Abstract

Despite various lines of evidence pointing to the compartmentation of metabolism within the brain, few studies have reported the effect of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) on neuronal and astrocyte compartments and/or metabolic trafficking between these cells. In this study we used ex vivo 13C NMR spectroscopy following an infusion of [1-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C2] acetate to study oxidative metabolism in neurons and astrocytes of sham-operated and fluid percussion brain injured (FPI) rats at 1, 5, and 14 days post-surgery. FPI resulted in a decrease in the 13C glucose enrichment of glutamate in neurons in the injured hemisphere at day 1. In contrast, enrichment of glutamine in astrocytes from acetate was not significantly decreased at day 1. At day 5 the 13C enrichment of glutamate and glutamine from glucose in the injured hemisphere of FPI rats did not differ from sham levels, but glutamine derived from acetate metabolism in astrocytes was significantly increased. The 13C glucose enrichment of the C3 position of glutamate (C3) in neurons was significantly decreased ipsilateral to FPI at day 14, whereas the enrichment of glutamine in astrocytes had returned to sham levels at this time point. These findings indicate that the oxidative metabolism of glucose is reduced to a greater extent in neurons compared to astrocytes following a FPI. The increased utilization of acetate to synthesize glutamine, and the acetate enrichment of glutamate via the glutamate-glutamine cycle, suggests an integral protective role for astrocytes in maintaining metabolic function following TBI-induced impairments in glucose metabolism.

Key words: astrocyte, compartmentation, fluid percussion injury, glutamate, glutamine, neuron

Introduction

Neurons and astrocytes are heavily dependent upon glucose (Glc) as a metabolic substrate for energy metabolism, amino acid synthesis, and neurotransmission. Astrocytes play a pivotal role in meeting the energy requirements of neurons, as the net synthesis of glutamate (Glu) requires a flux of tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates, notably glutamine (Gln), from astrocytes (Schousboe et al., 1997). In addition, the net synthesis of Gln depends upon the entry of pyruvate via an anaplerotic pathway into the TCA cycle, which is exclusively achieved by pyruvate carboxylase (PC; IUBMB enzyme nomenclature EC 6.4.1.1), an astrocyte-specific enzyme (Shank et al., 1985; Yu et al., 1983).

During neurotransmission the glutamate-glutamine (Glu-Gln) cycle links the exchange of Glu and Gln between cell types. In this cycle, astrocytes remove excess Glu from the synaptic cleft and convert Glu to Gln via glutamine synthetase (EC 6.3.1.2). Gln that is released from astrocytes can then be taken up by neurons, thereby recycling Glu and replacing carbon skeletons lost during neurotransmission (van den Berg and Garfinkel, 1971; van den Berg et al., 1969). The Glu-Gln cycle is an open pathway whereby the metabolism of both Glu and Gln interact with numerous metabolic pathways, depending on the metabolic needs of the cell, and whether Glu is exogenously taken up from the extracellular environment, or formed endogenously via glutaminase (EC 3.5.1.2; reviewed in McKenna, 2007).

One consequence of traumatic brain injury (TBI) is an alteration in the uptake of glucose and oxidative metabolism. Dynamic measurements of glucose metabolism using 18F fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in humans, and/or 2-deoxyglucose autoradiography in rats, has shown a brief, acute increase in the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose (CMRglc; Bergsneider et al., 1997, 2000, 2001; Yoshino et al., 1991). During this period of increased glucose uptake, there is a concomitant decrease in extracellular glucose concentration as measured by cerebral microdialysis in humans (Vespa et al., 2003, 2006) and rats (Fukushima et al., 2009). In the lateral FPI model, the acute increase in CMRglc is followed by a prolonged period of reduced CMRglc beginning by 6 h post-injury, which then recovers to baseline within 10 days post-injury (Moore et al., 2000; Yoshino et al., 1991). The time course of reduced CMRglc corresponds to the time course of reductions in cytochrome oxidase activity (Harris et al., 2001; Hovda et al., 1991). These findings suggest a prolonged period of reduced glucose oxidative metabolism, which represents a period of metabolic vulnerability during which cells may be unable to withstand further injury.

Knowledge regarding the metabolic changes in specific cell types, and/or in the trafficking of metabolites between cells is critical for designing successful therapies that bypass metabolic dysfunction or take advantage of cell-specific metabolic capacities. In the current study we used [1,2-13C2] acetate as an astrocyte-specific metabolic substrate in conjunction with [1-13C] glucose, the primary metabolic substrate for neurons and astrocytes, to determine if both neurons and astrocytes contribute to the previously observed reduction in oxidative metabolism during the hypometabolic period following a lateral fluid percussion injury (FPI).

Methods

Experimental groups

The UCLA Chancellor's Committee for Animal Research approved all experimental procedures used in this study. Fifteen male Sprague-Dawley rats (280–320 g) were randomly assigned to the FPI groups for post-surgery studies on days 1, 5, or 14 (n = 5/group). An additional 12 male rats were randomly assigned to sham-injury groups for studies on days 1, 5, or 14 (n = 4/group).

Surgical procedures

Surgical anesthesia was induced in the rats using isofluorane inhalation. A moderate FPI (2.25 atm) was induced via a 3-mm-diameter craniotomy centered at –3.0 mm from the bregma and 6.0 mm lateral to the midline over the left cerebral cortex, following previously published protocols (Osteen et al., 2004; Prins et al., 1996). Briefly, a plastic injury cap was secured over the craniotomy with cyanoacrylate and dental acrylic. Once the acrylic completely hardened, this injury cap was filled with sterile 0.9% saline after removing the animal from the stereotaxic frame. Anesthesia was removed and the animal was connected to the FP device. FPI was induced immediately after the animal exhibited a pedal/withdrawal reflex of the hindlimb. The duration of injury-induced unconsciousness (loss of the pedal reflex) and apnea were recorded for each animal. Anesthesia was reinstated immediately upon recovery of the pedal/withdrawal reflex of the hindlimb, the injury cap was removed, the craniotomy site was covered with saline-moistened surgical foam, and the scalp was sutured. Sham-injury rats were anesthetized for a similar duration, with sham animals receiving a 3-mm craniotomy only. The rectal temperature was monitored throughout all surgical procedures and maintained at 37.0–38.0°C using a thermostatically controlled heating pad (Harvard Apparatus Limited, Edenbridge, KY). At the end of surgery bupivacaine (0.25%) was locally infiltrated into the cranial incision site and the animals were placed in a warm cage (36.0–38.0°C) until recovery from anesthesia, at which time they were returned to their home cages.

[1-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C2] acetate infusion

Animals in the sham-injury or FPI groups (at 1, 5, or 14 days post-injury) were anesthetized and the right femoral artery and vein were cannulated with PE 50 tubing. The scalp was reopened and washed with saline, and the dorsal skull surface, including the craniotomy site in sham-injury and FPI animals, was covered with dental acrylic. This layer of dental acrylic over the cranial defect was found to be necessary to prevent overheating and herniation of the left cortex through the craniotomy during microwave irradiation. Bupivacaine (0.25%) was locally infiltrated into the femoral and cranial incision sites, and the animals were restrained on a cardboard plank prior to removing anesthesia. Labeled substrate infusion into the femoral vein was initiated 30 min after the termination of surgical anesthesia, so the animals were fully awake during the infusion. The infusion protocol, modified from our previous publication (Bartnik et al., 2007b), began with a bolus injection of 225 mmol of [1-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C2] acetate (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA), followed by 150 mmol given in exponentially decreasing amounts over the next 8 min, until a final constant infusion rate of 1.0 mmol/h was reached and maintained for 1 h. At the end of the infusion, the animals were rapidly anesthetized with isofluorane and euthanized by a focused microwave beam to the head (1.8 kW for 6.25 sec) using a Metabostat microwave (Thermex-Thermatron, Louisville, KY). Following euthanasia the brain was removed, and the cerebellum and brainstem were removed and discarded. The forebrain was dissected into left (ipsilateral to injury) and right (contralateral) hemispheres, and frozen at –70°C until processed for NMR spectroscopy.

