Abstract

Objectives

To assess students' performance and perceptions of team-based and mixed active-learning methods in 2 ambulatory care elective courses, and to describe faculty members' perceptions of team-based learning.

Methods

Using the 2 teaching methods, students' grades were compared. Students' perceptions were assessed through 2 anonymous course evaluation instruments. Faculty members who taught courses using the team-based learning method were surveyed regarding their impressions of team-based learning.

Results

The ambulatory care course was offered to 64 students using team-based learning (n = 37) and mixed active learning (n = 27) formats. The mean quality points earned were 3.7 (team-based learning) and 3.3 (mixed active learning), p < 0.001. Course evaluations for both courses were favorable. All faculty members who used the team-based learning method reported that they would consider using team-based learning in another course.

Conclusions

Students were satisfied with both teaching methods; however, student grades were significantly higher in the team-based learning course. Faculty members recognized team-based learning as an effective teaching strategy for small-group active learning.

Keywords: team-based learning, active learning, ambulatory care elective course

INTRODUCTION

Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) Standards identify the development of critical thinking and problem-solving skills, and the transition to active learning as key components of pharmacy education.1 The pharmacy profession also has placed added demands for competent, self-directed graduates as the profession continues to advance in practicing patient-centered care. The 2004 revision of the Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes describes competencies in patient-centered care requiring higher levels of knowledge, skill, and social/ethical awareness from graduating pharmacists.2 The skills and outcomes described by ACPE and CAPE can be achieved through active-learning methods. The generally accepted definition of active learning is for students to use 1 or more of the following elements: talking and listening, writing, reading, and reflecting.3 Active learning also requires students to be involved in higher-order thinking and to focus on skill development.4

Blouin and colleagues challenged pharmacy educators to focus on 3 areas to improve the delivery of education to young adults: (1) limit class time used for passive transmission of factual information to students; instead direct students to obtain this information so that class time may be spent teaching the “why” and exploring the “how”; (2) challenge students to develop critical-thinking, communication, and problem-solving skills; and (3) adopt a practice of “evidence-based education.”5 These focus areas must be incorporated simultaneously to produce the necessary changes in pharmacy education, and they may be accomplished through various active-learning methods. At the time of this writing, the effectiveness of different active-learning methods has not been compared in the pharmacy education literature.

Cooperative learning is a type of active learning that incorporates small groups of students working together to complete a task. This method provides opportunities to develop social, communication, and group processing skills.3,4 Team-based learning is a structured method of cooperative learning that has been implemented in a variety of learning environments since the late 1970s.6 Team-based learning has been introduced to health science education,7-12 with the first account of team-based learning in pharmacy education literature in 2008.11 The goal of team-based learning is to develop a student's ability to achieve higher levels of cognitive learning by applying their knowledge in a team (cooperative learning) environment.6 Beyond learning the course material, students develop skills in critical thinking, communication, interpersonal relationships, teamwork, and consensus building. Team-based learning also incorporates student accountability along with judgment (clinical decision making) to promote higher-order thinking and to allow students to apply course concepts in context. Team-based learning maintains the same effectiveness as small-group learning in classroom sizes with student-faculty ratios up to 200:1.6

With the implementation of active learning, many of the desired ACPE and CAPE outcomes and competencies can be developed in the classroom. From a faculty or administrative point of view, a potential barrier to implementing active learning is the perceived increase in faculty-student ratios and faculty members' time required to deliver a course using active-learning methods. The question remains, is there an active-learning method which could be incorporated into the doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) curriculum that: (1) provides evidence of learning; (2) is accepted by students and faculty members; and (3) does not increase demands of faculty resources? To answer this question, we assessed and compared student performance and student-centered perceptions in 2 ambulatory care elective courses at our college, 1 that used team-based learning and 1 that incorporated a mixture of active-learning methods. We also reported the perceptions of those faculty members who were involved with the team-based learning course delivery.

