Abstract

Approaches to research in organic chemistry are as numerous as the reactions they describe. In this account, we describe our reactivity-based approach. Using our work in the area of gold-catalysis as a background, we discuss how a focus on reaction mechanism and reactivity paradigms can lead to the rapid discovery of new synthetic tools.

Keywords: gold catalysis, enantioselective catalysis, cycloisomerization, alkynes, allenes

1 Introduction

“Our scientific theories do not, as a rule, spring full-armed from the brow of their creator. They are subject to slow and gradual growth…”

– Professor Gilbert N. Lewis writing in Science in 1901.1

At the time Lewis was speaking of ionic theory, but his words resonate throughout chemistry. To an organic chemist, his words speak to the difficulty associated with the prediction of reactivity. In answer to this challenge, numerous approaches to chemical research have been devised. We have categorized these research styles into the four methods that we perceive to be most prevalent (Table 1).

Table 1.

Approaches to methodology research in organic chemistry.

| Approach | Hypothesis |

|---|---|

| Motif-based | New methods for the synthesis of a specific chemical motif are needed. |

| Bond-based | The transformation of one specific set of chemical bonds into another would be a useful synthetic transformation. |

| High-throughput screening (HTS) | HTS of reaction conditions will lead to the discovery of new reactions. |

| Reactivity-based | Understanding and expanding reactivity paradigms will lead to the discovery of new reactions. |

Historically, chemists have been motivated by problems in total synthesis or by a desire to develop reactions of broad utility. With total synthesis of natural or unnatural compounds as the driving force, methods development is typically focused on the efficient synthesis of a certain chemical motif (Table 1).2 In contrast, bond-based methodology programs focus on transformations of specific chemical bonds.3 A third approach employs high-throughput screening to identify reaction conditions that will allow a more general type of transformation.4 We have undertaken an alternative approach, one that we describe as reactivity-based. Instead of focusing on specific reactions, we concentrate our efforts on understanding and expanding specific reactivity paradigms.5

We do not argue that one of the approaches to reaction discovery described above is superior to the others. On the contrary, we would claim that each approach is important in and of itself, and that each complements the next. Nonetheless, this account will highlight our reactivity-based approach, using gold catalysis as a backdrop for this discussion.

We typically begin our research with a fragment of theoretical knowledge, commonly a proposed reaction mechanism or intermediate. Initially, this background was derived from the literature; although, as our research program has developed, we have frequently been able to utilize our own proposed mechanisms. From this theoretical knowledge we seek to extract a hypothesis that can be subsequently tested in the laboratory. After designing and executing the appropriate test, conclusions are drawn that can either contradict, support, or expand the initial theory. While it is not always the case, progress through this cycle frequently results in the discovery of new reactivity paradigms.

2 Addition reactions

2.1 The Conia-Ene Reaction

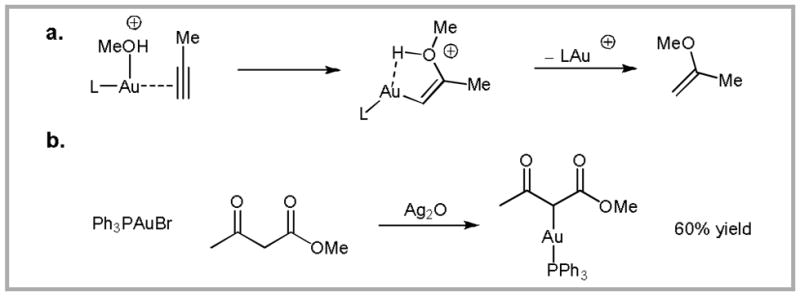

We were initially attracted to the area of gold-catalysis by the pioneering report of Teles and coworkers showing that cationic gold(I) complexes can activate alkynes towards nucleophilic attack by alcohol nucleophiles.6 Based on a series of calculations, Teles proposed a cis-addition mechanism, in which the gold(I) catalyst is coordinated to both the alcohol and the alkyne (Scheme 1a). A subsequent survey of the literature led us to a report from 1974 describing the stoichiometric auration of β-ketoesters (Scheme 1b).7 Combining this report with Teles’ mechanistic hypothesis led to the simple hypothesis that gold(I) complexes might be employed as catalysts for the addition of β-ketoesters to alkynes.

Scheme 1.

(a) The mechanism, which has subsequently been disproved, originally proposed by Teles and coworkers for the addition of alcohols to alkynes mediated by Au(I) complexes. (b) A reaction reported in 1974 showing the carboauration of β-ketoesters. These reports prompted us to investigate the Au-catalyzed addition of β-ketoesters to alkynes.

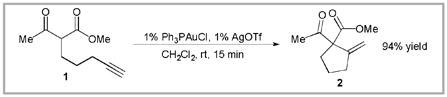

To test this hypothesis, we designed a simple substrate (1) containing a β-ketoestertethered alkyne (Equation 1).8 To our delight, Ph3PAu+•TfO− (formed in situ from Ph3PAuCl and AgOTf) catalyzed the desired C-C bond forming event rapidly at room temperature. Thus, by testing a simple hypothesis we had discovered a mild method for affecting C-C bond formation.9,10 Furthermore, we were able to contribute to the database of knowledge surrounding gold-catalysis.11

|

Equation 1 |

This discovery also allowed us to postulate additional hypotheses. One of the simplest was that this reaction should be applicable to internal alkynes. To our surprise, these substrates were mostly unreactive even under more forcing conditions. This contradiction to our hypothesis, prompted us to test the validity of the cis-addition mechanism that had been proposed by Teles.

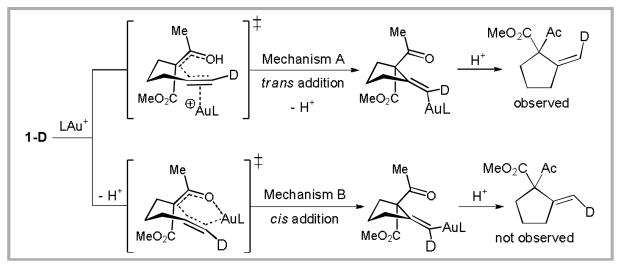

When deuterium-labeled alkyne 1-D was subjected to the reaction conditions, the deuterium was selectively incorporated syn to the ketoester (Scheme 2). This result supports a mechanism involving trans addition of the ketoester to a pendant Au-activated alkyne.12 Furthermore, this mechanism also provides an explanation for the poor reactivity of internal alkynes, which would experience severe 1,3-allylic strain in the cyclization transition state. Further support for this mechanism, including the isolation and characterization of related vinyl-gold intermediates, has accumulated.13

Scheme 2.

Mechanistic proposals in the gold(I)-catalyzed Conia-ene reaction. Experimental results support a mechanism involving trans addition.

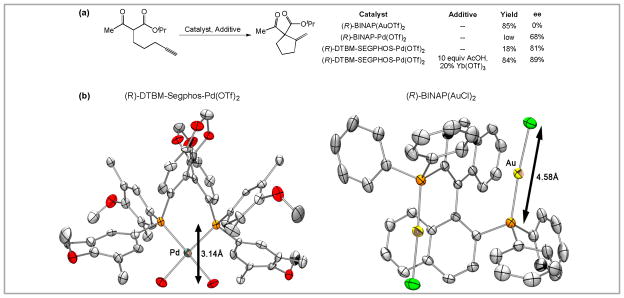

Our initial attempts to render this reaction enantioselective were frustrated by the consequences of a trans-addition mechanism. Employing chiral phosphinegold(I) complexes in the Conia-ene reaction induced very little enantioselectivity (Scheme 3a). This is not too surprising; gold(I) complexes typically adopt a two coordinate, linear geometry, which places the prochiral nucleophile more than 5A from the chiral phosphine in the cyclization transition state. This can be seen in x-ray crystal structure of (R)-BINAP(AuCl)2 (Scheme 3b), where the distance between the phosphine and the chloride ligands is 4.58 A. In the catalytic reaction, the alkyne of the substrate would replace the chloride, and the prochiral ketoester would approach the alkyne from a position trans to gold (as in Scheme 2, mechanism A).

Scheme 3.

Transition metal catalyzed enantioselective Conia-ene reaction. (a) Effect of transition metal and ligand on enantioselectivity. (b) A comparison of (R)-DTBM-SEGPHOS-Pd(OTf)2 and (R)-BINAP(AuCl)2 complexes showing the effect of metal geometry on the proximity of the ligand and substrate. (tert-butyl groups and OTf counteranions in the Pd complex have been removed for clarity).

In order to render the Conia-ene reaction enantioselective, we surveyed other π-acidic metal complexes that are not confined to a linear geometry. While chiral Cu(II), Ni(II), and Pt(II) complexes gave poor selectivity, we were satisfied to find that the square planar BINAP-Pd(OTf)2 complex provided the desired product with moderate enantiomeric excess (68% ee), albeit in low yield (Scheme 3a). Further investigation revealed that the yield could be increased through the addition of Brønsted and Lewis acids14, while the enantioselectivity was improved by replacing (R)-BINAP with (R)-DTBM-SEGPHOS (89% ee). For comparison, the X-ray crystal structure of (R)-DTBM-SEGPHOS-Pd(OTf)2 is illustrated in Scheme 3b. In this case, the distance between phosphine and substrate-binding sites is decreased to 3.14 A (versus 4.58 A for the Au(I) catalyst). We subsequently applied the principles we had learned in developing the Au(I)- and Pd(II)-catalyzed Conia-ene reactions to include transformations employing silyl enol ethers as nucleophiles.15 This methodology was subsequently applied to total synthesis of (+)-lycopladine A and (+)- fawcettimine.16

2.2 Asymmetric Hydroamination

Despite our success using Pd(II)-catalysts to render the Conia-ene reaction enantioselective, we soon returned to the challenge of asymmetric gold catalysis. We quickly realized that the requirement for a prochiral nucleophile in enantioselective additions to alkynes greatly limits the scope of possible transformations. To overcome this problem, we have subsequently employed a number of strategies.

