Abstract

Host-tumor cell interactions are recognized to be critical in tumor development. We have shown that group VIA phospholipase A2 [calcium-independent phospholipase A2β (iPLA2β)] is important in regulating extracellular lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) levels around human epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) cells. To explore the role of iPLA2β in host-tumor cell interactions, we have used immunocompetent iPLA2β knockout (iPLA2β−/−) mice and the mouse EOC cell line ID8. Tumorigenesis and ascites formation were reduced in iPLA2β−/− mice compared with wild-type (WT) mice by more >50% and were reduced further when ID8 cell iPLA2β levels were lowered (by>95%) with shRNA. LPA and lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) levels in the tumor microenvironment were reduced to ∼80% of WT levels in iPLA2β−/− mice. LPA, but not LPC, stimulated ID8 cell migration and invasion with cells in which iPLA2β expression had been down-regulated in vitro. LPA, but not LPC, also enhanced in vivo ascites formation (by ∼5-fold) and tumorigenesis in iPLA2β−/− mice. This is the first demonstration of a role for host cell iPLA2β in cancer, and these findings suggest that iPLA2β is a potential target for developing novel antineoplastic therapeutic strategies.—Li, H., Zhao, Z., Wei, G., Yan, L., Wang, D., Zhang, H., Sandusky, G. E., Turk, J., Xu, Y. Group VIA phospholipase A2 in both host and tumor cells is involved in ovarian cancer development.

Keywords: calcium-independent phospholipase A2β, iPLA2β−/− mice, lysophosphatidic acid, tumor microenvironment

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a bioactive lipid with multiple functions. Ample evidence from epidemiological investigations, experimental animal studies, and cell culture indicates that LPA plays an important role in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) development (1–3). More recently, systematic overexpression or down-regulation of LPA receptors 1–3 in several human EOC cell lines clearly demonstrated that LPA receptors are involved in EOC development (4).

LPA actions can be suppressed by inhibiting its production, by preventing productive receptor occupancy, or by interfering with distal signaling pathways. LPA can be produced by the action of lysophospholipase D (lyso-PLD), e.g., autotaxin (ATX), or via phospholipase A1 or A2 (PLA1 and PLA2; ref. 5). At least 20 distinct PLA2s are recognized and are grouped into various categories based on their cellular localization, substrate specificity, and Ca2+ dependence (6–8). The group VI PLA2 members are intracellular enzymes that do not require Ca2+ for catalytic activity and have been designated iPLA2s. The first recognized group VIA PLA2 was iPLA2β, and there is evidence showing it participates in phospholipid remodeling, signal transduction, cell proliferation, and apoptosis (9). Activation of iPLA2β in nonapoptotic EOC cells via a laminin-β1-integrin-caspase 3 pathway results in LPA generation and arachidonic acid (AA) release from EOC cells (10). LPA and AA are important lipid mediators in chemotaxis and chemokinesis, respectively. Inhibition of iPLA2β activity and/or expression has recently been demonstrated to suppress human EOC cell proliferation and tumorigenesis (11), suggesting that iPLA2β represents a potential target for treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer, which is among the most lethal and difficult to treat human malignancies.

The importance of microenvironment and cell-stroma interactions in tumor pathobiology have received increasing attention in recent years (12). A better understanding of the interplay between tumor and host cells will facilitate the development of more effective therapeutic regimens. Since iPLA2β is expressed in most mouse tissues (13–15) and all cell types tested, it is important to study the role of iPLA2β in host cells to determine whether it might be effectively targeted in the treatment of EOC. For EOC, the mesothelium covering the viscera, extracellular matrix, and peritoneal fluid (ascites) with its associated extravascular blood components compose the microenvironment with which EOC cells interact. Human EOC and peritoneal mesothelial cells have been shown to produce bioactive lipids and cytokines that promote cell migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis (16–20), but these studies were conducted in vitro with isolated cells.

It is essential to study the pathophysiological functions of genes and their products in vivo to develop effective tumor treatment strategies, and gene deletions in knockout mouse lines are particularly useful in that regard. We have generated iPLA2β knockout (iPLA2β−/−) mice, which exhibit reduced male fertility and sperm function, defective signaling in macrophages (13, 21), and several phenotypic abnormalities (9, 13, 14), but the potential role of host cell iPLA2β in tumor biology has not yet been studied. All previously published studies of the role of iPLA2β in EOC were conducted with human EOC cells. To address the role of host cell iPLA2β specifically in EOC using immunocompetent iPLA2β−/− mice on a C57BL/6 genetic background, syngenic mouse cells need to be used. The mouse ID8 EOC cell line was developed with C57BL/6 mice. These cells respond to LPA in a manner similar to that of human EOC cells (22), suggesting that ID8 EOC cells mimic human EOC cell behavior and represent an appropriate model to study tumor pathobiology.

Here, we examined the role of iPLA2β in proliferation, migration, and invasion, using mouse ID8 EOC cells in vitro. The role of iPLA2β in both host and tumor cells in tumorigenesis/metastasis was determined using an experimental metastatic model with ID8 cells injected intraperitoneally. We compared the tumor development and lipid changes in wild-type (WT) and iPLA2β-null mice. The potential functional involvement of LPA and LPC was also examined.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Anti-iPLA2 polyclonal antibody was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA); human laminin and vitronectin from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA, USA); 18:1 LPA and LPC from Avanti Polar Lipids (Birmingham, AL, USA); and the iPLA2 inhibitor bromoenol lactone (BEL) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Four shRNAs against mouse iPLA2 (Mus musculus Pla2g6) were from (cat. no. TR515018; Origene Rockville, MD, USA). The control RNAi was the pRS shRNA cloning plasmid (TR30003). Other reagents were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

The sequences of 4 shRNAs against mouse iPLA2 were as follows: 5′-CCTCAGTAGCGTCACCAACTTGTTCTCGA-3′; 5′-AAGGCGAGACTGCCTTCCATTACGCTGTG-3′; 5′-CGAGAAGCGGAGTCACGACCACCTGCTCT-3′; and 5′- ATCTATGAGCACCGAGAGGAGTTCCAGAA-3′.

Cell culture and transfection

IB8 cells were from Dr. Paul F. Terranova (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, USA) and were transfected with control shRNA or one to more iPLA2 shRNAs using Nucleofector, as described previously (22). Transfected cells were cultured (2 wk) in medium with puromycin (2 μg/ml), and the established stable cell lines are designated ID8-V1 (a vector control line) and ID8-B6 (an iPLA2β-down-regulated line established by using the first and the second shRNAs listed above), respectively.

Migration and invasion assays

These procedures were conducted as described previously (22). Cell migrations were performed in 24-well modified Boyden chambers (Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY, USA) with 8-μm pore size. Briefly, the lower phase of the top chamber was coated with laminin (10 μl) or other extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. ID8 cells were starved overnight, and 5.0 × 104 cells in DMEM (300 μl) were added to the upper chamber. Serum-free DMEM (300 μl) with or without indicated concentrations of LPA or LPC was added to the lower chambers. The chambers were then incubated at 37°C for 4 h. After incubation, the top chambers were rinsed with PBS and swabbed with a cotton swab. The migrated cells were then fixed in methanol for 30 min and stained with crystal violet (Fisher Scientific, Rochester, NY, USA) for 30 min. After the chambers were dried, pictures were taken with a Nikon SMZ 1000 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), and migrated cells were counted in 3 different fields. Invasion assays were performed using modified Boyden's chamber (Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, MA, USA). The Matrigel in the chamber was allowed to swell for 2 h in PBS before the experiment. Cells were starved for 24 h, and then 5.0 × 104 cells were resuspended in DMEM (300 μl). The cells were added to the upper chamber, and serum-free medium (300 μl) with or without LPA was introduced to the lower chamber. The invasion assays were conducted for 16 h. The same method for fixing and counting cells described above for cell migration was used.

