Abstract

Patients affected by autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, dermatomyositis) who are treated with methotrexate (MTX) sometimes develop lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs). In approximately 40% of reported cases, the affected sites have been extranodal, and have included the gastrointestinal tract, skin, lung, kidney, and soft tissues. However, MTX-associated LPD (MTX-LPD) is extremely rare in the oral cavity. Here we report a 69-year-old Japanese woman with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) who developed MTX-LPD resembling Hodgkin’s disease—so-called “Hodgkin-like lesion”—in the left upper jaw. Histopathologically, large atypical lymphoid cells including Hodgkin or Reed-Sternberg-like cells were found to have infiltrated into granulation tissue in the ulcerative oral mucosa. Immunohistochemistry showed that the large atypical cells were positive for CD20, CD30 and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-latent infection membrane protein-1 (LMP-1) and negative for CD15. EBV was detected by in situ hybridization (ISH) with EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for LMP-1 and EBNA-2 in material taken from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimen. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of MTX-related EBV-associated LPD (MTX-EBVLPD), “Hodgkin-like lesion”, of the oral cavity in a patient with RA.

Keywords: Methotrexate-related Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorder (MTX-EBVLPD), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), Hodgkin-like lesion, Oral cavity

Introduction

Patients with immunodeficiency have a higher risk of lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) than immunocompetent individuals. Many immunodeficiency-associated LPDs have a tendency to develop at extranodal sites, exhibiting a diffuse aggressive histology, a B-cell origin associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and rapid clinical progression [1]. Methotrexate (MTX) is regarded as an effective immunosuppressive agent for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and is therapeutically effective in many cases that are resistant to some anti-rheumatic drugs [2]. Recently, it has been shown that patients with RA and other rheumatic diseases treated with MTX have an increased risk of developing LPDs or lymphomas [3]. Interestingly, Mariette et al. [4] have indicated that, whereas the risk of non-Hodgkin disease (non-Hodgkin lymphoma: NHL) was not significantly increased in RA patients treated with MTX, their incidence of Hodgkin disease (classical Hodgkin lymphoma: CHL) appeared to be higher. Moreover, approximately 50% of LPDs are EBV-positive [3]. Overall, approximately 40% of reported cases have involved extranodal sites, including the gastrointestinal tract, skin, lung, kidney, and soft tissues [3, 5]. However, to our knowledge, the English literature includes only five case reports as a MTX-associated LPD (MTX-LPD) in the oral cavity [6–9]. Observation studies germane to the relationship between LPD and immunosuppression in the oral cavity are listed in Table 1. Thus currently, little is known about the clinicopathological features of extranodal EBV-positive MTX-LPD resembling CHL, so-called “Hodgkin-like lesion”, at oral sites in RA patients.

Table 1.

Summary of the clinicopathological findings in oral cavity LPD and immunosuppression

| Source of IS | Site | Age [average] | Sex (M/F) | PT | EBV | Histology | Treatment | Author [ref.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTX (5) | Gingiva (3) | 44–70 [61] | (0/3) | ulcer | + | DLBCL | WD MTX | Tanaka et al. [7] |

| ulcer | + | DLBCL | WD MTX | Uneda et al. [9] | ||||

| ulcer | + | Hodgkin–like | WD MTX, Sur | Current case | ||||

| Tongue (1) | 80 [80] | (1/0) | ulcer | + | B-cell type | NA | Dojcinov et al. [8] | |

| Oral cavity (1) | 73 [73] | (0/1) | ? | + | PSLLPI | WD MTX | Kojima et al. [6] | |

| CYA (1) | Tongue (1) | 48 [48] | (0/1) | ulcer | + | B-cell type | WD CYA | Dojcinov et al. [8] |

| AZA (1) | Gingiva (1) | 42 [42] | (1/0) | ulcer | + | B-cell type | NA | Dojcinov et al. [8] |

| Advanced | Tongue (6) | 64–89 [76] | (2/4) | ulcer | + | B-cell type | NE(4)/NA(1)/Rad(1) | Dojcinov et al. [8] |

| Age (7) | Palate (1) | 80 [80] | (0/1) | ulcer | + | B-cell type | Rad | Dojcinov et al. [8] |

IS immunosuppression, MTX methotrexate, CYA cyclosporine-A, AZA azathioprine, M mail, F female, PT presentation, EBV Epstein-Barr virus, DLBCL diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, PSLLPI polymorphous small lymphocytic lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, WD withdrawal, Rad Radiotherapy, Sur Surgical resection, NA not available, NE not examined

?, unknown; (), (total number)

Here we report a rare case of MTX-related EBV-associated LPD (MTX-EBVLPD), “Hodgkin-like lesion”, in the oral cavity of a patient with RA.

