Abstract

This study reports experimental measurements of solute diffusivity and partition coefficient for various solute concentrations and gel porosities, and proposes novel constitutive relations to describe these observed values. The longer-term aim is to explore the theoretical ramifications of accommodating variations in diffusivity and partition coefficient with solute concentration and tissue porosity, and investigate whether they might suggest novel mechanisms not previously recognized in the field of solute transport in deformable porous media. The study implements a model transport system of agarose hydrogels to investigate the effect of solute concentration and hydrogel porosity on the transport of dextran polysaccharides. The proposed phenomenological constitutive relations are shown to provide better fits of experimental results than prior models proposed in the literature based on the microstructure of the gel. While these constitutive models were developed for the transport of dextran in agarose hydrogels, it is expected that they may also be applied to the transport of similar molecular weight solutes in other porous media. This quantification can assist in the application of biophysical models that describe biological transport in deformable tissues, as well as the cell cytoplasm.

Introduction

In many biological tissues, it has been shown that dynamic loading can promote biosynthetic activity and prevent tissue degradation. For example, in articular cartilage, cyclical loading in the range of physiologically relevant frequencies promotes glycosaminoglycan and protein synthesis, whereas static loading inhibits this process 48. This type of response has also been observed in cartilage tissue engineering studies, where dynamic compression has been shown to promote better mechanical properties in comparison to unloaded controls 36–38. It is generally believed that dynamic loading may increase cellular activity via two pathways: A mechano-transduction pathway whereby cells respond to the loading environment directly, through integrin-mediated responses or molecular conformational changes transduced to the nucleus; and an enhanced solute transport pathway whereby loading increases the supply of nutrients, growth factors, cytokines, morphogens, etc., leading to greater matrix synthesis.

In an effort to elucidate the role of solute transport in dynamically loaded porous tissues, we previously extended the framework of mixture theory 6, 7, 16, 25, 39, 55 to specifically accommodate the interaction of solutes with the solid matrix of a tissue 35, generalizing the classical framework of Fick’s diffusion where solutes only interact with the solvent. In this framework, two diffusion coefficients emerged naturally from the formulation, one that describes solute diffusion in free solution, involving the frictional drag between solute and solvent, and another that describes solute diffusion in the porous tissue, also involving the frictional drag between solute and solid matrix. Thus, this theoretical framework could naturally describe the well-attested observation that solutes diffuse at different rates inside a porous medium than in free solution 14.

An intriguing theoretical prediction emerged from this framework, which had not been previously anticipated 35: Accordingly, under sustained dynamic loading, this theory predicted that the solute concentration inside the tissue would rise to values far exceeding those achieved under passive diffusion (no loading). In effect, the theory suggested that dynamic loading could pump the solute from the external bathing solution into the tissue, against its concentration gradient, thereby describing an active transport process. Since this outcome had never been previously reported from experiments, we subsequently performed a series of studies where agarose hydrogels of various porosities were exposed to dextran solutions of various molecular weights, and confirmed these earlier theoretical predictions unequivocally 2. For certain combinations of gel concentrations and dextran molecular weights, solute uptake was enhanced up to sixteen-fold relative to passive diffusion, and results suggested that higher values could be achieved with longer loading durations. Thus, a fundamental mechanism of active transport in deformable porous tissues was discovered through these studies, initially motivated from theory. Importantly, the theory would not have predicted these enhancements in solute uptake if the diffusive drag between solute and solid matrix had been neglected; indeed, the pumping mechanism described by this theory is contingent on the solid matrix exchanging momentum with the solute.

Another interesting theoretical development advanced in this earlier study 35 was the formulation of a constitutive relation for the chemical potential of solutes that explicitly accommodates the well-known phenomenon of solute partitioning in a porous medium 27, 42. Though well recognized experimentally, it appears that the concept of partitioning had not been previously incorporated into theoretical frameworks of transport in porous media. In a subsequent theoretical study, we adapted this framework to the analysis of osmotic loading of cells 5 and discovered that we could extend the classical model formulated by Kedem and Katchalsky 24: In the K-K model, which models the cell as a fluid-filled membrane, when a cell is loaded osmotically with a membrane-permeant solute, its volume decreases initially but eventually recovers to its initial value as the internal concentration of the membrane-permeating solute eventually rises to the external value. In our extended framework, the cell is modeled as a gel-filled membrane, where the membrane-permeant solute may be partially partitioned out of the porous gel (representing the cell protoplasm). A consequence of this partitioning is that the cell does not recover its initial volume at steady state, since a smaller cell volume is required to match the internal and external solute concentrations.

Thus, our theoretical framework predicted that partial volume recovery following osmotic loading with a membrane-permeant solute could be explained by passive mechanisms (solute partitioning). Prior experimental studies either overlooked this partial volume recovery 56 or attributed it to active transport processes 33 known to regulate cell volume 18. To verify that our theoretical framework described a feasible mechanism, we conducted osmotic loading experiments on alginate beads, using dextran solutions of various concentrations and molecular weights 1 and confirmed that partial volume recovery could indeed occur even in the absence of a membrane and active membrane transporters, in a manner fully consistent with the theory. We have since applied this framework to analyze the volumetric response of chondrocytes to various osmolytes with similar success 3.