RT-PCR and Western blot analyses

The expression levels of iPLA2β were evaluated by RT-PCR or Western blot analyses. PCR primer sequences for mouse iPLA2β were as follows: 5′-AGAAGG GGTGTGCTGAAATG-3′ and 5′-AGATCCTGAAGCTGCTTGCT-3′. Western blot analyses were performed as described previously (22). The expression of LPA receptors in ID8 cells or omentum tissues derived from different mice intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells (ID8-V1 or OD8-B6) was evaluated by RT-PCR. Cells cultured in 6-well plates were harvested and frozen at −80°C. Omentum was excised from mice intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells, along with different treatment, and kept at −80°C. After cells and omentum were homoginized, total RNA was extracted using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) and reverse transcribed by Moloney murine leukemia virus (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Derived cDNAs were amplified using PCR master mix (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Primers were as follows: LPA1, 5′-CTCCGGGATTGGTCTTGTTA-3′ and 5′-ACAGAGTGGTCGTTGCTGTG-3′; LPA2, 5′-TGCTACCTGCACACTTCTGG-3′ and 5′-ACCACTGCATTGACCAGTGA-3′; and LPA3, 5′-AACCTCCTGGCCTTCTTCAT-3′ and 5′-AGCCGTTTTTATTGCACACC-3′.

Animal experiments

iPLA2β-deficient mice were generated as described previously (23) and housed at the Laboratory Animal Resource Center at the Indiana University School of Medicine. Six- to 8-wk-old female mice were used. All surgery was performed under approved animal protocols and conducted as described previously (24, 25).

LPA and LPC were delivered with Alzet microosmotic pumps (model 1002; Alzet, Cupertino, CA, USA). Briefly, the pumps were first siliconized with Sigmacote (Sigma) to prevent lipid from adhering to the wall of the pumps. Pumps containing 100 μl of concentrated LPA (4 mM in PBS), LPC (4 mM in PBS), or PBS were implanted into the peritoneal cavities. The rate of delivery by a pump is controlled by the water permeability of the pump's outer membrane; thus the delivery profile of the pump is independent of the drug formulation dispensed. The pumps continuously release lipids for 14 d at a rate of 0.25 μl/h. An alternative method to deliver LPA or LPC was daily injection of LPA (100 μM in 200 μl of PBS) or LPC (100 μM in 200 μl of PBS) for 4 wk. Following the surgery, ID8-Luc cells (5×106) in 200 μl of PBS were injected into the peritoneal space. Pumps were replaced after 14 d. Animal health was monitored daily. Animals were euthanized when they developed large volumes of ascites (evidenced by abdominal detention). Tumorigenesis was recorded by counting the numbers and sizes of tumor foci on each organ. The ascites or peritoneal wash fluids (2 ml PBS wash) were saved for lipid analyses.

Tissue preparation

Tissues were fixed overnight in neutral buffered formalin (10%) and then transferred to ethanol (70%) before processing through paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were microtomed, and the sections were placed on positive-charged slides. The slides were then baked overnight at 60°C in an oven. Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining was done on the slides.

Immunostaining and quantification

The slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through graded alcohols to water. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling tissue sections in citrate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0) for 10 min followed by cooling at room temperature for 20 min, washing in water, and then proceeding with immunostaining. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with hydrogen peroxide (3%) for 10 min. Tris-buffered saline plus Tween 20 (0.05%, pH 7.4) was used for all washes and diluents. Thorough washing was performed after each incubation. Slides were blocked with universal blocking serum (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 60 min; after being washed, the primary antibody (1 μg/ml of CD31; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was added to the slides and incubated at 4°C for overnight. A biotinylated link antibody plus streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase kit (Vector) was then utilized along with a 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromagen and peroxide substrate to detect the bound antibody complexes. The slides were briefly counterstained with hematoxylin, removed from the autostainer, and dehydrated through graded alcohols to xylene. The slides were coverslipped with a permanent mounting media. For CD31 vascular channel counts, the small capillaries and small vessels were counted per ×20 field. Three fields were counted and averaged. Only small and medium sized capillaries in the field or small vessel diameter capillaries were counted. Large arterioles and veins were not counted.

Lipid analyses

Ascites were collected from peritoneal cavity and left on ice before centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant (cell and cell-debris-free) was collected and stored in siliconized tubes (PGC Scientifics, Frederick, MD, USA) at −80°C for mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. Cell-free peritoneal washings were collected from mice without ascites using 2 ml of PBS, followed by centrifugation (10,000 rpm for 20 min). All lipid extractions were performed either in siliconized tubes or in glass tubes. We (26) have recently developed a simple lipid extraction method. In brief, ascites (10 μl) were added into MeOH (1 ml) with 12:0 LPC (500 pmol) and 14:0 LPA (100 pmol) as the internal standards. After vortex and incubation on ice for 10 min, the mixture was centrifuged (10,000 g for 5 min at room temperature), and the supernatant (120 μl) was directly used for MS analysis. MS analyses were performed using API-4000 (Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX, Forster City, CA, USA) with the Analyst Data Acquisition System. The multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) mode was used for measurement of lipids. Standard curves were established for quantitative analyses of all lipids. Typical operating parameters are as follows: nebulizing gas 15, curtain gas 8, collision-activated dissociation gas 35, electrospray voltage 5000 with positive ion MRM mode or −4200 with negative ion MRM mode, and a heater with temperature at 500°C. The negative ion MRM mode was used for the quantitative analysis of fatty acids, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), and LPAs. HPLC conditions were as same as described previously (26). Samples (10 μl) were loaded through an LC system (Agilent 1100; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) with an auto sampler. The mobile phase was MeOH/water/NH4OH (90:10:0.1, v/v/v), and the HPLC separations were 15 min/sample. The quantitative analyses of LPCs, sphingomyelins, and PCs were determined by the positive ion MRM mode. Since HPLC separation was not necessary for these lipids (27), samples (10 μl) were directly injected into the MS ion source with the mobile phase as MeOH/water/NH4OH (90:10:0.1, v/v/v), and the flow rate was 0.2 ml/min with a duration time at 1.5 min/sample.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as means ± se of ≥3 experiments unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was assessed by Kaplan-Meier for animal average survival studies and by Student's t test for other experiments, with values of P < 0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

Mouse ID8 EOC cells express iPLA2β, which is involved in cell migration and invasion

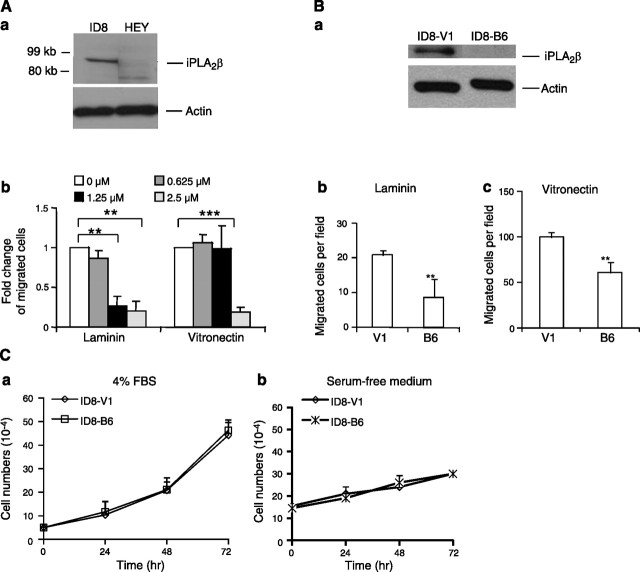

A series of experiments were conducted to determine whether iPLA2β plays roles in mouse ID8 cells similar to those in human cells (10, 11, 16, 28). First, we showed that ID8 cells expressed iPLA2β at levels higher than those of HEY (human EOC) cells (Fig. 1A). A large number of HEY cells are required to detect iPLA2β expression (10). The potential involvement of iPLA2β in cell migration and invasion was examined, since those are tumor cell properties important for metastasis. Several ECM proteins were tested, including laminin (LN), collagen I, fibronectin (FN), and vitronectin (VN), and ID8 cells exhibited the highest haptotactic activity toward VN (22). We found that the haptotactic activity of ID8 cells to VN or LN could be inhibited by the iPLA2β pharmacologic inhibitor BEL (Fig. 1A). Because BEL has been reported to inhibit enzymes in addition to iPLA2β, including phosphatidate phosphohydrolase (29, 30), we also examined effects of down-regulation of iPLA2β expression with shRNA using ID8-B6 cells, which are a stably transfected cell line with reduced iPLA2β expression at the level of RNA (data not shown) and protein (Fig. 1B). This ID8-B6 cell line exhibited reduced haptotatic migratory responses to VN and LN compared with ID8-V1 cells, which are a vector-transfected control cell line (Fig. 1B). Together these observations support a role for iPLA2β in cell migration. In contrast, down-regulation of iPLA2β in ID8 cells did not significantly affect cell proliferation in the presence or absence of serum (Fig. 1C). The doubling time of these cells was ∼24 h in the presence of 4% serum, which was greatly increased in the absence of serum (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

