Abstract

Background

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are highly prevalent and associated with non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy, decreased health care utilization and poor HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected individuals.

Objectives

To systematically review studies assessing the impact of AUDs on: (1) medication adherence, (2) health care utilization and (3) biological treatment outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).

Data Sources

Six electronic databases and Google Scholar were queried for articles published in English, French and Spanish from 1988 to 2010. Selected references from primary articles were also examined.

Review Methods

Selection criteria included: 1) AUD and adherence (N=20); 2) AUD and health services utilization (N=11); or 3) AUD with CD4 count or HIV-1 RNA treatment outcomes (N=10). Reviews, animal studies, non-peer reviewed documents and ongoing studies with unpublished data were excluded. Studies that did not differentiate HIV+ from HIV- status and those that did not distinguish between drug and alcohol use were also excluded. Data were extracted, appraised and summarized.

Data Synthesis and Conclusions

Our findings consistently support an association between AUDs and decreased adherence to antiretroviral therapy and poor HIV treatment outcomes among HIV-infected individuals. Their effect on health care utilization, however, was variable.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Alcohol Use Disorders, Systematic Review, Adherence, Health Care Utilization

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and HIV are both widespread, but result in intertwined global epidemics that generate significant morbidity and mortality. HIV/AIDS results in more than 2 million deaths annually and has caused 25 million cumulative deaths since the beginning of the epidemic (World Health Organization, 2009). Similarly, there are 1.8 million alcohol-related deaths annually world-wide (World Health Organization, 2007). In the U.S., 14 million Americans meet DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence and even more experience problems with alcohol (Isaki and Kresina, 2000). While AUDs alone cause significant physical, mental and social impairment, they also exacerbate other co-morbid conditions like HIV due to decreased adherence with medications (Hendershot et al., 2009), decreased health care utilization (Zarkin et al., 2004) and increased HIV risk behaviors associated with disinhibition (Fisher et al., 2007; Justus et al., 2000). In this way, AUDs and HIV act synergistically at the individual and societal level to negatively impact health.

AUDs are generally defined by ingestion of alcohol over a period of time and in patterns that lead to problems with health, personal relationships, work or the law. Most literature on the topic employs either the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (DSM-IV) or the International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) criteria to define alcohol dependence, abuse, or “harmful use” but many other definitions exist. In 2001-2002, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) estimated that 4.65% of the US population were alcohol abusers (Grant et al., 2004), while more recent data from the WHO shows that 11% of Americans are heavy drinkers (World Health Organization, 2004). Though already widespread in the general population, AUDs seem to be even more common among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) (Balla et al., 1994; Galvan et al., 2002). The prevalence of AUDs among PLWHA is 2-4 times higher than among uninfected populations (Petry, 1999) and ranges from 8% to 41% (Cook et al., 2001; Lefevre et al., 1995; Tucker et al., 2003). These prevalence estimates likely reflect the diverse definitions and measurements of alcohol problems used. For example, a U.S. probability survey of PLWHA receiving medical care found that 53% of participants reported any alcohol ingestion in the past month; 15% of these were classified as heavy drinkers (Galvan et al., 2002). This rate is twice that estimated among the general population (Greenfield et al., 2000). Irrespective of the definition used, AUDs among HIV-infected persons are common and alcohol consumption has been shown to decrease overall survival in this population (Braithwaite et al., 2007).

AUDs have many important public health consequences because of alcohol's association with: 1) direct deleterious consequences on one's health; 2) increased HIV risk-taking behaviors among PLWHA, thereby potentially resulting in increased HIV transmission (Shuper et al., 2009a; Woolf and Maisto, 2009); 3) decreased adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) that may contribute to development of drug resistance mutations (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2002); 4) delay in HIV diagnosis and subsequent decreased health care utilization (Zarkin et al., 2004); 5) increased risk for Hepatitis C Virus infection (Cheng et al., 2007); 6) acceleration of cognitive decline (Anand et al., 2010; Green et al., 2004); 7) higher prevalence of mental illness (RachBeisel et al., 1999) and 8) overall increased mortality (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2002). AUDs alone have profound adverse health consequences but for PLWHAs, these consequences are amplified.

The impact of AUDs on HIV prevalence (Kalichman et al., 2007) and HIV risk behaviors has recently been reviewed (Shuper et al., 2009b). In this paper, we extend findings from PLWHAs and AUDs and systematically review the impact of AUDs on other outcomes: adherence to antiretroviral therapy, health care utilization, and biological treatment outcome measures.

2. Methods

2.1 Data Search

Briefly, PubMed, Cochrane, Web of Knowledge, SCOPUS, CINAHL, and Yale University Library were queried for peer-reviewed original human research published in English, French or Spanish from 1988 to 2009. Google Scholar and primary references were also reviewed for details or other articles. The keywords and their combinations used in the search are available as an electronic appendix1.

2.2 Study Selection and Inclusion/Exclusion criteria

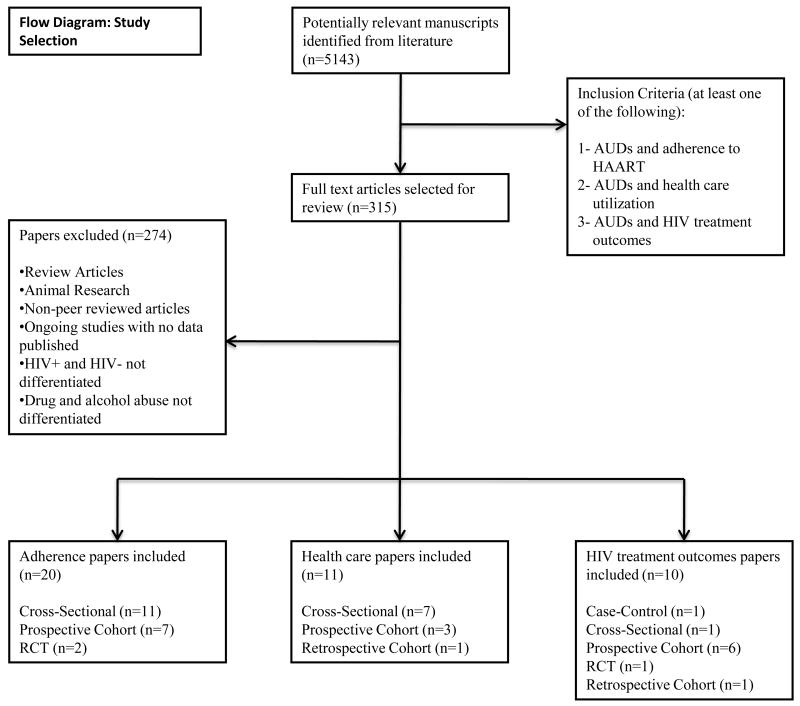

Figure 1 provides the CONSORT flow for systematic reviews. The original search resulted in more than 5143 documents for which 315 articles met the following inclusion criteria: 1) alcohol use and HAART adherence; 2) alcohol use and health services utilization; or 3) alcohol use and biological HIV treatment outcome measures (CD4 count and HIV-1 RNA). Of these, 274 were subsequently excluded because they were either review articles, non-peer reviewed newspaper articles and letters, were not human studies, described ongoing studies with no data published or lacked the stated outcomes of interest. Manuscripts were also excluded if the outcome of interest was analyzed without differentiating HIV-infected from HIV-uninfected subjects or if alcohol and drug use were not distinguished.

Fig. 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

2.3 Data Extraction

Standardized data collection forms were used to extract all data, including: study authors; study site; year and duration of study; study design; population characteristics; sample size; type of measurement used to define AUDs, antiretroviral adherence, or healthcare utilization; type of health care use examined; and biological HIV treatment outcome measures. When the article used more than one definition for AUDs, antiretroviral adherence, healthcare utilization or HIV treatment outcomes, all definitions were included. In cases where no standardized definition of AUD was used, the terms used by the authors were noted.

2.4 Definitions and measures

2.4.1 Measures of Alcohol Use

AUDs represent an array of distinct conditions and are defined by diagnostic, epidemiological or screening criteria that have considerable overlap. In addition to DSM-IV and ICD-10 definitions for AUDs, alcohol use is additionally categorized by the number of drinks (e.g., heavy, moderate, light) and its impact on health (e.g., hazardous drinking, harmful, at-risk, binge drinking, etc.). Standardized and non-standardized assessment tools define many of these drinking thresholds based on the amount of alcohol consumed. We therefore present the definitions used by the authors, including the terminology, assessment tool and their threshold (not always consistent with existing standards).

