Abstract

In the outer layers of the dorsal cochlear nucleus, a cerebellum-like structure in the auditory brain stem, multimodal sensory inputs drive parallel fibers to excite both principal (fusiform) cells and inhibitory cartwheel cells. Cartwheel cells, in turn, inhibit fusiform cells and other cartwheel cells. At the microcircuit level, it is unknown how these circuit components interact to modulate the activity of fusiform cells and thereby shape the processing of auditory information. Using a variety of approaches in mouse brain stem slices, we investigated the synaptic connectivity and synaptic strength among parallel fibers, cartwheel cells, and fusiform cells. In paired recordings of spontaneous and evoked activity, we found little overlap in parallel fiber input to neighboring neurons, and activation of multiple parallel fibers was required to evoke or alter action potential firing in cartwheel and fusiform cells. Thus neighboring neurons likely respond best to distinct subsets of sensory inputs. In contrast, there was significant overlap in inhibitory input to neighboring neurons. In recordings from synaptically coupled pairs, cartwheel cells had a high probability of synapsing onto nearby fusiform cells or other nearby cartwheel cells. Moreover, single cartwheel cells strongly inhibited spontaneous firing in single fusiform cells. These synaptic relationships suggest that the set of parallel fibers activated by a particular sensory stimulus determines whether cartwheel cells provide feedforward or lateral inhibition to their postsynaptic targets.

INTRODUCTION

Anatomical and physiological studies of neuronal circuits have revealed much about sources of inputs, targets of outputs, classes of constituent neurons, and broad patterns of synaptic connectivity. At a finer level, however, far less is understood about the distribution of synaptic connections onto and between individual neurons and how these connections shape the activity of postsynaptic neurons and circuit output (Silberberg et al. 2005). Lack of this level of circuit information has limited our understanding of computations in the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN), an auditory brain stem structure that integrates multimodal sensory inputs, generating output important for orienting the head toward sounds (May 2000; Sutherland et al. 1998).

The general features of the DCN circuitry are well established (for review, see Oertel and Young 2004). Inputs are anatomically divided, with tonotopically arranged auditory nerve afferents delivering sound information to the DCN deep layer (Osen 1970), and somatosensory, proprioceptive, and descending auditory inputs synapsing onto a cerebellum-like system of granule cells that project parallel fiber axons throughout the molecular layer, the outermost layer of the DCN (Mugnaini et al. 1980b; Ryugo et al. 2003; Shore and Zhou 2006). The somata of fusiform cells, the main output neurons of the DCN, are sandwiched between the deep and molecular layers, permitting fusiform cells to receive excitatory auditory nerve, and possibly ventral cochlear nucleus T stellate cell, input on their basal dendrites and parallel fiber input on their apical dendrites (Doucet and Ryugo 1997; Oertel et al. 1990; Smith and Rhode 1985). Fusiform cells also receive input from several classes of inhibitory interneurons (Rubio and Juiz 2004). Among these are cartwheel cells, molecular layer interneurons that receive parallel fiber input and possess local axons that synapse onto fusiform cells and other cartwheel cells (Berrebi and Mugnaini 1991; Golding and Oertel 1997; Mancilla and Manis 2009; Manis et al. 1994; Mugnaini 1985; Roberts et al. 2008).

In vivo studies indicate that both parallel fibers and cartwheel cells adjust the firing rate of fusiform cells, presumably modulating how fusiform cells respond to auditory inputs (Davis and Young 1997, 2000; Davis et al. 1996). Nevertheless, it is unclear how parallel fibers drive activity at the microcircuit level and what role cartwheel cell-mediated inhibition plays in shaping the effects of this activity on fusiform cells. Here we investigate the synaptic relationships among individual parallel fibers, cartwheel cells, and fusiform cells. Using dual recordings, we find that individual parallel fibers are unlikely to synapse onto neighboring neurons and that input from multiple parallel fibers is required to drive changes in cartwheel and fusiform cell firing. Additional experiments show that neighboring pairs of neurons receive inhibitory input from multiple common presynaptic neurons and that inhibition from individual cartwheel cells strongly inhibits spontaneous firing in postsynaptic fusiform cells. The sparse distribution of parallel fiber synaptic contacts and the broad distribution of inhibitory synaptic contacts suggest that cartwheel cells may employ lateral inhibition to narrow the range of sensory inputs that excite fusiform cells. When stimuli broadly activate parallel fibers, however, cartwheel cells may provide feedforward inhibition, limiting the time window for synaptic integration in fusiform cells.

METHODS

Transgenic mice

A colony of transgenic GFP-expressing interneurons (GIN) mice, in which GFP expression is driven by the promoter for the GABA-synthetic enzyme GAD67 (Oliva et al. 2000), was maintained as previously described (Roberts et al. 2008). These mice were used to facilitate the identification of cartwheel cells. The nontransgenic littermates of GIN mice were frequently used in experiments, and no differences in DCN physiology were found between slices prepared from transgenic versus nontransgenic mice. All procedures were conducted according to OHSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Slice electrophysiology

Coronal, 210-μm-thick, brain stem slices containing the DCN were prepared from P17-23 hemizygous GIN mice or their nontransgenic littermates. Slices were cut in 34°C artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) and then incubated at the same temperature for 1 h prior to use in experiments. Except where noted, ACSF was composed of (in mM) 130 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2.4 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.2 KH2PO4, 20 NaHCO3, 3 Na-HEPES, and 10 glucose; bubbled with 5% CO2-95% O2; osmolality: ∼305 mOsm. For some experiments, the ACSF was modified to better represent physiological K+, free Ca2+, and Mg2+ concentrations (Davson and Segal 1996). This was accomplished by adjusting KCl to 2.1 mM (total [K+] = 3.3 mM), CaCl2 to 1.7 mM, and MgSO4 to 1.0 mM. Where noted, inhibitory synaptic transmission was blocked by adding 0.5 μM strychnine and 20 μM SR95531 (gabazine) to the ACSF, and excitatory transmission was blocked with 10 μM 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoyl-benzo(f)quinoxaline-2,3-dione (NBQX) or 10 μM 2,3-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX).

After incubation, slices were mounted in a recording chamber on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope equipped with a ×40 water-immersion objective, infrared videomicroscopy, and gradient contrast optics (Dodt et al. 2002). A mercury lamp and GFP filter set were used to identify GFP expressing neurons. Whole cell recordings were made at 33–34°C using 2–4 MΩ electrodes filled with an intracellular solution composed of (in mM) 113 K-gluconate, 9 HEPES, 4.5 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 14 Tris2-phosphocreatine, 4 Na2-ATP, 0.3 tris-GTP; osmolality was brought to ∼290 mOsm with sucrose, pH adjusted to 7.25 with KOH. To improve inhibitory postsynaptic current (IPSC) detection, ECl was increased in some experiments to −55 mV by adding 6.6 mM KCl to the intracellular solution in place of an equal amount of K-gluconate. In one experiment (Fig. 8), ECl was decreased to −84 mV by lowering MgCl2 to 2.5 mM and adding 2.0 mM MgSO4. All data are corrected for a 13 mV junction potential.

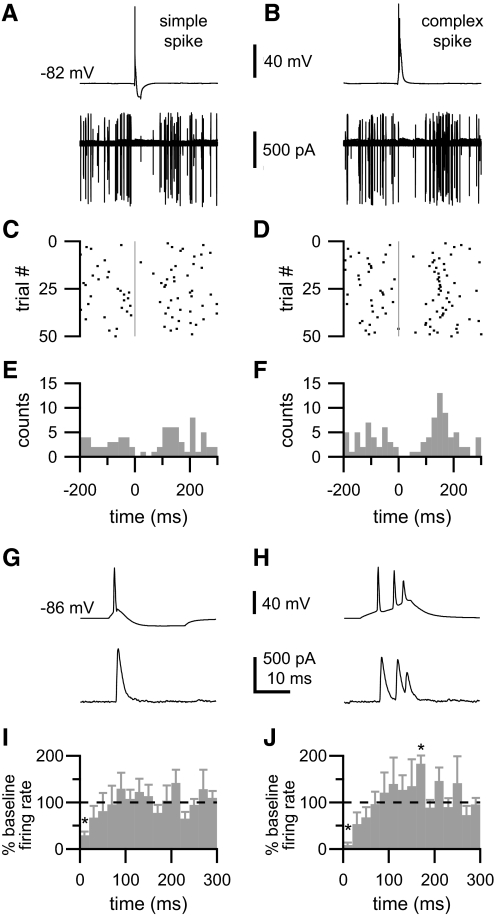

Fig. 8.

Cartwheel cell-evoked inhibitory PSPs (IPSPs) inhibit fusiform cell spontaneous firing. In a recording from a synaptically coupled cartwheel-fusiform cell pair, whole cell current injection was used to alternately elicit simple (A, top) and complex spikes (B, top) in a current-clamped cartwheel cell. Simultaneously, the firing rate of a postsynaptic, spontaneously active fusiform cell was monitored through cell-attached recording (A and B, bottom). A and B, top traces show typical, single trials; bottom traces: overlaid results from 50 trials. Simple spikes were elicited by brief, depolarizing current injections followed immediately by hyperpolarizing current injections. C and D: raster plots show pauses in fusiform cell firing subsequent to the onset (gray vertical lines) of presynaptic simple, C, or complex spikes, D. The cumulative effect of these pauses is apparent in histograms (E and F) measuring the number of fusiform action potentials per 20 ms bin from 50 trials. Note in F the tendency of the fusiform cell to fire 140–160 ms following the presynaptic complex spike. Time scale in E applies to A and C; scale in F to B and D. Data were aligned such that 0 ms indicates the peak of the presynaptic simple spike or peak of the first spike of the complex spike. G and H: rupturing the cell-attached patch permitted whole cell recordings of the IPSCs evoked in the fusiform cell (bottom) by simple and complex spikes (top). Fusiform cell was voltage-clamped at −73 mV. I and J: mean changes in fusiform cell spontaneous firing rate induced by simple, I, and complex spikes, J (n = 5; presynaptic spikes occurred at time = 0 ms; 20 ms bins). Asterisks denote significant changes from baseline firing rate (P < 0.05, t-test). Significant changes were also observed at approximately the same time ranges when bin size was decreased to 10 ms or increased to 25 ms (data not shown).

