Abstract

A 13-month-old Japanese boy presented with painless swelling in a left mandible and cheek. Intraoral examination revealed swelling in the left mandible and hemorrhage of oral mucosa due to biting. CT images revealed a wide osteolytic lesion of the left mandible with floating teeth. Biopsy was carried out and histopathological diagnosis was discussed.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Mandible, CD1a

Clinical Presentation

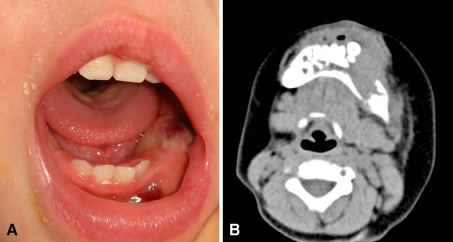

A 13-month-old Japanese boy was admitted to the Department of Pediatric Dentistry, and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Tokyo Dental College Chiba Hospital in March 2010, with a painless swelling in a left mandible and cheek. His parents noticed the symptom for a few months prior to admission. The patient was otherwise healthy, and with no significant past medical history. The family history was also unremarkable. Intraoral examination revealed swelling in the left mandible and hemorrhage of oral mucosa due to biting (Fig. 1a). CT images revealed a wide osteolytic lesion of the left mandible with floating teeth. The cortex of the mandible was destructive and adjacent soft tissue was involved by the mass (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Oral examination. The swelling in the left mandible is seen with hemorrhage due to biting of oral mucosa b Axial computed tomography image reveals a wide osteolytic lesion of the left mandible with floating teeth. The cortex of the mandible was destructive and adjacent soft tissue was involved by the mass

Differential Diagnosis

Based upon clinical and radiological findings, a quite wide list of possible diagnoses (Table 1) was considered although several could be excluded quite easily.

Table 1.

Possible differential diagnosis

| Infection |

| Fibro-osseous lesion |

| Tumours |

| Ewing’s sarcoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumour (ES/PNET) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Neuroblastoma |

| Melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy |

| Leukaemia |

| Lymphoma |

| Odontogenic tumour |

| Aggressive central giant cell granuloma |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

Infection (osteomyelitis) was deemed unlikely on the basis that the mass was homogenous without areas of heterogenous soft. A benign fibro-osseous lesion was thought to be unlikely given that the radiological features pointed to a rapidly growing lesion. In addition, there was no evidence of mineralization within the soft tissue mass. Given the age of the patient and again, seemingly rapid growth, a benign odontogenic tumor was thought to be highly unlikely.

Childhood leukaemias and lymphomas tend to present in children that are slightly older, the most common types in the paediatric population being acute lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia/lymphoma is a disease of younger children with 75% of cases presenting in children <6 years old andut most will have symptoms relating to bone marrow failure [1]. On the basis of the clinical photographs, which showed clear lack of pigmentation and mandibular lesion, a diagnosis of melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy was generally eliminated from the list of differential diagnoses.

Aggressive giant cell granuloma was considered a more likely possibility and has previously been described in an 18-month-old patient and in an anterior mandibular location [2]. This case showed, in contrast to the present case, bony expansion and a periosteal reaction and there appeared to be more limited soft tissue swelling.

Malignant childhood tumours were also high on the list of differential diagnoses and included Ewing’s sarcoma/Primitive neuroectodermal tumour (ES/PNET), rhabdomyosarcoma and metastatic neuroblastoma and in favour of these were the radiological features of a rapidly growing lesion with no expansion or periosteal reaction and with a significant soft tissue component. Ewing’s sarcoma (ES) is a tumour affecting predominantly children and adolescents but only rarely seen in patients less than 5 years in age [3]. Immunohistochemical and, more importantly, cytogenetic studies have established that the primitive neuroectodermal tumour of infancy (PNET) is within the same spectrum. The head and neck is one of the commonest sites for rhabdomyosarcoma with a peak age of diagnosis less than 4 years of age [3], with the embryonal subtype affecting younger patients. There are cases described arising in a mandibular location [4], which document severe bone destruction. Both ES and rhabdomyosarcoma were considered strong possibilities. Several case reports of metastatic neuroblastoma to jaws exist in the literature [5] and this was also considered a possibility although a rare phenomenon.

