INTRODUCTION

Recent surveys estimate that almost 30% of American and Canadian medical students gain work experience abroad during their 4 years of medical school (1), and many experts expect that number to increase in the future (1,2). However, little research exists regarding the ethical consequences of such experiences, or on the necessary training needed to prepare students for global health work (3,4).

The ever increasing interest in working abroad among medical students begets implementation of a formal global health curriculum in medical schools in order to adequately prepare students for these endeavors. The need for such education is well documented in a body of research and surveys (1-6). Nonetheless, there is almost no specific information as to what the content of such an education should entail (6,7). This void is most strongly felt in the realm of global health ethics, especially as it relates to the responsibilities, training, and goals of students involved in projects in low resource settings. A research-based and academically informed framework for the development of global health ethics principles is urgently needed.

This paper reviews the literature on ethical education in global health and describes how the small body of research is being used to direct the first evidence-driven Pre-departure Global Health Training Institute offered by a Canadian medical faculty in Ottawa.

DEFINITION OF GLOBAL HEALTH AND GLOBAL HEALTH ETHICS

The Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, a US national advisory body, comprehensively defines global health in the following manner: “Global health is the goal of improving health for all people in all nations by promoting wellness and eliminating avoidable disease, disabilities, and deaths. It can be attained by combining population-based health promotion and disease prevention measures with individual-level clinical care. This ambitious endeavor calls for an understanding of health determinants, practices, and solutions, as well as basic and applied research on disease and disability, including their risk factors” (8).

It is apparent that the context of global health work extends beyond the conventional concept of relief or aid missions abroad, and includes any type of work in lowresource settings aimed at improving the quality of life of the individuals or the population at hand. In this paper, an individual partaking in any type of activity in the context of the above definition is considered to be participating in a global health experience.

Students engaging in global health projects often have altruistic motives for doing so. However, global health experiences are frequently overall more beneficial to the student than the target population. Furthermore, the risks to students, patients, and the communities in which these experiences occur are difficult to ascertain and even more challenging to prevent or minimize without a form of pre-departure supervision or training. Finally, without training in the use of a framework with which to assess the validity and ethical principles of a project, seemingly benevolent projects can have detrimental consequences not only on the student but also on patients and their communities. It is then the role of global health ethics to examine the underlying principles of global health and how they relate to accepted standards of social or professional behavior, beyond the first principle of the medical oath, “first do no harm”. A lack of a workable definition of global health ethics highlights the complexity of the issue and makes the case for more research to be conducted on the topic.

WHY GLOBAL HEALTH EDUCATION?

The primary responsibility of medical schools is to train medical students to become competent clinicians, largely emphasizing professional ethics and patient safety. In Canada, much of this competency is defined around the CanMEDS® roles as described in the CanMEDS® project (9). The CanMEDS® project is an initiative driven by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada and it aims to identify a series of skill and attitude-based competencies that an effective physician should acquire and develop during their career. Many of the roles identified by the project (Professional, Communicator, Collaborator, Health Advocate, Scholar, and Manager) are based on a solid training that includes discourse in Canadian medical law and medical ethics within the context of this law. Although important, this training may not be as applicable to resource poor countries, because these may have a distinct political, economic, legal and social make-up (10). Medical students and inexperienced professionals choosing to do clinical or health care work abroad are bound to find themselves facing unique challenges (10,11).

However, such challenges are not exclusive to international work. In today’s increasingly interconnected world, global health education has become an important aspect of a physician’s clinical competency in his home country (6,7,12). Immigrants and refugees comprise an increasingly greater share of the patient population in Canada, as approximately 20% of the Canadian population is foreign born (13). Furthermore, most new immigrants to Canada arrive from what are considered “developing nations” (13). Diseases can penetrate borders at new rates with significant repercussions, and an appreciation of tropical medicine and foreign infections is becoming ever more important (3,4). A personal history of conflict, human rights violations, or resource disparity continue to cause poor health among many patients within Canada, and thus physicians need to have a solid understanding of how such issues play a role in health (14). These new challenges outline the importance of global health education as a necessary tool for good health care delivery, both abroad and in Canada.