Data were sampled at 20–50 kHz and low-pass filtered at 3–10 kHz using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier, Digidata 1322A digitizer, and Clampex 9 software. Series resistance, <20 MΩ, was compensated by 80% in voltage-clamp recordings. In current-clamp recordings, pipette capacitance was neutralized and bridge balance maintained. Paired recordings were made from the somata of neighboring cells present in the same focal plane to maximize exposure of these cells to the same set of parallel fibers. Parallel fibers were stimulated with ACSF-filled electrodes made from theta-glass capillaries pulled to 2–4 μm tips or with bipolar tungsten electrodes with a 115 μm distance between termini (FHC). Both types of stimulating electrodes were driven by a Biphasic Stimulus Isolator (Dagan, Minneapolis, MN), which allowed the stimulus amplitude to be controlled through an analog signal from the Digidata.

Chemicals

4-Aminopyridine, DNQX, NBQX, and SR95531 were from Ascent Scientific. All others were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Data analysis

Most data analyses were performed with custom algorithms implemented in IgorPro (Wavemetrics). In the minimal stimulation experiment, paired pulse facilitation was used to increase the release probability of parallel fiber synapses, and therefore analyses were confined to excitatory PSCs (EPSCs) evoked by the second of the paired stimuli. An EPSC was considered to have occurred in response to the second stimulus if the peak amplitude of the current record within 5 ms of the onset of the stimulus artifact was more than three times the SD of the baseline. Event detection of spontaneous and miniature EPSCs and spontaneous IPSCs was conducted using the template-based fitting algorithm (Clements and Bekkers 1997) implemented in AxoGraph X (Axograph Scientific). Cross-interval correlation analyses were conducted according to Perkel et al. (1967). For each recording, the latency to the peak of each event from the beginning of the recording was determined with template-based event detection. Then for every event in cell 1, the lag to the nearest event before or after it in cell 2 was determined, and these lag times were binned to generate cross-interval histograms. Because recordings from cells 1 and 2 contained different numbers of events distributed differently in time, the results of comparing cell 1 versus cell 2 and cell 2 versus cell 1 were not equivalent. Cross-interval analysis therefore requires that the analysis be repeated with the two recordings swapped so as to find the lag from each event in cell 2 to the nearest event in cell 1, generating a second cross-interval histogram for each pair (Perkel et al. 1967). Events were defined as synchronous if they occurred within a lag of ±1 ms of each other. A certain fraction of events were synchronous due to random coincidence rather than a common presynaptic input. This fraction is directly proportional to the mean frequency of events in the other cell of the pair (Perkel et al. 1967). Thus for a cross-interval histogram where event counts have been normalized to the total number of events (i.e., events per bin/total events), the expected level of randomly coincident events is equal to the product of the bin width and the mean frequency of events in the other cell of the pair. For example, if 100 events were detected in cell 2 during a 1-s recording, the mean frequency of events in cell 2 would be 100 Hz, and 1-ms bins in the cross-interval analysis comparing events in cell 1 to cell 2 would be expected to have a 0.1% amplitude based on random synchrony. To quantify the percentage of synchronous events, we measured the fraction of events with lags between −1 and +1 ms and corrected this for the fraction of events expected to randomly coincide within a 2 ms time window. This was done for each of the two cross-interval analyses conducted per pair, and the resulting numbers were averaged to obtain a measure of the overall synchrony of events in each pair. Recordings of spontaneous EPSCs and IPSCs used for correlation analysis were ≥10 min long to ensure that correlations were drawn from a large pool of events.

Cell-attached recordings used to monitor action potentials were made in voltage-clamp mode with the holding potential adjusted to maintain the injected current near 0 pA to minimize the influence of the recording electrode on membrane potential (Perkins 2006). Action potentials recorded in cell-attached patches were detected using a threshold-crossing algorithm written in IgorPro. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was determined with t-test or one-way ANOVAs as appropriate. Errors correspond to SD except where noted.

RESULTS

Feedforward inhibition presupposes that single afferent inputs contact both an inhibitory interneuron and the postsynaptic target of the interneuron. In the DCN, this means that a single parallel fiber would synapse onto a cartwheel cell and its postsynaptic partners: principal (fusiform) cells or other cartwheel cells. To determine if this is indeed the case, we developed electrophysiological protocols to assess the connectivity between individual components of this circuit.

Minimal stimulation of parallel fibers

To assess whether individual parallel fibers are likely to synapse onto neighboring DCN neurons, we recorded from pairs of cartwheel cells, pairs of fusiform cells, and cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs. Slices were cut in the coronal plane, approximately parallel to the plane through which parallel fibers extend (Blackstad et al. 1984) to maximize the preservation of parallel fibers and their synapses. Pairs comprised of one or two cartwheel cells were tested to determine synaptic connectivity within the pair, and then 0.5 μm strychnine and 20 μm SR95531 were added to the bath to block inhibitory synaptic transmission. Using a fine theta-glass stimulus electrode inserted into the molecular layer, single parallel fibers were brought to action potential threshold with a “minimal stimulation” protocol. If the parallel fiber activated by a just-threshold stimulus synapsed onto both cells of the pair, then EPSCs should be detected in both cells simultaneously. Because parallel fibers may have a low release probability when extracellularly stimulated, which could result in synaptic failures (Dittman et al. 2000; but see Isope and Barbour 2002 for release probability of unitary connections), we increased the extracellular Ca2+ concentration of the ACSF used in this experiment to 4 mM and potentiated synapses through paired-pulse facilitation.

Two stimuli were delivered at 50 Hz every 10 s, and the stimulus amplitude was gradually increased until EPSCs were reliably detected in response to the second of the paired stimuli in one or both of the cells being recorded from (Fig. 1, A and B). For a given pair of neurons, the peak amplitudes of EPSCs elicited by the minimal stimulus tended to fall into a narrow range, and further increases in stimulus strength produced jumps in EPSC amplitude (Fig. 1, C and D), suggesting that we were able to detect the activation of individual parallel fibers. Across cells, the peak amplitudes of EPSCs evoked by the minimal stimuli averaged −54 ± 25 (SD) pA (range: −26 to −125 pA) in cartwheel cells and −33 ± 11 pA (range: −18 to −65 pA) in fusiform cells. In every pair examined, regardless of the identity of the neurons or their synaptic connectivity with one another, the minimal stimulus reliably evoked EPSCs in one cell but not the other. Larger stimuli, however, evoked EPSCs in the other cell of the pair, indicating that the second cell received input from parallel fibers passing through the stimulus site, just not from the parallel fiber activated by the minimal stimulus. It is therefore unlikely that parallel fibers synapsing onto the first cell of the pair were severed or otherwise topologically constrained before reaching the second cell.

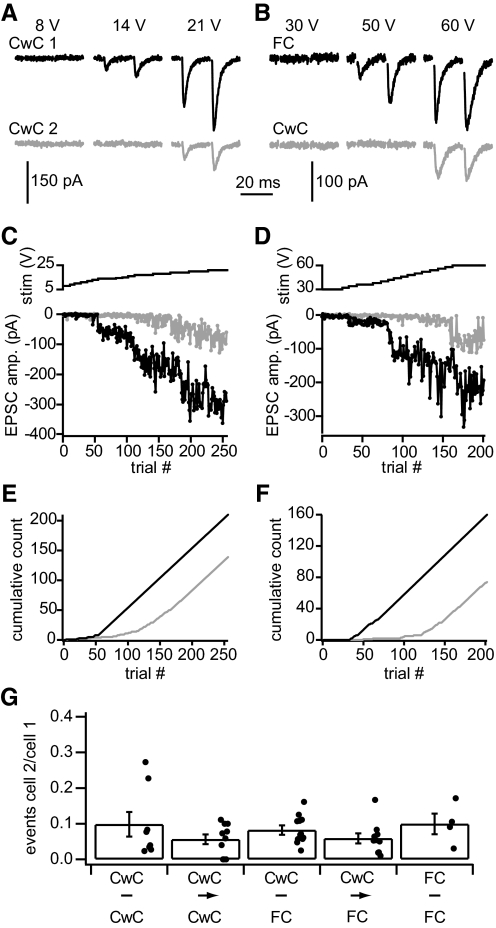

Fig. 1.

Individual parallel fibers activated by minimal stimulation synapse onto only 1 cell of a pair. A: in a recording from a pair of cartwheel cells that was not synaptically coupled, the minimal stimulus amplitude to reliably evoke excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) was 14 V. Stimuli at this amplitude evoked EPSCs in cartwheel cell 1 but not cartwheel cell 2, indicating that the activated parallel fiber only synapsed onto cartwheel cell 1. Larger stimuli activated additional parallel fibers and evoked EPSCs in both cells of the pair. B: similar to A but showing data from a synaptically coupled cartwheel-fusiform cell pair. The minimal stimulus (50 V) evoked EPSCs in the fusiform cell but not the cartwheel cell. C and D: as stimulus amplitudes were increased across trials, EPSCs were reliably detected in one cell of each pair (black data) before they were detected in the other (gray data). For each cell, EPSC amplitudes tended to cluster at certain levels consistent with stimuli of a given voltage range activating a constant number of parallel fibers. E and F: cumulative plots tracking when stimuli succeeded in evoking EPSCs. Data in C and E are from the pair shown in A; D and F from the pair in B. G: across the pairs tested, minimal stimuli reliably evoked EPSCs in 1 cell of each pair (lower threshold cell) while rarely evoking EPSCs in the other cell (higher threshold cell). The ratio of the number of EPSCs detected in the higher threshold cell versus the lower threshold cell prior to the reliable detection of EPSCs in the higher threshold cell quantifies this difference (see text for details). Five types of pairs were examined: pairs of cartwheel cells that were (CwC→CwC, n = 6 pairs, 10 stimulus sites) or were not (CwC-CwC, n = 6 pairs, 8 stimulus sites) synaptically coupled, cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs that were (CwC→FC, n = 6 pairs, 10 stimulus sites) or were not (CwC-FC, n = 6 pairs, 10 stimulus sites) synaptically coupled, and pairs of fusiform cells (FC-FC, n = 2 pairs, 4 stimulus sites). No group of pairs was significantly different from another (P > 0.05, 1-way ANOVA). Error bars show SE.

