Abstract

Members of the tumour necrosis factor superfamily play an essential role in inducing various biological responses including proliferation, differentiation, survival and cell death. A proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL), first identified as a stimulant of tumour proliferation, is now known as a regulator of B-cell-mediated immune responses through the modulation of B-cell survival and activation. However, the role of APRIL in macrophage function has not been explored. High level expression of APRIL was detected on the surface of cells of the monocytic lineage including the human macrophage-like cell line, THP-1. To identify the role of APRIL in macrophage functions, THP-1 cells were stimulated with either its counterpart (TACI : Fc fusion protein) or a monoclonal antibody that is specific to APRIL. Stimulation of APRIL resulted in the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-8 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 through the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB. In contrast, stimulation of APRIL had an inhibitory effect on processes that require cytoskeletal movement such as phagocytosis of opsonized zymosan and chemotaxis through an inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity. These observations demonstrate that macrophages express a membrane-bound form of APRIL which, upon stimulation, modulates the activities of macrophages through stimulation or inhibition of processes associated with inflammation.

Keywords: APRIL, inflammation, macrophage, signalling transduction, tumour necrosis factor superfamily

Introduction

APRIL (A PRoliferation-Inducing Ligand) is a type II membrane protein with a cytoplasmic region of 28 amino acids, a transmembrane domain and a 201-residue extracellular domain consisting of a stalk and a tumour necrosis factor (TNF) domain.1–3 As a member of the TNF superfamily (TNFSF), APRIL (TNFSF13) is most closely related to BAFF (the B-cell activation factor of the TNF family, TALL-1, THANK, BlyS, TNFSF13b, zTNF-4), sharing ∼ 30% sequence identity in the TNF domain.4 Both APRIL and BAFF are expressed by various cell types including myeloid cells (monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells), stromal cells within lymphoid organs and osteoclasts.5–8 Experiments using transgenic and null mice for APRIL and BAFF revealed the essential role of these molecules in B-cell survival, T-cell co-stimulation, autoimmune diseases and cancer.4,6–8 These activities of APRIL and BAFF are mediated by their interaction with appropriate receptors. BAFF and APRIL share two receptors, TACI [transmembrane activator and CAML (a calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand) interactor] and BCMA (B-cell maturation antigen), while BAFF-R (BAFF receptor, BR3) is recognized only by BAFF.6,8 These receptors are found mainly in B cells and plasma cells, but also occur in some subsets of T cells.

Using HEK293 cells expressing exogenous APRIL, it has been shown that APRIL is secreted as approximately 63 000 molecular weight non-covalent trimers through the action of furin convertase, which cleaves APRIL at its multibasic extracellular region.9 Since the cleavage reaction occurs intracellularly at the Golgi apparatus, it was thought that APRIL is not usually expressed on the cell surface. In contrast, macrophage has been known to express most members of both the TNF superfamily and their receptors on their cell surface.10–13 To investigate the role of APRIL in macrophage functions, the expression pattern of APRIL was tested in human monocytic cell lines. Unexpectedly, these cells were found to express high levels of APRIL on the cell surface. The role of APRIL was then tested in the macrophage-like cell line, THP-1, with respect to the functions associated with inflammatory processes.

Materials and methods

Monoclonal antibodies and reagents

The monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for human APRIL (clone ab16088) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); mAb for hTACI (165609) was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN); fusion protein containing an extracellular domain of hTACI and the Fc portion of human immunoglobulin G (IgG) (TACI : Fc) came from Alexis (San Diego, CA); PD08059 and U0126 originated from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA); human IgG, SB203580, and LY294002 were obtained from Calbiochem International Inc. (La Jolla, CA); and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), N-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone (TPCK), ethyl pyruvate, sulfasalazine and fibronectin were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Polyclonal antibody for βig-h3 was raised by the immunization of rabbits with recombinant βig-h3.14 The human monocytic leukaemia cell lines (THP-1, U937 and TF-1A) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD).

