Abstract

Progression of degeneration is often described in patients with initially degenerated segment adjacent to fusion (iASD) at the time of surgery. The aim of the present study was to compare dynamic fixation of a clinically asymptomatic iASD, with circumferential lumbar fusion alone. 60 patients with symptomatic degeneration of L5/S1 or L4/L5 (Modic ≥ 2°) and asymptomatic iASD (Modic = 1°, confirmed by discography) were divided into two groups. 30 patients were treated with circumferential single-level fusion (SLF). In dynamic fixation transition (DFT) patients, additional posterior dynamic fixation of iASD was performed. Preoperatively, at 12 months, and at a mean follow-up of 76.4 (60–91) months, radiological (MRI, X-ray) and clinical (ODI, VAS, satisfaction) evaluations assessed fusion, progression of adjacent segment degeneration (PASD), radiologically adverse events, functional outcome, and pain. At final follow-up, two non-fusions were observed in both groups. 6 SLF patients and 1 DFT patient presented a PASD. In two DFT patients, a PASD occurred in the segment superior to the dynamic fixation, and in one DFT patient, a fusion of the dynamically fixated segment was observed. 4 DFT patients presented radiological implant failure. While no differences in clinical scores were observed between groups, improvement from pre-operative conditions was significant (all p < 0.001). Clinical scores were equal in patients with PASD and/or radiologically adverse events. We do not recommend dynamically fixating the adjacent segment in patients with clinically asymptomatic iASD. The lower number of PASD with dynamic fixation was accompanied by a high number of implant failures and a shift of PASD to the superior segment.

Keywords: Adjacent segment degeneration, Dynamic stabilization, Hybrid fixation, Lumbar circumferential fusion, Low back pain, Clinical study

Introduction

Many studies report a clinically relevant and accelerated progression of degeneration in the vertebral disc adjacent to a fused level, resulting in a poorer clinical outcome and a need for re-operation [4, 16, 26, 29].

Despite many other proposed reasons for adjacent segment degeneration, such as genetic predisposition, an increase in the range of motion was observed in the adjacent segment after circumferential fusion, potentially leading to overstress [11, 13, 17, 25]. Especially postoperatively sagittally unbalanced patients seem to be at risk of adjacent segment degeneration because of their need for compensation of the imbalance in these segments [18, 23]. Furthermore, adjacent disc degeneration was more frequently described when initial degeneration of the adjacent segment was present at the time of fusion surgery [7, 24]. In such cases, the spinal surgeon must decide either to accept the risk of adjacent level degeneration by operating only one level, or to fuse both levels—with the risk of simply shifting the problem one level superiorly—by treating an only initially degenerated disc.

To address the general problems of progression of degeneration in an adjacent and/or initially degenerated disc, dynamic stabilization systems have been developed. The Dynesys® implant is one of the longest-known and -applied dynamic implants, which preserves but limits motion, while reducing facet joint loads and disc pressure in the treated segment in extension [14, 30, 35]. It has been shown to reduce adjacent segment degeneration clinically [27].

A dynamic stabilization of an initially degenerated disc adjacent to a circumferential fusion may be able to reduce a further progression of degeneration at this level [3, 33, 35]. Moreover, compared with a two-level-fusion, an overstress of the disc superior to dynamic stabilization can potentially be avoided.

The aim of the current study was to research the differences in clinical and radiological outcomes between mono-segmental circumferential lumbar fusion alone and dynamic fixation adjacent to circumferential fusion—employing the Allospine™ Dynesys® Transition System (Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland)—in patients with clinically asymptomatic but radiologically proven initial disc degeneration adjacent to the fusion level. The hypotheses were a reduced progression of adjacent disc degeneration and, resulting from this, a better clinical outcome in the group of Allospine™ Dynesys® Transition treated patients.

Materials and methods

The conduct of this study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee under ruling No. P1303. Every patient signed an informed consent on the treatment performed in this study.

Study design

Patients, who presented persistent lumbosacral and/or non-radicular complaints after an unsuccessful conservative therapy, covering a period of at least 6 months, were enrolled in this prospective, randomized, non-blind study.

At the same time, osteochondrosis in Modic grade ≥ 2, resulting from idiopathic intervertebral disc degeneration of segments L4/5 or L5/S1, and idiopathic disc degeneration of Modic grade = 1 at the superior adjacent level, had to be detectable in MRI [20]. The presence of an isthmic spondylolisthesis, up to grade II according to Meyerding, in the inferior level (fusion level) as well as facet joint arthritis of Fujiwara grade = 1 at the adjacent level, did not lead to exclusion [9].

Patients were excluded from the study if degeneration of the adjacent segment was symptomatic, as reflected by a positive memory pain in discography and/or positive disc analgesia. When found in MRI, degeneration of segments superior to the adjacent segment also led to exclusion.