A critical concept emerging from these prior studies is that suitably formulated theoretical frameworks for solute transport in porous deformable media may motivate novel hypotheses relevant to the study of biological tissues and cells, and guide the design of experiments to test these hypotheses. When combining solute transport with porous deformable media, we find that theoretical frameworks are still under development, since basic concepts long recognized from experiments (such as hindered solute diffusion, and solute partitioning in a porous medium) can be incorporated in a variety of ways into theory, sometimes yielding new and unexpected predictions. In the mixture framework extended in our recent studies 5, 35, it was assumed to a lowest-order approximation that solute diffusivity and partitioning are constant material properties in the model. However, it is known from experiments that these properties may vary significantly with solute concentration 28, 40, 44 and with gel porosity 12, 22, 28, 32, 46, 47. Indeed, osmotic loading of cells with membrane-permeant osmolytes may involve a wide range of concentrations in certain applications, ranging for example from 0 to 1.4 M 56. The resulting variations in diffusivity and partition coefficient can be described in the theory by incorporating suitable constitutive relations whose formulation needs to be deduced from experimental measurements.

Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to perform measurements of solute diffusivity and partition coefficient for various solute concentrations and gel porosities, and use constitutive relations to describe these observed values, proposing phenomenological formulations as required. The longer-term aim of this study is to explore the theoretical ramifications of accommodating variations in diffusivity and partition coefficient with solute concentration and tissue porosity, and investigate whether they might suggest novel mechanisms not previously recognized in the field of solute transport in deformable porous media.

Prior studies have proposed microstructurally motivated constitutive relationships between solute diffusivity and various parameters that include the gel fiber volume fraction 34, as well as the Stokes-Einstein radius of the solute, and the permeability of the gel to the solution 13, 17, 21, 22,45. These models are usually valid for very dilute solutions, although some extensions have been provided to adjust for the solute concentration 13, 15. Furthermore, the more accurate versions of these models 17, 21, 22 rely on a prior knowledge of the Darcy permeability of the gel to the solution, whose value needs to be determined from experiments. In contrast, in the continuum framework of mixture theory, knowledge of the microstructure of the gel and solute is not required explicitly. Constitutive models for the diffusivity and partition coefficient may be formulated as functions of the gel porosity and solute concentration alone, though it follows that the material coefficients appearing in these constitutive models will vary with the choice of solute type and molecular weight, as well as gel or porous medium type. Therefore, the constitutive models investigated in the current application differ in their scope from the prior literature.

The current experimental study implements a model transport system of agarose hydrogels to characterize the effect of solute concentration and hydrogel water content on the transport of dextran polysaccharides. Agarose hydrogels are commonly used as a porous medium in molecular transport studies 10, 22, 30, 46 and also serves as a promising scaffold material for cartilage tissue engineering 37. Dextran polysaccharides are readily available in a large range of molecular weights where they mimic the transport of various solutes and proteins. This study examines the dependence of the dextran diffusion coefficient as well as the equilibrium partition coefficient in agarose on solute concentration. Measurements of the diffusion coefficient are obtained from fluorescent recovery after photobleaching (FRAP). In order to facilitate the measurement of dextran transport properties at high concentrations, a technique is employed as previously described by Laurent et al. 28; solutions are prepared with dilute concentrations of fluorescein-conjugated dextran and supplemented with higher concentrations of unlabeled dextran of the same molecular weight. In principle, fluorescent intensity measurements of the conjugated species represent average properties of the solute, under the assumption that the dextran chemical properties are unaffected by conjugation.

The FRAP technique is commonly used to measure solute transport in membranes and other porous media. However, the implementation of this procedure can vary considerably in terms of bleaching parameters and recovery processing 54. Therefore, in this study, an additional experiment was conducted to directly measure the diffusivity of dextran in agarose; the radial uptake of dextran into agarose disks was experimentally monitored, modeled through Fick’s Law, and used to validate the FRAP protocol.

Methods

Materials

Type VII hydroxy-ethyl agarose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was cast at 2%, 4%, and 6% w/v in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Tracer solutions of 70 kDa and 10 kDa fluorescein conjugated dextran (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were prepared in PBS at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. These dilute tracer solutions were supplemented with non-conjugated dextran (Sigma) of equal molecular weight, yielding a broad range of solution concentrations (7 μM, 0.1 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 2 mM, 3mM for 70 kDa; 50 μM, 20 mM, 35 mM, and 50 mM for 10 kDa).

Diffusivity Measurements from FRAP

Fluorescent recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was used to measure the diffusivity of 10 kDa and 70 kDa dextran at all prepared concentrations in 2%, 4%, and 6% agarose hydrogels, as well as in free solution (n=3 per each gel porosity, and each dextran concentration group). Agarose disks (Ø4mm × 1.5 mm) were incubated in dextran solution for 24 hours and then placed in a modified Petri dish with a glass bottom to allow fluorescent imaging. While in the dish, samples were placed in a custom-made static loading device and subjected to a 10% axial compressive strain. A confocal microscope (Olympus IX70, Fluoview acquisition software) was used at a 488 nm laser emission with a 10× objective (3.04 μm/pixel) to image the center of the disk on its bottom surface focal plane. A narrow line (≈ 1.5 × 0.1 mm) was bleached across the sample at 100% laser intensity for 60 seconds and recovery scans at a 6% laser intensity were subsequently acquired at regular time intervals. For each image, a custom image processing routine (Matlab, Mathworks, Natick, MA) was used to obtain intensity profiles perpendicular to the bleached line. The one-dimensional diffusion equation for a Gaussian initial distribution can be modeled by

| (1) |

| (2) |

where the fluorescence intensity, I , is a function of time, t , and position along the profile, x ; M is the total amount of bleached species, and D is the diffusion coefficient 11, 52. A least-squares curve-fitting algorithm was used to extract D using these relations.

