Abstract

The human intestine harbors a large number of microbes forming a complex microbial community that greatly affects the physiology and pathology of the host. In the human gut microbiome, the enrichment in certain protein gene families appears to be widespread. They include enzymes involved in carbohydrate metabolism such as glucoside hydrolases of dietary polysaccharides and glycoconjugates. We report the crystal structures (wild type, 2 mutants, and a mutant/substrate complex) and the enzymatic activity of a recombinant α-glucosidase from human gut bacterium Ruminococcus obeum. The first ever protein structures from this bacterium reveal a structural homologue to human intestinal maltase-glucoamylase with a highly conserved catalytic domain and reduced auxiliary domains. The α-glucosidase, a member of GH31 family, shows substrate preference for α(1–6) over α(1–4) glycosidic linkages and produces glucose from isomaltose as well as maltose. The preference can be switched by a single mutation at its active site, suggestive of widespread adaptation to utilization of a variety of polysaccharides by intestinal micro-organisms as energy resources.—Tan, K., Tesar, C., Wilton, R., Keigher, L., Babnigg, G., Joachimiak, A. Novel α-glucosidase from human gut microbiome: substrate specificities and their switch.

Keywords: substrate selection and switch, glycoside hydrolase, GH31 family, isomannose binding, carbohydrate metabolism

The human gastrointestinal microbiota influence the physiology and health of their host (1–4). Recently large-scale metagenomic sequence analyses of the gut microbiota have been performed to understand species composition, diversity, core functions, and distribution along the gastrointestinal tract, as well as their adaptation to the human intestinal environment (5, 6). Although the majority of microbes are still uncharacterized and the functions of many sequenced and predicted genes are to be assigned, initial studies have shown that the gut microbial community plays a critical role in host maturation (2, 7), development of the immune system (8, 9), and production and regulation of essential biochemical compounds (3, 10). Numerous diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes, have been associated with the interruption of microbiota functions or signal pathways (11). It has been also reported that the gut microbiota are a contributing factor in whole body glucose homeostasis (12). The analysis of completed genomes of gut microbiota also shows the significant enrichment of certain genes that include those involved in carbohydrate and amino acid transport and metabolism (13). It is commonly thought that the colonic microbiota utilize otherwise indigestible polysaccharides and peptides as primary resources for energy production and biosynthesis of cellular components.

Ruminococcus obeum is a member of the Firmicutes division of the domain bacteria. The Firmicutes, together with the Bacteroidetes, make up the majority of phylogenetic types in the human distal gut microbiota (14). A few studies on samples from small intestine contents (15) and small intestine mucosa (16) also found microbiota (though less dense) in each compartment of the human small intestine, including the jejunum. Species belonging to Firmicutes, Fusobacterium, Bacteroidetes, or γ-Proteobacteria were among the most abundant (17). As in many other gut species, in the genome of R. obeum ATCC 29174, the genes belonging to the “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” category are strongly represented with 256 genes, as classified by the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COGs) of proteins database. This corresponds to >10% of the total protein genes to which COG has been assigned (http://www.jgi.doe.gov) (18). Within the 256 genes, 35 have been predicted to be members of the glycoside hydrolase (GH) family (Supplemental Table S1) (http://www.cazy.org) (19), which is involved in the degradation of carbohydrate polymers (20). However, thus far the function of these genes and encoded proteins has not been confirmed. We have selected a “probable” α-glucosidase [RUMOBE_03919, COG1501, family 31 of glycoside hydrolases (GH31)] for structural and functional studies. We have determined and analyzed crystal structures of wild-type, 2 mutants, and a mutant/substrate complex, and performed enzymatic assays and site-directed mutagenesis to understand the roles of the key active site residues in catalysis and substrate specificity. For the convenience of following discussion, we named the R. obeum enzyme α-glucosidase as Ro-αG1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein cloning, expression, and purification

The α-glucosidase gene from R. obeum ATCC 29174 was cloned into the pMCSG19 vector and overexpressed in Escherichia coli pRK1037. The cells were grown at 37°C in selenomethionine (SeMet) containing enriched M9 medium under conditions known to inhibit methionine biosynthesis (21). The SeMet-labeled protein was purified from the E. coli cells using Ni-affinity chromatography as described previously (22). The protein was concentrated using Centricon (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) in 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0 buffer, 250 mM NaCl, and 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The final protein yield was ∼11 mg/L culture. Site-direct mutations D73A, D307A, D420A, and W169Y were created by the PIPE cloning method (23). The plasmid mentioned above was used as the template, primers were added to a final concentration of 0.4 μM, and mutagenesis was performed in a final volume of 50 μl using PfuUltra Hotstart PCR Master Mix (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The procedure from the subsequent transformation of PCR products to mutant expression and purification was the same as described above for the wild-type enzyme. Plasmids of mutants were sequenced for confirmation.

Size exclusion chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography was performed on a Superdex-200 10/300GL column using FPLC (GE Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The column was pre-equilibrated with crystallization buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT) and calibrated with premixed protein standards, including ribonuclease A (13.7 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), conalbumin (75 kDa), aldolase (158 kDa), ferritin (440 kDa), and blue dextran (2000 kDa). A 200 μl protein sample at 4.7 mg/ml was injected into the column. The chromatography was carried out at room temperature at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. The calibration curve of Kav vs. log molecular weight was prepared using the equation Kav = Ve − Vo/Vt − Vo, where Ve = elution volume for the protein, Vo = column void volume, and Vt = total bed volume.

Protein crystallization

The SeMet labeled Ro-αG1 was screened for crystallization conditions with the help of the Mosquito liquid dispenser (TTP Labtech, Cambridge, MA, USA) using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion technique in 96-well CrystalQuick plates (Greiner Bio-one, Monroe, NC, USA). For each condition, 0.4 μl of protein (33 mg/ml) and 0.4 μl of crystallization formulation were mixed; the mixture was equilibrated against 135 μl of the reservoir in the well. Three crystallization screens were used: Index (Hampton Research, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA), ANL-1 (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and ANL-2 (Qiagen) at both 24 and 4°C. Diffraction quality crystals appeared under the condition of 0.1 M Bis-Tris pH 5.5, 25% (w/v) PEG3350 at 4°C. The crystals belong to monoclinic space group P21 with cell dimensions a = 68.9 Å, b = 125.0 Å, c = 88.6 Å, β = 107.7°, and diffracted X-rays to 2.02 Å resolution. Wild-type and D73A, D307A, D420A, and W169Y mutants were cocrystallized with maltose and isomaltose in different protein/substrate molar ratios, using the hanging drop vapor diffusion technique in 24-well VDX plates (Hampton Research). Crystals of diffraction quality were obtained for D73A and D307A mutants in the presence of maltose (protein/substrate molar ratio of 1:10) and for D307A mutant with elevated isomaltose concentration (protein/substrate molar ratio of 1:200). All crystals had the same space group and similar unit cell parameters (Table 1). Prior to data collection, crystals of wild-type Ro-αG1 and D73A and D307A mutants were treated with cryoprotectant (10% glycerol) added to crystallization buffer and were frozen directly in liquid nitrogen. Crystals of D307A mutant cocrystallizaed with isomaltose were cryoprotected with 300 mM (∼10.3%) isomaltose.