Further exclusion criteria consisted of additional degenerative findings, such as severe facet joint arthritis—Fujiwara > grade 1—spondylolisthesis, or radiological signs of instability (traction spurs, segmental translation > 4 mm, segmental range of motion in extension-flexion radiographs >10°) [6, 19] in any segments superior or inferior to fusion; spinal deformities, or destructive processes; previous operations on the lumbar spine; patients on long-term medication with corticoids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), with chronic pain ≥ grade II according to Gerbershagen et al. [10]; patients with osteoporosis, kidney or liver diseases, malignant tumors, or a BMI > 30 kg/m²; pregnancy; and chronic nicotine, alcohol, or drug abuse.

Patients and groups

A power analysis was conducted to estimate the necessary group size for expected differences in the clinical test parameters between the groups (β = 0.20, α = 0.05). A clinically relevant difference of ten points was chosen. The standard deviation was set to 13, based on about 100 patients from previous studies of our group. Group sizes were set to 30 each.

Sixty patients (31 men, 29 women) were included in this study between January 2000 and May 2002. Patients were randomly allocated to two groups. Epidemiological data of the patients and groups can be found in Table 1. Randomization was performed by the Randlist Software (DataInf GmbH, Tuebingen, Germany).

Table 1.

Demographic patient and intraoperative data

| Variable | SLF group | DFT group |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (for analysisa) | 30 (25) | 30 (22) |

| Age (years) (min–max) | 44.6 (27–63) | 44.9 (27–62) |

| Gender (male/female) | 14/16 | 17/13 |

| Mean body weight (kg) | 81.4 (51–101) | 80.9 (53–103) |

| Level of fusion surgery (L4/5/L5/S1) | 6/24 | 7/23 |

| Mean blood loss (ml) | 457.2 | 467.1 |

| Mean OP-duration (min) | 126.4 | 139.7 |

| Mean hospitalization (days) | 7 | 7 |

a13 patients were lost during follow-up and were excluded

The 30 patients of the control group, single level fusion (SLF), were surgically treated with an anterior–posterior fusion, whereas the 30 patients of the study group, dynamic fixation transition (DFT), received an additional dynamic fixation of the superior segment adjacent to fusion.

Surgical procedure and implant design

In all cases of both groups, anterior-posterior spondylodesis was conducted in a single session. Each surgery session involved an initial anterior approach, followed by posterior stabilization. After cleaning out the intervertebral disc and removing the cartilaginous endplate via a pararectal, retroperitoneal approach, two titanium cages (Surgical Titanium Mesh, DePuy Spine, Kirkel, Germany) with individually adapted height and of 16 mm diameter were inserted into the intervertebral space. Cages were filled with a standardized block of freeze-dried allogenic cancellous bone, which had been cut to the shape of the cage interior before sterilization. No further material was inserted around the cages in either group.

Posterior spondylodesis was conducted using a monoaxial angle-stabilizing screw and rod system (Allospine™, Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland). Autogenous cortico-cancellous material, obtained through the decortication of the facet joints and laminae in the fusion area, was placed posterolaterally between the laminae and the facet joints, at the level to be fused in each case.

Additionally, in the DFT group, two Dynesys® pedicle screws (Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) were placed into the adjacent vertebra, preserving the adjacent segment’s facet joints. A connecting device (Allospine™ Transition, Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) served as a junction between the superior, rod-connected pedicle screws between the fusion segment and the dynamic fixation device (Fig. 1). The cylindrical spacers, made of polycarbonate-urethane, were positioned on both sides, between the adjacent segment screw heads and the connecting device. Stabilizing cords, consisting of polyethylene terephthalate and forming the core of the spacers, were fixed under tension using the adjustment screws in the heads of the pedicle screws and in the connecting device.

Fig. 1.

The Allospine™ Dynesys® Transition device (Zimmer, Winterthur, Switzerland) implanted to a spine model. A connector links the rigid to the dynamic fixation

Every patient was operated on by the same surgeon. Each of the patients was then mobilized without an orthosis and given physiotherapy from the first postoperative day onwards.

Data collection

Each of the patients was given clinical and radiographic examinations: preoperatively, postoperatively, and then 12 months subsequently. Long-term follow-up was performed after at least 60 months postoperatively. MRI diagnostics were performed preoperatively, at 12 months, and at long-term follow-up.

During the perioperative period, the mean duration of surgery, intraoperative blood loss, and the length of the patients’ hospital stay were all recorded. Complications ascertained both during and after the operation were monitored up until final follow-up. Patients who failed to attend one or more follow-up examinations were excluded from statistical analysis.

Clinical follow-up

The Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire Version 2.0 (ODI), according to Fairbank et al. [8], was used to assess subjective functional impairment. In addition, pain severity was estimated by using a visual analog scale (VAS), with a scale graduation of 0–100 mm (0 mm, minimal pain; 100 mm, maximal pain). During the follow-up appointments, the patients were additionally asked about their degree of satisfaction with the operation.