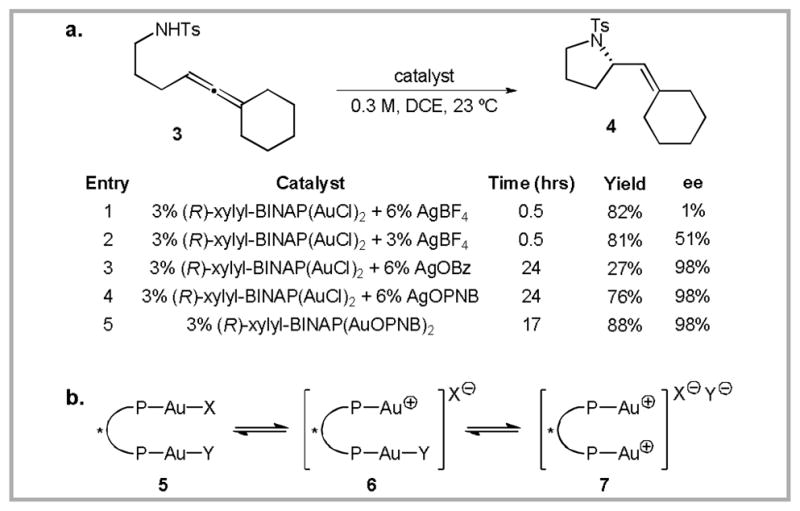

The first of these strategies involved gold-catalyzed addition of various nucleophiles to achiral allenes (which are prochiral electrophiles).17 In the hydroamination of allene 3, we were initially frustrated by variable enantioselectivities (1–51% ee) when (R)-xylyl-BINAP(AuCl)2 was employed as the precatalyst (Scheme 4a).18 After some experimentation, we found that the amount of AgBF4 was crucial in determining the enantioselectivity of the transformation, with lower equivalents of Ag relative to Au providing higher ee. This suggested that the mono-cationic species 6 was providing enantioenriched product, while the dicationic species 7 was providing the product with lower enantiocontrol (Scheme 4b). 31P-NMR of a solution containing a 2:1 mixture of (R)-xylyl-BINAP(AuCl)2 and AgBF4 revealed that all three species 5-7 are present. By replacing the non-coordinating tetrafluoroborate counteranion with a more coordinating benzoate anion (OBz), we were able to shift the equilibrium towards 5 and 6, resulting in a large increase in enantioselectivity (98% ee, Scheme 4i, entry 3). Ultimately, the benzoate anion proved to be too coordinating, providing only low yields of the product even after extended reaction times. Fortunately, reactivity could be increased, without any decrease in selectivity, by switching to the p-nitrobenzoate (OPNB) counteranion (entry 4). The resulting gold-OPNB complexes proved to be bench-stable white solids, the use of which further improved the yield of the reaction (entry 5).

Scheme 4.

(a) Development of a gold(I)-catalyzed asymmetric hydroamination reaction. (b) A possible rationale for the observed counteranion effects.

2.3 Chiral Counteranions

We initially hypothesized that gold(I) benzoates provide increased enantioselectivity in the formation of 4 by preventing the formation of the dicationic complex 7 and also by increasing the size of the remaining coordinated anion in the active catalyst (Y in 6). Another possible explanation is that the counteranion (X in 6) influences the relative rate of cyclization of the diastereomeric gold(I)-coordinated allene complexes. We predicted that if this were true, it should also be the case that chiral counteranions should be able to influence the relative rate of cyclization onto enantiomeric gold(I)-coordinated allene complexes.19 To test this third hypothesis, we prepared a set of chiral silver phosphates.

Treatment of dppm(AuCl)2, an achiral gold(I) complex, with silver phosphate 8 provided a complex, which catalyzed the enantioselective hydroalkoxylation of allene 9 (Scheme 5).20 Further optimization revealed that less polar solvents provided higher enantioselectivity, a result which is consistent with an ion-pair model for enantioinduction. This result is particularly remarkable in light of the fact that we were never able to achieve even moderate enantioselectivities for this transformation when chiral phosphines were employed. We have subsequently expanded the scope of these transformations to include both N- and O-linked hydroxylamine nucleophiles.21 As a group, these reactions provide access to a diverse range of enantioenriched heterocycles, including pyrazolidines, isoxazolidines, tetrahydrooxazines, tetrahydrofurans, tetrahydropyrans, pyrrolidines, and butyrolactones.

Scheme 5.

The first report of a highly enantioselective, chiral counteranion-controlled asymmetric reaction.

As an approach to asymmetric transition-metal catalysis, the use of chiral counteranions is complementary to the use of chiral ligands.22,23 It therefore has the potential to significantly expand the scope of reactions that can be rendered asymmetric.

2.4 Exploiting Basic Counteranions

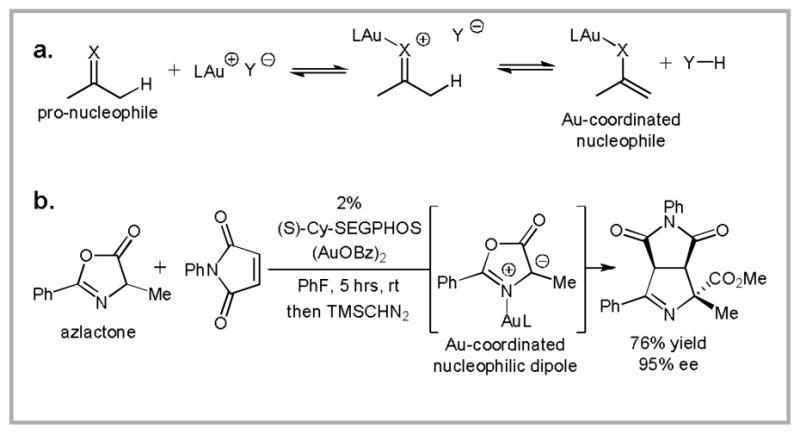

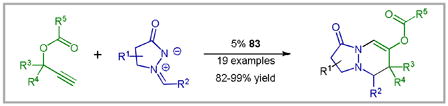

The observation that the reactivity of cationic gold(I)-complexes can be modulated through the basicity of the counteranion prompted us to investigate the potential of these catalysts to activate pronucleophiles. In this scenario, more basic counteranions should favor the formation of the Au-coordinated nucleophile and the conjugate acid of the counteranion (Scheme 6a).24 We employed this strategy to activate azlactones for cycloaddition with electron deficient olefins (Scheme 6b).25 Employing (S)-Cy-SEGPHOS(AuOBz)2 as the catalyst, this reaction provides an attractive route to enantioenriched proline derivatives.26

Scheme 6.

(a) A potential mechanism for pro-nucleophile activation by Au (I). (b) Au(I)-catalyzed enantioselective 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition initiated by formation of a Au-coordinated Münchnone.

2.5 Ring Expansion Reactions

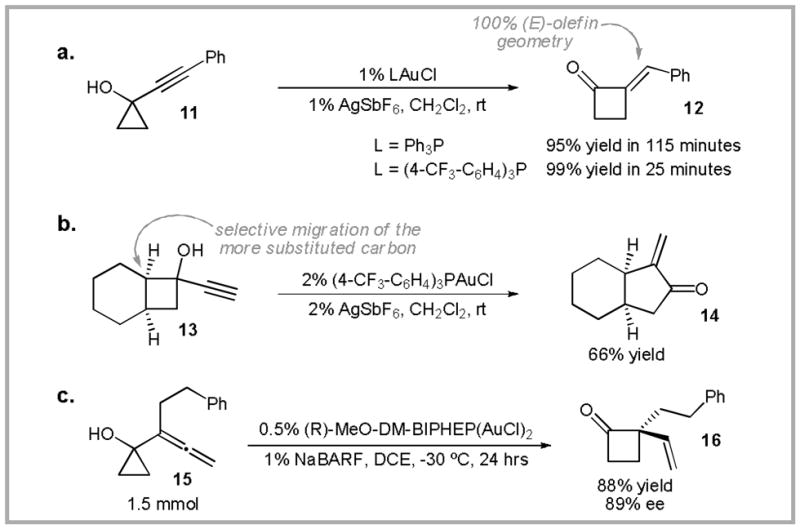

In the addition reactions described above, Au(I)-coordination to a C-C unsaturation is proposed to induce trans addition of a tethered nucleophile. This stands in contrast to nucleophile-activation-based mechanisms that have been proposed for early transition-metals, lanthanides, and actinides.27 Based on this precedence, we hypothesized that Au(I) should also catalyze the addition of nucleophiles that lack metal-coordination sites (i.e. a C-C σ-bond). Thus, treatment of alkynylcyclopropanol 11 with 1% of a cationic phosphine-Au(I) complex provided cyclobutanone 12 as a single olefin isomer (Scheme 7a).28 Higher yields and shorter reaction times were obtained with when electron-deficient arylphosphines were employed as ligands.29 Alkynyl cyclobutanols, such as 13, were also found to be viable substrates for gold(I)-catalyzed ring expansion (Scheme 7b). The formation of the (E)-olefin and the selective migration of the more substituted cycloalkanol carbons is consistent with a mechanism in which coordination of the gold(I) catalyst to the alkyne induces a 1,2-alkyl shift.30,31 A vinylogous variant of this reaction was applied to the total synthesis of ventricosene.32

Scheme 7.

Au(I)-catalyzed cyclopropanol ring expansion reactions.

Ring-expansion of allenylcyclopropanols (i.e. 15) provides access to cyclobutanones possessing a vinyl-substituted quaternary center. This reaction could be rendered enantioselective by employing (R)-MeO-DM-BIPHEP as the ancillary ligand (Scheme 7c).33,34

2.6 Intramolecular carboalkoxylation

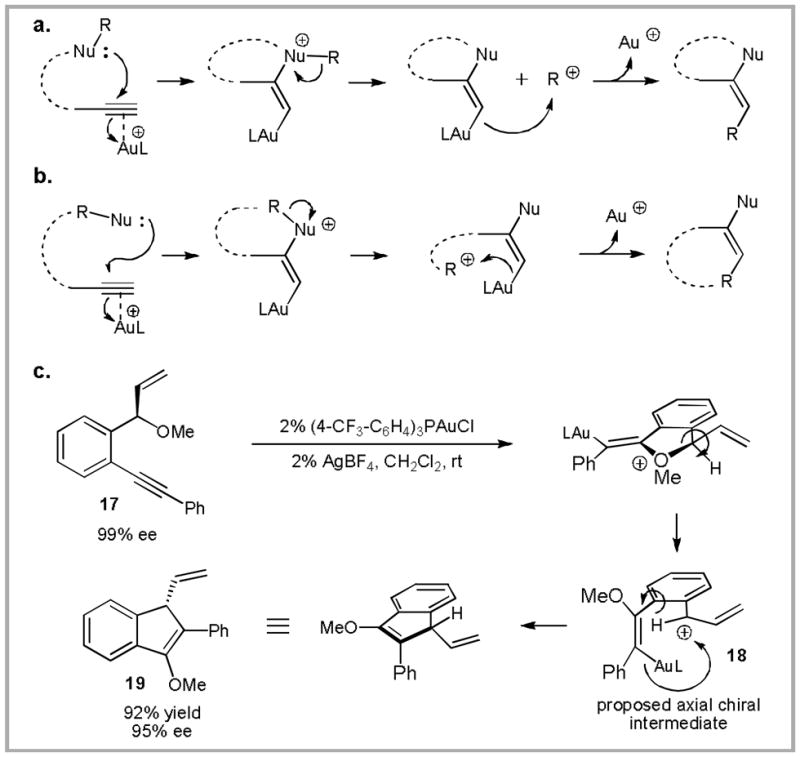

The research described in the previous sections illustrates that gold(I)-mediated electrophilic activation of C-C multiple-bonds provides an opportunity for mild C-C and C-X bond formation. In addition, through scrupulous choice of chiral ligand and/or chiral counteranion, many of these reactions can be rendered enantioselective. Nevertheless, these reactions fall under the reactivity paradigm encompassed by Markovnikov’s rule.35 An important expansion beyond these transformations would be to trap the proposed vinyl gold intermediates with electrophiles other than a proton. This would allow for the formation of additional bonds and the rapid generation of molecular complexity. Towards this goal, we envisioned that protonation of the vinyl gold intermediate could be avoided via in situ generation of an alternate electrophile. Thus, addition of a neutral, aprotic nucleophile to a gold-coordinated alkyne leads to an increase in positive charge on the nucleophile (Scheme 8a, 8b). Fragmentation of a single bond attached to this nucleophile generates a reactive electrophile (R+), which can be trapped by the vinyl-Au moiety.36

Scheme 8.

