Abstract

Linezolid belongs to a new class of synthetic antimicrobial agent that is effective for a variety of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections including bone and joint MRSA infections, but the effectiveness of linezolid for the treatment of MRSA spine infection remains controversial. In this study, we investigated the diffusion of linezolid or vancomycin into normal rabbit spinal tissues to determine the adequacy of linezolid for the treatment of spinal infection. The penetration efficacy of linezolid into the annulus fibrosus, nucleus pulposus, and vertebral bone (10, 8, and 10%, respectively) was lower than that of vancomycin (27, 11, and 14%, respectively). The penetration efficacy of linezolid into the bone marrow and iliopsoas muscle (88 and 84%, respectively), however, was higher than that of vancomycin (67 and 9%, respectively). These results suggest that linezolid is inadequate for the treatment of spine infection limited to the intervertebral disc, but may be effective for the treatment of infection extending into the muscle and bone marrow, such as in vertebral osteomyelitis, iliopsoas abscess, and postsurgical infection.

Keywords: Linezolid, Penetration, Spine infection, Pyogenic spondylodiscitis, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Introduction

The number of patients with pyogenic spondylodiscitis has increased over the past few decades [24], probably due to the increase in the number of immunosuppressed patients with comorbid medical problem, such as diabetes mellitus, HIV infection, collagen diseases, neoplastic diseases, intravenous drug use, and others [2, 9]. Further, the number of iatrogenic spinal infections after injection therapy or surgeries is also increasing [11]. Contemporary medical treatment for these serious systemic diseases prolongs the life of the patients, leading to more frequent opportunities for these patients to contract spinal infections.

The most common organism isolated from infected spine tissues is Staphylococcus aureus, and 30–40% of nosocomially acquired Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains are methicillin resistant [5, 20]. Glycopeptide antibiotics such as vancomycin are currently the gold standard treatment for MRSA infection [16], but these drugs sometimes fail in the treatment of MRSA spondylodiscitis, possibly due to the poor penetration of the antibiotics into the intervertebral discs and vertebral bone. In addition, there is increasing concern over the emergence of glycopeptide resistance in Gram-positive organisms [1, 28], as well as difficulties in managing patients intolerant to these agents. Therefore, the need for alternative therapeutic agents for this condition is increasing.

Linezolid is a relatively new synthetic antimicrobial agent developed to treat serious Gram-positive infections, including MRSA and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. It has excellent oral bioavailability, a favorable pharmacokinetic and toxicity profile (65% of clearance occurs by non-renal mechanisms) [27], and rapid and high penetration into the bones and joints [22, 23]. According to the study by Rana et al. [22] penetration efficacy of linezolid into osteo-articular tissues was 91.9% in synovial fluid, 82.1% in synovium, 83.5% in muscle, and 40.1% in bone. There are several case reports showing that linezolid successfully treated post-surgical pyogenic osteoarthritis that was resistant to glycopeptide antibiotics [4, 18]. Therefore, linezolid may have an important clinical role in the treatment of MRSA infections in the orthopedic field, especially for intra-articular space infections where the penetration of antibiotics is unpredictable because of the lack of blood circulation.

Although these findings suggest that linezolid may be a clinically attractive alternative to vancomycin for MRSA spinal infections, there is no consensus on the effectiveness of linezolid in the treatment of these conditions. While Conaughty et al. [6] suggested that linezolid was not efficacious for the treatment of disc infection from the result of an experimental rabbit study, there are several case reports demonstrating successful treatment of spinal infections that were resistant to other antibiotic therapy [26]. Furthermore, to our knowledge, there is a lack of information regarding the penetration of linezolid into the spinal tissues. In this study, we investigated the diffusion of linezolid into normal rabbit spinal tissues to determine the adequacy of linezolid for the treatment of spinal infection.