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Parameter | Wild type | D73A | D307A | D307A/isomaltose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||||

| Space group | P21 | P21 | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell (Å, deg) | a = 68.9, b = 125.0, c = 88.6, β = 107.7 | a = 64.2, b = 122.5, c = 87.5, β = 108.6 | a = 64.8, b = 124.0, c = 87.8, β = 108.2 | a = 68.4, b = 125.5, c = 87.9, β = 107.8 |

| MW (Da; residue) | 77,083; 663a | 77,039; 663a | 77,039; 663a | 77,039; 663a |

| Mol (AU) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| SeMet (AU) | 54 | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9793 (peak) | 0.9795 | 0.9795 | 0.9793 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 35.2–2.02 (2.02–2.06) | 82.9–2.65 (2.65–2.70) | 49.8–2.90 (2.90–2.97) | 41.4–1.92 (1.92–1.95) |

| Unique reflections | 93,200b | 36,535 | 29,095 | 107,674 |

| Redundancy | 4.6 (4.4) | 3.5 (3.4) | 4.5 (4.0) | 3.7 (2.9) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.6) | 99.5 (99.4) | 99.2 (94.1) | 99.4 (93.2) |

| Rmerge (%) | 14.9 (64.4) | 14.3 (74.2) | 13.8 (79.4) | 8.2 (64.0) |

| I/σ | 14.0 (2.2) | 8.8 (1.5) | 10.9 (1.4) | 15.8 (1.4) |

| Phasing | ||||

| RCullis, anomalous (%) | 85 | |||

| Figure of merit (%) | 20.3 | |||

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution | 43.9–2.02 | 82.9–2.65 | 49.8–2.90 | 41.4–1.92 |

| Reflections, work/test | 88,427/4655 | 34,687/1825 | 27,591/1481 | 102,259/5381 |

| Rcrystal/Rfree (%) | 16.8/20.6 | 18.9/25.8 | 22.2/29.7 | 17.2/21.8 |

| Rms deviation from ideal geometry, bond length (Å)/angle (deg) | 0.012/1.267 | 0.015/1.535 | 0.013/1.479 | 0.012/1.291 |

| Protein atoms | 10,923 | 10,677 | 10,735 | 10,873 |

| Cyro/water molecules | 2/830 | 1/52 | 0/0 | 2/913 |

| Mean B value, mainchain/sidechain (Å2) | 13.8/15.9 | 36.3/37.6 | 54.5/55.3 | 11.1/12.6 |

| Ramachandran plot statistic, residues (%) | ||||

| Most favored regions | 88.9 | 85.4 | 81.7 | 88.5 |

| Additional allowed regions | 10.7 | 14.3 | 17.9 | 11.0 |

| Generously allowed regions | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Disallowed region | 0.1c | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Numbers in parentheses are values for the highest-resolution bin.

Not including cloning artifact.

Including Bijvoet pairs.

Residue K422 of each monomer is located in a sharp turn and well defined in electron density maps. In a Ramachandran plot, it is within the boundary of a generously allowed region and disallowed region.

X-ray diffraction and structure determination

For the initial determination of the wild-type crystal structure, a set of single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) data was collected near the selenium absorption peak at 100 K from a single SeMet-labeled crystal. The data were obtained at the 19-ID beamline of the Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory using the program SBCcollect. The intensities were integrated and scaled with the HKL3000 suite (24) (Table 1). Two molecules with a total of 54 methionine residues were expected in one asymmetric unit. Heavy atom sites were located using the program SHELXD (25), and 50 selenium sites were used for phasing with the program MLPHARE (26). To improve map quality, a noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS) was identified with 46 selenium sites out of 50 related by 2-fold NCS. After map averaging and density modification (26), a partial model of 1244 residues (93% of a dimer) with 1211 side chains was built in 3 cycles of ARP/wARP (27) model building. All of the above programs are integrated within the program suite HKL3000 (24). Further model buildings to complete the structure were performed manually using the program COOT (28). The final model was refined using the program REFMAC (29) (Table 1). For 3 mutant structures, single-wavelength data sets were collected. Their structures were solved by using the program MolRep (30). After model rebuilding and refinement, the structures of these mutants were found to be similar to the wild-type structure described above. The data, structure determination, and refinement and model statistics are provided in Table 1. For the D73A and D307A mutants crystallized in the presence of maltose, neither maltose nor maltose hydrolysis product (glucose) were identified in the structure. For D307A mutant crystallized in presence of high-concentration isomaltose (∼10%), a clear electron density was observed for one unit of glucose (nonreducing end), and partial electron density was observed for the second unit of glucose (reducing end) in isomaltose at each of 2 active sites of Ro-αG1 dimer (see below).

Glucose assay

The Glucose Assay Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to determine the substrate specificity of Ro-αG1 and mutants. Production of glucose was measured following reaction of the enzymes with various substrates. Reactions were carried out in duplicate by incubating 10–100 nM enzyme with 30 mM substrate for 30–60 min at 37°C (in 50 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl, pH 6.5). Reactions were quenched by heating for 3 min at 95°C and were developed with glucose oxidase/peroxidase (GO) reagent containing 1 mM acarbose (see below) for 60 min at 37°C. The reactions were quenched with 6 M sulfuric acid, and optical density was measured at 535 nm with a Dynex Triad Multimode microplate reader (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA, USA). The amount of substrate hydrolyzed was quantitated by a standard curve for glucose. The results were factored for production of 2 mol of glucose per mole of maltose or isomaltose. Larger polysaccharides were assumed to produce 1 mol glucose/mol substrate, based on the assumption of initial rate and excess substrate conditions. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 4.03 for Windows (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA; http://www.graphpad.com).

During the course of our experiments we observed a high background signal in the GO assays when maltose was the substrate. This was found to be due to contaminating maltase activity that was present in the GO reagent. Maltases are common contaminants of glucose oxidase preparations (31). We determined that acarbose, a glycoside hydrolase inhibitor, added to the GO reagent significantly reduced the background maltase activity. Acarbose (Sigma), at a final concentration of 1 mM, was added to the GO reagent, and the mixture was incubated on ice for 1 h prior to start of the glucose assay.