EPSC records were quantified by establishing whether the second of each paired stimuli failed or succeeded in evoking an EPSC. Cumulative distributions tracking successful events show clear differences in when EPSCs were first evoked in each cell of a pair (Fig. 1, E and F). To summarize results across pairs, we identified thresholds for evoking EPSCs by finding the lowest trial number where EPSCs were evoked in three consecutive trials for each cell of each pair. From the region between the EPSC threshold of the first cell and that of the second, the ratio of the number of detected EPSCs in the higher threshold cell, cell 2, versus the lower threshold cell, cell 1, was taken. This ratio provides a measure of how distinct the lowest stimulation threshold inputs to each cell were from one another. Pairs were grouped according to cell identity and cartwheel cell synaptic connectivity, which will be discussed later. For each group of pairs, there was an average of more than ten events in the lower EPSC threshold cell for every event in the higher EPSC threshold cell (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that individual parallel fibers are unlikely to synapse onto two neighboring cells.

Spontaneous EPSCs recorded from pairs of neurons

While the minimal stimulation experiment permitted a controlled examination of the synaptic connectivity of an individual parallel fiber, it was limited by the fact that only one parallel fiber could be probed for each recorded pair of neurons. To more broadly sample connectivity of parallel fibers and obtain an estimate of the overlap in parallel fiber input to neighboring cells, we looked for correlations in the occurrence of spontaneous EPSCs (sEPSCs) within pairs of neurons. Parallel fibers provide the sole source of glutamatergic input to cartwheel cells and, along with auditory nerve afferents and possibly T stellate cells, are one of two or three sources of excitatory input to fusiform cells (Mugnaini 1985; Oertel et al. 1990; Rubio and Juiz 2004; Rubio and Wenthold 1997, 1999; Ryugo and May 1993; Smith and Rhode 1985). Recordings were made from 37 pairs in the presence of blockers of inhibitory synaptic transmission and 30 μM 4-aminopyridine, a potassium channel blocker we used to promote spontaneous firing of parallel fibers. In these recordings, we detected rare instances where sEPSCs occurred synchronously (i.e., within 1 ms of one another) in both cells of some pairs (Fig. 2A, *) while in other pairs such instances did not occur (B).

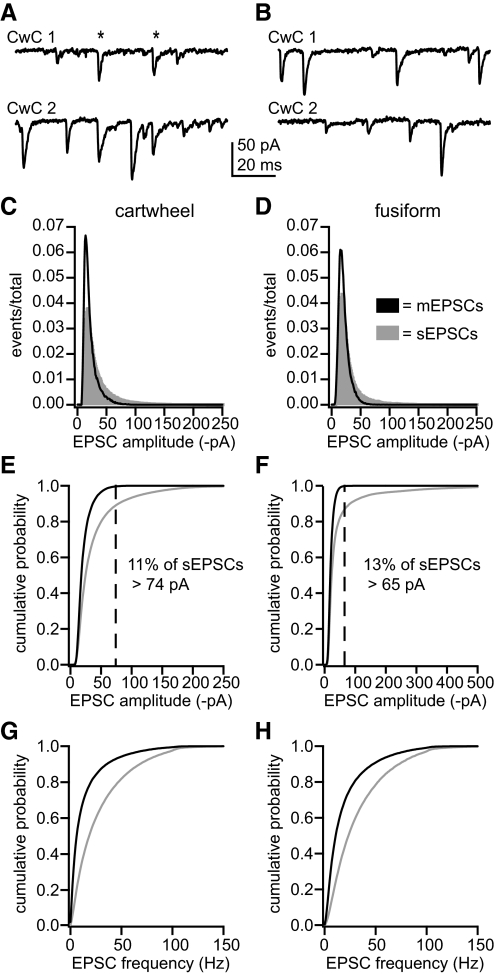

Fig. 2.

Comparison of miniature and spontaneous EPSC (mEPSC and sEPSC) properties. Synchronous EPSCs were occasionally detected in the pair of reciprocally connected cartwheel cells in A (*) but not the pair of reciprocally connected cartwheel cells in B. In cartwheel cells, C, and fusiform cells, D, distributions of sEPSC amplitudes ( ) were skewed toward larger events than distributions of mEPSC amplitudes (■). In cartwheel cells, mean EPSC amplitudes were 22.4 ± 2.8, mEPSCs, and 39.5 ± 21.0, sEPSCs. In fusiform cells, mean EPSC amplitudes were 21.6 ± 4.0, mEPSCs, and 46.3 ± 51.0, sEPSCs. E and F: cumulative distributions of the amplitude data shown in C and D, respectively. More than 99% of mEPSCs were smaller than the amplitude cutoffs (dashed lines), which were established to distinguish between sEPSCs that might have resulted from miniature release events and those that were probably the product of action potential-evoked release. In cartwheel cells, 11% of sEPSCs were larger than the 74 pA cutoff, and, in fusiform cells, 13% were larger than the 65 pA cutoff. G and H: cumulative distributions of instantaneous EPSC frequencies. Mean sEPSC frequencies were significantly higher than mean mEPSC frequencies in cartwheel cells, G, and fusiform cells, H, (t-test, P < 0.05). Cartwheel cells: sEPSC frequency = 29 ± 9 Hz, mEPSC frequency = 14 ± 5 Hz. Fusiform cells: sEPSC frequency = 33 ± 9 Hz, mEPSC frequency = 20 ± 3 Hz. All distributions represent averages of distributions across multiple cells for each group. Cartwheel cells: n = 8, mEPSC group; 52, sEPSC group. Fusiform cells: n = 6, mEPSC group; 22, sEPSC group.

) were skewed toward larger events than distributions of mEPSC amplitudes (■). In cartwheel cells, mean EPSC amplitudes were 22.4 ± 2.8, mEPSCs, and 39.5 ± 21.0, sEPSCs. In fusiform cells, mean EPSC amplitudes were 21.6 ± 4.0, mEPSCs, and 46.3 ± 51.0, sEPSCs. E and F: cumulative distributions of the amplitude data shown in C and D, respectively. More than 99% of mEPSCs were smaller than the amplitude cutoffs (dashed lines), which were established to distinguish between sEPSCs that might have resulted from miniature release events and those that were probably the product of action potential-evoked release. In cartwheel cells, 11% of sEPSCs were larger than the 74 pA cutoff, and, in fusiform cells, 13% were larger than the 65 pA cutoff. G and H: cumulative distributions of instantaneous EPSC frequencies. Mean sEPSC frequencies were significantly higher than mean mEPSC frequencies in cartwheel cells, G, and fusiform cells, H, (t-test, P < 0.05). Cartwheel cells: sEPSC frequency = 29 ± 9 Hz, mEPSC frequency = 14 ± 5 Hz. Fusiform cells: sEPSC frequency = 33 ± 9 Hz, mEPSC frequency = 20 ± 3 Hz. All distributions represent averages of distributions across multiple cells for each group. Cartwheel cells: n = 8, mEPSC group; 52, sEPSC group. Fusiform cells: n = 6, mEPSC group; 22, sEPSC group.

Interpretation of these data was complicated by the fact that sEPSCs are elicited by both miniature and action potential-evoked release events. Because they randomly occur at individual boutons, miniature release events decrease the apparent correlation of sEPSCs in paired recordings. We therefore developed an amplitude cutoff criterion to exclude miniature EPSCs (mEPSCs) from the data set. In the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin to block action potentials, mEPSCs were recorded from cartwheel and fusiform cells, detected with a template-based event detection algorithm (Clements and Bekkers 1997), and their amplitudes and frequencies characterized. The same analysis was then applied to the sEPSC data set. In both cartwheel and fusiform cells, the sEPSC amplitude distributions skewed toward larger events than the mEPSC distributions (Fig. 2, C and D). Based on cumulative probability distributions prepared from the amplitude data for each cell in the mEPSC data set, amplitude cutoffs were established as the mean 99%-amplitude plus twice the SD of the mean. For cartwheel cells, this meant that sEPSCs >74 pA were most likely action potential-evoked. For fusiform cells, the mEPSC cutoff was 65 pA. Comparison of the overall cumulative probability distributions of mEPSC and sEPSC amplitudes shows that 11% of sEPSCs recorded in cartwheel cells were larger than the cutoff (Fig. 2E), and 13% were larger than the cutoff in fusiform cells (F). Finally, the frequency distributions of the mEPSC and sEPSC data sets in cartwheel and fusiform cells demonstrated, as expected, that the frequency of events in the sEPSC data set was higher than that in the mEPSC data set (Fig. 2, G and H).