Small interfering RNA transfection

BAFF, APRIL, BCMA, TACI-specific small interfering (si) RNAs (pool of four siRNAs for each gene, designed by manufacturer) and control siRNA (random base sequence with no known specificity to human genes) were purchased from Dharmacon Inc. (Lafayette, CO). For transfection, THP-1 cells (5 × 103/well in six-well plates) were incubated overnight in normal growth medium (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics) before being pelleted. Transfection solution was prepared by mixing 35 μl serum-free RPMI-1640 containing 1 μm siRNA with 35 μl of serum-free RPMI-1640 containing 25-fold dilution of DharmaFECT (Dharmacon Inc.). The transfection solution was then mixed with 350 μl of growth medium without antibiotics and used to resuspend the cell pellet. The mixture containing THP-1 cells and transfection solution was then added back into six-well plates and 2 ml of growth medium/well was added for long-term culture, during which more growth medium was added as required up to 7–10 days. Down-regulation of cell surface BAFF, APRIL, TACI and BCMA was measured at 3, 5 and 10 days after transfection. The expression levels start to decrease by 3 days and complete elimination of the expression was achieved by 5–10 days.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

Five micrograms of total RNAs isolated from cells were treated with RNase-free DNase (BD-Pharmingen, San Jose, CA), and then used to generate first-strand complementary DNAs using the RevertAid™ first-strand cDNA synthesis kit with 500 ng oligo-dT (12–18 mer) primers. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers were designed with ABI PRISM Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and made by Geno Tech Corp (Daejeon, Korea). Primer sequences were 5′-AGA AGA AGC AGC ACT CTG TC-3′(forward) and 5′-CCA TGT GGA GAG AGG TTA AG-3′ (reverse) for APRIL, 5′-GGT CCA GAA GAA ACA GTC AC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGA GTT CAT CTC CTT CTT CC-3′ (reverse) for BAFF, and 5′-TGG GCT ACA CTG AGC ACC AG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGG TGT CGC TGT TGA AGT CA-3′(reverse) for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The PCR products were run on 2% agarose gel to confirm their size and purity.

Gelatin zymogram, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot analysis

The cells were activated by adding antibodies and fusion proteins to the medium containing 1 × 106/ml THP-1 cells in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 0·1% fetal bovine serum. The culture supernatants were collected 24 hr after activation and the gelatin zymogram analyses and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay were performed as described previously.15,16 Cell lysates were obtained at various time-points after activation and Western blot analysis was performed as described previously.17,18

Phagocytosis assay and flow cytometry

Zymosan opsonization and phagocytic activity were measured as previously described.11 The percentage of cells associated with zymosan was measured using flow cytometry analysis, which was performed using FACScalibur (Becton-Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). For the flow cytometric analysis of cell surface antigens, cells (5 × 105) were pelleted and incubated with 0·3 μg fluorescence-labelled primary or secondary antibodies in 30 μl FACS solution (a phosphate-buffered saline containing 0·5% bovine serum albumin and 0·01% sodium azide) for 20 min on ice. For background fluorescence, the cells were stained with an isotype-matching control antibody. The fluorescence profiles of 2 × 104 cells were collected and analysed.

Transmigration assay

Migration of cells was assessed in a 48-well microchamber (Neuroprobe, Cabin John, MD) as described previously.19 Briefly, the lower wells were filled with 27 μl RPMI-1640 (supplemented with 0·1% serum) containing chemoattractant and the upper wells were filled with 50 μl of cells at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml. The two compartments were separated by a gelatin-coated polyvinylpyrrolidone-free filter (Nucleopore, Neuro Probe Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) with 5-μm pores. After incubation for 12 hr at 37°, the number of cells that had migrated into the lower wells was counted with a haemocytometer. The experiments were performed on quadruplicate samples.

Results and discussion

Expression of APRIL was detected on the surface of human monocyte/macrophage cell lines