RESULTS

Overall structure of Ro-αG1 wild type

The recombinant Ro-αG1 was expressed in E. coli and purified using affinity chromatography. The protein crystallized in the monoclinic space group P21 with two 663-residue monomers in one asymmetric unit. The 2 monomers are related by a 2-fold axis (Fig. 1A). The structure was determined using the SAD approach and SeMet-labeled crystal and refined to 2.02 Å resolution. The electron density maps are excellent, and the structure is of high quality with 99.6% residues in most favored and additional allowed regions of Ramachandran plot statistics (Table 1). Each monomer consists of 4 domains: a β-sandwich N-terminal domain (residues 1-138), a catalytic (β/α)8-barrel domain (residues 163-522), a β-sandwich proximal C-terminal domain (residues 525-609), and a degenerated β-sandwich distal C-terminal domain (residues 610-663). The 2 monomers in the asymmetric unit form a dimer with a noncrystallographic 2-fold axis, which is consistent with the size-exclusion chromatography data (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the molecule also exists as a dimer in solution. The dimerization interface is quite extensive (see below) and involves a number of interactions using several domains and secondary structure elements (see below). Within the catalytic domain there are 2 prominent inserts, insert 1 (Ins1) and insert 2 (Ins2) (Fig. 1A). The α-helical hairpin of the Ins2 from each monomer forms a 4-helix bundle, helping bridge 2 monomers together. In terms of overall multidomain architecture, each monomer of Ro-αG1 is similar to that of 3 GH31 family members (20) with known crystal structures, including the N-terminal subunit of human maltase-glucoamylase (NtMGAM, PDB ID 2QLY) (32), thermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus α-glucosidase MalA (PDB ID 2G3M) (33), and E. coli α-xylosidase YicI (PDB ID 1XSK) (34). From sequence similarity and signature in the nucleophile region (WIDMNE), Ro-αG1 together with NtMGAM and MalA can be further classified into subgroup 1 of GH31 family, whereas YicI is classified into subgroup 4 with a different signature sequence (KTDFGE) (33). Ro-αG1 is the first bacterial member of subgroup 1 of the GH31 family. However, this enzyme displays several unique structural features that make it distinct.

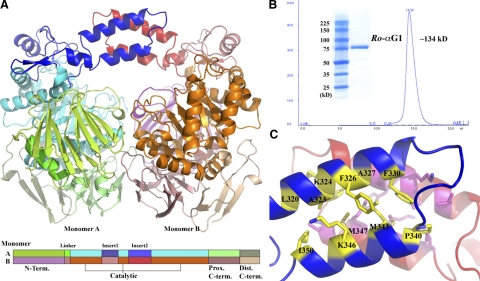

Figure 1.

The Ro-αG1 dimer. A) Ribbon drawing shows 2 monomers related by a pseudo-2-fold. Each monomer consists of a β-sandwich N-terminal domain, a catalytic (β/α)8-barrel domain, a proximal C-terminal domain, and a degenerated distal C-terminal domain. There are 2 prominent inserts within the catalytic domain, insert 1 and insert 2. The α-helical hairpin of insert 2 from 2 monomers forms a 4-helix bundle that bridges the 2 monomers and is the major contributing factor of the core structure of the dimer interface. B) Size-exclusion chromatography of Ro-α-G1. Based on a calibration curve, the protein mass correspondent to the α-glucosidase elution volume is estimated to be 134 kD, nearly 2 times that of the calculated molecular mass of the enzyme. Insert: SDS-PAGE of Ro-αG1, showing its apparent molecular mass of ∼75 kD. C) Hydrophobic core structure of the 4-helix bundle. Residues contributing to the formation of the 4-helix bundle are drawn in stick format and colored differently, yellow or magenta for monomers A and B, respectively. For clarity, only residues from the α-helix hairpin of monomer A are labeled.

Dimerization

The total buried solvent-accessible area due to the dimer formation is ∼4954 Å2. The N-terminal domain, the main body of the catalytic domain, and the proximal C-terminal domain together contribute ∼3475 Å2, while the 4-helix bundle alone contributes ∼1479 Å2, or ∼30% of the total buried solvent-accessible area. The distal C-terminal domain and the Ins1 of the catalytic domain do not contribute surfaces to the dimer. The nature of the interactions provided by the N-terminal domain, the main body of the catalytic domain, and the proximal C-terminal domain, which contribute a large portion of the dimer interface, is largely hydrophilic with 40 hydrogen bonds and 13 salt bridges across the dimer interface. There are also numerous water molecules residing in the interface and forming an extensive hydrogen bond network between 2 monomers. In contrast, the dimer interface provided by the 4-helix bundle is predominantly hydrophobic with only 4 hydrogen bonds (the interaction of 2 K324 residues with 4 main chain carbonyl groups; Fig. 1C). The Gibbs free energy of the α-glucosidase dimer formation is −18.6 kcal/mol, in which the formation of the 4-helix bundle contributes −13.1 kcal/mol. This suggests that the 4-helix bundle plays an important role in the enzyme's dimer stabilization. The 4 helix-bundle motif is widely found in subunit interfaces and in the core structures of many proteins (35).

Catalytic domain

The catalytic domain is of a (β/α)8-barrel fold that is the most common in enzymes and is found in many glycoside hydrolases (19, 36). The active site of the domain is located on the C-terminal face of the central β-barrel (Fig. 2A). Between the β3c-strand and the α3c-helix, there is an insert (Ins1, residues N237-I281) of ∼35 amino acids. The second insert (Ins2, residues E309-N371) is between the β4c-strand and the α4c-helix and is more prominent. Both inserts (Ins1 and Ins2) are well structured and contain several secondary structure elements (Fig. 2A). The 3 short β-strands from Ins1 (β1I1, β2I1, and β3I1) and the first strand from Ins2 (β1I2) form a mini antiparallel β-sheet (β1I1↓, β3I1↑, β2I1↓ and β1I2↑). The α-helix (α1I1) between β1I1 and β2I1 is antiparallel to the α3c-helix of the (β/α)8-barrel. In Ins2, the β1I2-strand is followed by the α-helical hairpin comprised of α1I2 and α2I2, which is followed by a β-hairpin formed by β2I2 and β3I2. The β-hairpin is hydrogen bonded to the turn between the α1I1 and β2I1 of Ins1.

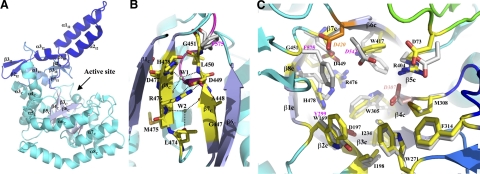

Figure 2.

