Abstract

We present a patient (male 54 years) with a history of renal transplant who 14 years post transplantation developed a symptomatic (stridor) laryngeal Epstein Barr virus (EBV)—associated smooth muscle tumor (EBV-SMT) in the absence of concomitant disease elsewhere. Nine years post transplantation the patient developed a subcutaneous EBV-SMT tumor located on the calf. The laryngeal tumor displayed low-grade nuclear atypia and was infiltrating into the surrounding soft tissue, focally ulcerating through the overlying epithelium. Histologic features included: neoplastic cells with myoid differentiation, a component of primitive appearing small mesenchymal cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, mitotic activity, intralesional small to medium sized blood vessels and T-lymphocytes. Both the myoid and small cell mesenchymal components strongly expressed smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon, but not desmin, cytokeratins, CD34 or S-100 protein. There was strong positive nuclear reaction for EBV-RNA on in situ hybridization (EBER). No other tumor was detected on clinical and radiological examinations and no evidence of tumor in other sites, over 8 months of follow-up, till death was detected. This case emphasizes the importance of considering this pathologic entity when solitary smooth muscle actin-expressing tumors are encountered in the larynx of immunocompromised patients.

Keywords: Larynx, Epstein Barr Virus associated smooth muscle tumour, Leiomyosarcoma, EBV

Introduction

Primary mesenchymal tumors of the larynx with smooth muscle differentiation (leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas) are relatively rare [1–4]. The existence of an even less common form of laryngeal smooth muscle tumor is associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection in the setting of immune-compromised patients. To the best of our knowledge only three primary laryngeal EBV-associated smooth muscle tumors (EBV-SMT) have been reported in the English literature [5, 6]. All of these occurred in the context of concomitant multi-focal disease in other parts of the body. We herein provide the clinicopathological features of yet another case of a laryngeal EBV-SMT.

Case Report

The patient is a Chinese man who developed chronic renal failure and had a renal transplant at 40 years of age. The patient was placed on an immunosuppressive drug regime comprising cyclosporine A and azathioprine. Fourteen years post-transplantation (at age 54), he developed progressively worsening stridor. A non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck region revealed an ovoid opacity measuring 1.5 × 1.2 cm in the larynx just below the vocal cords with partial obstruction of the lumen (Fig. 1a). Pre-operative chest X-rays, ultra-sound examination of kidneys and hepatobiliary system as well as magnetic resonance imagine (MRI) of the brain did not show any concurrent tumors. Biopsy of the lesion was performed and based on the presence of high cellularity, mild nuclear atypia, the presence of mitotic figures and positive immunoreactivity for SMA, h-caldesmon, this was reported as a leiomyosarcoma. A total laryngectomy was performed. With no evidence of local recurrence metastasis or other tumor manifestation, the patient passed away 8 months after the laryngectomy from septicemia.

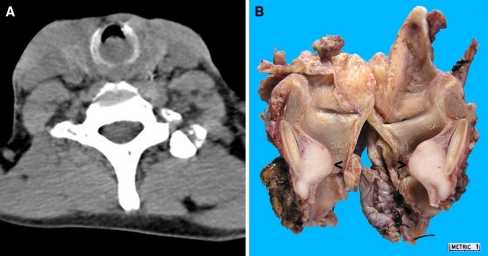

Fig. 1.

A laryngeal tumor located below the false vocal cords. a Non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the neck was performed and revealed a 1.5 cm by 1.2 cm ovoid opacity in the larynx located below the vocal cords. b The laryngectomy specimen was cut open posteriorly and the laryngeal nodule (arrowed) arising in close apposition to the posterior luminal surface of the cricoid cartilage was bisected to reveal a tan colored surface

When working up this case, we found that the patient had a 7 mm large subcutaneous lesion on the calf excised 5 year prior to the presentation of the laryngeal tumor. On review (including in situ hybridization for EBV), the calf tumor proved to be an EBV-SMT with histological features resembling an angioleiomyoma.