(a) and (b) Mechanistic possibilities for the in situ generation of reactive electrophiles and subsequent trapping of vinyl Au moieties. (c) Application to the synthesis of enantioenriched indenyl ethers.

Towards this end, treatment of methoxy ether 17 with a cationic gold(I) catalyst generates carboalkoxylation product 19 (Scheme 8c).37 The surprising observation that the chirality in the starting material is transferred to the product with inversion lead us to propose the mechanism outlined in Scheme 8c. Following addition of the methoxy moiety to the Au(I)-coordinated alkyne, fragmentation of the C-O bond is expected to occur in such a way that maximizes overlap of the developing p-orbital with the aromatic π-system. By also minimizing steric interactions of the benzylic substituent (vinyl in this case) with the developing enol ether, the axial chiral intermediate 18 is formed. Subsequent trapping of the carbocation by the vinyl Au must be faster than racemization in order to maintain efficient chirality transfer.38

2.7 Rationalizing the π-Acidity of Cationic Gold(I) Complexes

The Au(I)-catalyzed Conia-ene reaction of β-ketoester 1 provides cyclopentane 2 in 15 minutes in 94% yield with only 1% catalyst loading (Section 2.1). In contrast, the AgOTf-catalyzed reaction requires 10% catalyst loading and proceeds to only 50% conversion after 18 hours.39 Furthermore, while an ancillary phosphine accelerates the Au-catalyzed reaction, the addition of triphenylphosphine to the AgOTf-catalyzed reaction eliminates all catalytic activity. In order to further understand these differences, we considered a prototypical catalytic cycle for the addition of a protic nucleophile to an alkyne (Scheme 9). In doing this, we made the assumption that coordination of the cationic Au(I)-catalyst to the alkyne is reversible and that nucleophilic addition is therefore rate determining. Thus, we reasoned that further study of Au(I)-coordinated π-bonds would lead to a better understanding of Au(I)-catalysis.40

Scheme 9.

A typical catalytic cycle for the Au(I)-catalyzed addition of protic nucleophiles to alkynes.

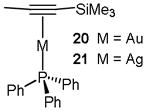

We noted that there was minimal literature prescence for the isolation and characterization of cationic phosphine Au(I)-π-complexes. We hypothesized that these difficultites might be overcome by tethering a coordinatively stable phosphine ligand to the more labile alkyne.41 Using this strategy, we were able to obtain x-ray quality crystals of analogous cationic Au(I) and Ag(I)-coordinated alkynes. These structures allowed a comparitive analysis, which was further augmented with DFT calculations. Second-order pertubative analysis revealed that σ-donation from the alkyne π-bond to the metal center is the most important bonding interaction for both Au and Ag (Table 2).42 However, the magnitude of this interaction is significantly larger for Au (56.6 kcal/mol versus 38.5 kcal/mol for Ag). This interaction is primarily responsible for augmenting the electrophilicity of the coordinated alkyne. Interestingly, back-donation from Au to the π* of the coordinated alkyne is also larger in magnitude (13.3 kcal/mol versus 6.4 kcal/mol for Ag). While this interaction is expected to decrease the electrophilicity of the coordinated alkyne, it suggests that back-donation from Au may be important for other aspects of Au(I)-catalysis, as described below.

Table 2.

Natural Bond Order Orbital Interaction Energies (kcal/mol)

| Parameter | 20 (M = Au) | 21 (M = Ag) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| π → M | 56.6 | 38.5 |  |

| M → π* | 13.3 | 6.4 | |

| Difference | 43.3 | 32.1 |

3 Reactions Involving Carbenoid Intermediates

A reactivity-based approach to organic synthesis requires that reaction mechanisms are constantly proposed and tested. As described throughout section 2, even in our forays in enantioselective catalysis, the testing of mechanistic proposals has frequently produced the most important advances. This testing process plays an even more pivotal role in the development of new, mechanistically distinct, reactions. In this section, we describe a series of reactions that are linked by a stream of mechanistic proposals.

3.1 1,5-Enyne Cycloisomerization

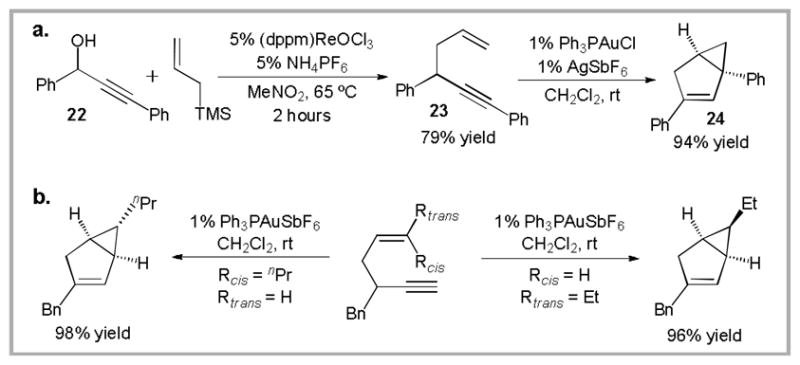

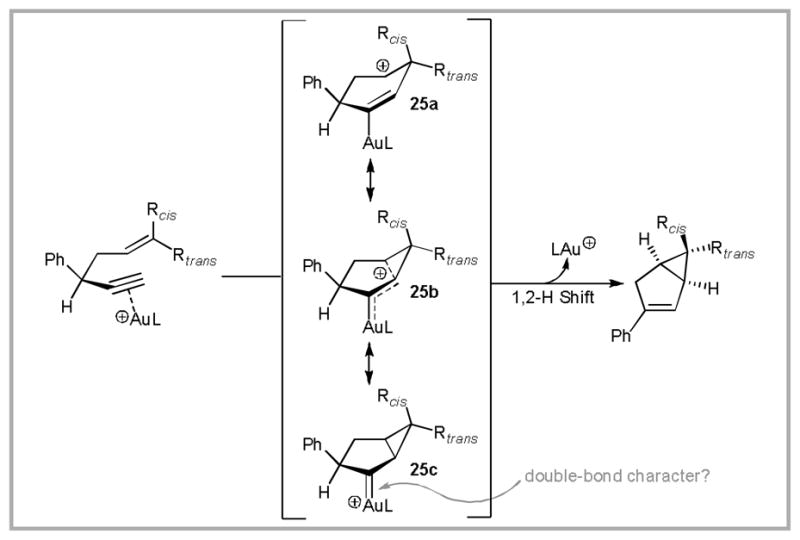

Following our success with the Au(I)-catalyzed Conia-ene reaction we decided to explore the intramolecular addition of less-activated carbon nucleophiles to alkynes. A simple mono-substituted olefin constitutes the simplest of these nucleophiles. Coincidentally, we had recently developed a Re-catalyzed synthesis of 1,5-enynes from propargyl alcohols.43 Thus, treatment of propargyl alcohol 22 with allylsilane and catalytic (dppm)ReOCl3 produced 1,5-enyne 23 in 79% yield (Scheme 10a). Subsequent gold(I)-catalyzed cycloisomerization affected clean conversion to bicyclo[3.1.0]hexene 24.44,45,46

Scheme 10.

(a). Re-catalyzed synthesis of 1,5-enynes and subsequent Au-catalyzed cycloisomerization. (b) Stereospecific cycloisomerizations.

The formation of 24 suggested a new mode of reactivity in gold catalysis. This prompted us to further investigate the reaction mechanism. As illustrated in Scheme 10b, Reaction of substrates containing 1,2-disubstituted olefins proceeded stereospecifically. We also found that a propargyl deuterium label is selectively incorporated in the vinyl position of the product. On the basis of these observations, we proposed the mechanism that is partially illustrated in Scheme 11. Initial coordination of the alkyne by the cationic gold(I) catalyst induces cyclization of the pendant olefin, producing cationic intermediate 25. The electronic structure of this intermediate can be represented by a number of resonance forms ranging from carbocation 25a to gold carbenoid 25c. The degree of bonding from gold to carbon will be further discussed in section 3.5. A 1,2-hydrogen shift produces the desired product and liberates the gold catalyst.

Scheme 11.

Proposed 1,5-enyne cycloisomerization mechanism.

3.2 Intramolecular Addition of Dipolar Nucleophiles to Alkynes

The postulate that gold can stabilize the positive charge in 25 was initially the matter of some debate. Nevertheless, the concept that gold can act as both a π-acid and as an electron donor has been useful in predicting new reactivity. We hypothesized that we could exploit this behavior in the gold-catalyzed addition of ylide-like nucleophiles to alkynes (Scheme 12).

Scheme 12.

A few possible routes to gold-carbenoids from ylide-tethered alkynes. Nu = nucleophile, LG = leaving group.

For example, following gold-catalyzed nucleophilic addition of the azide in 26 to the pendant alkyne, back-donation from gold is sufficient to affect the loss of dinitrogen (Scheme 13).47 The resulting intermediate (27) is similar to 25 in appearance and again raises questions as to the nature of the Au-C bond in these types of intermediates. The observed pyrrole product 28 is produced following a 1,2-hydrogen migration and subsequent tautomerization.

Scheme 13.

Gold(I)-catalyzed intramolecular acetylenic Schmidt reaction.

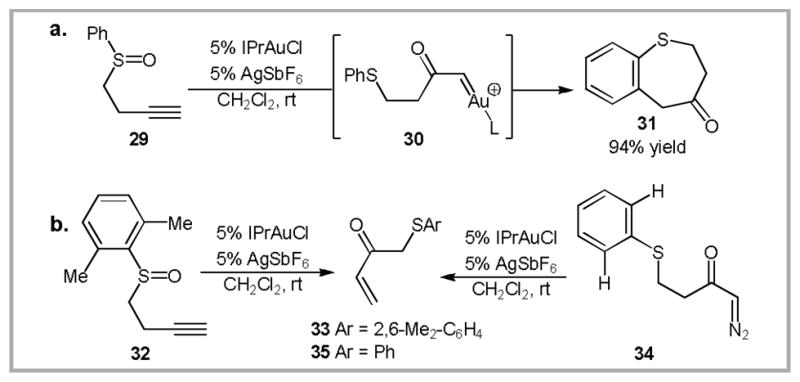

This concept was further expanded in the reaction of alkynyl sulfoxides (Scheme 14).48 Gold(I)-catalyzed rearrangement of 29 provides an alternative route to a carbenoid intermediate (30) that would traditionally be accessed via transition metal catalyzed decomposition of α-diazocarbonyl compounds.49,50 In this particular case, the proposed carbenoid intermediate undergoes a formal intramolecular C-H insertion to provide benzothiepinone 31. An internal competition inverse kinetic isotope effect suggests that the formal C-H insertion proceeds via a Friedel-Crafts type mechanism. When the ortho-positions of the aromatic ring are blocked (as in 32), sluggish conversion to enone 33 is observed. Surprisingly, when S-phenyl, α-diazoketone 34 is subjected to the same reaction conditions, enone 35 is produced instead of benzothiepinone 31. This suggests that the gold-catalyzed rearrangement of alkynyl sulfoxides provides a route to intermediates that are actually inaccessible from the corresponding α-diazocarbonyl compounds. An explanation of this divergent reactivity remains an area for future exploration.

Scheme 14.

Gold(I)-catalyzed sulfoxide rearrangements.