Catalytic domain and active site. A) Catalytic domain of Ro-αG1. The enzyme's active site is at the C-terminal opening of the (β/α/)8-barrel. The 8 β-strands of the (β/α)8-barrel are colored light blue to highlight their location. All α-helices and β-strands of the 2 inserts are labeled. For clarity, only a part of the secondary structures of the (β/α)8-barrel that are in the view are labeled. B) The (β/α)8-barrel is “broken” between the β7 and β8-strands. There is no mainchain-mainchain hydrogen bond between these 2 parallel β-strands. Instead, 2 water molecules (W1 and W2) reside between them and mediate multiple hydrogen bonds bridging the 2 strands. A salt-bridge between D449 of β7c-strand and R476 of β8c-strands is a primary sidechain-sidechain interaction between these 2 strands. In human NtMGAM and S. solfolobus MalA, there is a kink after the β7c-strand (magenta), which shifts the structural alignment of G451 of the apo Ro-αG1 to F575 instead of G573 of NtMGAM. In the D307A/isomaltose complex structure of Ro-αG1, as discussed in this work, the same kink was found after the β7c-strand with F453 in the same position of F575 of NtMGAM. C) Comparison of the active sites of Ro-αG1 and NtMGAM. All the residues contributing to the active site are drawn in stick format, with the carbon atoms mostly colored in yellow. Residue D307 (purple) is possibly the catalytic nucleophile. Residue D420 (orange) is possibly the acid/base catalyst. Green loop where the conserved aspartic acid (D73 in Ro-αG1) resides at the top right corner is from the N-terminal domain. Based on structural alignment, the correspondent residues from Ro-αG1 and NtMGAM are D73/D203, W169/Y299, D197/D327, I198/I328, I234/I364, W271/W406, W305/W441, D307/D443, M308/M444, F314/F450, R404/R526, W417/W539, D420/D542, D449/D571, R476/R598, and H478/H600, respectively. Residues of NtMGAM are colored light gray for their carbon atoms. For clarity, only those residues that are either different in sequence or have a major conformational difference are labeled in magenta.

The 2 inserts interact with each other and with the (β/α)8-barrel as well, seemingly providing a well-structured platform to present the long α-helical hairpin protruding from the main body of the protein to the opposite monomer. Another feature of the (β/α)8-barrel is that the internal β-barrel is “broken” between β7C and β8C (Fig. 2B). There is no mainchain-mainchain interaction between the 2 parallel strands. Instead, there are 2 water molecules (W1 and W2) between them, forming multiple hydrogen bonds to each of the strands. In addition, one salt-bridge between the D449 of the β7C and the R476 of β8C helps zip the 2 strands inside the barrel (Fig. 2C); both of these residues are highly conserved. The functional significance of the β-barrel buckle is unknown. Interestingly, the sequence motif D449LGGF seems to be very conserved (Fig. 3).

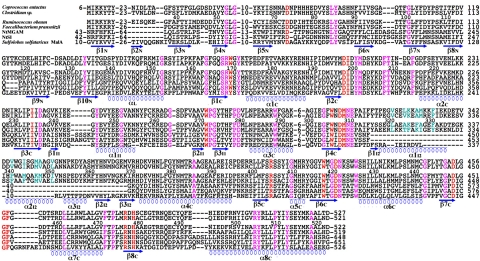

Figure 3.

Multiple sequence and structural alignment. Primary amino acid sequences of the N-terminal domain and the catalytic domain including inserts were initially aligned using the program Clustalw. The alignment generated 3 groups of sequences: 1) α-glucosidases from Coprococcus eutactus ATCC 27759 (gi:163815929), Clostridium sp. L2–50 (gi:160893051), R. obeum ATCC 29174 (gi:15381349), and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii M21/2 (gi:160943368); 2) human NtMGAM (gi: 221316699) and NtSI (gi: 157364974; 3) S. solfataricus MalA (gi: 3912992). The alignment of the 3 groups was then modified based on the structural alignment of Ro-αG1, NtMGAM, and S. solfataricus MalA. Sequence numbering of Ro-αG1 is marked above the sequence for the discussion in the text. Identical residues are highlighted in magenta. Active site residues are colored red. Residues that form the core of the 4-helix bundle in the α-glucosidases from group 1 are colored cyan.

Active site

Although the sequence identity of the catalytic domains of Ro-αG1 and NtMGAM is less than 30%, the residues that form their active sites are highly conserved in both their primary sequences and their conformations (D73, D197, D307, D420, D449, and R76) (Figs. 2C and 3). D307 is presumably the catalytic nucleophile, based on the experimental data on its equivalent in NtMGAM (37) and α-xylosidase YicI (34). D420 has been proposed as an acid/base catalyst (32). One exception is G451; in both NtMGAM and MalA the corresponding residue is phenylalanine. The other sequence substitution in the active site is W169. In NtMGAM and MalA, it is a tyrosine. It has been observed that the human N-terminal subunit of sucrase-isomaltase (NtSI), which preferably cleaves the isomaltose α(1–6) linkage, also has a tryptophan at this position (Fig. 3). Since both NtMGAM and MalA show higher specificity for the maltose α(1–4) linkage than isomaltose, W169 may provide substrate specificity. In the active site, the residue D73 from the N-terminal domain is unique, and it seems to be a conserved feature of the GH31 family, as it is also present in NtMGAM and MalA, as well as in the α-xylosidase YicI (Fig. 3). D73 is located on the long loop between the β5N and β6N strands of the N-terminal domain. This loop protrudes from the N-terminal domain and crosses over the β5C-strand of the (β/α)8-barrel (Fig. 2C). The β5C-strand is a relatively short strand in the β-barrel, seemingly permitting the pass of the loop to present the aspartic acid at the active site.

N- and C-terminal β-sandwich domains

Unlike NtMGAM, which has an extra N-terminal trefoil type-P domain followed by β-sandwich domain, Ro-αG1 starts with a relatively shorter N-terminal β-sandwich domain (Fig. 4A), which is comprised of 10 antiparallel β-strands (β1N↑β10N↓β7N↑β6N↓β4N↑/β2N↑β3N↓β9N↑ β8N↓β5N↑). The domain is similar to the N-terminal domain of MalA but is one N-terminal strand shorter (Fig. 3). Comparison of NtMGAM, MalA and Ro-αG1 shows that the first half of the N-terminal domain is more variable in both of their sequences and structures than the second half of the domain (Figs. 3 and 4A). The second half of the domain is closely packed onto the catalytic domain. As discussed earlier, one long and conserved loop (β5N_β6N in Ro-αG1) protrudes toward the catalytic domain and positions D73, which is highly conserved, at the active site.

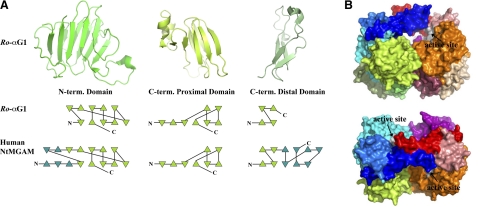

Figure 4.

The N- and C-terminal domains and molecular surface representative of Ro-αG1. A) The N- and C-terminal β-sandwich domains of Ro-αG1 and their comparison to the corresponding domains of human NtMGAM. The extra β-strands in NtMGAM are colored differently (cyan) in their topological representations. B) Molecular surface representative of the Ro-αG1 dimer. Surface is colored according to the color codes for the ribbon diagram in Fig. 1A. surface areas contributed by the residues that form the active sites shown in Fig. 2C are colored light gray. Top panel: side view of the dimer in the same orientation as that of the dimer in Fig. 1A. Bottom panel: top view. Arrows indicate active sites under the 4-helix bundle.

