Abstract

Objectives

Psychosocial factors such as anxiety or optimism may be related to the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, but the evidence is conflicting.

Methods

We investigated the relation between maternal anxiety, optimism, gestational age and infant birth weight in a cohort of 667 nulliparous women from the Prenatal Exposures and Preeclampsia Prevention study, Pittsburgh PA. Women completed the Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Life Orientation Test at 18 weeks gestation. Linear and logistic regression models assessed the relation of anxiety and optimism to gestational age, birth weight centile, preterm delivery (<37 weeks) or small for gestational age (<10th percentile) births.

Results

After adjustment for age, race, preeclampsia, and smoking, higher anxiety was associated with decreasing gestational age (−1.6 days per SD increase in anxiety score, p=0.06). This relationship was modified by maternal race (p<0.01 for interaction). Among African American women, each SD increase in anxiety was associated with gestations that were, on average, 3.7 days shorter (p=0.03). African American women with anxiety in the highest quartile had gestations that were 8.2 days shorter, and they had increased risk for preterm birth after excluding cases of preeclampsia (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.08, 2.64). There was no association between anxiety and gestational age among White women. There was also no relation between anxiety, optimism and birth weight centile.

Conclusions

Trait anxiety was associated with a reduction in gestational age and increased risk for preterm birth among African American women. Interventions that reduce anxiety among African American pregnant women may improve pregnancy outcomes.

Keywords: Anxiety, pregnancy, premature birth, fetal growth restriction, cigarette smoking

Preterm birth and fetal growth restriction are dominant determinants of neonatal morbidity and mortality, affecting 5 to 25% of births worldwide (1). Rates of preterm birth continue to increase despite decades of research (2). Physiologic mechanisms that may cause early parturition have been studied extensively, but far less is understood about how psychosocial factors may be related to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Although preterm birth and fetal growth restriction are thought to have distinct pathogeneses, risk factors overlap. Maternal smoking (3–5), nulliparity (5, 6), low socioeconomic status (7, 8), and lean maternal body mass index (6, 9) are risk factors for both preterm birth and growth restriction. Additionally, African American women suffer greater rates of preterm birth and growth restriction (5, 10, 11). There is increasing evidence that measures of stress-related emotions such as anxiety may also be related to the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including low birth weight or preterm delivery(12–20). In addition, one small study of high risk pregnant women indicated that maternal dispositional optimism was related to infant birth weight (21).

A recent meta-analysis indicated that there were still significant gaps in the studies relating anxiety symptoms during pregnancy to adverse perinatal outcomes (22). Conflicting results may be due in part to methodological issues such as assessment of anxiety symptoms late in pregnancy and small sample sizes. In addition, few studies evaluated distinct outcomes such as preterm birth and growth restriction. Finally, very few studies of anxiety during pregnancy have simultaneously evaluated dispositional optimism which may be a marker of a woman’s resiliency and therefore her likelihood to adopt health promoting behaviors.

The goal of this study was to investigate the separate and joint effects of prospectively assessed trait anxiety and dispositional optimism on gestational age and infant birth weight centile. We hypothesized that these psychosocial markers are related to the risk of preterm or growth restricted births as measured by small for gestational age (SGA) independent of the effects of race, socioeconomic status and lifestyle factors.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

The Pregnancy Exposures and Preeclampsia Prevention (PEPP) study is a prospective study of women enrolled at < 21 weeks and followed through the post partum visit. A total of 2812 women were recruited from clinics and private practices from 1997 to 2006. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and all participants provided written informed consent. Beginning in 2002, a psychosocial component was added to the structured interview and enrollment was limited to nulliparous women. Of 942 women eligible for the study after 2002, 795 (84.4%) agreed to participate. These analyses include women who delivered at Magee-Womens Hosptial in Pittsburgh PA (n=702) without chronic hypertension (n=7) who completed the psychosocial instruments (n=667, 95.0%).