Materials and methods

Animal studies

Thirty adult male New Zealand white rabbits aged 16–22 weeks (3.2–3.7 kg) were obtained from CLEA Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). The experimental protocol was approved by the institutional animal study committee. Linezolid (ZYVOX™, Pfizer Inc., NY) was administered intravenously (IV) by ear vein bolus to 18 rabbits, and 6 rabbits were killed at each time point. Vancomycin (Shionogi & Co., Ltd, Japan) was administered IV to 12 rabbits for comparison, and 4 rabbits were killed at each time point. Tissue penetration of the drugs was studied at 0.33, 1, and 4 h after IV administration. Each animal received an IV dose of 20 mg/kg linezolid or 40 mg/kg vancomycin over a period of 3 min. The animals were killed at the indicated time points by an IV injection of pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg body weight). Blood plasma was separated by centrifugation and stored at −80°C for determination of the antibiotic levels. Intervertebral disc, vertebral bone, iliopsoas muscle, and bone marrow tissue samples were collected from the thoracic and lumbar spine. Intervertebral disc tissue was then divided into annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus tissues. Tissue samples were weighed and frozen at −80°C prior to assay.

Drug assay

Linezolid was extracted from the tissue samples using the method described previously with slight modification [22]. Briefly, tissue samples were ground, weighed, mixed with a fivefold (or threefold in the case of bone marrow) volume of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 mg/ml collagenase and 1 mM EDTA. The mixture was then allowed to stand at 37°C for 30 min and then twice the volume of PBS was added and the mixture was homogenized twice using an ultrasonic homogenizer (U200H, IKA Labortechnik, Staufen, Germany) for 10 s each with 30% amplitude. PBS and an internal standard (20 μM mepilozol in methanol) were added to an aliquot of the homogenate and the mixture was allowed to stand at 37°C for 30 min. The same volume of acetonitrile was then added and the solution was mixed and centrifuged at 14,000×g for 15 min. The supernatant was evaporated in vacuo, and the residue was reconstituted with distilled water. Collagenase was not used in the preparation of bone marrow and vertebral bone samples. Plasma samples were prepared as follows: 150 μl serum was mixed with 150 μl methanol and 20 μl internal standard (20 μM mepilozol in methanol) and then mixed with a vortex mixer for 30 s. After removal of the protein by centrifugation at 14,000×g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatant was injected into a high performance liquid chromatography system for quantification [21, 29]. The stationary phase was an ERC ODS-1161 (6.0 mm ID × 100 mm) column (Yokohamarika Co., Yokohama, Japan). The mobile phase was a mixture of acetonitrile and 50 mM KH2PO4 (20:80). The flow rate was 1.0 ml/min and column temperature was 55°C. A wavelength of 251 nm was used for ultraviolet detection. Linezolid recovery from the tissue samples using this method was almost 100% [17]. The linezolid retention time was 7.5 min.

Tissue concentrations of vancomycin were measured by fluorescence polarization immunoassay (FPIA) using the TDx FPIA kit (Abbott Japan. Co., Ltd.). FPIA is a clinically used measurement for the determination of vancomycin levels in tissues and proved to have good correlation with the data measured by HPLC [10, 12, 19]. After tissue samples were prepared in the same manner as described above, the vancomycin concentration in the spinal tissues was quantified according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, unlabeled vancomycin in the tissues competes with fluorescein-labeled vancomycin (tracer) for limited antibody sites. The relationship between the concentration of unlabeled drug and polarization is established with standard solutions containing 0, 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μg/ml vancomycin. The obtained values are subjected to a nonlinear least-squares curve fit, which is used to determine the concentration of vancomycin in the tissues.

Antimicrobial studies

Microbiologic studies were performed with the MRSA strain ATCC 33591 and a clinically isolated MRSA strain as the indicator. The agar diffusion technique was used as previously described [8]. MRSA was seeded (1.5 × 108 colony-forming units/ml) on the surface of Mueller–Hinton agar plates. Sterile paper discs (6 mm in diameter) were allowed to absorb 30 μl of the tissue sample extract. The discs were then placed on the surface of the agar and incubated with bacterial inoculum for 24 h at 37°C. The zone of inhibition of bacterial growth was compared with the zones obtained with commercially available standards (linezolid solution diluted to 10 and 20 μg/ml).