The Ambulatory Care elective was a 2-credit-hour course offered during the third year (P3). The college expanded to 2 campuses, with student enrollment at both locations beginning in August 2007. The elective had been developed on the Memphis, TN, campus using mixed active-learning methods for approximately 10 years. With the college's expansion to Knoxville, the elective initially was taught using mixed active learning, but was converted to team-based learning in July 2008. Since the expansion, the elective has been taught concurrently on each campus during fall and spring semesters. During the fall semester, the course has consisted of 2-hour class sessions held once each week. During the spring semester, it has been taught over the course of 1 month, meeting twice weekly for 3 hours each session (mixed active learning) or 3 times weekly for 2 hours each session (team-based learning). The same faculty members have taught in both the month-long and semester-long formats, with no faculty member cross-over between campuses or between teaching methods. Students have enrolled in the mixed active or team-based learning course offerings based on campus location.

The goals of the courses were to increase students' knowledge of common disease states and opportunities in ambulatory care practice through case-based application and discussions with peers and faculty members. The courses were designed to build on ambulatory care topics included in the therapeutics curriculum. All ambulatory care-related therapeutic topics included in the elective were covered in the therapeutics curriculum prior to the elective class session.

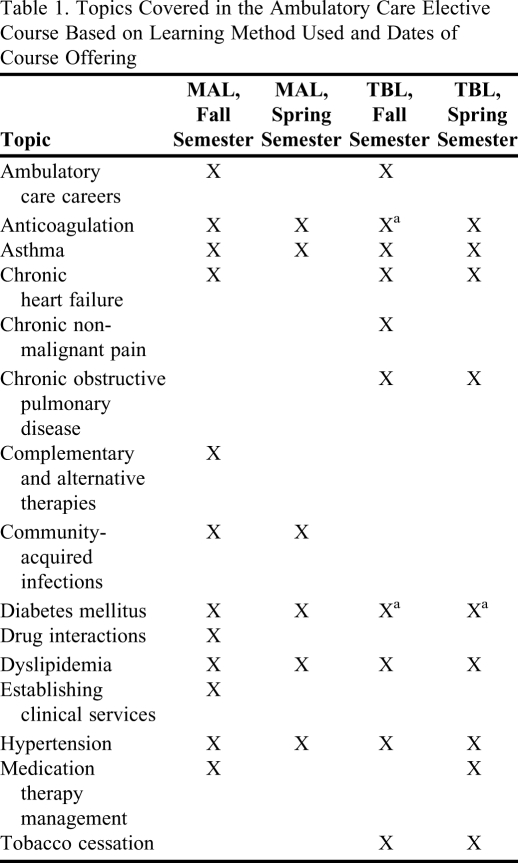

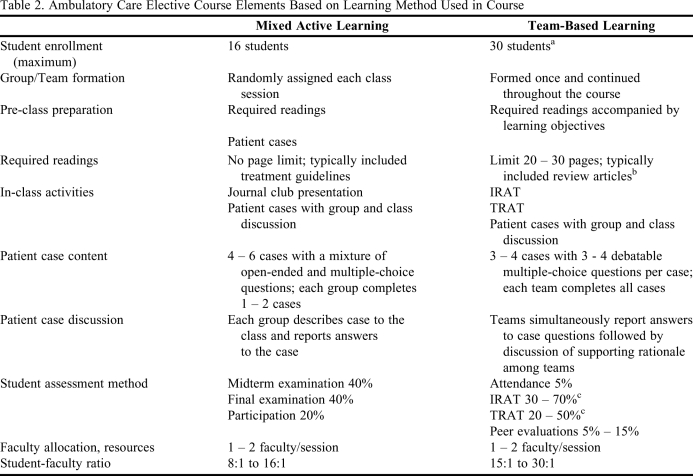

Topics covered during each of the course offerings varied slightly (Table 1). The topics for each course were selected based on the following factors: course duration, number of class sessions, and faculty members' area of expertise. The course design and elements for each method of learning are listed in Table 2. Because a complete description of team-based learning is beyond the scope of this article, readers should refer to other references for additional information.6-15 A few notable differences between the teaching methods relate to team structure and assignment format. In the team-based learning course, student team formation was completed once and those teams were maintained throughout the course. In the mixed active-learning course, students were assigned to teams at random at the start of each class session. In the team-based learning course, in-class assignments consisted of an individual readiness assurance test, followed by a team readiness assurance test, and patient case discussions. Each team worked on the same patient cases. Answers to the cases were reported simultaneously, followed by a detailed discussion led by the faculty facilitator. In-class assignments in the mixed active-learning course consisted of multiple patient cases that were divided among the student teams. The faculty member facilitated the class discussion for each patient case. In addition, during each mixed active-learning class session, 1 to 2 students were required to present a critique of a journal article from the primary literature pertaining to the topic for that session.

Table 1.

Topics Covered in the Ambulatory Care Elective Course Based on Learning Method Used and Dates of Course Offering

Abbreviations: MAL = mixed active learning, TBL = team-based learning.

aTopic spanned 2 class sessions.

Table 2.

Ambulatory Care Elective Course Elements Based on Learning Method Used in Course