iPLA2β was involved in the haptotatic activity but not in proliferation of ID8 cells. A) a) iPLA2β expression in ID8 and HEY cells. Cells (106) in 6-well plates were lysed, and iPLA2β-immunoreactive protein was determined by Western blot analyses. Cayman iPLA2β antibody recognizes both human and mouse iPLA2β. b) Serum-starved cells were pretreated with BEL (30 min), a specific inhibitor of iPLA2β, which dose dependently inhibited the haptotactic migration of ID8 cells toward laminin and vitronectin. B) a) Western blot indicated iPLA2β expression was down-regulated in ID8-B6 cells vs. ID8-V1 (control cells). b, c) Reduced cell migration to LN (b) and VN (c) was found in ID8-B6 vs. ID8-V1 cells. An ECM protein (10 μl at 10 μg/ml) was used to coat the lower phase of each upper chamber. In migration assay, serum starved cells were added into the upper chamber and serum-free medium was added into the lower chamber. C) iPLA2β was not involved in ID8 cell proliferation. ID8-V1 and ID8-B6 cells were starved overnight and then cultured in 96-well plates with medium containing 4% FBS (a) or serum-free (b) for 24, 48, or 72 h. Cells were trypsinized and counted in the presence of Trypan blue using a hemocytometer. ID8-V1, vector transfected cells; ID8-B6, iPLA2β-knockdown cells. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results represent ≥3 independent experiments.

LPA, but not LPC, stimulates migration and invasion of iPLA2β-down-regulated ID8-B6 cells

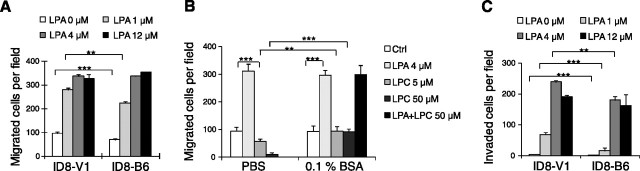

We have reported that iPLA2β overexpression in human EOC cells affects extracellular LPA levels and results in increased cell migration (10). Under similar conditions, we did not observe iPLA2β-dependent changes in extracellular LPA levels with ID8 cells cultured in vitro (data not shown), but ID8 cells did exhibit strong migration and invasion responses to LPA (Fig. 2A, C), as reported for human EOC cells (22). At LPA concentrations below 1 μM, ID8-B6 cells showed reduced migration compared with control cells, but their migration increased in the presence of 4–12 μM LPA, suggesting that iPLA2β is involved in the effects of LPA (may be via an altered LPA responsiveness in these cells) and that higher LPA concentrations can overcome the decreased migratory activity of ID8-B6 cells (Fig. 2A). Similar results were obtained in studies of cell invasion (Fig. 2C). In vivo, LPA and LPC are bound to proteins, such as albumin. LPA stimulated cell migration regardless whether BSA was present or not (Fig. 2B). In contrast, 16:0 LPC (0.1 to 50 μM in the presence of 0.1% BSA) did not affect cell migration itself and also did not affect cell migration stimulated by LPA (Fig. 2B and data not shown). This is consistent with one of our earlier reports and work from others (31).

Figure 2.

iPLA2β is involved in migration and invasion of ID8 cells. A) Higher concentrations of exogenous LPA stimulated the migratory activity in ID8-B6 cells. VN (10 μg/ml) was used to coat migration wells. Cells were added into the upper chamber, and serum-free medium with various dose of LPA was added into the lower chamber. B) LPC did not affect ID8 cell migration when BSA was present. VN was used to coat migration wells. Starved cells were in the upper chamber, and different stimuli were in the lower chamber. C) LPA stimulated cell invasion in ID8-B6 cells. Starved cells were added into the upper chamber, and serum-free medium with LPA was added into the lower chamber. Detailed migration and invasion assays were conducted as described in Materials and Methods. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001. Results represent ≥3 independent experiments.

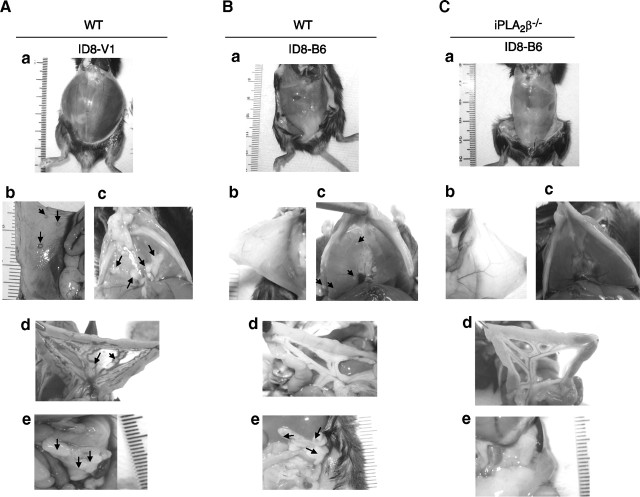

Both host and tumor cell iPLA2β expression are involved in tumorigenesis/metastasis

To determine whether host cell iPLA2β participates in ID8 cell tumorigenesis/metastasis, we used an experimental metastatic model for ovarian cancer in which ID8 cells were injected into the intraperitoneal space of mice. This has been considered a good model of late stages of EOC (32). Tables 1 and Fig. 3 illustrate that tumorigenesis/metastasis in this model was significantly reduced in iPLA2β−/− compared with WT mice, as measured by percentage of peritoneal area covered with tumor nodules, by ascetic fluid volume, and by incidence of tumor nodules. Moreover, survival time was increased in iPLA2β−/− compared with WT mice in this model (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of tumorigenesis/metastasis and ascites formation in WT and iPLA2β−/− mice intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells

| Variable | Mice and treatment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT |

iPLA2β−/− |

|||

| PBS | PBS | LPA | LPC | |

| Mice (n) | 16 | 25 | 8 | 8 |

| Ascites volume (ml) | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 2.2 ± 0.6* | 11 ± 5.6### | 2.0 ± 1.8 |

| % Tumor nodule covering area | 30–50 | <20; 8/25 mice (32%) had no tumors* | 70–95## | <20 |

| Tumor nodule diameter (mm) | <0.5 | <0.5 | >1; detected in 30% mice## | <0.5 |

| Organs affected | PW, D, M, O | PW, D, M | PW, D, M, O | PW, D, M |

| Survival (d) | 83 ± 8 | 90 ± 10 | 70 ± 5### | 93 ± 6 |

Values are means ± se. Female WT or iPLA2β−/− mice were intraperiotenally injected with ID8 cells, and pumps with PBS, LPA, or LPC were placed into the peritoneal cavity. Mice were sacrificed in 10–12 wk, and tumor growth was recorded. Pumps were replaced with new pumps after 14 d; total of 2 pumps/mouse. For tumor development analyses, see Materials and Methods. PW, peritoneal wall; D, diaphragm; M, mesentery; O, omentum.

P <0.05 vs. WT-PBS;

P < 0.01, ##P < 0.01 vs. iPLA2β−/−-PBS; no statistical differences detected for iPLA2β−/−-LPC vs. -PBS.