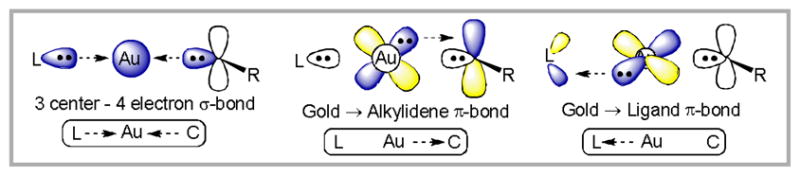

In 1984, Rautenstrauch reported the palladium(II) catalyzed isomerization of propargyl acetates 35 to cyclopentenones 37 (Scheme 15a).51 This reaction is proposed to proceed via Pd-carbenoid 36. Based on the similarity of this reaction mechanism to those discussed above, we postulated that propargyl ester rearrangement could provide a third route to gold-carbenoid intermediates. To our delight, gold(I)-catalysis allowed the substrate scope of this transformation to be significantly expanded.52 In order to confirm the proposed reaction mechanism, we subjected enantioenriched propargyl ester 38 to our gold-catalysis conditions (Scheme 15b). To our surprise, we observed excellent chirality transfer. This suggests that an achiral gold-carbenoid intermediate is not present in the catalytic cycle. As an alternative mechanistic proposal, we suggested that a cyclic transition state (39) would account for chirality transfer. Subsequent calculations supported a similar hypothesis, in which a helical intermediate allows for efficient chirality transfer.53 However, as will be discussed below, these results do not imply that carbene-like behavior cannot be accessed from propargyl esters.

Scheme 15.

(a) Pd-catalyzed Rautenstrauch rearrangement. (b) The gold-catalyzed variant allows for efficient chirality transfer. In order to account for this observation, we proposed a cyclic transition state. Calculations later showed that the C-O breaking and C-C bond forming events occur separately, while the chirality is retained in a helically chiral intermediate.

3.3 Stereospecific Cyclopropanation

The term ‘carbenoid’ is defined as a “description of intermediates which exhibit reactions qualitatively similar to those of carbenes without necessarily being free divalent carbon species.”54 Therefore, in order for carbenoid to be apt descriptor of gold-stabilized cationic intermediates, such as 25, these intermediates must exhibit reactivity that is similar to that of a free carbene.

Of the reactions that typify free singlet carbenes, the stereospecific cyclopropanation of olefins is one of the most indicative.55 We therefore sought to test the ability of the proposed gold-carbenoid intermediates to cyclopropanate olefins.50,56 For this task we employed propargyl esters, which had been previously reported to be convenient precursors to carbenoid intermediates.57 Accordingly, we found that cyclopropanation of cis- and trans-β-methyl styrenes with propargyl ester 41 occurs stereospecifically in the presence of a catalytic amount of a gold(I) catalyst (Scheme 16a). In addition, and in contrast to the Rautenstrauch rearrangements discussed above, we found that chirality was not transferred from enantioenriched propargyl esters to the cyclopropane products.

Scheme 16.

(a) Demonstrating that Au(I)-catalyzed cyclopropanation is stereospecific. (b) An enantioselective variant.

Encouraged by these results, we sought to develop an enantioselective variant of this reaction. Successful transmission of chiral information from the ancillary ligand on gold to the cyclopropane product would provide further evidence for the participation of the gold catalyst in the cyclopropanation step. In the event, (R)-DTBM-SEGPHOS(AuCl)2 catalyzed the asymmetric cyclopropanation of styrene to provide the product with 81% ee (Scheme 16b).58 This concept was subsequently applied to the asymmetric synthesis of 7- and 8-membered rings via intramolecular Au(I)-catalyzed cyclopropanation.59

3.4 Au-C Bonding in Cationic Intermediates and Relativistic Effects

We were initially hesitant to define the exact nature of bonding between gold and carbon in intermediate 25. We wrote: “cyclopropylcarbinyl cation [25b] may have some gold(I)-carbene character ([25c]). The bicyclo[3.1.0] hexene product is generated by a 1,2-hydrogen shift onto a cation or gold(I) carbene.” Even the boldness of this statement was based on literature precedence.60 However, as evidence for gold-carbenoid reactivity accumulated (vide supra), we sought to provide a theoretical explanation for this behavior.

Previous experimental and theoretical reports61 suggested that gold carbenoid behavior is indeed plausible and can be ascribed to the relativistic expansion of the 5d-orbitals on Au (Figure 1).62 This expansion allows delocalization of the electrons in these orbitals into carbon-based orbitals of sufficiently low energy (in particular an unoccupied p-orbital of a carbocation). This provides an explanation for why Au-carbenes display behavior that is reminiscent of the reactivity of other transitional metal carbene complexes. On the other hand, the relativistic contraction of the 6s-orbital provides an explanation for the increased π-acidity of gold, as this orbital is the primary acceptor of electron-density from ligands and substrates.63 Thus, cationic gold complexes are typically stronger π-acids when compared to Ag and Cu, yet also retain the ability to stabilize adjacent carbocations via back-donation.

Figure 1.

A comparison of calculated sizes and energies of Au 6s and 5d orbitals with and without consideration of relativistic effects.62

3.5 A Bonding Model for Au(I)-Carbene Complexes

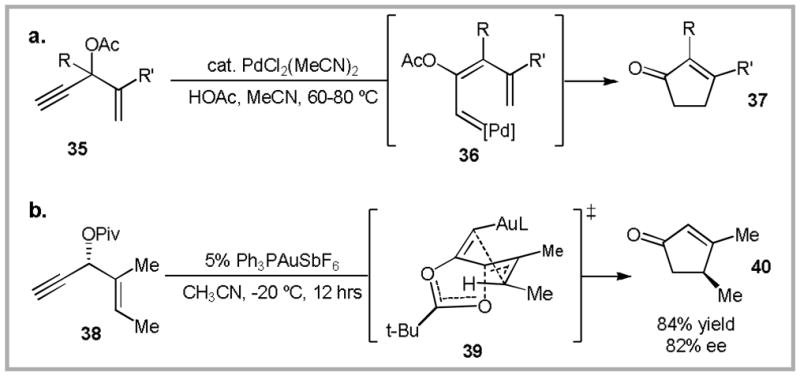

Consideration of relativistic effects allows carbenoid reactivity in Au-catalysis to be rationalized; however, we postulated that a more specific description of the bonding in Au-carbene complexes would allow improved prediction and explanation of reactivity.64 With this in mind, in collaboration with the Goddard group, density functional theory calculations were used to determine the effect of both carbene substituents (R, R′) and the ancillary ligand (L) on bonding in Au-carbene complexes 42. In agreement with previous calculations, we found that the Au-C bond in complexes 43-45 is composed mainly of π-type bonding (Figure 2).65 Furthermore, the degree of π-back donation from Au to the carbene is largely dictated by the carbene substituents. For example, π-bonding between Au and the carbene fragment is decreased relative to σ-bonding in 45, a species which is stabilized by two oxygen-atoms.

Figure 2.

Calculated bond-distances and relative natural orbital populations for three cationic Au(I)-carbene complexes.

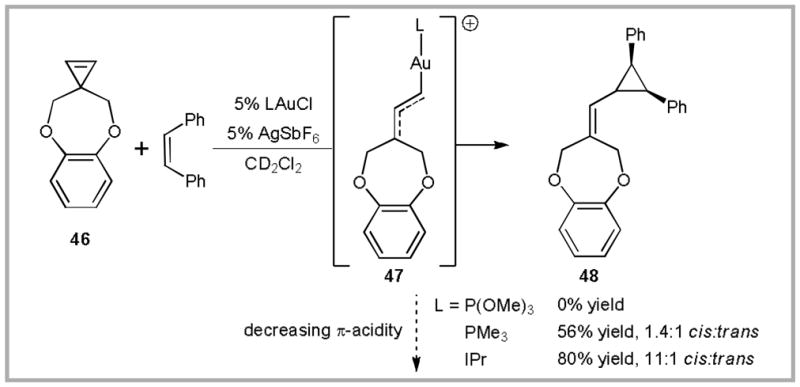

The ligand-Au-carbene bonding triad can be divided into three components (Figure 3). The σ-bonding is mainly composed of a 3 center – 4 electron hyperbond66 (where hyperbond refers to bonding beyond the reduced 12-electron valence space and can be represented by the resonance forms: L:Au-C ↔ P-Au:C). As a result, strongly σ-donating ligands decrease the Au-C bond order (trans influence). The π-bonding is comprised of electron donation of two orthogonal d-orbitals on Au into π-acceptor orbitals on the ligand and the carbene. These two π-bonds compete for electron density and therefore have an indirect effect on each other. Overall, this bonding model suggests that formation of a Au-carbene complex from a vinyl Au-intermediate occurs with an increase in Au → C π-bonding and a decrease in C → Au σ-bonding. Thus, the depiction of a gold-carbon double bond should be understood to mean that both π and σ components to the bond are present, but not that the Au-C bond has a bond order of two.67 Indeed, the calculated natural bond orders for 43 (1.14), 44 (0.91), and 45 (0.53) are all significantly less than two.

Figure 3.

A bonding-model for Au-carbene complexes.

This bonding model can be used to predict the effect of ancillary ligands on reactivity.29 Strongly σ-donating ligands increase the Au-C bond length, thereby increasing ‘free-carbene’ like behavior. In contrast, π-acidic ligands are expected to decrease σ-donation from Au to carbene, thereby increasing carbocation-type reactivity. As a result, carbene-like reactivity is favored for ancillary ligands that are π-donating or π-neutral and strongly σ-donating. This trend is demonstrated in the yield of cyclopropanation product 48 obtained from Au-catalyzed decomposition of cyclopropene 46 (Scheme 17). This reaction is expected to proceed via a Au-carbene intermediate (47) that is similar to 44. The highest yield was obtained when the N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) ligand IPr (1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropyl-phenyl)imidazol-2-ylidene) was employed (NHC ligands are strongly σ-donating and only weakly π-acidic). In contrast, trimethylphosphite, a strongly π-acidic ligand, provided none of the desired product.

Scheme 17.

The effect of the ancillary ligand (L) on the reactivity of Au(I)-carbene complexes.

4 Further Insights into Reactivity from Au-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization Reactions

4.1 Intramolecular Rearrangements of 1,5-Enynes

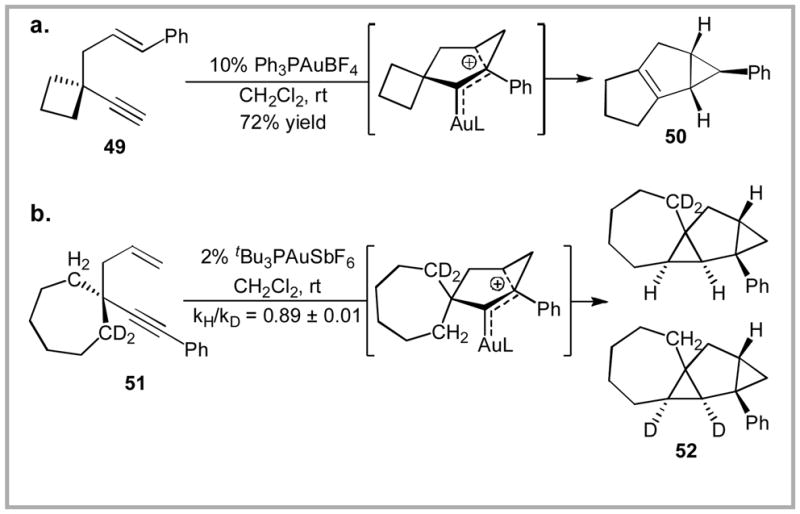

In the absence of an available hydrogen for a 1,2-hydride shift, a given gold carbenoid intermediate can undergo several other types of rearrangement. For example, a gold-carbene intermediate related to 25 will also undergo an intramolecular 1,2-alkyl shift/ring-expansion to produce tricycle 50 (Scheme 18a).44 Interestingly, gold-catalyzed cycloisomerization of the related enyne 51 produces tetracycle 52 via an intramolecular C-H bond insertion (Scheme 18b).68 In this case, we hypothesize that the adjacent 7-membered ring allows the adjacent C-H bonds to adopt an optimal position for insertion.69,70

Scheme 18.

