Abstract

One of the main secondary toxic side effects of anti-mitotic agents used to treat cancer patients is intestinal mucositis. Previous data showed that cathepsin D activity, contributing to the proteolytic lysosomal pathway, is up-regulated during intestinal mucositis in rats. At the same time, cathepsin inhibition limits intestinal damage in animal models of inflammatory bowel diseases. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of cathepsin inhibition on methotrexate-induced mucositis in rats. Male Sprague–Dawley rats received saline solution subcutaneously as the control group or 2·5 mg/kg of methotrexate for 3 days (D0–D2). From D0 to D3 methotrexate-treated rats also received intraperitoneal injections of pepstatin A, a specific inhibitor of cathepsin D or E64, an inhibitor of cathepsins B, H and L, or vehicle. Rats were euthanized at D4 and jejunal samples were collected. Body weight and food intake were partially preserved in rats receiving E64 compared with rats receiving vehicle or pepstatin A. Cathepsin D activity, used as a marker of lysosomal pathway, was reduced both in E64 and pepstatin-treated rats. However, villus atrophy and intestinal damage observed in methotrexate-treated rats were restored in rats receiving E64 but not in rats receiving pepstatin A. The intramucosal concentration of proinflammatory cytokines, interleukin-1β and cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC)-2, was markedly increased in methotrexate-treated rats receiving vehicle or pepstatin A but not after E64 treatment. In conclusion, a large broad inhibition of cathepsins could represent a new potential target to limit the severity of chemotherapy-induced mucositis as opposed to the inhibition of cathepsin D alone.

Keywords: chemotherapy, E64, intestine, lysosome, mucositis

Introduction

Chemotherapy is often associated with side effects such as mucositis because of the anti-mitotic properties of drugs. Because their actions are not specific to tumour tissues, they also induce deleterious effects on rapidly proliferating cells such as bone marrow and gut mucosa cells [1]. Haematopoietic, oral and gastrointestinal toxicities are the most frequently observed, and may lead to a reduction in the dose or even a cessation of chemotherapeutic treatments. Intestinal mucositis remains a major concern during cancer chemotherapy in more than 40% of cancer patients after standard doses of treatment, and in almost 100% of patients treated with high doses [2]. There is no efficient standard treatment to reduce oral and gastrointestinal injuries, even though nutritional strategies have been developed recently. The main clinical symptoms of intestinal mucositis, including nausea, bloating, abdominal pain and diarrhoea, generally peak on day 3 after chemotherapy initiation [2].

In the gut, mucosal damage and barrier function alterations have been described as the consequences of different processes: apoptosis, hypoproliferation [3], inflammatory response [4], altered absorptive capacity [5] and bacteria proliferation and colonization [6,7]. However, we have reported recently that alterations of gut protein metabolism could also be involved in the occurrence of mucosal damage during chemotherapy-induced intestinal mucositis in rats [8,9]. In inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) the lysosomal protease, cathepsin D, is up-regulated in intestinal macrophages from the lamina propria [10] and cathepsin inhibition was associated with less intestinal damage in an IBD-like animal model [11]. As we have shown recently that cathepsin D mRNA and activity were increased during chemotherapy-induced mucositis in rats [8,9], we hypothesized that lysosomal proteolytic pathways could be involved in the occurrence of mucositis.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of cathepsin inhibition on mucosal damage and inflammatory response during methotrexate-induced intestinal mucositis in rats.

Materials and methods

Animals

Animal care and experimentation complied with both French regulations and European Community regulations (Official Journal of the European Community L 358, 18/12/1986) and M.C. is authorized by the French government to use animal models (authorization no. 76–107). During 1 week, 200–250 g male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 20; Elevage Janvier, Le Gesnet St-Isle, France) were acclimatized at 25°C with a 12-h light–dark cycle. Animals were housed individually in metabolic cages for 4 days before the study. Rats were given free access to water and standard chow during the study.