Radiological follow-up

The qualitative radiographic evaluation of fusion was based on the criteria for vertebral body fusion using intersomatic cages employing both plain and extension-flexion radiographs [28].

At 12 months and long-term follow-up, evaluation of the progression of degeneration in the two segments adjacent to the fused one was based on MRI changes in Modic and Fujiwara scores, and on radiographic measurement of disc height compared with the preoperative status [5]. Additionally, plain and extension-flexion radiographs were used to evaluate the adjacent segments for fusion (based on the criteria described above) or radiographic signs of instability [6, 19]. To conclude, a progression of degeneration in the adjacent segments required at least one of the following criteria to be fulfilled:

Fusion

Disc degeneration, Modic > grade 1

Facet joint arthritis, Fujiwara > grade 1

≤25% of the preoperative disk height

Radiographic signs of instability (traction spurs, etc.).

The radiographs were evaluated independently and blinded, by both a radiologist specializing in spinal imaging and an orthopedic surgeon. A second independent orthopedic surgeon was used to adjudicate on conflicting fusion findings.

When presenting radiologically adverse events, such as screw-loosening, screw or rod failure, implant dislocation, radiological non-union of the fusion segment, or signs of progression of degeneration in the adjacent segments at final follow-up, patients were allocated to a sub-group, which was compared with the radiologically asymptomatic sub-group of patients with the same instrumentation, with respect to their clinical outcome parameters.

Statistical analysis

The data from this study were analyzed using the SPSS 17.0 statistics software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA). Power analysis was performed employing NCSS 2004–PASS 2005 Software (Kaysville, USA). VAS and ODI were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA for repeated measures with post hoc Bonferroni testing. Categorical variables were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test, or with a χ² test. The inter-observer variability was tested using κ-statistics. The significance level for all the statistical tests was p = 0.05.

Results

The mean long-term follow-up was 76.4 months (60–91 months). Five patients (5/30) from the SLF group and eight patients (8/30) from the DFT group failed to attend every follow-up and were therefore excluded. Up until the time of exclusion from the study, the follow-up had been free from complications in any of these patients.

Peri-operative data

Group-specific levels of instrumentation, blood loss, hospital stay, and operation time are shown in Table 1. The mean duration of surgery was significantly higher in the DFT group (p < 0.001). The mean surgery-related blood loss and the average length of the patients’ hospital stay were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1). No infection was apparent during follow-up. In one patient of each group, intra-operative bleeding from V. iliaca communis had to be stopped by suture.

Follow-up examinations

Radiological results

Evaluation of fusion at the level where spondylodesis was performed revealed that three patients per group presented a clinically asymptomatic radiological non-fusion at 12 months (p = 1.000 between the groups, κ = 0.89). At final follow-up, two asymptomatic non-unions per group were radiologically observed (p = 1.000 between the groups κ = 0.87).

Progression of degeneration in the adjacent segment was visible in six SLF patients (Fig. 2), whereas in the DFT group, a progression of degeneration in the dynamically stabilized segment was registered in one patient, who presented increasing instability. Two patients developed a progression of degeneration in the segment adjacent to the dynamic stabilization (Fig. 3). One additional DFT patient presented a fusion of the dynamically stabilized segment. No statistical difference could be observed between the groups regarding the number of patients with progression of degeneration in all segments superior to fusion (p = 0.260). This degeneration progress led to re-operation (PLIF at adjacent segment) in only one patient of group SLF, who presented symptomatic adjacent segment degeneration with claudication and back and leg pain at final follow-up. All other patients radiologically presenting progression of degeneration in adjacent segments were not re-operated, since radiological findings were clinically asymptomatic.

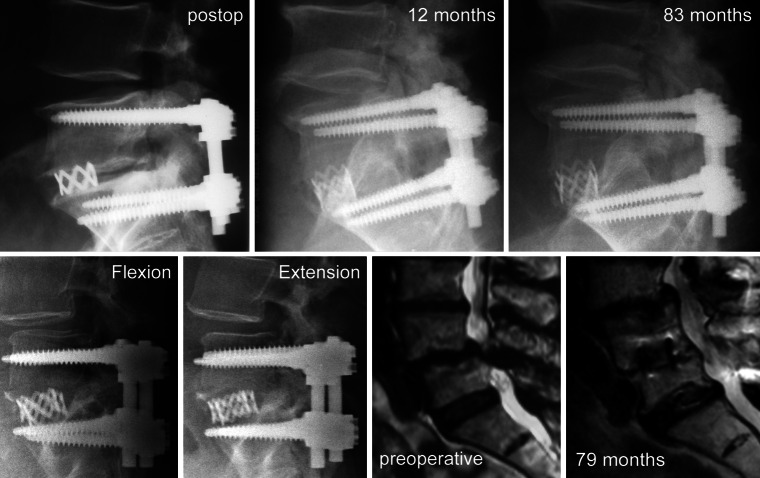

Fig. 2.