Partition Coefficient Measurements

Agarose hydrogel disks (Ø1.5 mm × 1.5 mm) of 2%, 4%, or 6% were incubated in 10 kDa or 70 kDa dextran solution at each of the prepared concentrations for 24 hours (n=3 per group). After this period, disks were placed in the custom loading device under a nominal compressive strain (≈ 1%) and exposed to the same dextran solution. A confocal image of half the circular cross-section and surrounding bathing solution was acquired on the bottom surface focal plane of the disk. A custom Matlab routine was used to determine the average fluorescent intensity in the external bathing solutiong as well as the radially averaged intensity in the disk. The solute concentration in the disk, c(r,t) , normalized to the bathing concentration cbath , was calculated as a ratio of the intensity in the disk, I (r,t) , to that in the bathing solution, Ibath :

| (3) |

where ϕw is the water volume fraction of the gel. At equilibrium, the solute concentration in the gel becomes uniform, cavg , and this formula yields the partition coefficient κ of dextran in the gel,

| (4) |

Measurements from Disk Absorption

A dextran-free agarose disk (Ø1.5mm × 1.5mm) was placed in the custom loading device under a 10% compressive strain and exposed to a dilute bathing solution (10 kDa or 70 kDa fluorescein conjugated dextran − 0.5 mg/mL; n=3 per molecular weight). The testing chamber was covered and bathing solution was circulated at a rate of 25 mL/min with a peristaltic pump (Manostat, Vera Varistaltic). Confocal images of half the disk’s circular cross-section and surrounding bathing solution were acquired at the disk’s bottom focal plane at regular time intervals under the aforementioned settings. For each image, the concentration inside the disk normalized to the bathing solution was determined at radial positions ( r / a= 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75) through Eq. (3). The normalized spatial-temporal response for one-dimensional radial diffusion can be modeled by Fick’s Law,

| (5) |

where κ is the partition coefficient of the gel, a is the disk radius, J0 and J1 are Bessel functions, and γm is the m-th root of J0 (γ ) . This relation was simultaneously curve-fit to the responses at all four radial positions to extract the diffusion coefficient D and partition coefficient κ .

Results

Diffusivity Measurements from FRAP

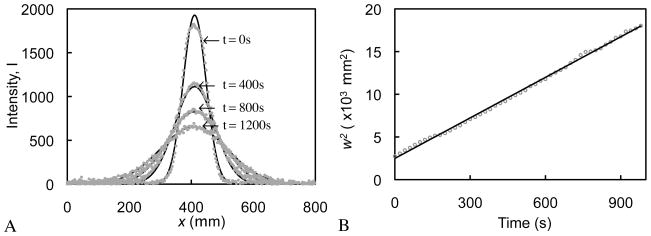

Samples subjected to the FRAP procedure exhibited a photobleached line whose cross-section depicted an intensity profile with a Gaussian distribution that decayed over time (Fig. 1). Equation (1) yielded w2 for each profile, which was observed to vary linearly with time (R2= 0.992 ± 0.02 for all samples), allowing for the determination of the diffusion coefficient from Eq.(2). For both dextran molecular weights, at the dilute concentration, the diffusivity was found to be highest in free solution and decreased exponentially with increasing agarose gel concentration (Fig. 2). For each agarose gel concentration, the diffusivity was also found to decrease exponentially with increasing dextran concentration. For both dextran molecular weights, the dependence of the diffusivity on gel water content, ϕw , and solute concentration, c , was curve-fitted to the constitutive relation

Fig. 1.

(A) Representative intensity profiles of recovery of bleached line during FRAP, at four selected time points. Solid curves represent curve-fits of Eq.(1) to each profile, producing a value for w2 at each time point. (B) Plot of w2 versus time for the same FRAP test. The slope of the line is proportional to the diffusion coefficient according to Eq.(2).

Fig. 2.

(A) Diffusion coefficient versus dextran concentration for 70 kDa dextran. Solid curves represent curve-fit of Eq.(6) to the experimental data. (B) Diffusion coefficient versus dextran concentration for 10 kDa dextran. Solid curves represent curve-fit of Eq.(6) to the experimental data.

| (6) |

where D0 is the diffusivity in free solution (when ϕw = 1 ) and in the limit of zero concentration, and αD and cD are governing material constants. The exponential form of this constitutive relation is motivated by the experimental observations. Furthermore, this function reduces to reasonable values under various limiting conditions: For very dilute solutions ( c → 0), the resulting expression reduces to a special case of the constitutive model for ion diffusivity proposed by Gu et al. 17 (see their equation 11); in the limit of very high solute concentrations ( c → ∞) it predicts zero diffusivity ( D → 0); in the limit of zero porosity (ϕw → 0 ) it also predicts zero diffusivity ( D → 0); and in the limit of a pure solution (ϕw → 1) it predicts only an exponential dependence on solute concentration, with D → D0 in the limit of very dilute solutions. The two-dimensional curve-fit of Eq.(6) to the experimental data (Fig. 2) yielded the values listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Curve-fitted parameters and coefficients of determination for the diffusion coefficient from Eq.(6) and the partition coefficient from Eqs.(7)–(8).