Mucositis induction and cathepsin inhibition

As described previously [8,9], rats were injected subcutaneously during the first 3 days (D0, D1 and D2) with 2·5 mg/kg MTX (Teva Pharma, Courbevoie, France) or saline solution as control. From D0 to D3, rats also received intraperitoneal injections of pepstatin A (10 mg/kg; Bachem, Weil am Rhein, Germany), E64 (5 mg/kg; Sigma Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) or vehicle, as described previously [11]. Pepstatin A and E64 are inhibitors of cathepsin D and cathepsins B, H and L, respectively. Body weight and food intake were monitored at 24-h intervals. All rats were euthanized at D4, which correspond to the acute phase of intestinal mucositis in this model [8,9]. Thus, we studied four groups of five rats comprising a control group, the methotrexate group receiving vehicle, the methotrexate group receiving pepstatin A and the methotrexate group receiving E64.

Animals were decapitated after carbon dioxide inhalation. Then, the jejunum was taken and rinsed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1·5 mM KH2PO4). For histological assessment, proximal samples of jejunum were fixed in formalin (10%). Consecutive pieces (each 1 cm long) were removed, respectively, and mucosa was scraped for the determination of mRNA expression, analysis of cytokine concentrations and determination of proteolytic activities. Samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. For mRNA, Trizol® Reagent (Invitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France) was added previously to collecting tubes.

Histological parameters

For histological and immunohistochemistry assessments, jejunal samples were fixed in formalin 10% and treated as described previously [8,9]. Briefly, sections were scored by the same pathologist (M.A.) blinded to the treatment allocation. Epithelial necrosis, inflammatory cell infiltration and exocytosis were assessed using semiquantitative scores, ranging from 0 (no damage) to 3 (severe damages) for each parameter: villus atrophy, necrosis, inflammation and exocytosis. Villus height was measured on 10 well-orientated villi from each rodent using Leica QWin analysis software (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany).

Intestinal cytokine concentrations and mRNA levels

Fifty µl of protein extracts of colonic mucosa were assessed in duplicate for determination of concentrations of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC)-2, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-4, IL-10 and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α using a Fluorokine MAP kit (R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK). This assay relies on the use of polystyrene beads, each with a unique signature mix of fluorescent dyes that can be discriminated by a laser-based detection instrument (Bioplex 2200; BioRad Laboratories, Marnes la Coquette, France). Each bead type was coated with a specific antibody to the cytokine of interest. Results were expressed as pg/mg proteins.

After reverse transcription of 1·5 µg total RNA into cDNA by using 200 units of SuperScript™ II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was performed by SYBR™ Green technology on a BioRad CFX96 real-time PCR system (BioRad Laboratories) in duplicate for each sample. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as the endogenous reference gene. Primers are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer pairs for real-time polymerase chain reaction.

| Target gene | Primer sequences | Product size (base pairs) |

|---|---|---|

| Rat CINC-2 | Forward: 5′-GCACCCAAACCGAAGTCA-3′ | 171 |

| Reverse: 5′-AGAAGCCAGCGTTCACCA-3′ | ||

| Rat IL-1β | Forward: 5′-GGGATGATGACGACCTGC-3′ | 153 |

| Reverse: 5′-ATACCACTTGTTGGCTTATGTT-3′ | ||

| Rat TNF-α | Forward: 5′-GTCGTAGCAAACCACCAAGC-3′ | 214 |

| Reverse: 5′-GGTATGAAGTGGCAAATCGG-3′ | ||

| Rat GAPDH | Forward: 5′-CATCACTGCCACTCAGAAGA-3′ | 316 |

| Reverse: 5′-AAGTCACAGGAGACAACCG-3′ |

CINC, cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Cathepsin D activity and expression

Lysosomal cathepsin D activity was quantified using the InnoZyme™ Cathepsin D Immunocapture Activity Assay Kit Fluorogenic (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA, USA), as described previously [12].