Three examples of progression of adjacent segment degeneration in the SLF group representing extreme cases regarding discrepancy between clinical and radiological pictures. Upper row (from left to right) plain radiographs of a patient with increasing osteochondrosis over time. Lower row flexion–extension radiographs (left) of a patient with instability of the adjacent segment at final follow-up. Preoperative MRI and MRI at final follow-up (right) of another patient

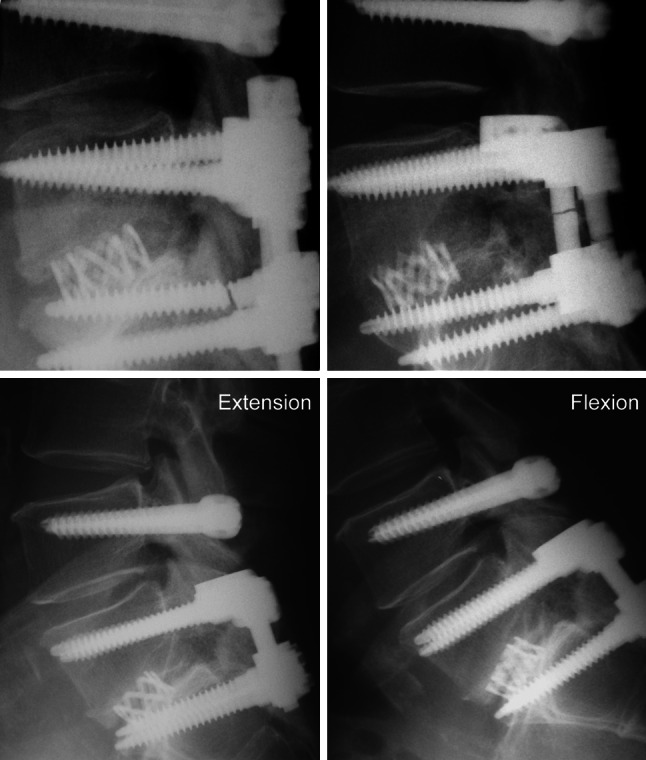

Fig. 3.

Three examples of radiologically adverse events in the DFT group. Upper row Patients with implant failure (left) at S1-screw left and (right) at rods at both sides despite successful fusion. Lower row extension–flexion radiographs of a patient with instability in the segment superior to dynamic fixation 7 years after surgery

No implant-associated adverse events were observed in the SLF group during follow-up. At final follow-up, one DFT patient presented a failure of the implant rods at both sides (fusion level) and in two patients, the left S1-screw (fusion level) broke (Fig. 3). All three patients with implant failure at the fusion level were clinically asymptomatic and segments were successfully fused despite the radiological findings. Two other patients of the DFT group presented a temporary, clinically asymptomatic radiolucent line around the Dynesys® screws, which were also clinically asymptomatic. Radiolucent lines could not be observed at final follow-up. Another DFT patient needed revision surgery after 26 months because of a clinically symptomatic dislocation of the Dynesys® screws. This patient was excluded from further analysis because dynamic stabilization was removed during revision surgery. All radiologically observed adverse events are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Radiologically apparent adverse events at final follow-up

| Type of event | Number of patients SLF group (n = 25) | DFT group (n = 22 – 1a) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-union (fusion segment) | 2 | 2 |

| Progression of degeneration adjacent to fusion | 6 | 1 |

| Progression of degeneration superior to the adjacent segment | – | 2 |

| Fusion at adjacent segment | – | 1 |

| Screw breakage at fusion segment | 0 | 2 |

| Rod breakage at fusion segment | 0 | 1 |

| Total (radiologically symptomatic subgroup) | 8 | 9 |

aOne patient with implant loosening was surgically revised and excluded from statistical evaluation