IRAT = individual readiness assurance test; MAL = mixed active learning; TBL = team-based learning; TRAT = team readiness assurance test.

aClass size limited for administrative purposes, not limitations of the learning method.

bReview articles were selected to include an evidence-based review on drug therapy pertinent to the topic of the class session.

cTBL course format empowers students to determine weighted grade distributions. For detailed explanation on this process please refer to Reference 6.

METHODS

Student performance was assessed by comparing end-of-course grades for the 2 learning methods. Prior student performance was identified as a confounding factor and was adjusted for by using a hierarchical multiple regression model based on the cumulative grade point average (GPA) the students earned at the completion of the P2 courses. For the empirical purposes of building a multiple regression model, course letter grades were converted to quality points based on the college's predetermined scale (A = 4.0; A- = 3.75; B+ = 3.50; B = 3.00; B- = 2.75; C+ = 2.50; C = 2.0; C- = 1.75; D = 1.50; F = 1.0). This allowed use of a better scale of measurement to achieve significance and predictability within the model. Independent sample t tests were conducted to identify significant differences in GPA and quality points between teaching methods. Levene's test for equality of variances was used to assure statistical assumptions were met. When violations occurred, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used. The level of significance was determined a priori to be p < 0.05.

Students' perceptions were collected using 2 course evaluations for each course design. The first was a standardized college course evaluation administered via CoursEval (Academic Management Systems, Amherst, NY) to assess course elements (course content, required readings, in-class activities, pre-class assignments, course coordination, and evaluation methods). The second assessment was a course survey instrument administered via Blackboard (Blackboard Inc, Washington, DC) that evaluated course elements, student confidence with course material, and achievement of the college's ability-based outcomes. Students' responses were recorded using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree). Both course evaluations were completed on a voluntary basis. Differences among survey responses were analyzed using Mann-Whitney tests with a level of significance of p < 0.05.

A survey instrument was developed to measure faculty members' perceptions about implementing team-based learning. This subset of faculty members was selected to complete the survey instrument because they had experience in using both methods of active learning. Faculty members completed the survey instrument at the conclusion of the second team-based learning course offering. Seven questions were included on the topics of team-based learning implementation, faculty members' satisfaction, student impact, and the amount of time required to conduct a class session, including preparation, implementation, and follow-up/grading. Responses were recorded using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree). Two open-ended questions were presented to identify challenges and rewards of team-based learning. Due to the limited number of potential responses, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data.

The study was deemed exempt by our institution's Institutional Review Board. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, Version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Sixty-four students completed 1 of the 4 course offerings. Thirty-seven students completed the course using team-based learning, and 27 used mixed active learning.

