Abstract

Objective

To design, implement, and assess a rubric to evaluate student presentations in a capstone doctor of pharmacy (PharmD) course.

Design

A 20-item rubric was designed and used to evaluate student presentations in a capstone fourth-year course in 2007-2008, and then revised and expanded to 25 items and used to evaluate student presentations for the same course in 2008-2009. Two faculty members evaluated each presentation.

Assessment

The Many-Facets Rasch Model (MFRM) was used to determine the rubric's reliability, quantify the contribution of evaluator harshness/leniency in scoring, and assess grading validity by comparing the current grading method with a criterion-referenced grading scheme. In 2007-2008, rubric reliability was 0.98, with a separation of 7.1 and 4 rating scale categories. In 2008-2009, MFRM analysis suggested 2 of 98 grades be adjusted to eliminate evaluator leniency, while a further criterion-referenced MFRM analysis suggested 10 of 98 grades should be adjusted.

Conclusion

The evaluation rubric was reliable and evaluator leniency appeared minimal. However, a criterion-referenced re-analysis suggested a need for further revisions to the rubric and evaluation process.

Keywords: assessment, evaluation, reliability, rating scale, criterion-referenced grading, rubric

INTRODUCTION

Evaluations are important in the process of teaching and learning. In health professions education, performance-based evaluations are identified as having “an emphasis on testing complex, ‘higher-order’ knowledge and skills in the real-world context in which they are actually used.”1 Objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) are a common, notable example.2 On Miller's pyramid, a framework used in medical education for measuring learner outcomes, “knows” is placed at the base of the pyramid, followed by “knows how,” then “shows how,” and finally, “does” is placed at the top.3 Based on Miller's pyramid, evaluation formats that use multiple-choice testing focus on “knows” while an OSCE focuses on “shows how.” Just as performance evaluations remain highly valued in medical education,4 authentic task evaluations in pharmacy education may be better indicators of future pharmacist performance.5 Much attention in medical education has been focused on reducing the unreliability of high-stakes evaluations.6 Regardless of educational discipline, high-stakes performance-based evaluations should meet educational standards for reliability and validity.7

PharmD students at University of Toledo College of Pharmacy (UTCP) were required to complete a course on presentations during their final year of pharmacy school and then give a presentation that served as both a capstone experience and a performance-based evaluation for the course. Pharmacists attending the presentations were given Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE)-approved continuing education credits. An evaluation rubric for grading the presentations was designed to allow multiple faculty evaluators to objectively score student performances in the domains of presentation delivery and content. Given the pass/fail grading procedure used in advanced pharmacy practice experiences, passing this presentation-based course and subsequently graduating from pharmacy school were contingent upon this high-stakes evaluation. As a result, the reliability and validity of the rubric used and the evaluation process needed to be closely scrutinized.

Each year, about 100 students completed presentations and at least 40 faculty members served as evaluators. With the use of multiple evaluators, a question of evaluator leniency often arose (ie, whether evaluators used the same criteria for evaluating performances or whether some evaluators graded easier or more harshly than others). At UTCP, opinions among some faculty evaluators and many PharmD students implied that evaluator leniency in judging the students' presentations significantly affected specific students' grades and ultimately their graduation from pharmacy school. While it was plausible that evaluator leniency was occurring, the magnitude of the effect was unknown. Thus, this study was initiated partly to address this concern over grading consistency and scoring variability among evaluators.

Because both students' presentation style and content were deemed important, each item of the rubric was weighted the same across delivery and content. However, because there were more categories related to delivery than content, an additional faculty concern was that students feasibly could present poor content but have an effective presentation delivery and pass the course.

The objectives for this investigation were: (1) to describe and optimize the reliability of the evaluation rubric used in this high-stakes evaluation; (2) to identify the contribution and significance of evaluator leniency to evaluation reliability; and (3) to assess the validity of this evaluation rubric within a criterion-referenced grading paradigm focused on both presentation delivery and content.