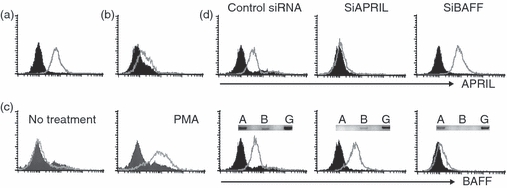

APRIL has been known to be expressed by cells of the myeloid lineage including macrophages.5–8 As most members of TNFSF are expressed on the cell surface as a membrane protein, the expression of APRIL on the cell surface of various monocytic cell lines was tested with an APRIL-specific mAb. Flow cytometry analysis detected the expression of APRIL on the surface of THP-1 cells (Fig. 1a), a human macrophage-like cell line, and U937 (Fig. 1b), a human monocytic cell line. However, the expression of APRIL was not detected in another monocytic cell line, TF-1A. Since TF-1A represents a relatively undifferentiated cell type, the cells were treated with PMA, which is known to induce macrophage differentiation.20 The expression of APRIL was induced in TF-1A cells after 2 days of PMA treatment (Fig. 1c). These data indicate that APRIL expression can be induced during macrophage differentiation and APRIL can be expressed on the surface of various cells that have macrophage-like properties. To confirm that the molecule detected by the anti-APRIL mAb in THP-1 cell was APRIL, the siRNA approach was used. THP-1 cells were separately transfected with either control siRNA or with siRNAs specific for APRIL or BAFF. Reverse transcription–PCR analysis detected a dramatic decrease in APRIL or BAFF messenger RNA in cells transfected with siRNAs specific for APRIL or BAFF, respectively (Fig. 1d). Flow cytometric analysis confirmed that cells transfected with APRIL-specific siRNA were not stained with anti-APRIL mAb whereas the expression of BAFF was unaffected (Fig. 1d). Likewise, cells transfected with BAFF-specific siRNA were stained with anti-APRIL mAb, but not with anti-BAFF mAb.

Figure 1.

Human monocytic cell lines express APRIL on the cell surface. THP-1 (a) and U937 (b) cells were stained with anti-APRIL monoclonal antibody. Histograms from specific staining (open area) and background staining (filled area, stained with mouse immunoglobulin G1) are compared. (c) TF-1A cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 10 nm of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate for 2 days and then stained for the expression of APRIL. (d) THP-1 cells were transfected with control small interfering (si) RNA or siRNAs specific for APRIL or BAFF. Transfectants were then tested for the expression of BAFF or APRIL. Each transfectant was analysed for the message level of APRIL, BAFF and GAPDH using reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (inset). A, APRIL (394 base pairs; bp); B, BAFF (370 bp); G, GAPDH (391 bp). Results are representative for three independent experiments.

The data demonstrating the expression of APRIL on the cell surface are in contrast with a previously reported observation that demonstrated the cleavage of APRIL in Golgi apparatus before its appearance on the cell membrane.9 Those observations were made on HEK293T cells, which were transfected with APRIL expression construct, so they may represent an artificial situation. APRIL expression levels were unchanged in THP-1 cells even after stimulation of THP-1 cells with lipopolysaccharide or PMA (data not shown). Furthermore, APRIL expression levels increased in TF-1A cells after PMA treatment. This indicates that APRIL, in at least certain macrophage-like cell lines, remain to be expressed on the cell surface even after activation.

Stimulation of cell surface APRIL induces the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators through activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB

Members of the TNFSF are normally expressed on the cell surface of macrophages.10,15,21–23 These membrane-bound ligands tend to induce an activation signal when they interact with their cognate counterparts. The signalling through members of the ligand part of the TNFSF has been reported in TRANCE (TNFSF11),24 CD30L (TNFSF8),25 FasL (TNFSF6),26 TRAIL (TNFSF10)27 and BAFF.11 The observation showing the expression of APRIL on the surface of macrophage-like cells and the up-regulation of its expression levels by PMA-mediated macrophage differentiation raise the possibility that stimulation of APRIL may also generate signalling and regulate macrophage activities.

To analyse the role of APRIL in the function of macrophages, THP-1 cells were stimulated with a recombinant protein containing an extracellular portion of TACI fused to an Fc portion of human IgG. Stimulation of THP-1 cells with TACI : Fc fusion protein, but not with human IgG, resulted in the induction of pro-inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-8 (IL-8) and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9; Fig. 2a,b). Since TACI can interact with both APRIL and BAFF, THP-1 cells were then stimulated with APRIL-specific mAbs. As shown in Fig. 2(a,b), anti-APRIL mAb induced the expression of IL-8 and MMP-9. To demonstrate that these responses are the result of the specific interaction between APRIL and anti-APRIL mAb, siRNA-transfected cell were tested. As shown in Fig. 2(c), cells transfected with siAPRIL responded to anti-BAFF mAb but treatment with anti-APRIL mAb failed to induce the production of IL-8 (Fig. 2c) and MMP-9 (Fig. 2d). In contrast, siBAFF-transfected cells responded to only anti-APRIL mAb. These data indicate that a specific stimulation of APRIL can induce an activation signal in THP-1 cells.

Figure 2.