Figure 3.

Delayed tumor growth and ascites formation in iPLA2β−/− mice and LPA stimulate tumorigenesis and metastasis. ID8 cells (2.5×106) were injected intraperitoneally into mice, which were sacrificed 10 to 12 wk postinjection. WT mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells and treated with PBS; iPLA2β−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells and treated with PBS, LPA, or LPC, respectively. A) Gross observation of ascites formation in peritoneal cavity. B) Tumor growth on the peritoneal wall. C) Tumor metastasis to the diaphragm. D) Tumor development on the mesentery. E) Tumor invasion of omentum. Bold T represents tumor area. Arrows indicate large peritoneal tumors.

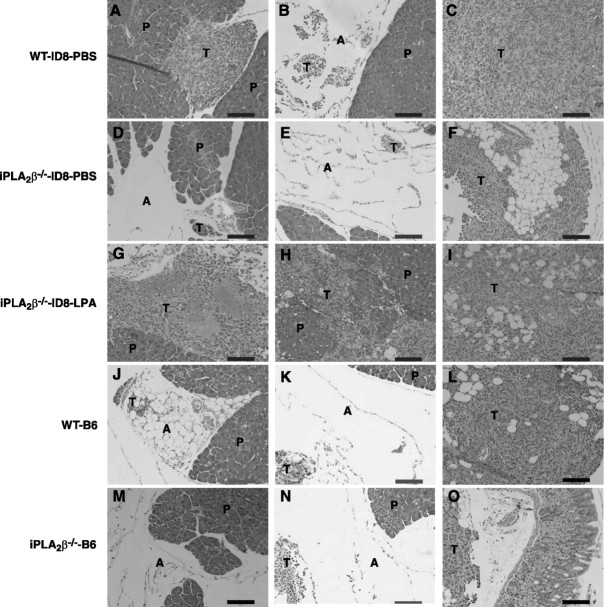

To determine whether tumor cell iPLA2β might also participate in tumorigenesis/metastasis, we compared tumor nodule formation and ascites volume in this model on injection of the ID8-V1 and ID8–B6 cell lines into WT and iPLA2β−/− mice. Table 2 and Fig. 4 illustrate that these parameters were lower in WT mice injected with ID8-B6 cells (which have reduced iPLA2β expression) than those observed after injection of ID8-V1 cells (which express higher levels of iPLA2β). Moreover, ID8-B6 cell metastases were limited to the peritoneal wall and diaphragm, but control ID8-V1 cell metastases were more widely distributed and also involved mesentery and omentum (Table 2 and Fig. 4). ID8-B6 cells injected into iPLA2β−/− mice produced minimal disease with no ascites formation, and only microscopic tumor foci could be detected on H&E staining of the sections (Table 2 and Figs. 3 and 5). This suggests that iPLA2β plays roles in both host and tumor cells that affect the location and numbers of tumor foci and ascites formation. Furthermore, H&E staining of omentum tumor/tissue sections revealed that: 1) ID8 tumors in WT mice developed adjacent to pancreas and adipose and also invaded these tissues (Fig. 5A–C); 2) ID8 tumors in iPLA2β−/− mice were confined to the areas around adipose tissue (Fig. 5D, E); 3) exogenous LPA enhanced formation of tumors adjacent to and invading the pancreas (Fig. 5G–I); and 4) ID8-B6 tumors were small and were confined to adipose tissue in WT and iPLA2β−/− mice (Fig. 5J–O). These data indicate that iPLA2β in both host and tumor cells participates in tumorigenesis/metastasis, which is also promoted by LPA in this in vivo model.

Table 2.

Summary of tumorigenesis/metastasis and ascites formation of ID8-V1 and ID8-B6 cells

| Variable | Mice and tumor cells |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT |

iPLA2β−/− |

|||

| ID8-V1 | ID8-B6 | ID8-V1 | ID8-B6 | |

| Mice (n) | 8 | 10 | 8 | 9 |

| Ascites volume (ml) | 5.6 ± 3.4 | 0*** | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 0*** |

| % Tumor nodule covering area | 30–50 | 0–5*** | <20 | 0–1*** |

| Organs affected | PW, D, M, O | D, O*** | PW, D, M, O | O*** |

Values are means ± se. Female WT and iPLA2β−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8-V1 and ID8-B6, respectively. Mice were sacrificed in 10–12 wk. See experimental details in Materials and Methods.

P < 0.001 vs. corresponding IDV-8.

Figure 4.

Suppression of tumor growth and ascites formation in iPLA2β−/− mice injected with an ID8 cell line in which iPLA2β expression was reduced. WT (A, B) and iPLA2β−/− (C) mice were injected intraperitoneally with vector-transfected cells (ID8-V1; A) or iPLA2β-knockdown cells (ID8-B6; B, C) and sacrificed in 10–12 wk. a) Gross appearance of mice. b) Tumor growth on peritoneal wall. c) Tumor on diaphragm. d) Tumor on mesentery. e) Tumor on omentum. Arrows indicate large peritoneal tumors.

Figure 5.

Histology staining of tumors in mouse omentum. After mice were sacrificed, sections of omentum were excised and fixed in formalin (10%) followed by H&E staining. A–C) WT mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells and treated with PBS. D–F) iPLA2β−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells and treated with PBS. G–I) iPLA2β−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells and treated with LPA. J–L) WT mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8-B6 cells. M–O) iPLA2β−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8-B6 cells. P, pancreas; T, tumor; A, adipose tissue. Scale bars = 100 μm. Images are representative for 3 mice/group.

LPA, but not LPC, stimulates tumorigenesis and ascites formation in iPLA2β−/− mice in vivo

iPLA2β catalyzes hydrolysis of phospholipid substrates to generate a lysophospholipid and a free fatty acid, e.g., AA. As a product, AA can be oxygenated to a variety of bioactive eicosanoids that include prostaglandins (PGs) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs). On measuring the concentrations of these lipids in the tumor environment (peritoneal cavity), we failed to observe significant differences between WT and iPLA2β−/− mice that had not received tumor cell injections. This is consistent with reports that iPLA2β deficiency does not affect lipid levels in many tested organs (13, 14) and with the redundancy of other PLA2 activities in vivo. Intriguingly, after tumor cell injection, significant differences in lipid levels were observed in the peritoneal cavities of WT and knockout mice. Total LPA levels increased by ∼5.9-fold in WT mice on tumor cell injection, but this was not observed in iPLA2β−/− mice (Table 3). Electrospray ionization/MS analyses of individual LPA molecular species revealed that 16:0- and 18:2-LPA levels were ∼11.3- and 9.3-fold higher, respectively, in tumor-challenged WT compared with iPLA2β−/− mice (Table 4). Total LPC levels increased ∼24.7- and 5.7-fold in WT and iPLA2β−/− mice, respectively, on tumor cell injection (Table 3). The levels of individual LPC molecular species were 4.5- to 7.2-fold higher in WT than in iPLA2β−/− mice after tumor challenge (Table 4). Tumor cell injection also produced differential increases in WT compared with iPLA2β−/− mice in other lipid mediators, including free AA (14.8- vs. 4.5-fold), PGs (12.6- vs. 2.0-fold), and HETEs (2.8- vs. 1.4- fold; Table 3). These data indicate that host cell iPLA2β is involved in regulating changes in the accumulation of lipid mediators in the peritoneal space that occur in response to tumor cell injection. The levels of S1P, another bioactive lysophospholipid, were also changed in the same trend as that of LPA (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of lipid analyses in the peritoneal cavity of WT and iPLA2β−/− mice with or without injection of ID8 cells

| Tumor cells and mice | Treatment | Total LPA (μM) | Total LPC (μM) | AA (μM) | HETEs (μM) | PGs (μM) | S1P (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No tumor cellsa | |||||||

| WT, n = 4 | PBS | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 3.95 ± 0.29 | 0.24 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0 |

| iPLA2β−/−, n = 6 | PBS | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 2.55 ± 0.72 | 0.39 ± 0.21 | 0.09 ± 0.05 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0 |

| P | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | |

| ID8 cellsb | |||||||

| WT, n = 6 | PBS | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 97.7 ± 7.23 | 3.62 ± 0.90 | 0.27 ± 0.07 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| iPLA2β−/−, n = 6 | PBS | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 14.5 ± 13.8 | 1.73 ± 1.17 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.04 |

| P | <0.001 | <0.01 | <0.05 | >0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | |

| ID8 cellsc | |||||||

| iPLA2β−/−, n = 6 | LPA | 0.6 ± 0.27 | 114 ± 28.9 | 4.93 ± 1.16 | 0.26 ± 0.16 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.28 ± 0.10 |

| iPLA2β−/−, n = 6 | PBS | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 14.5 ± 13.8 | 1.73 ± 1.17 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 0.04 |

| P | <0.01 | <0.001 | <0.05 | >0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| iPLA2β−/−, n = 7 | LPC | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 13.9 ± 9.79 | 0.34 ± 0.09 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.03 |

Values are means ± se.