| Diffusion Coefficient | Partition Coefficient | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mw | D0 (μm2/s) | αD | cD (mM) | R2 | α0 | α∞ | cκ (mM) | R2 |

| 70kDa | 45.87 | 27.52 | 1.10 | 0.977 | 48.62 | 19.98 | 0.95 | 0.990 |

| 10kDa | 122.52 | 17.87 | 15.72 | 0.976 | 23.11 | 16.24 | 10.75 | 0.937 |

Partition Coefficient Measurements

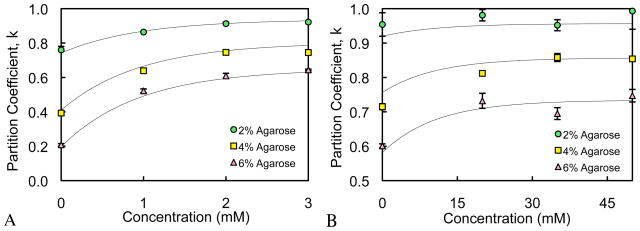

For partition coefficient measurements at dilute concentrations, κ was found to be consistently higher for the lower molecular weight dextran, and decreased with increasing agarose gel concentration (Fig. 3). For all samples, κ was found to increase exponentially in response to increasing dextran concentration, nearly reaching a steady-state value at the highest dextran concentration. For both dextran molecular weights, the response of the partition coefficient versus gel water content, ϕw , and solute concentration, c , was also curve-fitted to an empirical constitutive relation,

Fig. 3.

(A) Partition coefficient versus dextran concentration for 70 kDa dextran. Solid curves represent curve-fit of Eqs.(7)–(8) to the experimental data. (B) Partition coefficient versus dextran concentration for 10 kDa dextran. Solid curves represent curve-fit of Eqs.(7)–(8) to the experimental data.

| (7) |

where,

| (8) |

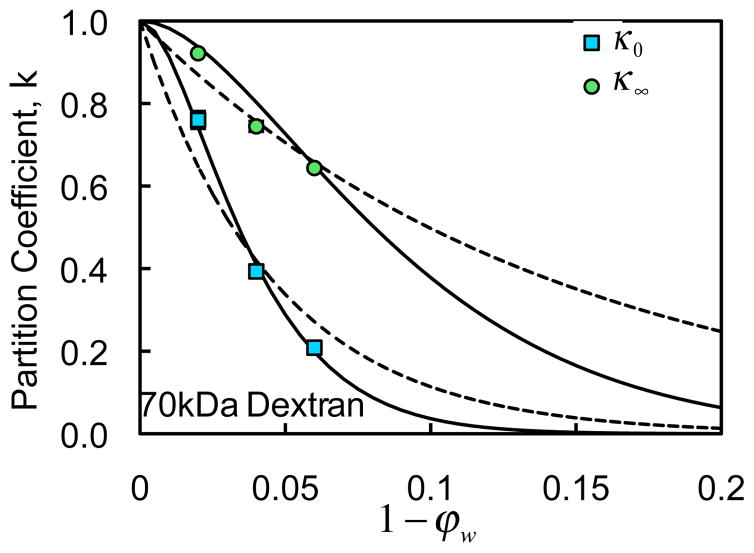

κ0 is the partition coefficient in the limit of zero concentration and κ∞ is the partition coefficient in the limit of large concentrations; α0 α∞ , and cκ are governing material constants obtained from curve-fitting (Table 1). The expressions in Eq.(8) are valid over the entire range 0 ≤ ϕw ≤ 1. The form of Eq.(7) is motivated by the observed exponential dependence of the partition coefficient on solute concentration; in the limit of very dilute solutions ( c → 0) it yields κ → κ0; and in the limit of very concentrated solutions ( c → ∞ ) it yields κ → κ∞. The form of the equations in Eq.(8) is motivated by the need to produce a sigmoidal response varying from κ = 0 to κ = 1 as the gel porosity ϕw increases from 0 to 1. This type of sigmoidal response (Fig. 4) is consistent with the expectation that pore sizes vary over a continuous probability distribution function, and that solutes may only occupy pores that are sufficiently large to accommodate them.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of experimental results and model fits for the partition coefficient in the limit of dilute (κ0) and high solute concentrations (κ∞), as a function of agarose gel solid content (1−ϕw ) for the 70 kDa dextran. Solid lines represent the sigmoidal models of Eq.(8) and dashed lines represent the exponential model of Ogston 41 as used by Tong and Anderson 53.

