Abstract

The objective of this case-control study of 242 reproductive-age women was to determine the concentration of afamin in the serum and peritoneal fluid of women with and without endometriosis and to test afamin as a diagnostic marker of endometriosis. Afamin levels were altered significantly in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis compared with disease-free controls, correlated with vitamin E levels, and are consistent with increased oxidative stress in the peritoneal cavity of women with endometriosis.

Endometriosis is estimated to affect 2% to 18% of reproductive-age women and upwards of 40% of women with infertility (1). Oxidative stress has been implicated as a component of the inflammatory reaction seen in endometriosis. Retrograde menstruation may carry pro-oxidant factors, including heme and iron, into the peritoneal cavity (2). Consequently, peritoneal fluid (PF) of women with endometriosis contains increased levels of markers of lipid peroxidation and of enzymes involved in the generation of reactive oxidant species (3, 4).

Vitamin E belongs to the family of nonenzymatic antioxidants and has been shown to be bound to afamin, its specific carrier protein in extravascular fluids (5). Subsequently, afamin was demonstrated to be present abundantly in follicular fluid, where its concentration correlated significantly with vitamin E levels, suggesting a possible role in oocyte development (6).

Murphy et al. (3) showed that vitamin E levels were significantly lower in the PF of women with endometriosis, attributing this finding to a local decrease of antioxidants caused by excessive oxidative stress. In a recent publication, Lambrinoudaki et al. (7) demonstrated that several markers of oxidative stress are elevated in the serum of women with endometriosis, suggesting a systemic phenomenon. Recently, we found a nonsignificant trend to lower serum afamin levels in women with benign gynecologic inflammatory conditions, including endometriosis, compared with healthy controls (8, 9).

The objectives of this study were [1] to determine whether afamin levels correlate with vitamin E levels in pelvic PF; [2] to test the hypothesis that concentrations of afamin in the PF, and perhaps also in serum, are lower in women with endometriosis compared with those without endometriosis; and [3] to test the potential use of afamin as a diagnostic marker of endometriosis, comparing it with CA-125, the most widely accepted marker of endometriosis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Pennsylvania and the Medical University of Innsbruck, and written informed consent was obtained. We included women 18 to 48 years of age undergoing surgery for infertility, pelvic pain, tubal sterilization or reversal, or other benign indication. We excluded women with known rheumatologic diseases or acute or chronic infections (including HIV) and those taking long-term anti-inflammatory medications. We did not exclude the relatively few women who were taking antidepressants (N = 12), antihypertensives (N = 11), antihistamines (N = 15), thyroid medications (N = 10), or inhaled bronchodilators (N = 4). These were distributed approximately evenly among groups.

Blood and PF were collected in the perioperative period, and endometriosis was recorded and staged according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine scoring system (10). The timing of surgery was as follows: 63% and 58% follicular phase, 22% and 26% luteal phase, and the remaining unknown, for the endometriosis and control groups, respectively.

Concentrations of afamin were quantified in serum and PF in duplicate by sandwich-type ELISA, as previously described (5, 6). CA-125 was measured in duplicate in serum and PF with use of ELISA kits (Panomics, Inc., Redwood City, CA, and Abbott, Inc., Vienna, Austria). Vitamin E was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography–ultraviolet (Chromsystems, Munich, Germany). Total protein content was measured in PF with use of a micro-bicinchoninic protein assay (BCA; Pierce, Inc., Rockford, IL).

Baseline characteristics of the two groups were compared with use of t-test, χ2, and Fisher's exact test, where appropriate. Mean concentrations of afamin and CA-125 were compared between groups with use of nonparametric tests: the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney tests. Bivariate relations were analyzed with the Spearman correlation coefficient and multivariate relations with a stepwise linear regression based on Akaike's information criterion. Multivariate analyses were performed to predict the presence of endometriosis and of infertility, accounting for missing values. The independent variables used were age, endometriosis, pelvic pain, infertility, serum afamin, serum CA-125, and PF afamin/PF protein. Sensitivity and specificity for afamin and CA-125 (log transformed) were assessed with receiver operating characteristic curves (11). Statistical analyses were performed with use of the laboratory results of serum analyzed from all 242 study subjects and the results of PF that had been procured from 160 of the study subjects (stage I = 49, stage II = 22, stage III = 14, stage IV = 21, controls = 54).

Of the 143 women in the endometriosis group, 66 (46%) had stage I, 22 (15%) stage II, 21 (15%) stage III, and 34 (24%) stage IV disease. The primary indication for surgery was pain in 93 (65%) and 23 (23%) and infertility in 42 (29%) and 37 (37%) in the endometriosis and control groups, respectively. The control group comprised 99 women without endometriosis. Sixty-nine of these had symptoms and had the following operative diagnoses: 11 myoma, 11 adhesive disease, 8 hydrosalpinx, 5 ovarian cyst, 2 paratubal cyst, 1 corpus luteum, 1 other (Müllerian anomaly), 29 no visible pelvic pathology. Thirty women in the control group were symptom free and underwent tubal ligation–reanastomosis surgery. In certain analyses, therefore, we further separated the control group into a symptomatic (infertility or pain, N = 69) and a symptom-free “healthy” subgroup (N = 30).