Categories of AUDs encountered in these articles included: alcohol dependence (by DSM-IV and DSM-III criteria), alcohol problems (by ICD-9-CM coding), hazardous drinking, heavy drinking, heavy alcohol use, at-risk drinking, alcohol use frequency, light/moderate/severe drinking (using WHO definition), and binge drinking. Some studies used multiple measures in parallel (e.g., by combining heavy drinking and hazardous drinking); one study created an Alcohol Factor, which included problem drinking, negative consequences of drinking and total alcohol consumption. Some studies failed to provide a definition for their alcohol measures at all and simply defined alcohol use as having had any alcohol. Because of the wide array of alcohol use measures used by the investigators, we used the term “alcohol use disorders” (AUDs) for uniformity and placed the exact term used by the authors in parentheses.

2.4.2 Antiretroviral adherence measurements

Multiple methods, both validated and unvalidated, were used to assess HAART adherence (Table 1). They included self-reports, hospital or clinic records, pharmacy records, pill counts and electronic monitoring systems. Adherence was reported either as a continuous or binary measure (adherent vs. non-adherent) according to a specified threshold. In the reviewed studies, adherence was reported either in association with AUDs or as the proportion of the sample meeting a specified adherence threshold. Both of these measures were extracted and are presented in Table 12. Adherence threshold measurements vary considerably and may involve a single time point or are longitudinal. Some studies used a number of missed doses as a cut-off; others used ≥95% adherence, 100% adherence, or a pre-defined response to a self-report questionnaire. Time until regimen discontinuation was also used. The time period over which adherence was assessed ranged from the previous 24 hours to the previous 6 months. There was absolutely no uniformity in adherence measurements so drawing comparisons between studies was challenging.

Table 1.

Impact of Alcohol Use Disorders on HAART Adherence: Study Characteristics

| Author, Publication year, Location | Study Design and Evaluation Period | Study Population, Sample Size | Adherence: measurement, definition and total adherence | Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) | Impact of AUD on Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braithwaite, 2005, U.S | Cross-Sectional (2002-2003) | 2,774 HIV+ vs. 1930 HIV- veterans | Definition: 100% adherence to HAART Total adherence= 70.7% |

Binge drinkers defined as: >5 drinks per day in past 30 days Non-binge drinkers defined as: ≤4 drinks per day in past 30 days |

Decreased adherence with binge drinking: AOR= 3.9 (2.1–7.4) at 95% CI |

| Chander, 2006 U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1998-2003) | 1171 HIV+ persons | Definition: < 2 missed doses of HAART | Hazardous drinking defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion |

Decreased adherence with hazardous drinking: AOR=0.46 (0.34-0.63) at 95% CI |

| Chesney, 2000 U.S | Cross Sectional Survey (1997 | 75 HIV+ persons | Definition: ≤1 missed doses of HAART Total adherence=64% |

Number of drinks in past 30 days Number of drinks per day |

Median consumption of alcoholic drinks significantly higher in non-adherent vs. adherent subjects. Mann-Whitney z=2.23, P <0.03 |

| Conen, 2009 Switzerland | Prospective Observational Cohort (2005-2007) | 4519 HIV+ on HAART | Definitions: 0, 1, 2 or ≥2 missed doses of HAART Total adherence: For 0 missed doses=77% For 1 missed dose=13.7% For 2 missed doses=5.1% For ≥ 2 missed doses=4.2% |

WHO International guide for alcohol consumption and related harm: Light, Moderate, Severe Drinking. | Decreased adherence (≥1 missed doses) in severe drinking compared to all other drinking categories including: Non-drinkers: AOR=0.33 (0.22-0.49), P <0.001 |

| Cook, 2001 U.S | Cross Sectional Survey (1997-1998) | 212 HIV+ outpatients | Definition:: <1 missed dose of HAART (Except if meds were taken “all of the time” or “nearly all the time” in the previous week) | Hazardous Drinking defined as a score of ≧8 on AUDIT Heavy Drinking defined as: W: ≧12 drinks per week M: ≧16 drinks per week Binge Drinking defined as: W: >5 drinks per day at least once per month M: >6 drinks per day at least once per month |

Decreased past-week adherence with hazardous drinking: AOR=2.64 (1.07-6.53) at 95% CI No association with past day adherence (P>0.05) Decreased past-week adherence with Heavy drinking: AOR=4.70 (1.49-14.48) at 95% CI No association with past day adherence (P>0.05) No association with Binge Drinking |

| Friedman, 2009, U.S | Cross-Sectional Study (2004-2005) | 429 HIV+ on HAART with low SES and homelessness | Definition:: ≤1 missed doses of HAART | Alcohol Abuse (diagnosed with CDQ) | No impact of Alcohol abuse on adherence. Adherence in abusers (79,5%) comparable to non-abusers (74.5%, P>0.05) |

| Golin, 2002, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1998-1999) | 117 HIV+ patients from county hospital | Definition 1: 95% Adherence to HAART Definition 2: % Prescribed doses taken Total adherence: <5% (using definition 1) |

Alcohol use in past 30 days | Decreased adherence (% prescribed doses taken) in alcohol users (66.3%) compared to non-users (74.2%), P<0.01 |

| Hinkin, 2004, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1998) | 148 HIV+ persons from community and clinics | Definition: ≧95% adherence to HAART Total adherence: 53% of subjects above 50 and 26% of subjects below 50 |

Alcohol Abuse/Alcohol Dependence by DSM-IV | No impact of Alcohol abuse/dependence on decreased adherence. Likelihood of less than 95% adherence not significantly higher in alcohol abusers compared to non-abusers. [x2(1.114)=0.73, P=0.58] |

| Kim, 2007, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (2001-2005) | 266 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems | Definition:: Non-adherence defined as HAART discontinuation defined as stopping HAART for more than 30 days in 6 months Total HAART Discontinuation=17% |

Hazardous Drinking (reported as heavy alcohol consumption) defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion |

No impact of hazardous drinking on HAART discontinuation HAART discontinuation comparable in hazardous drinkers (19%) vs. non-hazardous drinkers (16%) AOR=1.01 (0.63, 1.63) at 95% CI |

| Kleeberger, 2001, U.S | Cross Sectional Study (1998-1999) | 539 Homosexual or bisexual HIV+ men | Definition: 100% adherence to HAART Total adherence= 77.7% |

Hazardous drinking defined as: ≧14 drinks per week |

No impact of hazardous drinking on decreased adherence. Adherence in hazardous drinkers (70.4%) comparable non-hazardous drinking (78.8%) p>0.05 |

| Michel, 2009, France | Cross sectional study (2003) | 2340 HIV+ outpatients | Definition: Highly Adherent= positive response to self-report questions Poorly Adherent (any response pattern that is not consistent with Highly adherent) |

Harmful Alcohol consumption by multiple measures: 1-CAGE score: ≥2 2-Binge drinking defined as: >6 drinks per day at least twice per month 3-AUDIT score: W: ≥4, M: ≥5 |

Decreased adherence with all three indicators of harmful alcohol consumption, P<0.001 |

| Murphy, 2002 U.S | Cross sectional data from a Prospective Observational Cohort (1997-1999) | 52 HIV+ women with children | Definition 1: ≧95% Adherence to dosing by self-report Definition 2: ≧95% Adherence to schedule by self-report Definition 3: % Prescribed doses taken Total adherence: 43%(by pill count) and 56%(by self-report) |

Any Alcohol used in previous 3 months according to NIDA RBA Questionnaire | Decreased past-3 day adherence to schedule with any alcohol use in past 3 months. OR=0.199, P < 0.05 All other measure did not reach statistical significance |

| Murphy, 2004, U.S | Cross Sectional Study (1999-2004) | 115 Non-adherent HIV+ persons from community | Definition: ≧95% Adherence to HAART Total adherent: 3 day (58.3%), previous week (34.8%) and previous month (26.1%) |