Blood sampling

Arterial blood samples were taken prior to and just before the end of the substrate infusion to determine Po2, Pco2, and pH (238 pH/Blood Gas Analyzer; Ciba Corning Diagnostics Ltd., Halstead, England). Pre-infusion and post-infusion plasma total (12C + 13C) glucose and lactate concentrations were measured using an YSI 2700 Select Biochemistry Analyzer (YSI Life Sciences, Yellow Springs, OH). An additional post-infusion arterial blood sample for measuring the plasma 13C-labeled glucose, acetate, and lactate concentrations was immediately centrifuged (14,000 rpm for 5 min), and the plasma was frozen at –70°C until prepared for 13C NMR spectroscopy.

Metabolite extraction and sample preparation

The frozen plasma and left and right hemisphere tissue samples were homogenized in 8% cold perchloric acid (Sonic Dismembrator; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). After centrifugation (14,000g for 20 min), the supernatant was neutralized with 5 N KOH, centrifuged again to remove the perchloric salts, and lyophilized to dryness. Tissue pellets were solubilized in 1 mL of 1 N NaOH and the protein content was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA), on a SPECTRAmax 190 microplate spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) at a wavelength of 595 nm.

NMR spectroscopy

Prior to NMR spectroscopy the lyophilized samples were re-suspended in 0.5 mL of D2O (99.9% D) containing 0.075% by weight sodium 3-(trimethylsilyl) propionate (TSP), and the pH was adjusted to neutral (7.0–7.2). 13C and fully relaxed 1H NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker AM 360 MHz spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsrough, Germany). 13C spectra were acquired using a 4.1-μsec pulse width, 1.2-sec acquisition time, and a 3-sec recycle delay. Waltz16 broad band decoupling was used during the acquisition of the 13C spectra to avoid nuclear Overhauser enhancement effects. The number of acquisitions was typically 14,000–15,000. Fully relaxed 1H spectra were acquired using the Bruker AM spectrometer operating at 600 MHz using a pulse angle of 70°, 8-sec acquisition time, 10-sec repetition time, 7-KHz spectral width, and 1.2-μsec water preset soft pulse. The number of acquisitions was 256 scans.

Metabolite enrichment

Chemical shifts of both 1H and 13C peaks were assigned relative to TSP and by comparison to previously published values (Cruz and Cerdan, 1999; Govindaraju et al., 2000). All peaks were integrated, quantified using TSP as an internal standard (Badar-Goffer et al., 1990), and normalized to the total protein content of each sample. The total amount of tissue and plasma glucose (Glc), acetate (Ac), Glu, Gln, and lactate (Lac) were quantified using the 1H NMR analysis. The percent 13C enrichment of each isotopomer was calculated using the formula:

|

where 13C [M] is the normalized 13C concentration of the metabolite isotopomer (M), 1H [M] is the normalized 1H concentration of the total metabolite pool, and 1.1% is the percentage of naturally abundant 13C.

Acetate:glucose utilization ratio

The acetate:glucose (Ac:Glc) utilization ratio for Glu and Gln (Glx) synthesis was determined according to the method of Taylor and associates (1996) using the formula:

|

where Glx C3,4 corresponds to the 13C enrichment of the Glu or Gln C4 doublet from [1,2-13C2] acetate, and Glx C4 is the 13C enrichment of the Glu or Gln C4 singlet resulting from [1-13C] glucose.

Relative contribution of glucose and acetate to Glu and Gln synthesis

The relative contribution of glucose to Glu or Gln synthesis was calculated from the Glu and Gln C4 enrichment according to the method of Serres and colleagues (2007, 2008). Glucose contribution (α) was calculated using the formula:

|

where {Glx C4} is the 13C enrichment of Glu or Gln C4, {Glc C1} is the 13C enrichment of brain Glc C1, and 1.1 is the percent natural abundance of 13C in the brain. The relative contribution of acetate (β) to Glu and Gln C4 enrichment from [1,2-13C2] acetate can also be calculated using the formula:

|

where {Glc C1}and {Glc C6} are the 13C enrichment of Glc C1 and C6 through hepatic gluconeogenesis, and {Ac C2} is the 13C enrichment of plasma Ac C2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v. 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Between-group differences in the duration of apnea and unconsciousness (in seconds), and the pre- and post-infusion physiological measures (group means ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) were determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons. Frequency analysis showed that not all tissue isotopomers had a normal gaussian distribution, thus between-group differences were determined using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis, with Mann-Whitney post-hoc comparisons after data conversion to median and interquartile range. For descriptive purposes all data were expressed as group means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analysis of the tissue isotopomers was limited to the Glu and Gln isotopomers, reflecting the synthesis of amino acids from glucose in the neuronal TCA cycle via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and the metabolism of glucose and acetate in the astrocyte TCA cycle via PDH, PC, and acetyl-CoA synthetase (acetate-CoA ligase; EC 6.2.1.1), respectively.

Results

Injury and physiological measures

There were no significant differences in the duration (mean ± SD) of injury-induced unconsciousness between FPI rats assigned to the day 1 (170.20 ± 81.89 sec), day 5 (158.80 ± 40.18 sec), or day 14 (150.00 ± 51.96 sec) study groups. Mild injury-induced apnea was observed in all FPI animals. The duration of apnea in the day 14 FPI group (13.50 ± 2.59 sec) was significantly (p < 0.05) longer than apnea in the day 1 FPI group (9.00 ± 2.55 sec), but apnea duration in both of these groups did not differ from the day 5 FPI group (10.40 ± 2.19 sec).

Table 1 shows the pH, Pco2, Po2, and the plasma glucose and lactate concentrations in the experimental groups before and after the infusion of [1-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C2] acetate. There was no difference in the physiological measures between day 1, 5, and 14 sham-injured animals, therefore these animals were combined into a single sham group for comparison to the FPI groups. There were no differences in the pre- or post-infusion physiological measures, or in the plasma total glucose and total lactate concentration between groups.

Table 1.