DESIGN

The University of Toledo's Institutional Review Board approved this investigation. This study investigated performance evaluation data for an oral presentation course for final-year PharmD students from 2 consecutive academic years (2007-2008 and 2008-2009). The course was taken during the fourth year (P4) of the PharmD program and was a high-stakes, performance-based evaluation. The goal of the course was to serve as a capstone experience, enabling students to demonstrate advanced drug literature evaluation and verbal presentations skills through the development and delivery of a 1-hour presentation. These presentations were to be on a current pharmacy practice topic and of sufficient quality for ACPE-approved continuing education. This experience allowed students to demonstrate their competencies in literature searching, literature evaluation, and application of evidence-based medicine, as well as their oral presentation skills. Students worked closely with a faculty advisor to develop their presentation. Each class (2007-2008 and 2008-2009) was randomly divided, with half of the students taking the course and completing their presentation and evaluation in the fall semester and the other half in the spring semester. To accommodate such a large number of students presenting for 1 hour each, it was necessary to use multiple rooms with presentations taking place concurrently over 2.5 days for both the fall and spring sessions of the course. Two faculty members independently evaluated each student presentation using the provided evaluation rubric. The 2007-2008 presentations involved 104 PharmD students and 40 faculty evaluators, while the 2008-2009 presentations involved 98 students and 46 faculty evaluators.