Frequency of alcohol use in past 3 months | Decreased past month adherence with increasing alcohol use frequency AOR=0.51 (0.33-0.79) at 95% CI Past 3 day and past week adherence not reported in association with alcohol |

| Parsons, Golub, 2007, U.S | Randomized Controlled Trial (2002-2005): Motivational interviewing + Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs. Standard educational session to improve adherence |

143 HIV+ hazardous drinkers | Definition 1: Percent dose adherence=% days with perfect adherence Definition 2: Percent day adherence=% days with perfect adherence Total percent dose adherence at baseline: 78% (intervention) vs. 85.1% (control) Total percent day adherence at baseline: 74.1% (intervention) vs. 81.4% (control) |

Hazardous drinking defined as: W: ≧12 drinks per week M: ≧16 drinks per week |

Increased percent dose adherence at 3 months in intervention group compared to control group [F(1,107) = 4.0; P < 0.05] Increased percent day adherence at 3 months in intervention group compared to control group [[F(1,111) = 4.1; P < 0.05] At 6 months, no significant increase P>0.05 |

| Parsons, Rosof, 2007, U.S | Cross Sectional Study (2002-2005) | 272 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems | Definition: ≧95% Adherence to HAART Total Adherence=43% |

“Alcohol Factor” composite of alcohol related problems and alcohol consumption over past 30 days Alcohol related problems assessed with AUDIT* and Drinker Inventory of Negative Consequences tool |

Decreased adherence with increasing Alcohol Factor AOR=0.55 (0.39-0.77), at 95% CI |

| Peretti-Watel 2005, France | Cross Sectional Study (2003) | 2484 HIV+ outpatients on HAART | Definition: Highly Adherent= positive response to self-report questions Poorly Adherent (any response pattern that is not consistent with Highly adherent) Total Highly Adherent=59.5% |

Regular use defined as: ≥2 drinks per week Binge drinking defined as: ≥5 drinks at least twice per month CAGE score: ≥2 |

Decreased adherence among those with positive CAGE, binge drinking and regular use. Poorly adherent persons more likely to be CAGE score ≥2 (18.5% vs. 8.2%), binge drinkers (14.2% vs. 6.2%) and regular users (35.7% vs. 27.9%) than highly adherent P<0.003 |

| Samet, 2004, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1997-2001) | 349 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems (205 on HAART) | Definition: 100% adherence to HAART Total adherence=66% |

Hazardous drinking (reported as At-risk drinking) defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion Moderate drinking defined as alcohol consumption below hazardous drinking levels |

Decreased adherence with hazardous drinking vs. abstinence AOR=3.6 (2.1–6.2) at 95% CI Decreased adherence with moderate drinking vs. abstinence AOR=3.0 (2.0-4.5) at 95% CI |

| Samet, 2005, U.S | Randomized Controlled Trial (1997-2000): Multi-component behavioral intervention vs. Standard care for HIV infection |

151 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems | Definition 1: ≥95% adherence over past 30 days Definition 2: 100% adherence over past 3 days Definition 3: Adherence as a continuous measure over past 30 days Total adherence at baseline (as per definition 1)= 69% for control vs.68% for intervention Total adherence at baseline (as per definition 2)= 65% for control vs. 58% intervention |

Hazardous drinking defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion |

Neither measure of adherence was increased in intervention group compared to control group in the short term (1 to 6 months) and the long term (12-13 months), P≥0.39 |

| Samet, 2007, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1997-2003) | 595 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems (354 on HAART) | Definition: 100% adherence to HAART Total adherence=70% |

Hazardous drinking (reported as heavy alcohol consumption) defined as: W+M above 66: ≧7 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion M below 66: ≧14 drinks per week or 5 drinks per occasion |

Decreased adherence to HAART among hazardous drinkers compared to non-hazardous drinkers P<0.0007 |

| Tucker, 2003, U.S | Cross sectional analysis of a prospective Observational Study | 1910 HIV+ persons | Definition: 100% adherence to HAART Total adherence=46% |

Heavy drinking defined as: ≥5 drinks per occasion, one 1 to 4 days in past month Frequent heavy drinking defined as: ≥5 drinks per occasion, more than 5 days in past month |

Decreased adherence with heavy drinking AOR=1.7 (1.3-2.3) at 95% CI Decreased adherence associated with heavy drinking associated with: AOR=2.7 (1.7-4.5) at 95% |

AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio

ASI: Addiction Severity Index

CAGE: An alcohol screening questionnaire

ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

IRR: Incidence Rate Ratio

SCID-IV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

RR: Relative Risk

W=women, M=men

2.4.3 Healthcare utilization measures

Data on health care utilization were extracted and classified as outpatient visits (or ambulatory visits), Emergency Department (ED) visits, hospitalizations, being prescribed HAART and “other” measures of health care use (Table 2)3.

Table 2.

Impact of Alcohol Use Disorders on Health Care Utilization: Study Characteristics

| Author, Publication year, Location | Study Design and Evaluation Period | Study Population, Sample Size | Alcohol Use Disorder Measure | Impact of AUD on Health Care Utilization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient Visits | Emergency Department (ED) Visits | Hospitalizations | HAART utilization | Other measures of health care use | ||||

| Chander, 2006, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1998-2003 | 1171 HIV+ persons in urban areas | Hazardous drinking defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion |

X | X | X | Decreased use of HAART with hazardous drinking AOR=0.65 (0.51-0.82) at 95% CI |

X |

| Cunningham CO, 2006, U.S | Cross Sectional Study (1999-2001) | 238 HIV+ persons | Binge drinking defined as: ≥5 drinks per day at least twice per month | Increased regular outpatient visits with binge drinking AOR=2.61, P=0.05 |

No association found P>0.05 |

No association found P>0.05 |

Decreased HAART utilization with binge drinking P<0.05 (AOR not provided) |

No association found with: Regular CD4 counts Taking PCP prophylaxis Good quality of care and good access to care P>0.05 |

| Cunningham CO, 2007, U.S | Cross Sectional Study (2001-2003) | 610 HIV+ persons | Heavy drinking defined as: ≥5 drinks on at least 1 day in past 30 days |

No association found (AOR not shown) | Increased ED visits with heavy drinking AOR=1.46 (1.02-2.09) at 95% CI | No association found (AOR not shown) | X | X |

| Cunningham, WE, 2006, U.S | Comparative Cross Sectional Study Sample 1: 2001-2003 Sample 2: 1996-1998 |

Sample 1: 1286 underserved HIV+ persons Sample 2: 2267 HIV+ people receiving standard care |

Heavy drinking defined as: ≥5 drinks on at least 1 day in past 30 days |

Decreased ambulatory visits with heavy drinking in sample 1 AOR=1.74 (1.23-2.45) at 95% CI, but not in sample 2 (AOR=1) | X | X | X | X |

| Gordon, 2006, U.S | Retrospective Observational Cohort (1999-2000) | 881 HIV+ veterans | Hazardous drinking defined as: Score ≧8 using AUDIT or having ≥6 drinks on one occasion in the past month (binge drinking) |

Decreased likelihood of having 2 or more outpatient visits with hazardous drinking AOR=0.67 (0.49-0.92) at 95% CI |

No association found for 1 or more ED visits AOR=1.02 (0.75–1.39) at 95% CI | Increased likelihood of having one or more hospitalizations with hazardous drinking AOR= 1.05 (1.08-2.12) at 95% CI |

X | X |

| Josephs, 2010, U.S | Cross Sectional Study (2003) | 951 HIV+ persons | Hazardous drinking defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion Binge drinking defined as: ≥5 drinks on at least 1 day in past 30 days |

X | Increased ED visits with no alcohol use compared to hazardous/binge drinking AOR=1.94 (1.06–3.57) at 95% CI | No association found for hospital admission from ED | X | X |

| Kim, 2006, U.S | Cross Sectional Study Analysis of a Prospective Observational Cohort (1997-2000) | 349 HIV+ people with alcohol problems | Alcohol Addiction Severity (ASI) for alcohol using ASI | Decreased ambulatory visits with increasing alcohol addiction severity IRR=1.92 (1.25-2.94) at 95% CI | No association found IRR=1.13 (0.67-1.93) at 95% CI |

No association found IRR=1.54 (0.69-3.44) at 95% CI |

X | X |

| Kraemer, 2006, US | Prospective Observational Cohort (1998-2003) | 16048 HIV+ veterans | Alcohol problems defined as: An alcohol-related ICD-9-CM diagnosis |