Case Report

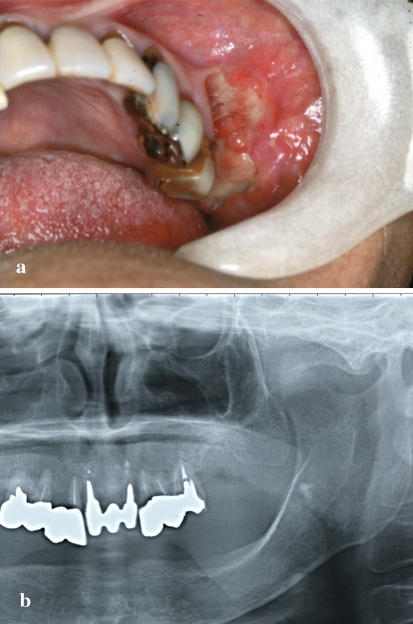

A 69-year-old Japanese woman was referred to Meikai University Hospital because of a 1-month history of pain in the left upper molar region to cold water after tooth loss because of severe periodontitis. The patient had rheumatoid arthritis (RA) for 7–8 years, and had been receiving MTX (6 mg/week) for the last several years. Laboratory data including blood parameters were within the normal ranges. She was not being treated with any other drugs, and had no illness attributable to the immunosuppressive effect of MTX. Extra-oral examination revealed no remarkable features, and no regional or generalized lymph node swelling was apparent. Intra-oral examination showed swelling of the gingivobuccal mucosa of the left upper jaw with ulcer formation in the premolar to molar region (Fig. 1a). Radiographic examination revealed no evidence of osteolysis (Fig. 1b). The clinical diagnosis was a gingival tumor versus infection. The pathological diagnosis of a biopsy specimen was ulcer with granulomatous inflammation, suspicious for specific infection. However, special stains including Ziehl-Neelsen, periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Grocott for acid-fast bacilli and fungi revealed no detectable microorganisms. Accordingly, the patient underwent a re-biopsy, and this time the pathological diagnosis was MTX-associated lymphoma. The patient was therefore instructed to stop discontinue MTX. The lesion was excised and the patient recovered and with a good clinical course.

Fig. 1.

Intra-oral findings, and radiologic and gross features of the tumor. a Intraoral view showing swollen ulcerative mucosa in the upper jaw buccal gingiva from the first premolar to molar. b Panoramic radiograph showing absence of neoplastic osteolysis in the area surrounding the lesion

The case study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Meikai University School of Dentistry (A0832).

Histologic Assessment

Each of the specimens obtained (biopsy, re-biopsy, and surgical specimens) were fixed in 10% formalin solution, processed routinely, and embedded in paraffin. For light microscopic examination, 4-μm-thick sections were prepared and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE). In addition, special stains (Ziehl-Neelsen, PAS and Grocott) for acid-fast bacilli and fungi were employed.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections of each of the samples (biopsy, re-biopsy, and surgical) were mounted on glass microscope slides. They were then deparaffinized and immersed in absolute methanol containing 0.3% H2O2 for 15 min at room temperature to block endogenous peroxidase activity. After washing, the sections were immersed in 0.01 M citrate buffer, pH 6.0, and heated in a microwave oven for 5 min at high voltage and then for 15 min at low voltage. They were then treated with appropriately diluted mouse monoclonal antibodies against human CD3, CD15, CD20, CD30 and CD56 (Nichirei Co., Tokyo, Japan), CD45, CD45RO, CD68, EBV-latent infection membrane protein-1 (EBV-LMP-1), Ki-67 and HMB-45 (Dako, A/S, Denmark), and an appropriately diluted rabbit polyclonal antibody against human S-100 (Dako). Each antibody was applied to the sections for 1 h at room temperature, followed by a pre-diluted anti-mouse or rabbit IgG antibody conjugated with peroxidase (Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min at room temperature. The sections were immersed for 8 min in 0.05% 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) in 0.05 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.5) containing 0.01% H2O2, and then counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin.