Observed products resulting from intramolecular rearrangement of cationic intermediates.

We performed several kinetic isotope effect experiments in order to gain further insight into the mechanism of this C-H insertion. The results suggest that a mechanism involving simple hydride transfer to the carbenoid intermediate is unlikely.71

4.2 Ligand- and Substrate-Controlled Access to [2 + 2], [3 + 2], [4 + 2], and [4 + 3] Cyclo-additions in Au-Catalyzed Reactions of Allene-Enes

We had developed a number of reactions suggesting that Au-containing cationic intermediates of type 42 can display either carbene-like or carbocation like reactivity. In order to further understand this divergence in reactivity, we sought to quantify the degree of carbocation stabilization in Au(I)-carbene complexes.

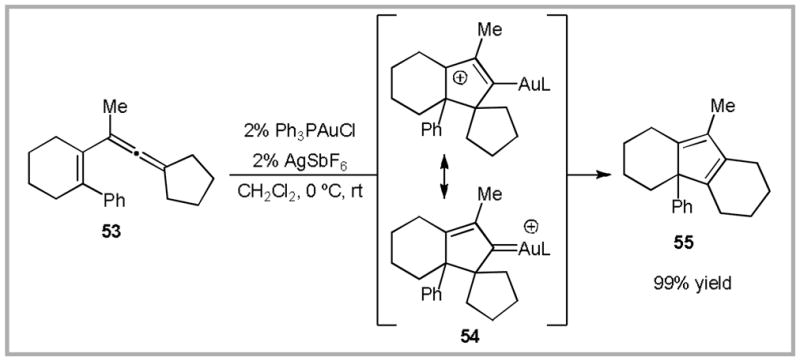

To identify a platform for these investigations, we considered the reactivity of 1,3-allenenes, such as 53 (Scheme 19).72 Our investigations suggest that gold(I)-catalyzed cycloisomerization to cyclopentadiene 55 proceeds via allylcation/Au-carbene 54.73 While we could not devise a method to quantify the degree of carbocation stabilization from gold in this particular reaction, we reasoned that the analogous 1,6-allene 56 might provide a path towards this type of insight.

Scheme 19.

Gold(I)-catalyzed 1,3-allene cycloisomerization.

Initial coordination of a cationic Au(I) catalyst to the allene moiety of 56, induces addition of the pendant olefin (Scheme 20).74 The resulting carbocation can subsequently be trapped in one of two ways. In the absence of an external nucleophile, cis-bicycle 58 is produced.75 While trans-cyclopentane 60 is produced in the presence of methanol. Furthermore, when these reactions are catalyzed by (R)-DTBM-SEGHPOS(AuCl)2 58 is produced in 92% yield and with 95% ee, while 60 is produced in 75% yield, but as a racemic mixture. Based on these results, we proposed that initial addition of the olefin to produce 59 is fast and reversible. When an external nucleophile is present, 59 is trapped; however, in the absence of such a nucleophile, the reaction funnels through 57. The formation of 57 from 56 may or may not be reversible. The exact mechanism of conversion of 57 to 58 has remained somewhat unclear. We initially hypothesized that the reaction most likely proceeds via trapping of the carbocation in 57 either by the pendant olefin to produce intermediate 61, or by the Au-C bond to directly produce 58. However, as the results below suggest, ring-contraction of gold-carbene intermediate 62 may be more likely.

Scheme 20.

Observed reaction products and possible reactive intermediates in the Au-catalyzed reactions of allene L1.

In light of these results, we were intrigued to find that Ph3PAu+ catalyzed cycloisomerization of allene-diene 63 produced a 33:67 mixture of [4 + 3] and [4 + 2] cycloadducts 64 and 65 (Scheme 21).76,77 We considered that this ratio might be altered by varying the ancillary ligand on Au. To our delight, electron-rich phosphines, including di-tert-butyl-o-biphenylphosphine provided the [4 + 3] product in high yield, while π-acidic ligands including triphenylphosphite provided exclusively the [4 + 2] adduct. This is one of the few examples of ligand-controlled divergent reactivity in Au-catalysis.29,78 Furthermore, by employing chiral, nonracemic phosphites and phosphoramidites it is possible to fully control the chemo-, diastereo- and enantioselectivity of this reaction.79

Scheme 21.

Initial experimental observations and mechanistic hypothesis in ligand-directed, Au-catalyzed [4 + 3] and [4 + 2] cycloadditions.

Based on the results from the [2 + 2] cycloadditions described above, we initially assumed that this reaction would also proceed via a stepwise addition/trapping mechanism. This would indeed explain the observed ligand effect, with electron-rich ligands stabilizing Au-carbene 66 and π-acidic ligands disfavoring this pathway.

In collaboration with the Goddard group, we initiated a theoretical study of this reaction in order to further elucidate the differences in bonding that lead to this divergent reactivity.80 These calculations suggest that both 64 and 65 are actually formed through initial concerted [4 + 3] cycloaddition, producing Au-carbene intermediate 66 (Scheme 22). A subsequent 1,2-alkyl shift (ring contraction) or 1,2-hydride shift produces the observed products. Elucidating how the ancillary ligand controls product selectivity has led to some interesting insights.

Scheme 22.

Calculated structures and transition state energies for intermediates in Au-catalyzed [4 + 3] and [4 + 2] cycloadditions.

Due to steric interactions, the Au-moiety in 66 is puckered out of the plane of the bicycle. In addition, larger ligands cause the phosphine-Au-carbon bond to distort from 180° (169° for P(tBu)2(o-biPh) versus 178° for P(OPh)3). As a result, π-donation from gold to carbon is actually reduced for the bulky, electron-rich P(tBu)2(o-biPh) and suggests that it is also important to consider sterics when attempting to predict the ability of a Au(I)-complex to stabilize an adjacent carbocation. In this reaction, increased occupation of the p-orbital on carbon in intermediate 66 disfavors the 1,2-H shift. As a result the 1,2-alkyl shift prevails with P(OPh)3 as the ancillary ligand, while the 1,2-H shift is faster with P(tBu)2(o-biPh).

5 Intermolecular Annulation Reactions

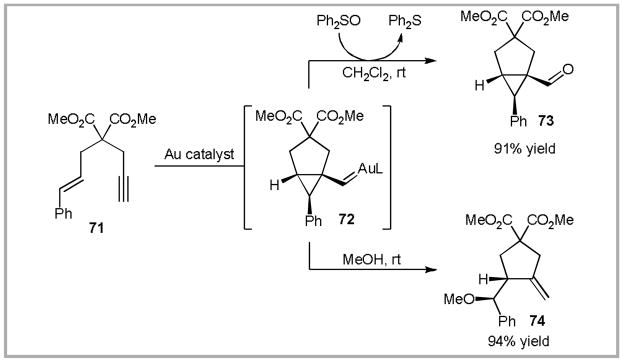

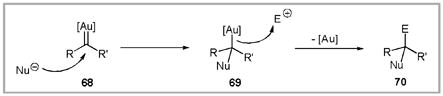

Several additional experiments aimed at trapping proposed gold carbenoid intermediates were successful. Nucleophilic addition to gold-carbenoid intermediate 68 generates a gold-carbon sigma bond. In the case of protic nucleophiles, the Au catalyst is typically regenerated by protodeauration (Equation 2, E+ = H+).81 As an example, when the reaction of enyne 71 is conducted in methanol, the cationic intermediate 72 is trapped, producing methyl ether 74 (Scheme 23).82

Scheme 23.

Observed products resulting from intermolecular trapping of intermediate A′.

|

Equation 2 |

In the case of aprotic nucleophiles the Au-C bond may be trapped by electrophiles other than a proton. Thus, trapping of the intermediate carbenoid with diphenylsulfoxide produces ketone 73 after release of diphenylsulfide.83 In addition to these reactions, Echavarren has also reported these intermediates can be trapped with olefins to produce cyclopropanation products.84 Considering these results, we hypothesized that tethering the nucleophile and electrophile in Equation 2 would allow for an intermolecular annulation reaction.85

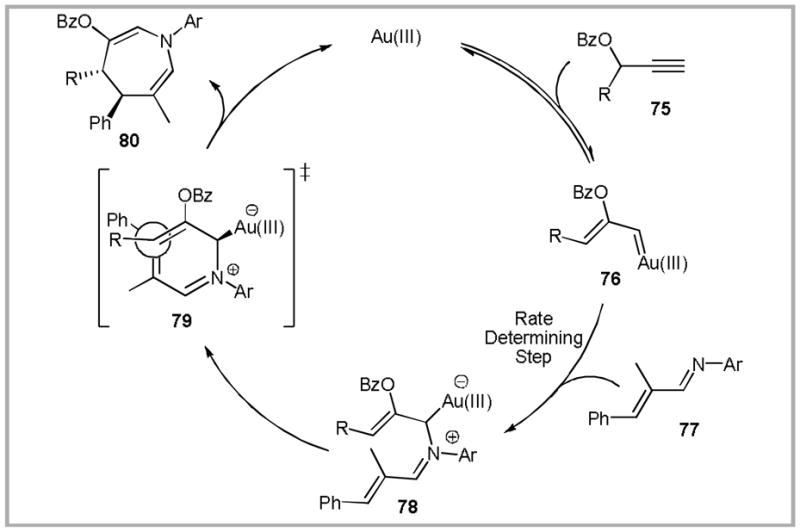

5.1A [4 + 3] Annulation Approach to Azepines

In analogy to related reactions of rhodium-stabilized carbenoids,86 we reasoned that α,β-unsaturated imines could serve as appropriate coupling partners. On the basis of this hypothesis, we were pleased to find that Au(III) catalysts87 efficiently promote the formation of azepine 80 from carbenoid precursor 75 and imine 77 (Scheme 24).88 Based on the observed trans diastereoselectivity observed with secondary propargyl esters, we proposed that the cyclization occurs via transition state 79. Overall, this transformation constitutes an example of the reactivity paradigm that we had initially set out to observe (trapping of a Au-carbenoid with a tethered nucleophile-electrophile pair).

Scheme 24.

Proposed mechanism of Au(III)-catalyzed azepine synthesis.