The enrollment interview occurred, on average, at 17.6 weeks gestation (SD 3.9 weeks). As part of this interview, women were asked to complete the Speilberger Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), a standard self-report 10 item tool to assess relatively stable individual differences in anxiety proneness (23, 24). Women also completed the Life Orientation Test (LOT-R) which is a standard 10 item tool to assess dispositional optimism that has been used extensively in studies of stress and health (21, 25). Mean scores of these instruments were evaluated, and the primary analysis evaluated each construct as a continuous variable (per SD change). Results divided by quartiles were considered to evaluate threshold effect.

Gestational age was assessed upon delivery based on early pregnancy ultrasounds, and preterm births were those <37 completed weeks. Term births were ≥37 weeks gestation. Small for gestational age infants were those below the 10th percentile of weight according to nomograms based on race, gender and gestational age from a reference population of over 10,000 infants delivered at Magee-Womens Hospital in Pittsburgh PA. Birth weight centile and gestational age were also considered as continuous outcomes.

Covariates

Covariates considered were maternal age at delivery, education (less than high school for women older than 19 who did not complete high school, high school, or > high school), smoking during pregnancy (none, ≤10 cigarettes per day, >10 cigarettes per day), marital status, and race/ethnicity. Due to the small number of women who reported their race/ethnicity as other than African American or White (n=15), results are reported for African American women vs. White and other. Receipt of public assistance was reported as yes if anyone in the household received Medicaid, food stamps, cash assistance or public housing at the time of the interview. Measured height and reported pre-pregnancy weight at the intake visit were used to calculate pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2), and women were classified as underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5–24.9), overweight (25–29.9), or obese (≥30).(26) Preeclampsia during the study pregnancy was considered as de novo systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg on at least two occasions, accompanied by proteinuria and elevated uric acid.(27)

Statistical analysis

Mean scores of the anxiety and optimism measures were compared according to maternal characteristics via student t tests or ANOVA. Pearson correlations were used to evaluate the relation between anxiety, optimism, gestational age and birth weight centile. Separate multivariable linear regression models were built to assess the independent association between anxiety, optimism and gestational age or birth weight centile. We also constructed logistic models to evaluate the relation between these psychosocial measures and preterm birth or SGA. We evaluated the measures of anxiety and optimism as continuous variables (per standard deviation (SD) of change) and as the highest quartile of anxiety (Speilberger >20 vs. ≤20) and the lowest quartile of optimism (LOT-R <12 vs.≥12) in linear and logistic models. We fit parsimonious regression models by specifying full models with potential confounding variables (all covariates were considered), and potential confounders were included if they changed the coefficient (linear regression) or the odds ratio (logistic regression) associated with either anxiety or optimism by >10%. A p-value of <0.05 defined statistical significance. Effect measure modification was evaluated using the likelihood ratio test (p<0.10). Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9.2.(28)

RESULTS

Most women in the study were between the ages of 18 and 25, had more than a high school education, and were unmarried. (Table 1) More than half reported receipt of public assistance and approximately 30% were African American. About 10% of births were preterm and 12.0% were SGA. Overall, the mean score on the anxiety inventory was 17.5 (SD 4.9) and the mean of the optimism index was 14.9 (SD 3.7). Measures of anxiety and optimism were highly inversely correlated (r=−0.67, p<0.01); 67% of women with anxiety in the highest quartile reported optimism in the lowest quartile.

Table 1.

Mean levels of optimism and anxiety according to maternal characteristics

| Optimism | Anxiety | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | LOT-R mean [SD] | p* | Lowest quartile of optimism (LOT-R <12) | p | Speilberger mean [SD] | p* | Highest quartile of anxiety (STAI >20) | p | |

| Maternal age | |||||||||

| <18 | 13 (2.0) | 15.8 (2.5) | <0.01 | 2 (15.4) | <0.01 | 16.5 (4.1) | <0.01 | 3 (23.1) | <0.01 |

| 18 to <25 | 408 (61.2) | 14.0 (3.7) | 141 (34.6) | 18.4 (5.2) | 130 (31.9) | ||||

| 25 to <30 | 141 (21.1) | 15.9 (3.4) | 23 (16.3) | 16.3 (4.4) | 21 (14.9) | ||||

| ≥30 | 105 (15.7) | 16.3 (3.2) | 11 (10.5) | 15.9 (3.9) | 9 (8.6) | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| African American | 200 (30.0) | 14.5 (3.4) | 0.20 | 56 (28.0) | 0.47 | 17.7 (5.0) | 0.49 | 58 (29.0) | 0.07 |