THE GLOBAL HEALTH CURRICULUM: A VOID IN EVIDENCE-BASED CONTENT

Recent research published in The Lancet, New England Journal of Medicine, British Medical Journal, and the Canadian Medical Association Journal has established the role of global health in the education of modern physicians (5-7,9,10). This paper sought to reinforce the idea that the content of global health curricula should be based on strong empirical evidence from research, and as such, more investigation is needed in this area.

In 2006 the Global Health Education Consortium (GHEC), in partnership with the US branches of the International Federation of Medical Students Association (IFMSA-USA and AMSA), produced a guide for global health curriculum development for implementation by Faculties of Medicine (15). This document summarizes the need for global health curriculum, and recommends the incorporation of two educational themes: determinants of health and cultural sensitivity (15). Though it lays out a generalized strategy for implementation, very little guidance is provided on the content of the proposed curriculum. More importantly, no attempt is made to classify the content into educational themes.

In turn, the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC), the main accrediting body for medical school curricula in Canada, in partnership with the Canadian Federation of Medical Students Global Health Program (CFMS-GHP), also developed a template for national guidelines for pre-departure training within Canadian medical school curricula (12). This document recommends guidelines for the curriculum content as well as suggestions on implementation. A noteworthy addition by the AFMC is the identification of core competencies, including personal health, travel safety, cultural awareness, language competencies, ethical considerations, and recommendations and resources for implementation (16). Despite the great organizational benefit to such a document, it remains broad and is the product of consensus. Therefore, it is not strictly evidenced-based, largely due to the absence of such empirical research in the literature.

The research void is most notable in the realm of global health ethics. Work conducted to date has focused extensively on a description of what constitutes ethical practices (17-19). Most of the research has adopted a philosophical perspective, focusing on examples such as the ethics of pharmaceutical practices and developmental and aid work (11,19-22). These topics largely reflect the dilemmas faced by institutions operating on an organizational level, leaving out important quandaries that individuals, such as medical students, may face. Thus, it is important for an ethical framework to exist within which the individual can begin the process of ethical assessment (11,23). Such a framework would allow individuals with no prior experience in the field, as well as veteran workers to develop a strategy for reflecting on ethical dilemmas.

One successful tool to date has been an on-line forum for debriefing created by the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics. Called “Virtual Mentor”, the project consists of a series of letters and articles largely written by students wishing to recount the dilemmas they faced during their international work (24-26). After a student’s contribution, input is given by a faculty member or professional with extensive experience in the area. The differences in reasoning and discussions between students and their Mentor are effective in providing readers with various approaches to tackling the concepts of ethical development. Arguably the best utility of this series is the insight that stands to be gained into potential strategies for analyzing complex issues. The main shortfall of the series is that it focuses on organizational ethics with themes such as ethical pharmaceutical practices (23), fair distribution of medicines while on missions (23), and building effective partnerships in the field (23,27,28). Although such themes are important for students to examine, it is just as important to engage in a model of ethical study focusing on defining the student’s role individually. Furthermore, the series does not attempt to recommend a framework for ethical education in global health, but does reiterate and demonstrate its importance (26).

Andrew Pinto wrote a landmark paper on the issue of ethical training in global health, in which he argues that global health work introduces dilemmas distinct from those faced in one’s own country (10). As the nature of these dilemmas is often unpredictable, Pinto attempts to define a series of ubiquitous ethical principles. Pinto maintains that a foundation of global health ethics borrows much from public health, sociology, epidemiology, and anthropology and a proper ethical assessment of any global health experience therefore requires knowledge of those fields. Within this context, Pinto indirectly classifies global health knowledge into the academic and the ethical. The former is based on a concrete discussion of academic principles of global health, while the latter seeks to lay a framework for ethical discussion in global health by classifying the discourse into four major themes: humility, introspection, solidarity, and social justice.

Pinto’s paper is effective in creating a framework of principles that can be applied to ethical dilemmas. However, very little information is based on empirical evidence, but rather on a theoretical discussion of what is ethical. Many of the principles are derived from works and studies that have not been tested or generated through surveys of individuals working in the field. It is not known whether once applied in practice, these principles will generate a more favorable outcome for the student and the population.

