Summary

In 2006 a Department of Health Working Group on Arts and Health reported that the arts have ‘a clear contribution to make and offer major opportunities in the delivery of better health, wellbeing and improved experience for patients, service users and staff alike’. In this review we examine the evidence underpinning this statement and evaluate the visual art of three of Scotland's newest hospitals: the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, the new Stobhill Hospital, and the new Victoria Infirmary in Glasgow. We conclude that art in hospitals is generally viewed positively by both patients and staff, but that the quality of the evidence is not uniformly high. Effects may be mediated by psychological responses to colour hue, brightness and saturation. Colours that elicit high levels of pleasure with low levels of arousal are most likely to induce a state of calm, while those causing displeasure and high levels of arousal may provoke anxiety. The fact that patients frequently express a preference for landscape and nature scenes is consistent with this observation and with evolutionary psychological theories which predict positive emotional responses to flourishing natural environments. Contrary to a view which may prevail among some contemporary artists, patients who are ill or stressed about their health may not always be comforted by abstract art, preferring the positive distraction and state of calm created by the blues and greens of landscape and nature scenes instead.

Introduction

That the arts and sciences are seen as two contrasting disciplines, and indeed are defined as such, immediately presents challenges to a discussion of art in medicine, one of the foremost branches of science. There has, nevertheless, always been an awareness of the ‘art of medicine’ and a realization that health is influenced by a wide range of factors, many of which fall outside the conventional boundaries of medical science. As Kirsty Schirmer, Policy Officer of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health, argues, ‘broader determinants impact on health and … often art acknowledges these determinants where science cannot’.1 There is moreover increasing evidence that the display of visual art, especially images of nature, can have positive effects on health outcomes, including shorter length of stay in hospital, increased pain tolerance and decreased anxiety.2–5

The idea that art may have potential positive benefits in healthcare is not new and has been recognized by artists and healthcare professionals alike. The quotation ‘Art washes away from the

Box 2. Visual art in the new Stobhill Hospital.

The new Stobhill Hospital is an Ambulatory Care and Diagnostic Centre and opened in June 2009. In 2005 an Arts and Environment Working Group for the hospital was set up by Jackie Sands, Arts and Health Co-ordinator for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. The Working Group collaborated closely with architects and artists during the design phase of the hospital. They chose 'A Grove of Larch in a Forest of Birch' as their artistic theme to reflect the use of natural larch finishes within the hospital and the presence of many silver birch trees in the grounds. The visual art within the building consists of videos, paintings, window designs and drawings.

Videos – In all of the hospital's 15 waiting rooms are monitors displaying films recorded by Olwen Shone. The videos, different in every room, have landscape and nature themes such as the slow passing of clouds, ripples in a pool or gently waving branches of a tree. The issue this project has faced is that the nurses who run the waiting rooms have in some instances re-arranged the chairs. Changing the orientation of the chairs means that fewer of them face the installation, and patients are not exposed to the work in the intended manner.

Paintings – Walls in clinic areas known as 'programmable spaces' have been designated for the display of paintings, which can be supplied by organizations such as Art in Hospital, Art in Healthcare and Glasgow City arts and museums partners. The success of the programmable spaces is perhaps implicitly suggested by the complaints from staff from a clinic that lacks any paintings. The manager of a clinical area on the ground floor spoke of how staff felt this was 'too bleak'. This area had no visual art in it.

Window designs – In waiting rooms which overlook courtyards, the Latin names of trees are sandblasted on to windows. This idea was the subject of considerable debate at the planning phase. Some members of the Working Group felt that because the general population was unfamiliar with Latin then people would not engage positively with the words. However, the artist contended that the absence of meaning would give emphasis to the sound and rhythm of the words, giving them a poetic therapeutic quality (Figure 3).

Three Landscapes – In the waiting areas which have no external view, Donald Urquhart designed three artworks in response to texts by Scottish Poet Thomas A Clark. For example, the waiting room on the second floor has a painting of a tree (Figure 4).