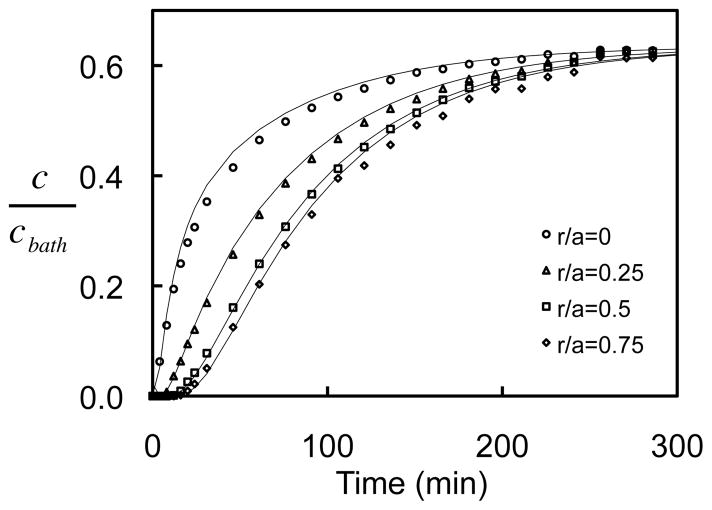

Measurements from Disk Absorption

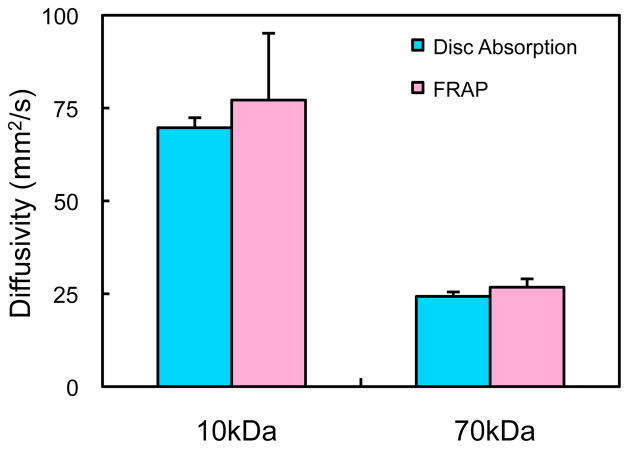

In cylindrical 2% agarose disks, the dextran concentration increased with time, reaching equilibrium faster at radial positions closer to the periphery of the disk (Fig. 5). Eq. (5) was simultaneously curve-fitted to four normalized positional uptake responses yielding mean ± standard deviation values of D= 24.3 ± 1.2 μm2/s, κ = 0.62 ± 0.03 for 70 kDa dextran (R2= 0.996 ± 0.002), and D= 69.7 ± 2.7 μm2/s, κ = 0.81 ± 0.02 for 10 kDa dextran (R2= 0.989 ± 0.004). For both molecular weights, the diffusivity values obtained from disk absorption were not statistically different (p>0.16) from the values obtained from FRAP in 2% agarose at dilute concentrations ( D= 26.8 ± 2.3, for 70 kDa dextran; D= 77.2 ± 18.0 for 10 kDa dextran, Fig. 7). However, the values obtained for κ were significantly lower than the measurements acquired from the aforementioned confocal imaging of equilibrated 2% agarose disks (κ =0.76 ± 0.02, for 70 kDa dextran; κ =0.95 ± 0.03, for 10 kDa dextran).

Fig. 5.

Representative case of normalized concentration uptake for 2% agarose exposed to 70 kDa dextran at 7 μM. Solid curves represent curve-fit of Eq.(5) to the experimental data.

Fig. 7.

Comparison of diffusivities of 10 kDa and 70 kDa dextran as measured from FRAP (Fig. 1) and disk absorption (Fig. 5), in the case of dilute concentrations in 2% agarose. No statistical differences were observed between the two methods (p>0.16).

Discussion

This experimental study characterizes the role of solute concentration on molecular transport in porous media through the investigation of dextran polysaccharides in agarose hydrogels. Results show that, as previously reported 13, increases in solute molecular weight and hydrogel concentration (1−ϕw ) decrease solute diffusivity D and the partition coefficient κ in the gel. It is also demonstrated that solute concentration c influences these transport properties as well. Increased solute concentrations decrease the diffusivity of dextran in the gel (Fig. 2), while increasing the partition coefficient (Fig. 3).

The constitutive models proposed for D(ϕw, c) and κ (ϕw , c) in this study, Eqs. (6)–(8), are able to faithfully describe the influence of all these factors on the diffusivity and partition coefficient of this transport system. A benefit of these models is supported by the near unity correlation coefficients in curve-fitting the experimental data (Table 1), as well as their ability to predict experimental trends previously reported in the literature.

The first observation from these experiments is that both the solute diffusivity and partition coefficient in the gel decrease with increasing gel concentration. The role of gel concentration in hindering molecular transport is commonly observed and attributed to hydrodynamic and steric factors 17, 22, 53, as well as electrostatic effects 13, 51. The decreased pore size found in denser gels promotes increased frictional interactions between solutes and the gel solid matrix, resulting in a decreased solute mobility as well as increased solute exclusion.

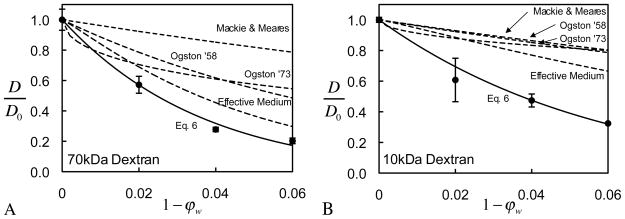

Many previously developed theoretical models have attempted to characterize this hindered diffusion of solutes in porous media at dilute concentrations. The framework proposed by Mackie and Meares 34 suggests that for small molecules, the hindered solute diffusivity depends only on the porosity of the solid network. This constitutive model does not provide adjustable parameters and, in principle, is applicable for small solutes only. Indeed, according to the data acquired in this study, this model significantly overestimates the diffusivity of dextran in agarose (Fig. 6). Other constitutive models have been proposed, which require prior knowledge of the pore size and assumptions about the pore shape (e.g., circular, rhomboidal, elliptical and rectangular cross-sections, or slit geometry), as reviewed by Deen 13; these models are more suitable for membranes than gels 22, and furthermore, since the pore size of the Type VII agarose gels used in this study is unknown, a direct comparison of the current results with these prior models is not attempted here.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of experimental results and various models for the hindrance to solute diffusion, D/D0 , in the limit of dilute dextran concentrations. (A) 70 kDa dextran, and (B) 10 kDa dextran. See text for description of various models.