Physiological Measurements and Total Plasma Glucose and Lactate Concentrations in Sham and FPI Rats Before and After Substrate Infusion

| |

Sham (n = 12) |

1 Day post-FPI (n = 5) |

5 Days post-FPI (n = 5) |

14 Days post-FPI (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-infusion | Post-infusion | Pre-infusion | Post-infusion | Pre-infusion | Post-infusion | Pre-infusion | Post-infusion | |

| pH | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 7.5 ± 0.01 | 7.4 ± 0.02 | 7.6 ± 0.01 | 7.4 ± 0.03 | 7.5 ± 0.01 | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 7.5 ± 0.02 |

| Pco2 | 37.0 ± 0.80 | 36.8 ± 0.98 | 42.4 ± 2.66 | 38.8 ± 1.56 | 40.2 ± 5.39 | 37.8 ± 0.97 | 36.8 ± 1.05 | 37.5 ± 1.28 |

| Po2 | 91.0 ± 2.37 | 91.6 ± 1.32 | 80.8 ± 6.03 | 83.0 ± 4.00 | 87.6 ± 9.04 | 86.4 ± 3.60 | 94.0 ± 4.77 | 89.0 ± 4.28 |

| Glucose | 11.1 ± 0.66 | 11.8 ± 1.41 | 11.8 ± 2.14 | 15.5 ± 4.67 | 13.0 ± 1.20 | 14.8 ± 2.27 | 10.4 ± 0.55 | 14.2 ± 1.63 |

| Lactate | 2.10 ± 0.48 | 1.77 ± 0.36 | 1.53 ± 0.50 | 1.39 ± 0.44 | 4.0 ± 1.81 | 1.54 ± 0.15 | 1.96 ± 0.62 | 2.04 ± 0.62 |

FPI, fluid percussion injury. Pco2 and Po2 (mm Hg) are the partial pressure of CO2 and O2, respectively. Plasma glucose and lactate are expressed as mmol/L. All values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

NMR analysis

Plasma

NMR spectra of the plasma samples taken from all groups showed 13C-labeled glucose (Glc) C1 α and β anomer singlet resonances, a lactate (Lac) C3 singlet originating from 13C glucose metabolism, and an acetate (Ac) C2 doublet resonance (spectra not shown). No differences for any plasma isotopomers were found between day 1, 5, and 14 sham-injured animals, so the data were pooled to form a single sham-injury control group. The Glc C1 percent enrichment reached 59.1 ± 7.4% in the sham-injury group, and enrichment in the FPI groups was 42.5 ± 8.2% at day 1, 52.0 ± 12.1% at day 5, and 48.9 ± 7.4% at day 14 following the 60 min infusion. Doublet resonances of 13C glucose were not observed in any of the plasma samples, indicating that our infusion protocol did not result in any detectable labeling of glucose from [1,2-13C2] acetate, and that the peripheral conversion of acetate to glucose did not contribute to the labeling of cerebral amino acids. The Ac C2 percent 13C enrichment of plasma acetate reached 60.1 ± 4.5%, 52.6 ± 9.6%, 53.9 ± 3.8%, and 54.6 ± 3.5% in the sham, day 1, day 5, and day 14 groups, respectively, following the 60-min infusion. The enrichment of Lac C2 was 24.2 ± 8.02%, 28.0 ± 9.6%, 23.9 ± 11.7%, and 20.8 ± 11.7% in the sham, day 1, day 5, and day 14 groups, respectively. There were no significant group differences in the 13C enrichment of plasma Glc, Ac, or Lac between study groups, indicating that differences in brain metabolite enrichment were not the result of injury-induced changes in peripheral metabolism.

Brain tissue

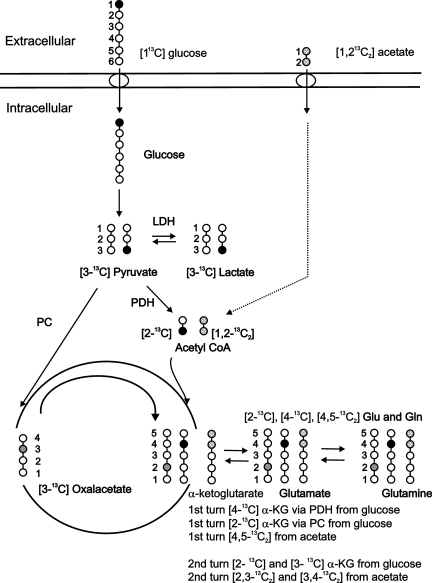

Figure 1 illustrates the metabolism of [1-13C] glucose in both neurons and astrocytes, and the metabolism of [1,2-13C2] acetate in astrocytes. Glycolysis of [1-13C] glucose in both cell types results in the formation of [3-13C] pyruvate. Before entering the TCA cycle [3-13C] pyruvate is decarboxylated to [2-13C] acetyl CoA via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH; EC 1.2.4.1). In astrocytes [3-13C] pyruvate can also be transformed to [3-13C] oxaloacetate (OAA) via pyruvate carboxylase (PC). Oxidative metabolism of glucose in the first turn of the TCA cycle in neurons results in the synthesis of a singlet [4-13C] Glu isotopomer resonance (C4s). In astrocytes, the oxidative metabolism of glucose in the first turn of the TCA cycle results in the synthesis of a [4-13C] Gln (C4s) singlet from metabolism via PDH, and a [2-13C] Gln (C2s) singlet from metabolism via PC. 13C carbon skeletons that remain in the TCA cycle of both cell types are equally divided between [2-13C] and [3-13C] succinate, and appear as C2s and C3s Glu and Gln singlet resonances in neurons and astrocytes, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the metabolism of [1-13C] glucose in neurons and astrocytes, and [1,2-13C2] acetate in astrocytes. The metabolism of [1-13C] glucose and entry of pyruvate into the TCA cycle via pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) is indicated by the solid black circles. The entry of pyruvate into the TCA cycle via pyruvate carboxylase (PC) is indicated by the solid grey circles. The metabolism of [1,2-13C2] acetate is indicated by the hatched circles. See text for details (α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine).

Metabolism in the astrocyte compartment can also be studied using 13C acetate as a substrate (van den Berg et al., 1969), due to the presence of a specific acetate uptake mechanism (Waniewski and Martin, 1998). In astrocytes [1,2-13C2] acetate is metabolized to [1,2-13C2] acetyl CoA, with oxidation in the first turn of the TCA cycle resulting in the synthesis of Gln carrying a 13C label in the fourth and fifth carbon positions ([4,5-13C2] Gln doublet; C4d; Fig. 1). 13C carbon skeletons that remain in the astrocyte TCA cycle past the first turn appear as Gln C2d and C3d doublet resonances (Sonnewald and Kondziella, 2003).

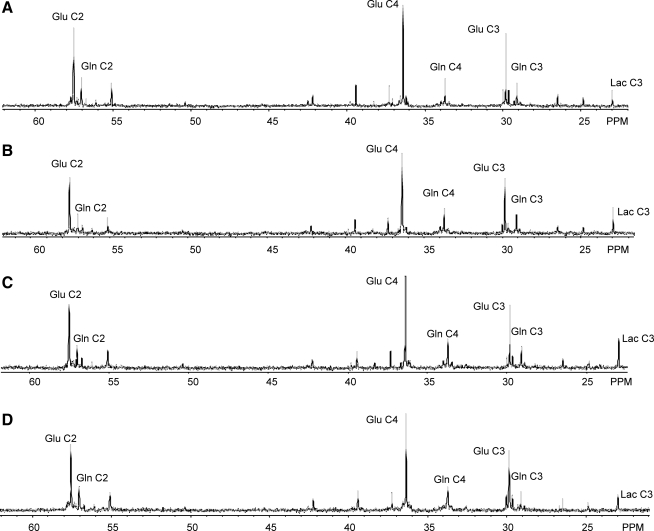

The glutamate-glutamine (Glu-Gln) cycle functions to metabolically link neurons and astrocytes via the rapid exchange of neuronal Glu with astrocyte Gln (Daikhin and Yudkoff, 2000; van den Berg and Garfinkel, 1971). In this cycle, 13C Glu release by neurons during synaptic transmission can be taken up by astrocytes and converted to 13C Gln via the astrocyte-specific enzyme glutamine synthetase (EC 1.4.1.14; Norenberg and Martinez-Hernandez, 1979). In return, 13C Gln synthesized from glucose oxidation in astrocytes or via glutamine synthetase can be released and taken up by neurons and converted to 13C Glu via phosphate activated glutaminase (EC 3.5.1.2) or (re-) introduced into the neuron TCA cycle as α-ketoglutarate via glutamate dehydrogenase (EC 1.4.1.3; Shokati et al., 2005). Figure 2 shows representative spectra from the left/injured hemisphere following the infusion of [1-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C2] acetate in the sham (A), day 1 (B), day 5 (C), and day 14 (D) post-FPI groups. Metabolites synthesized from [1-13C] glucose included Lac, Glu, and Gln singlet (s) resonances, whereas doublet (d) resonances of Glu and Gln were derived from the metabolism of [1,2-13C2] acetate.