| White | 467 (70.0) | 14.9 (3.8) | 121 (25.9) | 17.5 (4.8) | 105 (22.5) | ||||

| Education † | |||||||||

| < High school | 89 (13.4) | 13.1 (2.6) | <0.01 | 35 (39.3) | <0.01 | 19.6 (4.7) | <0.01 | 39 (43.8) | <0.01 |

| High school | 200 (30.0) | 13.8 (3.5) | 68 (34.0) | 18.4 (5.4) | 61 (30.5) | ||||

| > High school | 377 (56.6) | 15.8 (3.7) | 73 (19.4) | 16.6 (4.4) | 62 (16.5) | ||||

| Public assistance | |||||||||

| Yes | 356 (53.5) | 13.7 (3.4) | <0.01 | 129 (36.2) | <0.01 | 18.0 (5.1) | <0.01 | 115 (32.3) | <0.01 |

| No | 310 (46.6) | 16.1 (3.5) | 48 (15.5) | 16.4 (4.3) | 47 (15.2) | ||||

| Smoking † | |||||||||

| None | 501 (75.1) | 15.3 (3.7) | <0.01 | 117 (23.4) | <0.01 | 17.0 (4.8) | <0.01 | 104 (20.8) | <0.01 |

| <10 cigarettes per day | 144 (21.6) | 13.5 (3.3) | 51 (35.4) | 18.9 (4.8) | 50 (34.7) | ||||

| ≥10 cigarettes per day | 22 (3.3) | 12.9 (4.2) | 9 (40.9) | 20.0 (5.8) | 9 (40.9) | ||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Not married | 371 (55.6) | 13.9 (3.4) | <0.01 | 128 (34.5) | <0.01 | 18.0 (5.1) | <0.01 | 118 (31.8) | <0.01 |

| Married or marriage- like | 296 (44.4) | 15.9 (3.7) | 49 (16.6) | 15.8 (4.4) | 45 (15.2) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||||||

| <18.5 | 42 (6.3) | 14.8 (5.0) | 0.15 | 14 (33.3) | 0.49 | 17.1 (6.3) | 0.23 | 9 (21.4) | 0.47 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 340 (51.2) | 14.8 (3.7) | 91 (26.8) | 17.6 (4.9) | 83 (24.4) | ||||

| 25–29.9 | 147 (22.1) | 15.3 (3.7) | 33 (22.5) | 17.0 (4.6) | 31 (21.1) | ||||

| ≥30 | 135 (20.3 | 14.2 (3.1) | 38 (28.2) | 18.2 (4.8) | 39 (28.9) | ||||

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | |||||||||

| Yes | 65 (9.6) | 14.8 (4.3) | 0.94 | 19 (30.2) | 0.49 | 18.1 (5.4) | 0.34 | 16 (25.4) | 0.85 |

| No | 609 (90.4) | 14.8 (3.6) | 158 (26.2) | 17.5 (4.8) | 147 (24.3) | ||||

| Small for gestational age (<10%) | |||||||||

| Yes | 80 (12.0) | 14.6 (3.6) | 0.67 | 21 (26.3) | 0.97 | 17.2 (4.8) | 0.54 | 19 (23.8) | 0.90 |

| No | 592 (88.0) | 14.8 (3.7) | 155 (26.5) | 17.5 (4.9) | 143 (24.4) | ||||

| Preeclampsia | |||||||||

| Yes | 28 (4.2) | 15.9 (3.6) | 0.12 | 6 (21.4) | 0.53 | 15.9 (4.6) | 0.06 | 1 (3.6) | <0.01 |

| No | 645 (95.8) | 14.8 (3.7) | 171 (26.8) | 17.6 (4.9) | 162 (25.4) | ||||

t test or ANOVA

p for trend <0.01

Anxiety was higher and optimism was lower among women not married and those who reported receipt of public assistance (Table 1). Anxiety was higher and optimism was lower among women with fewer years of education (p for trend<0.01) and as smoking levels increased (p for trend <0.01). Women age 18 to <25 had higher levels of anxiety and lower levels of optimism compared to other age groups. In addition, African American women were somewhat more likely to report anxiety scores in the highest quartile compared to White women (29.0% vs. 22.5%, p=0.07). The prevalence of low optimism, however, did not vary by race (p=0.57). There were no significant differences in anxiety or optimism scores among women with preterm or SGA births, although women who developed preeclampsia tended to have lower anxiety scores were less likely to report anxiety in the highest quartile.