An Alphabet – This is a series of 18 drawings, each with two panels. The left hand panel shows a single letter and the right hand panel has a drawing of a particular tree. Each letter is from the Gaelic alphabet, in which language the association of letters with trees is a traditional aid to teaching the alphabet to children. The original proposal for this project suggested that the works be wall mounted in a variety of locations throughout the hospital. However, the works were actually clustered on the third floor in an area that only staff use (Figure 5).

Staff room

This has a rotating exhibition of paintings, currently featuring work by patients. In future it will contain paintings from sources such as schools and community projects, selected and sourced by the Working Group. Staff seemed generally to approve of this exhibition but it is not seen by patients.

Evaluation of visual art

The Working Group does not currently have systematic feedback from patients and staff although a survey is being planned in conjunction with the Scottish Arts Council and NHS-GGC Public Health Research and Evaluation Department.

soul the dust of everyday life’ is usually attributed to Picasso. In 1859 Florence Nightingale recognized the importance of art in medicine and raised issues that are still highly relevant today. In Notes on Nursing she wrote ‘The effect of beautiful objects, of variety of objects and especially brilliance of colour is hardly at all appreciated … Little as we know about the way in which we are affected by form, by colour and light, we do know this, that they have an actual physical effect. Variety of form and brilliancy of colour in the objects presented to patients are actual means of recovery.’6 Hamish McDonald, an artist and cancer patient at the Beatson Hospital in Glasgow, offered a more contemporary view when he wrote ‘I am a firm believer in the power that art has to inspire and help alleviate suffering and that it can play a key role in lessening the burden that illness brings’. A display of his observations of life as a cancer patient hang in the atrium of the new Medical School Building in Glasgow.

The potential benefits to patients of visual art are also now also recognized by politicians and civil servants. In 2001 Alan Milburn, then Minister of Health, argued there should be ‘from the outset an appreciation of the importance of the patient environment to recovery and rehabilitation’.7 Following this in 2006 a Department of Health Working Group on Arts and Health concluded that the arts ‘have a clear contribution to make and offer major opportunities in the delivery of better health, wellbeing and improved experience for patients, service users and staff alike’. The report also stated that the arts should be recognized as being integral to health, healthcare provision and healthcare environments.8 This is a view echoed by Sunand Prasad, Commissioner of the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment who stated that ‘Good design must be a central consideration … and will ensure that the hospital provides a high-quality environment that supports a positive and healing experience. ’9

Our interest in this area stems from our enjoyment of visual art and our personal observation that the best paintings in hospitals are usually hung in non-clinical areas, while paintings in wards are either displayed haphazardly or not at all. Against this background we wanted to know what patients really liked looking at. We were particularly interested in the evidence that carefully chosen visual art might improve patient wellbeing or even outcomes. In an accompanying paper we present findings that support this view. Patients attending the Renal Transplant Clinic in Dumfries completed a questionnaire and rated the paintings we had chosen to display in the waiting area as one of the factors that contributed positively to their outpatient experience.10

Visual art and healthcare – the evidence base

Perhaps the best known scientific study of the visual environment and health outcomes is a retrospective analysis in which 23 patients recovering from cholecystectomies in rooms with windows on to natural settings rather than brick walls had shorter postoperative hospital stays, had fewer negative evaluative comments from nurses, took fewer moderate and strong analgesic doses and had slightly lower scores for minor postsurgical complications.11 In a randomized, controlled, cross-over trial of healthy volunteers, Tse et al. demonstrated an increased pain threshold and pain tolerance when participants were exposed to soundless video displays of nature as opposed to a blank screen.3 Visual images, which might be more easily incorporated into healthcare settings than videos or window views have also been studied. Levels of depression and anxiety tended to be lower in patients undergoing chemotherapy who were exposed to visual art than in patients not exposed to visual art.5 Nature themes were studied by Diette and colleagues in a randomized controlled trial of patients undergoing flexible bronchoscopy. They found that pain control was significantly better in the intervention group than in controls.4 Ulrich investigated the effects on patients recovering from open heart surgery of exposure to one of the following: an image of nature, an abstract image or no image. Patients exposed to the nature image experienced less postoperative anxiety than either of the other two groups. They were also significantly more likely to switch from strong analgesics to weaker painkillers during their recovery. Of note the patients exposed to an abstract image experienced more anxiety than those with no image.2

Art in hospitals is generally

Figure 3.