Cathepsin D expression was assessed by immunoblot. Briefly, 25 µg of proteins were added to lauryl dodecyl sulphate sample buffer and boiled for 10 min. After separation in 4–12% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Invitrogen), samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose (GE Healthcare, Orsay, France) by voltage gradient transfer. Membranes were blocked in 5% skimmed milk for 1·5 h followed by several washes [Tris-buffered saline-Tween (TBS-T)]. Membranes were then incubated overnight in TBS-T and 5% skimmed milk with goat polyclonal antibody anti-cathepsin D (1:500; SantaCruz, Tebu-Bio, Le Perray en Yvelines, France) and mouse anti-β-actin (1:1000; Sigma Aldrich). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (SantaCruz, Tebu-bio) were used as secondary antibodies (1:1000). Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) and autoradiography (ECL and Hyperfilm ECL; GE Healthcare). Protein bands were quantified by densitometry using ImageScanner III and ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare).

Proteasome activities

Proteasome activities were evaluated on jejunal mucosa, as described previously [13], with spectrofluorimetry on a microtitre plate fluorometer (Mithras LB 940; Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) using fluorogenic proteasome substrate, succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-4-methylcoumaryl-7-amide (Suc-LLVY-MCA) (PSIII; Calbiochem) for chymotrypsin-like activity, butoxycarbonyl-Leu-Ser-Thr-Arg-MCA (Boc-LSTR-MCA) (Sigma Aldrich) for trypsin-like activity and carbobenzoxy-Leu-Leu-Glu-MCA (Z-LLE-MCA) (Sigma Aldrich) for caspase-like or peptidyl-glutamyl peptide-hydrolyzing (PGPH) activity, in the presence or absence of proteasome inhibitor, 40 µM MG132 (Sigma Aldrich). Thus proteasome activity was calculated by the difference between the activity measured in the absence of Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-CHO (MG132) and the activity measured in the presence of MG132.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5·01 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using, as appropriate, either a one-way analysis of variance (anova) with Tukey's post-hoc tests or a Kruskall–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple post-hoc tests. For daily monitored parameters, a repeated-measures anova was performed. P < 0·05 was considered significant.

Results

Food intake and body weight

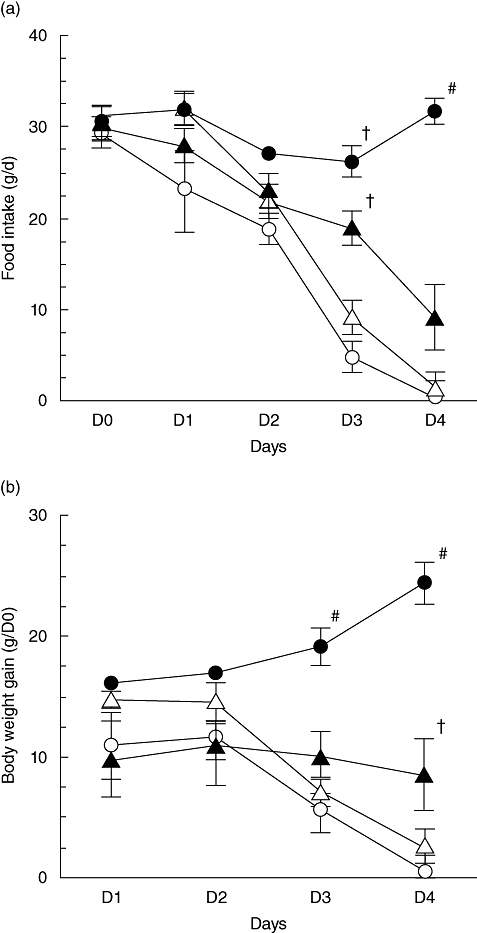

From day 3, food intake decreased in MTX-treated rats compared with control rats (P < 0·05, Fig. 1a). Treatment with E64 delayed the decrease of food intake, which was reduced only at D4 (P < 0·05). In contrast, injections of pepstatin A had no effect.