Results

Plasma and tissue concentrations of antibiotics

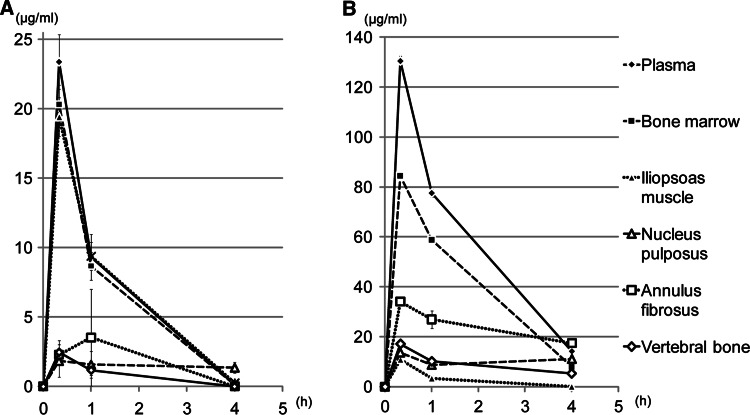

Single-dose pharmacokinetic parameters of linezolid and vancomycin are shown in Fig. 1. Plasma concentrations of linezolid decreased bi-exponentially after IV injection, whereas plasma vancomycin decreased at a slower pace (Fig. 1). Blood-elimination half-life of the antibiotics was approximately 0.5–1 h for linezolid and approximately 1–1.5 h for vancomycin in this rabbit model.

Fig. 1.

Plasma and tissue concentrations of (a) linezolid and (b) vancomycin after single-dose IV injection. Concentration is expressed in micrograms per gram of wet tissue weight; mean ± standard deviation, h hours

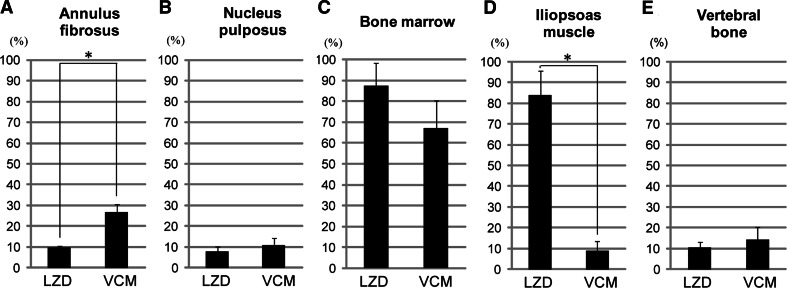

Changes in the concentrations of linezolid in the bone marrow and iliopsoas muscle were similar to that in plasma, and the penetration efficacy of linezolid in those tissues at 0.33 h after administration was 88 and 84%, respectively. The linezolid concentrations in the annulus fibrosus, nucleus pulposus, and vertebral bone were considerably lower than that in plasma, and the penetration into these tissues was 10% (annulus fibrosus), 8% (n. pulposus), and 10% (vertebral bone). The distribution of vancomycin in the spinal tissues differed from that of linezolid. The penetration of vancomycin into the annulus fibrosus was 27%, which was significantly higher than that of linezolid. The penetration of vancomycin into the iliopsoas muscle, however, was significantly lower than that of linezolid (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Penetration efficacy into (a) annulus fibrosus, (b) nucleus pulposus, (c) bone marrow, (d) iliopsoas muscle, and (e) vertebral bone at 0.33 h after linezolid or vancomycin injection. Penetration efficiency was defined as tissue concentration/plasma concentration ×100 (%). *P < 0.05

Antimicrobial effect

The antimicrobial effects of linezolid in the extracted tissue samples of plasma, bone marrow, and the iliopsoas muscle were confirmed by measuring the zones of inhibition of bacterial growth (Table 1). An inhibition zone could not be detected for the vertebral bone and nucleus pulposus samples (Table 1), and the same results were obtained with analogous samples from rabbits injected with vancomycin (Table 2). Blood plasma and bone marrow extract had inhibition zone diameters equivalent to that obtained with 20 μg/ml linezolid or 120 μg/ml vancomycin, which were the concentrations obtained from drug assay with HPLC or FPIA. To generate liquid extracts from solid tissues (iliopsoas muscle, bone, nucleus pulposus), we diluted PBS to twice the original volume. Iliopsoas muscle extract had an inhibition zone diameter nearly equivalent to that obtained with 10 μg/ml linezolid, about half the expected value due to dilution. Similar results were obtained in experiments using both ATCC 33591 and a clinically isolated MRSA strain (Table 1). Iliopsoas muscle extract obtained from rabbits injected with vancomycin, meanwhile, had no inhibition zone diameter (Table 2).