Increased outpatient total visits with alcohol problems IRR=2.17 (2.06-2.28) at 95% CI No association found for General medicine visits IRR=1.58 (1.51-1.65) at 95% CI |

Increased ED visits with alcohol problems IRR=1.46 (1.35-1.58) at 95% CI Only ED visits that did not result in a hospitalization were included to avoid double counting |

Increased hospitalizations with alcohol problems IRR=1.46 (1.30-1.64) at 95% CI | X | Increased mental health care visits with alcohol problems IRR=1.96 (1.77-2.17) at 95% CI |

| Masson, 2004, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1994-1996) | 190 HIV+ people with a substance use disorder | Alcohol Addiction Severity (ASI) for alcohol using ASI | No association found P>0.05 |

Increased ED visits with increasing alcohol addiction severity (only squared term was significant) P<0.01 | No association found P>0.05 |

X | X |

| Palepu, Horton, 2005 U.S | Cross sectional analysis (1997-2001) | 349 HIV+ people with alcohol problems | Alcohol Dependence by Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS) | X | X | Increased likelihood of hospitalizations with alcohol dependence AOR=1.02 (1.00-1.05) at 95% CI | X | X |

| Weaver, 2008, U.S | Cross sectional analysis (2000-2002) | 803 HIV+ people with mental health (MH) and substance abuse (SA) disorders | Alcohol Dependence by SCID | X | X | X | X | Decreased SA outpatient use RR=0.71 (0.44-0.99) at 95% CI Decreased attendance to SA self-help groups RR=0.75 (0.51-0.99) at 95% CI Decreased use of residential SA care RR=0.37 (0.13-0.69) at 95% CI No association with MH services use. |

X=Not reported

AOR=Adjusted Odds Ratio

ASI: Addiction Severity Index

CAGE: An alcohol screening questionnaire

ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

IRR: Incidence Rate Ratio

SCID-IV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

RR: Relative Risk

W=women, M=men

2.4.4 Biological HIV treatment outcome measures

Biological HIV treatment outcome measures included CD4 count (cells/mL) and viral load (HIV-1 RNA copies/mL) levels. CD4 lymphocyte counts were characterized either as a binary measure or by absolute changes from baseline. HIV-1 RNA levels were categorized into virologic suppression (HIV-1 RNA<400 or <500), detectable viral load (HIV-1 RNA>400 or >500) or as log transformation change from baseline.

3. Results

3.1 The impact of alcohol use disorders on HAART adherence

Twenty studies met final inclusion criteria for this category (see Table 1). Study designs included prospective observational cohorts (N=7), cross-sectional analyses (N=11) and randomized controlled trials (N=2).

3.1.1 HAART adherence in prospective observational cohorts

Decreased HAART adherence among those with AUDs was reported in 5 of 7 longitudinal studies. Of these, three large cohorts of PLWHA used missing 1 or 2 doses as their adherence measurement, but the timeframe over which adherence was assessed differed substantially (e.g., past week, 2 weeks or 4 weeks). AUD measurements (heavy drinking, hazardous drinking or severe drinking) differed substantially as well (Chander et al., 2006; Conen et al., 2009; Tucker et al., 2004). Two other studies also found decreasing levels of adherence in association with alcohol (Golin et al., 2002; Samet et al., 2004) but they used smaller cohorts. One study found poor adherence overall in their sample; nonetheless, subjects using “any alcohol use in the prior 30 days”, had significantly lower adherence (66.3%) than non-users (74.2%) (Golin et al., 2002).

Two prospective cohort studies found no significant association between HAART adherence and AUDs. The measurement for adherence, however, may be responsible for the differing outcomes. In one study of 266 PLWHA, non-adherence was defined as medication discontinuation (Kim et al., 2006); this definition applies to non-persistence rather than non-adherence; non-adherence is typically characterized by missing a percentage of prescribed doses while non-persistence involves a pre-specified “gap” in treatment. This analysis was further complicated by the high concomitant prevalence of depression and its correlation with drug and alcohol use disorders. Of the 17% who discontinued HAART, it was depression, but not hazardous drinking, that was associated non-persistence. In another study of 148 PLWHA, HAART adherence was associated with age over 50 years (53% vs. 26%), but not alcohol use. The authors contend that older age groups have less substance use disorders overall and generally adhere better to medications. Absent from their discussion is that defining AUDs as “any use” of alcohol is perhaps a threshold too low to significantly impact adherence (Hinkin et al., 2004).

3.1.2 HAART Adherence in cross-sectional studies

Table 1 describes the 11 cross-sectional studies that were examined for the impact of AUDs on HAART adherence. Nine studies noted significantly decreased adherence in association with AUDs (Braithwaite et al., 2005; Chesney et al., 2000; Cook et al., 2001; Michel et al., 2010; Murphy et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2004; Parsons et al., 2007a; Parsons et al., 2007b; Peretti-Watel et al., 2006; Tucker et al., 2003). The differences in these studies pertained to how the AUD was defined (hazardous drinking, heavy drinking, binge drinking, or positive CAGE questionnaire screen) and the period of assessment (past day, past 3 days, past week, past 2 weeks, or past month).

Three studies measured alcohol use (regular use, any use, or use frequency) rather than abuse in their analyses (Murphy et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2004; Peretti-Watel et al., 2006). One study found ‘any alcohol use’ to be associated with past 3-day HAART adherence [OR=0.199, P < 0.05], but not with past week adherence (Murphy et al., 2002). On the other hand, another study reported an association between ‘increasing alcohol use’ and HAART adherence over the prior month [AOR=0.51 (0.33-0.79) at 95% CI] but not with past 3-day or past week adherence (Murphy et al., 2004). The inconsistency of these findings may be the vague definition of ‘alcohol use’, which did not necessarily relate to any marker of severity, chronicity or abuse.

A decade-old study compared adherent to non-adherent subjects and reported a significantly higher median consumption of alcoholic drinks in the past 30 days among non-adherent subjects despite only modest levels (9 drinks per month) of alcohol consumption in the overall sample (Chesney et al., 2000). In another study of 272 PLWHA on HAART meeting criteria for problem drinking using the AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test) an Alcohol Factor was created as a composite of problem drinking, negative consequences of drinking and total alcohol consumption. Increasing levels of AUDs, represented by the Alcohol Factor, were significantly associated with decreased adherence (Parsons et al., 2007b). Four additional cross-sectional studies also found AUDs (including heavy drinking, hazardous drinking, harmful alcohol consumption or binge drinking) to be associated with decreased adherence (Braithwaite et al., 2005; Cook et al., 2001; Michel et al., 2010; Tucker et al., 2003). These primarily used the past week as their sole assessment period for adherence; Cook et al 2001 also used past day measures (not significant) and Braithwaite et al 2005 only used past month adherence. A recent cross-sectional study also found a correlation between non-adherence and AUDs (alcohol abuse) among homeless PLWHA. These results, however, must be interpreted cautiously in light of the fact that adherence was measured over a narrow 2-day time-period (Friedman et al., 2009).

One cross-sectional study of HIV-infected men who have sex with men (MSM) failed to find an association between AUDs (hazardous drinking) and decreased adherence (Kleeberger et al., 2001). In this study, the 539 participants were followed for 15 years and, on average, attended 90% of their scheduled appointments over this time. The authors therefore suggest that this extraordinary adherence to clinical follow-up would then translate into adherence to their HIV medications.

3.1.3 HAART adherence in randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Two RCTs examined the effect of psychotherapeutic interventions on adherence in HIV-infected alcohol drinkers. In the first, 143 PLWHA with AUDs (hazardous drinkers) were randomized to either combined motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral therapy or standard educational sessions. Compared to controls, the intervention group experienced significantly higher increases in HAART adherence over 3 months. The intervention, however, failed to maintain adherence by 6 months, suggesting that it was not durable or the sample was insufficiently powered to detect small differences in adherence (Parsons et al., 2007a). In another RCT of 151 PLWHA with AUDs (hazardous drinkers) a multi-component psychotherapeutic intervention (composed of an educational/motivational session, a medications reminder and individualized counseling) was compared to standard of care. The differences in adherence between the two groups did not differ appreciably in either short (1-6 months) or long-term follow-up (12-13 months) (Samet et al., 2005).