Clinical results

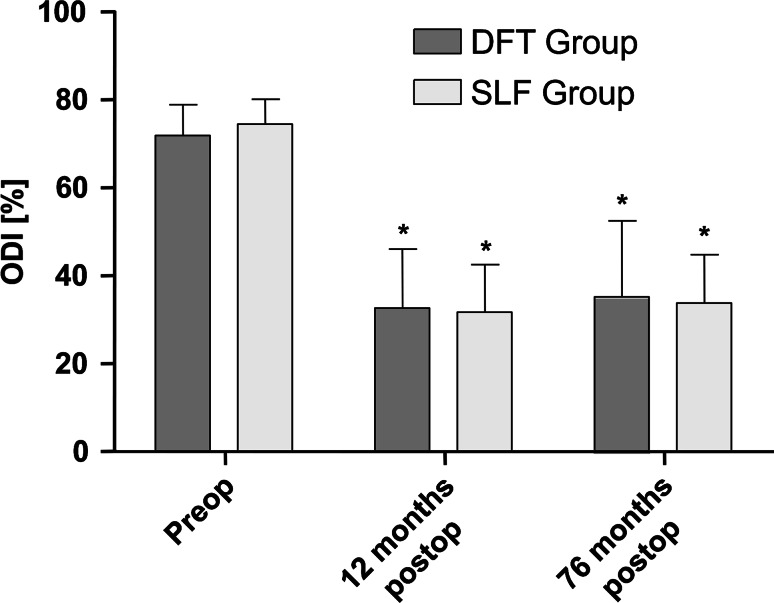

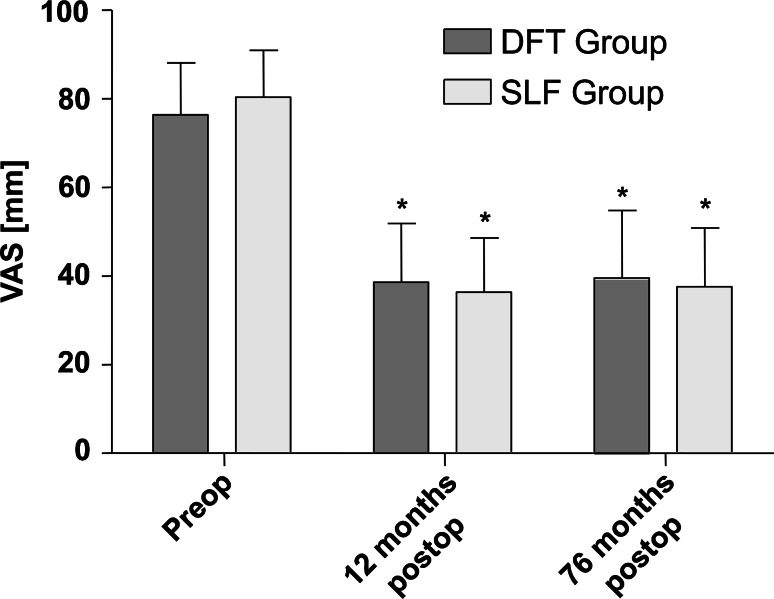

No significant differences in the ODI or VAS were observed between the groups at any time point during follow-up (influence of treatment type). The overall influence of time was significant (p VAS < 0.001; p ODI < 0.001). Results are presented in Figs. 4 and 5.

Fig. 4.

Oswestry disability index (ODI) between groups over follow-up. Whiskers indicate single standard deviation. Asterisks mean significance (p < 0.05) compared with preoperative status

Fig. 5.

Visual analog scale (VAS) between groups over follow-up. Whiskers indicate single standard deviation. Asterisks mean significance (p < 0.05) compared with preoperative status

The patients’ subjective satisfaction with the surgical outcome did not differ between the two groups at any time point (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patient’s satisfaction

| Time | Variable | SLF group (n = 25) (%) | DFT group (n = 21) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 week postop | Excellent/good | 76.0 | 71.4 |