Pumps with PBS were placed into WT or iPLA2β−/− mice as described in Table 1 and Materials and Methods. After mice were sacrificed, PBS (2 ml) was used to collect peritoneal washings. After centrifugation, the cell-free washings were used for lipid analysis.

Pumps with PBS were placed into WT or iPLA2β−/− mice that were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells. In 10–12 wk, mice were sacrificed, and ascites were collected and centrifuged for lipid analysis.

Pumps with PBS, LPA (4 mM), or LPC (4 mM) were placed into iPLA2β−/− mice that were intraperitoneally. injected with ID8 cells. In 10–12 wk, mice were sacrificed, and cell-free ascites were collected for lipid analysis.

Table 4.

Fold change of lipid levels in WT and iPLA2β−/− mice challenged with mouse ovarian cancer cells

| Lipid | WT/iPLA2β−/− fold change |

|---|---|

| 16:0 LPA | 11.3 ± 2.9 |

| 18:2 LPA | 9.3 ± 4.9 |

| 18:1 LPA | 4.4 ± 2.5 |

| 18:0 LPA | 4.8 ± 5.0 |

| 20:4 LPA | 4.4 ± 1.8 |

| 22:6 LPA | 2.6 ± 0.9 |

| 14:0 LPC | 5.2 ± 0.9 |

| 16:0 LPC | 7.2 ± 0.9 |

| 18:2 LPC | 5.5 ± 0.2 |

| 18:1 LPC | 5.8 ± 0.3 |

| 18:0 LPC | 8.4 ± 1.03 |

| 20:4 LPC | 4.5 ± 0.1 |

| 20:0 LPC | 7.5 ± 3.0 |

| 22.6 LPC | 6.8 ± 0.6 |

| 22:0 LPC | 7.2 ± 0.4 |

Values are means ± se. Female WT and iPLA2β−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells, and mice were killed in 10–12 wk. Cell-free ascites were collected for lipid analyses. See Materials and Methods for details.

To examine the potential functional roles of individual lysophospholipids, the effects of exogenous LPA or LPC administration into the peritoneal space of iPLA2β−/− mice were determined. LPA, LPC, or PBS was administered via osmotic pump and/or daily intraperitoneal injection for 4 wk after tumor cells were injected. The results indicated that administration of LPA to iPLA2β−/− mice injected with tumor cells strongly enhanced tumorigenesis/metastasis and ascites formation and reduced survival time compared with mice in which PBS was administered (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

Tumor challenge resulted in a rise in peritoneal LPC levels in WT mice that was 6- to 7-fold greater than that in iPLA2β−/− mice. LPC levels also rose in iPLA2β−/− mice infused with LPA to values higher than those achieved in WT mice injected with tumor cells (Table 3), but administration of LPC failed to enhance tumorigenesis/metastasis or to increase LPA levels in either WT or iPLA2β−/− mice (Tables 1 and 3 and Fig. 3) in vivo. This is consistent with the failure of LPC to enhance ID8 cell migration or proliferation in vitro (Fig. 2 and data not shown).

We also compared peritoneal lipid levels in WT and iPLA2β−/− mice injected with ID8-V1 or ID8-B6 cells, which express iPLA2β at higher (endogenous) or lower (down-regulated) levels respectively. Injection of ID8-B6 cells resulted in low levels in measured lipid species (LPA, LPC, AA, HETES, and PGs) (Table 5). Although injection of ID8-V1 cells induced differential rises in LPA, LPC, AA, and PG levels in WT compared with iPLA2β−/− mice (as also observed with the parental ID8 cell line in Tables 2 and 4), injection of ID8-B6 cells did not induce a significant change in the levels of any of these lipids. These observations indicate that tumor cell iPLA2β is also involved in regulating levels of such lipids in vivo.

Table 5.

Summary of lipid analyses in the peritoneal cavity of WT and iPLA2β−/− mice with injection of ID8-V1 or ID8-B6 cells

| Mice and tumor cells | Total LPA (μM) | Total LPC (μM) | AA (μM) | HETEs (μM) | PGs (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | |||||

| ID8-V1 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 88.8 ± 18.1 | 3.0 ± 0.91 | 0.29 ± 0.2 | 0.03 ± 0.02 |

| ID8-B6 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 2.75 ± 1.0 | 0.06 ± 0.16 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 0.01 ± 0.003 |

| P | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| iPLA2β−/− | |||||

| ID8-V1 | 0.40 ± 0.19 | 28.6 ± 9.78 | 1.04 ± 0.41 | 0.12 ± 0.09 | 0.01 ± 0.01 |

| ID8-B6 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 3.04 ± 0.69 | 0.08 ± 0.17 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.004 ± 0.002 |

| P | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.004 |

| P, WT vs. iPLA2β−/− | |||||

| ID8-V1 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| ID8-B6 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.26 | 0.13 |

Values are means ± se. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8-V1 or ID8-B6 cells. In 10–12 wk, mice were sacrificed, and cell-free ascites were collected for lipid analyses.

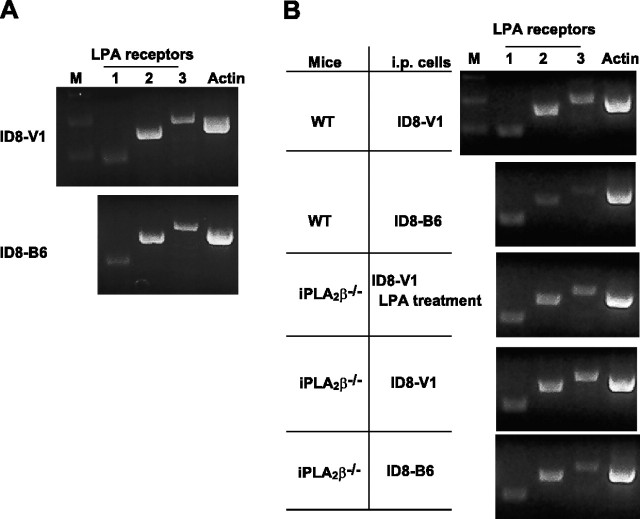

While these data suggest that regulating local lipid concentrations via tumor-host cell interactions is likely to be a major mechanism by which iPLA2β plays roles in EOC development, we cannot rule out other functions of iPLA2β. To test whether it may alter the responsiveness of tumor cells or tissues to LPA, we tested the expression levels of the 3 major LPA receptors (LPA1–3) in ID8-V1 and -B6 cells, as well as omentum tissues obtained from WT and iPLA2β−/− mice injected with ID8-V1 or ID8-B6, along with different treatments. Although there were some alterations among these cells or tissues, no significant changes in the expression levels of these receptors were found (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

iPLA2β did not affect LPA receptors expression in ID8 cells and mouse ovarian cancer. A) RT-PCR was used to detect LPA1–3 expression in ID8-V1 and ID8-B6 cells. B) Omentum tissues were excised from different groups of mice and frozen at −80°C. After mRNA was extracted from the tissue, RT-PCR was used to amplify LPA1–3 receptors. The gene was amplified by 35 cycles. Primer sequence is listed in Materials and Methods.