Latin names of trees – Thomas Clark

Figure 4.

Six landscapes – Donald Urquhart

viewed positively by both patients and staff. A qualitative evaluation of the Exeter Healthcare Arts Project found that the display of visual arts in that hospital was perceived by patients, staff and visitors to have a positive effect on morale. Forty-three percent of frontline clinical staff believed that the arts had a positive effect on healing and 24% considered that the arts improved clinical outcomes.12 Other studies have assessed the importance of patient choice. A volunteer program in Canada allowed long-term hospital patients to choose from a selection of artworks the one which they would like displayed in their room. Patients reported that the added element of choice improved their mood.13 There is, moreover, considerable evidence that mental health can be improved by participation in arts projects (see www.artfull.org ). We felt this particular, yet important, aspect of the visual art evidence base was outwith the scope of our remit and do not discuss it further here.

While studies such as the ones we have described do provide evidence that visual art may have positive effects on patient wellbeing and health outcomes, the quality of the evidence is not uniformly high. The authors of one systematic review assessing the impact of art, design and environment in mental healthcare concluded that none of the papers would have met the inclusion criteria used by systematic reviews such as the Cochrane Collaboration.14 Common problems observed in this type of research are lack of control groups, lack of randomization, lack of blinding, missing data and failure to report or perform power calculations.

Possible mechanisms of benefit

Positive distraction

It has been proposed that the beneficial effects of visual art on health are due to positive distraction. Positive distraction is a term used to describe the belief that environmental features can elicit positive feelings, hold attention and interest and, therefore, reduce stressful thoughts. This idea has been developed by Malenbaum and colleagues in a review for the International Association for the Study of Pain. These authors regard a typical treatment setting as one that lacks any positive distraction and argue that environmental stimuli, including visual art, may enhance patient control.15 Conversely environments that lack positive distractions may cause patients to focus increasingly on their own worries, fears or pain. This can increase the perception of these emotions, and in turn increase levels of stress.15,16 There is already a body of literature relating to the deleterious effects of stress on health, and it is suggested that the positive effects of visual art may be due in part to stress reduction.16,17

Effects of colours on emotions

There is a large

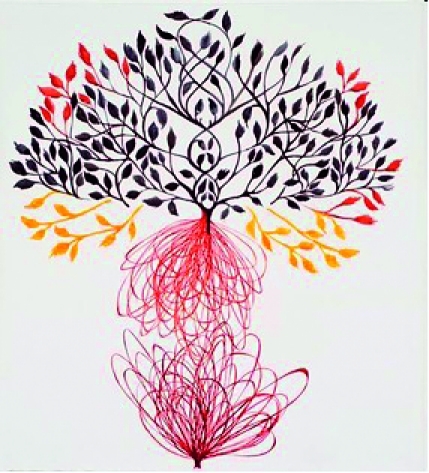

Figure 5.

An alphabet – Donald Urquhart

Figure 6.

Coloured glazing – Ally Wallace

body of literature on effects of colours on emotion, and it is possible that the colours used in visual arts are part of the mechanism of benefit. Briefly, colour stimuli may be characterized by hue (wavelength), brightness (illumination) and saturation (vividness); and our emotional responses to these stimuli as pleasurable/non-pleasurable and arousing/not arousing. Colours that elicit high levels of pleasure with low levels of arousal are most likely to induce a state of calm, whereas those causing displeasure and high levels of arousal may provoke anxiety.18 The short wavelength blues and greens generally elicited more pleasure than the longer wavelength reds and yellows in the comprehensive study by Valdez and Mehrabian, while no consistent patterns were observed between hue and arousal. Brighter and more saturated colours were more pleasant, with brightness contributing more to pleasure than saturation. By contrast, saturation contributed more to arousal than did brightness.18 Jacobs and Suess investigated the effects of red, yellow, green and blue projected on to a large screen and showed higher state-anxiety scores with red and yellow than with blue and green, though to our knowledge no attempt was made to control for brightness and saturation in that study.19 A similar study monitoring physiological variables showed greater increases in heart rate and respiratory rate with red and yellow than with blue and green.20 We conclude that colour may be one of the reasons why patients prefer paintings depicting nature scenes, since these are often dominated by blue and green.