The clinical description of floating teeth was strongly in favour of a diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis and the age of the patient was in-keeping with this as the peak age of diagnosis in children is reported as 1–3 years [6]. In the present case, the degree of soft tissue involvement almost seemed to exceed the amount of intraosseous involvement, but Schmidt et al. [7] describe a similar case to ours with a significant extraosseous soft tissue component. These authors also comment that extraosseous involvement is much less frequently seen than osseous disease leading to difficulties in radiolological diagnosis but given the similarities between our case and that of a temporo-occipital lesion described in this paper, we felt it important to include this entity in the differential diagnosis.

Taking into account the clinical history and imaging, the favoured diagnosis was of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Diagnosis and Discussion

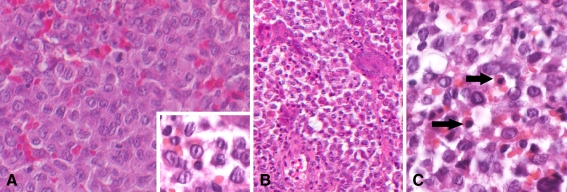

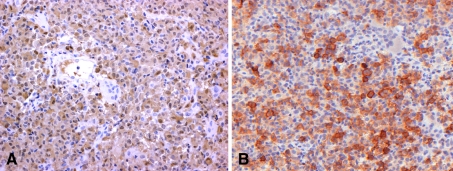

The first deciduous molar in the left mandible was clinically floating, and biopsy was carried out with extraction. Histopathologically, numerous eosinophilic cells were diffusely proliferating with scanty fibrous stroma (Fig. 2a). At higher magnification, the proliferating cells had indented and folded or grooved nuclei resembling coffee beans (Fig. 2a), and nuclear chromatin was finely dispersed. Mitoses were occasionally observed in the proliferating cells. Multinuclear giant cells were frequently seen (Fig. 2b). Eosinophils and neutrophils were admixed with the proliferating cells (Fig. 2c), but plasma cells were rare. The main cells were positive for S-100 protein (Fig. 3a), while multinuclear giant cells were negative. The main cells were negative for CD68, which is a marker for monocyte/macrophage, but in contrast, the multinuclear giant cells were positive for CD68, suggesting the main cells were not derived from monocyte/macrophage. Also, the main cells were positive for CD1a, which is a specific marker of Langerhans cell (Fig. 3b). Keratin, myogloblin, factor VIIIa and CD99 were negative. Interestingly, vimentin was weakly positive. Ki-67 labeling index was 19.2%. Finally, histopathological diagnosis of Langerhans cell histocytosis (LCH) was rendered.

Fig. 2.

a Numerous eosinophilic cells are diffusely proliferating with scanty fibrous stroma. At higher magnification, the proliferating cells have grooved nuclei resembling coffee beans, and nuclear chromatin is finely dispersed (inset). Mitoses are occasionally observed in the proliferating cells b Multinuclear giant cells are frequently seen c Eosinophils (arrows) and neutrophils are admixed with the proliferating cells

Fig. 3.

a Immunohistochemically, the main cells are positive for S-100 protein, while multinuclear giant cells are negative b The main cells show immunoreaction for CD1a, which is a specific marker of Langerhans cell

LCH is defined as neoplastic proliferation of Langerhans cells, and was formerly referred to as three overlapping lesions; eosinophilic granuloma of bone, Hand-Schuller-Christian disease and Letterer-Siwe disease, and now these lesions are recognized as clinical variants of LCH [8].