An innovative study by Petrosoniak & McCarthy in 2008 attempted an evidence-based approach in the field of global health ethics (29). Using a needs-based assessment survey, the researchers tried to determine the building blocks of a global health curriculum, including education on global health ethics. Individuals with extensive global health experience were interviewed regarding what they deemed to be the most important aspects of adequate preparation for global health work. Participants were asked to identify obstacles they met during their work and how these could have been avoided by pre-departure training; ethical conflicts they encountered and whether or not they were prepared to handle them; and to assess the effect and measurable outcomes of their work, on the local population as well as on themselves. Preliminary results indicate a consistent response pattern from all participants, emphasizing the need for objective training in global health principles. Many students found themselves in ethical conflicts during their global health electives, providing examples such as difficulties with accepting limited resource allocation, specific patient management concerns, concerns about conduct of clinical research and requirements to undertake activities beyond their scope of competence related to their training. It was clear from the responses of trainees as well as supervising faculty that dealing with ethical conflicts occurring in a global context differ significantly from the ethical framework that they had learned in Canada. Most felt that more training related to ethics in the global health context would better prepare them for their experience.

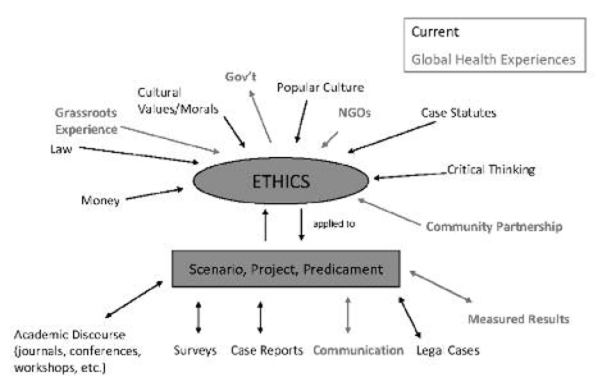

Currently, students are able to refer to general ethical guidelines, such as the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and the International Code of Medical Ethics. In figure 1, we illustrate a model used to generate such universal medical ethical standards, and additional items which make this model applicable to global health ethics. This figure also serves as a good preliminary model to be applied to an ethical dilemma arising in global health work. Items in black represent traditional elements used in the development of current medical ethics. Items in red are specific to ethical dilemmas in low resource settings.

Figure 1: Model of generation of ethical standards. In customary medical ethics, legal cases, surveys and previous case reports inform conduct in an ethical dilemmas. In a global health or low resource setting, additional considerations (red) are needed in order to develop a series of ethically valid principles.

To illustrate how such a framework may be employed, consider the case of a student working for a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that provides essential health care services to a low resource community. The NGO distributes indispensable resources to select individuals under a strict set of rules, without consultation with community members. This ultimately creates animosity amongst individuals and a rift in the community structure. Does the student continue to provide essential services to those in need by continuing to work with the NGO, or does she protest unfair and unequal resource distribution of resources by terminating her work with the NGO? The ethical framework introduced below identifies the resources and principles available to students to begin the discourse necessary for answering such questions.

FROM RESEARCH TO CURRICULUM: THE CASE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA’S PREDEPARTURE TRAINING INSTITUTE

In response to the large-scale need for a global health curriculum and pre-departure preparedness training, the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Medicine students and faculty have launched a pilot global health training institute. The aim of the institute is to provide students interested in global health work with a set of aptitudes, tools and introspective methods within which they can frame their international experience.

Set out over the course of 4 days and anchored in principles of problem-based learning and didactic lectures, the institute will cover several themes by experts in their respective fields. The content of the institute is based on the aforementioned work by Petrosoniak & McCarthy (29) and existing research, and was organized into three components: knowledge, attitudes and practice/skills. In Table 1 we outline the framework used to guide the institute curriculum development.