| 12 months postop | Excellent/good | 68.0 | 66.7 |

| Final follow-up | Excellent/good | 64.0 | 61.9 |

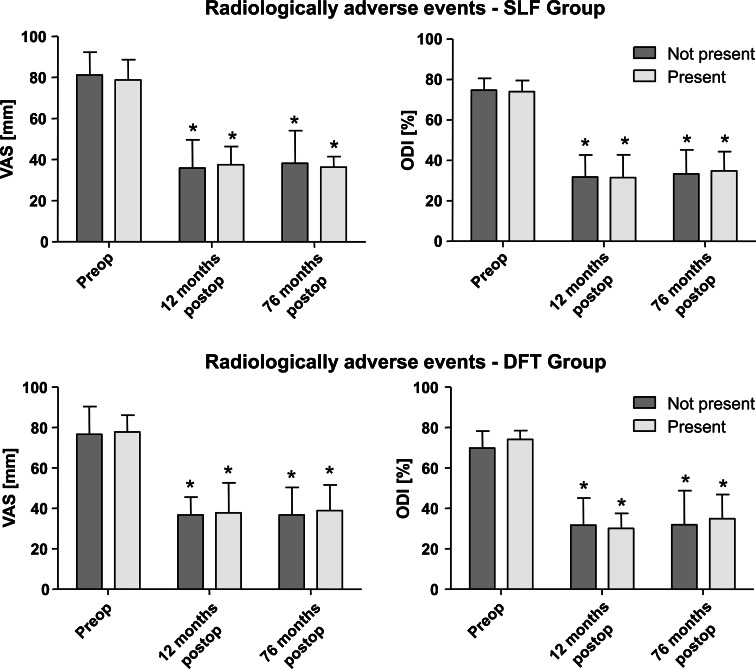

Sub-grouping of radiologically apparent adverse events at final follow-up resulted in eight patients [two patients with radiological non-union and six patients with progression of adjacent segment degeneration (PASD)] in the SLF group and nine patients in the DFT group (two patients with radiological non-union, one patient with rod failure, two with screw failure, one with instability, one with fusion of the dynamically fixated segment, and two with progression of degeneration in the segment adjacent to dynamic fixation). Comparison between radiologically symptomatic and asymptomatic sub-groups within the SLF and DFT groups revealed no significant influence of radiologically adverse events on VAS (p SLF = 0.849; p DFT = 0.693) or ODI (p SLF = 0.964; p DFT = 0.666); influence of time was significant (p VAS < 0.001; p ODI < 0.001). For results see Table 2 and Fig. 6. Furthermore, the sub-group of adjacent segment degeneration progression alone (excluding patients with radiological non-fusion) within the SLF group was tested for clinical differences. Results show no significant influence of the PASD alone on the clinical outcome, with respect to VAS and ODI (p VAS = 0.718; p ODI = 0.712), throughout follow-up. This test was not performed in the DFT group because of the small number of patients presenting PASD.

Fig. 6.

Clinical results (ODI and VAS) between sub-groups with and without radiologically apparent adverse events in (upper row) the SLF group and (lower row) the DFT group over follow-up. Whiskers indicate single standard deviation. Asterisks mean significance (p < 0.05) compared with preoperative status

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge this is the first prospective study to evaluate the outcome of dynamic fixation of a radiologically initially degenerated, but clinically asymptomatic, segment adjacent to fusion. Additionally, this is the first study to present clinical and radiological medium-term follow-up results after such instrumentation.

Within this study, we demonstrated that a PASD can be reduced by additional dynamic fixation of this segment. Nevertheless, we also observed progression of degeneration in the segment adjacent to dynamic fixation and an increased rate of implant-associated complications in the DFT group. Despite the radiological benefit of avoiding degeneration progression, we were not able to detect clinical differences in the outcome between SLF and fusion with dynamic adjacent segment fixation.

Limitations of the study arise from the small number of patients recruited and present at final follow-up. Nothing can be concluded presently about the effects of a dynamic stabilization on clinically symptomatic initially degenerated segments. Another possible restriction is the employment of a Dynesys®-based implant. The Dynesys® implant is known not to physiologically restore stability in every plane of motion. MRI as well as cadaver studies have shown that it preserves but limits motion in extension, flexion and lateral bending, but does not completely compensate for increases in rotational movement, when compared with the intact spine [1, 35]. In our own biomechanical study and another [34, 36], it was demonstrated that stability resulting from Dynesys® is very close to that of rigid fixation. Furthermore, stiffness can be varied by changing the spacer length, which is defined individually by the surgeon during the operation [22]. This may explain the fusion and the progression of degeneration, observed in one patient each, in the dynamically fixated segment. Nevertheless, Dynesys® is one of the longest used and best evaluated (clinically and biomechanically) dynamic implants available. A possible disadvantage may arise from the relatively oblique position of the Dynesys® spacer, when using the connector between the rigid and dynamic posterior fixations. This was necessary to maintain facet joint function of the segment adjacent to the fusion. In the biomechanical evaluation of the construct used in this study, we demonstrated that hyper-mobility resulting from SLF can be compensated, but over-compensated, by additional dynamic fixation [36]. Two-level instrumentation led to a particular increase of motion in the segment superior to it, regardless of whether dynamic or rigid fixation was applied. Additionally, multi-level stabilization seems to increase rate of incidence of degeneration of the segment adjacent to stabilization [37]. This and the relative rigidity of the Dynesys® implant could be an explanation for the degeneration process of the segments adjacent to dynamic fixation, observed in two patients of the present study. PASD after single-level Dynesys® has been described by Schaeren et al. [32] in up to 47% after 4 years.

Since almost nothing was known about the impact of the pre- and postoperative sagittal balance of the patients on success of spinal surgery at time of surgery, a spinal balance analysis was not performed but for sure should be considered for extension of surgery. Therefore, a postoperative sagittal imbalance could have had a negative influence on PASD [18, 23]. Another factor which possibly biased the study could result from preoperative discography itself performed at the adjacent segment. Carragee et al. [2] reported of an increased rate of disc degeneration after 10 years post intervention. Nevertheless, to our knowledge discography is the only test to prove whether radiologic disc degeneration is painful or not. Additionally, at the time we initiated the study, this knowledge was not available.

There was an impressive rate of radiologically apparent implant-associated adverse events in the DFT group. We suggest that the forces conveyed from the dynamic implant lead to increased stress on the rigid fixation over time. Therefore, the number of implant failures will increase over time, as observed in this study at final follow-up. New implant designs can possibly reduce such failures: a variety of dynamic implants have been and are being developed, which may reduce the disadvantages and maximize the benefits of dynamic stabilization [15, 38, 39].