Materials and Methods

The tissue was fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Four-micron thick sections were cut and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). An immunohistochemical study was performed with the following commercial antibodies from DAKO: smooth muscle actin (SMA [1:1000]), desmin (1:100), CD34 (1:200), S-100 protein (1:2000), pan-cytokeratin (AE1/AE3 epitope, 1:300), chromogranin A (1:800), synaptophysin (1:50), CD3 (1:100) and CD45 (1:750).

Epstein-Barr virus early RNA (EBER) was detected using an EBER peptide nucleic acid probe and in situ hybridization detection kit (DAKO).

Results

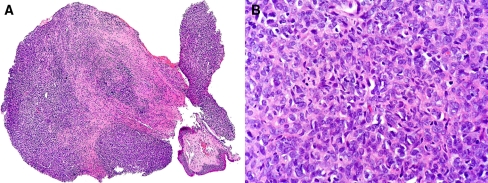

The biopsy showed a hypercellular mesenchymal neoplasm composed of small cells with oval to elongated hyperchromatic nuclei with scanty cytoplasm. The neoplasm displayed occasional mitotic figures, nuclear atypia and cellular crowding (Fig. 2). Neoplastic cells displayed strong and diffuse immunoreactivity for SMA and h-caldesmon, and were negative for desmin, S100-protein, cytokeratins (AE1/AE3) and CD34 (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

The biopsy of the laryngeal tumor. H&E stained section showing a Low power magnification of a mesenchymal neoplasm under the partially detached laryngeal mucosa. b High power magnification revealed hypercellularity with nuclear crowding and low-grade nuclear atypia

The laryngectomy specimen revealed a tan-colored ovoid, fairly well circumscribed, non-encapsulated, 2.0 cm large mass located on the posterior luminal surface of the cricoid cartilage below the true vocal cords (Fig. 1b).

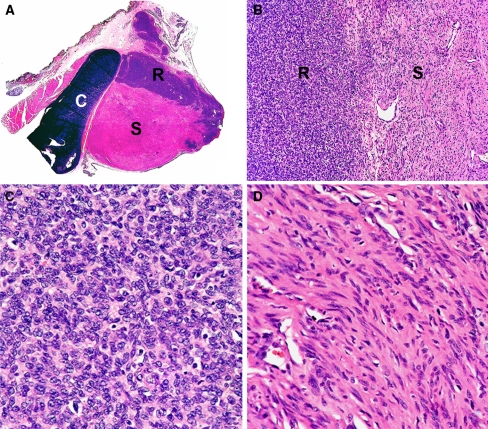

On routine histological examination, the tumor was seen to infiltrate into the surrounding soft tissue along broad fronts and to focally ulcerate through the overlying epithelium. The different neoplastic tissue components were sharply demarcated and was composed, on the one hand, of primitive-looking small mesenchymal cells with hyperchromatic, round nuclei and small amounts of amphophilic cytoplasm, and on the other hand, of neoplastic cells with oval nuclei and moderately abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with myoid characteristics (Fig. 3). The nuclei were mildly pleomorphic and had finely condensed chromatin and small, but distinct nucleoli. Mitotic figures were more commonly seen in the round cell areas (1–3 per 10 high power field [hpf]) than in the spindle cell areas (1 per 40 hpf). In both components of neoplastic tissue, scattered small lymphocytes were present.

Fig. 3.