Imunoreactivity for CD15, CD20, CD30, CD45, CD45RO and EBV-LMP-1 was examined for differentiation between Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma: NLPHL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). Furthermore, immunoreactivity for CD15, CD20, CD30 and LMP-1 was examined for differentiation between CHL (CD15(+), CD20(±), CD30(+), CD45(−), LMP-1(±)) and NLPHL (CD15(−), CD20(+), CD30(−), CD45(+), LMP-1(−)). Immunoreactivity indicative of Hodgkin-like lesion (CD15(−), CD20(+), CD30(+), LMP-1(+)) was also examined. Attention was also paid to the important markers of Hodgkin-like lesion, CD15, CD20 and CD30, and the presence of Reed-Sternberg-like cells in localized mucosal ulcerative EBV-positive LPDs [8, 10].

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization (ISH) with EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) oligonucleotides was performed to test for the presence of EBV small RNA in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections using the hybridization kit (Dako) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

To test for the presence of EBV genes (LMP-1 and EBNA-2) in each specimen (biopsy, re-biopsy and surgical), formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded materials were subjected to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis using a TaKaRa DEXPATTM kit (TaKaRa, Japan) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. They are LMP-1 [11] and EBNA-2 [12] primer design and amplification programs are listed in Table 2. The Raji (EBV-positive Burkitt’s lymphoma) cell line was used as a positive control, having been subcultured from material obtained from the Japan Health Sciences Foundation Health Science Research Resources Bank (HSRRB).

Table 2.

Primers design of EBV, sequences and amplification programs for polymerase chain reaction

| Target | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | size(bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | (F) GCACCGTCAAGGCTGAGAAC | 94°C | 94°C | 58°C | 72°C | 72°C | 4°C | ||

| (R) TGGTGAAGACGCCAGTGGA | 5 min | 30 s | 30 s | 1 min | 7 min | 45 cycle | 138 | ||

| LMP-1 | (F) CCAGACAGCAGCCAATTGTC | 94°C | 94°C | 58°C | 72°C | 72°C | 4°C | ||

| (R) GGTAGAAGACCCCCTCTTAC | 5 min | 30 s | 30 s | 1 min | 7 min | 45 cycle | 129 | ||

| EBNA-2 | (F) AGGCTGCCCACCCTGAGGAT | 94°C | 94°C | 58°C | 72°C | 72°C | 4°C | ||

| (R) GCCACCTGGCAGCCCTAAAG | 5 min | 30 s | 30 s | 1 min | 7 min | 45 cycle | 186 |

Results

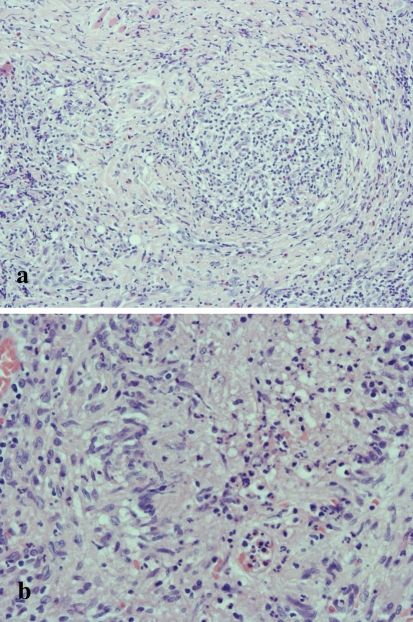

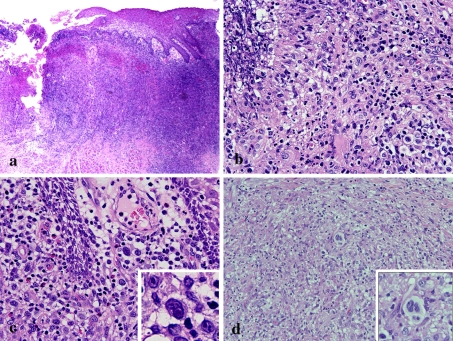

The first biopsy specimen demonstrated granuloma formation (Fig. 2a) and a palisade-like arrangement of epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocyte-based severe inflammatory cell infiltration with eosinophils, and caseous-like necrosis (Fig. 2b). In addition, special stains (Ziehl-Neelsen stain, PAS and Grocott) for acid-fast bacilli and fungi detected no microorganisms (data not shown). Re-biopsy of the ulcer (Fig. 3a) revealed numerous large, round atypical cells surrounding an area of ulcerative necrosis (Fig. 3b). Atypical cells with large single nuclei were noted in the edematous submucosal stroma (Fig. 3c) and a few Reed-Sternberg-like cells were found in the granulomatous areas (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 2.