FIG. 2.

Representative ex vivo 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra from extracts of the left/injured cortex of sham (A), day 1 (B), day 5 (C), and day 14 (D) post-FPI groups. Spectra were acquired from the left/injured hemisphere and scaled to the internal reference (not shown; Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine; Lac, lactate; FPI, fluid percussion injury).

Metabolite enrichment

Table 2 summarizes the percent 13C enrichment of the Glu and Gln isotopomers synthesized from [1-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C2] acetate, in the left/injured and right hemispheres of the animals in the experimental groups. Between-group comparisons of the sham-injury animals using one-way ANOVAs showed no difference in brain metabolite enrichment between the day 1, day 5, and day 14 groups, thus these animals were combined into a single sham group for all comparisons to the FPI groups.

Table 2.

Percent13C Enrichment in Sham and FPI Rats as Measured by13C NMR Spectroscopy

| |

Sham (n = 12) |

FPI 1 day (n = 5) |

FPI 5 day (n = 5) |

FPI 14 day (n = 5) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolite | Left | Right | Left/injured | Right | Left/injured | Right | Left/injured | Right |

| Gln C2s | 13.38 ± 5.97 | 12.31 ± 2.39 | 7.84 ± 4.17 | 10.90 ± 2.84 | 14.70 ± 4.77 | 12.94 ± 4.69 | 9.58 ± 5.58 | 8.84 ± 2.79 |

| Gln C2d | 9.26 ± 3.30 | 11.60 ± 2.99 | 9.66 ± 3.49 | 11.60 ± 3.81 | 16.20 ± 4.37*a b | 9.16 ± 2.80 | 11.32 ± 2.74 | 10.28 ± 3.67 |

| Gln C3s | 10.85 ± 3.94 | 6.85 ± 1.78 | 6.92 ± 3.28 | 8.32 ± 1.87 | 9.64 ± 3.39 | 10.26 ± 3.85*b | 8.36 ± 3.62 | 5.40 ± 1.56*c |

| Gln C3d | 3.82 ± 1.55 | 2.83 ± 0.89 | 6.86 ± 1.46 | 3.90 ± 1.91 | 9.12 ± 2.49 | 3.72 ± 1.70 | 7.61 ± 2.66 | 2.58 ± 0.89 |

| Gln C4s | 17.33 ± 4.96 | 14.39 ± 6.47 | 10.92 ± 4.06*a | 14.08 ± 4.52 | 11.96 ± 3.99 | 11.08 ± 2.17 | 19.78 ± 5.59*bc | 16.74 ± 5.43 |

| Gln C4d | 9.73 ± 3.28 | 7.29 ± 3.14 | 12.88 ± 5.97 | 7.72 ± 2.13 | 8.76 ± 4.02 | 6.04 ± 2.08 | 11.70 ± 2.42 | 9.82 ± 2.85 |

| Glu C2s | 20.72 ± 6.41 | 15.70 ± 4.17 | 9.98 ± 4.32*a | 16.78 ± 4.74# | 15.62 ± 3.98 | 15.04 ± 3.25 | 14.74 ± 6.25 | 8.80 ± 4.35*b |

| Glu C2d | 10.41 ± 3.51 | 9.91 ± 3.04 | 5.86 ± 2.01*a | 9.42 ± 2.44 | 6.46 ± 2.52 | 9.52 ± 3.25 | 12.48 ± 2.74*bc | 9.52 ± 3.01 |

| Glu C3s | 14.30 ± 4.15 | 11.24 ± 4.62 | 9.28 ± 3.80 | 11.80 ± 1.87 | 10.64 ± 1.13*a | 12.20 ± 3.14 | 8.58 ± 1.70*a | 7.52 ± 3.31 |

| Glu C3d | 7.79 ± 2.26 | 7.33 ± 3.23 | 4.62 ± 1.89*a | 7.74 ± 2.92 | 6.04 ± 1.88 | 8.26 ± 3.71 | 5.76 ± 2.15 | 4.64 ± 2.23 |

| Glu C4s | 24.79 ± 6.01 | 23.64 ± 7.67 | 11.20 ± 2.63*a | 19.76 ± 2.95# | 18.44 ± 1.54*b | 19.02 ± 3.74 | 17.60 ± 3.26*b | 21.62 ± 6.63 |

| Glu C4d | 9.87 ± 3.44 | 9.90 ± 4.43 | 7.12 ± 3.00 | 11.04 ± 1.54 | 7.54 ± 1.65 | 8.84 ± 2.43 | 11.20 ± 2.64*b | 7.74 ± 2.28# |

p < 0.05 compared to the same hemisphere of the shams (a), 1 day post-FPI group (b), and/or 5 day post-FPI group (c).

p < 0.05 compared to the injured hemisphere (within-group effect).

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, with values in bold type denoting statistical significance. Between-group differences were measured using non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis.

FPI, fluid percussion injury; Lac, lactate; Gln, glutamine; Glu, glutamate; s, singlet resonance originating from the metabolism of [1-13C] glucose; d, doublet resonance originating from the metabolism of [1,2-13C2] acetate.

At day 1 post-FPI, the [1-13C] glucose enrichment of Glu C4s and Glu C2s from metabolism predominantly in neurons was significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere compared to the left hemisphere of the sham group (Table 2). This finding suggests reduced oxidative metabolism and amino acid synthesis in neurons of the injured hemisphere. In addition, the enrichment of Gln C4s from [1-13C] glucose was significantly reduced (p < 0.05), which suggests reduced oxidative metabolism of glucose in astrocytes at day 1 post-FPI. In contrast, the [1,2-13C2] acetate enrichment of Gln C4, C2, and C3 in astrocytes was not significantly affected in the left/injured hemisphere of day 1 FPI animals compared to sham animals, indicating ongoing oxidative metabolism of acetate in astrocytes. Via the Glu-Gln cycle, the [1,2-13C2] acetate enrichment of Glu C3d and Glu C2d in the left/injured hemisphere was significantly lower (p < 0.05) at day 1 post-FPI compared to sham animals. Comparisons between hemispheres at day 1 post-FPI indicated that glucose enrichment of Glu C4s and Glu C2s in neurons, the glucose enrichment of Gln C2s in astrocytes, and the acetate enrichment of Glu C2d via the Glu-Gln cycle, were significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere compared to the right hemisphere at day 1.

At day 5 post-FPI the glucose enrichment of Glu C3s from metabolism in neurons within the left/injured hemisphere was significantly decreased (p < 0.05) compared to sham animals (Table 2). However, the glucose enrichment of Glu C4s was significantly increased (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere at day 5 compared to the day 1 FPI group, suggesting some recovery of neuronal glucose metabolism. A significant increase (p < 0.05) in the [1,2-13C2] acetate enrichment of Gln C2d in astrocytes was also seen in the left/injured hemisphere of the day 5 FPI animals compared to the sham and day 1 FPI groups. In the right hemisphere, the enrichment of Gln C3s from the cycling of 13C-labeled glucose carbons in astrocytes was significantly increased (p < 0.05) compared to the right hemisphere of sham animals (Table 2). There were no differences between hemispheres in the Glu or Gln enrichment from either glucose or acetate at day 5 post-FPI.

