early endosomes. One explanation for this unexpected finding is heterogenity in the maturation stages of the phagosomes in that 10–20% of late Phk were still positive for early endocytic Rab5, yet negative for lysosomal gold rhodamine. Rab7 is present on the majority of endosomes that are only 0–10 min old, and this may explain fusion competence between early endosomes and late Phk in vitro. In vivo, this fusion may not readily occur due to spatial segregation from late phagosomes and phagolysosomes. Whether the presence of both Rabs on most early endosomes is a general macrophage characteristic remains to be investigated.

Fusion competence of both Plive and Phk with early endosomes decreased as phagosomes aged. But whereas Phk acquired fusion competence with late endocytic organelles, this was much less the case with Plive. It has been suggested (48) that late SCPs in macrophages retain Rab5 and Rab5 effectors, stay fusogenic with early endosomes, and that this sustained fusion occurs via an unconventional mechanism independent of ATP hydrolysis. We, too, observed ATP-independent fusion of late Plive with early endosomes, yet the fusion extent was much lower than fusion of early Plive with early endosomes. And in our study, Rab7-GFP but not Rab5-GFP was associated with the majority of late Plive. Hence, the strong fusion defect between late Plive and lysosomes was not caused by an early arrest as proposed in ref. 48 but rather by an arrest at a late maturation step.

Our data show that the low fusion competence of Plive with lysosomes in vivo was reconstituted in vitro and that reduced fusion competence of Plive was not restricted to lysosomes. Such generally reduced fusion competence of Plive is in line with the reported reduced accessibility of SCPs to incoming transferrin and dextran (10). Salmonella effector proteins such as spiC (49), which are secreted from the phagosome into the cytosol of infected cells via a type III secretion system, were discussed to be prime candidates for altering maturation of the SCP. However, phagosomes that contained Salmonella generally defective in effector protein secretion showed no enhanced fusion with lysosomes (11); hence, the role of effector proteins remains elusive. Against this background it was revealing that fusion of Plive with lysosomes in vitro was diminished with lysosomes from uninfected cells and did not require cytosol prepared from infected macrophages, which would be a prime source of secreted effectors. This suggests that the intraphagosomal bacteria had turned phagosomes fusion-incompetent before they were isolated. Whether reprogramming requires prior bacterial secretion or the presence of certain surface molecules, such as lipopolysaccharides, remains to be investigated. It has been proposed that diminished phagosome–lysosome fusion in vivo may be the result of an impaired capability of SCPs to attach to microtubules (MTs) and their reduced trafficking (50, 51). Disruption of MTs by nocodazole had only a minor effect on standard phagosome–lysosome fusion in our study, demonstrating that a possible need for MTs in phagosome maturation in vivo would be bypassed in vitro. Hence, inhibition of phagosome movement is not the (only) decisive factor in trafficking diversion of SCPs.

Material and Methods

Chemicals.

Antibodies, plasmids and recombinant proteins, buffers, and preparation of cytosol are described in SI Text. Cultivation of mammalian and bacterial cells and their use in infection experiments is described in SI Text.

Fluorescent Labeling of Endocytic Compartments.

To label lysosomes for in vitro fusion experiments with ECPs or LBPs, macrophages were incubated overnight (oN) in complete medium containing 50 μg/mL BSA rhodamine (5 μg/mL for FRET analysis). Cells were rinsed with PBS, incubated in complete medium containing ferrofluid (SI Text) for 5 min, rinsed twice with PBS, and chased at 37 °C for 2 h. For in vitro fusion experiments with SCPs, ferrofluid was incubated oN in BSA rhodamine in PBS and diluted in complete medium resulting in 100 μg/mL BSA rhodamine and 6 μL/mL ferrofluid. Macrophages were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C with BSA rhodamine/ferrofluid, rinsed twice with PBS, and chased as indicated. For biochemical analysis of purified endocytic compartments (SI Text), lysosomes were labeled with 50 μg/mL BSA rhodamine oN, chased for 2 h, and ferrofluid was added. To quantify phagosome–lysosome colocalization in vivo, macrophages were incubated in complete medium containing gold rhodamine for 1 h (infection with E. coli: OD520 = 1; infection with S. enterica: OD520 = 0, 4) or containing 50 μg/mL BSA rhodamine oN, rinsed thrice with PBS and chased for 3 h (infection with E. coli) or 2 h (infection with S. enterica or latex beads).