Table 1.

Zone diameter of bacterial growth inhibition obtained with samples from rabbits injected with linezolid

| Strain | Zone diameter (mm) | Tissue specimens | LZD (control) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Bone marrow | Iliopsoas muscle | Vertebral bone | Nucleus pulposus | 20 μg/ml | 10 μg/ml | ||

| ATCC 33591 | Median | 13.2 | 13.8 | 9.4 | ND | ND | 13.4 | 9.6 |

| Range | 12.2–14.4 | 12.0–15.8 | 8.4–10.0 | ND | ND | 12.0–14.0 | 8.4–10.0 | |

| Clinically isolated | Median | 14.4 | 13.8 | 7.9 | ND | ND | 13.4 | 9.3 |

| Range | 13.3–14.5 | 13.2–15.1 | 7.2–8.6 | ND | ND | 13.2–13.8 | 9–9.7 | |

ND not detected

Table 2.

Zone diameter of bacterial growth inhibition obtained with samples from rabbits injected with vancomycin

| Strain | Zone diameter (mm) | Tissue specimens | VCM (control) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Bone marrow | Iliopsoas muscle | Vertebral bone | Nucleus pulposus | 120 μg/ml | 30 μg/ml | ||

| ATCC 33591 | Median | 11.2 | 11.1 | ND | ND | ND | 12.2 | 10.5 |

| Range | 10.7–11.7 | 11–11.3 | ND | ND | ND | 11.8–12.6 | 10.3–10.8 | |

| Clinically isolated | Median | 12 | 11.4 | ND | ND | ND | 10.9 | 8.6 |

| Range | 11.7–12.3 | 11.0–12.0 | ND | ND | ND | 10.4–11.4 | 7.2–9.0 | |

ND not detected

Discussion

In this study, we reported the penetration data of linezolid and vancomycin into spine tissues to assess the adequacy of using these antibiotics for MRSA spine infection. Our findings complement those published in a similar study by Conaughty et al. [6]. Conaughty et al. suggested that vancomycin was superior to linezolid for the treatment of disc space infection based on the results that vancomycin, but not linezolid, significantly reduced MRSA bacterial loads in a rabbit iatrogenic intervertebral disc infection model. This finding, however, cannot apply to multiple tissue infection cases such as spondylodiscitis, which are much more common clinically [13]. Meanwhile, the penetration data obtained in our study can apply to various types of MRSA spine infections, though it did not directly prove the efficacy of each drug in an in vivo infection model. Considering the fact that most hematogenous and postsurgical infection cases develop spondylodiscitis [3, 13, 14], the results of this study have important implications to optimizing the management of MRSA spine infections.

The main finding of the present study is that the tissue distribution of linezolid in spinal tissues is considerably different from that of vancomycin. This fact suggests that we should select proper antibiotics according to the distribution and condition of infection in each spinal infection case. Hematogenous spondylodiscitis usually arises from the endplate and intervertebral disc, and extends to vertebral osteomyelitis, iliopsoas abscess, and epidural abscess. Postsurgical spinal infection induces a variety of conditions and distributions according to the surgical procedure, but it is usually accompanied with extended soft tissue infection such as deep muscle infection and subcutaneous phlegmonous infection. Since the recent development of diagnostic techniques such as contrast-enhanced MRI make it possible to identify the distribution of infection, we believe that we can treat the MRSA spinal infection patient more effectively with the knowledge of tissue distribution of linezolid and vancomycin.

In the present study, linezolid was only sparsely distributed in the intervertebral discs, suggesting that linezolid was not adequate for the treatment of MRSA disc infection. Because the adult intervertebral disc is an avascular tissue and substance transportation occurs via diffusion from vertebral capillaries through the cartilaginous endplate [30], it is not surprising that pharmacologic agents do not penetrate very well into this tissue. Glycopeptide antibiotics such as vancomycin, however, are reported to penetrate into intervertebral discs [26]. Penetration of vancomycin into the intervertebral discs was confirmed in the present study, although penetration into nucleus pulposus was lower than that in previous reports [6, 26]. Therefore, glycopeptides are better suited for the treatment of MRSA disc infection than linezolid. These data are consistent with those obtained by Conaughty et al. [6].