Student Performance: Course Grades

No significant difference was found when comparing cumulative student GPAs prior to course entry (p = 0.83; team-based learning 3.30, mixed active learning 3.14). The mean ± standard deviation course grades based on quality points for the courses were 3.7 ± 0.2 for team-based learning, and 3.3 ± 0.5 for mixed active learning; p < 0.001. In the first step of the hierarchical regression, the analysis learning method was added into the model and constituted a significant change, p < 0.001, in r2 = 0.21. When GPA was added to the hierarchical regression model in the second step, a significant change occurred, p = 0.002, in r2 = 0.33. Both learning methods (B = -3.04, p < 0.001) and prior cumulative GPA (B = 0.41, p < 0.001) were significant predictors of quality points in the hierarchical multiple regression analysis. The simultaneous multiple models accounted for 35.8% of shared variance in quality points (p < 0.001). When adjusted for incoming cumulative GPA, students in the team-based learning course would earn 0.33 more quality points than students in the mixed active-learning course.

Student Opinions: Course Evaluations

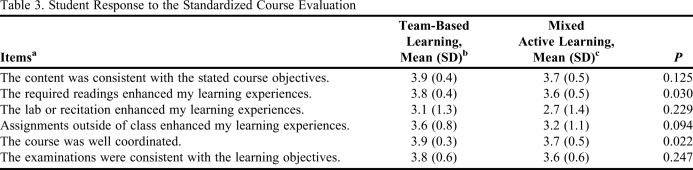

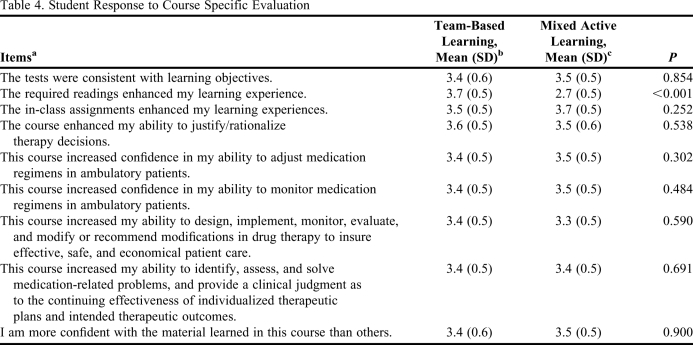

Response rate for the standardized course evaluation was 29 of 37 (team-based learning) and 22 of 27 (mixed active learning), with an overall response rate of 80%. Response rate for the course specific survey instrument was 30 of 37 (team-based learning) and 22 of 27 (mixed active learning), for an overall response rate of 81%. In general, student opinions about both course structures were favorable. Student responses to the standardized course evaluation are listed in Table 3, and responses to the course-specific evaluation are listed in Table 4. Student survey responses were similar for both learning methods, with few exceptions. The standardized course survey result showed a significant difference in student opinion on the usefulness of required readings, and overall course coordination (mean ± SD; team-based learning: 3.8 ± 0.4, mixed active learning: 3.6 ± 0.5, p = 0.03; team-based learning: 3.9 ± 0.3, mixed active learning: 3.7 ± 0.5, p = 0.022).

Table 3.

Student Response to the Standardized Course Evaluation

aRanked on a scale of 1 to 4 on which 1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree.

bn = 29: response rate = 78.4%.

cn = 22: response rate = 81.5%.

Table 4.

Student Response to Course Specific Evaluation

aRanked on a scale of 1 to 4 on which 1 = strongly disagree and 4 = strongly agree.

b n = 30: response rate = 81.1%.

c n = 22: response rate = 81.5%.