Preparation of Phagosomes and Endocytic Compartments.

Infection of macrophages is described in SI Text. Bacteria-containing phagosomes were prepared as in ref. 5 with modifications: Cells were sequentially washed with PBS/5 mM EDTA and homogenization buffer (HB), resuspended in HB/10 mg/mL BSA/1 × protease inhibitors, and homogenized in a Dounce homogenizer. A PNS was prepared at 450 × g for 3 min and centrifuged in a fixed angle rotor: When the rotor reached 12,000 × g, the centrifuge was turned off, the supernatant was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 6 min, and the pellet was resuspended in HB/10 mg/mL BSA. Preparation of LBPs is described in SI Text.

Using pulse/chase protocols, endocytic compartments were loaded with ferrofluid (EMG 508, Ferrotec Europe) and purified from a PNS as in ref. 17 with modifications (SI Text).

In Vitro Fusion Assay.

Standard fusion reactions contained 1.5 μL of 10 × salt solution (15 mM MgCl2, 1 M KCl), 1.5 μL of 10 × ATP regenerating system (SI Text), 0.15 μL 100 mM DTT, 2 mg/mL cytosol, 2 μL of the endosome or lysosome preparation and 2 μL of the phagosome preparation. Volumes were adjusted to 15 μL with HB. Each reaction contained lysosomes from 7.5 × 106 or late or early endosomes from 1.3 × 107 macrophages. Per reaction, bacteria-containing phagosomes from 7.5 × 105 macrophages or LBPs (final concentration: A600 = 0.3) were added. In control experiments, cytosol was replaced by HB. Recombinant proteins or pharmacologicals were either from a stock in HB or carrier-containing control samples were included. Fusion experiments were at 37 °C for 60 min and stopped by placing the tubes on ice. To identify bacteria not surrounded by an intact phagosome membrane, samples with SCPs were incubated with 5 μg/mL rabbit anti-Salmonella antibody at 4 °C for 30 min. This labeling was omitted in samples containing ECPs or LBPs. Samples were diluted with 1 mL cold HB. Poly-L-lysine coated coverslips were placed in a 24-well plate, 500 μL of the diluted fusion sample were added per well, and plates were centrifuged at 1,800 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Samples were fixed with 2.5% glutardialdehyde and 2% formaldehyde (FA) in HB (samples with ECPs or LBPs) or 3% FA in HB (samples with SCPs and samples for FRET analysis). After rinsing three times with PBS, samples were incubated in 1 mg/mL NaBH4 in PBS (ECPs or LBPs) or 50 mM NH4Cl in HB (SCPs and FRET analysis) for 30 min. Samples with SCPs were stained with a Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody. Coverslips were mounted in Mowiol. Samples were examined using a Zeiss Axioplan (ECPs or LBPs) or a Zeiss Axio Observer.Z1 microscope (SCPs and FRET analysis) equipped with 100×/1.4 oil immersion objectives and appropriate filter sets. Percentages of beads or green bacteria colocalizing with lysosomal BSA rhodamine were determined from 300 particles each in duplicates. In samples with SCPs, Cy5-labeled bacteria were excluded from analysis. All coverslips were anonymized. FRET analysis was performed according to the principle described by Youvan et al. (52) using Zeiss Axio Vision 4.7.1 software. ATTO488-labeled bacteria were defined as regions of interest (R) and mean FRET intensity was calculated for each R. Per sample, 200 bacteria were analyzed, and percentages of Rs with mean FRET intensities > 0 were expressed as percent of the positive control. FRET intensity for every pixel was displayed in a false color-coded image.