Despite the high implant failure rate in the DFT group, we surprisingly could not detect a clinical disadvantage (except in 1 patient), which would have led to re-operation. The other surprise was a comparatively high number (24%) in the SLF group showing PASD. Nevertheless, the sub-group of patients with this degeneration progression performed equally compared with the other patients of SLF group, and were clinically asymptomatic (except in 1 patient). The radiological incidence rate of progressive degeneration in the initially degenerated segment adjacent to fusion has been described to vary between 5.2 and 100%, whereas only 12.2–18.5% seem to be symptomatic in patients with transpedicular fixation [24]. This may explain the high number of asymptomatic changes observed in this study.

Radiological fusion rates in the present study do not differ significantly from fusion results in the literature [31]. Nevertheless, radiographic fusion evaluation has to be interpreted carefully. Thin-slice computed tomography is a more precise fusion evaluation method [31], but was not employed in the present study, in order to limit radiation exposure. To compensate for this, restrictive criteria were chosen for radiographic fusion evaluation. Despite the rate of implant failure in the fusion segment in the DFT group, implant failures did not lead to a higher radiological rate of non-fusion.

Clinical scores of both groups also ranked at a level comparable to that in other studies where SLF was performed [12, 21]. We could not observe a benefit in either applying or omitting additional dynamic fixation. However, implant failure and adjacent segment degeneration progression did not result in an inferior clinical outcome. It is possible that clinical differences could be seen after an even longer post-operative period. Further studies are needed to test this.

In conclusion, the lower number of cases with PASD when dynamically fixated was accompanied by a higher number of implant failures and a shift of adjacent segment degeneration to the superior segment. Additionally, employing the Allospine™ Dynesys® Transition implant did not lead to clinical superiority in patients with clinically asymptomatic initially degenerated adjacent segments after medium-term follow-up. Following this, we do not recommend dynamic fixation of a clinically asymptomatic, initially degenerated segment adjacent to fusion.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