The proximal C-terminal domain is the most conserved β-sandwich domain in these α-glucosidases (Fig. 4A). Their sequence identity is ∼30%, and their sizes are similar without any major insertions or deletions. Most of the domain is buried due to its packing with other domains and its contribution to the dimerization of Ro-αG1. The buried surface of the proximal C-terminal domain is ∼60% of its total surface area. The distal C-terminal domain of Ro-αG1 is much shorter than that of NtMGAM, MalA, and YicI. The domain has little contact with the catalytic domain and contributes little to the dimerization as discussed earlier.

Substrate specificity and functional roles of key residues

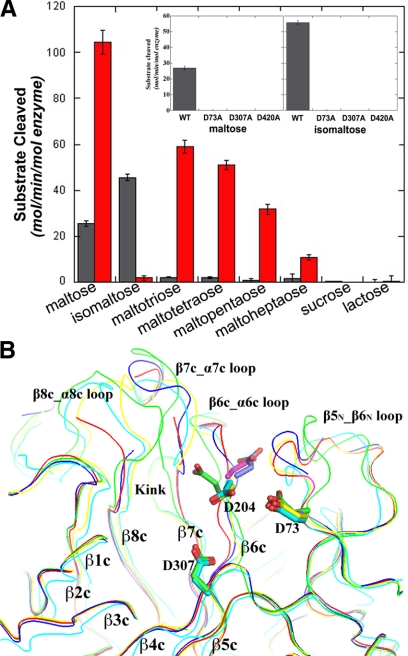

Ro-αG1 does not hydrolyze sucrose or lactose, indicating no specific activities against the α(1–2) or β(1–4) glycosidic bonds (Fig. 5A). Ro-αG1 shows highest activity with isomaltose [α(1–6) linkage] and somewhat lower (∼60%) activity with maltose [α(1–4) linkage]. Thus, Ro-αG1 shows preference for isomaltose over maltose but can hydrolyze both (Fig. 5A). The mutant W169Y reversed this preference, suggesting the aromatic residue W169 at the active site is part of a selectivity determinant of isomaltose and maltose. Under the assay conditions used for these experiments, substitution of the presumed catalytic nucleophile D307 or the presumed acid/base catalyst D420 with alanines abolished the hydrolytic capability of the enzyme. Another intriguing result is that the D73A mutation also eliminated enzymatic activity. D73 is the only residue in the active site that is from the N-terminal domain. There also seems to be a strong restriction on the size of glucose oligomers that can be hydrolyzed. Ro-αG1 shows low activity with maltotriose, maltotetraose, maltopentaose, and maltoheptatose (Fig. 5A). Although the W169Y mutant, with its preference for maltose, shows increased activity with these maltodextrins compared to the wild-type enzyme, hydrolytic activity clearly decreases with increased maltodextrin length.

Figure 5.

Substrate specificity of wild-type and mutants and their structural alignment. A) Substrate specificity of Ro-αG1 wild-type (gray) and W169Y mutant (red). Enzymes were incubated with 30 mM of the indicated substrate in 50 mM MES, 100 mM NaCl, pH 6.5. The enzyme concentration in the W169Y/maltose reaction was reduced to 10 nM to maintain glucose production within the linear range of the assay. For the other reactions, the enzyme concentration was 100 nM. Production of glucose was measured with the glucose oxidase assay. Insert: α-glucosidase activity of wild-type and 3 aspartate mutants against maltose and isomaltose (see text for details). B) Structural alignment of the active sites of Ro-αG1 wild-type (green), D307A (blue) and D73A (red) mutants, and D307A/isomaltose complex (yellow) with human NtMGAM/acarbose (cyan). The 8 β-strands are labeled at the C-terminal opening of the (β/α/)8-barrel of catalytic domain to assist in locating the loop after each strand. In the D307A structure, most of the β8c_α8c loop is disordered with a broken trace. In the D73A structure, part of the β7c_α7c loop and most of the β8c_α8c loop are disordered. Large conformational variation occurs to the β6c_α6c loop, the β7c_α7c loop, and the β8c_α8c loop as well as the β5N_β6N loop, showing their structural flexibility. The 3 key residues, D73, D307, and D420 of Ro-αG1, and their equivalent residues of NtMGAM are drawn in the stick format. The D307A/isomaltose complex is aligned better with the NtMGAM/acarbose complex than the apo form of its wild-type and 2 mutants. A kink after β7c strand is found only in the 2 complex structures. Large conformational change seemingly occurs after substrate binding to these glucosidases.

The structures of D307A, D73A, and D307A/isomaltose complex

We have also determined the crystal structures of 2 mutants, D307A and D73A, without any ligand bound. Unexpectedly, significant conformational changes were observed in the active site and its surroundings (Fig. 5B). The β6c_α6c loop, the β7c_α7c loop, and the β5N_ β6N loop from the N-terminal domain where the residue D73 is located have the most conformational changes compared to that in the wild-type structure. Moreover, in the D307A structure the majority of the β8c_α8c loop is disordered. In the D73A mutant structure, part of the β7c_α7c loop and most of β8c_α8c loop are disordered.

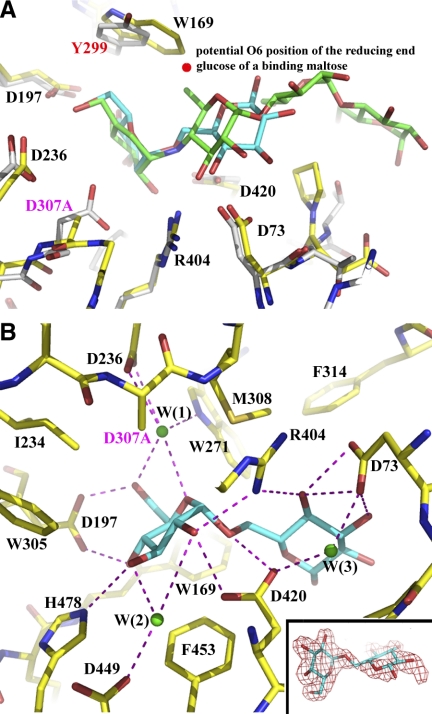

In the presence of a high concentration of isomaltose (∼10%), a crystal of D307A/isomaltose complex was obtained, and its structure was determined. In this high-resolution structure, the active site conformational variations associated with the β6c_α6c loop, the β7c_α7c loop, the β8c_α8c loop, and the β5N_ β6N loop were also observed compared to the wild-type structure and the D307A mutant structure (Fig. 5B). Surprisingly, these loops, together with other parts of the “active” site of the inactive D307A mutant, can be structurally aligned very well with their counterparts of the human NtMGAM (Fig. 6A). This includes the kink that is absent in the apo Ro-αG1 structure (Fig. 2B) and now is present in the structure of the complex with isomaltose. Interestingly the F575 of NtMGAM is now aligned with the F453 of Ro-αG1 instead of the G451 in the apo Ro-αG1 structure (Fig. 2C). The observation suggests that these loops contributing to the active site in apo Ro-αG are quite flexible. However, when a substrate is bound, they assume a common conformation, indicating similar substrate binding modes of human NtMGAM and Ro-αG1.