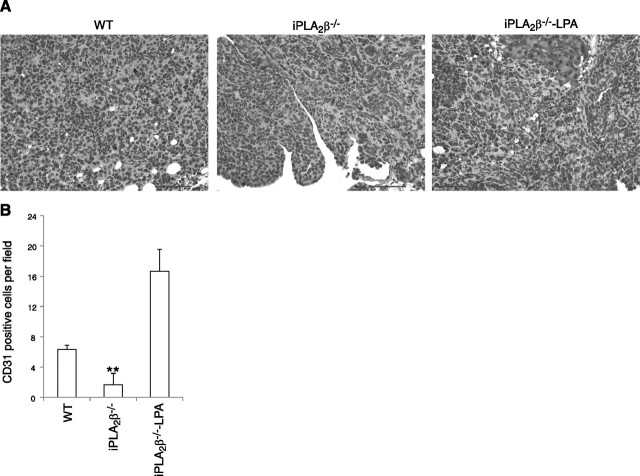

LPA stimulates angiogenesis (33), which is required for progressive tumor growth. CD31 staining of sections from different tumors revealed that ID8 tumors in WT mice exhibited larger numbers of blood vessels at more locations within the tumors than did ID8 tumors in iPLA2β−/− mice, in which blood vessels were confined to the tumor periphery. Administration of exogenous LPA further enhanced angiogenesis in this in vivo model (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Immunostaining of CD31 illustrating LPA regulates angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. A) Tumor tissues were stained with anti-CD31 antibody. Dark color indicates positive staining. Scale bars = 100 μm. B) Quantification of CD31 in different groups (3 mice/group). All mice were intraperitoneally injected with ID8 cells. WT and iPLA2β−/− denote mice treated with PBS; iPLA2β−/−-LPA denotes mice treated with LPA.

DISCUSSION

The iPLA2β-null mice that we have generated have been useful in evaluating potential physiological functions of iPLA2β (9, 13–15, 21, 23), but the potential role of host cell iPLA2β in tumorigenesis has not previously been examined. Our results indicate that iPLA2β in both tumor and host cells participates in EOC development. We have revealed that the absence of iPLA2β in host cells attenuates tumorigenesis, metastasis, and ascites formation induced by EOC cells. In addition, tumor-host cell interactions are required in regulating bioactive lipid levels in tumor microenvironment. This raises the possibility that suppression of iPLA2β expression/activity in both types of cells could be therapeutically beneficial in patients with EOC. In particular, female iPLA2β-null mice are viable and exhibit normal growth and fertility, suggesting that iPLA2β inhibition might not produce clinically significant side effects when it is targeted.

The lack of significant differences in lipid levels in peritoneal cavities of WT and iPLA2β−/− mice in the absence tumor cell challenge is consistent with previous reports that basal lipid profiles are not perturbed in iPLA2β-deficient mice (9, 13, 14), which may reflect redundant roles of various PLA2s in lipid mediator generation in basal physiological settings. After tumor cell injection, however, subsequent tumor development is associated with dramatic changes in the levels of several lipid mediators in the tumor microenvironment, including LPA, LPC, AA, and eicosanoids, that differ between WT and iPLA2β−/− mice. Because the same tumor cell lines were injected into the 2 genotypes, host cells must participate in the changes in lipid mediator levels during tumorigenesis, and these changes cannot be solely attributable to the tumor cells. These results indicate that, although many types of PLA2 may be expressed by various cells in the tumor microenvironment, iPLA2β is specifically involved in regulating the levels of these lipid mediators through tumor-host cell interactions in the vicinity of the tumor. This regulation of iPLA2β could be through either its direct enzymatic activity and/or its indirect lipid modulating activities. The molecular mechanisms by which tumor cells affect host cell iPLA2β remain to be determined. We have measured the levels of several lipid species that could plausibly be affected by iPLA2β, including lysophospholipids, free AA, and oxygenated AA metabolites. Although iPLA2β is an intracellular enzyme, the human EOC cell iPLA2β expression level affects extracellular LPA levels (10). These compounds or their precursors might be produced directly by iPLA2β, but indirect involvement of the enzyme is also possible. It is not yet known whether LPA produced within the cell can be secreted into the extracellular space, but this does occur with other lipid mediators. For example, an ATP-dependent S1P transporter exports S1P produced within cells into the extracellular space (34) and ABCC1 and ABCG2 have been identified as S1P exporters in breast cancer cells (35). S1P and LPA are very similar signaling lysophospholipids, with S1P corresponding to the sphingolipid analog of the glycerolipid LPA from cells, and it is thus plausible that there could be mechanisms for LPA export similar to those for S1P. Alternatively, LPA is known to be produced in the extracellular space from LPC by the lysophoshpholipase D/ATX (36–37), and we have observed a strong correlation between the level of ATX activity in the tumor microenvironment and the extent of tumor development. Positive correlations with ATX activity are observed with tumor size, location, number of loci, and the volume of associated ascites (data not shown). It is possible that iPLA2β influences ATX product generation by substrate provision or other mechanisms that are yet to be identified. We have not identified the cellular source of elevated lipids in vivo, which remains to be further investigated. What has been shown is that both host and tumor cell iPLA2β are involved in regulating these lipid levels.

The host cell types involved in the host-tumor cell interactions need to be further characterized. In addition to mesothelial cells (16), human EOC ascetic fluids are infiltrated with many leukocytes, including immune cells and platelets. Platelets have been suggested to be the major source of serum LPA (38). Activated platelets enhance ovarian cancer cell invasion (39). In addition, Gupat and Massague (40) and Boucharaba et al. (41) have shown that platelet-derived LPA supports the progression of osteolytic bone metastases in breast cancer. Moreover, other host cells, including adipocytes enriched in omentum, may contribute to lipid regulation in the tumor microenvironment. Significant changes in levels of the two lysophospholipids LPA and LPC in the tumor environment occur in our mouse model of tumorigenesis, which are consistent with reports of elevated LPA and LPC levels in human EOC ascites (42–44). Exogenous LPA has been shown to promote EOC development, which correlates well with its effects on cell proliferation, migration, and/or invasion in vitro (22). In addition, LPA may play a protective role in cell survival as in EOC cells (45). In contrast, LPC failed to mimic the effects of LPA in vivo, even though it is a substrate of ATX. There are several possible interpretations for these differences. First, LPC levels in the tumor microenvironment (the peritoneal cavity in our model) are 20 to 100 times higher than that of LPA, and thus, they may not be rate-limiting. Second, our in vitro functional studies suggest that LPC does not a stimulatory activity with ID8 cells, and thus LPC might not be involved in tumorigenesis at the concentrations achieved in our models. Third, it is well known that high concentrations (>10 μM) of LPC in a free form (not bound to a protein) cause cell lysis (46), and this “detergent-like” effect is probably an artifact that is not relevant to in vivo phenomena. In vivo, LPC equilibrates between bound and free forms, and most is bound to carrier proteins, including serum albumin. The inhibitory effects of LPC are largely neutralized by its binding proteins (31). Interestingly, the levels of S1P, another bioactive lipid that may play a role in cancers were also changed in an iPLA2β-depedent manner. Since iPLA2β is not directly involved in S1P production and/or degradation, this may be an indirect effect. We have shown that S1P stimulates cell migration and invasion in human ovarian cancer cells in one of our recent publications (47), and S1P antibody inhibits tumor development in a xenograph model (48). However, when we tested the effects of S1P in vivo in mouse models, we did not observe any stimulatory effect (unpublished results), which is in a sharp contrast to our in vivo LPA experiments. In our studies, LPA has been shown invariably stimulate tumorigenesis and/or metastasis in both immune-comprised and immune-competent mice (22, 24, 25).