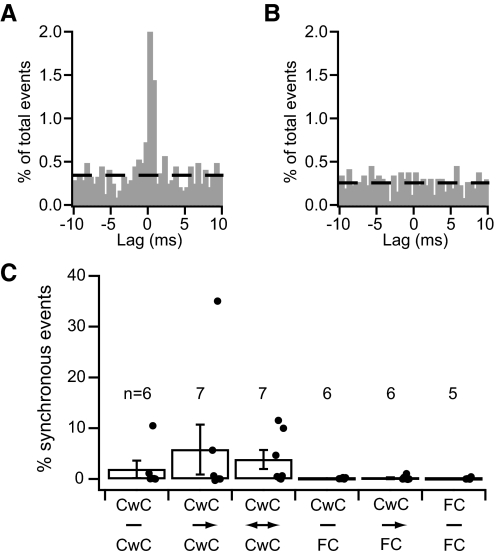

With amplitude cutoffs in place to exclude potential mEPSCs from the data, we returned to comparing the sEPSC recordings from pairs of neurons. To do this, we used cross-interval analysis, a correlation procedure in which the time interval, or lag, from each event recorded from one cell to the nearest event before or after it in the other cell is found (Perkel et al. 1967). Together these intervals make up a cross-interval histogram (see methods for details). For some pairs, cross-interval histograms revealed a peak near zero lag, indicating that at least one parallel fiber synapsed onto both cells of the pair (Fig. 3A). In other pairs, no peak was apparent, indicating little or no common parallel fiber input between the two cells (Fig. 3B). To summarize the EPSC correlation across pairs, we measured the percentage of lag times in each cross-interval analysis that fell within ±1 ms of zero lag. These results show that synchronous sEPSCs were relatively rare across the cartwheel and fusiform cell pair combinations tested (Fig. 3C). We were concerned that applying the amplitude cutoff criteria to both cells of each pair might be too stringent, as this requires that spontaneous action potential-evoked EPSCs in both cells be relatively large to be counted in the correlation analysis. Thus we performed the cross-interval analysis again, this time comparing EPSCs larger than the amplitude cutoff in one cell of a pair with EPSCs of any size in the other cell, then repeated this, swapping the criteria for each cell. Even with this approach, only a few pairs exhibited synchrony levels exceeding 20% of sEPSCs (Supplemental Fig. S1)1.

Fig. 3.

sEPSCs were rarely correlated in paired recordings. A and B: cross-interval histograms analyzing the relative timing of sEPSCs from the same pairs shown in Fig. 2, A and B, respectively. The peak near 0 lag in A indicates that a portion of sEPSCs detected in that pair occurred simultaneously. Dashed lines, bin heights expected from randomly coincident events. C: the percentage of sEPSCs that occurred synchronously in pairs of various compositions and synaptic connectivities averaged <6% for each group. Analyses only compared events that were unlikely to be mEPSCs (see text). No group of pairs was significantly different from another (P > 0.05, 1-way ANOVA) or from 0 (P > 0.05, t-test). Error bars show SE.

In pairs where one or both neurons were fusiform cells, another concern was that sEPSCs generated by input to fusiform cells from auditory nerve afferents or T stellate cells could have resulted in a spurious decrease or increase in sEPSC synchrony levels. Little is known about the synaptic connectivity patterns of these inputs to neighboring fusiform cells, and there was no clear way for us to identify the source of a given sEPSC. The results of the cross-interval analysis, however, are consistent with those from the minimal stimulation experiment which selectively targeted parallel fibers. Also, this concern does not apply to cartwheel-cartwheel cell pairs, and there are no data indicating that the distribution of synapses from individual parallel fibers onto pairs of neighboring cartwheel cells differs significantly from the distribution onto cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs or fusiform-fusiform cell pairs. Together, these results suggest that while there is some common parallel fiber input to pairs of neighboring neurons, the majority of inputs to each cell are not shared.

One caveat to the minimal stimulation and EPSC correlation experiments (Figs. 1–3) is that dendritic filtering might have prevented the detection of small EPSCs generated by parallel fiber synapses onto the distal dendrites of cartwheel and fusiform cells, which are known to possess complex dendritic arbors with numerous branches (Golding and Oertel 1997; Manis et al. 1994; Roberts et al. 2008; Zhang and Oertel 1993, 1994). It is therefore possible that the data underestimate the number of common parallel fiber inputs to pairs of neighboring neurons, e.g., missing parallel fibers synapsing onto the proximal dendrites of one neuron and the distal dendrites of another. The focus here, however, was to examine how parallel fibers shape the output of local circuits in the molecular layer, and EPSPs that attenuate before reaching the soma are unlikely to significantly influence cartwheel or fusiform cell firing. Thus the preceding experiments show that there is little functionally relevant overlap in parallel fiber input to neighboring neurons.

Effects of parallel fiber-evoked EPSPs on cartwheel and fusiform cell excitability

Mossy inputs to granule cells in the cochlear nuclei carry information from diverse modalities (Oertel and Young 2004). Another approach to revealing feedforward inhibition is to ask how effective single fibers (presumably representing a narrow range of sensory information) are in driving cartwheel cells versus fusiform cells. If single inputs are weak, then many afferents would be required to act in concert to drive cartwheel cells. In that case, inhibition of cartwheel cell targets could not likely result from a single sensory modality. To explore this, we tested the effectiveness of inputs to drive spikes in quiescent cartwheel and fusiform cells (cells held below threshold) and to increase spike rate in cartwheel and fusiform cells with ongoing, background firing. Both approaches are important because in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that while the majority of cartwheel and fusiform cells fire spontaneously, a portion of cells of both types are quiescent in the absence of external stimuli (Davis and Young 1997; Davis et al. 1996; Golding and Oertel 1997; Kim and Trussell 2007; Manis 1990; Manis et al. 1994; Parham and Kim 1995; Portfors and Roberts 2007; Waller and Godfrey 1994; Wei et al. 2010; Young et al. 1995; Zhang and Oertel 1993, 1994). For these experiments, our standard ACSF was replaced with one containing lower Ca2+ and K+ concentrations to better approximate in vivo ion concentrations (see methods) and blockers of inhibitory synaptic transmission were included in the bath.

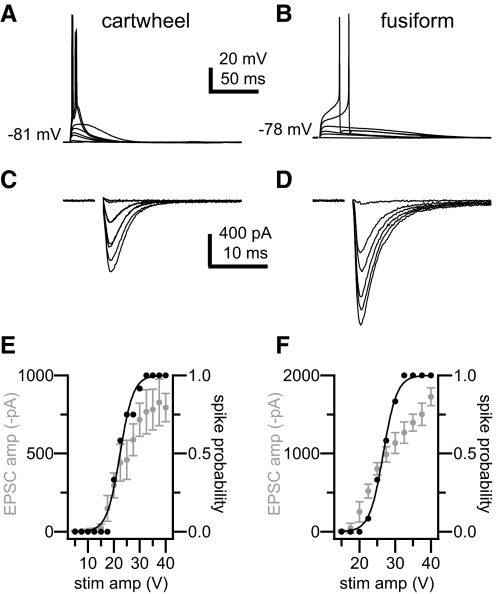

In the first approach, whole cell recordings were made in current-clamp mode. Small bias currents were injected to maintain membrane potentials at levels typical of quiescent cartwheel and fusiform cells (Kim and Trussell 2007; unpublished observations), i.e., levels that are only slightly negative to those where spontaneous firing occurred. These bias currents also served to standardize the resting membrane potential across cells within each cell type. In the cartwheel cell group, one of five cells was spontaneously firing on break-in, and cells were held at −82.6 ± 1.3 mV with an average current injection of −29 ± 69 pA (range: −100 to +75 pA). In the fusiform cell group, four of five cells were spontaneously firing on break-in, and an average current injection of −150 ± 71 pA (range: −50 to −250 pA) held these cells at −76.8 ± 3.0 mV. A bipolar stimulating electrode placed in the molecular layer delivered single stimuli of varying amplitudes every 10 s until a range of amplitudes was identified that evoked no EPSP on the low end and an EPSP large enough to consistently elicit one or more action potentials on the high end (Fig. 4, A and B). Responses to stimuli across this range were recorded several times, and the probability that stimuli of a given strength would produce one or more action potentials was calculated (Fig. 4, E and F, black data). The relationship between spike probability and stimulus amplitude was sigmoidal, allowing us to find the stimulus strength that produced an action potential ∼50% of the time. Based on instances where stimuli at this 50% level evoked EPSPs but not action potentials, we calculated that an EPSP of 10.9 ± 2.4 mV in cartwheel cells and 10.1 ± 2.8 mV in fusiform cells elicited action potentials with a 50% probability. For each cell, after current-clamp recordings were completed, the stimulus protocol was repeated in voltage-clamp mode to measure the synaptic current evoked at each stimulus strength (Fig. 4, C and D). The relationship between EPSC amplitudes and stimulus strength was similar to that for spike probabilities (Fig. 4, E and F, gray data). Stimulus amplitudes that evoked action potentials with ∼50% probability yielded EPSCs that were 430 ± 180 pA in cartwheel cells (range: 210–700 pA) and 540 ± 300 pA in fusiform cells (range: 210–990 pA). These currents are significantly larger than the EPSCs elicited by stimulation of individual parallel fibers in the minimal stimulation experiment (P < 0.01 for cartwheel cells, P < 0.05 for fusiform cells). Indeed they indicate that synchronous activation of 8 and 16 parallel fibers, respectively, are needed to drive cartwheel and fusiform cells to spike from a quiescent state.

Fig. 4.

Parallel fiber-evoked excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) elicit action potentials in a cartwheel cell (left) and a fusiform cell (right) at rest. A and B: stimuli over a range of amplitudes delivered to the molecular layer elicited no response, EPSPs of various amplitudes, or action potentials in whole cell current-clamp recordings of a cartwheel cell and a fusiform cell. C and D: voltage-clamp recordings from the same cells demonstrate the currents elicited by stimuli over the tested range of amplitudes. E: summary data for the cartwheel cell in A and C. F: summary data for the fusiform cell in B and D. As stimulus amplitudes increased, the probability of evoking ≥1 action potentials (black data) in current-clamp recordings grew sigmoidally (E, cartwheel cell, x-half = 22.4 ± 0.4 V, r2 = 0.984; F, fusiform cell, × x-half = 26.7 ± 0.1 V, r2 = 0.998). Amplitudes of the underlying EPSCs exhibited corresponding increases (gray data). Error bars show SD.