Constitutive relations have also been proposed that relate the solute diffusivity to the gel solid fraction (1−ϕw ) and the ratio rs/rf of the solute’s Stokes-Einstein radius and the gel’s fiber radius, in the forms 41

| (9) |

and 43

| (10) |

These relations are applicable to dilute solutions; using rf = 1.9 nm for agarose 21, and rs = 4.7 nm for 70 kDa or rs = 1.7 nm for 10 kDa dextran, predictions from Eqs.(9)–(10) are compared to our experimental results in the case of dilute dextran concentrations, showing poor agreement for both dextran molecular weights (Fig. 6).

More recently, Phillips et al. 45 have proposed an effective medium approach for predicting solute hindrance in the gel, based on Brinkman’s equation 9. This formulation was further extended by Johnson et al. 22 in the form

| (11) |

where K is the Darcy permeability of the solution in the gel and S(f) is a steric factor calculated from the effective diffusivity of a molecule in an array of fibers. In their comparison to experimental data, they used a formulation obtained by Johansson and Löfroth 20,

| (12) |

and reported better agreement than with Eqs.(9)–(10). Indeed, a comparison of Eq.(11) against our experimental data, using values of κ from Johnson and Deen 23, similarly shows better agreement than Eqs.(9)–(10) in the case of 70 kDa dextran, though significant deviations from experiments remain apparent. With 10 kDa dextran, none of the models in Eqs.(9)–(11) provide satisfactory predictions.

In comparison, the phenomenological constitutive model of Eq.(6), shown in Fig. 6 in the limit of dilute solutions ( c → 0), fits the experimental data very faithfully. As mentioned above, this limiting case of Eq. (6) represents a special form of the model proposed by Gu et al. 17,

| (13) |

where α , β , a and n are material coefficients to be obtained from curve-fitting.

In summary, the comparisons presented in Fig. 6 demonstrate that the accuracy of constitutive models formulated based on assumptions about the microstructure is not guaranteed; these models must always be validated against experimental measurements. The approach advocated in this study, consistent with prior continuum formulations of transport problems in porous media 17, 19, 26, is to fit phenomenological constitutive relations to experimental data, rather than rely on microstructural models. Within this context, the formulation of Eq.(6) extends the existing models in the literature by also incorporating the effect of solute concentration on the hindrance within gels of various concentrations. It is remarkable that agreement across multiple values of solute concentrations c and gel porosities ϕw may be achieved with the simplicity of Eq. (6). Furthermore, unlike some of the models described in Eqs. (9)–(11), Eq. (6) predicts sensible limiting values over the entire range of ϕw ( 0 ≤ ϕw ≤ 1) and c (0 ≤ c < ∞ ). In this curve-fitting approach, the material coefficients must be obtained experimentally for each combination of gel (or tissue) type and solute.

The role of solute concentration on the hindering of solute diffusion in the agarose gel is also an expected finding based on previously reported investigations. Prior studies have found a decrease in the intradiffusion coefficient of dextran solutes in highly concentrated dextran solutions 28, as well as in the diffusivity of dextran in concentrated solutions of other polymers 44. These findings have been attributed to additional hydrodynamic frictional interactions due to added solutes in solution. However, most of these studies have investigated this diffusion hindrance only in the absence of a solid network. The results from the current study demonstrate that for increasing solute concentration in the presence of a solid gel network, the dextran diffusivity exponentially decreases towards a value of zero.

It is interesting to note that in a few studies where this solute concentration-dependent behavior in gels has been investigated, it has been reported that the diffusion coefficient D increases slightly with increasing solute concentration c 10, 50, contrary to our findings (Fig. 2). However, these earlier studies were conducted under different experimental conditions where the observed diffusing medium was initially solute-free (akin to our disk absorption studies for dilute dextran concentrations, Fig. 5). One of the inherent benefits of using FRAP for our experiments is that it provides a direct method for tracing the diffusion of solutes even while the dextran concentration in the diffusing medium remains unchanged; indeed, FRAP tracks the diffusion of unbleached dextran molecules through a region initially comprised of bleached dextran molecules. This technique avoids potential confounding experimental artifacts that arise from large variations in dextran concentration, such as alterations in solute diffusivity and partitioning with transient changes in concentration, as well as transient contraction of the deformable hydrogel resulting from osmotic effects 1.

It is also encouraging to observe an independent validation of the FRAP protocol used in this study. For dilute dextran concentrations (which avoid the potential artifacts mentioned above), statistically equivalent values of diffusivity were observed through the modeling of radial uptake into a cylindrical disk (Fig. 7). In contrast, the observation that the partition coefficients obtained under the equilibrium measurements were higher than those obtained from the disk absorption study most likely results, in part, from the difference in the applied compressive strain (1% strain in the experiment used exclusively to measure the equilibrium partition coefficient, Fig. 3, versus 10% strain in the disk absorption experiment used to measure diffusivity and partition coefficient, Fig. 5). Additionally, the measured free solution diffusivity for 70 kDa dextran is in the same range as values reported in previous studies 31, 44.