As anxiety scores increased, gestational age at birth decreased. (Table 2). After adjustment for age, race, preeclampsia, and smoking (covariates that met our a priori criteria) each SD increase in anxiety score was associated with gestations that were, on average, 1.6 days shorter (p=0.06). Women with anxiety in the highest quartile (STAI >12) has gestations that were 3.3 days shorter compared to women with anxiety scores below this threshold (p=0.03).

Table 2.

Measures of anxiety and optimism related to gestation age (days) and birthweight centile

| Gestational age (days) | Birth weight centile (percent) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (se) | P-value | Beta (se) | P-value | |

| Anxiety | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Anxiety score (per 5 unit increase in STAI)* | −1.2 (0.64) | 0.05 | 0.59 (1.15) | 0.61 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Anxiety score (per 5 unit increase in STAI)* | −1.2 (0.65) | 0.06 | 1.7 (1.16) | 0.15 |

| Preeclampsia | −13.5 (3.06) | <0.01 | −3.4 (5.51) | 0.53 |

| Black | −4.1 (1.47) | <0.01 | 1.36 (2.66) | <0.01 |

| Smoking 1-<10 cigarettes per day | −4.5 (1.53) | <0.01 | −11.1 (2.78) | <0.01 |

| Smoking >10 cigarettes per day | −7.1 (3.43) | 0.04 | −17.2 (6.22) | 0.67 |

| Age | −0.2 (0.13) | 0.08 | 0.1 (0.24) | 0.61 |

| Optimism | ||||

| Unadjusted | ||||

| Optimism score (per 4 unit increase in LOT)* | 0.66 (0.64) | 0.30 | 1.86 (1.19) | 0.12 |

| Adjusted | ||||

| Optimism score (per 4 unit increase in LOT)* | 0.49 (0.66) | 0.46 | 0.86 (1.24) | 0.49 |

| Preeclampsia | −14.00 (3.00) | <0.01 | −5.40 (5.59) | 0.33 |

| Black | −3.22 (1.40) | 0.02 | 1.02 (2.64) | 0.70 |

| Smoking 1-<10 cigarettes per day | −5.09 (1.48) | <0.01 | −10.05 (2.79) | <0.01 |

| Smoking >10 cigarettes per day | −6.44 (3.36) | 0.06 | −16.45 (6.33) | <0.01 |

| Age | −0.18 (0.13) | 0.17 | 0.03 (0.24) | 0.99 |

Anxiety and optimism scores analyzed per 1 standard deviation change

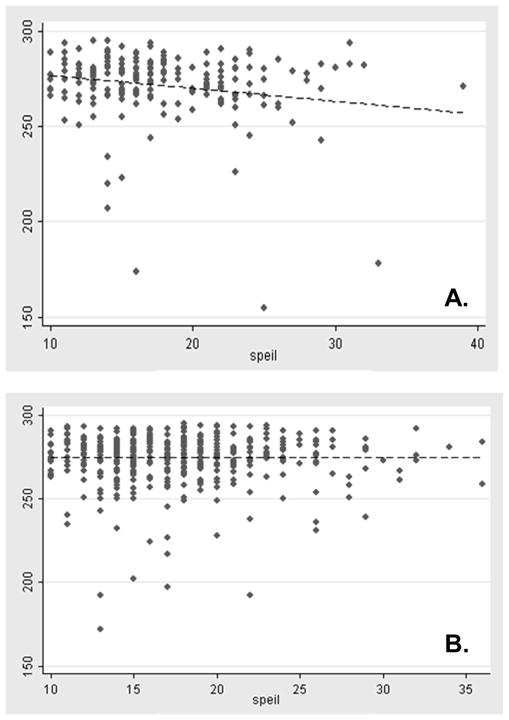

There was strong evidence that the relationship between anxiety and gestational age at birth was modified by maternal race (p<0.01 for interaction). When stratified by maternal race, the association between anxiety and gestational age appeared to be particularly relevant among African American women (Table 3 and Figure 1). For each SD increase in anxiety score, gestational age decreased among African American women by 3.7 days (p<0.01). African American women with high anxiety (STAI >12), had gestations that were 8.2 days shorter compared to women with anxiety below this level (p<0.01). There was no relationship between anxiety scores and gestational age among White women.