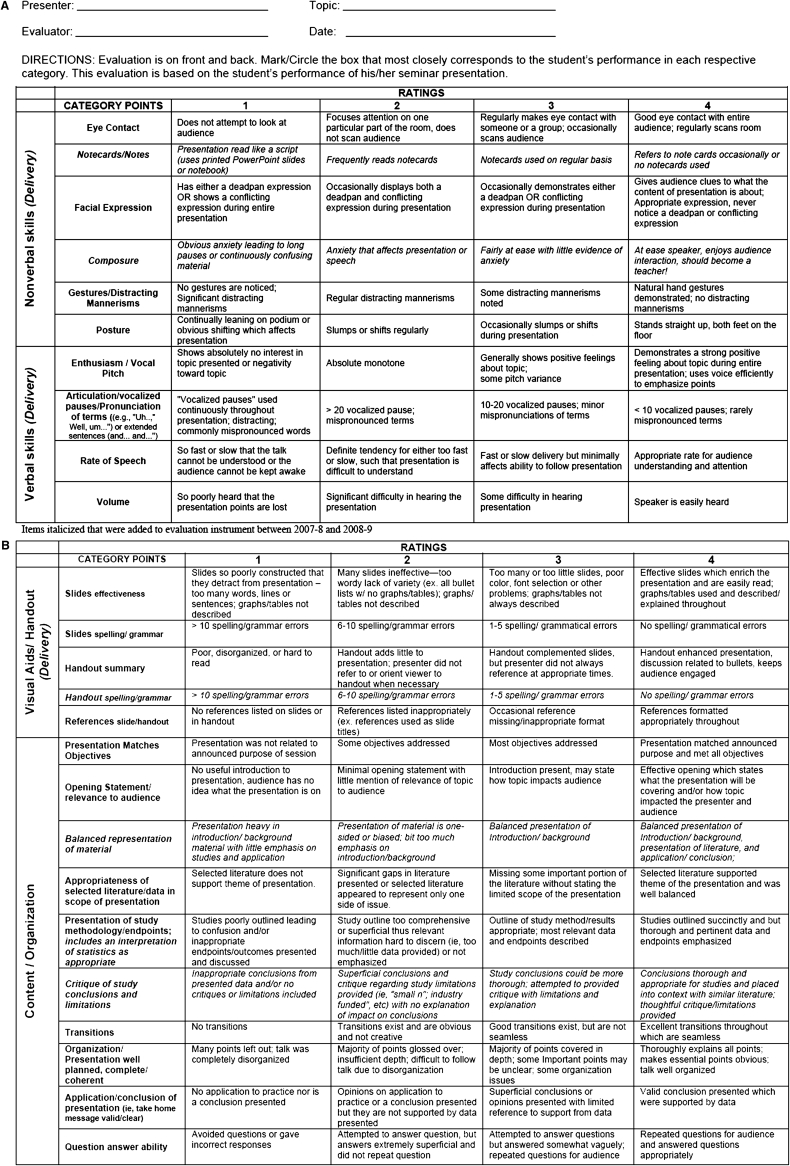

After vetting through the pharmacy practice faculty, the initial rubric used in 2007-2008 focused on describing explicit, specific evaluation criteria such as amounts of eye contact, voice pitch/volume, and descriptions of study methods. The evaluation rubric used in 2008-2009 was similar to the initial rubric, but with 5 items added (Figure 1). The evaluators rated each item (eg, eye contact) based on their perception of the student's performance. The 25 rubric items had equal weight (ie, 4 points each), but each item received a rating from the evaluator of 1 to 4 points. Thus, only 4 rating categories were included as has been recommended in the literature.8 However, some evaluators created an additional 3 rating categories by marking lines in between the 4 ratings to signify half points ie, 1.5, 2.5, and 3.5. For example, for the “notecards/notes” item in Figure 1, a student looked at her notes sporadically during her presentation, but not distractingly nor enough to warrant a score of 3 in the faculty evaluator's opinion, so a 3.5 was given. Thus, a 7-category rating scale (1, 1.5, 2, 2.5. 3, 3.5, and 4) was analyzed. Each independent evaluator's ratings for the 25 items were summed to form a score (0-100%). The 2 evaluators' scores then were averaged and a letter grade was assigned based on the following scale: >90% = A, 80%-89% = B, 70%-79% = C, <70% = F.

Figure 1.

Rubric used to evaluate student presentations given in a 2008-2009 capstone PharmD course.

EVALUATION AND ASSESSMENT

Rubric Reliability

To measure rubric reliability, iterative analyses were performed on the evaluations using the Many-Facets Rasch Model (MFRM) following the 2007-2008 data collection period. While Cronbach's alpha is the most commonly reported coefficient of reliability, its single number reporting without supplementary information can provide incomplete information about reliability.9-11 Due to its formula, Cronbach's alpha can be increased by simply adding more repetitive rubric items or having more rating scale categories, even when no further useful information has been added. The MFRM reports separation, which is calculated differently than Cronbach's alpha, is another source of reliability information. Unlike Cronbach's alpha, separation does not appear enhanced by adding further redundant items. From a measurement perspective, a higher separation value is better than a lower one because students are being divided into meaningful groups after measurement error has been accounted for. Separation can be thought of as the number of units on a ruler where the more units the ruler has, the larger the range of performance levels that can be measured among students. For example, a separation of 4.0 suggests 4 graduations such that a grade of A is distinctly different from a grade of B, which in turn is different from a grade of C or of F. In measuring performances, a separation of 9.0 is better than 5.5, just as a separation of 7.0 is better than a 6.5; a higher separation coefficient suggests that student performance potentially could be divided into a larger number of meaningfully separate groups.

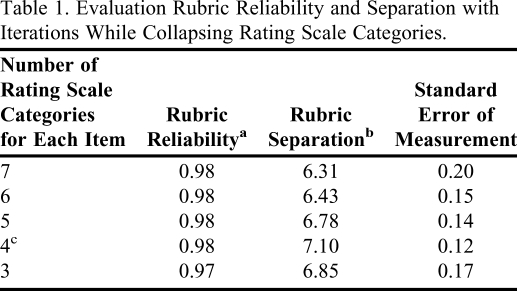

The rating scale can have substantial effects on reliability,8 while description of how a rating scale functions is a unique aspect of the MFRM. With analysis iterations of the 2007-2008 data, the number of rating scale categories were collapsed consecutively until improvements in reliability and/or separation were no longer found. The last positive iteration that led to positive improvements in reliability or separation was deemed an optimal rating scale for this evaluation rubric.