Fig. 1.

Food intake (a) and body weight changes (b) in control (closed circles) and methotrexate (MTX)-treated rats receiving vehicle (open circles), pepstatin A (open triangles) or E64 (closed triangles). Values are means ± standard error of the mean from five rats in each group. #P < 0·05 versus all other groups, †P < 0·05 versus MTX-treated rats receiving vehicle or pepstatin A.

Body weight increased over time in control rats, whereas it decreased in MTX-treated rats receiving the vehicle (P < 0·05, Fig. 1b). In rats receiving E64, body weight remained unchanged. By contrast, it decreased in pepstatin A-treated rats to the same extent as in MTX-treated receiving the vehicle.

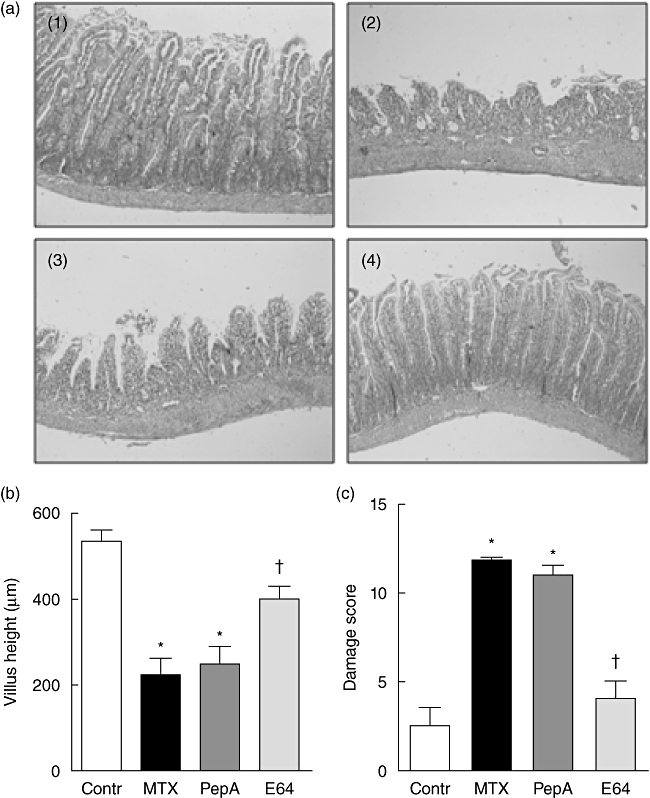

Severity of intestinal mucositis

In MTX-treated rats receiving pepstatin A or vehicle, villus height decreased compared with control rats (P < 0·05, Fig. 2a and b). In rats receiving E64, villus height was partially restored. Similarly, jejunal damage score was increased markedly in MTX-treated rats receiving either pepstatin A or vehicle (P < 0·05) but not in rats receiving E64 (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

Histology, villus height and damage score in the jejunum. Representative observations (×5) (a), villus height (b) and damage score (c) in jejunal mucosa of control [(1) or open bars] and methotrexate (MTX)-treated rats receiving vehicle [(2) or closed bars], pepstatin A [(3) or dark grey bars] or E64 [(4) or grey bars]. Values are means ± standard error of the mean from five rats in each group. *P < 0·05 versus control rats, †P < 0·05 versus MTX-treated rats receiving vehicle or pepstatin A.