The stimulation of APRIL induced the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) in THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were stimulated with 1, 3, or 10 μg/ml concentrations of TACI : Fc or anti-APRIL monoclonal antibody (mAb) for 24 hr and the culture supernatant was collected. Gelatin zymogram was performed to analyse the expression of MMP-9 (a) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed to measure the concentrations of IL-8 (b). (c) No treatment control; L, lipopolysaccharide at 1 μg/ml; H, human immunoglobulin G (IgG; 10 μg/ml), M, mouse IgG (10 μg/ml). (c, d) THP-1 cells transfected with small interfering RNA were stimulated with 1 μg/ml of anti-BAFF mAb (b), anti-APRIL mAb (a), or isotype-matching mouse IgG (M) for 24 hr. Culture supernatants were then collected for the measurement of MMP-9 and IL-8. Results are representative for three independent experiments.

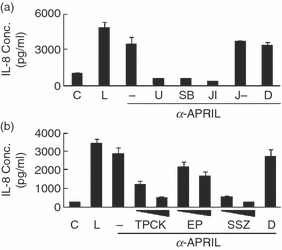

The expression of cytokines and MMP-9 in macrophages requires the activation of various signalling molecules such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). In the case of BAFF-mediated activation, the involvement of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) MAPK and NF-κB, but not p38 and Jun N-terminal kniase (JNK) MAPK, has been demonstrated.11 To identify the MAPKs that mediate APRIL-induced signalling events, THP-1 cells were stimulated with an anti-APRIL mAb in the presence of U0126, SB203580 and JNK-I for the specific inhibition of ERK, p38 and JNK, respectively. APRIL-mediated induction of IL-8 (Fig. 3a) and MMP-9 (data not shown) was blocked by all these inhibitors. This is in sharp contrast to BAFF-mediated signalling, which was inhibited by inhibitors for ERK but not with specific inhibitors for p38 and JNK.

Figure 3.

The APRIL-induced expression of interleukin-8 (IL-8) requires the activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). (a) THP-1 cells were pre-treated with 10 μm of U0126 (U), SB203580 (SB), Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor (JI), or negative control of JNK inhibitor (J–) for 30 min and the cells were stimulated with anti-APRIL monoclonal antibody (mAb; 1 μg/ml). Culture supernatants were collected after 24 hr to measure IL-8 concentrations using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. C, no treatment control; L, 1 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide as a positive control; D, 0·1% dimethyl sulphoxide as a vehicle control. D, THP-1 cells were pre-treated for 30 min with 20 and 40 μm TPCK, 5 and 10 mm ethyl pyruvate (EP), or 0·5 and 1 mm of sulfasalzine (SSZ) and stimulated with anti-APRIL mAb (1 μg/ml). Culture supernatants were collected after 24 hr to measure IL-8 concentrations. Results are representative for three independent experiments.

Nuclear factor-κB is the major transcription factor that is induced during inflammatory activation of many cell types. To test the involvement of NF-κB in the APRIL-mediated signalling pathway, cellular stimulation was performed in the presence of NF-κB-specific inhibitors such as TPCK,28 ethyl pyruvate29 and sulfasalazine.30 APRIL-induced expression of IL-8 (Fig. 3b) and MMP-9 (data not shown) was dose-dependently inhibited by these inhibitors. These results indicate that the signalling pathway induced by APRIL is mediated by all three MAPKs and NF-κB.

Both TACI and BCMA, as receptors for BAFF and APRIL, are known to induce survival signals in B cells.4 THP-1 cells express both BCMA and TACI (Fig. 4a). To demonstrate that APRIL-mediated activation of THP-1 does not require the action of these receptors, THP-1 cells lacking both TACI and BCMA were generated using specific siRNAs. Co-transfection of THP-1 cells with TACI- and BCMA-specific siRNAs completely eliminated the expression of both TACI and BCMA but the expression levels of APRIL were not affected (Fig. 4a). When these cells were stimulated with anti-APRIL mAb, the expression of both MMP-9 and IL-8 was induced at levels comparable to those induced by lipopolysaccharide. Treatment with TACI : Fc also induced MMP-9 and IL-8 expression and these responses were blocked by treatment with anti-TACI mAb, indicating that that the interaction was specific (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

APRIL-induced expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) and interleukin-8 (IL-8) is independent of the expression TACI or BCMA in THP-1 cells. (a) THP-1 cells were either transfected with control small interfering (si) RNA or siRNAs specific for BCMA and TACI. Cell surface expression levels of APRIL, TACI and BCMA were measured after 5 days. Histograms from specific staining (open area) and background staining (filled area, stained with mouse immunoglobulin G1; IgG1) were compared. (b) Cells transfected with TACI and BCMA specific siRNAs were stimulated with 1 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide, anti-APRIL monoclonal antibody (mAb), mouse IgG, TACI : Fc, or TACI : Fc plus 1 μg/ml of anti-TACI mAb for 24 hr and the culture supernatant was collected for the analysis of MMP-9 activity and IL-8 measurement. Transfection experiments were independently repeated twice with essentially the same results. ***P < 0·001 when compared with the control.