Our results suggest that the effects of iPLA2β in ID8 cells are mainly on migration/invasion, while in at least some human cells, it also affected cell proliferation as shown by Song et al. (11). In one of our recently published studies (22), we have shown that while LPA has no significant proliferative effect in ID8 cells, it stimulates proliferation in SKOV3. In addition, iPLA2β plays a role in cell migration and invasion in all of the human ovarian cancer cells tested (10, 16, 28). Thus we believe that the major role of tumor cell iPLA2β is in cell migration and/or invasion. This is not contradictory to the results of Song et al. (11) where the migration/invasion was not tested and the in vivo effects are very likely to be a combinational effect of several iPLA2β cellular effects.

Together, our results suggest that low concentrations of LPC in the free form are unlikely to have a tumorigenesis-promoting role in vivo and LPC bound to proteins may not play a negative role in vivo either. We have observed that exogenous LPA induces a rise in LPC and AA levels in vivo. The mechanism underlying is unknown but may be related to that LPA activates a PLA2 in the tumor microenvironment. This would result in the generation of LPC and AA from PC substrates, and a known precedent for such an effect is the activation of cPLA2α in EOC cells by LPA (16, 28).

Mediators for effects of LPA might include free AA and/or its metabolites, such as PGs. We find that free AA and PGs rise during tumorigenesis to levels that are much higher in WT than in iPLA2β−/− mice (Table 3). These lipids have well-recognized roles in inflammation (49, 50), and inflammation is known to be involved in tumor pathobiology (51). The instability of these lipid mediators complicates direct testing of their effects in vitro, but we (22) have recently demonstrated that cyclooxygenase-1 and 15-lipoxygenase are involved in producing the effects of LPA on human and mouse EOC cells.

Our results including the LPA replenishment data cannot rule out other mechanisms by which iPLA2β affects tumor development. We have tested expression levels of LPA1–3 and did not detect significant changes, suggesting that iPLA2β cannot directly regulate their expression. However, other regulating mechanisms (e.g., sensitize or desensitize the responsiveness of tumor or host cells to LPA) may exist. More in-depth studies remain to be conducted to further understand the mechanisms involved.

We have used intrabursally injected ID8 cells in one of our previous publications (22), which is a better model to distinguish primary tumor growth and metastasis. However, tumor development (primary tumor growth and metastasis) in the intrabursal model is slow, which may be related to the mouse specific bursal structure (which is not present in humans). The intraperitoneal injection model has been well accepted in the ovarian cancer field as an experimental metastasis model closely mimic human late stage disseminating ovarian cancer. In addition, this model has been considered to be the best model up to date for developing potential therapeutics (32, 52).