On day 14 post-FPI the Glu C3s enrichment from the cycling of 13C-labeled carbons in the neuronal TCA cycle remained significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere compared to the left hemisphere of the sham group (Table 2). The [1-13C] glucose enrichment of Gln C4s in the first turn of the astrocyte TCA cycle was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere at day 14 compared to both day 1 and day 5 post-FPI. Similarly, the [1-13C] glucose enrichment of Glu C4s in the first turn of the neuron TCA cycle was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere at day 14 compared to day 1 post-FPI. The [1,2-13C2] acetate enrichment of Glu C2d via the Glu-Gln cycle was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere at day 14 compared to days 1 and 5 post-injury. In addition, the [1,2-13C2] acetate enrichment of Glu C4d via the Glu-Gln cycle was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the left/injured hemisphere on day 14 than at day 1 post-injury. These effects indicate the recovery of metabolic processes as isotopomer levels are similar to shams and show improvement compared to the day 1 and day 5 groups. In the right hemisphere, the enrichment of Glu C2s and Gln C3s from glucose at day 14 was significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared to day 1, and Gln C3s was significantly lower (p < 0.05) compared to day 5 post-FPI (Table 2). Comparisons between the two hemispheres of the FPI group showed that the acetate enrichment of Glu C4d via the Glu-Gln cycle was significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the left/injured compared to the right hemisphere at day 14.

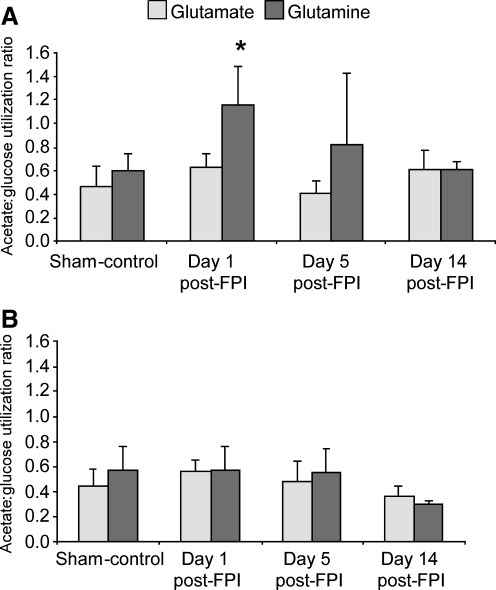

Acetate:glucose utilization ratio

Figure 3 shows the acetate:glucose (Ac:Glc) utilization ratio for the synthesis of Gln C4 and Glu C4 in the first turn of the astrocyte and neuron TCA cycles, respectively. A significant increase (p < 0.05) in the Ac:Glc utilization ratio for Gln was observed in the left/injured hemisphere at day 1 post-FPI (Fig. 3A). Although not significant (p = 0.11), this ratio was also increased for Gln at day 5 post-FPI. This finding suggests that there is a greater utilization of acetate, a decrease in glucose utilization, or a combination of both, in the astrocyte compartment at day 1 post-FPI (Table 2). In contrast, the Ac:Glc utilization ratio for Glu synthesis in the left/injured hemisphere did not differ between the sham and the post-FPI groups at any time point (Fig. 3A). Since the glucose enrichment of Glu was decreased at day 1 post-FPI, the metabolism of [1,2-13C2]-labeled Gln to Glu via phosphate-activated glutaminase activity in the neurons would also have to be decreased at day 1 to maintain the appearance of an unchanged Ac:Glc utilization ratio. This is consistent with our findings of reduced enrichment of Glu C4 from [1,2-13C2] acetate at day 1 post-FPI (Table 2). There was no difference in the Ac:Glc ratio of Gln or Glu synthesis in the right hemisphere of any of the post-FPI groups (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

The acetate:glucose utilization ratio for the synthesis of glutamate and glutamine in the left/injured (A), and right (B) hemisphere, of sham animals and the day 1, day 5, and day 14 post-FPI groups. There is a significant increase in the acetate:glucose utilization ratio for glutamine at day 1 post-FPI in the left/injured hemisphere compared to both the sham and day 14 post-FPI groups. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (FPI, fluid percussion injury). *p < 0.05 compared to sham-controls.

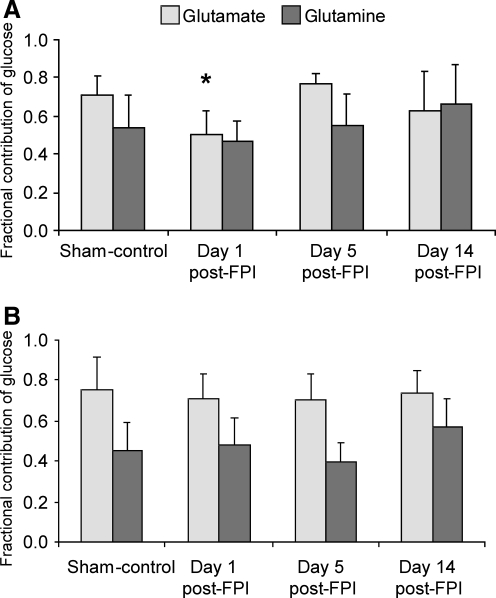

Relative contribution of glucose and acetate to amino acid synthesis

Figure 4 shows the contribution of glucose to the synthesis of Glu and Gln C4 during the first turn of the TCA cycle in the left/injured and right hemispheres of the study groups. Compared to the sham group, there was a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the contribution of glucose to Glu synthesis in neurons of the left/injured hemisphere at day 1 post-FPI (Fig. 4A), but not at days 5 and 14. In contrast, there were no significant group differences in the contribution of glucose to Gln synthesis in astrocytes of the left/injured hemisphere at any day post-FPI (Fig. 4A), or in the synthesis of Glu or Gln in the right hemisphere of the FPI groups (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

The contribution of glucose to the synthesis of glutamate and glutamine in the left/injured (A) and right (B) hemispheres, of sham animals and those in the day 1, day 5, and day 14 post-FPI groups. There was a significant decrease in the contribution of glucose for glutamate synthesis at day 1 post-FPI in the left/injured hemisphere compared to both the sham and day 5 post-FPI groups. In contrast, FPI did not alter the contribution of glucose to the synthesis of glutamine. Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (FPI, fluid percussion injury). *p < 0.05 compared to sham-controls.

We were unable to calculate the contribution of acetate to Gln and Glu synthesis in this study, as Glc C1 and C6 resonances derived from acetate metabolism were not detected in the NMR spectra of our hemispheric brain samples.