3.2 The impact of alcohol use disorders on health care utilization

Eleven articles assessed the relationship between AUDs and health care utilization among PLWHA. In general, there was some disparity in the reported impact of alcohol use on health services utilization. See Table 2 for these parameters.

3.2.1 Impact of AUDs on outpatient visits

Seven articles examined the impact of AUDs on outpatient visits. Three of these studies found an association between AUDs and decreased utilization of outpatient services. A comparative study of two non-contemporaneous U.S. cohorts of PLWHA found that AUDs (heavy drinking) were significantly associated with fewer ambulatory visits among an underserved group targeted for supportive outreach, but not in a nationally representative group of PLWHA who were engaged in HIV care (Cunningham et al., 2006). Similarly, in a cross-sectional analysis of 349 PLWHAs with alcohol problems, AUDs (alcohol addiction severity) were significantly associated with fewer ambulatory visits (Kim et al., 2006). Among Veterans, similar results were found among 881 HIV-infected men with AUDs (hazardous drinking) (Gordon et al., 2006).

In contrast, two studies reported increased frequency of outpatient visits among PLWHA with AUDs compared to those without them. In one study, medical records of 16,048 HIV-infected veterans were followed prospectively for 12 months. Those with AUDs (alcohol problems) had significantly higher numbers of ambulatory visits overall but there was no association between AUDs and use of primary care or surgical clinics (Kraemer et al., 2006). The reason for this discrepancy in visit-type may have been that the majority of ambulatory visits by those with AUDs were for drug treatment or psychiatric care, rather than engagement in HIV treatment. Another study of 238 PLWHA found that AUDs (binge drinking) were associated with increased regular outpatient visits (Cunningham et al., 2006).

Finally, two studies did not find a significant association between AUDs and outpatient visits (Cunningham et al., 2007; Masson et al., 2004). The authors of both these articles speculated that heavy alcohol intake leads to an increase in acute care services (ED visits or hospitalizations) rather than use of more routine outpatient services. Future studies must carefully separate HIV primary care visits from more episodic care provided in EDs.

3.2.2 Impact of AUDs on hospitalizations

Three articles found a significant increase in frequency of hospitalizations among PLWHA with AUDs (hazardous drinking, alcohol dependence classified by ADS scale or ICD-9 coding) (Gordon et al., 2006; Kraemer et al., 2006; Palepu et al., 2005). Four other studies, however, found no such association (Cunningham et al., 2006; Josephs et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2006; Masson et al., 2004). In some of these studies, binge drinking was used as a measure of AUDs, which may have not appropriately captured the type of chronic alcohol abuse that might result in medical-related (rather than trauma) hospitalization (Cunningham et al., 2006; Josephs et al., 2010). Other inconsistencies may explain the lack of association found between AUDs and hospitalization. One study included only hospital admissions from the ED, thereby potentially overlooking direct admissions from the community or clinics (Josephs et al., 2010). Two other studies (Murphy et al., 2002; Murphy et al., 2004) risked sampling bias by studying populations that were disproportionately homeless and in which hospitalizations may have thus been driven by environmental factors or other co-morbid illnesses other than AUDs or HIV.

3.2.3 Impact of AUDs on Emergency Department (ED) visits

Seven studies assessed the impact of AUDs on ED visits. Of these, four found significant increases in frequency of ED visits among PLWHA with AUDs compared to PLWHAs without AUDs (Cunningham et al., 2007; Josephs et al., 2010; Kraemer et al., 2006; Masson et al., 2004). Three articles found no such association between ED utilization and AUDs (Cunningham et al., 2006; Gordon et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2006). Access to substance abuse treatment among PLWHAs in some of these studies may have led to less severe alcohol use and fewer ED visits. Furthermore, one paper did not measure ED visits to locations other than the Veterans Administration (VA) hospitals, which may have affected their results since most patients requiring emergency services live too far from VA services (Gordon et al., 2006).

3.2.4 Impact of AUDs on HAART utilization

Two papers reviewed assessed non-initiation of HAART despite clinical indication among PLWHA with AUDs. In a prospective cohort of 1171 PLWHA in Baltimore, those with AUDs (hazardous drinking) reported significantly decreased initiation of HAART over a 6-month period (Chander et al., 2006). A cross-sectional survey of 238 PLWHA arrived at similar conclusions whereby binge drinking was associated with decreased entry onto HAART (Cunningham et al., 2006).

3.2.5 Impact of AUDs on other measures of health care use

Health care utilization was broadened to include use of substance abuse and mental health treatment services. One paper found a significantly increased frequency of mental health care visits by HIV-infected veterans with AUDs compared to those without them (Kraemer et al., 2006). In another cross-sectional, multisite study of 803 PLWHA, subjects with AUDs (alcohol dependence) were significantly less likely to engage in drug treatment services (including outpatient clinics, self-help sessions or residential treatment programs). AUDs were not associated, however, with use of mental health services (Weaver et al., 2008) or receipt of PCP prophylaxis, and other quality of care indicators (Cunningham et al., 2006).

4. The impact of alcohol use disorders on health outcomes

Ten investigations (Table 3)4 assessed the impact of AUDs on biological HIV treatment outcomes, measured by CD4 counts (cells/mL) and HIV-1 RNA viral load (VL) (copies/mL). These measures are distal surrogates of accessing and properly utilizing HAART. The consequences of a non-suppressed VL are its association with HAART non-adherence, development of resultant drug-resistant viral mutations and accelerated progression of disease. Among PLWHA, the presence of AUDs was associated with increased VLs in five studies and decreased CD4 counts in four. A prospective study of HIV-infected veterans found that a detectable VL was more common among hazardous drinkers compared to non-hazardous drinkers (64.8% vs. 48.2%). There was no association found, however, between alcohol dependence, alcohol abuse or hazardous drinking and CD4 counts (Conigliaro et al., 2003). Another cross-sectional study of 349 PLWHAs with AUDs (hazardous drinking) found that among those on HAART (N=205), hazardous drinking was significantly associated with higher VL levels. Although there was a trend towards lower mean CD4 counts among those with AUDs, it did not achieve statistical significance (Samet et al., 2003). A Canadian study of HIV-infected drug injectors reported that any alcohol use in the previous 6 months was significantly associated with virologic non-suppression (Palepu et al., 2003). Another study used a more standard AUD definition (hazardous drinking) and similarly found it to be associated with virologic non-suppression (Chander et al., 2006). In a large prospective cohort, PLWHA with AUDs (severe drinking) had an increased likelihood of viral non-suppression and lower CD4 counts compared to moderate and light drinkers (Conen et al., 2009). Among a cohort of 2770 HIV-infected women, disparate associations between AUDs (hazardous drinking) and CD4 counts were reported; AUDs were significantly lower among women with 200-500 cells/mL, but not for those under 200 cells/mL (Cook et al., 2009). Though the authors speculate that those with higher CD4 counts felt well-enough to drink, but those with CD4>500 cells/mL did not differ from those with CD4<200. Alternatively, those with CD4<200 cells/mL might have been more likely to be on HAART given clinical guidelines for therapy. Similarly, in another longitudinal cohort which measured response to HAART over a period of 5 years, PLWHA with AUDs (hazardous drinking) had significantly decreased mean CD4 counts compared to those without AUDs among subjects not taking HAART; VL, however, did not differ over time (Samet et al., 2007). The discrepant findings between effect of AUDs on viral load and CD4 count may be explained by the dynamics of HIV infection, in which VL changes occur more rapidly than CD4 counts in response to HAART.

Table 3.