LCH occurs mostly in children, and the incidence is five per million [6]. Male/Female ratio is about 3.7–1. Generally, the lesion occurs in bone (skull) and skin, and pain and swelling of affected area are main symptoms. Otorrhea and facial swelling are well observed in affected area of head and neck. As radiological findings, lytic and destructive bone lesions are seen, and bone lesions are associated with adjacent soft tissue masses.

Biopsy is necessary to diagnose LCH. Histopathologically, folded or grooved nuclei resembling coffee beans and indented nuclei are typical findings. Eosinophils, lymphocytes and neutrophils are usually admixed with proliferating Langerhans cells, and multinucleated giant cells can be identified. Immunohistochemistry is important to diagnose and to exclude differential diagnosis. Immunohistochemically, the cells of LCH are positive for S-100 protein and CD1a, which are markers of Langerhans cell [8, 9], but negative for CD68, suggesting the main cells have a character of Langerhans cells, but not of histiocytes. Ki-67 ratio ranges from 2 to 25%, and a study on prognosis, however, demonstrated that an increased mitotic rate did not correlate with prognosis [10]. Moreover, Birbeck granule is definitive ultrastructural finding for diagnosis.

Single agent chemotherapy produced a good response in significant percent of LCH patients, although recurrence is typically seen in over half of the cases[11]. A combination of vincristine and predonisone seems to reduce this risk of recurrence. In this case, chemotherapy with corticosteroid, cytarabine, vincristine, and methotrexate was selected, because of the age and wide affected area. There was no sign of recurrence at 8 months post-chemotherapy, and follow-up continues.

Prognosis is associated with age of patients. In general, the prognosis is poorer for LCH patients in whom the first sign of the disease develops at very young age and better for LCH patients who are older at the time of onset [11]. Moreover, clinical outcome is also associated with number of organs affected [12]. Survival rate is about 95% when only a single site is affected, but drops down to 75% if there are two affected organs [13]. Chronic disseminated LCH is often associated with considerable morbidity, but few patients die as a result of the disease. Diffuse LCH with compromise of multiple organs is associated with poor prognosis and is often fatal [11].

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Tsukasa Sano and Dr. Jun-ichiro Sakamoto for providing CT images of this lesion, and Prof. Takahiko Shibahara, Dr. Chihaya Ikeda (Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Tokyo Dental College) and Prof. Seikou Shintani (Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Tokyo Dental College) for their taking care of the patient.

References

- 1.Swerdlow S. CE, Harris N.: WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4. Lyon: IARC; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vered M, Bello IO, Salo T, et al. Clinico-pathologic conference AAOMP/IAOP : case 3. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:283–288. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0079-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fletcher C. Diagnostic Histopathology of tumors. 3. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gordon-Nunez MA, Piva MR, Dos Anjos ED, et al. Orofacial rhabdomyosarcoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E765–E769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilcox PB, Wright JM, Byrd RL. Metastatic neuroblastoma to the jaws: report of two cases. ASDC J Dent Child. 1984;51:211–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson HS, Egeler RM, Nesbit ME. The epidemiology of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:379–384. doi: 10.1016/S0889-8588(05)70517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmidt S, Eich G, Geoffray A. Extraosseous langerhans cell histiocytosis in children. Radiographics. 2008;28:707–726. doi: 10.1148/rg.283075108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieberman PH, Jones CR, Steinman RM, et al. Langerhans cell (eosinophilic) granulomatosis. A clinicopathologic study encompassing 50 years. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:519–552. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199605000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emile JF, Wechsler J, Brousse N, et al. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis. Definitive diagnosis with the use of monoclonal antibody O10 on routinely paraffin-embedded samples. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:636–641. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199506000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Risdall RJ, Dehner LP, Duray P, et al. Histiocytosis X (Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis). Prognostic role of histopathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1983;107:59–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neville BW. Oral and maxillofacial pathology volume 13. 3. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberger JS, Crocker AC, Vawter G, et al. Results of treatment of 127 patients with systemic histiocytosis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1981;60:311–338. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198109000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P. Sidransky D. WHO classification head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2005. [Google Scholar]