Visual art in the new Edinburgh and Glasgow Hospitals

Caspari and colleagues evaluated the number of Norwegian hospitals that had included an aesthetic dimension in their business plans. They concluded that this aspect of hospital design is often overlooked.21 No comparable assessment of UK hospital business plans has been performed. Against this background we conducted an evaluation of the visual art in three new Scottish hospitals: the new Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh which opened in 2003 and the new Stobhill and Victoria Hospitals in Glasgow which opened in 2009. A key feature of the design of all three hospitals was the input of artists at an early stage allowing the incorporation of visual art from the beginning of the design process.

A description of the visual art in the new Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh and the new Stobhill and Victoria Hospitals in Glasgow is summarized in Boxes 1–3 and Figures 1–8. Each hospital appointed an Arts Committee or Working Group to develop an arts strategy. Each has employed a variety of visual approaches, some traditional and some contemporary.

Figure 7.

Sculpture Garden – Calum Stirling

Most of the visual art in these hospitals has been placed in public areas including foyers, corridors and waiting rooms. Informal feedback to the authors from staff and patients thus far has generally been positive. Most, however, appear to prefer landscape and nature scenes to abstract work, in keeping with the evidence described earlier in this review. Particularly successful has been Deirdre Nelson's Arcadia Project in Edinburgh, a series of images based on the memories of elderly patients at interview (Figure 2) and ‘Trees and Their Reflections’ at the new Victoria Hospital in Glasgow in which artist Hanneline Visnes has decorated the walls of waiting areas with murals that draw their imagery from nature such as birds and plants (Figure 8). None of the three hospitals have as yet evaluated the impact of their visual art on patients and staff, although the new Stobhill and Victoria Hospitals plan to do so. The architects of the new Stobhill project have already been commended for their achievement in creating ‘A nice hospital, a quiet place that could help and calm people’.22

Box 1. Visual Art in the New Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE).

The new RIE was opened in 2003. It has a Voluntary Arts Committee, established in 1997 and chaired by Sandy Young. Visual art in public areas including foyer, corridors and mall is controlled by the Arts Committee:

Inscribables – Scottish Artist Shona McMullen asked staff of the old Royal Infirmary ‘What lasting memory or impression of your old workplace would you like to take with you to the new Royal Infirmary?’ The answers she received are embedded in the artwork installed along the north corridor of the ground floor. This has been popular among staff, and includes the old table tops from the Doctors' Mess at the old Infirmary which are mounted on the wall covered in engravings of doctors names inscribed over the years, while on the other side of the corridor wall are: evocative quotes from staff who worked in the old hospital.

Life Rules Over Historic Ground – in which cellular formations depicting scientific thought are overlaid or placed alongside archival photographs of the old Royal Infirmary. The artist intended the cellular formations to act as a metaphor, highlighting the significance of scientific research and its far-reaching impact on medical practice. This installation has received a rather mixed response from patients and staff, some seeming to prefer the historic photographs unaltered, others appreciating the contemporary presentation of historic images in the new hospital setting.

Milestones – Patients and staff were asked to describe ‘milestones on their journey’ and to bring rocks to the artist Samantha Clark who sandblasted single words or short phrases on to each rock and then displayed the rocks in cavities built into walls next to lifts (Figure 1). The patients and staff who participated in the project spoke positively about it, whereas patients who merely saw the project in passing said they found it confusing and abstract.

Arcadia – A series of images based on the memories of elderly patients at interview. These images depict well-known locations around Edinburgh in black and white onto which memories are printed and embroidered in colour (Figure 2). Memories include days out at the beach, flowers, birds, trees, football and dancing. This project by Deirdre Nelson has received much praise and support from patients and staff alike.

Pelican Gallery – This consists of artwork by staff and patients, touring exhibitions and art selected from nearby communities. The majority of painting depicts landscapes or nature scenes and many of the works are on sale. It has proved very popular.