In the 2007-2008 analysis, iterations of the data where run through the MFRM. While only 4 rating scale categories had been included on the rubric, because some faculty members inserted 3 in-between categories, 7 categories had to be included in the analysis. This initial analysis based on a 7-category rubric provided a reliability coefficient (similar to Cronbach's alpha) of 0.98, while the separation coefficient was 6.31. The separation coefficient denoted 6 distinctly separate groups of students based on the items. Rating scale categories were collapsed, with “in-between” categories included in adjacent full-point categories. Table 1 shows the reliability and separation for the iterations as the rating scale was collapsed. As shown, the optimal evaluation rubric maintained a reliability of 0.98, but separation improved the reliability to 7.10 or 7 distinctly separate groups of students based on the items. Another distinctly separate group was added through a reduction in the rating scale while no change was seen to Cronbach's alpha, even though the number of rating scale categories was reduced. Table 1 describes the stepwise, sequential pattern across the final 4 rating scale categories analyzed. Informed by the 2007-2008 results, the 2008-2009 evaluation rubric (Figure 1) used 4 rating scale categories and reliability remained high.

Table 1.

Evaluation Rubric Reliability and Separation with Iterations While Collapsing Rating Scale Categories.

a Reliability coefficient of variance in rater response that is reproducible (ie, Cronbach's alpha).

b Separation is a coefficient of item standard deviation divided by average measurement error and is an additional reliability coefficient.

c Optimal number of rating scale categories based on the highest reliability (0.98) and separation (7.1) values.

Evaluator Leniency

Described by Fleming and colleagues over half a century ago,6 harsh raters (ie, hawks) or lenient raters (ie, doves) have also been demonstrated in more recent studies as an issue as well.12-14 Shortly after 2008-2009 data were collected, those evaluations by multiple faculty evaluators were collated and analyzed in the MFRM to identify possible inconsistent scoring. While traditional interrater reliability does not deal with this issue, the MFRM had been used previously to illustrate evaluator leniency on licensing examinations for medical students and medical residents in the United Kingdom.13 Thus, accounting for evaluator leniency may prove important to grading consistency (and reliability) in a course using multiple evaluators. Along with identifying evaluator leniency, the MFRM also corrected for this variability. For comparison, course grades were calculated by summing the evaluators' actual ratings (as discussed in the Design section) and compared with the MFRM-adjusted grades to quantify the degree of evaluator leniency occurring in this evaluation.

Measures created from the data analysis in the MFRM were converted to percentages using a common linear test-equating procedure involving the mean and standard deviation of the dataset.15 To these percentages, student letter grades were assigned using the same traditional method used in 2007-2008 (ie, 90% = A, 80% - 89% = B, 70% - 79% = C, <70% = F). Letter grades calculated using the revised rubric and the MFRM then were compared to letter grades calculated using the previous rubric and course grading method.

In the analysis of the 2008-2009 data, the interrater reliability for the letter grades when comparing the 2 independent faculty evaluations for each presentation was 0.98 by Cohen's kappa. However, using the 3-facet MRFM revealed significant variation in grading. The interaction of evaluator leniency on student ability and item difficulty was significant, with a chi-square of p < 0.01. As well, the MFRM showed a reliability of 0.77, with a separation of 1.85 (ie, almost 2 groups of evaluators). The MFRM student ability measures were scaled to letter grades and compared with course letter grades. As a result, 2 B's became A's and so evaluator leniency accounted for a 2% change in letter grades (ie, 2 of 98 grades).