Statistical Analysis.

Means and standard deviations were calculated from independent experiments. Data were analyzed by the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test with significance assumed at p < 0.05 and high significance at p < 0.01.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank all colleagues who generously contributed plasmids and antibodies. This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 645) with initial support by the Volkswagen Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.J. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1007295107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Haas A. The phagosome: Compartment with a license to kill. Traffic. 2007;8:311–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desjardins M, Huber LA, Parton RG, Griffiths G. Biogenesis of phagolysosomes proceeds through a sequential series of interactions with the endocytic apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:677–688. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.5.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jahraus A, et al. In vitro fusion of phagosomes with different endocytic organelles from J774 macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30379–30390. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zerial M, McBride H. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:107–117. doi: 10.1038/35052055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alvarez-Dominguez C, et al. Phagocytosed live Listeria monocytogenes influences Rab5-regulated in vitro phagosome-endosome fusion. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13834–13843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison RE, et al. Phagosomes fuse with late endosomes and/or lysosomes by extension of membrane protrusions along microtubules: Role of Rab7 and RILP. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:6494–6506. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.18.6494-6506.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith AC, et al. A network of Rab GTPases controls phagosome maturation and is modulated by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:263–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs: Engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drecktrah D, Knodler LA, Ireland R, Steele-Mortimer O. The mechanism of Salmonella entry determines the vacuolar environment and intracellular gene expression. Traffic. 2006;7:39–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathman M, Barker LP, Falkow S. The unique trafficking pattern of Salmonella typhimurium-containing phagosomes in murine macrophages is independent of the mechanism of bacterial entry. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1475–1485. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1475-1485.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garvis SG, Beuzon CR, Holden DW. A role for the PhoP/Q regulon in inhibition of fusion between lysosomes and Salmonella-containing vacuoles in macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:731–744. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchmeier NA, Heffron F. Inhibition of macrophage phagosome-lysosome fusion by Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2232–2238. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2232-2238.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oh YK, et al. Rapid and complete fusion of macrophage lysosomes with phagosomes containing Salmonella typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3877–3883. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3877-3883.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukherjee K, et al. Live Salmonella recruits N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein on phagosomal membrane and promotes fusion with early endosome. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:741–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vergne I, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest: Mycobacterial phosphatidylinositol analog phosphatidylinositol mannoside stimulates early endosomal fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:751–760. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mukherjee K, et al. Diverting intracellular trafficking of Salmonella to the lysosome through activation of the late endocytic Rab7 by intracellular delivery of muramyl dipeptide. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3693–3701. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li HS, Stolz DB, Romero G. Characterization of endocytic vesicles using magnetic microbeads coated with signalling ligands. Traffic. 2005;6:324–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stockinger W, et al. Differential requirements for actin polymerization, calmodulin, and Ca2+ define distinct stages of lysosome/phagosome targeting. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:1697–1710. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullrich O, et al. Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor as a general regulator for the membrane association of Rab proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18143–18150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra V, et al. Role of an N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive transport component in promoting fusion of transport vesicles with cisternae of the Golgi stack. Cell. 1988;54:221–227. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90554-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandhorst D, et al. Homotypic fusion of early endosomes: SNAREs do not determine fusion specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2701–2706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haas A, Conradt B, Wickner W. G-protein ligands inhibit in vitro reactions of vacuole inheritance. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:87–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pryor PR, et al. The role of intraorganellar Ca2+ in late endosome-lysosome heterotypic fusion and in the reformation of lysosomes from hybrid organelles. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:1053–1062. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.5.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yates RM, Hermetter A, Russell DG. The kinetics of phagosome maturation as a function of phagosome/lysosome fusion and acquisition of hydrolytic activity. Traffic. 