Further insight into this reaction was acquired through a Hammett analysis, which showed that the rate of the reaction is enhanced by electron-donating substituents on the N-Aryl and β-Aryl groups.89 This supports our stepwise mechanism, and suggests that formation of 78 from carbenoid intermediate 76 is rate determining. In addition, this result implies that nucleophilic addition of C-aryl imines to 76 should occur despite the absence of a double bond for subsequent 7-membered ring formation. We were therefore curious to investigate potential dearomatization/annulation reactions. To our delight, heteroaromatic imines (i.e. 82) could indeed by dearomatized via this methodology (Equation 3).

|

Equation 3 |

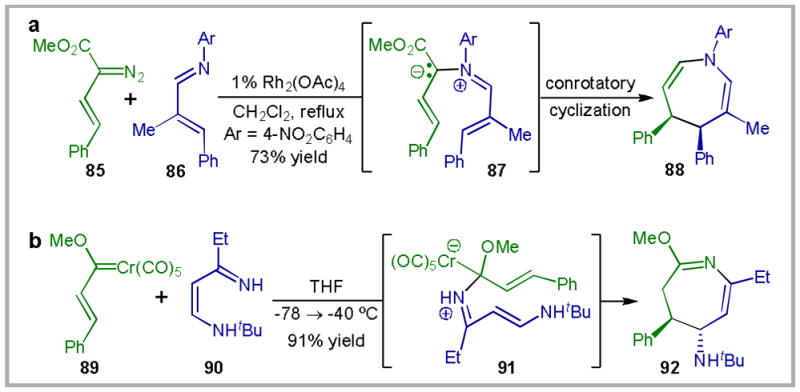

The proposed reaction mechanism for this transformation is particularly interesting in comparison to those that have been previously proposed for related reactions of rhodium-carbenoids and Fischer carbenes (Scheme 25). The Rh2(OAc)4-catalyzed decomposition of vinyl diazoester 85 in the presence of imine 86 is proposed to generate free ylide 87, which undergoes a thermally allowed 8-electron electrocyclization to produce cis-substituted azepine 88.86a In contrast, the stoichiometric reaction of 4-amino-1-aza-butadiene 90 with Fischer carbene 89 is proposed to produce trans-substituted azepine 92 via a transition state (91) that is quite similar to that proposed for the gold(III)-catalyzed reaction (79).86d In this respect, the gold-catalyzed reaction can be considered a valuable alternative to the use of stoichiometric amounts of chromium reagents. On the other hand, it should be noted that these three reactions (Rh-catalyzed, Au-catalyzed, and Cr-mediated) provide access to azepines with complementary substitution patterns.

Scheme 25.

Transition-metal catalyzed (a), and mediated (b) annulations of α,β-unsaturated imines.

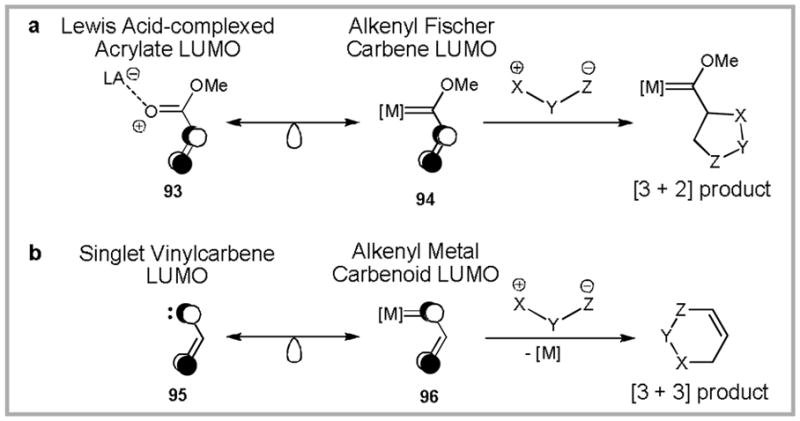

5.2 Orbital Considerations in [3 + 3] Annulations

In light of these comparisons, we were curious to investigate gold-catalyzed annulation reactions of 1,3-dipoles, a type of transformation that is well known for alkenyl Fischer carbenes90, but remains unprecedented for both free and metal-coordinated electrophilic alkenyl carbenes.91 Reaction of alkenyl Fischer carbenes with 1,3-dipoles typically proceeds via concerted-asynchronous [3 + 2] cycloaddition. The regioselectivity of this cycloaddition can be rationalized by considering the molecular orbitals involved (Scheme 26). The LUMO of Fischer carbene 94 is isolobal with that of Lewis acid complexed acrylate 93.92 As such, cycloaddition with 1,3-dipoles proceeds via [3 + 2] cycloaddition with the alkenyl fragment. In contrast, the LUMO of alkenyl metal carbenoid 96 can be approximated by free singlet vinylcarbene 95.93 Given this analogy, a [3 + 3]-cycloaddition between 1,3-dipoles and carbenoid 96 would be predicted. However, as mentioned previously, this type of reactivity had not been reported at the time we began our investigations.

Scheme 26.

Isolobal analogies of (a) alkenyl Fischer carbenes and (b) alkenyl metal carbenoids lead to predictions of distinct regioselectivity in the reaction of these species with 1,3-dipoles.

We were therefore delighted to find that the picolinic acid derived Au(III) complex 83 efficiently catalyses the [3 + 3] annulation of azomethine imines and propargyl esters (Equation 4).94 Mechanistic investigations suggest a stepwise mechanism similar to that proposed for the Au-catalyzed [4 + 3] annulation of imines and propargyl esters (vide supra).88 In addition, this reaction serves to highlight the differences in the reactivity of alkenyl Fischer carbenes and the alkenyl Au-carbenoids.

|

Equation 4 |

6 Tandem Reactions

The ability to affect multiple, mechanistically distinct, bond-forming events into a single reaction sequence allows the rapid and efficient construction of complex molecular structures.95 The design of tandem reactions requires an intricate understanding of reactivity. Each reaction must occur in the proper order and with high fidelity in order to ensure a high yield of the product. In our own research, we have developed several tandem reactions, and in doing so, have utilized several general strategies to ensure that these requirements are met.

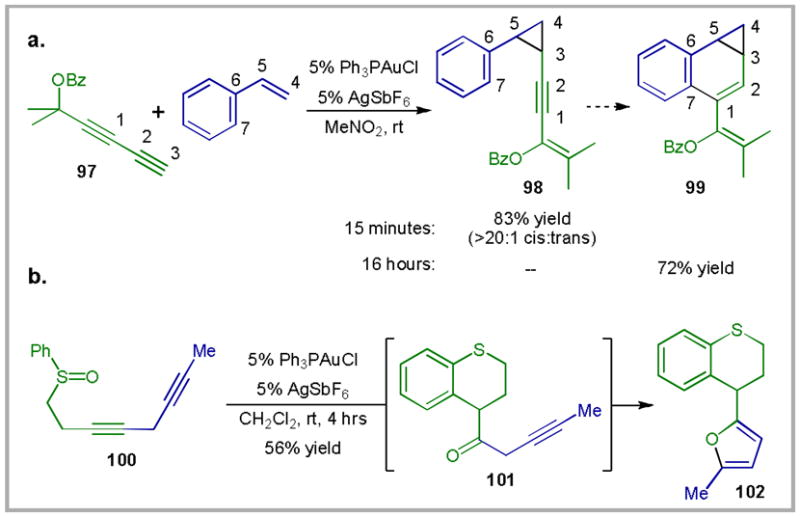

One strategy is to employ sequential intramolecular/intermolecular reactions. As an example, in what is overall a [4C + 3C] annulation, the intermolecular cyclopropanation of styrene with propargyl-ester containing diyne 97 can be coupled to an intramolecular hydroarylation (Scheme 27a).96 This sequence utilizes the knowledge that the gold(I)-catalyzed intermolecular cyclopropanation reaction occurs rapidly at room temperature (in this case, within 15 minutes).56 This allows substrate-controlled regioselectivity in the subsequent intramolecular hydroarylation. If the rate of intermolecular hydroarylation was faster than or similar to the rate of cyclopropanation, then controlling the regioselectivity of the hydroarylation could become problematic.97 A similar strategy is employed in the annulation of enynes or propargyl esters to form fluorenes or styrenes.78b

Scheme 27.

Gold(I)-catalyzed tandem cyclization reactions.

An alternative strategy for the design of tandem reactions employs reactions that create functional groups that can undergo a second metal-catalyzed transformation. This strategy was employed in the bis-cyclization of diyne sulfoxide 100: the ketone created in the first cyclization is subsequently transformed into the furan moiety of 102 (Scheme 27b).

Similarly, propargyl Claisen rearrangement of vinyl ether 103 forms allenyl aldehyde 104.98 In the presence of water, the aldehyde moiety will undergo further cyclization onto the allene, forming dihydropyran 105 (Scheme 28).99 By excluding water from this reaction, cyclopropane-substituted allene 104 undergoes ring expansion to form cyclopentene 106.100

Scheme 28.

Tandem propargyl-Claisen/cyclization reactions.

7 Conclusions

In this account, we have attempted to illustrate the thought process and experimental testing that occurs throughout a reactivity-based approach to reaction discovery.5 In practice, this ‘method’ of organic chemistry research frequently involves close inspection of reaction mechanism, as well as the ability to identify and creatively expand upon reactivity paradigms. On a personal level, we have enjoyed the freedom to investigate new reactions that is afforded by this research method. But above all else, it is potential impact of discovering new reactivity, mechanisms and reactions that provides the driving force for this research program:

The goals is always finding something new, hopefully unimagined and, better still, hitherto unimaginable.

– Professor K. Barry Sharpless5a

Acknowledgments

We are highly indebted to our talented colleagues and collaborators that have contributed to the work described in this account. We gratefully acknowledge the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM073932) for funding this research program and for financial support from Merck, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Amgen, Dupont, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbott, Amgen, Pfizer, AstraZeneca and Novartis. We would like to thank Takasago and Solvias for generous donation of chiral ligands and Johnson Matthey for a gift of gold salts. N.D.S. would like to thank Eli Lilly and Novartis for graduate fellowships.

Biography

Dean Toste was born in Terceira, Azores, Portugal but soon moved to Toronto, Canada. He received his B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in chemistry from the University of Toronto, Canada where he worked with Prof. Ian W. J. Still. In 1995, he began his doctoral studies at Stanford University under the direction of Professor Barry M. Trost. Following postdoctoral studies with Professor Robert H. Grubbs at Caltech, he joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley in July of 2002, and was promoted to Associate Professor in 2006. Current research in his group is aimed towards the design of metal catalysts and metal-catalyzed reactions and the application of these methods to chemical synthesis. He has received numerous awards including the Camille and Henry Dreyfus New Faculty Award (2002), Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship (2005), National Science Foundation CAREER Award (2005), Cope Scholar Award (2006) and the EJ Corey Award (2008) from the American Chemical Society, BASF Catalysis Award (2007) and the OMCOS (2007) and Thieme Award (2008) from IUPAC.

Dean Toste was born in Terceira, Azores, Portugal but soon moved to Toronto, Canada. He received his B.Sc. and M.Sc. degrees in chemistry from the University of Toronto, Canada where he worked with Prof. Ian W. J. Still. In 1995, he began his doctoral studies at Stanford University under the direction of Professor Barry M. Trost. Following postdoctoral studies with Professor Robert H. Grubbs at Caltech, he joined the faculty at the University of California, Berkeley in July of 2002, and was promoted to Associate Professor in 2006. Current research in his group is aimed towards the design of metal catalysts and metal-catalyzed reactions and the application of these methods to chemical synthesis. He has received numerous awards including the Camille and Henry Dreyfus New Faculty Award (2002), Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship (2005), National Science Foundation CAREER Award (2005), Cope Scholar Award (2006) and the EJ Corey Award (2008) from the American Chemical Society, BASF Catalysis Award (2007) and the OMCOS (2007) and Thieme Award (2008) from IUPAC.