Discussion

That there are metabolic consequences following TBI is well established in both humans and in animal models. These include alterations in glucose uptake and utilization (Bergsneider et al., 1997, 2000, 2001; Moore et al., 2000; Yoshino et al., 1991), decreased energy (ATP and phosphocreatine) levels (Buczek et al., 2002; Marklund et al., 2006; Sullivan et al., 1998; Vink et al., 1994), and functional and structural mitochondrial changes (Harris et. al, 2001; Hovda et al., 1991; Lifshitz et al., 2003; Sullivan et al., 2002; Verweij et al., 2000; Xiong et al., 1997). Despite all that is known, it is less clear if these metabolic changes occur equally in both neurons and astrocytes. In a preliminary study using double-labeled 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose and 14C-acetate autoradiography, we showed that CMRglc was reduced in both neurons and astrocytes at 24 and 72 h following FPI, but that the CMRacetate in astrocytes was reduced at 24 h only (Sutton et al., 2005). These observations suggested that metabolic impairments are less severe or recover more quickly in astrocytes. 13C NMR spectroscopy studies using 13C-labeled glucose within the first 24 h after injury showed decreased glucose oxidation in both neurons and astrocytes at 3.5 h post-FPI in adult rats (Bartnik et al., 2007b), and at 5 h after controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury in juvenile rats (Scafidi et al., 2009). The present study was designed to expand our understanding of cell-specific decreases in oxidative metabolism, as [1,2-13C2] acetate is metabolized solely in astrocytes, whereas [1-13C] glucose is metabolized in both cell types, although to a greater extent in neurons (Qu et al., 2000).

Neuronal oxidative metabolism following FPI

The enrichment of Glu isotopomers from [1-13C] glucose in neurons was significantly reduced at day 1 and returned towards sham levels by day 14 post-FPI, indicating that injury-induced decreases in neuronal oxidative metabolism recover over time. Our findings are consistent with the time course of reduced CMRglc following an FPI described by Yoshino and associates (1991), and by Moore and colleagues (2000). Since the synthesis of Glu requires the entry of carbon skeletons into the neuronal TCA cycle, decreased Glu C4 enrichment in the first turn of the TCA cycle suggests that glucose metabolism may be affected at the point of pyruvate decarboxylation to acetyl CoA via PDH. Decreased PDH enzyme activity has been previously reported following CCI injury in both adult and juvenile rats (Bartnik et al., 2007a; Opii et al., 2007; Scafidi et al., 2009; Xing et al., 2009), and following FPI (Sharma et al., 2009). Moreover, other data suggest that decreased PDH enzyme activity following an experimental TBI is the result of increased phosphorylation of the E1α1 subunit (Xing et al., 2009). The enrichment of Glu C2 and Glu C3 occurs when carbon skeletons remain in the neuronal TCA cycle beyond the first turn. Our observation of decreased Glu C2 enrichment at day 1 and decreased Glu C3 enrichment at day 5 post-FPI is consistent with a reduction in the entry of carbon to the neuronal TCA cycle, leading to an inadequate supply of TCA cycle intermediates following TBI.

Astrocyte oxidative metabolism following FPI

The enrichment of Gln C4 from [1-13C] glucose in astrocytes was significantly decreased at day 1 post-FPI, whereas the enrichment of Gln C2 and C3 was similar to sham levels. This finding is consistent with those of Sutton and associates (2005), and suggests that astrocytes retain a greater capacity for oxidative glucose metabolism during the hypometabolic period. In addition, the oxidation of [1,2-13C2] acetate to Gln in astrocytes did not decrease following the FPI, indicating that acetate, which enters the astrocyte TCA cycle as acetyl CoA, ensures adequate acetyl CoA levels to maintain oxidative metabolism in these cells. Our finding is consistent with a recent study in which it was reported that the intragastric administration of the acetate precursor glyceryltriacetate increased levels of both N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) and ATP in brain homogenates of animals following a CCI injury (Arun et al., 2010).

In this study we also observed that the Ac:Glc utilization ratio for Gln synthesis and the enrichment of Gln C4 from [1,2-13C2] acetate were increased at day 1 post-FPI. Since acetate is metabolized exclusively in astrocytes, these observations lend support to a beneficial role for astrocytes in supplying substrates to neurons following TBI. Examples of neuronal metabolic support via astrocytes are numerous, and include observations of Gln being used as an energy substrate for neurons (Peng et al., 2007; Yu et al., 1984), replenishing neuronal TCA cycle intermediates (Shokati et al., 2005), and maintaining normal oxygen consumption during glucose and/or oxygen deprivation (Bambrick et al., 2004; Hertz, 2003; Peng et al., 2007).

Metabolic trafficking

An important goal of this study was to examine the effect of injury on the exchange of metabolites between neurons and astrocytes. The Glu-Gln cycle provides a metabolic link between the two cell types and functions to ensure: (1) the rapid removal of Glu from the synapse, (2) the recycling of Glu, and (3) the provision of a steady supply of Gln that can act as a potential fuel to support ongoing oxidative metabolism in neurons (reviewed in Daikhin and Yudkoff, 2000). In cell culture, approximately 40–50% of all Glu synthesized results from the metabolism of Gln in the neuronal TCA cycle (Waagepetersen et al., 2005). In the present study we used a combination of [1-13C] glucose and [1,2-13C2] acetate to more clearly appreciate the link between neuron and astrocyte metabolism following FPI. Since acetate is metabolized solely in the astrocyte compartment, the labeling of Glu from acetate requires the trafficking of Gln synthesized in astrocytes to neurons, and reflects the functional activity of the Glu-Gln cycle. In the left hemisphere of the sham group, 36.7 ± 8.5% of the total 13C Glu pool measured was the result of the exchange and subsequent metabolism of Gln synthesized in astrocytes from acetate (Table 2). Following FPI, the contribution of the Glu-Gln cycle to Glu synthesis in the left/injured hemisphere was 41.9 ± 7.2% at day 1, 34.4 ± 91% at day 5, and 50.9 ± 3.4% at day 14, indicating that the trafficking and metabolism of astrocyte-synthesized Gln in neurons is functional during this time period after injury. These findings reflect only the synthesis and transport of amino acids from astrocytes to neurons following injury. Given that both neurons and astrocytes metabolize glucose, we were unable to determine if the transport and uptake of neuronal-derived Glu in astrocytes is affected at these time points using this methodology.

Study limitations

The tissue samples used to optimize NMR spectra in the present study limited our ability to detect potential isolated or focal regional alterations in metabolism over time after injury. For example, a decrease in CMRglc was observed throughout the ipsilateral hemisphere at day 1, but was limited to the frontal and temporal cortex by day 5 post-FPI (Yoshino et al., 1991). In using the entire hemisphere for our current analyses, there may have been a “dilution effect” due to inclusion of metabolically normal tissue that affected our findings. If this is the case, our results would represent an underestimation of the extent of the decreases in oxidative metabolism. Regardless, our findings that neurons show a more pronounced reduction in oxidative metabolism compared to astrocytes after FPI still apply.

Owing to the rapid exchange of metabolites and the cycling of intermediates through the TCA cycle, it becomes more difficult with time to differentiate the source of isotopomer labeling from glucose. For example, measurements of PC activity are limited by time, as the percentage of glucose metabolized through PC relative to PDH decreases to approximately 30% after 60 min (Merle et al., 2002). In 13C NMR spectroscopy studies, the contribution of PC to Gln synthesis can be measured from the difference in glucose enrichment between Gln C2 and Gln C3, where C2 in excess of C3 is the result of glucose metabolism via PC. Due to the 60-min infusion used in the current study, the glucose enrichment of Gln C2 was equal to that of Gln C3 in the sham as well as the post-FPI groups. Given that PC catalyzes a significant anaplerotic reaction in the brain, future studies using short infusion times are needed to determine if this important pathway is affected during the hypometabolic period following FPI.

Conclusions

Overall, the results of the present study support previous findings that oxidative metabolism in both neurons and astrocytes is altered following an FPI and extends those earlier observations past the first 24 h through to the resolution of the hypometabolic period at 14 days post-injury. In this study we have provided evidence that astrocytes retain a greater capacity for glucose oxidative metabolism, and that these cells increase their net synthesis of Gln from acetate in a time-dependent manner during the hypometabolic period. Moreover, the trafficking of metabolites between neurons and astrocytes remained functional during the period of the study. We believe that these metabolic adjustments provide an underlying mechanism for the protective role of astrocytes in maintaining and/or restoring oxidative metabolism after FPI, via the trafficking of Gln between the cellular compartments.