Figure 6.

Substrate or inhibitor binding at active site. A) Comparison of the active sites of the 2 structures, D307A/isomaltose of Ro-αG1 and NtMGAM/acarbose. Active site residues of Ro-αG1 and the isomaltose are drawn in stick format, and their carbon atoms are drawn in yellow and cyan, respectively. Carbon atoms of NtMGAM and acarbose are drawn in silver and green, respectively. The highly conserved active site residues are almost in the same conformation in the 2 structures. When a maltose is modeled into the binding site (not shown in the figure for clarity), the O6 atom of the reducing end glucose is approximately in the position marked by a magenta dot. B) The hydrogen bond pattern at the active site of D307A/isomaltose. Three water molecules located at the active site are drawn in small spheres and in green. All hydrogen bonds are drawn with magenta dashed lines. Insert: electron density map (2Fo-Fc) associated with the isomaltose at the 1σ contour level.

The isomaltose binding at the “active” site of the inactive D307A mutant (Fig. 6) is indeed similar, in many aspects, to what was observed in the human NtMGAM/acarbose complex (32). At the −1 sugar-binding site (38), the nonreducing end glucose of the isomaltose hydrogen bonds with D197, R404, H478, and the proposed acid/base catalyst D420, as well as 2 water molecules W(1) and W(2). All these interactions have their equivalents in the NtMGAM/acarbose complex including water-mediated hydrogen bonds such as the one involved with D449 (32). The residue W169 that can switch the substrate preference by being substituted to a Tyr as described earlier is interacting with the nonreducing end and the glycosidic bond between 2 glucose units (Fig. 6B). The primary difference at the−1 sugar-binding site in the D307A/isomaltose structure compared to the NtMGAM/acarbose complex is related to the D307A mutation of the presumed catalytic nucleophile. In the NtMGAM/acarbose complex, the equivalent catalytic nucleophile interacts with the −1 subsite through a water molecule that is equivalent to W(1) (Fig. 6B). At the +1 sugar-binding site, the residue D73 that is from the N-terminal domain forms 2 hydrogen bonds to the reducing end glucose of isomaltose. There is also a hydrogen bond contributed by R404 to the +1 subsite. D73 also makes a water-mediated hydrogen bond with D420 that hydrogen bonds to nonreducing end glucose. This arrangement therefore provides a sensing mechanism for the substrate and distinguishes it from binding glucose, the product of the reaction. All these interactions are well conserved in the structure of NtMGAM/acarbose complex (32). In addition, other conserved residues, mostly aromatic, such as W271, W305, M308, F314, F453, contribute to the formation of the substrate-binding site. The interaction pattern between the “active” site of D307A and isomaltose indicate that the D307A/isomaltose complex largely represents the interaction between the wild-type Ro-αG1 and its substrate isomaltose.

Sequence homologs in human microbiome bacteria

Analysis of genome sequences revealed the closest homologs of the enzyme Ro-αG1 in other gut firmicutes (Ruminococcus, Coprococusi, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium) (Supplemental Material). In this highly related set of 28 proteins, 11% of residues are identical, including all active site residues. When extending the homology to a minimal bit-score of 300, more than 130 homologs are identified adding additional firmicutes, such as Lactobacillus, Eubacterium, Listeria, all part of a recent human gut metagenome survey (6). This family shows 59 residues with high conservation. Lowering a bit-score cutoff to 100 expands the family to nearly 1400 members with 9 highly conserved residues (D73, D307, R404, W417, G419, D420, D449, G452, and H478). All of these conserved residues are part of the active site (Fig. 2C). The specificity switch W169 diverges at the bit-score cutoff value of 300 and is replaced with Y169 in one-third of the cases. The analysis of the 3.3 million unique protein sequences of the human gut metagenome survey (6) revealed 93 homologs of Ro-αG1 using a minimal bit-score cutoff value of 300. In this dataset, 96% of the sequences have a tryptophan and 4% a phenylalanine corresponding to W169. The specificity switch occurs at the bit-score cutoff value of 100.

In addition, human gut microbes have a number of glucoside hydrolases. A survey of completed genomes showed that the commensal Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron has more than 350 glucoside hydrolases, followed by R. obeum and Lactobacillus lactis having nearly 35 ORFs belonging to this family (Supplemental Table S2). In E. coli, depending on the strain, the number of glucoside hydrolases can vary from 42 (E. coli K-12) to less than 5 (E. coli O157:H7), showing similar trends with other pathogenic gut microbes (e.g., Shigella). We identified around 1400 glucoside hydrolases from the 3.5 million unique protein sequences of the ∼1000 genomes available from NCBI, half of which is part of the 2 Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron genomes. Within this set GH31 family members account for 2.6% of all glycoside hydrolases. In contrast, we have identified more than 58,000 glycoside hydrolases from the 3.3 million unique protein sequences of the recent human gut metagenome survey (6), of which 4.5% are part of the GH31 family (Supplemental Table S3).

DISCUSSION

The enrichment of genes involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism has been observed in human gut bacterium genome analysis. Based on COG categories, the genes predicted to be involved in carbohydrate transport and metabolism are commonly more than 10% of the genes annotated. This is in great contrast to the percentage (∼5–6%) of the genes classified in the same category for other bacteria. Although there are few functional studies of these genes or gene products, it is widely believed that host nondigestible food components serve as sources of energy and carbon for the human gut bacteria. However, the great catalytic potential of these gut bacteria genes on carbohydrates will not be fully appreciated without experimental examination.

Ro-αG1, the only known member of GH31 found in this bacterium, is one of 35 predicted GH members. It is unknown how much the capability of the enzyme and its homologs from other bacteria for processing isomaltose, maltose, and maltodextrin could impact food digestion and absorption in the small intestine or other physiological or pathological processes in gastrointestinal system. The functionality of these enzymes on carbohydrate hydrolysis and glucose uptake needs to be further investigated. The whole maltose system, including transport, metabolism, and regulation of maltose/maltodextrin, is unknown in the gram-positive R. obeum. Based on current knowledge of its genome, there are a number of carbohydrate ABC (ATP-binding cassette) transporters annotated for R. obeum (14), including genes with homology to the components of a maltose transporter system, the 2 membrane-integral subunits (MalF and MalG), ABC subunit (MalK), and a maltose-binding protein (MalE) (39).