2005;6:413–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu P, Brand L. Resonance energy transfer: Methods and applications. Anal Biochem. 1994;218:1–13. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geumann U, et al. SNARE function is not involved in early endosome docking. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5327–5337. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-05-0457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantalupo G, et al. Rab-interacting lysosomal protein (RILP): The Rab7 effector required for transport to lysosomes. EMBO J. 2001;20:683–693. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bucci C, et al. Rab7: A key to lysosome biogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:467–480. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins RF, Schreiber AD, Grinstein S, Trimble WS. Syntaxins 13 and 7 function at distinct steps during phagocytosis. J Immunol. 2002;169:3250–3256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hua Y, Scheller RH. Three SNARE complexes cooperate to mediate membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8065–8070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131214798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullock BM, et al. Syntaxin 7 is localized to late endosome compartments, associates with VAMP 8, and is required for late endosome-lysosome fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3137–3153. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.9.3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pryor PR, et al. Combinatorial SNARE complexes with VAMP7 or VAMP8 define different late endocytic fusion events. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:590–595. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antonin W, et al. The R-SNARE endobrevin/VAMP-8 mediates homotypic fusion of early endosomes and late endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3289–3298. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antonin W, et al. A SNARE complex mediating fusion of late endosomes defines conserved properties of SNARE structure and function. EMBO J. 2000;19:6453–6464. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rizzoli SO, et al. Evidence for early endosome-like fusion of recently endocytosed synaptic vesicles. Traffic. 2006;7:1163–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robinson LJ, Aniento F, Gruenberg J. NSF is required for transport from early to late endosomes. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 17):2079–2087. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.17.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayorga LS, Bertini F, Stahl PD. Fusion of newly formed phagosomes with endosomes in intact cells and in a cell-free system. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6511–6517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li G, Barbieri MA, Colombo MI, Stahl PD. Structural features of the GTP-binding defective Rab5 mutants required for their inhibitory activity on endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:14631–14635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stenmark H, et al. Inhibition of Rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J. 1994;13:1287–1296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiebig KM, Rice LM, Pollock E, Brunger AT. Folding intermediates of SNARE complex assembly. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:117–123. doi: 10.1038/5803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fasshauer D, et al. Structural changes are associated with soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor complex formation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28036–28041. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.28036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fasshauer D, et al. Mixed and non-cognate SNARE complexes. Characterization of assembly and biophysical properties. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15440–15446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang B, et al. SNARE interactions are not selective. Implications for membrane fusion specificity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5649–5653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atlashkin V, et al. Deletion of the SNARE vti1b in mice results in the loss of a single SNARE partner, Syntaxin 8. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5198–5207. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.15.5198-5207.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawai A, et al. Autophagosome-lysosome fusion depends on the pH in acidic compartments in CHO cells. Autophagy. 2007;3:154–157. doi: 10.4161/auto.3634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gu F, Gruenberg J. ARF1 regulates pH-dependent COP functions in the early endocytic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8154–8160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beron W, Mayorga LS, Colombo MI, Stahl PD. Recruitment of coat-protein-complex proteins on to phagosomal membranes is regulated by a brefeldin A-sensitive ADP-ribosylation factor. Biochem J . 2001;355:409–415. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3550409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parashuraman S, Madan R, Mukhopadhyay A. NSF independent fusion of Salmonella-containing late phagosomes with early endosomes. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1251–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uchiya K, et al. A Salmonella virulence protein that inhibits cellular trafficking. EMBO J. 1999;18:3924–3933. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.14.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shotland Y, Kramer H, Groisman EA. The Salmonella SpiC protein targets the mammalian Hook3 protein function to alter cellular trafficking. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49:1565–1576. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marsman M, et al. Dynein-mediated vesicle transport controls intracellular Salmonella replication. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2954–2964. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Youvan D, et al. Calibration of fluorescence resonance energy transfer in microscopy using genetically engineered GFP derivates on nickel chelating beads. Biotechnology. 1997;3:1–18. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.