Validity and Grading

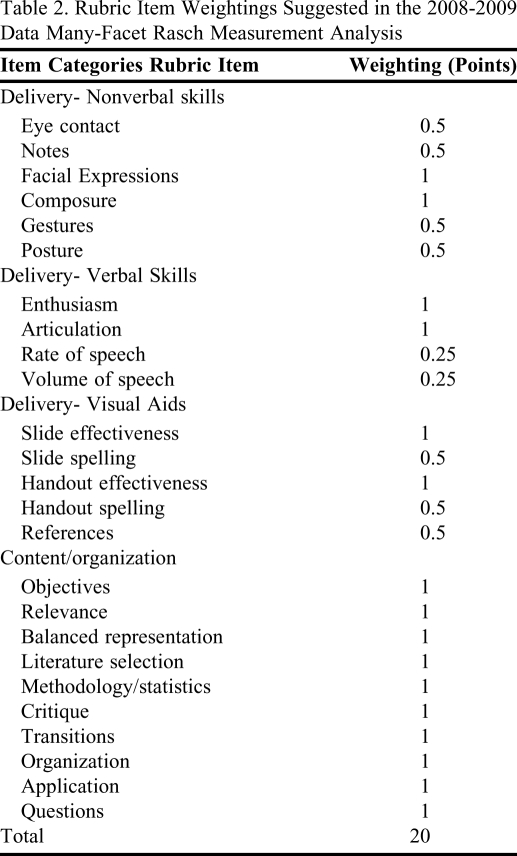

Explicit criterion-referenced standards for grading are recommended for higher evaluation validity.3,16-18 The course coordinator completed 3 additional evaluations of a hypothetical student presentation rating the minimal criteria expected to describe each of an A, B, or C letter grade performance. These evaluations were placed with the other 196 evaluations (2 evaluators × 98 students) from 2008-2009 into the MFRM, with the resulting analysis report giving specific cutoff percentage scores for each letter grade. Unlike the traditional scoring method of assigning all items an equal weight, the MFRM ordered evaluation items from those more difficult for students (given more weight) to those less difficult for students (given less weight). These criterion-referenced letter grades were compared with the grades generated using the traditional grading process.

When the MFRM data were rerun with the criterion-referenced evaluations added into the dataset, a 10% change was seen with letter grades (ie, 10 of 98 grades). When the 10 letter grades were lowered, 1 was below a C, the minimum standard, and suggested a failing performance. Qualitative feedback from faculty evaluators agreed with this suggested criterion-referenced performance failure.

Measurement Model

Within modern test theory, the Rasch Measurement Model maps examinee ability with evaluation item difficulty. Items are not arbitrarily given the same value (ie, 1 point) but vary based on how difficult or easy the items were for examinees. The Rasch measurement model has been used frequently in educational research,19 by numerous high-stakes testing professional bodies such as the National Board of Medical Examiners,20 and also by various state-level departments of education for standardized secondary education examinations.21 The Rasch measurement model itself has rigorous construct validity and reliability.22 A 3-facet MFRM model allows an evaluator variable to be added to the student ability and item difficulty variables that are routine in other Rasch measurement analyses. Just as multiple regression accounts for additional variables in analysis compared to a simple bivariate regression, the MFRM is a multiple variable variant of the Rasch measurement model and was applied in this study using the Facets software (Linacre, Chicago, IL). The MFRM is ideal for performance-based evaluations with the addition of independent evaluator/judges.8,23 From both yearly cohorts in this investigation, evaluation rubric data were collated and placed into the MFRM for separate though subsequent analyses. Within the MFRM output report, a chi-square for a difference in evaluator leniency was reported with an alpha of 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The presentation rubric was reliable. Results from the 2007-2008 analysis illustrated that the number of rating scale categories impacted the reliability of this rubric and that use of only 4 rating scale categories appeared best for measurement. While a 10-point Likert-like scale may commonly be used in patient care settings, such as in quantifying pain, most people cannot process more then 7 points or categories reliably.24 Presumably, when more than 7 categories are used, the categories beyond 7 either are not used or are collapsed by respondents into fewer than 7 categories. Five-point scales commonly are encountered, but use of an odd number of categories can be problematic to interpretation and is not recommended.25 Responses using the middle category could denote a true perceived average or neutral response or responder indecisiveness or even confusion over the question. Therefore, removing the middle category appears advantageous and is supported by our results.

With 2008-2009 data, the MFRM identified evaluator leniency with some evaluators grading more harshly while others were lenient. Evaluator leniency was indeed found in the dataset but only a couple of changes were suggested based on the MFRM-corrected evaluator leniency and did not appear to play a substantial role in the evaluation of this course at this time.