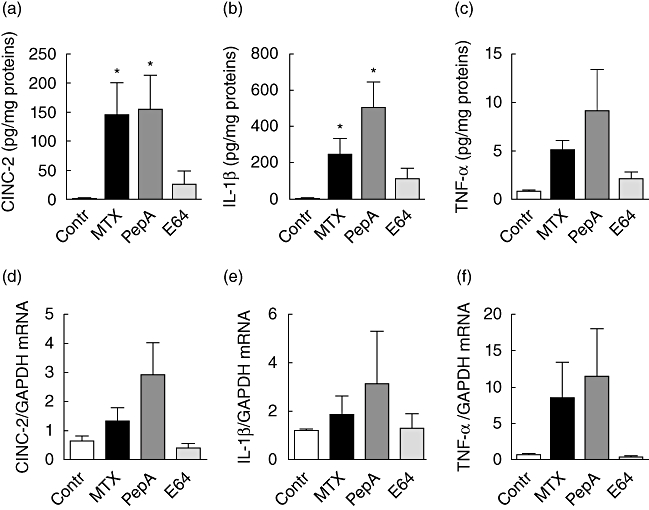

Jejunal inflammatory response

Compared to control animals, the concentration of intramucosal proinflammatory cytokines was increased in MTX-treated rats receiving vehicle or pepstatin A but not in rats receiving E64. Indeed, CINC-2 concentration increased markedly both in MTX-treated rats and in pepstatin A-treated rats (both approximately 200-fold, P < 0·05, Fig. 3a). In rats receiving E64, CINC-2 concentration was partially restored to control level. The increase averaged 36-fold but did not reach significance (Fig. 3a). The concentration of IL-1β increased approximately 100- and 200-fold in MTX-treated and pepstatin A-treated rats, respectively (both P < 0·05, Fig. 3b). In rats receiving E64, IL-1β concentration was partially restored as IL-1β increase was approximately 46-fold. Consequently, IL-1β did not differ significantly between control and E64-treated rats. A similar pattern was observed for TNF-α with approximately six, 11- and threefold increase in MTX, pepstatin A and E64-treated rats, respectively (Fig. 3c). However, differences did not reach significance. Similar patterns were observed for CINC-2, IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA levels (Fig. 3d–f).

Fig. 3.

Intramucosal concentrations and mRNA levels of cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant (CINC)-2 (a,d), interleukin-1β (b,e) and tumour necrosis factor-α (c,f) in the jejunum of control (open bars) and methotrexate (MTX)-treated rats receiving vehicle (closed bars), pepstatin A (dark grey bars) or E64 (grey bars). Values are means ± standard error of the mean from five rats in each group. *P < 0·05 versus control rats, †P < 0·05 versus MTX-treated rats receiving vehicle or pepstatin A.

In several samples, the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-4 and IL-10 remained undetectable.