We have attempted to identify the structural determinants of substrate specificity and catalytic efficiency. As discussed earlier, the conformation of the active sites and the hydrogen bond patterns in the structures of NtMGAM/acarbose and D307A/isomaltose of Ro-αG1 are very conserved (Fig. 6A). The major variation between NtMGAM [preference for α(1–4) linkage] and Ro-αG1 [preference for α(1–6) linkage] in their active sites is the Y299 (NtMGAM) vs. W169 (Ro-αG1). In the NtMGAM/acarbose complex, Y299 forms a part of −1 sugar-binding site with no hydrogen bond to the inhibitor acarbose (32). When a maltose (its preferred substrate) is bound at the active site, the O6 atom from the reducing end glucose will point to the Y299 and potentially form a hydrogen bond with the Oη atom of the Y299 (Fig. 6C). However, if the tyrosine is replaced by a tryptophan, such as W169 in the Ro-αG1 structure, the larger sidechain of the Trp could limit the positioning of the O6 atom at the same site. The α(1–6) linkage between the 2 glucose units of an isomaltose seemingly avoids any conflicts with the Trp. These observations could explain why isomaltose is preferred over maltose by Ro-αG1 (Fig. 6A). The NtSI, which preferably cleaves the isomaltose α(1–6) linkage, also has a tryptophan at this position (Fig. 3). The W/Y site seems to be a switching site for substrate specificity in a large number of GH31 family members. Our experimental data support this notion because W169Y mutant switches the substrate preference of Ro-αG from isomaltose [α(1–6)] to maltose [α(1–4)]. We propose that a residue at this site (a tyrosine or a tryptophan) largely controls the substrate specificity of these glycoside hydrolases. A residue at the switching site doesn't seem to be able to completely exclude one substrate from the other. This is also consistent with our observation that Ro-αG1 activity with maltose is still ∼60% of that with isomaltose. It is possible that the lower substrate specificity of Ro-αG1-like glucosidases is a strategy that the bacteria have adapted to utilize multiple sugar substrates.

Compared to the D307A/isomaltose structure, the large conformational variation of the β6c_α6c loop, the β7c_α7c loop, the β8c_α8c loop, and the β5N_ β6N loop observed in the structures of wild-type and D307A and D73A mutants (Fig. 5B) suggests the structural flexibility of part of the active site of the apo glucosidase. This may be another strategy for multiple sugar sources.

The functions of the β-sandwich domain are unknown in the GH31 family. Structural homologs of the N-terminal domain of Ro-αG1 can be found in many structures from carbohydrate-active enzymes such as the N-terminal domain of the E. coli glucosidase YgjK (PDB:3D3I) (40), a member of glycoside hydrolase family 63 (GH63). Their similar topologies imply that the Ro-αG1 N-terminal domain may bind carbohydrate substrates as in YgjK. The β-sandwich domain is generally recognized as playing the role of carbohydrate binding (41) and may help position polysaccharides to approach the catalytic domain.

Another potential role of the N-terminal domain is the regulation of the activity of the enzyme. The residue D73 in the active site is the only residue that is not from the catalytic domain; the D73 located on a protruding loop from the N-terminal domain is highly conserved. The aspartic acid in both NtMGAM/acarbose and D307A/isomaltose involve substrate binding in the +1 sugar-binding site, contributing 2 or more than 2 direct hydrogen bonds to the subunit of binding molecule at the +1 subsite. The aspartic acid is also conserved in the structure of E. coli α-xylosidase YicI and involved in substrate binding (34). The D73A mutant of Ro-αG1 shows no hydrolytic activity toward either isomaltose or maltose, suggesting it is required for the α-glucosidase activity. In fact, this residue contributes to an aspartate triangle together with the presumed catalytic nucleophile D307 and acid/base catalyst D420 on one side of the active site (Fig. 2C). A mutation in any of these residues abolishes glucosidase activity.

The quaternary structures of human NtMGAM, S. solfataricus MalA, Ro-αG1, and even E. coli YicI are different. MGAM is a type 1 membrane protein with NtMGAM proximate to the membrane. Although NtMGAM is physiologically linked to CtMGAM (another GH31 domain), NtMGAM is functionally monomeric, unlike MalA and YicI, which form hexamers, a dimer of trimers, and a trimer of dimers, respectively. Whether the quaternary structures of these enzymes play functional roles remains to be explored. It is generally believed that oligomerization can help to increase stability, lead to multivalency, and increase local concentration of active centers.

In the Ro-αG1 dimer, the 2 active sites are solvent exposed, but reside right under the 4-helix bundle (Fig. 4B). The 4-helix bundle helps bridge 2 monomers to form a dimer. It also seemingly restricts the access to the 2 active sites beneath for long linear substrates. This may explain why Ro-αG1 has very low hydrolytic activity against maltose oligosaccharides. It may also be the very reason that the 4-ring acarbose is not a good inhibitor for Ro-αG1 (data not shown). The W169Y mutant greatly increased the activity for maltose, but the activity for the maltose oligosaccharides decreased quickly with the increase of the number of glucose units.