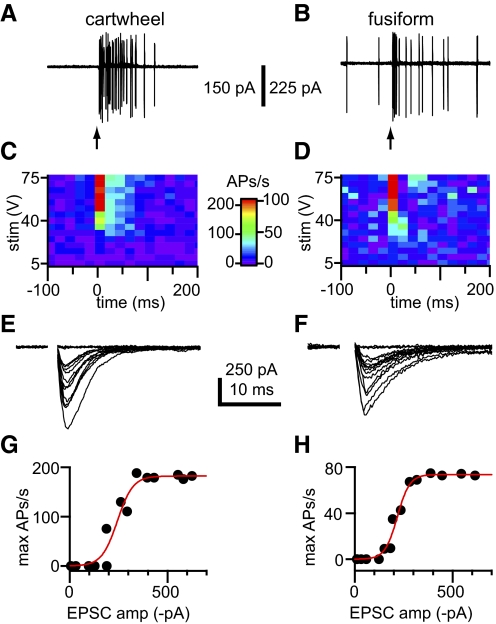

Data from in vivo and in vitro recordings indicate that spontaneously active fusiform cells fire at rates of ∼10–90 Hz, while spontaneously active cartwheel cells fire at rates of ∼10–30 Hz (Davis and Young 1997; Davis et al. 1996; Golding and Oertel 1997; Kim and Trussell 2007; Manis 1990; Manis et al. 1994; Parham and Kim 1995; Portfors and Roberts 2007; Waller and Godfrey 1994; Wei et al. 2010; Young et al. 1995; Zhang and Oertel 1993, 1994). Therefore in the second approach, we used cell-attached recordings to examine the capacity of parallel fiber EPSPs to elicit action potentials in cells that were spontaneously firing. Single stimuli ranging from 5 to 75 V were delivered every 10 s to the molecular layer via a bipolar electrode. Spontaneous and EPSP-evoked action potentials were detected in cell-attached voltage-clamp recordings as sharp spikes, proportional to the first derivative of the underlying action potentials (Perkins 2006). Stimuli on the larger end of the tested range elicited action potentials with a short latency (Fig. 5, A–D). Cartwheel cells often responded to large stimuli by firing bursts of action potentials with inter-spike intervals consistent with those of complex spikes, while fusiform cells often responded by firing trains of two or more action potentials. Once the response to the full range of stimuli was tested in repeated trials, the cell-attached patch was ruptured and the EPSCs evoked by each stimulus strength were assessed with whole cell voltage-clamp recordings (Fig. 5, E and F). This allowed us to correlate the peak changes in firing rate brought about by parallel fiber stimuli with the peak amplitudes of the underlying EPSCs (Fig. 5, G and H). The relationship between these parameters was sigmoidal, and the half-point of sigmoidal fits to the data provided an estimate of the EPSC amplitude required to bring about a 50% of maximal increase in firing rate. For cartwheel cells, this amplitude was 245 ± 113 pA (range: 110–415 pA); for fusiform cells it was 475 ± 327 pA (range: 106–826 pA). Both of these mean EPSC amplitudes were significantly greater than the EPSC amplitudes elicited by minimal stimuli in the minimal stimulation experiment (t-test, P < 0.05). We also determined the amplitudes of the EPSCs elicited by the smallest stimuli that reliably increased firing above baseline rates (cartwheel cells: 162 ± 48 pA, range: 110–222 pA; fusiform cells: 325 ± 199 pA, range: 79–531 pA). These EPSCs were also significantly greater than the EPSCs evoked by minimal stimuli (t-test, P < 0.05). Again using the amplitude of minimal EPSCs presented in the preceding text, these results indicate that coordinated input from 3 and 10 parallel fibers is required to increase firing rates above background in cartwheel and fusiform cells, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Parallel fiber-evoked EPSPs elicit extra action potentials in a spontaneously firing cartwheel cell (left) and a spontaneously firing fusiform cell (right). A and B: in cell-attached recordings, stimuli ranging from 0 to 75 V were delivered to the molecular layer. Larger stimuli evoked the firing of additional action potentials, occasionally eliciting complex spikes in cartwheel cells, as in A, and bursts of ≥2 spikes in fusiform cells as in B. Arrows indicate when stimuli occurred. C and D: summary analyses showing changes in action potential firing rates elicited by stimuli from the tested range of amplitudes for the same cells as in A and B. Data represent the mean changes across 10 trials (cartwheel cell) and 15 trials (fusiform cell). Time axes in C and D also apply to A and B. E and F: after break-in to whole cell mode, the EPSCs evoked by the tested range of stimulus amplitudes were measured. G: summary data for the cartwheel cell in A, C, and E. H: summary data for the fusiform cell in B, D, and F. There was a sigmoidal relationship between the average, peak change in firing rate evoked by each stimulus amplitude and the corresponding mean amplitude of the EPSCs evoked by these stimuli (G, cartwheel cell, x-half = 248 ± 11 pA, r2 = 0.950; H, fusiform cell, x-half = 219 ± 5 pA, r2 = 0.984). A, B, E, and F are overlays of 15 sweeps.

Distribution of inhibitory synapses

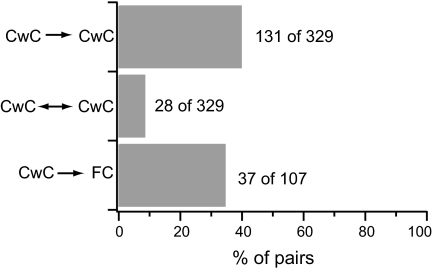

We next asked if contacts made by inhibitory interneurons on principal cells or other inhibitory interneurons are as “sparse” as the excitatory contacts they receive. There are two main types of inhibitory interneurons in the DCN molecular layer, cartwheel and stellate cells. For cartwheel cells, we have a direct measure of synaptic connectivity using whole cell recordings made from pairs of neighboring neurons (Roberts et al. 2008). Every time a recording was obtained from a pair of cartwheel cells or a cartwheel–fusiform cell pair, the putative presynaptic cartwheel cell was held in current clamp, and a complex spike was evoked with a current step; IPSCs triggered in the other cell indicated a synaptic contact between the pair. We routinely tested this protocol in both directions to determine if either cell was presynaptic. From this experiment, we found that in 131 of 329 (39.8%) cartwheel cell pairs, one cell of the pair was synaptically coupled to the other, while another 28 of 329 (8.5%) cartwheel cell pairs were reciprocally coupled (Fig. 6). Taking the 329 pairs as a sample of 658 potential connections, these data indicate a probability for a cartwheel cell to synapse onto another nearby cartwheel of (131 + 28 × 2)/658 or 28.4%. This accurately predicts (0.284̂2 = 0.081) the observed frequency of reciprocal connections (0.085).

Fig. 6.

Cartwheel cells are likely to synapse onto neighboring cartwheel and fusiform cells. In recordings from pairs of cartwheel cells, 1 cartwheel cell made a functional synapse onto the other in 39.8% of pairs (CwC→CwC). Another 8.5% of pairs were reciprocally coupled, meaning that each cartwheel cell in the pair synapsed onto the other (CwC↔CwC); 34.6% of cartwheel cells synapsed onto fusiform cells in cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs (CwC→FC). Numbers to right of bars indicate incidence of coupled pairs among the number of pairs tested.

In cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs, the cartwheel cell synapsed onto the fusiform cell in 37 of 107 (34.6%) cases, which can be directly taken as the probability of a cartwheel cell synapsing onto a nearby fusiform cell (Fig. 6). Cartwheel cells possess local axons, and the mean soma-to-soma distance of the examined pairs of cartwheel cells was 17.3 ± 8.7 μm. For cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs, the mean distance between somata was 17.3 ± 6.9 μm. Cartwheel axons in mouse ramify over an area of roughly 100 μm (K. Bender and L. Trussell, unpublished observations). Thus it is likely that the synaptic connectivity rates for cartwheel cells and potential postsynaptic partners drops sharply as the distance between cells increases as was found in one recent study (Mancilla and Manis 2009). Nevertheless, these data indicate that it is very likely that cartwheel and fusiform cells within a local circuit receive a significant amount of common inhibitory input from other nearby cartwheel cells. The higher probability for cartwheel-fusiform than cartwheel-cartwheel synapses (35 vs. 28%) may simply reflect the larger size of fusiform cells (Zhang and Oertel 1993, 1994).

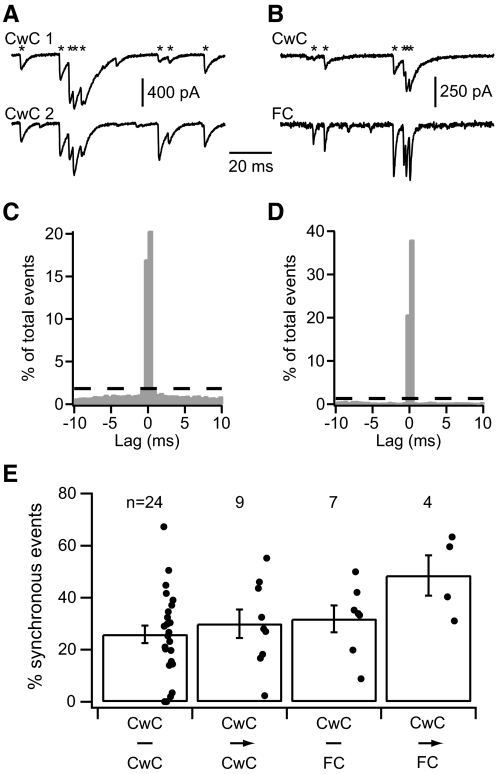

To more broadly investigate the degree of coupling among neighboring neurons, we recorded spontaneous IPSCs (sIPSCs) from cartwheel-cartwheel and cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs while blocking excitatory synaptic transmission. In nearly every pair examined, numerous sIPSCs were detected synchronously in both cells of the pair (Fig. 7, A and B). Often, synchronous sIPSCs occurred in bursts with interevent timings similar to the interspike intervals of complex spikes, suggesting that at least some of these sIPSCs were elicited by cartwheel cells that synapsed onto both cells of the pair. As we did previously for sEPSCs, the timings of sIPSCs recorded from one cell of a pair were compared with those from the other by detecting sIPSCs with a template-matching algorithm and correlating their timings with cross-interval analysis. For the example pairs shown in Fig. 7, the cross-interval histograms exhibit large peaks near zero lag time, indicating that a significant percentage of sIPSCs occurred synchronously (C and D).