References

- 1.Lewis GN. Science. 1909;30:1. doi: 10.1126/science.30.757.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.For recent discussions relevant to this approach see: Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403799101.Mohr JT, Krout MR, Stoltz BM. Nature. 2008;455:323. doi: 10.1038/nature07370.Shenvi RA, O’Malley DP, Baran PS. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:530. doi: 10.1021/ar800182r.Wender PA, Verma VA, Paxton TJ, Pillow TH. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:40. doi: 10.1021/ar700155p.Young IS, Baran PS. Nature Chem. 2009;1:193. doi: 10.1038/nchem.216.Morten CJ, Byers JA, Van Dyke AR, Vilotijevic I, Jamison TF. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:3175. doi: 10.1039/b816697h.

- 3.(a) Grubbs RH, Chang S. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4413. [Google Scholar]; (b) Dick AR, Sanford MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartwig JF. Nature. 2008;455:314. doi: 10.1038/nature07369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Buchwald SL. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1439. doi: 10.1021/ar8001798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Sherry BD, Fürstner A. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1500. doi: 10.1021/ar800039x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Fu GC. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1555. doi: 10.1021/ar800148f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Afagh NA, Yudin AK. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009 doi: 10.1002/anie.200901317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Francis MB, Jamison TF, Jacobsen EN. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 1998;2:422. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(98)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Weber L, Illgen K, Almstetter M. Synlett. 1999:366. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kanan MW, Rozenman MM, Sakurai K, Snyder TM, Liu DR. Nature. 2004;431:545. doi: 10.1038/nature02920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Beeler AB, Su S, Singleton CA, Porco JA., Jr J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1413. doi: 10.1021/ja0674744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rozenman MM, Kanan MW, Liu DR. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:14933. doi: 10.1021/ja074155j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Gorin DJ, Kamlet AS, Liu DR. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9189. doi: 10.1021/ja903084a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.For selected examples that highlight this approach, see: Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2024.Johnson JS, Evans DA. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:325. doi: 10.1021/ar960062n.Fu GC. Acc Chem Res. 2000;33:412. doi: 10.1021/ar990077w.Fulton JR, Holland AW, Fox DJ, Bergman RG. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:44. doi: 10.1021/ar000132x.Trost BM. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:695. doi: 10.1021/ar010068z.Saito S, Yamamoto H. Acc Chem Res. 2004;37:570. doi: 10.1021/ar030064p.Enders D, Neimeier O, Henseler A. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5606. doi: 10.1021/cr068372z.MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2008;455:304. doi: 10.1038/nature07367.Doyle AG, Jacobsen EN. Chem Rev. 2007;107:5713. doi: 10.1021/cr068373r.

- 6.Teles JH, Brode S, Chabanas M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1998;37:1415. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980605)37:10<1415::AID-ANIE1415>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nesmeyanov AN, Grandberg KI, Dyadchenko VP, Lemenovskii DA, Perevalova EG. Izv Akad Nauk SSSR, Ser Khim. 1974:1206. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kennedy-Smith JJ, Staben ST, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:4526. doi: 10.1021/ja049487s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The thermally promoted Conia-ene reaction typically proceeds at temperatures above 200 °C. For a review, see: Conia JM, Le Perchec P. Synthesis. 1975:1.

- 10.For additional metal promoted Conia-ene reactions, see: Pd-catalyzed: Balme G, Bouyssi D, Faure R, Gore J, Van Hemelryck B. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:3891.Mo-catalyzed: McDonald FE, Olson TC. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:7691.Cu-catalyzed: Bouyssi D, Monteiro N, Balme G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:1297.Ti-mediated: Kitagawa O, Suzuki T, Inoue T, Watanabe Y, Taguchi T. J Org Chem. 1998;63:9470.Hg/H+-catalyzed: Boaventura MA, Drouin J, Conia JM. Synthesis. 1983:801.Co/hv-catalyzed: Renaud JL, Aubert C, Malacria M. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:5113.Ni-catalyzed: Gao Q, Zheng BF, Li JH, Yang D. Org Lett. 2005;7:2185. doi: 10.1021/ol050532q.Re-catalyzed: Kuninobu Y, Kawata A, Takai K. Org Lett. 2005;7:4823. doi: 10.1021/ol0515208.

- 11.A 5-endo-dig variant of this reaction is also viable, see: Staben ST, Kennedy-Smith JJ, Toste FD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;43:5350. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460844.

- 12.For a similar study, see: Hashmi ASK, Weyrauch JP, Frey W, Bats JW. Org Lett. 2004;6:4391. doi: 10.1021/ol0480067.

- 13.(a) Akana JA, Bhattacharyya KX, Müller P, Sadighi JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:7736. doi: 10.1021/ja0723784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu LP, Xu B, Mashuta MS, Hammond GB. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17642. doi: 10.1021/ja806685j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hashmi ASK, Schuster AM, Rominger F. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:8247. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.We hypothesize that the Brønsted acid suppresses alkyne dimerization, while the Lewis acid increases the enolic character of the ketoester, see also: Trost BM, Sorum MT, Chan C, Harms AE, Rühter G. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:698.

- 15.(a) Staben ST, Kennedy-Smith JJ, Huang D, Corkey BK, LaLonde RL, Toste FD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:5991. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Corkey BK, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2764. doi: 10.1021/ja068723r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linghu X, Kennedy-Smith JJ, Toste FD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:7671. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For reviews of enantioselective hydroamination, see: Hultzsch KC. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:1819. doi: 10.1039/b418521h.Hultzsch KC. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347:367.

- 18.LaLonde RL, Sherry BD, Kang EJ, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2452. doi: 10.1021/ja068819l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton GL, Kang EJ, Miriam M, Toste FD. Science. 2007;317:496. doi: 10.1126/science.1145229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.For another study on the Au(I)-catalyzed asymmetric hydroalkoxylation of allenes, see: Zhang Z, Widenhoefer RA. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:283. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603260.

- 21.LaLonde RL, Wang ZJ, Mba M, Lackner AD, Toste FD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009 doi: 10.1002/anie.200905000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.For a review of chiral anion mediated asymmetric chemistry, see: Lacour J, Hebbe-Viton V. Chem Soc Rev. 2003;32:373. doi: 10.1039/b205251m.

- 23.For other metal-catalyzed chiral-anion mediated asymmetric reactions, see: Llewellyn DB, Adamson D, Arndtsen BA. Org Lett. 2000;2:4165. doi: 10.1021/ol000303y.Llewellyn DB, Arndtsen BA. Tetrahedron-Asymmetry. 2005;16:1789.Dorta R, Shimon L, Milstein D. J Organomet Chem. 2004;689:751.Mukherjee S, List B. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11336. doi: 10.1021/ja074678r.Hu WH, Xu XF, Zhou J, Liu WJ, Huang HX, Hu J, Yang LP, Gong LZ. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:7782. doi: 10.1021/ja801755z.Li C, Wang C, Villa-Marcos B, Xiao J. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14450. doi: 10.1021/ja807188s.Li C, Villa-Marcos B, Xiao J. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6967. doi: 10.1021/ja9021683.Lu Y, Johnstone TC, Arndtsen BA. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11284. doi: 10.1021/ja904185b.

- 24.Ito Y, Sawamura M, Hayashi T. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:6405. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melhado AD, Luparia M, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12638. doi: 10.1021/ja074824t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.For a racemic, Ag-catalyzed variant of this reaction, see: Peddibhotla S, Tepe J. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:12776. doi: 10.1021/ja046149i.

- 27.Müller TE, Beller M. Chem Rev. 1998;98:675. doi: 10.1021/cr960433d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markham JP, Staben ST, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:9708. doi: 10.1021/ja052831g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.For a review of ligand effects in gold catalysis, see: Gorin DJ, Sherry BD, Toste FD. Chem Rev. 2008;108:3351. doi: 10.1021/cr068430g.

- 30.Theoretical calculations support this mechanism, see: Sordo TL, Ardura D. Eur J Org Chem. 2008:3004.

- 31.For a review of 1,2-alkyl migrations catalyzed by π acids, see: Crone B, Kirsch SF. Chem-Eur J. 2008;14:3514. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701985.

- 32.Sethofer SG, Staben ST, Hung OY, Toste FD. Org Lett. 2008;10:4315. doi: 10.1021/ol801760w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinbeck F, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9178. doi: 10.1021/ja904055z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.For other reports of catalytic asymmetric ring expansion, see: Trost BM, Yasukata T. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7162. doi: 10.1021/ja010504c.Trost BM, Xie J. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6044. doi: 10.1021/ja0602501.Trost BM, Xie J, Maulide N. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:17258. doi: 10.1021/ja807894t.

- 35.Markownikoff W. Liebigs Ann. 1870;153:228. [Google Scholar]

- 36.For related reactions, see: Cacchi S, Fabrizi G, Pace P. J Org Chem. 1998;63:1001.Fürstner A, Szillat H, Stelzer F. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:6785. doi: 10.1021/ja0109343.Shimada T, Nakamura I, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10546. doi: 10.1021/ja047542r.Nakamura I, Mizushima Y, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:15022. doi: 10.1021/ja055202f.Nakamura I, Sato T, Yamamoto Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. Vol. 45. 2006. p. 4473.Istrate FM, Gagosz F. Org Lett. 2007;9:3181. doi: 10.1021/ol0713032.Nakamura I, Yamagishi U, Song D, Konta S, Yamamoto Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:2284. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604038.Nakamura I, Sato T, Terada M, Yamamoto Y. Org Lett. 2007;9:4081. doi: 10.1021/ol701951n.Nakamura I, Sato T, Terada M, Yamamoto Y. Org Lett. 2008;10:2649. doi: 10.1021/ol8007556.Uemura M, Watson IDG, Katsukawa M, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3464. doi: 10.1021/ja900155x.

- 37.Dubé P, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:12062. doi: 10.1021/ja064209+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.For a review of “memory of chirality”, see: Zhao H, Hsu DC, Carlier PR. Synthesis. 2005:1.

- 39.For studies on the Ag/Cu catalyzed Conia-ene reaction, see: Deng CL, Zou T, Wang ZQ, Song RJ, Li JH. J Org Chem. 2009;74:412. doi: 10.1021/jo802133w.

- 40.Shapiro ND, Toste FD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2779. [Google Scholar]

- 41.For other reports of Au-alkyne complexes, see reference 13a, and: Schulte P, Behrens U. Chem Commun. 1998:1633.Flügge S, Anoop A, Goddard R, Thiel W, Fürstner A. Chem –Eur J. 2009;15:8558. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901062.For a review, see: Schmidbaur H, Schier A. Organometallics. 2009 doi: 10.1021/om900900u.

- 42.For similar studies, see: Nechaev MS, Rayón VM, Frenking G. J Phys Chem A. 2004;108:3134.Ziegler T, Rauk A. Inorg Chem. 1979;18:1558.Hertwig RH, Koch W, Schröder D, Schwarz H, Hrušák J, Schwerdtfeger P. J Phys Chem. 1996;100:12253.Kim CK, Lee KA, Kim CK, Lee B, Lee HW. Chem Phys Lett. 2004;391:321.Tai HC, Krossing I, Seth M, Deubel DV. Organometallics. 2004;23:2343.