In the case of the partition coefficient κ , past studies have explored either the influence of gel porosity ϕw 53, or the influence of solute concentration c 30. Tong and Anderson used the exponential form of Ogston 41 (Eq.(9) with D replaced by κ and D0 set to one) to fit their experimental data by adjusting the fiber radius, achieving good fits. However, for the experimental data obtained in the current study, κ was observed to reach unity for values of ϕw < 1, making that type of exponential fit unsuitable for this kind of response, as shown in Fig. 4 in the limiting cases of dilute solutions and concentrated solutions. In order to capture the observed response as ϕw approaches unity, a novel formulation was implemented as shown in Eq.(8) and Fig. 4, to accommodate the role of the gel porosity. In the opposite limit, as ϕw approaches zero, this relation forces κ to similarly reduce to zero, as would be expected. The effect of solute concentration on κ has been modeled using an excluded volume theory 29, 30, which uses microstructural information such as solute and gel fiber size and requires the numerical solution of a couple system of nonlinear equations. In the current study, the dependence of κ on c is described faithfully (Fig. 3) by the simple exponential relation of Eq.(7), a relation that holds consistently over the entire experimental range of values of ϕw using only a single curve-fitted parameter cκ. Thus, the novel constitutive relation presented in Eqs. (7)–(8) presents many advantages, including relative simplicity, no reliance on prior knowledge of the material microstructure, and a well-behaved response over the entire range of ϕw and c . However, the corresponding material coefficients must be obtained experimentally for each combination of gel (or tissue) and solute.

It is also interesting that while the solute diffusion coefficient was observed to decrease with increasing dextran concentration, the equilibrium partition coefficient of dextran in agarose was found to increase. This counterintuitive finding is consistent with previously obtained measurements for a variety of molecules in porous media 8, 30, 49. Originally, this effect was attributed to a decrease in the solute dimensions that can occur in highly concentrated solutions, which would reduce steric exclusion from gel pores 50. However, as this behavior has also been observed with globular protein molecules, which possess a relatively fixed morphology, a more recent theoretical framework attributes this effect to electrostatic interactions between the solutes and pore walls 4.

In summary, the empirical constitutive relations for D(ϕw , c) and κ (ϕw , c) formulated in this study allow for the accurate characterization of the influence of gel and solution concentration on solute transport properties. While these constitutive models were developed for the transport of dextran in agarose hydrogels, it is expected that they may also be applied to the transport of similar molecular weight solutes in other porous media. This quantification of dependence of molecular diffusion and partitioning on solute and hydrogel concentrations can assist in the application of models that describe biological transport in deformable tissues, as well as the cell cytoplasm.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported with funds from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the US National Institutes of Health (AR 46532 and AR 52871).