Table 3.

Association between gestational age (days) and anxiety among African American and White women

| African American women (n=200) | White women (n=467) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (se) | P-value | Beta (se) | P-value | |

| Anxiety score (per 5 unit increase in STAI)* | −3.7 (1.30) | <0.01 | 0.2 (0.73) | 0.78 |

| Preeclampsia | −15.1 (5.91) | 0.01 | −12.7 (3.49) | <0.01 |

| Smoking 1-<10 cigarettes per day | −4.6 (3.49) | 0.19 | −3.9 (1.65) | 0.02 |

| Smoking >10 cigarettes per day | 4.1 (8.89) | 0.65 | −10.5 (3.54) | <0.01 |

| Age | −0.6 (0.42) | 0.15 | −0.1 (0.13) | 0.36 |

Figure 1.

Association between gestational age (days) and anxiety (STAI), stratified by maternal race [A. African American women, n=200; B. White women, n=467].

There was a modest association between increasing anxiety and the risk of preterm birth among African American women (OR 1.48, 95% CI 0.96, 2.28), adjusted for covariates. After excluding cases of preeclampsia, the magnitude of this association increased (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.08, 2.64).

There was no association between anxiety and preterm birth among White women (OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.74, 1.47), and these results were unchanged after excluding cases of preeclampsia. There was no association between optimism and gestational age in the study population (Table 2), nor was there evidence that this relationship was modified by maternal race (0.23 for interaction). In addition, there was no relation between anxiety or optimism and birth weight centile.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that trait anxiety assessed at 18 weeks gestation was associated with a reduction in gestational age at birth among African American women but not among White women. In addition, non-preeclamptic African American women with higher anxiety appeared to have an increased risk for preterm birth. Neither anxiety nor optimism were associated with birth weight centile in our study.

Anxiety is the most common psychiatric disorder among women (29), and maternal anxiety has been related to both pregnancy outcomes as well as child health and development (30). Most but not all studies report a relation between anxiety or stress and preterm birth (12, 13, 17, 20, 31). Anxiety is an emotional response to stress (32, 33), and because we had no direct measures of stress we were unable to disentangle the cause of the anxiety nor directly evaluate the effects of trait anxiety and current stressors. In addition, some investigators have indicated that pregnancy-related anxiety or stress may be more importantly related to adverse pregnancy outcomes than trait anxiety (34) although to our knowledge these have not been directly compared. A recent meta-analysis indicted that anxiety symptoms during pregnancy were most strongly related to depressive symptoms and social support and thus associated with the same factors as anxiety outside of pregnancy (22). Thus, although stress during pregnancy has a demonstrated association with preterm birth, generalized anxiety may also be important. Our results suggest that this may be particularly relevant for African American women.

In our data, similar to others, low optimism and high anxiety were strongly correlated with measures of socioeconomic disadvantage. Studies of populations with low preterm birth rates and less economic disparities have reported little or no association between maternal anxiety and preterm birth (35, 36). In contrast, studies in the U.S. for the most part have reported a relation between stress or anxiety and preterm birth, especially among African American women (20). Our results are consistent with these findings, and raise the intriguing possibility that African American women may be more likely to report higher trait anxiety compared to white women, while rates of low optimism did not vary by race.

The fact that anxiety in our study was associated with gestational age but not with growth restriction is consistent with other reports (19, 31, 37). Differential effects of anxiety therefore may be related to different etiologies of preterm birth and SGA. For example, chronic anxiety and stress during pregnancy have been related to elevated CRH(38) and proinflammatory cytokines that affect immune responses that are important in preterm birth (14, 15). In contrast, for preeclampsia (which actually had an inverse relationship with anxiety in our study) and growth restriction anxiety may not be as important a pathway, although future studies should explore this possibility.