References

- 1.Beastall J, Karadimas E, Siddiqui M, Nicol M, Hughes J, Smith F, Wardlaw D. The Dynesys lumbar spinal stabilization system: a preliminary report on positional magnetic resonance imaging findings. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:685–690. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000257578.44134.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carragee EJ, Don AS, Hurwitz EL, Cuellar JM, Carrino J, Herzog R. 2009 ISSLS prize winner: does discography cause accelerated progression of degeneration changes in the lumbar disc: a ten-year matched cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2338–2345. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ab5432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng BC, Gordon J, Cheng J, Welch WC. Immediate biomechanical effects of lumbar posterior dynamic stabilization above a circumferential fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2551–2557. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318158cdbe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chou WY, Hsu CJ, Chang WN, Wong CY. Adjacent segment degeneration after lumbar spinal posterolateral fusion with instrumentation in elderly patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:39–43. doi: 10.1007/s004020100314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colloca CJ, Keller TS, Peterson TK, Seltzer DE. Comparison of dynamic posteroanterior spinal stiffness to plain film radiographic images of lumbar disk height. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2003;26:233–241. doi: 10.1016/S0161-4754(03)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dupuis PR, Yong-Hing K, Cassidy JD, Kirkaldy-Willis WH. Radiologic diagnosis of degenerative lumbar spinal instability. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1985;10:262–276. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198504000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etebar S, Cahill DW. Risk factors for adjacent-segment failure following lumbar fixation with rigid instrumentation for degenerative instability. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:163–169. doi: 10.3171/spi.1999.90.2.0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, O’Brien JP. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire. Physiotherapy. 1980;66:271–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujiwara A, Tamai K, Yamato M, An HS, Yoshida H, Saotome K, Kurihashi A. The relationship between facet joint osteoarthritis and disc degeneration of the lumbar spine: an MRI study. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:396–401. doi: 10.1007/s005860050193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerbershagen HU, Lindena G, Korb J, Kramer S. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic pain. Schmerz. 2002;16:271–284. doi: 10.1007/s00482-002-0164-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghiselli G, Wang JC, Bhatia NN, Hsu WK, Dawson EG. Adjacent segment degeneration in the lumbar spine. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1497–1503. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200407000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glassman S, Gornet MF, Branch C, Polly D, Jr, Peloza J, Schwender JD, Carreon L. MOS short form 36 and Oswestry disability index outcomes in lumbar fusion: a multicenter experience. Spine J. 2006;6:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hambly MF, Wiltse LL, Raghavan N, Schneiderman G, Koenig C. The transition zone above a lumbosacral fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1785–1792. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199808150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanayama M, Hashimoto T, Shigenobu K, Togawa D, Oha F. A minimum 10-year follow-up of posterior dynamic stabilization using Graf artificial ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1992–1996. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318133faae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YS, Zhang HY, Moon BJ, Park KW, Ji KY, Lee WC, Oh KS, Ryu GU, Kim DH. Nitinol spring rod dynamic stabilization system and Nitinol memory loops in surgical treatment for lumbar disc disorders: short-term follow up. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22:E10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar MN, Baklanov A, Chopin D. Correlation between sagittal plane changes and adjacent segment degeneration following lumbar spine fusion. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:314–319. doi: 10.1007/s005860000239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar MN, Jacquot F, Hall H. Long-term follow-up of functional outcomes and radiographic changes at adjacent levels following lumbar spine fusion for degenerative disc disease. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:309–313. doi: 10.1007/s005860000207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labelle H, Roussouly P, Chopin D, Berthonnaud E, Hresko T, O’Brien M. Spino-pelvic alignment after surgical correction for developmental spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1170–1176. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leone A, Guglielmi G, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Bonomo L. Lumbar intervertebral instability: a review. Radiology. 2007;245:62–77. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2451051359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS, Carter JR. Imaging of degenerative disk disease. Radiology. 1988;168:177–186. doi: 10.1148/radiology.168.1.3289089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemeyer T, Bovingloh AS, Halm H, Liljenqvist U. Results after anterior-posterior lumbar spinal fusion: 2–5 years follow-up. Int Orthop. 2004;28:298–302. doi: 10.1007/s00264-004-0577-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niosi CA, Zhu QA, Wilson DC, Keynan O, Wilson DR, Oxland TR. Biomechanical characterization of the three-dimensional kinematic behaviour of the Dynesys dynamic stabilization system: an in vitro study. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:913–922. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0948-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park JY, Cho YE, Kuh SU, Cho JH, Chin DK, Jin BH, Kim KS. New prognostic factors for adjacent segment degeneration after one-stage 360 degrees fixation for spondylolytic spondylolisthesis: special reference to the usefulness of pelvic incidence angle. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:139–144. doi: 10.3171/SPI-07/08/139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park P, Garton HJ, Gala VC, Hoff JT, McGillicuddy JE. Adjacent segment disease after lumbar or lumbosacral fusion: review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:1938–1944. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000137069.88904.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penta M, Sandhu A, Fraser RD. Magnetic resonance imaging assessment of disc degeneration 10 years after anterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:743–747. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199503150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pihlajamaki H, Bostman O, Ruuskanen M, Myllynen P, Kinnunen J, Karaharju E. Posterolateral lumbosacral fusion with transpedicular fixation: 63 consecutive cases followed for 4 (2–6) years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:63–68. doi: 10.3109/17453679608995612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putzier M, Schneider SV, Funk JF, Tohtz SW, Perka C. The surgical treatment of the lumbar disc prolapse: nucleotomy with additional transpedicular dynamic stabilization versus nucleotomy alone. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:E109–E114. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000154630.79887.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Putzier M, Strube P, Funk JF, Gross C, Monig HJ, Perka C, Pruss A. Allogenic versus autologous cancellous bone in lumbar segmental spondylodesis: a randomized prospective study. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:687–695. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0875-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahm MD, Hall BB. Adjacent-segment degeneration after lumbar fusion with instrumentation: a retrospective study. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:392–400. doi: 10.1097/00002517-199610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohlmann A, Burra NK, Zander T, Bergmann G. Comparison of the effects of bilateral posterior dynamic and rigid fixation devices on the loads in the lumbar spine: a finite element analysis. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1223–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0292-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos ER, Goss DG, Morcom RK, Fraser RD. Radiologic assessment of interbody fusion using carbon fiber cages. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:997–1001. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000061988.93175.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schaeren S, Broger I, Jeanneret B. Minimum four-year follow-up of spinal stenosis with degenerative spondylolisthesis treated with decompression and dynamic stabilization. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:E636–E642. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817d2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmoelz W, Huber JF, Nydegger T, Claes L, Wilke HJ. Influence of a dynamic stabilisation system on load bearing of a bridged disc: an in vitro study of intradiscal pressure. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1276–1285. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-0032-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmoelz W, Huber JF, Nydegger T, Dipl I, Claes L, Wilke HJ. Dynamic stabilization of the lumbar spine and its effects on adjacent segments: an in vitro experiment. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:418–423. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200308000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stoll TM, Dubois G, Schwarzenbach O. The dynamic neutralization system for the spine: a multi-center study of a novel non-fusion system. Eur Spine J. 2002;11(Suppl 2):S170–S178. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0438-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strube P, Tohtz SW, Hoff E, Gross C, Putzier M (2010) Dynamic stabilization adjacent to single-level fusion - part I: biomechanical effects on lumbar spinal motion. Eur Spine J (submitted, in review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Yang JY, Lee JK, Song HS. The impact of adjacent segment degeneration on the clinical outcome after lumbar spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:503–507. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181657dc3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yue JJ, Timm JP, Panjabi MM, Jaramillo-de la Torre J. Clinical application of the Panjabi neutral zone hypothesis: the Stabilimax NZ posterior lumbar dynamic stabilization system. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22E:12. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu Q, Larson CR, Sjovold SG, Rosler DM, Keynan O, Wilson DR, Cripton PA, Oxland TR. Biomechanical evaluation of the total facet arthroplasty system: 3-dimensional kinematics. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:55–62. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250983.91339.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]