We found that PF afamin concentration correlated significantly with the PF vitamin E concentration (r = 0.635, 95% confidence interval 0.504–0.737, P<.0001). There were no differences in PF vitamin E–protein concentrations between women with and without endometriosis, regardless of stage of disease.

Mean concentrations of serum afamin were similar between the endometriosis and control groups, 63.36 ± 1.50 μg/mL and 63.86 ± 1.61 μg/mL, respectively. There were no differences in serum afamin concentrations between groups when separated by stage of endometriosis.

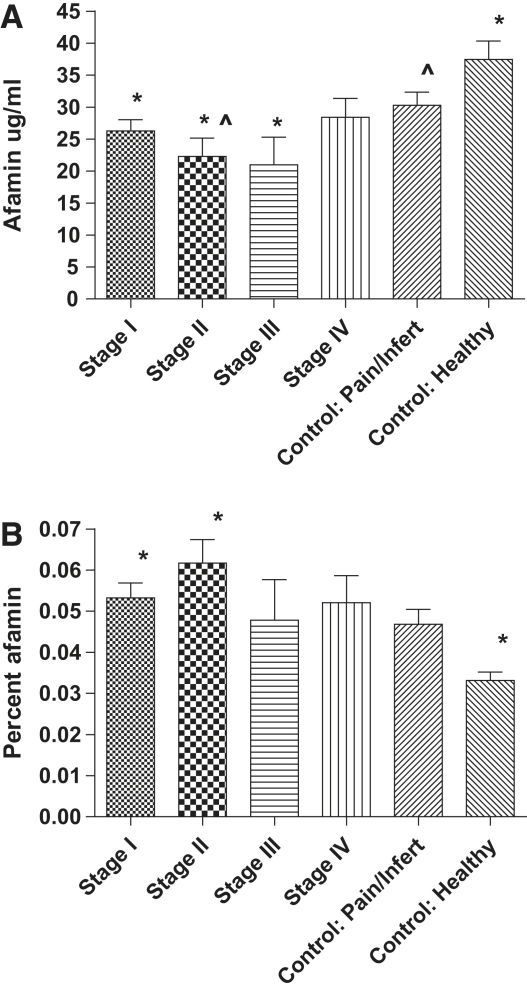

Peritoneal fluid afamin levels, however, were significantly different between the two groups (25.87 ± 1.41 μg/mL and 31.91 ± 1.88 μg/mL, P=.012). The mean concentrations of PF afamin were different, with stage III endometriosis having the lowest PF afamin (20.68 ± 4.63 μg/mL) and the asymptomatic controls the highest (37.45 ± 2.89 μg/mL) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Absolute PF afamin levels by stage of endometriosis and in the control group, by presence of symptoms. ∗Difference (P<.05) between stage I, II, III, and Control: Healthy. ^Difference (P<.05) between stage II and Control: Pain/Infert. (B) Afamin as a percentage of total PF protein (afamin/total protein) by endometriosis stage and control groups ∗Difference (P<.01) between stage I, stage II, and Control: Healthy.

To control for potential cycle-dependent PF volume differences and for a potential dilution effect in the 10 cases of hysteroscopic irrigation with normal saline solution before laparoscopy, we determined the protein content of the PF samples and then calculated the ratio of afamin to total protein, which we report as a percentage of afamin of PF protein. This relative afamin value is the one we used for further analyses.

Interestingly, we found substantial differences in the total PF protein content between groups, suggesting that the PF is more diluted in subjects with endometriosis. Thus, although the afamin/total protein in the PF remained significantly different between groups, the levels were nearly converse to those we observed when we only measured the absolute concentration of PF afamin (Fig. 1B).

With use of receiver operating characteristic curves, the area under the curve for afamin/total protein for the diagnosis of endometriosis was 0.601 (95% confidence interval 0.506–0.697, P=.045). In comparison, the area under the curve for serum CA-125 was 0.634 (95% confidence interval 0.563–0.705, P=.0005). There was no statistically significant difference in PF CA-125 concentrations between groups. Neither serum nor PF afamin levels correlated with their respective CA-125 levels (Spearman r = 0.01, P=.87; Spearman r = −0.01, P=.82).

The Akaike's information criterion optimal multivariable logistic model for predicting endometriosis included as predictors pelvic pain, serum afamin, serum CA-125, and PF afamin/PF total protein, but serum afamin was statistically not significant (P=.17). The odds of endometriosis rose by 60% with a doubling of serum CA-125 (odds ratio = 1.60, P=.0003) and were reduced by only 2% if serum afamin rose by one unit (odds ratio = 0.98, P=.17). Patients with pelvic pain had a more than four times higher risk of endometriosis than patients without pelvic pain (odds ratio = 4.18, P<.0001). The odds of endometriosis rose by 24% if PF afamin/PF total protein rose by 1% (unit) (odds ratio = 1.24, P=.028).