Other examples – There are some purchased works in hospital corridors, including a painting of a large red cross with a dead fish at each end of the cross. This attracted negative comments from patients with some taking exception to the perceived religious imagery and others simply finding it aesthetically unpleasant. Various paintings by Edinburgh College of Art graduates also adorn the walls. These have not met with universal approval, possibly reflecting their abstract nature.

Wards and waiting rooms

The choice of visual art within wards and waiting rooms in the new RIE is sometimes determined by the local staff team. There is much variation from ward to ward, but most waiting rooms have paintings. Staff are aware of the existence of the Arts Committee and have on occasion approached the committee for help procuring artwork, which the committee is happy to provide. Ward paintings often come from the organization Art in Healthcare (formerly Paintings in Hospitals).

Evaluation of visual art

Though all projects have involved a consultation with hospital staff while a brief is being created, there has been no formal attempt to evaluate the impact of the visual art project in the new RIE.

Box 3. Visual Art in the New Victoria Hospital.

The New Victoria hospital is an Ambulatory Care and Diagnostic Centre and opened in June 2009. In 2005 an Arts and Environment Working Group for the hospital was set up by Jackie Sands, Arts and Health Co-ordinator for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. The group went on to oversee the commissioning of a curator and lead artist who worked closely with HLM Architects in the planning of integrated art and architecture elements. An outline healing arts strategy was created, along with a lead artist brief and additional artist briefs for developing art works in the courtyard, hospital entrance atrium, main circulation routes, car park, Spiritual Care rooms, staff dining area and waiting areas. The original and unifying main theme for the project is 'the Hospital in the Park'. The resulting visual artwork consists of the following projects;

Coloured Glazing – lead artist Ally Wallace chose panels of coloured glass to replace a small number of the standard glass panels which make up the many large windows of the hospital. These exist throughout the hospital and are intended not just to look attractive in their own right but also to illuminate spaces with a carefully selected palette (Figure 6).

Programmable spaces – One wall in every waiting area has been highlighted as a programmable space for art. In some cases these spaces are used by artists given a brief for the project and in others they are filled by paintings from the charity 'Art in Hospital'. Some staff members have mentioned that alongside paintings they would appreciate an accompanying plaque with some information.

Sculpture Garden – titled 'Thresholds and Prospects', a sculpture garden was developed by Calum Stirling inspired by diverse natural sources such as the Scottish Highlands and Japanese rock gardens (Figure 7). It involves seating and architectural spaces and acts as an 'aesthetic habitat' for hospital users. Unfortunately, it has had some criticism from patients and even a newspaper. The concern of critics is that it is not a good use of money, despite not being funded from the hospital budget.

Murals – artist Hanneline Visnes created a series of murals through a number of waiting areas (Figure 8). They cover relatively large areas of wall and draw imagery from nature, such as birds and plants. These have been very well received for their colours, novelty and fine detail. While touring a clinic, one member of staff even expressed a light-hearted envy that their clinic didn't have a mural.

Seed Pods – other waiting areas feature tissue paper sculptures mounted on the walls in display cases. These are the work of Jackie Parry, who took tiny components of trees and flowers and made much larger versions. Staff reported that patients would often ask what they were, and would not receive an explanation since staff had no idea either. Staff suggested explanations would be very helpful and that in the current format the sculptures do not improve the waiting rooms.

Video projection wall – in the hospital atrium a projector is mounted to project large scale images onto the wall. Currently displayed is a kaleidoscope slide show of images of Victoria Park.

Car park

Various coloured designs have been painted onto the walls of the underground car park. These are intended to aid people in locating their cars and to improve the aesthetic of the area, which may be the first point of contact with the hospital for many patients and visitors.

Evaluation of visual art

The Working Group does not currently have systematic feedback from patients and staff although a survey is being planned in conjunction with the Scottish Arts Council and NHS-GGC Public Health Research and Evaluation Department.

Figure 1.

Milestones on their journey – Samantha Clark

Figure 2.

Memories – Deirdre Neilson

Figure 8.