Impact of Alcohol Use Disorders on Health Outcomes: Study Characteristics

| Author, Publication year, Location | Study Design and Evaluation Period | Study Population, Sample Size | Measures of Health Outcomes and Time period of assessment | Alcohol Use Disorder Measure | Level of Health Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 count | HIV-1 RNA | |||||

| Chander, 2006, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1998-2003) | 1171 HIV+ persons in urban areas | Viral suppression defined as: HIV-1 RNA ≤400 copies/mL Previous 6 months |

Hazardous drinking defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion |

X | Decreased viral suppression with hazardous drinking AOR=0.76 (0.57-0.99) at 95% CI |

| Conen, 2009 Switzerland | Prospective Observational Cohort (2005-2007) | 4519 HIV+ persons on HAART | Detectable viral load defined as: HIV-1 RNA ≥ 400 copies/mL CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 Previous 6 months |

WHO International guide for alcohol consumption and related harm: Light, Moderate, Severe Drinking. | Increased likelihood of CD4 count <200/mm3 in severe drinkers compared to light drinkers AOR=0.81 (-0.30-2.02) at 95% Increased likelihood of CD4 count <200/mm3 in severe drinkers compared to moderate drinkers AOR=0.65(-0.80-2.11)at 95% CI |

Increased likelihood of detectable viral load in severe drinkers compared to light drinkers AOR= -0.10 (-0.32-0.12) at 95% CI Increased likelihood of detectable viral load in severe drinkers compared to moderate drinkers AOR= -0.17 (-0.44-0.09) at 95% CI |

| Conigliaro, 2003, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1999-2000) | 881 HIV+ veterans | Detectable viral load defined as: HIV-1 RNA > 500 copies/mL CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 Previous year |

Hazardous drinking defined as: Score ≧8 using AUDIT or having ≥6 drinks on one occasion in the past month (binge drinking) Alcohol abuse or dependence by ICD-9 |

CD4 count ≤200/mm3 not associated with hazardous drinking P=0.6 CD4 count ≤200/mm3 not associated with alcohol abuse or dependence P=0.9 |

Increased likelihood of detectable viral load in hazardous drinkers compared to non-hazardous drinkers (64.8% vs. 48.2%; P<0.001) Detectable viral load not associated with alcohol abuse or dependence P=0.6 |

| Cook, 2009, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1995-2006) | 2770 HIV+ women | CD4 count between 200-500 cells/mL CD4 count <200 cells/mL CD4 count >500 cells/mL Previous 6 months |

Hazardous drinking defined as: ≧7 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion |

Increased likelihood of CD4 counts between 200-500 cells/mL in hazardous drinkers AOR=1.10 (1.00-2.1) at 95% CI CD4 count <200 cells/mL and CD4 count >500 cells/mL not associated with hazardous drinking P>0.05 |

X |

| Henrich, 2008, U.S | Retrospective Cohort (2003-2004) | 239 HIV+ outpatients | Detectable viral load defined as: HIV-1 RNA > 500 copies/mL Mean CD4 count cells/mL change from baseline 18 months |

Alcohol Abuse defined using physician documented history of alcohol abuse | Mean change in CD4 count not associated with alcohol abuse P = 0.866 |

Detectable viral load not associated with alcohol abuse P = 0.629 |

| Palepu, Tyndall, 2003, Canada | Prospective Observational Cohort (1996-2001) | 234 HIV+ Injection drug users | Viral suppression defined as: Two consecutive HIV-1 RNA levels ≤ 500 copies/mL Previous 6 months |

Any self-reported alcohol use in prior 6 months | X | Decreased viral suppression with any alcohol use in prior 6 months AOR=0.31 (0.13-0.81) at 95% CI |

| Rosenbloom, 2007, U.S | Case Control cross sectional Study (2002-2005) | HIV+ men from HIV/AIDS and alcohol and substance abuse treatment centers HIV-Control (N=41) vs. HIV+ without alcohol dependence (N=44) vs. HIV- with Alcohol dependence (N=44) vs. HIV+ with Alcohol dependence (N=55) |

Log viral load (HIV-1 RNA copies/mL) change from baseline CD4 count cells/mL change from baseline Single time point |

Alcohol Dependence by SCID-IV | HIV+ with alcohol dependence not more likely to have decreased CD4 count P>0.05 | HIV+ with alcohol dependence not more likely to have increased log viral load P>0.05 |

| Samet, 2003, U.S | Cross Sectional Study (1997-2001) | 349 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems (205 on HAART) | Mean log10 HIV RNA copies/mL change from baseline Mean CD4 count cells/mL change from baseline Previous month |

Hazardous drinking (reported as At-risk drinking) defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks |

No association for subjects on HAART, P<0.07 (possible trend) No association for those not on HAART P>0.05 |

Increased log HIV RNA associated with hazardous drinking in subjects on HAART, P<0.006 No association for those not on HAART P>0.05 |

| Samet, 2005, U.S | Randomized Controlled Trial (1997-2000): Multi-component behavioral intervention vs. Standard care for HIV infection |

151 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems | Detectable viral load defined as: HIV-1 RNA > 500 copies/mL Mean Log HIV RNA copies/mL change from baseline Mean CD4 cell count, cells/mm3 change from baseline At baseline, 6 months and 12 months |

Hazardous drinking defined as: W: ≧7 drinks per week or 3 drinks per occasion M: ≧14 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion |

Change in mean CD4 count not associated with hazardous drinking P>0.25 | Detectable viral load not associated with hazardous drinking P>0.25 Change in mean log10 HIV RNA not associated with hazardous drinking P>0.25 |

| Samet, 2007, U.S | Prospective Observational Cohort (1997-2003) | 595 HIV+ persons with alcohol problems (354 on HAART) | Mean log10 HIV RNA copies/mL change from baseline Median CD4 count cells/mL change from baseline Previous 6 months |

Hazardous drinking (reported as heavy alcohol consumption) defined as: W+M above 66: ≧7 drinks per week or 4 drinks per occasion M below 66: ≧14 drinks per week or 5 drinks per occasion |

Decreased CD4 count associated with hazardous drinking in subjects not on HAART P =0.03 Change in CD4 count not associated with hazardous drinking in subjects on HAART P=0.9 |

Change in mean log10 HIV RNA not associated with hazardous drinking in subjects on HAART (P= 0.10) or off HAART (P=0.92) |

W=women, M=men

X: Not reported

AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio

ICD-9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

SCID-IV: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

Three studies found no association between AUDs and either CD4 count or VL. Among 239 PLWHA, VL and CD4 counts did not differ among those with AUDs versus those who did not (Henrich et al., 2008). This may, in part, be explained by the use of non-validated criteria for alcohol abuse: >3 drinks/day for 10 years and a history of driving while intoxicated. In a case-control study comparing PLWHAs with and without AUDs (alcohol dependence), mean CD4 counts and VLs were not significantly different. Subjects with CD4<100 cells/mL and those with medical disabilities, however, were excluded from the study, possibly attenuating any existing associations (Rosenbloom et al., 2007). Among HIV-infected problem drinkers enrolled in a randomized control trial comparing a multi-component intervention versus standard care, no significant differences in CD4 and VL were detected overall or between the intervention and control groups (Samet et al., 2005).

4. Discussion

AUDs and HIV are prevalent and each independently contribute negatively to poor health outcomes. When combined, there appears to be synergistic negative consequences that result in increased morbidity and mortality. The literature on the interface of these two fields is staggering and is complicated further by the added contribution of co-morbid mental illness, which is highly prevalent among both groups. The findings from existing studies vary based upon the population being studied, study design, and measurements used to define AUDs, HAART adherence and types of HIV treatment outcomes. In this systematic review, we comprehensively assembled and clarified these definitions to determine the impact of AUDs on adherence to antiretroviral therapy (N=20), health care utilization (N=11) and HIV treatment outcomes (N=10). In general, and with some notable exceptions, AUDs negatively impact adherence to antiretroviral therapy, health care utilization and HIV treatment outcomes.

The reviewed studies included longitudinal, cross-sectional, case-control studies and randomized controlled trials to examine the impact of AUDs on HAART adherence, health care utilization patterns and HIV treatment outcomes. Most studies confirm that the presence of AUDs, particularly with increasing levels of severity, significantly decreases HAART adherence. Challenging within these studies are the ways in which adherence was assessed (self-reports vs. MEMS caps vs. pill counts) and the thresholds that qualified as suboptimal adherence. The simplicity of new antiretroviral regimens and varying thresholds required to sustain virologic suppression among differing antiretroviral medication classes now begs the question: is it really adherence (the intermediary outcome) or viral suppression itself that we should aim to measure and achieve in practice (Bangsberg, 2006; Parienti et al., 2009)? Thus, even among PLWHA who have AUDs, interventions that statistically improve adherence by even 10-20% would not lead to clinically relevant virological outcomes, evidenced by the availability of contemporary regimens that include NNRTIs and newer boosted protease inhibitors with long half lives (Parienti et al., 2010); the latter are also impressively resistant to development of resistance even in the setting of poor adherence (Tarn et al., 2008).