The tumor has two distinct components. a A section of the tumor with attached cartilage (labeled C), skeletal and loose connective tissue was stained with H&E, showing two distinct areas (labeled R and S) within the tumor. b The round cell area, labeled R, was clearly demarcated from the spindle cell area, labeled S (magnification ×100). c The round cell area was composed of primitive-looking cells with hyperchromatic, round nuclei and amphophilic cytoplasm (magnification ×400). d The spindle cell area was composed of cells with thin elongated nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm (magnification ×400). High vascular density was a characteristic of this area

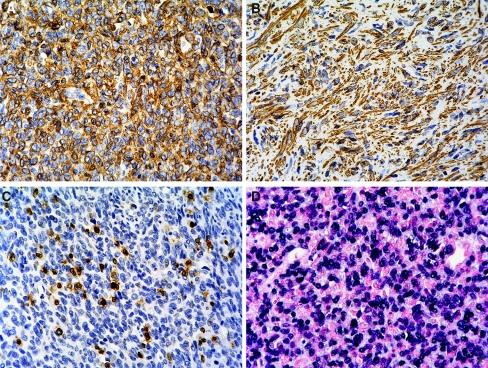

In the immunohistochemical study, neoplastic cells in both round cell and spindle cell areas uniformly and strongly expressed SMA (Fig. 4a, b). There was no expression of desmin, S-100 protein, CD34, cytokeratins, chromogranin A or synaptophysin, CD45 (lymphocyte common antigen) highlighted scattered lymphocytes within the tumor and they were found to be predominantly of T-cell lineage (CD3 positive, Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Smooth muscle actin (SMA) expression and EBV RNA is detected in the tumour cells. Sections of the tumor were stained with SMA and CD3 antibodies and couterstained with hematoxylin. Both the round cell (a) and spindle cell (b) areas express SMA. c CD3 antibodies stained scattered T-lymphocytes within the tumor (magnification, all ×400). d In situ hybridization was used to detect the presence of EBER. EBER was diffusely present in the nuclei of the tumor cells (magnification ×400)

In situ hybridization revealed the presence of EBER within most of the tumor cells of both the round cell and spindle cell areas. EBER was not detected in the intralesional lymphocytes or adjacent non-neoplastic tissues (Fig. 4d).

Discussion

Epstein-Barr virus is a common human pathogen and has been shown to play an important role in the pathogenesis of a number of different lymphomas [7] and undifferentiated carcinoma most frequently, but not exclusively occurring in the nasopharynx [8, 9]. EBV-associated mesenchymal tumors with smooth muscle differentiation are only more recently recognized [10, 11]. EBV-SMTs appear to exclusively occur in immunocompromised patients, most frequently in the setting of HIV infection or in patients on immunosuppressive treatment for organ transplantation. EBV-SMTs invariably express SMA. However, reportedly the expression of another muscle marker, desmin (as in this case) is not consistent [6]. Although the role of EBV in the pathogenesis of this tumor is not proven, the presence of clonal EBV DNA in tissue from the same tumor suggests that each tumor is derived from a single EBV infection [10, 11]. Moreover, it has been shown that multiple infectious events can account for the development of multifocal tumors [6]. Furthermore, the occurrence of EBV-SMT in sites that are unusual for leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas, indicate that EBV plays at least a permissive role in tumorigenesis. EBV-SMT commonly occurs as multifocal/multicentric disease with no metastatic events documented and surgery is the preferred therapeutic option. Interestingly, modulation of antiviral treatment has been shown to correlate with tumor burden in one patient [12].

Prior to this report, only three EBV-SMT of the larynx have been described [5, 6]. All these were associated with concomitant multi-focal disease. All patients were found to have lung tumor nodules and two had disease involving the liver. Our patient presented with a laryngeal tumor with no evidence of tumor in other sites over 8 months of follow-up till death. However, the previously diagnosed cutaneous angioleiomyoma (5 years prior to the presentation of the laryngeal tumor) that we found while working up the case displayed strong nuclear positivity in an EBER-ISH study. This tumor was thus an EBV-SMT with histological features virtually identical to a sporadic cutaneous angioleiomyoma. This is further strengthened by the fact that sporadic cutaneous smooth muscle tumors including angioleiomyomas have shown no association with EBV [13].