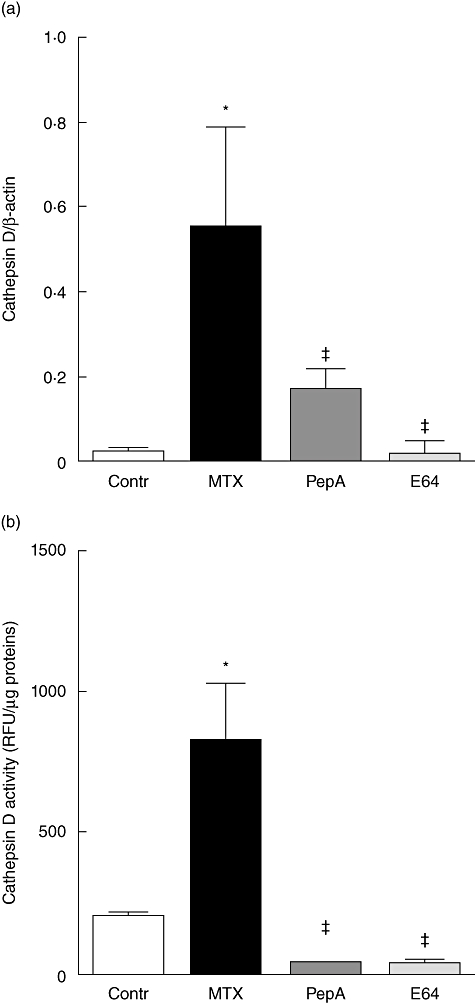

Cathepsin D expression and activity

Cathepsin D expression was increased markedly in MTX-treated rats compared with controls (P < 0·05, Fig. 4a). In rats receiving pepstatin A or E64, cathepsin D expression was restored. A similar pattern was observed for cathepsin D activity (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Cathepsin D expression (a) and activity (b) in the jejunum of control (open bars) and methotrexate (MTX)-treated rats receiving vehicle (closed bars), pepstatin A (dark grey bars) or E64 (grey bars). Values are means ± standard error of the mean from five rats in each group. *P < 0·05 versus control rats, ‡P < 0·05 versus MTX-treated rats.

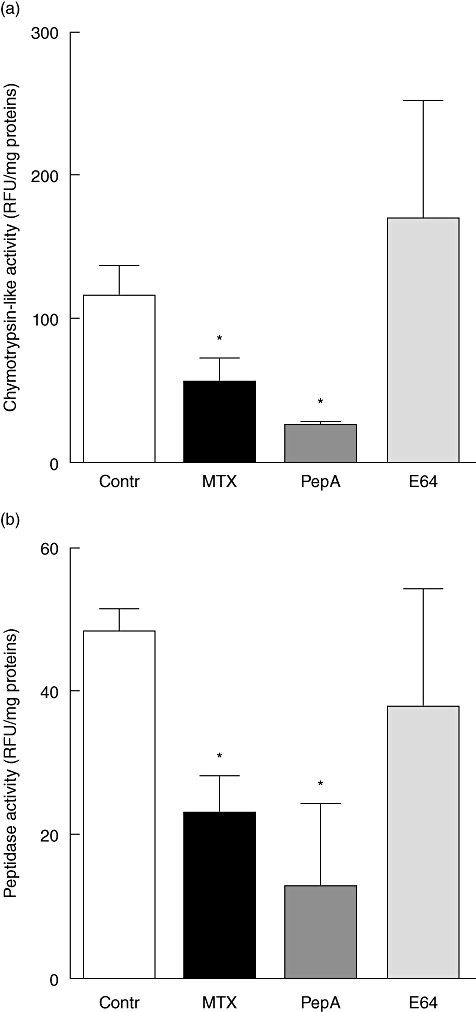

Proteasome activities

Chymotrypsin-like and peptidase proteasome activities were decreased in MTX-treated and pepstatin A-treated rats compared with controls (both P < 0·05, Fig. 5a and b). In rats receiving E64, chymotrypsin-like and peptidase activities were restored to control levels (Fig. 5a and b). Caspase-like and trypsin-like activities were not affected significantly by treatment (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Chymtrypsin-like (a) and peptidase (b) activities of proteasome in the jejunum of control (open bars) and methotrexate (MTX)-treated rats receiving vehicle (closed bars), pepstatin A (dark grey bars) or E64 (grey bars). Values are means ± standard error of the mean from five rats in each group. *P < 0·05 versus control rats.

Discussion

Intestinal mucositis is a common side effect of chemotherapy and may cause treatment reduction or withdrawal. Different processes lead to intestinal mucositis: apoptosis, hypoproliferation [3], inflammatory response [4], altered absorptive capacity [5], enhanced intestinal permeability [9] and bacteria proliferation and colonization [6,7]. Recently, we also showed that alterations of gut protein metabolism may contribute to the occurrence of intestinal mucositis [8,9].

In the present study, we showed that the proteolytic lysosomal pathway is involved in the severity of intestinal mucositis and that cathepsin inhibition could be a potential therapeutic strategy to limit mucositis.

Recently, it has been suggested that proteolysis could be involved in the regulation of several cellular pathways and in particular of the inflammatory response [11,14]. Among the different proteolytic pathways, the lysosomal pathway appears to be of interest during mucositis, as cathepsin D activity was correlated with jejunal villus atropy [9]. During IBD, cathepsin D expression is increased in macrophages of the lamina propria [10] and cathepsin inhibition decreased intestinal damage [11]. In contrast, the ubiquitin–proteasome system was down-regulated during mucositis [9], whereas it is involved in the pathophysiology of IBD [12,14–16] or irritable bowel syndrome [17].