Table 1: Framework used to guide the content of a global health curriculum employed at a Pre-departure Training Institute at University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine in 2008. The framework is largely guided by the results of the McCarthy and Petrosoniak needs assessment survey (2008), and existing research in the field.

| Knowledge | Attitudes | Practice/Skills |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The first day is an introduction to global health, emphasizing the social determinants of health, indicators of health, key players in health policy and development, access to essential medicines and migrant health. The second day focuses on global health ethics and patient safety. It addresses the assessment of global health projects, exploring and understanding one’s own motivations, goals and responsibilities, as well as measuring impacts on the local population. The third day deals with practical aspects of global health work, addressing pre-departure preparation, personal safety, tropical diseases, proper cultural, political and linguistic preparation, and personal preparedness. The fourth day brings the lessons of global health back to Canada by looking at vulnerable populations in our own country: Aboriginals, homeless, sexually diverse and intravenous drug users.

In addition to the didactic lectures, students have the opportunity to work through problem-based cases with experienced experts in the field of global health. The cases contain dilemmas of just resource distribution, applying principles of social justice and equality, and understanding one’s role in a global health project. As an example, one case students are asked to work through is that of Jo, a second year medical student participating in a surgery elective in a rural African village (30). Before departing, Jo is offered recently expired medications to take to the host community, and debates purchasing personal protective equipment and HIV prophylactic medications as none are available at the local hospital. Once engaged in the elective, Jo becomes aware of resource disparities apparent by standards of patient care, and of her inability as a trainee to affect them. In addition, distribution of human resources becomes problematic as Jo’s preceptor is keen to teach Jo, neglecting local students and awaiting patients. Under the doctor’s supervision, Jo is allowed to perform a bowel resection, and sustains a needle stick injury. Upon returning home and starting clerkship, Jo is finding it difficult to relate to patients with minor medical issues as a result of being exposed daily to critically ill patients in her host country.

This case illustrates several common ethical scenarios encountered before, during and after a global health experience. The intent of these sessions is to highlight potential obstacles a student may face overseas or locally, and to provide a safe milieu for reflection, guided by expert opinion. Most importantly, they allow students to consider common ethical scenarios encountered during global health work in a model environment, before the consequences of their actions risk having detrimental outcomes.

As an objective means of evaluating the program’s impact, a questionnaire before and after program participation was administered to measure changes in knowledge and attitudes. This questionnaire is currently being assessed and the outcomes will be used to influence next year’s institute.

CONCLUSION

Global health work has been increasing in popularity among health care professionals and students. What in the past was considered to be only an area of special interest has transformed into a respectable and valuable academic discipline. Global health has evolved into a crossroad where public health, globalization, politics and human rights intersect. It is becoming increasingly more important to frame the principles of this discipline as an engaged effort on the part of many interconnected communities, key players, stakeholders, governments, non-governmental organizations, and individuals. As a true multidisciplinary specialty, with the potential to serve communities on a very large scale, global health needs to receive the same empirical attention as any other specialty in medicine, with the same standards of discovery, discussion, and implementation.

However, this call to action would be incomplete without addressing the need for integration of global health ethics into any pre-departure training or global health course. In Figure 1, we outline components of an ethical assessment framework specific to global health work. Furthermore, in Table 1 we outline a framework for development of such a curriculum, guided by the results of the needs assessment survey conducted by McCarthy and Petrosoniak (2008) (29) and implemented in University of Ottawa’s Pre-departure Training Institute in 2008.

Any career in global health is bound to face ethical dilemmas, many of which will pose significant challenges to patients and communities. Achieving the best possible outcome requires having the necessary knowledge, attitudes and skill sets around global health and global health ethics, which allows for the generation of sustainable solutions and compromises. Any student wanting to excel in this field and wanting to minimize harm to themselves, partners, global health communities and patients needs a solid grounding in the principles of global health and global health ethics. Faculties of Medicine in Canada have a responsibility to ensure their students receive this important education.

REFERENCES

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges, authors. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire, All Schools Report. 2006. Available at: http://www.aamc.org/data/gq/allschoolhsreports/2006.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2008.