Our results should be considered preliminary as they are based on a modest size study population which limited the precision of our estimates. Although our assessments of anxiety and optimism were based on validated tools administered prospectively, we were limited to only one antenatal assessment. One study demonstrated that trait anxiety was relatively stable across gestation among medically high risk women (21). As pregnancy progresses, however, women are less physiologically and psychologically reactive to stress (39), and one recent study indicated that the pattern of anxiety and stress during pregnancy is related to preterm birth risk (18). We assessed anxiety and optimism at mid-gestation before clinical indication of complications would affect these dispositional traits and therefore they were assessed with minimal bias. Future studies, however, should assess these characteristics longitudinally. Our study was unique in that we prospectively assessed both anxiety and optimism, and we limited our study to nulliparous women and therefore reduced bias introduced by previous pregnancies (33). We also evaluated many important lifestyle and health behavior traits, and our population was diverse in terms of race and socioeconomic status.

Our results indicate that trait anxiety is associated with socioeconomic disadvantage and high rates of smoking among pregnant women. After accounting for these factors, however, anxiety was independently associated with reductions in gestational age. Gestational age is a more precise marker of fetal maturity than birth weight, and each additional week of gestation, even after 37 completed weeks, is associated with improved newborn survival (40). Thus, on a population level even modest reductions in gestational age impair neonatal health. Intervention research to screen and equip pregnant women, especially African American women, to manage anxiety is an important next step to determine whether reducing anxiety has a direct effect on gestational age and preterm birth risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by NIH-2P01-HD30367 (Preeclampsia Program Project), NIH-5M01-RR00056 (Magee-Womens Clinical Research Center), and the BIRCWH-K12HD043441-06.