The proteases cathepsin B, H and L are members of the cysteine protease family and cathepsin D is an aspartate protease. The proteolytic activity of these cathepsins plays an important role in the generation of antigenic peptides from larger polypeptides presented on class II molecules to T cells [18]. Several classes of proteases, including cathepsins B, L and D, are thought to be involved in lysosomal turnover of proteins. Cathepsin D has the potential to initiate a proteolytic cascade and to degrade and remodel extracellular matrix [19]. Cathepsin D-deficient mice are born normally, but die at postnatal day 26 because of massive intestinal necrosis, thromboembolism and lymphopenia [20]. We have shown previously that cathepsin D mRNA, protein expression and activity are increased during chemotherapy-induced mucositis in rats [8,9]. In the present study, we demonstrate that cathepsin inhibition limits intestinal damage and inflammatory response, suggesting the involvement of the lysosomal proteolytic pathway in the occurrence of mucositis. However, pepstatin A, a specific inhibitor of cathepsin D, did not induce preventive effects on methotrexate treatment. It is known that pepstatin A does not penetrate cell membrane easily and some complexes such as penetratin–pepstatin A have been evaluated [21]. Unlike other proteases, cathepsin D is not secreted and is not found extracellularly in physiological conditions, but cathepsin D can escape the normal targeting mechanism and can be secreted from the cells into extracellular matrix in pathological conditions [22]. In the present study, pepstatin A induced down-regulation of cathepsin D activity without limiting the effects of chemotherapy, suggesting that the inhibition of cathepsin D is not sufficient to have beneficial effects during chemotherapy. In contrast, E64, an inhibitor of cathepsins B, H and L, prevented methotrexate-induced intestinal damage. These beneficial effects may be explained by the larger pattern of action of E64 compared with pepstatin A. Interestingly, E64 also inhibited cathepsin D activity in our model, probably by the negative feedback of other proteases. However, these data were obtained from a small sample size and thus should be confirmed in a larger study.

Our results suggest that cathepsin inhibition may be a potential therapeutic strategy to limit the intestinal side effects of chemotherapy. However, in the present study we did not use a tumour-bearing model and thus we were not able to determine whether cathepsin inhibition can alter the sensitivity of tumour cells to chemotherapy. This latter point should be evaluated in further studies.

Proteasome activities, e.g. chymotrypsin-like and peptidase, were down-regulated in MTX-treated rats, as reported previously [8,9], and were restored only by E64. Proteasome-mediated proteolysis is involved in the regulation of many cell pathways [23]. Thus, the preservation of chymotrypsin-like and peptidase activities of proteasome by cathepsin inhibitors may be beneficial and could contribute to preserving the activity of various metabolic pathways. Interestingly, we recently reported the beneficial effects of a specific diet in this model that were associated with a decrease of cathepsin D activity and preservation of proteasome activities [13].

In summary, our study revealed that cathepsin inhibition preserved body weight and prevented intestinal side effects of chemotherapy in methotrexate-treated rats. Whether these results are also found in tumour-bearing animals should be evaluated further, as well as the effect of cathepsin inhibition on chemosensitivity of tumour cells.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Nestlé Research Centre, Lausanne, Switzerland and by ADEN EA4311, University of Rouen.

Disclosure

None to declare.