Health care utilization, like adherence, is a crucial element of HIV treatment success. Routine and regular care is needed to monitor CD4 counts, viral loads, resistance testing, and screening for opportunistic diseases and side effects among other necessities of treatment. Decreased health care use appears to be common among PLWHA with co-morbid AUDs because of alcohol's disruptive effects on cognition, judgment and lifestyle. AUDs have also been associated with increased episodic health care use, like ED use, because of increased morbidity associated with heavy drinking itself. By stratifying by these differing types of health care use, we were able to aggregate these negative health care utilization consequences among PLWHA and AUDs. Prospective studies using an array of AUD measurements to examine health services utilization patterns merit further investigation. From a clinical perspective, interventions that markedly decrease alcohol consumption are likely to have the greatest enhancement on HIV treatment outcomes. Though pharmacological interventions like depot naltrexone demonstrate modest improvements in alcohol treatment outcomes, they have been confirmed to be superior to non-pharmacological interventions (Anton et al., 2006), and may be one approach to effectively engage patients in life-saving treatment. Pharmacological treatments have not, however, been tested in HIV-infected populations. Alternatively, the co-location or integration of services where both HIV and alcohol treatment are treated simultaneously in one setting (Sylla et al., 2007), may be another effective strategy to engage patients and improve outcomes. In either scenario, it is critical to create interventions that are efficacious, safe and cost-effective.

AUDs are commonly associated with poor CD4 and VL outcomes. While our review specifically examined these two treatment outcomes, other health outcomes are also negatively impacted by AUDs. Indeed, neuro-cognitive decline (Green et al., 2004), depression (Sullivan et al., 2008), lipodystrophy (Cheng et al., 2009), and accelerated progression to end-stage liver disease among HIV/HCV co-infected patients (Cheng et al., 2007) have all also been associated with AUDs among PLWHA.

There are several limitations to this review. While an extensive search of the literature deployed multiple databases and search engines, there is no guarantee that all relevant articles were found. Variations in definitions of AUDs, adherence and health care use made between-study comparison more difficult to interpret. While selected studies included most regions of the world, the vast majority was from the U.S., limiting generalizability. This is relevant in that some regions of the world, like Eastern Europe and Africa, have staggering rates of AUDs plus some of the most explosive HIV epidemics – potentially a perfect storm for devastating consequences. Last, most studies did not disentangle whether an underlying mental illness complicated care and worsened outcomes. Further studies will need to assess the impact of depression and other mental illness on HIV treatment outcomes.

This systematic review is, to our knowledge, the first to examine the impact of AUDs (defined broadly) on health care utilization and HIV treatment outcome measures in this population. A meta-analysis of alcohol use and HAART adherence precedes our own and reports an overall significant association between alcohol use and non-adherence (Hendershot et al., 2009); this review did not examine the multiple operational definitions we use here. With the mounting number of studies on the topic of AUDs and HIV outlined by this systematic review, it is now clearly the time to move from assessment to intervention. Interventions may target the individual; the clinical care setting; or address structural barriers. They can be grounded in behavioral modification theory or include pharmacological agents such as naltrexone that is approved for the treatment of alcohol use disorders, but has not yet been empirically tested in PLWHAs (Anton et al., 2006).

It is clear that PLWHAs must first be diagnosed in order to enter into life-saving or life-prolonging care. Though PLWHAs with AUDs present late to care (Samet et al., 1998), once identified, it is essential to increase access and retention in care and to HAART. Once prescribed HAART, interventions should have four primary goals: 1) retention on HAART (persistence); 2) high HAART adherence levels; 3) to maximize CD4 counts and suppress VL; and 4) to decrease HIV risk-taking behaviors. If interventions are able to maximize viral suppression, they are likely to result in decreased HIV transmission to others even if HIV risk behaviors are not reduced (Granich et al., 2009).

Most individual or group-based interventions target cognition and adherence to medications alone. They may not, however, be sufficient to address other behavioral factors, such as alcohol and drug use, which negatively impact both cognitive function as well as adherence (Anand et al., 2010). Indeed, improved adherence is associated with recent abstinence from alcohol, suggesting the need to markedly reduce alcohol use, perhaps with pharmacological therapies (Samet et al., 2004). Alcohol-induced impairment has an immediate effect on cognitive functioning that may impede self-efficacy and behaviors, including adherence to prescribed longitudinal care. For example, PLWHAs have been demonstrated to feel less confident about taking their HIV prescribed medications (Parsons et al., 2004) or attending medical appointments when intoxicated (Meier et al., 2006; Palmer et al., 2009). Addressing such issues are unclear but need addressing by future research. Regardless of the program components, it is clear that effectively treating AUDs among PLWHA will likely improve outcomes for the individual and society.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Additional background materials and data available with the online version of this article at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx …

The electronic appendix is available with the online version of this article at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx …

A more detailed version of Table 1 is available with the online version of this article at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx …

A more detailed version of Table 2 is available with the online version of this article at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx …

A more detailed version of Table 3 is available with the online version of this article at doi:xxx/j.drugalcdep.xxx …