These findings could have significant implications in the management of clinical TBI patients, as a similar methodology using 13C-labeled compounds demonstrated the use of acetate and lactate as an energy source in the traumatically-injured human brain (Gallagher et al., 2009). Designing therapies that enhance oxidative metabolism in astrocytes would ensure an adequate supply of TCA cycle intermediates for both neurons and astrocytes, and may possibly lead to significant cell sparing. For example, in pre-clinical studies of pediatric and adult TBI, alternative metabolic fuels such as β-hydroxybutyrate, and sodium or ethyl pyruvate have shown significant neuroprotection following injury (Fukushima et al., 2009; Moro and Sutton, 2010; Prins et al., 2004, 2005). Although complex, their neuroprotective effects may include the ability of these compounds to enter the TCA cycle and serve as substrates for energy production. Specifically, β-hydroxybutyrate has been shown to increase astrocyte metabolism of Gln, Glu, GABA, and aspartate (Melo et al., 2006), whereas sodium or ethyl pyruvate treatment may enhance metabolic coupling between neurons and astrocytes, via metabolism of pyruvate to lactate and activation of the astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle (Tsacopoulos and Magistretti, 1996). The effects of these alternative metabolic fuels on neuronal versus astrocyte metabolism warrant further study, as the present results implicate a key role for astrocytes in metabolic protection/recovery following TBI.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. N.G. Harris for his review and comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center and Award Numbers R01NS27544 and P01NS058489 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINDS or the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Arun A. Ariyannur P.S. Moffett J.R. Xing G. Hamilton K. Grunberg N.E. Ives J.A. Namboodiri A.M. Metabolic acetate therapy for the treatment of traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2010;27:293–298. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badar-Goffer R.S. Bachelard H.S. Morris P.G. Cerebral metabolism of acetate and glucose studied by 13C-n.m.r. spectroscopy. A technique for investigating metabolic compartmentation in the brain. Biochem. J. 1990;266:133–139. doi: 10.1042/bj2660133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambrick L. Kristian T. Fiskum G. Astrocyte mitochondrial mechanisms of ischemic brain injury and neuroprotection. Neurochem. Res. 2004;29:601–608. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000014830.06376.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartnik B.L. Hovda D.A. Lee P.W. Glucose metabolism after traumatic brain injury: estimation of pyruvate carboxylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase flux by mass isotopomer analysis. J. Neurotrauma. 2007a;24:181–194. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartnik B.L. Lee S.M. Hovda D.A. Sutton R.L. The fate of glucose during the period of decreased metabolism after fluid percussion injury: a 13C NMR study. J. Neurotrauma. 2007b;24:1079–1092. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsneider M. Hovda D.A. Lee S.M. Kelly D.F. McArthur D.L. Vespa P.M. Lee J.H. Huang S.C. Martin N.A. Phelps M.E. Becker D.P. Dissociation of cerebral glucose metabolism and level of consciousness during the period of metabolic depression following human traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2000;17:389–401. doi: 10.1089/neu.2000.17.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsneider M. Hovda D.A. McArthur D.L. Etchepare M. Huang S.C. Sehati N. Satz P. Phelps M.E. Becker D.P. Metabolic recovery following human traumatic brain injury based on FDG-PET: time course and relationship to neurological disability. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 2001;16:135–148. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200104000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergsneider M. Hovda D.A. Shalmon E. Kelly D.F. Vespa P.M. Martin N.A. Phelps M.E. McArthur D.L. Caron M.J. Kraus J.F. Becker D.P. Cerebral hyperglycolysis following severe traumatic brain injury in humans: a positron emission tomography study. J. Neurosurg. 1997;86:241–251. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.86.2.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buczek M. Alvarez J. Azhar J. Zhou Y. Lust W.D. Selman W.R. Ratcheson R.A. Delayed changes in regional brain energy metabolism following cerebral concussion in rats. Metab. Brain Dis. 2002;17:153–167. doi: 10.1023/a:1019973921217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz F. Cerdan S. Quantitative 13C NMR studies of metabolic compartmentation in the adult mammalian brain. NMR Biomed. 1999;12:451–462. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1492(199911)12:7<451::aid-nbm571>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daikhin Y. Yudkoff M. Compartmentation of brain glutamate metabolism in neurons and glia. J. Nutrition. 2000;130:1026S–1031S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.4.1026S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima M. Lee S.M. Moro N. Hovda D.A. Sutton R.L. Metabolic and histologic effects of sodium pyruvate treatment in the rat after cortical contusion injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2009;26:1095–1110. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher C.N. Carpenter K.L.H. Grice P. Howe D.J. Mason A. Timofeev I. Menon D.K. Kirkpatrick P.J. Pickard J.D. Sutherland G.R. Hutchinson P.J. The human brain utilizes lactate via the tricarboxylic acid cycle: a 13C-labelled microdialysis and high-resolution nuclear magnetic resonance study. Brain. 2009;132:2839–2849. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraju V. Young K. Maudsley A.A. Proton NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants for brain metabolites. NMR Biomed. 2000;13:129–153. doi: 10.1002/1099-1492(200005)13:3<129::aid-nbm619>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L.K. Black R.T. Golden K.M. Reeves T.M. Povlishock J.T. Phillips L.L. Traumatic brain injury-induced changes in gene expression and functional activity of mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase. J. Neurotrauma. 2001;18:993–1009. doi: 10.1089/08977150152693692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L. Astrocytic amino acid metabolism under control conditions and during oxygen and/or glucose deprivation. Neurochem. Res. 2003;28:243–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1022377100379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovda D.A. Yoshino A. Kawamata T. Katayama Y. Becker D.P. Diffuse prolonged depression of cerebral oxidative metabolism following concussive brain injury in the rat: a cytochrome oxidase histochemistry study. Brain Res. 1991;567:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifshitz J. Friberg H. Neumar R.W. Raghupathi R. Welsh F.A. Janmey P. Saatman L.E. Wieloch T. Grady M.S. McIntosh T.K. Structural and functional damage sustained by mitochondria after traumatic brain injury in the rat: evidence for differentially sensitive populations in the cortex and hippocampus. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:219–251. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000040581.43808.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marklund N. Salci K. Ronquist G. Hillered L. Energy metabolic changes in the early post-injury period following traumatic brain injury in rats. Neurochem. Res. 2006;31:1085–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M.C. The glutamate-glutamine cycle is not stoichiometric: fates of glutamate in brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:3347–3358. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo T.M. Nehlig A. Sonnewald U. Neuronal-glial interactions in rats fed a ketogenic diet. Neurochem. Intl. 2006;48:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merle M. Bouzier-Sore A.K. Canioni P. Time-dependence of the contribution of pyruvate carboxylase versus pyruvate dehydrogenase to rat brain glutamine labeling from [1-(13) C] glucose metabolism. J. Neurochem. 2002;82:47–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A.H. Osteen C.L. Chatziioannou A.F. Hovda D.A. Cherry S.R. Quantitative assessment of longitudinal metabolic changes in vivo after traumatic brain injury in the adult rat using FDG-microPET. J. Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:1492–1501. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro N. Sutton R.L. Beneficial effects of sodium or ethyl pyruvate after traumatic brain injury in the rat. Exp. Neurol. 2010;225:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg M.D. Martinez-Hernandez A. Fine structural localization of glutamine synthetase in astrocytes of rat brain. Brain Res. 1979;161:303–310. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opii W.O. Nukala V.N. Sultana R. Pandya J.D. Day K.M. Merchant M.L. Klein J.B. Sullivan P.G. Butterfield D.A. Proteomic identification of oxidized mitochondrial proteins following experimental traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:772–789. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteen C.L. Giza C.C. Hovda D.A. Injury-induced alterations in N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor subunit composition contribute to prolonged (45)calcium accumulation following lateral fluid percussion. J. Neurotrauma. 2004;128:305–322. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L. Gu L. Zhang H. Huang X. Hertz E. Hertz L. Glutamine as an energy substrate in cultured neurons during glucose deprivation. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:3480–3486. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins M.L. Fujima L.S. Hovda D.A. Age-dependent reduction of cortical contusion volume by ketones after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005;82:413–420. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins M.L. Lee S.M. Cheng C.L.Y. Becker D.P. Hovda D.A. Fluid percussion brain injury in the developing and adult rat: a comparative study of mortality, morphology, intracranial pressure and mean arterial blood pressure. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 1996;95:272–282. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(96)00098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins M.L. Lee S.M. Fujima L. Hovda D.A. Increased cerebral uptake and oxidation of exogenous beta HB improves ATP following traumatic brain injury in adult rats. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:666–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu H. Haberg A. Haraldseth O. Unsgard G. Sonnewald U. (13)C MR spectroscopy study of lactate as substrate for rat brain. Dev. Neurosci. 2000;22:429–436. doi: 10.1159/000017472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scafidi S. O'Brien J. Hopkins I. Robertson C. Fiskum G. McKenna M. Delayed cerebral oxidative glucose metabolism after traumatic brain injury in young rats. J. Neurochem. 2009;109(Suppl. 1):189–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A. Westergaard N. Waagepetersen H.S. Larsson O.M. Bakken I.J. Sonnewald U. Trafficking between glia and neurons of TCA cycle intermediates and related metabolites. Glia. 1997;21:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serres S. Bezancon E. Franconi J.M. Merle M. Brain pyruvate recycling and peripheral metabolism: an NMR analysis ex vivo of acetate and glucose metabolism in the rat. J. Neurochem. 2007;101:1428–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serres S. Raffard G. Franconi J.M. Merle M. Close coupling between astrocytic and neuronal metabolisms to fulfill anaplerotic and energy needs in the rat brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:712–724. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shank R.P. Bennett G.S. Freytag S.O. Campbell G.L. Pyruvate carboxylase: an astrocyte-specific enzyme implicated in the replenishment of amino acid neurotransmitter pools. Brain Res. 1985;329:364–367. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90552-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma P. Benford B. Li Z.Z. Ling G.S. Role of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in traumatic brain injury and measurement of pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme by dipstick test. J. Emerg. Trauma Shock. 2009;2:67–72. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.50739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokati T. Zwingmann C. Leibfritz D. Contribution of extracellular glutamine as an anaplerotic substrate to neuronal metabolism: a re-evaluation by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy in primary cultured neurons. Neurochem. Res. 2005;30:1269–1281. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-8798-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnewald U. Kondziella D. Neuronal glial interaction in different neurological diseases studied by ex vivo 13C NMR spectroscopy. NMR Biomed. 2003;16:424–429. doi: 10.1002/nbm.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P.G. Keller J.N. Bussen W.L. Scheff S.W. Cytochrome c release and caspase activation after traumatic brain injury. Brain Res. 2002;949:88–96. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02968-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P.G. Keller J.N. Mattson M.P. Scheff S.W. Traumatic brain injury alters synaptic homeostasis: implications for impaired mitochondrial and transport function. J. Neurotrauma. 1998;15:789–798. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R.L. Aoyama N. Hovda D.A. Lee S.M. Oxidative metabolism recovers more rapidly in astrocytes than in neurons after experimental traumatic brain injury. Program No. 471.7, 2005 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, Washington D.C. Society for Neuroscience. CD-ROM 2005 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A. McLean M. Morris P. Bachelard H. Approaches to studies on neuronal/glial relationships by 13C-MRS analysis. Dev. Neurosci. 1996;18:434–442. doi: 10.1159/000111438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsacopoulos M. Magistretti P.J. Metabolic coupling between neurons and astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:877–885. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-00877.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg C.J. Garfinkel D. A simulation study of brain compartmentation. Metabolism of glutamate and related substances in mouse brain. Biochem. J. 1971;123:211–218. doi: 10.1042/bj1230211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg C.J. Krzalic L.J. Mela P. Waelsch H. Compartmentation of glutamate metabolism in brain. Evidence for the existence of two different tricarboxylic acid cycles in brain. Biochem. J. 1969;113:281–290. doi: 10.1042/bj1130281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij B.H. Muizelaar J.P. Vinas F.C. Peterson P.L. Xiong Y. Lee C.P. Impaired cerebral mitochondrial function after traumatic brain injury in humans. J. Neurosurg. 2000;93:815–820. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.5.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P. Boonyaputthikul R. McArthur D.L. Miller C. Etchepare M. Bergsneider M. Glenn T. Martin N. Hovda D. Intensive insulin therapy reduces microdialysis glucose values without altering glucose utilization or improving the lactate/pyruvate ratio after traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med. 2006;34:850–856. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000201875.12245.6F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespa P.M. McArthur D. O'Phelan K. Glenn T. Etchepare M. Kelly D. Bergsneider M. Martin N.A. Hovda D.A. Persistently low extracellular glucose correlates with poor outcome 6 months after human traumatic brain injury despite a lack of increased lactate: a microdialysis study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:865–877. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000076701.45782.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink R. Golding E.M. Headrick J.P. Bioenergetic analysis of oxidative metabolism following traumatic brain injury in rats. J. Neurotrauma. 1994;11:265–274. doi: 10.1089/neu.1994.11.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waagepetersen H.S. Qu H. Sonnewald U. Shimamoto K. Schousboe A. Role of glutamine and neuronal glutamate uptake in glutamate homeostasis and synthesis during vesicular release in cultured glutamatergic neurons. Neurochem. Int. 2005;47:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waniewski R.A. Martin D.L. Preferential utilization of acetate by astrocytes is attributable to transport. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:5225–5233. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05225.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing G. Ren M. Watson W.A. O'Neil J.T. Verma A. Traumatic brain injury-induced expression and phosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase: a mechanism of dysregulated glucose metabolism. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;454:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y. Gu Q. Peterson P.L. Muizelaar J.P. Lee C.P. Mitochondrial dysfunction and calcium perturbation induced by traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1997;14:23–34. doi: 10.1089/neu.1997.14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino A. Hovda D.A. Kawamata T. Katayama Y. Becker D.P. Dynamic changes in local cerebral glucose utilization following cerebral concussion in rats: evidence of a hyper- and subsequent hypometabolic state. Brain Res. 1991;561:106–119. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90755-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu A.C. Drejer J. Hertz L. Schousboe A. Pyruvate carboxylase activity in primary cultures of astrocytes and neurons. J. Neurochem. 1983;41:1484–1487. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb00849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu A.C. Hertz E. Hertz L. Alterations in uptake and release rates for GABA, glutamate, and glutamine during biochemical maturation of highly purified cultures of cerebral cortical neurons, a GABAergic preparation. J. Neurochem. 1984;42:951–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb12696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]