Murals – Hanneline Visnes

Discussion

Main findings

In this paper we have reviewed evidence demonstrating the benefits to patients of displaying visual art in hospitals. These include positive effects not only on patient wellbeing but also on health outcome such as length of stay in hospital and pain tolerance. Our own observations on the artwork in three new Scottish hospitals reinforce this view, with many fine examples of visual art being used to good effect. There were also some less successful projects. Given that much of the evidence in this area is still of poor quality, further work is necessary. It is to be hoped that the planned evaluations of the artwork in two of the three Scottish hospitals studied will add to the evidence base.

That patients frequently express a preference for landscape and nature scenes2–4 is consistent with certain evolutionary psychological theories, which predict positive emotional responses to flourishing natural environments. The so-called biophilia hypothesis suggests that the ability to recognize healthy natural environments is a survival advantage, since these environments provide the best resources. This ability has, therefore, been inevitably encouraged by natural selection during the evolution of modern humans and is rewarded with positive emotional responses.23 Another possible reason why patients prefer paintings depicting nature scenes may be related to colour. Nature scenes are often dominated by blues and greens, the colours shown to elicit more pleasure and less arousal than reds and yellows.18,20

Limitations

Our paper has several limitations. We acknowledge that the evidence base regarding visual art in hospitals is not of uniformly high quality, has many gaps, and relies too heavily on anecdote and personal perspectives.12,24 Further limitations arise from looking at an area with as many complexities as art. One could interpret the work of Ulrich2 as suggesting that there is a hierarchy of impacts with images of nature being preferable to no images which in turn are preferable to abstract images. The danger in interpreting the research in this way is that over-simplified hierarchies may be derived, while diversity and complexity are ignored. It is likely, for example, that different types of abstract art will elicit different emotional responses in the same person.

We are also conscious of the fact that in attempting to describe the impact of visual art in three Scottish hospitals we have isolated one element of each hospital's artistic whole in a way that was not intended. The new Stobhill Hospital, for example, has a rich diversity of artistic elements: long views to the Campsie hills; courtyards planted with larch, grasses and ivys; videos of woodland scenes from Perthshire, some 50 miles away; paintings of natural scenes; drawings of elements of trees, and text works conjuring up natural scenes in the mind through words. To concentrate solely on visual art risks over-simplifying what is clearly a much more complex and bigger picture.

Implications

These caveats notwithstanding, the assumption that the display of visual art is not relevant as long as the level of care is good, seems likely to be wrong. Many complex factors are known to influence health and wellbeing and, as levels of care improve, the importance of less easily quantifiable factors will likely increase. This is acknowledged by Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs theory. As more basic needs are met, for example by new drugs and treatments, those needs higher up the hierarchy, which include the visual environment, will assume greater importance.25

While projects, such as the Edinburgh and Glasgow new hospitals, in which the artist works directly with architects and planners can be successful, another means of increasing art in hospitals is by renting it. The Scottish-based Art in Healthcare (see www.artinhealthcare.org.uk ) is a charity with a library of many different original artworks which it leases to hospitals, allowing hospitals to display artwork without having to specifically commission them. Other organizations work on a similar basis. Of note is Art in Hospital, which provides an extensive programme of visual arts in a variety of healthcare settings in the city of Glasgow and Scotland-wide (see www.artinhospital.org ).

Conclusions

We conclude that visual art in hospitals can provide medical benefits to patients, but that the quality of the evidence is not uniformly high. Effects may be mediated by psychological responses to colour hue, brightness and saturation. Colours that elicit high levels of pleasure with low levels of arousal are most likely to induce a state of calm, while those causing displeasure and high levels of arousal may provoke anxiety. The fact that patients frequently express a preference for landscape and nature scenes is consistent with this observation and with evolutionary psychological theories which predict positive emotional responses to flourishing natural environments. We also conclude that if art is considered an integral part of hospital design, as in the hospitals we studied, this will maximize these benefits. Contrary to a view which may prevail among some contemporary artists, patients who are ill or stressed about their health may not always be comforted by abstract art, preferring the positive distraction and state of calm created by the blues and greens of landscape and nature scenes instead.