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anand P, Springer SA, Copenhaver MM, Altice FL. Neurocognitive Impairment and HIV Risk Factors: A Reciprocal Relationship. AIDS Behav. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9684-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O'Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, Gastfriend DR, Hosking JD, Johnson BA, LoCastro JS, Longabaugh R, Mason BJ, Mattson ME, Miller WR, Pettinati HM, Randall CL, Swift R, Weiss RD, Williams LD, Zweben A, COMBINE Study Research Group Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balla AK, Lischner HW, Pomerantz RJ, Bagasra O. Human studies on alcohol and susceptibility to HIV infection. Alcohol. 1994;11:99–103. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006:939–941. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, Roberts MS, Shechter S, Schaefer A, McGinnis K, Rodriguez MC, Rabeneck L, Bryant K, Justice AC. Estimating the impact of alcohol consumption on survival for HIV+ individuals. AIDS Care. 2007;19:459–466. doi: 10.1080/09540120601095734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, Maisto SA, Crystal S, Day N, Cook RL, Gordon A, Bridges MW, Seiler JF, Justice AC. A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171937.87731.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chander G, Lau B, Moore RD. Hazardous alcohol use: a risk factor for non-adherence and lack of suppression in HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:411–417. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243121.44659.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng DM, Libman H, Bridden C, Saitz R, Samet JH. Alcohol consumption and lipodystrophy in HIV-infected adults with alcohol problems. Alcohol. 2009;43:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng DM, Nunes D, Libman H, Vidaver J, Alperen JK, Saitz R, Samet JH. Impact of hepatitis C on HIV progression in adults with alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:829–836. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, Wu AW. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conen A, Fehr J, Glass TR, Furrer H, Weber R, Vernazza P, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Bucher HC, et al. Self-reported alcohol consumption and its association with adherence and outcome of antiretroviral therapy in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antiviral Therapy. 2009;14:349–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conigliaro J, Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, Rabeneck L, Justice AC, Veterans Aging Cohort 3-Site Study How harmful is hazardous alcohol use and abuse in HIV infection: do health care providers know who is at risk? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;33:521–525. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200308010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Sereika SM, Hunt SC, Woodward WC, Erlen JA, Conigliaro J. Problem drinking and medication adherence among persons with HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Zhu F, Belnap BH, Weber K, Cook JA, Vlahov D, Wilson TE, Hessol NA, Plankey M, Howard AA, Cole SR, Sharp GB, Richardson JL, Cohen MH. Longitudinal trends in hazardous alcohol consumption among women with human immunodeficiency virus infection, 1995-2006. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1025–1032. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Wong MD, Relf M, Cunningham WE, Drainoni ML, Bradford J, Pounds MB, Cabral HD. Utilization of health care services in hard-to-reach marginalized HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:177–186. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham WE, Sohler NL, Tobias C, Drainoni Ml, Bradford J, Davis C, Cabral HJ, Cunningham CO, Eldred L, Wong MD. Health services utilization for people with HIV infection: comparison of a population targeted for outreach with the U.S. population in care. Med Care. 2006;44:1038–1047. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000242942.17968.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JC, Bang H, Kapiga SH. The association between HIV infection and alcohol use: a systematic review and meta-analysis of African studies. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:856–863. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318067b4fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, Kidder DP, Henny KD, Courtenay-Quirk C, Aidala A, Royal S, Holtgrave DR, START, S.G.P. Associations between substance use, sexual risk taking and HIV treatment adherence among homeless people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21:692–700. doi: 10.1080/09540120802513709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, London AS, Caetano R, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Morton SC, Orlando M, Shapiro M. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:179–186. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golin CE, Liu H, Hays RD, Miller LG, Beck CK, Ickovics J, Kaplan AH, Wenger NS. A prospective study of predictors of adherence to combination antiretroviral medication. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:756–765. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.11214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AJ, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Rabeneck L, Justice AC, VACS-3 Project Team Associations between alcohol use and homelessness with healthcare utilization among human immunodeficiency virus-infected veterans. Med Care. 2006;44:S37–43. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223705.00175.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JE, Saveanu RV, Bornstein RA. The effect of previous alcohol abuse on cognitive function in HIV infection. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:249–254. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. A 10-year national trend study of alcohol consumption, 1984-1995: is the period of declining drinking over? Am J Public Health. 2000;90:47–52. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol Use and Antiretroviral Adherence: Review and Meta-Analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich TJ, Lauder N, Desai MM, Sofair AN. Association of alcohol abuse and injection drug use with immunologic and virologic responses to HAART in HIV-positive patients from urban community health clinics. J Community Health. 2008;33:69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin C, Hardy D, Mason K, Castellon S, Durvasula R, Lam M, Stefaniak M. Medication adherence in HIV-infected adults: effect of patient age, cognitive status, and substance abuse. AIDS. 2004;18:S19–S25. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200418001-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaki L, Kresina TF. Directions for biomedical research in alcohol and HIV: where are we now and where can we go? AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:1197–1207. doi: 10.1089/08892220050116961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs JS, Fleishman JA, Korthuis PT, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Emergency department utilization among HIV-infected patients in a multisite multistate study. HIV Med. 2010;11:74–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justus AN, Finn PR, Steinmetz JE. The influence of traits of disinhibition on the association between alcohol use and risky sexual behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1028–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8:141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW, Kertesz SG, Horton NJ, Tibbetts N, Samet JH. Episodic homelessness and health care utilization in a prospective cohort of HIV-infected persons with alcohol problems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeberger CA, Phair JP, Strathdee SA, Detels R, Kingsley L, Jacobson LP. Determinants of heterogeneous adherence to HIV-antiretroviral therapies in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;26:82–92. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200101010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer K, McGinnis K, Skanderson M, Cook R, Gordon A, Conigliaro J, Shen Y, Fiellin D, Justice A. Alcohol problems and health care services use in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and HIV-uninfected veterans. Med Care. 2006;44:S44–S51. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000223703.91275.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefevre F, O'Leary B, Moran M, Mossar M, Yarnold PR, Martin GJ, Glassroth J. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:458–460. doi: 10.1007/BF02599920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson CL, Sorensen JL, Phibbs CS, Okin RL. Predictors of medical service utilization among individuals with co-occurring HIV infection and substance abuse disorders. AIDS Care. 2004;16:744–755. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331269585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier PS, Donmall MC, McElduff P, Barrowclough C, Heller RF. The role of the early therapeutic alliance in predicting drug treatment dropout. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;83:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel L, Carrieri MP, Fugon P. Harmful alcohol consumption and patterns of substance use in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretrovirals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study): Relevance for clinical management and intervention. Care, A. 2010 doi: 10.1080/09540121003605039. Ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Greenwell L, Hoffman D. Factors associated with antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected women with children. Women Health. 2002;36:97–111. doi: 10.1300/J013v36n01_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Marelich WD, Hoffman D, Steers WN. Predictors of antiretroviral adherence. AIDS Care. 2004;16:471–484. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol alert #57. [November 10 2009];2002 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa57/htm.

- Palepu A, Horton NJ, Tibbetts N, Meli S, Samet JH. Substance abuse treatment and hospitalization among a cohort of HIV-infected individuals with alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:389–394. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000156101.84780.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Li K, Yip B, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, Montaner JSG, Hogg RS. Alcohol use and incarceration adversely affect HIV-1 RNA suppression among injection drug users starting antiretroviral therapy. J Urban Health. 2003;80:667–675. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, Murphy MK, Piselli A, Ball SA. Substance user treatment dropout from client and clinician perspectives: a pilot study. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:1021–1038. doi: 10.1080/10826080802495237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parienti JJ, Bangsberg DR, Verdon R, Gardner EM. Better adherence with once-daily antiretroviral regimens: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:484–488. doi: 10.1086/596482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parienti JJ, Peytavin G, Reliquet V, Verdon R, Coquerel A. Pharmacokinetics of the treatment switch from efavirenz to nevirapine. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1547–1548. doi: 10.1086/652718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Golub SA, Rosof E, Holder C. Motivational interviewing and cognitive-behavioral intervention to improve HIV medication adherence among hazardous drinkers: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007a;46:443–450. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318158a461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rosof E, Mustanski B. Patient-related factors predicting HIV medication adherence among men and women with alcohol problems. J Health Psychol. 2007b;12:357–370. doi: 10.1177/1359105307074298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Vicioso KJ, Punzalan JC, Halkitis PN, Kutnick A, Velasquez MM. The impact of alcohol use on the sexual scripts of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Sex Res. 2004;41:160–172. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretti-Watel P, Spire B, Lert F, Obadia Y. Drug use patterns and adherence to treatment among HIV-positive patients: evidence from a large sample of French outpatients (ANRS-EN12-VESPA 2003) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:S71–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(06)80012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Alcohol use in HIV patients: what we don't know may hurt us. Int J STD AIDS. 1999;10:561–570. doi: 10.1258/0956462991914654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RachBeisel J, Scott J, Dixon L. Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: A review of recent research. Psychiat Serv. 1999;50:1427–1434. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.11.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom MJ, Sullivan EV, Sassoon SA, O'Reilly A, Fama R, Kemper CA, Deresinski S, Pfefferbaum A. Alcoholism, HIV infection, and their comorbidity: factors affecting self-rated health-related quality of life. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:115–125. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Cheng DM, Libman H, Nunes DP, Alperen JK, Saitz R. Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2007;46:194. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318142aabb. 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Stein MD, Lewis R, Savetsky J, Sullivan L, Levenson SM, Hingson R. Trillion virion delay: time from testing positive for HIV to presentation for primary care. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:734–740. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.7.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, Dukes K, Tripps T, Sullivan L, Freedberg KA. A randomized controlled trial to enhance antiretroviral therapy adherence in patients with a history of alcohol problems. Antivir Ther. 2005;10:83–93. doi: 10.1177/135965350501000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Horton NJ, Meli S, Freedberg KA, Palepu A. Alcohol consumption and antiretroviral adherence among HIV-infected persons with alcohol problems. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:572–577. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000122103.74491.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samet JH, Horton NJ, Traphagen ET, Lyon SM, Freedberg KA. Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression: are they related? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:862–867. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065438.80967.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Irving H, Rehm J. Alcohol as a correlate of unprotected sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS: review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2009a;13:1021–1036. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuper PA, Joharchi N, Irving H, Rehm J. Alcohol as a Correlate of Unprotected Sexual Behavior Among People Living with HIV/AIDS: Review and Meta-Analysis. AIDS Behav. 2009b doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan L, Saitz R, Cheng D, Libman H, Nunes D, Samet J. The impact of alcohol use on depressive symptoms in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Addiction. 2008;103:1461–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sylla L, Bruce RD, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Integration and co-location of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and drug treatment services. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarn LW, Chui CK, Brumme CJ, Bangsberg DR, Montaner JS, Hogg RS, Harrigan PR. The relationship between resistance and adherence in drug-naive individuals initiating HAART is specific to individual drug classes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:266–271. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318189a753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Substance use and mental health correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral medications in a sample of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Med. 2003;114:573–580. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Orlando M, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Psychosocial mediators of antiretroviral nonadherence in HIV-positive adults with substance use and mental health problems. Health Psychol. 2004;23:363–370. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]