References

- 1.Logan RM, Gibson RJ, Bowen JM, Stringer AM, Sonis ST, Keefe DM. Characterisation of mucosal changes in the alimentary tract following administration of irinotecan: implications for the pathobiology of mucositis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;62:33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keefe DM, Cummins AG, Dale BM, Kotasek D, Robb TA, Sage RE. Effect of high-dose chemotherapy on intestinal permeability in humans. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;92:385–9. doi: 10.1042/cs0920385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keefe DM, Brealey J, Goland GJ, Cummins AG. Chemotherapy for cancer causes apoptosis that precedes hypoplasia in crypts of the small intestine in humans. Gut. 2000;47:632–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.5.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logan RM, Stringer AM, Bowen JM, Gibson RJ, Sonis ST, Keefe DM. Serum levels of NFkappaB and pro-inflammatory cytokines following administration of mucotoxic drugs. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1139–45. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carneiro-Filho BA, Lima IP, Araujo DH, et al. Intestinal barrier function and secretion in methotrexate-induced rat intestinal mucositis. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:65–72. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000011604.45531.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stringer AM, Gibson RJ, Logan RM, et al. Chemotherapy-induced diarrhea is associated with changes in the luminal environment in the DA rat. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:96–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stringer AM, Gibson RJ, Logan RM, Bowen JM, Yeoh AS, Keefe DM. Faecal microflora and beta-glucuronidase expression are altered in an irinotecan-induced diarrhoea model in rats. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1919–25. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.12.6940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boukhettala N, Leblond J, Claeyssens S, et al. Methotrexate induces intestinal mucositis and alters gut protein metabolism independently of reduced food intake. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E182–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90459.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leblond J, Le Pessot F, Hubert-Buron A, et al. Chemotherapy-induced mucositis is associated with changes in proteolytic pathways. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:219–28. doi: 10.3181/0702-RM-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hausmann M, Obermeier F, Schreiter K, et al. Cathepsin D is up-regulated in inflammatory bowel disease macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;136:157–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menzel K, Hausmann M, Obermeier F, et al. Cathepsins B, L and D in inflammatory bowel disease macrophages and potential therapeutic effects of cathepsin inhibition in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146:169–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03188.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leblond J, Hubert-Buron A, Bole-Feysot C, Ducrotte P, Dechelotte P, Coeffier M. Regulation of proteolysis by cytokines in the human intestinal epithelial cell line HCT-8: role of IFNgamma. Biochimie. 2006;88:759–65. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boukhettala N, Ibrahim A, Claeyssens S, et al. A diet containing whey protein, glutamine and TGFβ modulates gut protein metabolism during chemotherapy-induced mucositis in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2172–81. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visekruna A, Joeris T, Seidel D, et al. Proteasome-mediated degradation of IkappaBalpha and processing of p105 in Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3195–203. doi: 10.1172/JCI28804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzpatrick LR, Small JS, Poritz LS, McKenna KJ, Koltun WA. Enhanced intestinal expression of the proteasome subunit low molecular mass polypeptide 2 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:337–48. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0796-7. discussion 348–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue S, Nakase H, Matsuura M, et al. The effect of proteasome inhibitor MG132 on experimental inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:172–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coeffier M, Gloro R, Boukhettala N, et al. Increased proteasome-mediated degradation of occludin in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1181–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant PW, Lennon-Dumenil AM, Fiebiger E, Lagaudriere-Gesbert C, Ploegh HL. Proteolysis and antigen presentation by MHC class II molecules. Adv Immunol. 2002;80:71–114. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(02)80013-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briozzo P, Badet J, Capony F, et al. MCF7 mammary cancer cells respond to bFGF and internalize it following its release from extracellular matrix: a permissive role of cathepsin D. Exp Cell Res. 1991;194:252–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(91)90362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koike M, Nakanishi H, Saftig P, et al. Cathepsin D deficiency induces lysosomal storage with ceroid lipofuscin in mouse CNS neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6898–906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaidi N, Burster T, Sommandas V, et al. A novel cell penetrating aspartic protease inhibitor blocks processing and presentation of tetanus toxoid more efficiently than pepstatin A. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:243–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaidi N, Maurer A, Nieke S, Kalbacher H. Cathepsin D: a cellular roadmap. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;376:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]