Footnotes

DECLARATIONS —

Competing interests None declared

Funding A small grant from our Health Board enabled us to commission photographs of visual arts in the new Stobhill and new Victoria Hospitals

Ethical approval Not applicable

Guarantor CI

Contributorship CI conceived the idea, LL and PC wrote the first draft and all four authors contributed to the final draft

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jackie Sands, Arts and Health Co-ordinator for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clydeand Sandy Young, Chair of Voluntary Arts Committee for the new Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh for their advice during the preparation of this paper, Luigi di Pasquale for the photographs in Figures 3–7; and Josephine Campbell for typing the manuscript

References

- 1.Schirmer K. News. J Roy Soc Promot Health 2006;126:99–108 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulrich RS, Lunden O. Effects of exposure to nature and abstract pictures on patients recovery from heart surgery. Psychophysiology 1993: S1: 7 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tse MM, Ng JK, Chung JW, Wong TK. The effect of visual stimuli on pain threshold and tolerance. J Clin Nurs 2002; 11: 462–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diette GB, Lechtzin N, Haponik E, Devrotes A, Rubin HR. Distraction therapy with nature sights and sounds reduces pain during flexible bronchoscopy: a complementary approach to routine analgesia. Chest 2003;123:941–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staricoff R, Loppert S. Integrating the arts into healthcare: can we effect clinical outcomes? In: Kirklin D, Richardson R, eds. The Healing Environment: Without and Within. London: RCP; 2003. pp. 63–79 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nightingale F. Notes on nursing: what it is and what it is not. London: Harrison; 1859 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gesler W, Bell M, Curtis S, Hubbard P, Francis S. Therapy by design: evaluating the UK hospital building program. Health Place 2004;10:117–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cayton H. Report of the Review of Arts and Health Working Group. London: Department of Health; 2007. See http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_073590 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment. Radical improvements in hospital design. Healthy Hospitals campaign report 2003. See http://www.cabe.org.uk/publications/radical-improvements-in-hospital-design .

- 10.Cusack P, Lankston L, Isles C. Impact of visual art in patient waiting rooms: survey of patients attending a transplant clinic in Dumfries. J R Soc Med Sh Rep 2010; doi: 10.1258/shorts.2010.010077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ulrich R. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984;224:420–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scher P, Senior P. Research and Evaluation of the Exeter health care arts project. Med Hum 2000;26:71–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suter E, Baylin D. Choosing art as a complement to healing. Appl Nurs Res 2007;20:32–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daykin N, Byrne E, Soteriou T, O'Connor S. The impact of art, design and environment in mental healthcare: a systematic review of the literature. J R Soc Promot Health 2008;128:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malenbaum S, Williams AC, Ulrich R, Somers TJ. Pain in its environmental context: implications for designing environments to enhance pain control. Pain 2008;134:241–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ulrich RS. Effects of interior design on wellness: theory and recent scientific research. J Health Care Inter Des 1991;3:97–109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brannen C, Johnson Emberly D, McGrath P. Stress in rural Canada: A structured review of context, stress levels, and sources of stress. Health Place 2009;15:219–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valdez P, Mehrabian A. Effects of color on emotions. J Exp Psychol Gen 1994;123:394–409: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs KW, Suess JF. Effects of four psychological primary colors on anxiety state. Percept Mot Skills 1975;41:207–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs KW, Hustmyer FE. Effects of four psychological primary colors on GSR, heart rate and respiration rate. Percept Mot Skills 1974;38:763–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caspari S, Eriksson K, Nåden D. The aesthetic dimension in hospitals – an investigation into strategic plans. Int J Nurs Stud 2006;43:851–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glendinning M. Ennobling the ordinary? In: Law A, Dominiczak M, Ottar A, Clark T, Masser S, eds. Space to Heal: Humanity in Healthcare Design. Edinburgh: Sleeper; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson EO. Biophilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staricoff R. Arts in health: a review of the medical literature. Manchester: Arts Council England; 2004. See http://www.nasaa-arts.org/nasaanews/B-Health-MedLitReview.pdf .

- 25.Devlin A, Arneill A. Health care environments and patient outcomes. A review of the literature. Environ Behav 2003; 35:665–94 [Google Scholar]