Microscopic features of the biopsy specimen. a Granulomatous tissue is evident in the submucosal stroma with lymphocyte-based area of severe inflammation (HE, original magnification × 100). b Palisade-like arrangement of epithelioid cells with caseous-like necrosis found in the granulomatous lesion (HE, original magnification × 200)

Fig. 3.

Microscopic features of the re-biopsy specimen. a Ulcer and severe inflammatory cell infiltration is evident in the submucosa (HE, original magnification × 20). b Inflammation of atypical large round cells is evident around the ulcer (HE, original magnification × 200). c Atypical round large cells are evident in the edematous submucosal stroma (inset; atypical cells with large nuclei), (HE, original magnification × 200). d Atypical large cells (inset; Reed-Sternberg like cells) are evident the epithelioid granulomatous tissue with a background of morphologically unremarkable inflammatory cells (HE, original magnification × 100)

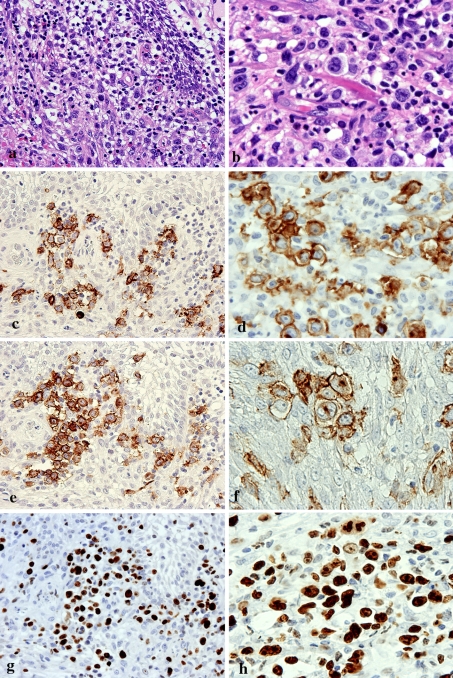

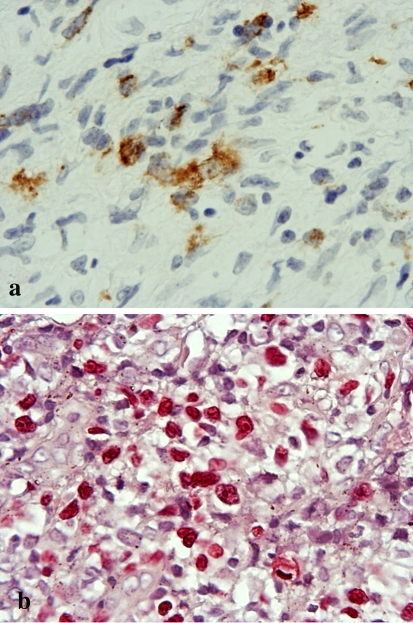

Immunohistochemistry of the edematous submucosal stroma (Fig. 4a) and granulomatous area (Fig. 4b) showed that the atypical large cells were positive for CD20, CD30 and Ki-67 (Fig. 4c–h) and also for EBV-latent infection membrane protein-1 (EBV-LMP-1) (Fig. 5a). In situ hybridization (ISH) also revealed the presence of EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) (Fig. 5b). There was no immunoreactivity for CD3, CD15, CD45, CD45RO, CD56, CD68, S-100 protein or HMB-45. The patient was diagnosed as having MTX-LPD, and received instructions to discontinue taking MTX. She then underwent surgical resection of the ulcerous lesion.

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical features of the re-biopsy specimen. a, c, e, g, showing an edematous submcosal stroma (original magnification × 400). b, d, f, h Granuloma formation (original magnification × 400). a HE staining of the edematous submcosal stroma. b HE staining of the granulomatous area. c, d Atypical large cells show positivity for CD20. e, f An atypical large cell positive for CD30. f Reed-Sternberg (R-S)-like cells show positivity for CD30. g, h Similarity, nuclei of large round atypical cells are markedly positive for Ki-67 (labeling index exceeding 60–70%)

Fig. 5.