A possible reason for the difference in penetration into the intervertebral disc between linezolid and glycopeptides is the difference in the electrical charge of the molecules, as vancomycin is positively charged and linezolid is theoretically uncharged [27]. In general, penetration of drugs from the blood into the tissues depends on several physical and chemical characteristics of the molecule, such as size, binding affinity to proteins, and polarity [30]. Based on these characteristics, linezolid has advantageous characteristics for tissue penetration, including a much smaller size compared to glycopeptide antibiotics and a low binding capacity to proteins. In fact, compared to glycopeptides, linezolid has excellent penetration into many tissues in which glycopeptide antibiotics do not penetrate well, such as soft tissues and epithelial lining fluid, which bathes the pulmonary alveoli [15]. Several previous studies, however, have reported that the molecular polarity of antibiotics is a more dominant factor for penetration into the intervertebral discs. Scuderi et al. [26] reviewed studies related to the penetration of antimicrobial agents into the intervertebral disc and found that antimicrobial agents able to diffuse into the nucleus pulposus were positively charged, and those unable to penetrate were negatively charged. Thus, uncharged linezolid might be unfavorable for penetration into the intervertebral disc.

Despite the poor penetration of linezolid into the intervertebral disc, linezolid was highly distributed in the bone marrow and iliopsoas muscle, indicating that it may be effective for treating MRSA spine infections involving the vertebral body and surrounding muscles. The linezolid penetration efficacy into the iliopsoas muscle was more than 80% that of the plasma concentration, whereas the vancomycin penetration efficacy was less than 10% that of the plasma concentration. Additionally, we demonstrated the antimicrobial ability of linezolid penetrated into iliopsoas muscle, which we did not observe with vancomycin. Considering the fact that hematogenous spondylodiscitis and postoperative spinal infection are more likely to occur clinically than disc infection alone, it is possible that linezolid is better for treating these conditions than glycopeptides. Linezolid has been compared favorably to glycopeptides in the treatment of soft tissue infection, and therefore it may be an efficacious treatment, particularly against surgical site infections involving subcutaneous soft tissue infection and extensive spinal infection with the development of an iliopsoas abscess.

In selecting antibiotics for MRSA spine infection in clinical practice, we need to take other factors as well as penetration of the drugs into consideration. Concomitant medical problems, condition of infection, and combination therapy are important factors in these determinations. In the case of the elderly and/or immunosuppressed patient, which are the most common background of MRSA spondylodiscitis, we speculated that linezolid had some advantages over vancomycin. These patients often have renal failure or easily develop drug-induced renal failure. Therefore linezolid, which has no toxic effects on kidney or liver, is preferable for these patients to vancomycin.

To avoid toxicity and maintain therapeutic level, vancomycin dosage may take time to get adjusted. Conversely, linezolid has nearly 100% bioavailability and does not require dosage adjustment regardless of age, and renal and hepatic function. Therefore, linezolid also seems valuable for serious infection cases that require urgent treatment. Since immunosuppressive patients with MRSA spondylodiscitis sometimes develop sepsis and have high mortality rate [3], the selection of drugs might be critical. Regardless of these advantages of linezolid, we should avoid using linezolid in cases with preexisting pancytopenia because of a risk of myelosuppression.

It is also important to consider which, linezolid or vancomycin, is preferable when combined with surgical intervention. Although penetration of vancomycin into intervertebral disc was better than that of linezolid, the results of our antimicrobial assay indicated that neither vancomycin nor linezolid can control disc infection by itself. Besides, staphylococcus produces biofilm on bone surface that interferes with the antimicrobial effect of drugs, even though sufficient drug reaches the bone marrow or bone. Therefore, a combination of surgical treatment and antimicrobial therapy is mandatory for most MRSA spine infection cases and antibiotics are expected to play roles in controlling remaining infection after the surgery. Although the results of this study do not allow us to make a definitive conclusion, linezolid may be more promising and safer than vancomycin based on the fact that linezolid highly distributes into the spine and its surrounding tissues except intervertebral disc and has less risk for drug-induced renal failure that is likely to occur during the perioperative period due to multiple drug use.