In summary, the substrate specificity (both isomaltose and maltose) of the Ro-αG1 suggests that the gut bacterium can potentially uptake digestible carbohydrates directly from the intestine and produce glucose. The glucose metabolism pathways in the human gut microbiome need to be further explored to understand their potential impact to human physiology of glucose metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Structural Biology Center at Argonne National Laboratory for their help with data collection at the 19-ID beamline. The authors also thank Lindsey Butler for help in the preparation of this manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM074942 and by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The atomic coordinates and structural factors of the wild-type Ro-aG1, D73A, and D307 mutants and D307/isomaltose complex have been deposited in the PDB databank under accession codes 3N04, 3M46, 3M6D, and 3MKK, respectively. The submitted manuscript has been created by UChicago Argonne, LLC, Operator of Argonne National Laboratory (“Argonne”). Argonne, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, is operated under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The U.S. Government retains for itself, and others acting on its behalf, a paid-up nonexclusive, irrevocable worldwide license in said article to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hooper L. V., Bry L., Falk P. G., Gordon J. I. (1998) Host-microbial symbiosis in the mammalian intestine: exploring an internal ecosystem. BioEssays 20, 336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper L. V., Gordon J. I. (2001) Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut. Science 292, 1115–1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaut M., Clavel T. (2007) Metabolic diversity of the intestinal microbiota: implications for health and disease. J. Nutr. 137, 751S–755S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ventura M., O'Flaherty S., Claesson M. J., Turroni F., Klaenhammer T. R., van Sinderen D., O'Toole P. W. (2009) Genome-scale analyses of health-promoting bacteria: probiogenomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 61–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turnbaugh P. J., Hamady M., Yatsunenko T., Cantarel B. L., Duncan A., Ley R. E., Sogin M. L., Jones W. J., Roe B. A., Affourtit J. P., Egholm M., Henrissat B., Heath A. C., Knight R., Gordon J. I. (2009) A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457, 480–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin J., Li R., Raes J., Arumugam M., Burgdorf K. S., Manichanh C., Nielsen T., Pons N., Levenez F., Yamada T., Mende D. R., Li J., Xu J., Li S., Li D., Cao J., Wang B., Liang H., Zheng H., Xie Y., Tap J., Lepage P., Bertalan M., Batto J. M., Hansen T., Le Paslier D., Linneberg A., Nielsen H. B., Pelletier E., Renault P., Sicheritz-Ponten T., Turner K., Zhu H., Yu C., Jian M., Zhou Y., Li Y., Zhang X., Qin N., Yang H., Wang J., Brunak S., Doré J., Guarner F., Kristiansen K., Pedersen O., Parkhill J., Weissenbach J., Bork P., Ehrlich S. D.A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stappenbeck T. S., Hooper L. V., Gordon J. I. (2002) Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 15451–15455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazmanian S. K., Liu C. H., Tzianabos A. O., Kasper D. L. (2005) An immunomodulatory molecule of symbiotic bacteria directs maturation of the host immune system. Cell 122, 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh V., Singh K., Amdekar S., Singh D. D., Tripathi P., Sharma G. L., Yadav H. (2009) Innate and specific gut-associated immunity and microbial interference. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 55, 6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill M. J. (1997) Intestinal flora and endogenous vitamin synthesis. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 6, S43–S45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mai V., Draganov P. V. (2009) Recent advances and remaining gaps in our knowledge of associations between gut microbiota and human health. World J. Gastroenterol. 15, 81–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Membrez M., Blancher F., Jaquet M., Bibiloni R., Cani P. D., Burcelin R. G., Corthesy I., Macâe K., Chou C. J. (2008) Gut microbiota modulation with norfloxacin and ampicillin enhances glucose tolerance in mice. FASEB J. 22, 2416–2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurokawa K., Itoh T., Kuwahara T., Oshima K., Toh H., Toyoda A., Takami H., Morita H., Sharma V. K., Srivastava T. P., Taylor T. D., Noguchi H., Mori H., Ogura Y., Ehrlich D. S., Itoh K., Takagi T., Sakaki Y., Hayashi T., Hattori M. (2007) Comparative metagenomics revealed commonly enriched gene sets in human gut microbiomes. DNA Res. 14, 169–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckburg P. B., Bik E. M., Bernstein C. N., Purdom E., Dethlefsen L., Sargent M., Gill S. R., Nelson K. E., Relman D. A. (2005) Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308, 1635–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi H., Takahashi R., Nishi T., Sakamoto M., Benno Y. (2005) Molecular analysis of jejunal, ileal, caecal and recto-sigmoidal human colonic microbiota using 16S rRNA gene libraries and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism. J. Med. Microbiol. 54, 1093–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M., Ahrné S., Jeppsson B., Molin G. (2005) Comparison of bacterial diversity along the human intestinal tract by direct cloning and sequencing of 16S rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 54, 219–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Booijink C. C., Zoetendal E. G., Kleerebezem M., de Vos W. M. (2007) Microbial communities in the human small intestine: coupling diversity to metagenomics. Future Microbiol. 2, 285–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markowitz V. M., Chen I. M., Palaniappan K., Chu K., Szeto E., Grechkin Y., Ratner A., Anderson I., Lykidis A., Mavromatis K., Ivanova N. N., Kyrpides N. C. (2009) The integrated microbial genomes system: an expanding comparative analysis resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D382–D390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–D238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Henrissat B., Davies G. (1997) Structural and sequence-based classification of glycoside hydrolases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 7, 637–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Duyne G. D., Standaert R. F., Karplus P. A., Schreiber S. L., Clardy J. (1993) Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J. Mol. Biol. 229, 105–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim Y., Dementieva I., Zhou M., Wu R., Lezondra L., Quartey P., Joachimiak G., Korolev O., Li H., Joachimiak A. (2004) Automation of protein purification for structural genomics. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 5, 111–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klock H. E., Lesley S. A. (2009) The Polymerase Incomplete Primer Extension (PIPE) method applied to high-throughput cloning and site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 498, 91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minor W., Cymborowski M., Otwinowski Z., Chruszcz M. (2006) HKL-3000: the integration of data reduction and structure solution: from diffraction images to an initial model in minutes. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider T. R., Sheldrick G. M. (2002) Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CCP4 (1994) The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen S. X., Morris R. J., Fernandez F. J., Ben Jelloul M., Kakaris M., Parthasarathy V., Lamzin V. S., Kleywegt G. J., Perrakis A. (2004) Towards complete validated models in the next generation of ARP/wARP. Acta Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2222–2229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vagin A., Teplyakov A. (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dahlqvist A. (1961) Determination of maltase and isomaltase activities with a glucose-oxidase reagent. Biochem. J. 80, 547–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sim L., Quezada-Calvillo R., Sterchi E. E., Nichols B. L., Rose D. R. (2008) Human intestinal maltase-glucoamylase: crystal structure of the N-terminal catalytic subunit and basis of inhibition and substrate specificity. J. Mol. Biol. 375, 782–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ernst H. A., Lo Leggio L., Willemoèes M., Leonard G., Blum P., Larsen S. (2006) Structure of the Sulfolobus solfataricus alpha-glucosidase: implications for domain conservation and substrate recognition in GH31. J. Mol. Biol. 358, 1106–1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lovering A. L., Lee S. S., Kim Y. W., Withers S. G., Strynadka N. C. (2005) Mechanistic and structural analysis of a family 31 alpha-glycosidase and its glycosyl-enzyme intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 2105–2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin S. L., Tsai C. J., Nussinov R. (1995) A study of four-helix bundles: investigating protein folding via similar architectural motifs in protein cores and in subunit interfaces. J. Mol. Biol. 248, 151–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerlt J. A., Raushel F. M. (2003) Evolution of function in (beta/alpha)8-barrel enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 252–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nichols B. L., Avery S., Sen P., Swallow D. M., Hahn D., Sterchi E. (2003) The maltase-glucoamylase gene: common ancestry to sucrase-isomaltase with complementary starch digestion activities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 1432–1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies G. J., Wilson K. S., Henrissat B. (1997) Nomenclature for sugar-binding subsites in glycosyl hydrolases. Biochem. J. 321, 557–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheffel F., Fleischer R., Schneider E. (2004) Functional reconstitution of a maltose ATP-binding cassette transporter from the thermoacidophilic gram-positive bacterium Alicyclobacillus acidocaldarius. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1656, 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kurakata Y., Uechi A., Yoshida H., Kamitori S., Sakano Y., Nishikawa A., Tonozuka T. (2008) Structural insights into the substrate specificity and function of Escherichia coli K12 YgjK, a glucosidase belonging to the glycoside hydrolase family 63. J. Mol. Biol. 381, 116–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boraston A. B., Bolam D. N., Gilbert H. J., Davies G. J. (2004) Carbohydrate-binding modules: fine-tuning polysaccharide recognition. Biochem. J. 382, 769–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.