Detection of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in the re-biopsy specimen. a Immunohistochemically, EBV-LMP-1-positive cells are present in small foci of granuloma (original magnification × 400). b In situ hybridization for EBV shows strong staining in the nuclei (original magnification × 400)

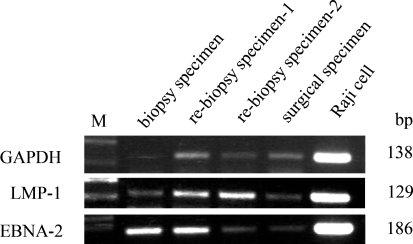

Using PCR, LMP-1 and EBNA-2 were detected in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections of each of the samples (biopsy, re-biopsy, and surgical), using Raji cells as a positive control (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

PCR analysis of the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) gene using formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. LMP-1 (129 bp) and EBNA-2 (186 bp) were detected in each of the specimens (biopsy, re-biopsy and surgical), and these bands showed the same levels in the Raji cells used as a positive control

Discussion

RA patients have an increased risk of developing hematopoietic and other malignancies, regardless of the immunosuppressive therapy they receive [13, 14], and recently the numbers of reported lymphomas have been increasing in RA patients receiving MTX [3]. Immunosuppression is known to predispose patients to EBV-related lymphomas. Approximately 50% of MTX-LPDs are EBV-positive [3]. EBV is associated with a number of malignant lymphomas, including Burkitt lymphoma, CHL and immunodeficiency-associated LPDs, Hodgkin-like lesions, and a subset of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. The number of EBV infections has also been increasing in patients with CHL and Hodgkin-like lesions [15]. In RA patients receiving MTX therapy, CHL has a CD30(+), CD20(−), CD15(+), EBV(−) immunophenotype, whereas most Hodgkin-like lesions are CD30(+), CD20(+), CD15(−), EBV(+), being positive for EBV by in situ hybridization [8, 10]. The present case lacked expression of CD15 in the CD30-positive Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS)-like cells and was the EBV(+) (LMP-1) type, or so-called Hodgkin-like lesion. MTX cannot be ruled out as a factor responsible for lymphoma in RA patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy. In MTX-associated EBV-LPDs, the lack of expression of CD15 in CD30-positive HRS-like cells has also been considered a feature that is not diagnostic of Hodgkin lymphoma [10]. Age-related EBV-LPDs were higer positivity (100%) for CD20, LMP-1, and lack (0%) of expression of CD15 [16]. Age-related EBV-LPD have higher has a poorer prognosis than EBV-positive CHL [16]. Thete is a significant difference in patient age and prognosis between age-related EBV-LPDs and iatrogenic immunodeficiency-LPDs, including those due to MTX. Age-related EBV-LPDs show no evidence of immunosuppression and tend to occur in patients older than 60 years, many of whom relapse and die in spite of chemo-radiationtherapy [8]. Iatrogenic immunodeficiency-LPDs, including those due to MTX, usually regress upon withdrawal of the drug and are considered attributable to a toxic/metabolic effect rather than being EBV-related. Recent descriptions of relapsed Hodgkin lymphomas, shown to be EBV-positive at initial diagnosis but EBV-negative at recurrence, raise the possibility that DNA is lost during tumor progression in some individuals [17, 18]. Overall, however, approximately 60% of reported cases have shown at least partial regression in response to withdrawal of MTX, the majority being EBV-positive cases [3]. Survival ratios are higher for patients with Hodikin lymphoma than for those with Hodgkin-like lesions [10].

The mechanism by which MTX increases the propensity of RA patients for development of lymphomas is not entirely clear. Menke et al. [5] have reported that cell dysregulation as measured by p53 protein expression and EBV-related transformation play important roles in the pathogenesis of lymphomas arising in patients with connective tissue disease who are immunosuppressed with MTX. In the present case, it was unclear why the lymphoma cells infiltrated into the oral cavity. This case was similar to another we have reported previously [7] in that the site of lymphoma infiltration coincided with severe periodontitis in the oral cavity. Sato et al. [19] have reported an abnormally high frequency of EBV-infected B cells in the peripheral blood of patients with RA. The factor responsible for lymphoma infiltration into the oral submucosal stroma is unclear, but there may have been an association with bacteria around the teeth in areas of periodontitis. There may be a relationship between EBV-infected B cells and the presence of periodontal bacteria. A recent study has shown that the including of lymphoma is increased in RA patients receiving anti-TNF treatment [20].