It should be noted that, although the rabbit model is an established one for antibiotic kinetic studies, the estimated half-life of linezolid in rabbit is four times faster than that in humans [6, 7, 13, 25, 26], while vancomycin shows similar drug kinetics between rabbit and human. This difference in linezolid drug kinetics between rabbit and human could be caused by its unique metabolism: unlike other antibiotics, it is mainly metabolized by whole body with non-specific oxidation and not by the liver or kidney [27]. Therefore, the data obtained in the rabbit model allows us to analyze the tissue penetration efficacy of linezolid, but does not allow comparing longitudinal kinetics between linezolid and vancomycin. These interspecies differences in drug kinetics also made it difficult to compare the tissue accumulation of drugs after multiple dosing, which is important in terms of the prediction of efficiency and the risk for side effect of drugs. The clinically approved dosing regimen in humans is multiple dosing every 12 h. We did not adhere to these guidelines because in rabbits, the tissue concentration of linezolid fell below the measurable level 6 h after administration. Though the rabbit model has been used as a standard to investigate the penetration of antibiotics into spine tissues, there were limitations in studying linezolid.

There are some other limitations to this study. First, the animal model used in this study does not involve an infection. Since inflammation could change penetration efficacy of drug to tissues, the data might change in infected condition. Despite that, there are no available data published regarding the penetration of linezolid to normal spinal tissues and therefore we think that the data obtained in this study could be helpful to predict the efficacy of linezolid against spinal infections. Besides, it is difficult to make homogenous infection model to get reproducible tissue concentration data. Second, rabbit nucleus consists predominantly of notochordal cells, giving the rabbit nucleus a completely different, vacuolated and fluid-rich structure, as compared to the adult human nucleus, which is more fibrous and less hydrated. This is very likely to influence the diffusion capacity of antibiotics and, therefore, the disc diffusion data in rabbit may be different from that in the adult human. Third, the doses used in this study were twice the clinical dose used in humans. We did this because we could not accurately determine the linezolid levels in the intervertebral disc tissues due to low penetration and fast metabolism when we used the clinical human dose. To confirm the findings of this study, further studies measuring the tissue concentration in humans and clinical studies of the efficacy of linezolid for the treatment of spine infection must be performed.