Stimulation of APRIL leads to the inhibition of cytoskeletal movement associated with phagocytosis and chemotaxis through inhibition of phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase activity

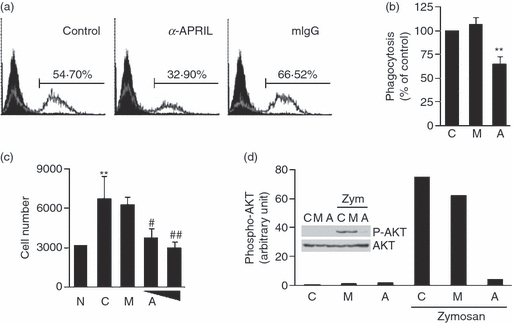

During inflammatory processes, macrophages perform various activities along with the production of pro-inflammatory mediators. These include phagocytosis of foreign molecules and migration toward chemoattractive substances. BAFF-mediated signalling suppressed processes associated with cytoskeletal movement such as phagocytic activity and transmigration.21 To determine whether APRIL-mediated signalling has similar effects, THP-1 cells were stimulated with anti-APRIL mAb and then incubated with fluorescence-labelled opsonized-zymosan. Interestingly, treatment of the cells with anti-APRIL mAb suppressed phagocytosis of opsonized zymosan by 61 ± 3·5% with statistical significance (Fig. 5a,b). Immunofluorescence analysis of fluorescence-labelled zymosan further indicated that zymosan particles tended to stay adhered to cells without being internalized (data not shown). As phagocytosis requires cytoskeletal movements, it is possible that APRIL-mediated signalling somehow affects cytoskeletal movement associated with phagocytosis. To confirm this possibility, migration assay was performed in cells stimulated with anti-APRIL mAb. As shown in Fig. 5(c), treatment with the anti-APRIL mAb dose-dependently blocked the migration of THP-1 cells toward fibronectin. Fibronectin was used as a chemoattractant because it is produced during tissue injury and has chemotactic activity for leucocytes.31–34

Figure 5.

The stimulation of APRIL inhibited phagocytosis of opsonized zymosan and transmigration in THP-1 cells through suppressing the activities of phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase (PI3K). (a) THP-1 cells were pre-treated for 30 min with 10 μg/ml of anti-APRIL monoclonal antibody (mAb) or mouse immunoglobulin G (mIgG). Cells were then incubated with 30 μg/ml of fluorescence-labelled opsonized zymosan. Three hours later, fluorescence levels in each sample were measured using flow cytometry. (b) The assay in (a) was repeated three times and the flow cytometry results were subjected to a statistical analysis after setting the control measurement as 100%. Values indicate mean + SEM. **P < 0·01, when compared with the control. C, no treatment control; M, mIgG; A, anti-APRIL. (c) Transmigration potential of THP-1 cells pre-treated with 20 μg/ml of mIgG (M) or 10 and 20 μg/ml of anti-APRIL mAb (A) was measured with 10 μg/ml of fibronectin as a chemoattractant. Experiments were repeated three times for statistical analysis. Numbers represent mean + SEM of migrated cell numbers. **P < 0·01, when compared with the no treatment control (N). #P < 0·05, ##P < 0·01, when compared with the control (C). (d) THP-1 cells were stimulated with 30 μg/ml of opsonized zymosan in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml of anti-APRIL mAb (A) or mouse IgG (M) for 3 hr. Cell lysates were obtained after 2 hr for the Western blot analysis of AKT and phospho-AKT (inset). Phospho-AKT band intensities were then measured with densitometer and normalized with band intensities of corresponding AKT. Results are representative for three independent experiments.