More studies, including reports of cases in the oral cavity, will be needed to confirm the causal link between MTX and LPDs in RA patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy.

We have reported a case of extranodal MTX-LPD showing a Hodgkin lymphoma-like feature in the oral cavity of a patient with RA. Very few such cases have been reported in the English literature [6–8]. Although MTX is thought to cause LPDs in RA patients, little is known about the histological pattern of the lesions. It will be important to accumulate and evaluate many cases of MTX-LPD and examine their clinical correlates, as well as their immunohistochemical and genotypic characteristics.

References

- 1.Daniel M, Knowles MD. Immunodeficiency-associated lymphoproliferative disorders. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:200–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tishler M, Caspi D, Yaron M. Long-term experience with low dose methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1993;13:103–106. doi: 10.1007/BF00290296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salloum E, Cooper DL, Howe G, et al. Spontaneous regression of lymphoproliferative disorders in patients treated with metotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1943–1949. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariette X, Cazals-Hatem D, Warszawki J, et al. Lymphomas in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with methotrexate: a 3-year prospective study in France. Blood. 2002;99:3909–3915. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.11.3909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menke DM, Griesser H, Moder KG, et al. Comparison of p53 protein expression and latent EBV infection in patients immunosuppressed and not immunosuppressed with methotrexate. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:212–218. doi: 10.1309/VF28-E64G-1DND-LF94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kojima M, Itoh H, Hirabayashi K, et al. Methotrexate-associated lymphoproliferative disorders: a clinicopathological study of 13 Japanese case. Pathol Res Pract. 2006;202:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka A, Shigematsu H, Kojima M, et al. Methotrexate-associated lymphoproliferative disorder arising in a patient with adult Still’s disease. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:1492–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dojcinov SD, Venkataraman G, Raffeld M, et al. EBV positive mucocutaneous ulcer—a study of 26 cases associated with various sources of immunosuppression. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:405–417. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181cf8622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uneda S, Sonoki T, Nakamura Y, et al. Rapid vanishing of tumors by withdrawal of methotrexate in Epstein-Barr virus-related B cell lymphoproliferative disorder. Inter Med. 2008;47:1445–1446. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamel OW, Weiss LM, Rijn M, et al. Hodgkin’s disease and lymphoproliferations resembling Hodgkin’s disease in patients receiving long-term low-dose methotrexate therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1279–1287. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee MA, Hong YS, Kang JH, et al. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus by PCR and expression of LMP1, p53, CD44 in gastric cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 2004;19:43–47. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2004.19.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CH, Liu HC, Hung TT, et al. Possible roles of Epstein-Barr virus in Castleman disease. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas E, Brewster DH, Black RJ, et al. Risk of malignancy among patients with rheumatic conditions. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:497–502. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001101)88:3<497::AID-IJC27>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silman AJ, Petrie J, Hazleman B, et al. Lymphoproliferative cancer and other malignancy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with azathioprine: a 20-year follow-up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:988–992. doi: 10.1136/ard.47.12.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gandhi MK, Tellam JT, Khanna R. Epstein-Barr virus-associated Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2004;125:267–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asano N, Yamamoto K, Tamaru J, et al. Age-related Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders: comparison with EBV-positive classic Hodgkin lymphoma in elderly patients. Blood. 2009;113:2629–2636. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-164806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delecluse HJ, Marafioti T, Hummel M, et al. Disappearance of the Epstein-Barr virus in a relapse of Hodgkin’s disease. J Pathol. 1997;182:475–479. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199708)182:4<475::AID-PATH878>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nerurkar AY, Vijayan P, Srinivas V, et al. Discrepancies in Epstein-Barr virus association at presentation and relapse of classical Hodgkin’s disease: impact on pathogenesis. Annal Oncol. 2000;11:475–478. doi: 10.1023/A:1008363805242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tosato G, Steinberg AD, Yarchoan R, et al. Abnormally elevated frequency of Epstein-Barr virus-infected B cells in the blood of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:1789–1795. doi: 10.1172/JCI111388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolfe F, Michaud K. The effect of methotrexate and anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy on the risk of lymphoma in rheumatoid arthritis in 19, 562 patients during 89, 710 person-years of observation. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1433–1439. doi: 10.1002/art.22579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]