Fig. 7.

Spontaneous IPSCs were frequently correlated in paired recordings. In a pair of synaptically coupled cartwheel cells, A, and a synaptically coupled cartwheel-fusiform cell pair, B, spontaneous inhibitory PSCs (sIPSCs) often occurred at the same time in both cells of each pair (asterisks). Many of these synchronous sIPSCs occurred in bursts, presumably due to the firing of complex spikes in a common presynaptic cartwheel cell. C and D: cross-interval histograms with large peaks near 0 lag indicate that a large portion of the sIPSCs detected in 1 cell of the pairs from A and B were correlated in time with sIPSCs detected in the other cell of each pair. Dashed lines indicate the bin counts expected from randomly coincident events. E: synchronous sIPSCs were commonly detected in recordings from pairs of cartwheel cells and cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs, whether or not they were synaptically coupled. The mean for each pair group was significantly greater than 0 (t-test, P < 0.05). N, number of pairs in each group.

Across the populations of pairs tested, the average percentage of synchronous sIPSCs was 29.8%, with some pairs showing >50% synchronous sIPSCs (Fig. 7E). In 42 of the 44 pairs (95%), ≥1% of the IPSCs were synchronous, and 38 pairs (86%) exhibited a synchrony level exceeding 10%. These numbers indicate that even in the slice preparation, where some synaptic connections are presumably cut, most neighboring neurons share at least one common inhibitory input. Average synchrony levels were not significantly different for pairs of cartwheel cells versus cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs, nor were they affected by whether or not a cartwheel cell synapsed onto the other cell of the pair (1-way ANOVA, P > 0.05). Additionally, in two instances, we recorded from pairs of neighboring fusiform cells, i.e., fusiform-fusiform cell pairs, and observed synchrony levels similar to those found for the other pair types (data not shown). These results point to the possibility that the proximity of two cells within the local circuit has more influence on the commonality of their inhibitory input than does their identity or synaptic connectivity with one another. Importantly, the average percentages of synchronous sIPSCs are >10-fold higher than those earlier determined for sEPSCs (Fig. 3; P < 0.05 in t-test comparing sEPSC to sIPSC data within each pair group). Because of this, we thought it unlikely that the outcome of this experiment was much affected by contamination of the sIPSC data set with miniature IPSCs (which would only lead to an underestimate of correlated activity). Thus we did not characterize miniature IPSCs or devise a method for removing them from the data set. Even so, these data indicate that the inhibitory input to pairs of neighboring neurons is highly similar, suggesting that molecular layer inhibitory interneurons densely distribute their synaptic output to targets within their local circuits.

Cartwheel cells inhibit fusiform cell spontaneous firing

Having examined connectivity within this circuit and the efficacy of the afferent input, we next asked how effectively does the cartwheel cell inhibit its postsynaptic partners? We previously examined this question for cartwheel-cartwheel contacts and found that single cell-elicited IPSPs blocked the firing of complex spikes (Roberts et al. 2008). Here we tested the capacity of cartwheel cell-elicited IPSPs to modulate the firing rates of spontaneously active fusiform cells. Recordings were made from cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs, and, to maintain intrinsic activity, fusiform cells were monitored with cell-attached, voltage-clamp recordings. Cartwheel cells were current-clamped in whole cell mode, and brief depolarizing currents were injected to alternately elicit a simple spike or a complex spike every 15 s. In pairs that were synaptically coupled, both simple and complex spikes caused pauses in fusiform cell spontaneous firing (Fig. 8, A and B). To characterize these pauses, action potentials were identified with a threshold-crossing event detection algorithm. Raster plots of action potentials showed consistent pauses in spontaneous firing following stimulation of the presynaptic cartwheel cell (Fig. 8, C and D) as did histograms in which data from repeated trials were binned (E and F). For each pair, the synaptic connection between the cartwheel cell and fusiform cell was verified by rupturing the cell-attached patch on the fusiform cell and obtaining whole cell recordings of the IPSCs elicited by cartwheel cell simple and complex spikes (Fig. 8, G and H). In these whole cell recordings, fusiform cells were voltage-clamped between −68 and −73 mV. The mean amplitude of IPSCs elicited by simple spikes or the first spike of a complex spike was 333 ± 257 pA (range: 107–802 pA). Because the chloride reversal potential of the intracellular solution used for this experiment was modified to reflect the −84 mV ECl of fusiform cells (Kim and Trussell 2009), these IPSC amplitudes approximate, but somewhat underestimate, those experienced by fusiform cells while depolarized by spontaneous spiking during cell-attached recordings.

In five cartwheel-fusiform cell pairs, we were able to maintain fusiform cells stably for >30 min in cell-attached mode, have them survive rupture to whole cell mode, obtain stable whole cell recordings for several minutes more, and also confirm that the cells were in fact synaptically coupled, as shown by the presence of an evoked IPSC. The average spontaneous firing rate of the fusiform cells in these pairs was 8.4 ± 4.9 action potentials per second. Using the average firing rate of each pair as a baseline, we sorted action potentials into 20-ms bins, measured the relative change in firing rate brought about by cartwheel cell simple and complex spike-evoked IPSPs, and averaged these changes across the five pairs in the data set (Fig. 8, I and J). Both simple and complex spike-evoked IPSPs caused a significant reduction in spontaneous firing for 20 ms following the IPSP with a trend toward decreases in firing rate lasting another 20–40 ms. In addition, the decrease in firing rate during the first 20 ms was significantly greater for inhibition evoked by complex spikes (8.39 ± 5.29% of baseline) than it was for simple spikes (29.58 ± 8.2% of baseline; pairwise t-test, P = 0.026), suggesting that the burst of IPSPs elicited by a complex spike exerted a stronger inhibitory effect than the single IPSP elicited by a simple spike. The mean latency to the first fusiform cell spike following the onset of inhibition was 112 ± 67 ms for simple spike inhibition and 115 ± 55 ms for complex spike inhibition. Interestingly, presynaptic complex spikes also led to a significant increase in postsynaptic firing rate at 160–179 ms following the onset of the burst of IPSPs (Fig. 8J), suggesting that while complex spike-mediated inhibition does not prolong inhibition of spontaneous activity compared with a simple spike, it might enhance synchrony in the timing of the next action potential following inhibition. This effect is presumably due to postinhibitory rebound currents (e.g., Aizenman and Linden 1999). Together, these data indicate that inhibition from a single cartwheel cell is sufficient to modify the output of fusiform cells.

DISCUSSION

The distribution and strength of synaptic connections determines how local circuits process information. In the DCN, we found that individual parallel fibers were unlikely to synapse onto neighboring neurons, suggesting that neighboring neurons receive distinct subsets of sensory input. Individual parallel fibers were too weak to alter firing in cartwheel or fusiform cells, indicating that only temporally correlated input from multiple fibers drives significant changes in activity. By contrast, inhibitory interneuron connectivity was very high with individual cartwheel cells synapsing onto more than 1/4 of their near-neighbors. Moreover, synaptic input from single cartwheel cells significantly modified postsynaptic activity. We propose that the set of parallel fibers activated by a particular sensory stimulus determines the mode of inhibition a cartwheel cell provides to its postsynaptic partners. Thus cartwheel cells may alternate between feedforward inhibition, which limits the time window for synaptic integration, and lateral inhibition, which narrows the range of parallel fiber-distributed sensory information that increases circuit output.

Distribution of sensory information by parallel fibers

While previous studies characterized parallel fiber synapses onto spiny dendrites of cartwheel and fusiform cells, it remains unclear how the synapses of individual fibers are distributed among postsynaptic neurons (Mugnaini 1985; Mugnaini et al. 1980b; Osen et al. 1995; Smith and Rhode 1985). We propose that each parallel fiber has a low probability of synapsing onto any particular cell within a local circuit. Activating individual parallel fibers with minimal stimulation did not reveal any instances in 26 paired recordings with 42 stimulus sites where a parallel fiber elicited postsynaptic responses in two neighboring cells. In addition, the occurrence of synchronous spontaneous EPSCs in paired recordings was rare with <10% of sEPSCs detected in one cell of a pair occurring within 1 ms of a sEPSC in the other cell.

What might explain the sparseness of parallel fiber synapses? Because parallel fibers extend in relatively straight paths (Mugnaini et al. 1980b; Oertel and Wu 1989), there might be limited opportunities for dendritic arbors of potential postsynaptic partners to come close enough to a given parallel fiber to form a synapse (Stepanyants and Chklovskii 2005). For pairs of neighboring neurons, the probability of both receiving synapses from a given parallel fiber will be reduced if the dendritic arbors of these neurons extend at different angles from their parent somata or do not extend equally into the molecular layer. Alternatively, synapse number and interval may be limited in parallel fibers (Shepherd and Raastad 2003). In cerebellar cortex, quantitative analysis indicates that parallel fiber varicosities (synaptic boutons) are spaced an average of 5.2 μm apart (Shepherd et al. 2002). Even a parallel fiber passing in close proximity to a cerebellar Purkinje cell dendrite has only slightly better than a 50% chance of synapsing onto that dendrite (Harvey and Napper 1991). Similar measures for DCN parallel fibers have not been made. A third possibility is that parallel fibers make many synapses, but these are often functionally “silent,” as in cerebellum (Ekerot and Jorntell 2001; Isope and Barbour 2002).