References

- 1.Albro MB, Chahine NO, Caligaris M, Wei VI, Likhitpanichkul M, Ng KW, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Osmotic loading of spherical gels: a biomimetic study of hindered transport in the cell protoplasm. J Biomech Eng. 2007;129:503–510. doi: 10.1115/1.2746371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albro MB, Chahine NO, Li R, Yeager K, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Dynamic loading of deformable porous media can induce active solute transport. J Biomech. 2008;41:3152–3157. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albro MB, Chao PH, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Partial volume recovery of chondrocytes upon osmotic loading explained by the cytoplasm's passive steric exclusion of select solute species. Trans Annu Mtg Orthop Res Soc. 2007;32:151. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson J, Brannon J. Concentration dependence of the distribution coefficient for macromolecules in porous media. J Polym Sci Polym Phys Ed. 1981;19:405–421. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ateshian GA, Likhitpanichkul M, Hung CT. A mixture theory analysis for passive transport in osmotic loading of cells. J Biomech. 2006;39:464–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowen RM. Theory of mixtures. New York: Academic Press; p. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bowen RM. Incompressible porous media models by use of the theory of mixtures. International Journal of Engineering Science. 1980;18:1129–1148. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brannon J, Anderson J. Concentration effects on partitioning of dextrans and serum albumin in porous glass. J Polym Sci. 1982;20:857–865. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinkman HC. A calculation of the viscous force exerted by a flowing fluid in a dense swarm of particles. Appl Sci Res. 1949;A1:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buck KKS, Dungan SR, Phillips RJ. The effect of solute concentration on hindered gradient diffusion in polymeric gels. J Fluid Mech. 1999;396:287–317. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crank J. The Mathematics of Diffusion. London: Oxford Univ. Press; p. 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Rosa E, Urciuolo F, Borselli C, Gerbasio D, Imparato G, Netti PA. Time and space evolution of transport properties in agarose-chondrocyte constructs. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2193–2201. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deen WM. Hindered transport of large molecules in liquid-filled pores. AIChE Journal. 1987;33:1409–1425. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferry JD. Statistical evaluation of sieve constants in ultrafiltration. J Gen Physiol. 1936;20:95–104. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glandt ED. Density distribution of hard-spherical molecules inside small pores of various shapes. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1980;77:512–524. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu WY, Lai WM, Mow VC. A mixture theory for charged-hydrated soft tissues containing multi-electrolytes: passive transport and swelling behaviors. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120:169–180. doi: 10.1115/1.2798299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu WY, Yao H, Vega AL, Flagler D. Diffusivity of ions in agarose gels and intervertebral disc: effect of porosity. Ann Biomed Eng. 2004;32:1710–1717. doi: 10.1007/s10439-004-7823-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffmann EK, I, Lambert H, Pedersen SF. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:193–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holmes MH, V, Mow C. The nonlinear characteristics of soft gels and hydrated connective tissues in ultrafiltration. J Biomech. 1990;23:1145–1156. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johannson L, Löfroth JE. Diffusion and interaction in gels and solutions. IV. Hard sphere Brownian dynamics simulations. J Chem Phys. 1993;98:7471–7479. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson EM, Berk DA, Jain RK, Deen WM. Diffusion and partitioning of proteins in charged agarose gels. Biophys J. 1995;68:1561–1568. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson EM, Berk DA, Jain RK, Deen WM. Hindered diffusion in agarose gels: test of effective medium model. Biophys J. 1996;70:1017–1023. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79645-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson EM, Deen WM. Hydraulic permeability of agarose gels. AIChE Journal. 1996;42:1220–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kedem O, Katchalsky A. Thermodynamic analysis of the permeability of biological membranes to non-electrolytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1958;27:229–246. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90330-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai WM, Hou JS, Mow VC. A triphasic theory for the swelling and deformation behaviors of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1991;113:245–258. doi: 10.1115/1.2894880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai WM, V, Mow C, Roth V. Effects of nonlinear strain-dependent permeability and rate of compression on the stress behavior of articular cartilage. J Biomech Eng. 1981;103:61–66. doi: 10.1115/1.3138261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurent TC, Killander J. A theory of gel filtration and its experimental verification. J Chromatogr. 1964;14:317–330. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurent TC, Sundelof LO, Wik KO, Warmegard B. Diffusion of dextran in concentrated solutions. Eur J Biochem. 1976;68:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazzara MJ, Blankschtein D, Deen WM. Effects of multisolute steric interactions on membrane partition coefficients. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2000;226:112–122. doi: 10.1006/jcis.2000.6800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazzara MJ, Deen WM. Effects of concentration on the partitioning of macromolecule mixtures in agarose gels. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;272:288–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebrun L, Junter GA. Diffusion of sucrose and dextran through agar gel membranes. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1993;15:1057–1062. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(93)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leddy HA, Awad HA, Guilak F. Molecular diffusion in tissue-engineered cartilage constructs: effects of scaffold material, time, and culture conditions. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;70:397–406. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucio AD, Santos RA, Mesquita ON. Measurements and modeling of water transport and osmoregulation in a single kidney cell using optical tweezers and videomicroscopy. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2003;68:041906. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.041906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mackie JS, Meares P. The diffusion of electrolytes in a cation-exchange resin. Theoretical Proc R Soc. 1955;A232:498–509. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauck RL, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Modeling of neutral solute transport in a dynamically loaded porous permeable gel: implications for articular cartilage biosynthesis and tissue engineering. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:602–614. doi: 10.1115/1.1611512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mauck RL, Nicoll SB, Seyhan SL, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. Synergistic action of growth factors and dynamic loading for articular cartilage tissue engineering. Tissue Eng. 2003;9:597–611. doi: 10.1089/107632703768247304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mauck RL, Soltz MA, Wang CC, Wong DD, Chao PH, Valhmu WB, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Functional tissue engineering of articular cartilage through dynamic loading of chondrocyte-seeded agarose gels. J Biomech Eng. 2000;122:252–260. doi: 10.1115/1.429656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mauck RL, Wang CC, Oswald ES, Ateshian GA, Hung CT. The role of cell seeding density and nutrient supply for articular cartilage tissue engineering with deformational loading. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11:879–890. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression: Theory and experiments. J Biomech Eng. 1980;102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishijima Y, Oster G. Diffusion in glycerol-water mixture. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 1960;33:1649–1651. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogston AG. The spaces in a uniform random suspension of fibres. Trans Faraday Soc. 1958;54:1754–1757. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogston AG, Phelps CF. The partition of solutes between buffer solutions and solutions containing hyaluronic acid. Biochem J. 1961;78:827–833. doi: 10.1042/bj0780827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogston AG, Preston BN, Wells JD, Snowden JM. On the transport of compact particles through solutions of chain-polymers. Proc R Soc Lond A. 1973;333:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perry PA, Fitzgerald MA, Gilbert RG. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching as a probe of diffusion in starch systems. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:521–530. doi: 10.1021/bm0507711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Phillips RJ, Deen WM, Brady JF. Hindered transport of spherical macro-molecules in fibrous membranes and gels. AIChE Journal. 1989;35:1761–1769. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pluen A, Netti PA, Jain RK, Berk DA. Diffusion of macromolecules in agarose gels: comparison of linear and globular configurations. Biophys J. 1999;77:542–552. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quinn T, Kocian P, Meister J. Static compression is associated with decreased diffusivity of dextrans in cartilage explants. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:327–334. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sah RL, Kim YJ, Doong JY, Grodzinsky AJ, Plaas AH, Sandy JD. Biosynthetic response of cartilage explants to dynamic compression. J Orthop Res. 1989;7:619–636. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Satterfield CN, Colton CK, Turckheim B, Copeland TM. Effect of concentration on partitioning of polystyrene within finely porous glass. AIChE J. 1978;24:937–940. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shao J, Baltus RE. Effect of solute concentration on hindered diffusion is porous membranes. AIChE J. 2000;46:1307–1316. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith FG, III, Deen WM. Electrostatic double-layer interactions for spherical colloids in cylindrical pores. J Colloid Interf Sci. 1980;78:444–465. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sofou S, Thomas JL. Stable adhesion of phospholipid vesicles to modified gold surfaces. Biosens Bioelectron. 2003;18:445–455. doi: 10.1016/s0956-5663(02)00153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tong J, Anderson JL. Partitioning and diffusion of proteins and linear polymers in polyacrylamide gels. Biophys J. 1996;70:1505–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79712-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Travascio F, Zhao W, Gu WY. Characterization of anisotropic diffusion tensor of solute in tissue by video-FRAP imaging technique. Ann Biomed Eng. 2009;37:813–823. doi: 10.1007/s10439-009-9655-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Truesdell C, Toupin R. The classical field theories. Heidelberg: Springer; p. 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu X, Cui Z, Urban JP. Measurement of the chondrocyte membrane permeability to Me2SO, glycerol and 1,2-propanediol. Med Eng Phys. 2003;25:573–579. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(03)00073-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]