Faculty Members' Opinions: Survey of Faculty Members

All 8 faculty members involved in the team-based learning course completed the survey instrument. Seven (88%) thought that team-based learning required less time overall (preparation, implementation, and follow-up/grading) compared with previous small group active-learning experiences. All faculty members indicated that they would consider incorporating team-based learning into other courses they coordinated. The items most frequently cited as challenges to team-based learning included development of team assignments (n = 4), facilitation of class discussions (n = 4), and identification of appropriate required readings (n = 2). The most frequently cited rewards of team-based learning included observation of the students' application of knowledge in the classroom (n = 6), and student team development (n = 3).

DISCUSSION

Pharmacy students have had limited experience applying clinical knowledge prior to their advanced pharmacy practice experiences (APPE). However, active learning can be used to encourage immediate application of knowledge within the classroom. In addition, active learning can be used to develop other skills such as teamwork, communication, and critical thinking. The active-learning method selected should fulfill not only the students' learning requirements, but also be feasible for faculty members to implement.

The active-learning methods compared in this analysis had similar learning objectives and course outcomes, but used different techniques to achieve them. Course structure was the major difference noted between the learning methods. Team-based learning used a structured format that provided elements to assist with guiding students' learning, such as learning objectives for readings, limitations on the length of required readings, maintenance of teams throughout the course, and a similar class structure for each session.

There was a significant difference observed in student performance, with students in the team-based learning course earning more quality points. We relate this difference to the course structure. The essential principles of team-based learning include student accountability for individual and team work, and immediate feedback to correct misconceptions or validate the rationale used. The other factor that may have affected student performance was the difference in evaluation methods used, which is a potential limitation to the study. The mixed active-learning course determined grades based on examinations and student participation, while the team-based learning course used individual and team readiness assurance tests, attendance, and peer evaluations. These formal assessments were comparable (multiple-choice examinations) and weighted similarly to the final course grade. The main difference observed in formal assessments was the quantity and type of content covered by each examination period. In the team-based learning course, each assessment covered 1 topic, and was administered at each class session, whereas the mixed active-learning course assessments covered multiple topics, and were administered as midterm and final examinations. In addition, each course offered a variation of course topics, which altered the material that was included in the formal assessments. This is a limitation of the study, as some students perform more favorably on different types of assessments, and the content covered in each course differed. The team-based learning course included both team and individual assessments. This could have inflated grades in the team-based learning course compared to the mixed active-learning course that used only individual assessment. This is supported by research, which indicates that teams consistently outperform individuals.13 Through the team-based learning process, team members learn from each other, which adds another dimension of learning. Team development and maturation is an important component of team-based and cooperative learning. This process, which can take up to 40 hours of working together, allows students to develop cohesive teams and improves the teams' ability to make optimal choices.6 Others have identified that team-based learning may benefit academically vulnerable students.11-15

Student opinions of both courses were favorable. The main difference observed related to the usefulness of required readings and overall course coordination. Again, we attribute the differences observed to the course structure. The format of team-based learning requires reading objectives to accompany the required readings, and also places limitations on the length of assigned readings. These structural elements provided focused self-directed class preparation, which may have led to student perception of enhanced usefulness of the readings to their overall learning in the course. The favorable response regarding overall course coordination could be attributed to the consistent structure of the team-based learning class sessions. However, in the mixed active-learning course, the structure varied slightly, based on the faculty member facilitating each class session. This difference also may be explained by the method used to create student teams. The mixed active-learning course created new student teams during each class session, while the team-based learning course maintained consistent student teams throughout the course. Team formation has been identified as a key element to team-based learning. Team maintenance allows student relationships to build into a cohesive unit, as the strengths and weaknesses of each member are learned.6

Faculty survey results indicated that the conversion of the course from mixed active- learning to team-based learning required minimal changes in faculty members' workload. The majority of the work was completed prior to the implementation of team-based learning, including the identification of required readings and the development of learning objectives, readiness assurance test questions, and team assignments. Our findings are consistent with survey results of other faculty members who have implemented team-based learning in health sciences education.14 Once the course was implemented, 88 % of faculty members perceived the total amount of time required (preparation, implementation, and follow-up/grading) to conduct a class session using team-based learning is less than that for other small-group learning methods. This is an important finding when evaluating active-learning methods, as most active-learning methods increase faculty members' time, commitment, and resources. The conversion from mixed active- learning to team-based learning also allowed for an increased elective class size to accommodate an expansion in the number of students enrolled in the college. The faculty survey instrument was completed by the study authors and is a limitation to the results. However, the results of the survey were similar to those previously published.14