Given the relative amplitude of EPSCs produced by single parallel fibers versus just-suprathreshold EPSCs, we estimate that activation of ∼8 and 16 parallel fibers are required to elicit spikes from rest in cartwheel and fusiform cells, respectively; closer to half those numbers are needed to increase ongoing firing (3 for cartwheel cells; 10 for fusiform cells). As in cerebellum (Barbour 1993), multiple parallel fibers must therefore provide temporally correlated excitatory input to a cartwheel or fusiform cell to modify its output. The significance of this depends in part on the nature of information carried by the population of parallel fibers. Little is known about the receptive fields of individual auditory granule cells, but granule cells receive both bouton and glomerular mossy terminals, terminating on one to four dendrites (Balakrishnan and Trussell 2008; Mugnaini et al. 1980a,b; Wright and Ryugo 1996). Clearly it will be necessary to determine the diversity of receptive fields for single auditory granule cells and their targets, as has been done in cerebellum (Chadderton et al. 2004; Jorntell and Ekerot 2006). However, whether or not single granule cells have narrow receptive fields of excitation, the requirement that cartwheel and fusiform cells integrate input from multiple parallel fibers to change their output could mean that these cells act as cellular detectors of specific combinations of sensory cues.

Distribution and strength of inhibition

Compared with the limited overlap of excitatory parallel fiber input, neighboring neurons frequently receive inhibitory input from common presynaptic partners. In dual recordings, ∼30% of spontaneous IPSCs detected in one cell occurred within 1 ms of sIPSCs detected in the other cell. Many of these synchronous sIPSCs occurred in bursts, indicating they were elicited by complex spikes in common presynaptic cartwheel cells. Stellate cells, another molecular layer inhibitory interneuron, might also have contributed to the incidence of synchronous IPSCs (Mugnaini 1985; Wouterlood et al. 1984). Additionally, we found in paired recordings that cartwheel cells possessed a 28% chance of synapsing onto a neighboring cartwheel cell and a 35% chance of synapsing onto a fusiform cell. Mancilla and Manis (2009) reported even higher connectivity rates in paired recordings from P12-18 rat DCN. Thus cartwheel cells, and possibly stellate cells, distribute inhibition profusely within local circuits. The morphology of cartwheel cell axons, which branch widely within a local area, is consistent with this role (Golding and Oertel 1997; Manis et al. 1994; Roberts et al. 2008; Zhang and Oertel 1993).

In a previous study, we showed that simple or complex spikes from single presynaptic cartwheel cells elicit IPSPs that block complex spike firing in postsynaptic cartwheel cells (Roberts et al. 2008). Here we found that simple and complex spikes in presynaptic cartwheel cells inhibited spontaneous firing in postsynaptic fusiform cells for ≥20 ms. Furthermore, bursts of IPSPs elicited by presynaptic spikes produced transient increases in the firing rate of fusiform cells ∼170 ms after the onset of the IPSP burst. Thus it may be that a complex spike from one cartwheel cell might temporarily synchronize firing across multiple fusiform cells. Indeed other studies have shown that inhibition can improve the precision and reproducibility of fusiform cell spike timing for periods exceeding 100 ms (Kanold and Manis 2005; Street and Manis 2007). Together these results indicate that individual cartwheel cells exert strong control over the activity of postsynaptic neurons.

Role of inhibition

Feedforward inhibition typically refers to cases in which afferent inputs terminate on both inhibitory interneurons and the principal cell targets of these interneurons. A stricter definition requires that single afferents contact both the inhibitory interneuron and the associated principal cell and that the afferent can trigger a spike in the inhibitory interneuron, a condition rarely met (Blitz and Regehr 2005; Pouille and Scanziani 2001). More commonly, feedforward inhibition is assumed when stimulation of multiple afferent fibers triggers an EPSP-IPSP sequence in the principal cell (Mittmann et al. 2005) as in the granule-cartwheel-fusiform cell circuit (Davis et al. 1996). Based on such a circuit, it was predicted that inhibition from cartwheel cells narrows the time window for integration of parallel fiber input in fusiform cells (Zhao et al. 2009). However, an EPSP-IPSP sequence evoked on stimulation of multiple afferent fibers does not by itself suggest inhibition is feedforward because the latter depends on particular synaptic relationships among afferents and their targets within the group of stimulated fibers. Indeed our data suggest that cartwheel cells provide feedforward inhibition only when sensory stimuli activate sets of parallel fibers that meet two criteria. First, a number of parallel fibers within the set should synapse onto the cartwheel cell, such that the summed input from these synapses drives the cartwheel cell to spike. Second, the same or, more likely, other parallel fibers within the set should synapse onto one or more of the postsynaptic partners of the cartwheel cell.

When the second of these criteria is not met, cartwheel cells will provide lateral inhibition to their postsynaptic partners. In other brain regions, lateral inhibition is known to contribute to the refinement of receptive fields (for example, see Arevian et al. 2008; Brosch and Schreiner 1997; Calford and Semple 1995; Cook and McReynolds 1998; Hartline et al. 1956; Kuffler 1953; Werblin and Dowling 1969). Among neurons receiving similar, but not identical, input, lateral inhibition dampens the activity of neurons that are not strongly excited, enhancing the capacity of circuits to distinguish between related inputs. Our data suggest that neighboring neurons in the DCN molecular layer can receive distinct sets of information, i.e., one neuron is likely to be more strongly driven by a particular sensory stimulus than its neighbors. If that neuron is a cartwheel cell, then an increase in its activity will induce lateral inhibition, diminishing activity in neighboring, postsynaptic neurons. If that neuron is a fusiform cell, then it is more likely to overcome any concurrent inhibition and increase its output to inferior colliculus. Because there are numerous cartwheel cells in the outer layers of DCN (Mugnaini 1985), their collective receptive fields for parallel fiber input are probably quite large, presumably larger than that of fusiform cells. This suggests that cartwheel cells can act as circuit-level filters, using lateral inhibition to limit the instances when parallel fiber input can effectively excite fusiform cells, thereby narrowing fusiform cell receptive fields and sharpening the output of the DCN. An important prediction of the lateral inhibition model is that there should be cases where activation of parallel fibers leads to inhibition in fusiform cells without preceding excitation. Consistent with this, in vivo recordings from cat DCN showed that stimulation of granule cell inputs frequently decreased the firing rate of fusiform cells over a time window coinciding with when the same stimuli increased the firing rate of cartwheel cells (Davis and Young 1997; Davis et al. 1996). Thus the nature of a particular sensory stimulus combined with the receptive fields of granule cells and the synaptic connection patterns of their parallel fibers likely determine the type of inhibition provided by the cartwheel cell.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DC-004450 and R37NS-28901 to L. O. Trussell and T32DK-007680 and T32DC-005945 to M. T. Roberts and a Tartar Trust fellowship to M. T. Roberts.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Donata Oertel for comments on the manuscript.

Present address of M. T. Roberts: Section of Neurobiology, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Aizenman and Linden, 1999.Aizenman CD, Linden DJ. Regulation of the rebound depolarization and spontaneous firing patterns of deep nuclear neurons in slices of rat cerebellum. J Neurophysiol 82: 1697–1709, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arevian et al., 2008.Arevian AC, Kapoor V, Urban NN. Activity-dependent gating of lateral inhibition in the mouse olfactory bulb. Nat Neurosci 11: 80–87, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan and Trussell, 2008.Balakrishnan V, Trussell LO. Synaptic inputs to granule cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 99: 208–219, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, 1993.Barbour B. Synaptic currents evoked in Purkinje cells by stimulating individual granule cells. Neuron 11: 759–769, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrebi and Mugnaini, 1991.Berrebi AS, Mugnaini E. Distribution and targets of the cartwheel cell axon in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the guinea pig. Anat Embryol 183: 427–454, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstad et al., 1984.Blackstad TW, Osen KK, Mugnaini E. Pyramidal neurones of the dorsal cochlear nucleus: a Golgi and computer reconstruction study in cat. Neuroscience 13: 827–854, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blitz and Regehr, 2005.Blitz DM, Regehr WG. Timing and specificity of feed-forward inhibition within the LGN. Neuron 45: 917–928, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosch and Schreiner, 1997.Brosch M, Schreiner CE. Time course of forward masking tuning curves in cat primary auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 77: 923–943, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calford and Semple, 1995.Calford MB, Semple MN. Monaural inhibition in cat auditory cortex. J Neurophysiol 73: 1876–1891, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadderton et al., 2004.Chadderton P, Margrie TW, Hausser M. Integration of quanta in cerebellar granule cells during sensory processing. Nature 428: 856–860, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements and Bekkers, 1997.Clements JD, Bekkers JM. Detection of spontaneous synaptic events with an optimally scaled template. Biophys J 73: 220–229, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook and McReynolds, 1998.Cook PB, McReynolds JS. Lateral inhibition in the inner retina is important for spatial tuning of ganglion cells. Nat Neurosci 1: 714–719, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis et al., 1996.Davis KA, Miller RL, Young ED. Effects of somatosensory and parallel-fiber stimulation on neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 76: 3012–3024, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis and Young, 1997.Davis KA, Young ED. Granule cell activation of complex-spiking neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 17: 6798–6806, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis and Young, 2000.Davis KA, Young ED. Pharmacological evidence of inhibitory and disinhibitory neuronal circuits in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 83: 926–940, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davson and Segal, 1996.Davson H, Segal MB. Chemical composition and secretory nature of the fluid. In: Physiology of the CSF and Blood-Brain Barriers. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 1996, p. 11–24 [Google Scholar]