Zymosan that has been opsonized by immunoglobulins stimulates FcR and its downstream mediators on the surface of macrophages. To find out the signalling adapter that was affected by APRIL, the activation status of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) was tested. PI3K/AKT has been known to be required for the pseudopod extension and closure of the phagosome35. Phosphorylation of AKT, which was induced by the treatment with opsonized zymosan, was blocked by the presence of anti-APRIL mAb, but not with mouse IgG (Fig. 5d). Furthermore, the treatment of 3 or 30 μm of LY294002 as a specific inhibitor of PI3K resulted in the inhibition of phagocytosis by 11·6 and 20·4%, respectively. This confirms the essential role of the PI3K/AKT pathway in the phagocytosis of opsonized zymosan. These results indicate that the APRIL-mediated inhibition of PI3K activity is responsible, at least partially, for the inhibition of phagocytosis.

These data indicate that the stimulation of APRIL with its counterparts (either soluble or cell membrane-bound form) can regulate the inflammatory activities of macrophages. Stimulation of APRIL-expressing macrophages through cell-to-cell interaction with the receptor-expressing cells may stimulate the inflammatory activation of these cells as well as modulation of their phagocytic activity. In reverse, either membrane-bound or soluble forms of APRIL can activate the macrophage activation through conventional receptor-mediated signalling pathways. Induction of two-way activation pathways (one through APRIL and the other through its counterparts) via interaction between APRIL and its counterparts is expected to contribute to the inflammatory responses associated with normal immune responses or pathological conditions. Various cytokines and pro-inflammatory mediators are known to be associated with chronic inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis. APRIL and its counterparts, in addition to those agents, is expected to enhance the inflammatory responses in macrophages and contribute to the pathogenesis of those diseases. To identify the importance of this signalling in the modulation of immune responses, further research is required in animal models and clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Korean Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (The Regional Core Research Program ‘Anti-aging and Well-being Research Center’ School of Medicine, Kyungpook National University).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- APRIL

a proliferation-inducing ligand

- BAFF

B-cell activation factor of the TNF family

- BAFF-R

BAFF receptor

- BCMA

B-cell maturation antigen

- CD30L

CD30 ligand

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- IL-8

interleukin-8

- JNK

Jun N-terminal kinase

- JNK-I1

JNK inhibitor I

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- OA

osteoarthritis

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PMA

12-phorbol 13-myristate acetate

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TACI

transmembrane activator and CAML [a calcium-modulating cyclophilin ligand] interactor