From a differential diagnostic perspective, a primary leiomyoma, primary or metastatic leiomyosarcoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (IMT) of the larynx should be considered. All these tumors are composed of spindle cells expressing SMA [14, 15]. Even in the setting of multifocal/multicentric disease, death due to tumor manifestations is exceptionally rare in contrast to leiomyosarcomas which pursue a more aggressive clinical course. Roughly half of EBV-SMT display histological features (round cell areas, a prominent vascular component and significant number of intratumoral lymphocytes) which would allow for a tentative diagnosis to be made and confirmed with an EBER-ISH study. For the EBV-SMTs that do not display these histomorphological features, differential diagnostic difficulties arise. Especially so since somatic soft tissue leiomyosarcomas may display only a mild degree of nuclear atypia and low mitotic activity (as low as <1 mitotic figure/10HPF). In these instances, awareness of the clinical setting is of paramount importance in order to contemplate the correct diagnosis. Moreover, even in EBV-SMTs with a small cell component, differentiation from epithelioid leiomyosarcoma may be difficult on small biopsies (as in this case). IMTs are composed of spindle cells in a variably edematous, myxoid and collagenous stroma, and contain inflammatory infiltrate composed primarily of plasma cells and lymphocytes with occasional eosinophils and neutrophils [16]. ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) expression is detected in about 50% of IMTs [17] and may aid in establishing the correct diagnosis.

In summary, we present an EBV-associated smooth muscle tumor that occurred in the larynx in the absence of concomitant disease elsewhere and with no other tumor manifestations during a follow up of 8 months. This case emphasizes the importance of considering this pathologic entity when solitary smooth muscle actin-expressing tumors are encountered in the larynx of immunocompromised patients.

References

- 1.McKiernan DC, Watters GW. Smooth muscle tumours of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:77–79. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100129317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goda JS, Saravanan K, Vashistha RK, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx: case report and review of the literature. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87:283–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rimmer J, Giddings CE, Mady S. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120:e3. doi: 10.1017/S0022215105008315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu Y, Zhou S, Wang S. Vascular leiomyoma of the larynx: a rare entity. Three case reports and literature review. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2008;70:264–267. doi: 10.1159/000133652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gan EC, Lau DP, Chuah KL. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumour mimicking bilateral vocal process granuloma. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:100–104. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107007682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deyrup AT, Lee VK, Hill CE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors are distinctive mesenchymal tumors reflecting multiple infection events: a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 29 tumors from 19 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:75–82. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000178088.69394.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rezk SA, Weiss LM. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1293–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein G, Giovanella BC, Lindahl T, et al. Direct evidence for the presence of Epstein-Barr virus DNA and nuclear antigen in malignant epithelial cells from patients with poorly differentiated carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4737–4741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.12.4737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pathmanathan R, Prasad U, Sadler R, et al. Clonal proliferations of cells infected with Epstein-Barr virus in preinvasive lesions related to nasopharyngeal carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:693–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199509143331103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee ES, Locker J, Nalesnik M, et al. The association of Epstein-Barr virus with smooth-muscle tumors occurring after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:19–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501053320104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClain KL, Leach CT, Jenson HB, et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in children with AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:12–18. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501053320103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogatsch H, Bonatti H, Menet A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated multicentric leiomyosarcoma in an adult patient after heart transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:614–621. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200004000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez MP, Krejci-Manwaring J, Davis TL. Epstein-Barr virus is not associated with angioleiomyomas, or other cutaneous smooth muscle tumors in immunocompetent individuals. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:507–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volker HU, Scheich M, Zettl A, et al. Laryngeal inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors: different clinical appearance and histomorphologic presentation of one entity. Head Neck. 2009. doi:10.1002/hed.21232. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marioni G, Staffieri C, Marino F, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the larynx: critical analysis of the diagnostic role played by immunohistochemistry. Am J Otolaryngol. 2005;26:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffin CM, Watterson J, Priest JR, et al. Extrapulmonary inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor (inflammatory pseudotumor). A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 84 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:859–872. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199508000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin CA, Hawkins AL, Dvorak C, et al. Recurrent involvement of 2p23 in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2776–2780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]