- Dittman et al., 2000.Dittman JS, Kreitzer AC, Regehr WG. Interplay between facilitation, depression, and residual calcium at three presynaptic terminals. J Neurosci 20: 1374–1385, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt et al., 2002.Dodt HU, Eder M, Schierloh A, Zieglgansberger W. Infrared-guided laser stimulation of neurons in brain slices. Sci STKE 2002: PL2, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet and Ryugo, 1997.Doucet JR, Ryugo DK. Projections from the ventral cochlear nucleus to the dorsal cochlear nucleus in rats. J Comp Neurol 385: 245–264, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekerot and Jorntell, 2001.Ekerot CF, Jorntell H. Parallel fiber receptive fields of Purkinje cells and interneurons are climbing fiber-specific. Eur J Neurosci 13: 1303–1310, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding and Oertel, 1997.Golding NL, Oertel D. Physiological identification of the targets of cartwheel cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 78: 248–260, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartline et al., 1956.Hartline HK, Wagner HG, Ratliff F. Inhibition in the eye of Limulus. J Gen Physiol 39: 651–673, 1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey and Napper, 1991.Harvey RJ, Napper RM. Quantitative studies on the mammalian cerebellum. Prog Neurobiol 36: 437–463, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isope and Barbour, 2002.Isope P, Barbour B. Properties of unitary granule cell—Purkinje cell synapses in adult rat cerebellar slices. J Neurosci 22: 9668–9678, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorntell and Ekerot, 2006.Jorntell H, Ekerot CF. Properties of somatosensory synaptic integration in cerebellar granule cells in vivo. J Neurosci 26: 11786–11797, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanold and Manis, 2005.Kanold PO, Manis PB. Encoding the timing of inhibitory inputs. J Neurophysiol 93: 2887–2897, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim and Trussell, 2007.Kim Y, Trussell LO. Ion channels generating complex spikes in cartwheel cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 97: 1705–1725, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim and Trussell, 2009.Kim Y, Trussell LO. Negative shift in the glycine reversal potential mediated by a Ca2+- and pH-dependent mechanism in interneurons. J Neurosci 29: 11495–11510, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuffler, 1953.Kuffler SW. Discharge patterns and functional organization of mammalian retina. J Neurophysiol 16: 37–68, 1953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancilla and Manis, 2009.Mancilla JG, Manis PB. Two distinct types of inhibition mediated by cartwheel cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 102: 1287–1295, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manis, 1990.Manis PB. Membrane properties and discharge characteristics of guinea pig dorsal cochlear nucleus neurons studied in vitro. J Neurosci 10: 2338–2351, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manis et al., 1994.Manis PB, Spirou GA, Wright DD, Paydar S, Ryugo DK. Physiology and morphology of complex spiking neurons in the guinea pig dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 348: 261–276, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May, 2000.May BJ. Role of the dorsal cochlear nucleus in the sound localization behavior of cats. Hear Res 148: 74–87, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittmann et al., 2005.Mittmann W, Koch U, Hausser M. Feed-forward inhibition shapes the spike output of cerebellar Purkinje cells. J Physiol 563: 369–378, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini, 1985.Mugnaini E. GABA neurons in the superficial layers of the rat dorsal cochlear nucleus: light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. J Comp Neurol 235: 61–81, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini et al., 1980a.Mugnaini E, Osen KK, Dahl AL, Friedrich VL, Jr, Korte G. Fine structure of granule cells and related interneurons (termed Golgi cells) in the cochlear nuclear complex of cat, rat and mouse. J Neurocytol 9: 537–570, 1980a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini et al., 1980b.Mugnaini E, Warr WB, Osen KK. Distribution and light microscopic features of granule cells in the cochlear nuclei of cat, rat, and mouse. J Comp Neurol 191: 581–606, 1980b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel and Wu, 1989.Oertel D, Wu SH. Morphology and physiology of cells in slice preparations of the dorsal cochlear nucleus of mice. J Comp Neurol 283: 228–247, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel et al., 1990.Oertel D, Wu SH, Garb MW, Dizack C. Morphology and physiology of cells in slice preparations of the posteroventral cochlear nucleus of mice. J Comp Neurol 295: 136–154, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel and Young, 2004.Oertel D, Young ED. What's a cerebellar circuit doing in the auditory system? Trends Neurosci 27: 104–110, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva et al., 2000.Oliva AA, Jr, Jiang M, Lam T, Smith KL, Swann JW. Novel hippocampal interneuronal subtypes identified using transgenic mice that express green fluorescent protein in GABAergic interneurons. J Neurosci 20: 3354–3368, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen, 1970.Osen KK. Course and termination of the primary afferents in the cochlear nuclei of the cat. An experimental anatomical study. Arch Ital Biol 108: 21–51, 1970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen et al., 1995.Osen KK, Storm-Mathisen J, Ottersen OP, Dihle B. Glutamate is concentrated in and released from parallel fiber terminals in the dorsal cochlear nucleus: a quantitative immunocytochemical analysis in guinea pig. J Comp Neurol 357: 482–500, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham and Kim, 1995.Parham K, Kim DO. Spontaneous and sound-evoked discharge characteristics of complex-spiking neurons in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the unanesthetized decerebrate cat. J Neurophysiol 73: 550–561, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkel et al., 1967.Perkel DH, Gerstein GL, Moore GP. Neuronal spike trains and stochastic point processes. II. Simultaneous spike trains. Biophys J 7: 419–440, 1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, 2006.Perkins KL. Cell-attached voltage-clamp and current-clamp recording and stimulation techniques in brain slices. J Neurosci Methods 154: 1–18, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portfors and Roberts, 2007.Portfors CV, Roberts PD. Temporal and frequency characteristics of cartwheel cells in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the awake mouse. J Neurophysiol 98: 744–756, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouille and Scanziani, 2001.Pouille F, Scanziani M. Enforcement of temporal fidelity in pyramidal cells by somatic feed-forward inhibition. Science 293: 1159–1163, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts et al., 2008.Roberts MT, Bender KJ, Trussell LO. Fidelity of complex spike-mediated synaptic transmission between inhibitory interneurons. J Neurosci 28: 9440–9450, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio and Juiz, 2004.Rubio ME, Juiz JM. Differential distribution of synaptic endings containing glutamate, glycine, and GABA in the rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 477: 253–272, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio and Wenthold, 1997.Rubio ME, Wenthold RJ. Glutamate receptors are selectively targeted to postsynaptic sites in neurons. Neuron 18: 939–950, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo et al., 2003.Ryugo DK, Haenggeli CA, Doucet JR. Multimodal inputs to the granule cell domain of the cochlear nucleus. Exp Brain Res 153: 477–485, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo and May, 1993.Ryugo DK, May SK. The projections of intracellularly labeled auditory nerve fibers to the dorsal cochlear nucleus of cats. J Comp Neurol 329: 20–35, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd and Raastad, 2003.Shepherd GM, Raastad M. Axonal varicosity distributions along parallel fibers: a new angle on a cerebellar circuit. Cerebellum 2: 110–113, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd et al., 2002.Shepherd GM, Raastad M, Andersen P. General and variable features of varicosity spacing along unmyelinated axons in the hippocampus and cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 6340–6345, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore and Zhou, 2006.Shore SE, Zhou J. Somatosensory influence on the cochlear nucleus and beyond. Hear Res 216– 217: 90–99, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg et al., 2005.Silberberg G, Grillner S, LeBeau FE, Maex R, Markram H. Synaptic pathways in neural microcircuits. Trends Neurosci 28: 541–551, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith and Rhode, 1985.Smith PH, Rhode WS. Electron microscopic features of physiologically characterized, HRP-labeled fusiform cells in the cat dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 237: 127–143, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanyants and Chklovskii, 2005.Stepanyants A, Chklovskii DB. Neurogeometry and potential synaptic connectivity. Trends Neurosci 28: 387–394, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street and Manis, 2007.Street SE, Manis PB. Action potential timing precision in dorsal cochlear nucleus pyramidal cells. J Neurophysiol 97: 4162–4172, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland et al., 1998.Sutherland DP, Masterton RB, Glendenning KK. Role of acoustic striae in hearing: reflexive responses to elevated sound sources. Behav Brain Res 97: 1–12, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller and Godfrey, 1994.Waller HJ, Godfrey DA. Functional characteristics of spontaneously active neurons in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus in vitro. J Neurophysiol 71: 467–478, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei et al., 2010.Wei L, Ding D, Sun W, Xu-Friedman MA, Salvi R. Effects of sodium salicylate on spontaneous and evoked spike rate in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 267: 54–60, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werblin and Dowling, 1969.Werblin FS, Dowling JE. Organization of the retina of the mudpuppy, Necturus maculosus. II. Intracellular recording. J Neurophysiol 32: 339–355, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouterlood et al., 1984.Wouterlood FG, Mugnaini E, Osen KK, Dahl AL. Stellate neurons in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus studies with combined Golgi impregnation and electron microscopy: synaptic connections and mutual coupling by gap junctions. J Neurocytol 13: 639–664, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright and Ryugo, 1996.Wright DD, Ryugo DK. Mossy fiber projections from the cuneate nucleus to the cochlear nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 365: 159–172, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young et al., 1995.Young ED, Nelken I, Conley RA. Somatosensory effects on neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 73: 743–765, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang and Oertel, 1993.Zhang S, Oertel D. Cartwheel and superficial stellate cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus of mice: intracellular recordings in slices. J Neurophysiol 69: 1384–1397, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang and Oertel, 1994.Zhang S, Oertel D. Neuronal circuits associated with the output of the dorsal cochlear nucleus through fusiform cells. J Neurophysiol 71: 914–930, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao et al., 2009.Zhao Y, Rubio ME, Tzounopoulos T. Distinct functional and anatomical architecture of the endocannabinoid system in the auditory brain stem. J Neurophysiol 101: 2434–2446, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.