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- TNFSF

TNF superfamily

- TPCK

N-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone

- TRAIL

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- TRANCE

TNF-related activation-induced cytokine

References

- 1.Hahne M, Kataoka T, Schroter M, et al. APRIL, a new ligand of the tumor necrosis factor family, stimulates tumor cell growth. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1185–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly K, Manos E, Jensen G, Nadauld L, Jones DA. APRIL/TRDL-1, a tumor necrosis factor-like ligand, stimulates cell death. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1021–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shu HB, Hu WH, Johnson H. TALL-1 is a novel member of the TNF family that is down-regulated by mitogens. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;65:680–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackay F, Schneider P, Rennert P, Browning J. BAFF AND APRIL: a tutorial on B cell survival. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:231–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorelik L, Gilbride K, Dobles M, Kalled SL, Zandman D, Scott ML. Normal B cell homeostasis requires B cell activation factor production by radiation-resistant cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:937–45. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng LG, Mackay CR, Mackay F. The BAFF/APRIL system: life beyond B lymphocytes. Mol Immunol. 2005;42:763–72. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dillon SR, Gross JA, Ansell SM, Novak AJ. An APRIL to remember: novel TNF ligands as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:235–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider P. The role of APRIL and BAFF in lymphocyte activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:282–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Fraga M, Fernandez R, Albar JP, Hahne M. Biologically active APRIL is secreted following intracellular processing in the Golgi apparatus by furin convertase. EMBO reports. 2001;2:945–51. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim WJ, Kang YJ, Suk K, Park JE, Kwon BS, Lee WH. Comparative analysis of the expression patterns of various TNFSF/TNFRSF in atherosclerotic plaques. Immunol Invest. 2008;37:359–73. doi: 10.1080/08820130802123139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeon ST, Kim WJ, Lee SM, et al. Reverse signaling through BAFF differentially regulates the expression of inflammatory mediators and cytoskeletal movements in THP-1 cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:148–56. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SH, Kang YJ, Kim WJ, et al. TWEAK can induce pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinase-9 in macrophages. Circ J. 2004;68:396–9. doi: 10.1253/circj.68.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mach F, Schonbeck U, Sukhova GK, Bourcier T, Bonnefoy JY, Pober JS, Libby P. Functional CD40 ligand is expressed on human vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages: implications for CD40–CD40 ligand signaling in atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HJ, Kim IS. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced gene product, as a novel ligand of integrin alpha(M)beta(2), promotes monocytes adhesion, migration and chemotaxis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:991–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee WH, Kim SH, Lee Y, Lee BB, Kwon B, Song H, Kwon BS, Park JE. Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 14 is involved in atherogenesis by inducing proinflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:2004–10. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.098945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim WJ, Lee WH. LIGHT is expressed in foam cells and involved in destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques through induction of matrix metalloproteinase-9 and IL-8. Immune network. 2004;4:116–22. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae E, Kim WJ, Kang YM, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced tumour necrosis factor receptor-related protein-mediated macrophage stimulation may induce cellular adhesion and cytokine expression in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:410–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim WJ, Bae EM, Kang YJ, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced TNFR family-related protein (GITR) mediates inflammatory activation of macrophages that can destabilize atherosclerotic plaques. Immunology. 2006;119:421–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chun KR, Bae EM, Kim JK, Suk K, Lee WH. Suppression of the lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of MARCKS-related protein (MRP) affects transmigration in activated RAW264.7 cells. Cell Immunol. 2009;2:92–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu X, Moscinski LC, Valkov NI, Fisher AB, Hill BJ, Zuckerman KS. Prolonged activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is required for macrophage-like differentiation of a human myeloid leukemic cell line. Cell Growth Differ. 2000;11:191–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeon ST, Kim WJ, Lee SM, et al. Reverse signaling through BAFF differentially regulates the expression of inflammatory mediators and cytoskeletal movements in THP-1 cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:148–56. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SH, Lee WH, Kwon BS, Oh GT, Choi YH, Park JE. Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 12 may destabilize atherosclerotic plaques by inducing matrix metalloproteinases. Jpn Circ J. 2001;65:136–8. doi: 10.1253/jcj.65.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armitage RJ. Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily members and their ligands. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:407–13. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen NJ, Huang MW, Hsieh SL. Enhanced secretion of IFN-gamma by activated Th1 cells occurs via reverse signaling through TNF-related activation-induced cytokine. J Immunol. 2001;166:270–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerutti A, Schaffer A, Goodwin RG, Shah S, Zan H, Ely S, Casali P. Engagement of CD153 (CD30 ligand) by CD30+ T cells inhibits class switch DNA recombination and antibody production in human IgD+ IgM+ B cells. J Immunol. 2000;165:786–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki I, Fink PJ. The dual functions of fas ligand in the regulation of peripheral CD8+ and CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1707–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chou AH, Tsai HF, Lin LL, Hsieh SL, Hsu PI, Hsu PN. Enhanced proliferation and increased IFN-gamma production in T cells by signal transduced through TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J Immunol. 2001;167:1347–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ballif BA, Shimamura A, Pae E, Blenis J. Disruption of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) signaling by the anti-tumorigenic and anti-proliferative agent n-alpha-tosyl-l-phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12466–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009939200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Y, Englert JA, Yang R, Delude RL, Fink MP. Ethyl pyruvate inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB-dependent signaling by directly targeting p65. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:1097–105. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.079707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahl C, Liptay S, Adler G, Schmid RM. Sulfasalazine: a potent and specific inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1163–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Birdsall HH, Porter WJ, Green DM, Rubio J, Trial J, Rossen RD. Impact of fibronectin fragments on the transendothelial migration of HIV-infected leukocytes and the development of subendothelial foci of infectious leukocytes. J Immunol. 2004;173:2746–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark RA, Wikner NE, Doherty DE, Norris DA. Cryptic chemotactic activity of fibronectin for human monocytes resides in the 120-kDa fibroblastic cell-binding fragment. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:12115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulai JI, Chen H, Im HJ, Kumar S, Hanning C, Hegde PS, Loeser RF. NF-kappa B mediates the stimulation of cytokine and chemokine expression by human articular chondrocytes in response to fibronectin fragments. J Immunol. 2005;174:5781–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thibault MM, Hoemann CD, Buschmann MD. Fibronectin, vitronectin, and collagen I induce chemotaxis and haptotaxis of human and rabbit mesenchymal stem cells in a standardized transmembrane assay. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:489–502. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.May RC, Machesky LM. Phagocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1061–77. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]