Performance evaluation instruments are either holistic or analytic rubrics.26 The evaluation instrument used in this investigation exemplified an analytic rubric, which elicits specific observations and often demonstrates high reliability. However, Norman and colleagues point out a conundrum where drastically increasing the number of evaluation rubric items (creating something similar to a checklist) could augment a reliability coefficient though it appears to dissociate from that evaluation rubric's validity.27 Validity may be more than the sum of behaviors on evaluation rubric items.28 Having numerous, highly specific evaluation items appears to undermine the rubric's function. With this investigation's evaluation rubric and its numerous items for both presentation style and presentation content, equal numeric weighting of items can in fact allow student presentations to receive a passing score while falling short of the course objectives, as was shown in the present investigation. As opposed to analytic rubrics, holistic rubrics often demonstrate lower yet acceptable reliability, while offering a higher degree of explicit connection to course objectives. A summative, holistic evaluation of presentations may improve validity by allowing expert evaluators to provide their “gut feeling” as experts on whether a performance is “outstanding,” “sufficient,” “borderline,” or “subpar” for dimensions of presentation delivery and content. A holistic rubric that integrates with criteria of the analytic rubric (Figure 1) for evaluators to reflect on but maintains a summary, overall evaluation for each dimension (delivery/content) of the performance, may allow for benefits of each type of rubric to be used advantageously. This finding has been demonstrated with OSCEs in medical education where checklists for completed items (ie, yes/no) at an OSCE station have been successfully replaced with a few reliable global impression rating scales.29-31

Alternatively, and because the MFRM model was used in the current study, an items-weighting approach could be used with the analytic rubric. That is, item weighting based on the difficulty of each rubric item could suggest how many points should be given for that rubric items, eg, some items would be worth 0.25 points, while others would be worth 0.5 points or 1 point (Table 2). As could be expected, the more complex the rubric scoring becomes, the less feasible the rubric is to use. This was the main reason why this revision approach was not chosen by the course coordinator following this study. As well, it does not address the conundrum that the performance may be more than the summation of behavior items in the Figure 1 rubric. This current study cannot suggest which approach would be better as each would have its merits and pitfalls.

Table 2.

Rubric Item Weightings Suggested in the 2008-2009 Data Many-Facet Rasch Measurement Analysis

Regardless of which approach is used, alignment of the evaluation rubric with the course objectives is imperative. Objectivity has been described as a general striving for value-free measurement (ie, free of the evaluator's interests, opinions, preferences, sentiments).27 This is a laudable goal pursued through educational research. Strategies to reduce measurement error, termed objectification, may not necessarily lead to increased objectivity.27 The current investigation suggested that a rubric could become too explicit if all the possible areas of an oral presentation that could be assessed (ie, objectification) were included. This appeared to dilute the effect of important items and lose validity. A holistic rubric that is more straightforward and easier to score quickly may be less likely to lose validity (ie, “lose the forest for the trees”), though operationalizing a revised rubric would need to be investigated further. Similarly, weighting items in an analytic rubric based on their importance and difficulty for students may alleviate this issue; however, adding up individual items might prove arduous. While the rubric in Figure 1, which has evolved over the years, is the subject of ongoing revisions, it appears a reliable rubric on which to build.

The major limitation of this study involves the observational method that was employed. Although the 2 cohorts were from a single institution, investigators did use a completely separate class of PharmD students to verify initial instrument revisions. Optimizing the rubric's rating scale involved collapsing data from misuse of a 4-category rating scale (expanded by evaluators to 7 categories) by a few of the evaluators into 4 independent categories without middle ratings. As a result of the study findings, no actual grading adjustments were made for students in the 2008-2009 presentation course; however, adjustment using the MFRM have been suggested by Roberts and colleagues.13 Since 2008-2009, the course coordinator has made further small revisions to the rubric based on feedback from evaluators, but these have not yet been re-analyzed with the MFRM.