Both methods of active learning fulfilled all 3 focus areas described by Blouin and colleagues.5 Students were required to obtain factual knowledge prior to each class session. Class time was then used to develop: (1) communication through group and class discussions; (2) critical thinking and problem solving by being presented with challenging patient cases, and; (3) interpersonal skills and teamwork, as the in-class assignments required the student groups to achieve consensus.

Future research evaluating various active-learning methods should assess the impact on students' life-long learning, problem solving, and performance on APPEs. Educational institution-based outcomes should include resource use and economic impact.

CONCLUSION

Student performance, measured by quality points, was significantly higher in the team-based learning course format when adjusted for incoming GPAs. Students were satisfied with both learning models. Team-based learning provided a structured environment to guide pre-class reading assignments, that resulted in favorable student opinions of required readings, compared with other active-learning methods. Faculty members recognized team-based learning as an effective and time-efficient method to conduct small group active learning. Team-based learning and mixed active learning fulfill the focus areas suggested to improve the approach to higher education delivery.

REFERENCES

- 1. Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation Standards and Guidelines for the Professional Program in Pharmacy Leading to the Doctor of Pharmacy Degree. The Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education Inc. http://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/ACPE_Revised_PharmD_Standards_Adopted_Jan152006.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2010.

- 2. Center for the Advancement of Pharmaceutical Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes 2004. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/CAPE2004.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2010.

- 3.Meyers C, Jones TB. Promoting Active Learning: Strategies for the College Classroom. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1993. 14-15;19;79-80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonwell CC, Eison JA. Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. Washington, DC: The George Washington University; 1991. 2,43. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blouin RA, Riffee WH, Robinson ET, et al. AACP curricular change summit supplement: roles of innovation in education delivery. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8) doi: 10.5688/aj7308154. Article 154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michaelsen LK, Parmelee DX, McMahon KK, Levine RE. Team-Based Learning for Health Professions Education. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson BM, Schneider VF, Haidet P, et al. Team-based learning at ten medical schools: two years later. Med Educ. 2007;41(3):250–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koles P, Nelson S, Stolfi A, Parmelee D, DeStephen D. Active learning in a year 2 pathophysiology curriculum. Med Educ. 2005;39(10):1045–1055. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark MC, Nguyen HT, Bray C, Levine RE. Team-based learning in an undergraduate nursing course. J Nurs Educ. 2008;47(3):111–117. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20080301-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haidet P, O'Malley KJ, Richards B. An initial experience with team learning in medical education. Acad Med. 2002;77(1):40–44. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letassy NA, Fugate SE, Medina MS, Stroup JS, Britton ML. Using team-based learning in an endocrine module taught across two campuses. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(5) doi: 10.5688/aj7205103. Article 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beatty SJ, Kelley KA, Metzger AH, Bellebaum KL, McAuley JW. Team-based learning in therapeutics workshop sessions. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(6) doi: 10.5688/aj7306100. Article 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michaelsen LK, Watson WE, Black RH. A realistic test of individual versus group consensus decision making. J Appl Psychol. 1989;4(5):834–839. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson BA, Schneider VF, Haidet P, Perkowski LC, Richards BF. Factors influencing implementation of team-based learning in health sciences education. Acad Med. 2007;82(10 Suppl):S53–S56. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181405f15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conway SE, Johnson LJ, Ripley TL. Integration of team-based learning strategies into a cardiovascular module. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;72(2) doi: 10.5688/aj740235. Article 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]