The stepwise logistic regression method for predicting infertility did not find any predictors; neither CA-125, serum afamin, endometriosis, nor any of the other covariates were found to reliably predict infertility. On multivariate analysis, PF afamin/PF protein was not predictive of infertility among the subset of subjects with endometriosis.

In conclusion, we were able to demonstrate for the first time that afamin concentration is strongly correlated with vitamin E concentration also in PF, a correlation that we previously demonstrated in other extravascular fluids such as follicular fluid and cerebrospinal fluid (6). We found that afamin makes up a higher percentage of the protein content of PF in subjects with endometriosis. This difference was especially pronounced when comparing those with stage I and II disease with healthy, asymptomatic control subjects. Subjects with stage III and IV disease and endometriosis-free subjects with pelvic pain and/or infertility (symptomatic control subgroup) appeared to have intermediate (though not statistically significant) PF afamin concentrations.

The calculation of greater amounts of afamin in lower-stage endometriosis appears contradictory to the single publication on this subject (3), which might be due to the very small study size of that work. We hypothesize that the higher afamin PF content of the PF protein in stage I and II endometriosis may be a reflection of a more acute stage of disease and signify an active recruitment of antioxidants, including vitamin E, to this local inflammatory environment. Conversely, the chronic state of higher-stage endometriosis is associated with less active inflammation and thus lower concentrations of antioxidants. It follows that healthy control subjects have the lowest levels of the antioxidant in the PF. These findings confirm previous reports of endometriosis causing localized inflammation and oxidative stress in the peritoneal cavity, albeit this inflammation may be disease stage specific (5, 12, 13).

On logistic regression analysis, CA-125 and the clinical presence of pelvic pain were both better predictors of endometriosis than either serum afamin or PF afamin/PF protein. To our surprise, none of the variables that we evaluated were predictive of infertility.

In summary, we found differences in PF afamin levels between women with and without endometriosis, a finding that confirms the link between the disease and localized oxidative stress. Future studies further evaluating the association between markers of oxidative stress and endometriosis-associated infertility and ones investigating the potential therapeutic benefits of antioxidants are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Ms. Linda Fineder, Ms. Andrea Sapinsky, and Ms. Ruth Lenners for excellent technical assistance and to Stephan Kropshofer, M.D., and Sigfried Fessler, M.D., for help in specimen collection.

Footnotes

K.T.B. is a consultant for Pfizer and Swiss Precision Diagnostics and a clinical trial investigator for Boehringer Ingelheim, Third Wave, Wyeth-Ayerst, and Xanodyne. H.D. is owner of Vitater Biotechnology. B.E.S. has nothing to disclose. T.C. has nothing to disclose. H.B. has nothing to disclose. C.S. has nothing to disclose. G.D. has nothing to disclose. L.W. has nothing to disclose.

Supported by grants from the Jubiläumsfonds of the Austrian National Bank to B.E.S. (Project 12724) and H.D. (12529) and from the Austrian Science Fund to H.D. (P19969-B11).

References

- 1.Missmer S.A., Cramer D.W. The epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003;30:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(02)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Langendonckt A., Casanas-Roux F., Donnez J. Oxidative stress and peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:861–870. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)02959-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy A.A., Santanam N., Morales A.J., Parthasarathy S. Lysophosphatidyl choline, a chemotactic factor for monocytes/T-lymphocytes is elevated in endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2110–2113. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.6.4823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ota H., Igarashi S., Tanaka T. Xanthine oxidase in eutopic and ectopic endometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:785–790. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)01670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voegele A.F., Jerkovic L., Wellenzohn B., Eller P., Kronenberg F., Liedl K.R. Characterization of the vitamin E–binding properties of human plasma afamin. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14532–14538. doi: 10.1021/bi026513v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jerkovic L., Voegele A.F., Chwatal S., Kronenberg F., Radcliffe C.M., Wormald M.R. Afamin is a novel human vitamin-E–binding glycoprotein; characterization and in vitro expression. J Proteome Res. 2005;4:889–899. doi: 10.1021/pr0500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambrinoudaki I.V., Augouela A., Christodoulakos G.E., Economou E.V., Kaparos G., Kontoravdis A. Measurable serum markers of oxidative stress response in women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson D., Craven R.A., Hutson R.C., Graze I., Lueth P., Tonge R.P. Proteomic profiling identifies afamin as a potential biomarker for ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:7370–7379. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dieplinger H., Ankerst D.P., Burges A., Lenhard M., Lingenhel A., Fineder L. Afamin and apolipoprotein A-IV: novel protein markers for ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:1127–1133. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Society for Reproductive Medicine Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:817–821. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)81391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harley J.A., Mcneill B.J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pizzo A., Salmeri F.M., Ardita F.V., Sofo V., Tripepi M., Marsico S. Behavior of cytokine levels in serum and peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2002;54:82–87. doi: 10.1159/000067717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheong Y.C., Shelton J.B., Laird S.M., Richmond M., Kudesia G., Li T.C. IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-alpha concentrations in the peritoneal fluid of women with pelvic adhesions. Hum Reprod. 2002;7:69–75. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]