SUMMARY

The evaluation rubric used in this study for student performance evaluations showed high reliability and the data analysis agreed with using 4 rating scale categories to optimize the rubric's reliability. While lenient and harsh faculty evaluators were found, variability in evaluator scoring affected grading in this course only minimally. Aside from reliability, issues of validity were raised using criterion-referenced grading. Future revisions to this evaluation rubric should reflect these criterion-referenced concerns. The rubric analyzed herein appears a suitable starting point for reliable evaluation of PharmD oral presentations, though it has limitations that could be addressed with further attention and revisions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Author contributions— MJP and EGS conceptualized the study, while MJP and GES designed it. MJP, EGS, and GES gave educational content foci for the rubric. As the study statistician, MJP analyzed and interpreted the study data. MJP reviewed the literature and drafted a manuscript. EGS and GES critically reviewed this manuscript and approved the final version for submission. MJP accepts overall responsibility for the accuracy of the data, its analysis, and this report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Swanson DB, Norman GR, Linn RL. Performance-based assessment: lessons from the health professions. Educ Res. 1995;24(5):5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harden RM, Stevenson M, Downie WW, Wilson GM. Assessment of clinical competence using objective structured examination. BMJ. 1975;1(5955):447–451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5955.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med. 1990;65(9):S63–S67. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howley LD. Performance assessment in medical education: where we've been and where we're going. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):285–303. doi: 10.1177/0163278704267044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romanelli F. Pharmacist licensure: time to step it up? Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5) doi: 10.5688/aj740591. Article 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming PR, Manderson WG, Matthews MB, Sanderson PH, Stokes JF. Evolution of an examination: M.R.C.P. (U.K.) BMJ. 1974;2(5910):99–107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5910.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Educational Research Association. Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone MH. Substantive scale construction. J Appl Meas. 2003;4(3):282–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lunz ME, Schumacker RE. Scoring and analysis of performance examinations: a comparison of methods and interpretations. J Outcome Meas. 1997;1(3):219–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(1):98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Streiner DL. Starting at the beginning: an introduction to coefficient alpha and internal consistency. J Pers Assess. 2003;80(1):99–103. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA8001_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iramaneerat C, Yudkowsky R. Rate errors in a clinical skills assessment of medical students. Eval Health Prof. 2007;30(3):266–283. doi: 10.1177/0163278707304040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McManus IC, Thompson M, Mollon J. Assessment of examiner leniency and stringency (‘hawk-dove effect’) in the MRCP(UK) clinical examination (PACES) using multi-facet Rasch modelling. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6 doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-6-42. Article 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts C, Rothnie I, Zoanetti N, Crossley J. Should candidate scores be adjusted for interviewer stringency or leniency in the multiple mini-interview? Med Educ. 2010;44:690–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kolen MJ, Brennan RL. Test Equating. New York NY: Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zlatic TD. Re-visioning Professional Education: An Orientation to Teaching. Kansas City, MO: American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2005. Using assessment to structure learning: putting it all together; pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norcini J. Approaches to standard-setting for performance-based examinations. In: Harden RM, Hart IR, Mulholland H, editors. Approaches to the Assessment of Clinical Competence Part 1. Dundee, Scotland: Centre for Medical Education; 1992. pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stone GE. Objective standard setting (or truth in advertising) J Appl Meas. 2001;2(2):187–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang C, Reeve B. Item response theory and its applications to patient-reported outcome measures. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28:264–282. doi: 10.1177/0163278705278275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downing S. Item-response theory: applications of modern test theory in medical education. Med Educ. 2003;37:739–745. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boone W. Explaining Rasch measurement in different ways. Rasch Measurement Transactions. 2009;23:1198. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EV., Jr Evidence for the reliability of measures and validity of measure interpretation: a Rasch measurement perspective. J Appl Meas. 2001;2(3):281–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linacre JM. Many-Facet Rasch Measurement. Chicago, IL: MESA Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller GA. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol Rev. 1956;63(2):81–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weems GH, Onwuegbuzie AJ. The impact of midpoint responses and reverse coding on survey data. Measure Eval Couns Develop. 2001;34(3):166–176. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RL, Penny JA, Gordon B. Assessing Performance: Designing, Scoring, and Validating Performance Tasks. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman GR, Van der Vleuten CPM, De Graaff E. Pitfalls in the pursuit of objectivity: issues of validity, efficiency and acceptability. Med Educ. 1991;25:119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1991.tb00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use. 4th ed. New York NY: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regehr G, MacRae H, Reznick RK, Szalay D. Comparing the psychometric properties of checklists and global rating scales for assessing performance on an OSCE-format examination. Acad Med. 1998;73(9):993–997. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199809000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodges B, Regehr G, McNaughton N, Tiberius R, Hanson M. OSCE checklists do not capture increasing levels of expertise. Acad Med. 1999;74(10):1129–1134. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199910000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodges B, McIlroy JH. Analytic global OSCE ratings are sensitive to levels of training. Med Educ. 2003;37(11):1012–1016. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]