In summary, we describe several novel observations here that include demonstrations that iPLA2β expressed both by host and tumor cells is important for tumorigenesis in immunocompetent mice; that host cell iPLA2β is involved in regulating lipid mediator levels in the tumor microenvironment; and that LPA and LPC exert quite different effects on EOC development in vivo. These findings suggest that the iPLA2β-LPA pathway represents an attractive target for designing novel therapeutic interventions that might be beneficial in treating patients with EOC, which is among the most lethal and difficult to treat of human malignancies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by U.S. National Institutes of Health grant RO1 CA095042, an Indiana University Cancer Center Translational Research Acceleration Collaboration grant, and the Mary Fendrich Hulman Charitable Trust (to Y.X.). It was also supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants R37-DK-34388, P41-RR-00954, P60-DK-20579, R37-DK-34388, and P30-DK-56341 (to J.T). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sengupta S., Wang Z., Tipps R., Xu Y. (2004) Biology of LPA in health and disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. , 503–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu Y., Sengupta S., Singh S., Steinmetz R. (2006) Novel lipid signaling pathways in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Sci. Rev. , 168–197 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mills G. B., Moolenaar W. H. (2003) The emerging role of lysophosphatidic acid in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer , 582–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murph M. M., Liu W., Yu S., Lu Y., Hall H., Hennessy B. T., Lahad J., Schaner M., Helland A., Kristensen G., Borresen-Dale A. L., Mills G. B. (2009) Lysophosphatidic acid-induced transcriptional profile represents serous epithelial ovarian carcinoma and worsened prognosis. PLoS ONE , e5583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aoki J., Inoue A., Okudaira S. (2008) Two pathways for lysophosphatidic acid production. Biochim. Biophys. Acta , 513–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balsinde J., Balboa M. A., Insel P. A., Dennis E. A. (1999) Regulation and inhibition of phospholipase A2. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. , 175–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudo I., Murakami M. (1999) [Phospholipase A2]. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso , 1013–1024 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudo I., Murakami M. (2002) Phospholipase A2 enzymes. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. , 3–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramanadham S., Yarasheski K. E., Silva M. J., Wohltmann M., Novack D. V., Christiansen B., Tu X., Zhang S., Lei X., Turk J. (2008) Age-related changes in bone morphology are accelerated in group VIA phospholipase A2 (iPLA2beta)-null mice. Am. J. Pathol. , 868–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X., Wang D., Zhao Z., Xiao Y., Sengupta S., Xiao Y., Zhang R., Lauber K., Wesselborg S., Feng L., Rose T. M., Shen Y., Zhang J., Prestwich G., Xu Y. (2006) Caspase-3-dependent activation of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 enhances cell migration in non-apoptotic ovarian cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. , 29357–29368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song Y., Wilkins P., Hu W., Murthy K. S., Chen J., Lee Z., Oyesanya R., Wu J., Barbour S. E., Fang X. (2007) Inhibition of calcium-independent phospholipase A2 suppresses proliferation and tumorigenicity of ovarian carcinoma cells. Biochem. J. , 427–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bissell M. J., Weaver V. M., Lelievre S. A., Wang F., Petersen O. W., Schmeichel K. L. (1999) Tissue structure, nuclear organization, and gene expression in normal and malignant breast. Cancer Res. , 1757–1763s; discussion 1763s–1764s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bao S., Miller D. J., Ma Z., Wohltmann M., Eng G., Ramanadham S., Moley K., Turk J. (2004) Male mice that do not express group VIA phospholipase A2 produce spermatozoa with impaired motility and have greatly reduced fertility. J. Biol. Chem. , 38194–38200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bao S., Song H., Wohltmann M., Ramanadham S., Jin W., Bohrer A., Turk J. (2006) Insulin secretory responses and phospholipid composition of pancreatic islets from mice that do not express group VIA phospholipase A2 and effects of metabolic stress on glucose homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. , 20958–20973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao S., Bohrer A., Ramanadham S., Jin W., Zhang S., Turk J. (2006) Effects of stable suppression of group VIA phospholipase A2 expression on phospholipid content and composition, insulin secretion, and proliferation of INS-1 insulinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. , 187–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren J., Xiao Y. J., Singh L. S., Zhao X., Zhao Z., Feng L., Rose T. M., Prestwich G. D., Xu Y. (2006) Lysophosphatidic acid is constitutively produced by human peritoneal mesothelial cells and enhances adhesion, migration, and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. , 3006–3014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shen Z., Belinson J., Morton R. E., Xu Y., Xu Y. (1998) Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate stimulates lysophosphatidic acid secretion from ovarian and cervical cancer cells but not from breast or leukemia cells. Gynecol. Oncol. , 364–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eder A. M., Sasagawa T., Mao M., Aoki J., Mills G. B. (2000) Constitutive and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-induced LPA production: role of phospholipase D and phospholipase A2. Clin. Cancer Res. , 2482–2491 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fang X., Yu S., Bast R. C., Liu S., Xu H. J., Hu S. X., LaPushin R., Claret F. X., Aggarwal B. B., Lu Y., Mills G. B. (2004) Mechanisms for lysophosphatidic acid-induced cytokine production in ovarian cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. , 9653–9661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chou C. H., Wei L. H., Kuo M. L., Huang Y. J., Lai K. P., Chen C. A., Hsieh C. Y. (2005) Up-regulation of interleukin-6 in human ovarian cancer cell via a Gi/PI3K-Akt/NF-kappaB pathway by lysophosphatidic acid, an ovarian cancer-activating factor. Carcinogenesis , 45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran J. M., Buller R. M., McHowat J., Turk J., Wohltmann M., Gross R. W., Corbett J. A. (2005) Genetic and pharmacologic evidence that calcium-independent phospholipase A2beta regulates virus-induced inducible nitric-oxide synthase expression by macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. , 28162–28168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H., Wang D., Zhang H., Kirmani K., Zhao Z., Steinmetz R., Xu Y. (2009) Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates cell migration, invasion, and colony formation as well as tumorigenesis/metastasis of mouse ovarian cancer in immunocompetent mice. Mol. Cancer Ther. , 1692–1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bao S., Jin C., Zhang S., Turk J., Ma Z., Ramanadham S. (2004) Beta-Cell Calcium-independent group VIA phospholipase A(2) (iPLA(2)beta): tracking iPLA(2)beta movements in response to stimulation with insulin secretagogues in INS-1 cells. Diabetes (Suppl. 1), S186–S189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim K. S., Sengupta S., Berk M., Kwak Y. G., Escobar P. F., Belinson J., Mok S. C., Xu Y. (2006) Hypoxia enhances lysophosphatidic acid responsiveness in ovarian cancer cells and lysophosphatidic acid induces ovarian tumor metastasis in vivo. Cancer Res. , 7983–7990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sengupta S., Kim K. S., Berk M. P., Oates R., Escobar P., Belinson J., Li W., Lindner D. J., Williams B., Xu Y. (2007) Lysophosphatidic acid downregulates tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases, which are negatively involved in lysophosphatidic acid-induced cell invasion. Oncogene , 2894–2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Z., Xu Y. (2010) An extremely simple method for extraction of lysophospholipids and phospholipids from blood samples. J. Lipid Res. , 652–659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao Z., Xu Y. (2009) Measurement of endogenous lysophosphatidic acid by ESI-MS/MS in plasma samples requires pre-separation of lysophosphatidylcholine. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. , 3739–3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sengupta S., Xiao Y. J., Xu Y. (2003) A novel laminin-induced LPA autocrine loop in the migration of ovarian cancer cells. FASEB J. , 1570–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hazen S. L., Zupan L. A., Weiss R. H., Getman D. P., Gross R. W. (1991) Suicide inhibition of canine myocardial cytosolic calcium-independent phospholipase A2. Mechanism-based discrimination between calcium-dependent and -independent phospholipases A2. J. Biol. Chem. , 7227–7232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balsinde J., Dennis E. A. (1996) Bromoenol lactone inhibits magnesium-dependent phosphatidate phosphohydrolase and blocks triacylglycerol biosynthesis in mouse P388D1 macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. , 31937–31941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu Y., Xiao Y. J., Zhu K., Baudhuin L. M., Lu J., Hong G., Kim K. S., Cristina K. L., Song L., F S. W., Elson P., Markman M., Belinson J. (2003) Unfolding the pathophysiological role of bioactive lysophospholipids. Curr. Drug Targets Immune Endocr. Metabol. Disord. , 23–32 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bast R. C., Hennessy B., Mills G. B. (2009) The biology of ovarian cancer: new opportunities for translation. Nat. Rev. Cancer , 415–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teo S. T., Yung Y. C., Herr D. R., Chun J. (2009) Lysophosphatidic acid in vascular development and disease. IUBMB Life , 791–799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kobayashi N., Yamaguchi A., Nishi T. (2009) Characterization of the ATP-dependent sphingosine 1-phosphate transporter in rat erythrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. , 21192–21200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takabe K., Kim R. H., Allegood J. C., Mitra P., Ramachandran S., Nagahashi M., Harikumar K. B., Hait N. C., Milstien S., Spiegel S.. Estradiol induces export of sphingosine 1-phosphate from breast cancer cells via ABCC1 and ABCG2. J. Biol. Chem. , 10477–10486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tokumura A., Majima E., Kariya Y., Tominaga K., Kogure K., Yasuda K., Fukuzawa K. (2002) Identification of human plasma lysophospholipase D, a lysophosphatidic acid-producing enzyme, as autotaxin, a multifunctional phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. , 39436–39442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Umezu-Goto M., Kishi Y., Taira A., Hama K., Dohmae N., Takio K., Yamori T., Mills G. B., Inoue K., Aoki J., Arai H. (2002) Autotaxin has lysophospholipase D activity leading to tumor cell growth and motility by lysophosphatidic acid production. J. Cell Biol. , 227–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eichholtz T., Jalink K., Fahrenfort I., Moolenaar W. H. (1993) The bioactive phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid is released from activated platelets. Biochem. J. , 677–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holmes C. E., Levis J. E., Ornstein D. L. (2009) Activated platelets enhance ovarian cancer cell invasion in a cellular model of metastasis. Clin. Exp. Metastasis , 653–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupta G. P., Massague J. (2004) Platelets and metastasis revisited: a novel fatty link. J. Clin. Invest. , 1691–1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boucharaba A., Serre C. M., Gres S., Saulnier-Blache J. S., Bordet J. C., Guglielmi J., Clezardin P., Peyruchaud O. (2004) Platelet-derived lysophosphatidic acid supports the progression of osteolytic bone metastases in breast cancer. J. Clin. Invest. , 1714–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu Y., Gaudette D. C., Boynton J. D., Frankel A., Fang X. J., Sharma A., Hurteau J., Casey G., Goodbody A., Mellors A., Hobub B. J., Mills G. B. (1995) Characterization of an ovarian cancer activating factor in ascites from ovarian cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. , 1223–1232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao Y., Chen Y., Kennedy A. W., Belinson J., Xu Y. (2000) Evaluation of plasma lysophospholipids for diagnostic significance using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analyses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. , 242–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xiao Y. J., Schwartz B., Washington M., Kennedy A., Webster K., Belinson J., Xu Y. (2001) Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry analysis of lysophospholipids in human ascitic fluids: comparison of the lysophospholipid contents in malignant vs nonmalignant ascitic fluids. Anal. Biochem. , 302–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee Z., Swaby R. F., Liang Y., Yu S., Liu S., Lu K. H., Bast R. C., Mills G. B., Fang X. (2006) Lysophosphatidic acid is a major regulator of growth-regulated oncogene alpha in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. , 2740–2748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Corven E. J., Groenink A., Jalink K., Eichholtz T., Moolenaar W. H. (1989) Lysophosphatidate-induced cell proliferation: identification and dissection of signaling pathways mediated by G proteins. Cell , 45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang D., Zhao Z., Caperell-Grant A., Yang G., Mok S. C., Liu J., Bigsby R. M., Xu Y. (2008) S1P differentially regulates migration of human ovarian cancer and human ovarian surface epithelial cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. , 1993–2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmid G., Guba M., Ischenko I., Papyan A., Joka M., Schrepfer S., Bruns C. J., Jauch K. W., Heeschen C., Graeb C. (2007) The immunosuppressant FTY720 inhibits tumor angiogenesis via the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1. J. Cell. Biochem. , 259–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vargaftig B. B., Zirinis P. (1973) Platelet aggregation induced by arachidonic acid is accompanied by release of potential inflammatory mediators distinct from PGE2 and PGF2. Nat. New Biol. , 114–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hyde C. A., Missailidis S. (2009) Inhibition of arachidonic acid metabolism and its implication on cell proliferation and tumour-angiogenesis. Int. Immunopharmacol. , 701–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gil O. D., Lee C., Ariztia E. V., Wang F. Q., Smith P. J., Hope J. M., Fishman D. A. (2008) Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) promotes E-cadherin ectodomain shedding and OVCA429 cell invasion in an uPA-dependent manner. Gynecol. Oncol. , 361–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merritt W. M., Lin Y. G., Spannuth W. A., Fletcher M. S., Kamat A. A., Han L. Y., Landen C. N., Jennings N., De Geest K., Langley R. R., Villares G., Sanguino A., Lutgendorf S. K., Lopez-Berestein G., Bar-Eli M. M., Sood A. K. (2008) Effect of interleukin-8 gene silencing with liposome-encapsulated small interfering RNA on ovarian cancer cell growth. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. , 359–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]