References

- 1.Steer P. The epidemiology of preterm labour. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2005;1:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitlin J, Ancel P, Saurel-Cubizolles M, Papiernik E. Are risk factors the same for small for gestational age versus other preterm births. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:208–15. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.114869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox S, Koepsell T, Daling J. Birth weight and smoking during pregnancy-effect modification by maternal age. Am J Epidemiol. 1994;139:1008–15. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiono P, Klebanoff M. Ethnic differences in preterm and very preterm delivery. Am J Public Health. 1986;76:1317–21. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.11.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unis K, Beydoun H, Tamim H, Nassif Y, Khogali M. Risk factors for term or near-term fetal growth restriction in the absence of maternal complications. American Journal of Perinatology. 2004;21:227–234. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spencer N. Social, Economic, and Political Determinants of Child Health. 2003. pp. 704–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savitz DA, Kaufman J, Dole N, Siega-Riz AM, Thorp J, Kaczor D. Poverty, education, race, and pregnancy outcome. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:322–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simhan HN, Bodnar LM. Prepregnancy Body Mass Index, Vaginal Inflammation, and the Racial Disparity in Preterm Birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:459–466. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David R, Collins J. Differing birth weight among infants of U.S.-born Blacks, African-born Blacks and U.S.-born Whites. NEJM. 1997;337:1209–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams B, Newman V. Small-for-gestational age birth: maternal predictors and comparison with risk factors of spontaneous delivery in the same cohort. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:785–90. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90516-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borders A, Grobman W, Amsden L, Holl J. Chronic stress and low birth weight neonates in a low-income population of women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:331–8. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000250535.97920.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A, Elder N, Swain M, Norman G, Ramsey R, Cotroneo P, Collins BA, Johnson F, Jones P, Meier A. The preterm prediction study: Maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks' gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175:1286–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cousson-Read M, Okun M, Nettles C. Psychosocial stress increases inflammatory markers and alters cytokine production across pregnancy. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2006;21:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coussons-Read MEP, Okun MLMA, Schmitt MPBS, Giese SBS. Prenatal Stress Alters Cytokine Levels in a Manner That May Endanger Human Pregnancy. SO - Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67:625–631. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000170331.74960.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dayan J, Creveuil C, Herlicoviez M, Herbel C, Baranger E, Savoye C, Thouin A. Role of Anxiety and Depression in the Onset of Spontaneous Preterm Labor. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:293–301. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, Buekens P. Maternal Stress and Preterm Birth. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:14–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glynn L, Schetter C, Hobel C, Sandman C. Pattern of perceived stress and anxiety in pregnancy prediccts preterm birth. Health Psychology. 2008;27:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nordentoft M, Lou HC, Hansen D, Nim J, Pryds O, Rubin P, Hemmingsen R. Intrauterine growth retardation and premature delivery: the influence of maternal smoking and psychosocial factors. 1996. pp. 347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orr S, PReiter J, Blazer D, James S. Maternal prenatal pregnancy-related anxiety and spontaneous preterm birth in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:566–570. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180cac25d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lobel M, DeVincent CJ, Kaminer A, Meyer BA. The Impact of Prenatal Maternal Stress and Optimistic Disposition on Birth Outcomes in Medically High-Risk Women. Health Psychology. 2000;19:544–553. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.6.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Littleton HL, Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB. Correlates of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy and association with perinatal outcomes: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;196:424–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lobel M, Dunkel-Schetter C. Conceptualizing stress to study effects on health. Anxiety Research. 1990;3:213–230. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Speilberger C. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rini C, Dunkel-Schetter C, Wadhwa P, Sandman P. Psychological adaptation and birth outcomes: the role of personal resources, stress, and sociocultural context in pregnancy. Psychology. 1999;18:333–345. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Consultation on Obesity. WHO Technical Report Series 894. 2000. Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts JM, Bodnar LM, Lain KY, Hubel CA, Markovic N, Ness RB, Powers RW. Uric Acid Is as Important as Proteinuria in Identifying Fetal Risk in Women With Gestational Hypertension. 2005:1263–1269. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188703.27002.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS. 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2002–2003. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler R, McGonagle K, Ahao S, Nelson C, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen H, Kendler K. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holllins K. Consequences of antenatal mental health problems for child health and development. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:568–572. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3282f1bf28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neggers Y, Goldenberg R, Cliver S, Hauth J. The relationship between psychosocial profile, health practices, and pregnancy outcomes. Informa Healthcare. 2006:277–285. doi: 10.1080/00016340600566121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beydoun H, Saftlas A. Physical and mental health outcomes of prenatal maternal stress in human and animal studies: a review of recent evidence. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22:438–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paarlberg KM, Vingerhoets AJJM, Passchier J, Dekker GA, Van Geijn HP. Psychosocial factors and pregnancy outcome: A review with emphasis on methodological issues. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1995;39:563–595. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lobel M, Cannella D, Graham J, DeVincent C, Schneider J, Meyer B. Pregnancy-specific stress, prenatal health behaviors, and birth outcomes. Health Psychology. 2008;27:604–15. doi: 10.1037/a0013242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andersson L, Sundstrom-Poromaa I, Wulff M, Astrom M, Bixo M. Neonatal Outcome following Maternal Antenatal Depression and Anxiety: A Population-based Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:872–881. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dayan JMDP, Creveuil CP, Marks MNP, Conroy SM, Herlicoviez MMDP, Dreyfus MMDP, Tordjman SMDP. Prenatal Depression, Prenatal Anxiety, and Spontaneous Preterm Birth: A Prospective Cohort Study Among Women With Early and Regular Care. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:938–946. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000244025.20549.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Sabroe S, Secher NJ. The relationship between psychological distress during pregnancy and birth weight for gestational age. Informa Healthcare. 1996:32 –39. doi: 10.3109/00016349609033280. oslash, rgen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mancuso RA, Schetter CD, Rini CM, Roesch SC, Hobel CJ. Maternal Prenatal Anxiety and Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Associated With Timing of Delivery. 2004:762–769. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138284.70670.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthews K, Rodin J. Pregnancy alters bood pressure responses to psychological and physical challenge. Psychophysiology. 1992;29:232–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1992.tb01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander G, Kogan M, Bader D, Carlo W, Allen M, Mor J. US Birth weight/gestational ag-specific neonatal mortality: 1995–1997 rates for Whites, Hispanics, and Blacks. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e61–e66. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]