In conclusion, the findings of the present study indicate that linezolid insufficiently penetrated into the intervertebral disc, which is the site of early involvement as well as the main focus of hematogenous pyogenic spondylodiscitis, suggesting that linezolid is inadequate for the treatment of MRSA disc infection. Considering the excellent distribution of linezolid into the bone marrow and muscle, however, linezolid may be effective in the treatment of MRSA spinal infections that extend to the muscles and bone marrow, such as in advanced spondylodiscitis, iliopsoas abscess, and surgical site infection after spine surgery.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control, Prevention (CDC) Staphylococcus aureus resistant to vancomycin–United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;26:565–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acosta FL, Galvez LF, Jr, Aryan HE, Ames CP. Recent advances: infections of the spine. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2006;5:390–393. doi: 10.1007/s11908-006-0050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Nammari SS, Lucas JD, Lam KS. Hematogenous methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus spondylodiscitis. Spine. 2007;32:2480–2486. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318157393e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bassetti M, Vitale F, Melica G, Righi E, Di Biagio A, Molfetta L, Pipino F, Cruciani M, Bassetti D. Linezolid in the treatment of Gram-positive prosthetic joint infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;3:387–390. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carragee EJ. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;6:874–880. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199706000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conaughty JM, Chen J, Martinez OV, Chiappetta G, Brookfield KF, Eismont FJ. Efficacy of linezolid versus vancomycin in the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus discitis: a controlled animal model. Spine. 2006;22:E830–E832. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000241065.19723.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cottagnoud P, Gerber CM, Acosta F, Cottagnoud M, Neftel K, Tauber MG. Linezolid against penicillin-sensitive and -resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;6:981–985. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Currier BL, Banovac K, Eismont FJ. Gentamicin penetration into normal rabbit nucleus pulposus. Spine. 1994;23:2614–2618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fang A, Hu SS, Endres N, Bradford DS. Risk factors for infection after spinal surgery. Spine. 2005;12:1460–1465. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166532.58227.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farin D, Piva GA, Gozlan I, Kitzes-Cohen R. A modified HPLC method for the determination of vancomycin in plasma and tissues and comparison to FPIA (TDX) J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1998;3:367–372. doi: 10.1016/S0731-7085(98)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gasbarrini AL, Bertoldi E, Mazzetti M, Fini L, Terzi S, Gonella F, Mirabile L, Barbanti Brodano G, Furno A, Gasbarrini A, Boriani S. Clinical features, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to haematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;1:53–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graziani AL, Lawson LA, Gibson GA, Steinberg MA, MacGregor RR. Vancomycin concentrations in infected and noninfected human bone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;9:1320–1322. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.9.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guiboux JP, Cantor JB, Small SD, Zervos M, Herkowitz HN. The effect of prophylactic antibiotics on iatrogenic intervertebral disc infections: a rabbit model. Spine. 1995;6:685–688. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199503150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hadjipavlou AG, Mader JT, Necessary JT, Muffoletto AJ. Hematogenous pyogenic spinal infections and their surgical management. Spine. 2000;25:1668–1679. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honeybourne D, Tobin C, Jevons G, Andrews J, Wise R. Intrapulmonary penetration of linezolid. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;6:1431–1434. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson KD, Johnston DW. Orthopedic experience with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus during a hospital epidemic. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;212:281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lovering AM, Zhang J, Bannister GC, Lankester BJ, Brown JH, Narendra G, MacGowan AP. Penetration of linezolid into bone, fat, muscle and haematoma of patients undergoing routine hip replacement. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;1:73–77. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manfredi R, Sabbatani S, Chiodo F. Severe staphylococcal knee arthritis responding favourably to linezolid, after glycopeptide-rifampicin failure: a case report and literature review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;6–7:513–517. doi: 10.1080/00365540510036589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massias L, Dubois C, de Lentdecker P, Brodaty O, Fischler M, Farinotti R. Penetration of vancomycin in uninfected sternal bone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;11:2539–2541. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.11.2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McHenry MC, Easley KA, Locker GA. Vertebral osteomyelitis: long-term outcome for 253 patients from 7 Cleveland-area hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;10:1342–1350. doi: 10.1086/340102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng GW, Stryd RP, Murata S, Igarashi M, Chiba K, Aoyama H, Aoyama M, Zenki T, Ozawa N. Determination of linezolid in plasma by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1999;1–2:65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0731-7085(98)00310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rana B, Butcher I, Grigoris P, Murnaghan C, Seaton RA, Tobin CM. Linezolid penetration into osteo-articular tissues. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;5:747–750. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayner CR, Baddour LM, Birmingham MC, Norden C, Meagher AK, Schentag JJ (2004) Linezolid in the treatment of osteomyelitis: results of compassionate use experience. Infection 1:8–14. doi:10.1007/s15010-004-3029-9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Rezai AR, Woo HH, Errico TJ, Cooper PR. Contemporary management of spinal osteomyelitis. Neurosurgery. 1999;5:1018–1025. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199905000-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley LH, Banovac K, 3rd, Martinez OV, Eismont FJ. Tissue distribution of antibiotics in the intervertebral disc. Spine. 1994;23:2619–2625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scuderi GJ, Greenberg SS, Banovac K, Martinez OV, Eismont FJ. Penetration of glycopeptide antibiotics in nucleus pulposus. Spine. 1993;14:2039–2042. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199310001-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Slatter JG, Adams LA, Bush EC, Chiba K, Daley-Yates PT, Feenstra KL, Koike S, Ozawa N, Peng GW, Sams JP, Schuette MR, Yamazaki S. Pharmacokinetics, toxicokinetics, distribution, metabolism and excretion of linezolid in mouse, rat and dog. Xenobiotica. 2002;10:907–924. doi: 10.1080/00498250210158249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Srinivasan A, Dick JD, Perl TM. Vancomycin resistance in staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;3:430–438. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.3.430-438.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tobin CM, Sunderland J, White LO, MacGowan AP. A simple, isocratic high-performance liquid chromatography assay for linezolid in human serum. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;5:605–608. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urban JP, Smith S, Fairbank JC. Nutrition of the intervertebral disc. Spine. 2004;23:2700–2709. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000146499.97948.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]