- 2.Wilson CL, Pust RE. Why teach international health? A view from the more developed part of the world. Educ Health. 1999;12:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global Health in Medical Education: A Call for More Training and Opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82(3):226–230. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180305cf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bissonette R, Route C. The education effect of clinical rotations in non-industrialized countries. Fam Med. 1994;26:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godkin MA, Savageau JA. The effect of a global multiculturalism track on cultural competence of preclinical medical students. Fam Med. 2001;33:178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yudkin JS, Bayley O, Elnour S, Willott C, Miranda JJ. Introducing medical students to global health issues: a bachelor of science degree in International health. Lancet. 2003;362:822–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haq C, Rothenberg D, Gjerde C, et al. New world views: preparing physicians in training for global health work. Fam Med. 2000;32:566–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Committee on the U.S. Commitment to Global Health, authors. Institute of Medicine of National Acedemies. The U.S. Commitment to Global Health: Recommendations for the Public and Private Sectors. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12642.html. Accessed May 23, 2009.

- 9. CanMEDS Roles® Project. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 2005. Available at: ( http://www.meds.queensu.ca/medicine/obgyn/pdf/CanMEDS.overview.pdf) Accessed March 12, 2008.

- 10.Pinto AD, Upshur RE. Global health ethics for students. Developing World Bioetics. 2007 Jul 26; doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00209.x. Published article online: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Izadnegahdar R, Correia S, Ohata b, et al. Global Health in Canadian Medical Education: Current Practices and Opportunities. Acad Med. 2008;83(2):192–198. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31816095cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.AFMC Global Health Resource Group and CFMS Global Health Program. Preparing medical students for electives in lowresource settings. 2008 May

- 13.Census of Canada. Statistics Canada. 2006 Available at: ( http://www12.statcan.ca/english/ census/index.cfm). Accessed April 4, 2008.

- 14.Institute of Medicine, authors. Microbial Threats to Health: Emergence, Detection, and Response. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Developing Global Health Curricula: A collaboration of AMSA, GHEC, IFMSA-USA, AND R4WH, authors. A guidebook for US medical schools. 2006. GHEC Library of Resources. Available at: ( http://www.globalhealth-ec.org/GHEC/Resources/resources.htm). Accessed February 15, 2008.

- 16.AFMC Resource Group on Global Health, authors. Creating Global Health Curricula for Canadian Medical Students. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K. Globalization and Health: An Introduction. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimball AM, Arima Y, Hodges JR. Trade related infections: farther, faster, quieter. Global Health. 2005;1:3–3. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edejer T. North-South Research Partnerships: The Ethics of Carrying out Research in Developing Countries. BMJ. 1999;319:438–441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7207.438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78:342–347. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda JJ, Yudkin JS, Willow C. International health electives: four years of experience. Trav Med and Inf Dis. 2005;3:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boelen C. Prospects for change in medical education in the twenty-first century. Acad Med. 1995;70:S21–S28. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199507000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alcauskus MP. From medical school to mission: the ethics of international medical volunteerism. AMA J Ethics. 2006;8(12):797–800. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.fred1-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Currie R, Pust R. Pragmatic principles of pharmaceutical donation. AMA J Ethics. 2006;8(12):801–807. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.ccas1-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruxin J. Policy forum: How has the Global Fund affected the fight against AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria? AMA J Ethics. 2006;8(12):839–842. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.pfor1-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kasten J. Medical humanities: Albert Schweitzer: His experience and example. AMA J Ethics. 2006;8(12):859–862. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.mhum1-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.List JM. The educational value of international electives. AMA J Ethics. 2006;8(12):818–825. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.medu1-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abbasi NR, Godkin M. Limits on student participation in patient care in foreign medical brigades. AMA J Ethics. 2006;8(12):808–813. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.ccas2-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olakanmi O, Perry PA. Medical volunteerism in Africa: an historical sketch. AMA J Ethics. 2006;8(12):863–870. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2006.8.12.mhst1-0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrosoniak A, McCarthy A, Varpio L. Global Health Curriculum: Meeting needs at the undergraduate and postgraduate level. Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada (AFMC) Canadian Conference on Medical Education; Annual Meeting; May 2008; Montreal, QC. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saciragic L, Hamadani F, Petrosoniak A, McCarthy AE. University of Ottawa Pre-Departure Institute PBL student manual. 2008. [Google Scholar]