- 43.Luzung MR, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15760. doi: 10.1021/ja039124c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luzung MR, Markham JP, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10858. doi: 10.1021/ja046248w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.For related reports, see: Mamane V, Gress T, Krause H, Fürstner A. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8654. doi: 10.1021/ja048094q.Harrak Y, Blaszykowski C, Bernard M, Cariou K, Mainetti E, Mouriés V, Dhimane AL, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8656. doi: 10.1021/ja0474695.Horino Y, Luzung MR, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:11364. doi: 10.1021/ja0636800.

- 46.For reviews on cycloisomerizations, see: Aubert C, Buisine O, Malacria M. Chem Rev. 2002;102:813. doi: 10.1021/cr980054f.Trost BM, Krische MJ. Synlett. 1998:1.Ojima I, Tzamarioudaki M, Li Z, Donovan RJ. Chem Rev. 1996;96:635. doi: 10.1021/cr950065y.

- 47.Gorin DJ, Davis NR, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11260. doi: 10.1021/ja053804t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4160. doi: 10.1021/ja070789e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.For reviews, see: Wee AGH. Curr Org Synth. 2006;3:499.Davies HML, Beckwith REJ. Chem Rev. 2003;103:2861. doi: 10.1021/cr0200217.Davies HML, Antoulinakis EG. Org React. 2001;57:1.Ye T, McKervey MA. Chem Rev. 1994;94:1091.Doyle MP, McKervey MA, Ye T, editors. Modern Catalytic Methods for Organic Synthesis with Diazo Compounds. Wiley; New York: 1998. Zaragoza-Dorwald F, editor. Metal-Carbenes in Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 1998.

- 50.For gold-catalyzed reaction of α-diazoesters, see: Fructos MR, Belderrain TR, de Frémont P, Scott NM, Nolan SP, Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:5284. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501056.Fructos MR, de Frémont P, Nolan SP, Díaz-Requejo MM, Pérez PJ. Organometallics. 2006;25:2237.

- 51.Rautenstrauch V. J Org Chem. 1984;49:950. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi X, Gorin DJ, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5802. doi: 10.1021/ja051689g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faza ON, Lôpez CS, Álvarez R, de Lera AR. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2434. doi: 10.1021/ja057127e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Closs GL, Moss RA. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:4042. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Skell PS, Woodworth RC. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78:4496. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johansson MJ, Gorin DJ, Staben ST, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:18002. doi: 10.1021/ja0552500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miki K, Ohe K, Uemura S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003;44:2019.Miki K, Ohe K, Uemura S. J Org Chem. 2003;68:8505. doi: 10.1021/jo034841a.Miki K, Uemura S, Ohe K. Chem Lett. 2005;34:1068.For a related gold-(III)-catalyzed intramolecular cyclopropanation, see: Fürstner A, Hannen P. Chem Commun. 2004:2546. doi: 10.1039/b412354a.

- 58.For a review of enantioselective cyclopropanation, see: Lebel H, Marcoux JF, Molinaro C, Charette AB. Chem Rev. 2003;103:977. doi: 10.1021/cr010007e.

- 59.Watson IDG, Ritter S, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2056. doi: 10.1021/ja8085005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.(a) Fürstner A, Szillat H, Gabor B, Mynott R. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8305. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fürstner A, Stelzer F, Szillat H. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11863. doi: 10.1021/ja0109343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Nieto-Oberhuber C, Muñoz MP, Buñuel E, Nevado C, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:2402. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chatani N, Kataoka K, Murai S, Furukawa N, Seki Y. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:9104. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pitzer KS. Acc Chem Res. 1979;12:271. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwerdtfeger P, Boyd PDW, Burrell AK, Robinson WT, Taylor MJ. Inorg Chem. 1990;29:3593. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Benitez D, Shapiro ND, Tkatchouk E, Wang Y, Goddard WA, III, Toste FD. Nature Chem. 2009;1:482. doi: 10.1038/nchem.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Irikura KK, Goddard WA., III J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:8733. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Landis CR, Weinhold F. J Comput Chem. 2007;28:198. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.This model is highly reminiscent of the double ‘half-bond’ model proposed for rhodium carbenoid intermediates, see: Snyder JP, Padwa A, Stengel T, Arduengo AJ, III, Jockisch A, Kim H-L. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:11318. doi: 10.1021/ja016928o.Costantino G, Rovito R, Macchiarulo A, Pellicciari R. J Mol Struct Theochem. 2002;581:111.

- 68.Horino Y, Yamamoto T, Ueda K, Kuroda S, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2809. doi: 10.1021/ja808780r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.For a related study, see: Lemière G, Gandon V, Cariou K, Hours A, Fukuyama T, Dhimane AL, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:2993. doi: 10.1021/ja808872u.

- 70.For related metal-catalyzed C(sp3)-H bond insertions, see reference 50b, and: Bhunia S, Liu RS. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16488. doi: 10.1021/ja807384a.Lee SJ, Oh CH, Lee JH, Kim JI, Hong CS. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:7505. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802425.Cui L, Peng Y, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8394. doi: 10.1021/ja903531g.

- 71.Jones WD. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:140. doi: 10.1021/ar020148i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee JH, Toste FD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:912. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.For related transformations, see: Zhang L, Wang S. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:1442. doi: 10.1021/ja057327q.Funami H, Kusama H, Iwasawa N. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2007;46:909. doi: 10.1002/anie.200603986.Lemière G, Gandon V, Cariou K, Fukuyama T, Dhimane AL, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Org Lett. 2007;9:2207. doi: 10.1021/ol070788r.

- 74.Luzung MP, Mauleón P, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12402. doi: 10.1021/ja075412n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.For a related mechanism, see: Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:16804. doi: 10.1021/ja056419c.

- 76.Mauleón P, Zeldin RM, González AZ, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:6348. doi: 10.1021/ja901649s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.For related studies, see: Trillo B, López F, Montserrat S, Ujaque G, Castedo L, Lledós A, Mascareñas JL. Chem-Eur J. 2009;15:3336. doi: 10.1002/chem.200900164.Alonso I, Trillo B, López F, Montserrat S, Ujaque G, Castedo L, Lledós A, Mascareñas JL. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13020. doi: 10.1021/ja905415r.

- 78.See also: Lemière G, Gandon V, Agenet N, Goddard JP, de Kozak A, Aubert C, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:7596. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602189.Gorin DJ, Watson IDG, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:3736. doi: 10.1021/ja710990d.Xia Y, Dudnik AS, Gevorgyan V, Li Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6940. doi: 10.1021/ja802144t.

- 79.Gonzalez A, Toste FD. Org Lett. 2010 doi: 10.1021/ol902622b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Benitez D, Tkatchouk E, González A, Goddard WA, III, Toste FD. Org Lett. 2009;11:4798. doi: 10.1021/ol9018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.(a) Amijs CHM, López-Carrillo V, Echavarren AM. Org Lett. 2007;9:4021. doi: 10.1021/ol701706d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Leseurre L, Toullec PY, Genêt JP, Michelet V. Org Lett. 2007;9:4049. doi: 10.1021/ol7017483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Echavarren AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:6178. doi: 10.1021/ja042257t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Witham CA, Mauleón P, Shapiro ND, Sherry BD, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:5838. doi: 10.1021/ja071231+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.(a) Nieto-Oberhuber C, Paz Muñoz M, López S, Jiménez-Núñez E, Nevado C, Herrero-Gómez E, Raducan M, Echavarren AM. Chem-Eur J. 2006;12:1677. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Paz Muñoz M, Jiménez-Núñez E, Bunuel E, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Chem-Eur J. 2006;12:1694. doi: 10.1002/chem.200501089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) López S, Herrero-Gómez E, Pérez-Galán P, Nieto-Oberhuber C, Echavarren AM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:6029. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.For related Au-catalyzed intermolecular annulations, see: Asao N, Takahashi K, Lee S, Kasahara T, Yamamoto Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:12650. doi: 10.1021/ja028128z.Kusama H, Miyashita Y, Takaya J, Iwasawa N. Org Lett. 2006;8:289. doi: 10.1021/ol052610f.Zhang G, Huang X, Li G, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:1814. doi: 10.1021/ja077948e.Zhang G, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12598. doi: 10.1021/ja804690u.

- 86.Doyle MP, Hu W, Timmons DJ. Org Lett. 2001;3:3741. doi: 10.1021/ol016703i.Doyle MP, Yan M, Hu W, Gronenberg LS. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4692. doi: 10.1021/ja029745q.Davies HML, Hu B, Saikali E, Bruzinski PR. J Org Chem. 1994;59:4535.For related reactions of Fischer carbenes, see: Barluenga J, Tomás M, Ballesteros A, Santamaria J, Carbajo RJ, López-Ortiz F, Garcia-Granda S, Pertierra P. Chem-Eur J. 1996;2:88.Barluenga J, Tomás M, Rubio E, López-Pelegrín JA, García-Granda S, Priede MP. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:3065.

- 87.(a) Hashmi ASK, Weyrauch JP, Rudolph M, Kurpejoviæ E. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:6545. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hashmi ASK, Kurpejoviæ E, Wölfle M, Frey W, Bats JW. Adv Synth Catal. 2007;349:1743. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9244. doi: 10.1021/ja803890t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. Chem Rev. 1991;91:165. [Google Scholar]

- 90.(a) Barluenga J, Rodrígues F, Fañañas FJ, Flórez J. Top Organomet Chem. 2004;13:59. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barluenga J, Santamaría J, Tomás M. Chem Rev. 2004;104:2259. doi: 10.1021/cr0306079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sierra MA, Fernández I, Cossío FP. Chem Commun. 2008:4671. doi: 10.1039/b807806h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bertrand G, editor. FontisMedia. Lausanne, Dekker; New York: 2002. Carbene Chemistry: From Fleeting Intermediates to Powerful Reagents.Moss RA, Platz MS, Jones M Jr, editors. Reactive Intermediate Chemistry. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. Nucleophilic singlet vinylcarbenes react as 3-carbon units in cycloadditions with olefins; see: Boger DL, Wysocki RJ., Jr J Org Chem. 1988;53:3408.

- 92.Sierra MA, Fernández I, Cossío FP. Chem Commun. 2008:4671. doi: 10.1039/b807806h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.(a) Hoffmann R, Zeiss GD, Van Dine GW. J Am Chem Soc. 1968;90:1485. [Google Scholar]; (b) Davis JH, Goddard WA, III, Bergman RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:2427. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sevin A, Arnaud-Danon L. J Org Chem. 1981;46:2346. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yoshimine M, Pacansky J, Honjou N. J Am Chem Soc. 1989;111:2785. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shapiro ND, Shi Y, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:11654. doi: 10.1021/ja903863b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walji AM, MacMillan DWC. Synlett. 2007:1477. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gorin DJ, Dubé P, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14480. doi: 10.1021/ja066694e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.(a) Reetz MT, Sommer K. Eur J Org Chem. 2003:3485. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shi Z, He C. J Org Chem. 2004;69:3669. doi: 10.1021/jo0497353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tarselli MA, Liu A, Gagne MR. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1785. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.10.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sherry BD, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15978. doi: 10.1021/ja044602k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sherry BD, Maus L, Laforteza BN, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8132. doi: 10.1021/ja061344d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mauleón P, Krinsky JL, Toste FD. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4513. doi: 10.1021/ja900456m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]