Abstract

Many ultrasound studies involve the use of tissue-mimicking materials to research phenomena in-vitro and predict in-vivo bioeffects. We have developed a tissue phantom to study cavitation-induced damage to tissue. The phantom consists of red blood cells suspended in an agarose hydrogel. The acoustic and mechanical properties of the gel phantom were found to be similar to soft tissue properties. The phantom’s response to cavitation was evaluated using histotripsy. Histotripsy causes breakdown of tissue structures by generation of controlled cavitation using short, focused, high-intensity ultrasound pulses. Histotripsy lesions were generated in the phantom and kidney tissue using a spherically focused 1-MHz transducer generating 15 cycle pulses at a pulse repetition frequency of 100 Hz with a peak negative pressure of 14 MPa. Damage appeared clearly as increased optical transparency of the phantom due to rupture of individual red blood cells. The morphology of lesions generated in the phantom was very similar to that generated in kidney tissue, at both macroscopic and cellular levels. Additionally, lesions in the phantom could be visualized as hypoechoic regions on a B-Mode ultrasound image, similar to histotripsy lesions in tissue. High speed imaging of the optically-transparent phantom was used to show that damage coincides with the presence of cavitation. These results indicate that the phantom can accurately mimic the response of soft tissue to cavitation and provide a useful tool for studying damage induced by acoustic cavitation.

Keywords: Tissue phantom, cavitation, ultrasound therapy, histotripsy

INTRODUCTION

Tissue-mimicking phantoms are commonly used in therapeutic ultrasound for dosimetry (Arora et al. 2005; Canney et al. 2008), in-vitro research (Tu et al. 2007), transducer characterization (Lierke and Hemsel 2006), and quality assurance. A number of phantoms have been used to simulate thermal lesion formation caused by ultrasound-induced heating in high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) (Divkovic et al. 2007; Lafon et al. 2005; Lafon et al. 2006,). While these can accurately mimic the response of soft tissues to heating, they are unable to visualize or quantify mechanical damage due to acoustic cavitation caused by high-intensity ultrasound. The lysis of cells due to cavitation has been known for some time. Hughes and Nyborg (1962) demonstrated disruption of cells was specifically caused by the presence of cavitation from gas-filled holes in a brass plate driven at 20 kHz. Other in-vitro tests are often performed with cells in suspension (Miller et al. 1991; Williams et al. 1999), cell layers (Brayman et al. 1999; Sondén et al. 2002), and immobilized in tissue mimicking materials for study of lithotripsy (Brümmer et al. 1989) and HIFU gene activation (Liu and Zhong 2006). Cavitation-enhanced heating has also been studied in gel phantoms (Holt and Roy 2001; Liu et al. 2006), but the mechanical effects of cavitation were not measured.

A tissue phantom for measurement of mechanical cavitation damage would be valuable in both ultrasound imaging and therapy. Guidelines for limiting the output of diagnostic transducers are based on acoustic parameters which indicate the likelihood of generating cavitation, such as peak rarefractional pressure, transducer frequency, and pulse length. A phantom could verify whether a given transducer and set of acoustic parameters are capable of causing such effects. For ultrasound therapy, it may be useful for providing a quantitative metric for the extent and pattern of unintended tissue damage (as in the case of lithotripsy and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy) surrounding the focus. Finally, it is beneficial for studying intentionally-induced cavitation damage, as such with histotripsy, which relies on cavitation to cause mechanical disintegration of tissue structures. Previously, studies of histotripsy have been performed in ex-vivo tissue (Kieran et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2009) or in-vivo (Hall et al. 2008). However, a tissue phantom is capable of providing instant visual feedback, observation of cavitation-cell interaction, and a record of the accumulated damage immediately, while tissue samples require preparation and expensive histology to properly examine the morphology of lesions induced.

A tissue phantom for measuring cavitation induced damage should contain a visual marker to show the location and extent of mechanical damage. Therefore, it is important that the phantom is as optically transparent as possible, so that the markers indicating damage can be located by either gross examination or microscopy. Additionally, this property also allows for direct observation of cavitation-induced damage by high-speed imaging during insonation, which cannot be performed in ex-vivo tissue. In this study, we used red blood cells embedded within an agarose hydrogel to act as the visual indicator. If an appropriate cell density is chosen, the phantom will scatter and absorb light, making it appear translucent red. Upon rupturing the membranes of the red blood cells, the area will become uniform, no longer scattering light, and the phantom will locally appear more transparent. Previous work has demonstrated the sensitivity of red blood cells to even modest cavitation activity (Williams and Miller 1980). Nyborg and Miller (1982), showed that red blood cells specifically in the vicinity of cavitation bubbles on a membrane were subjected to high shear stress due to microstreaming, a cause of lysis. Similarly, we found that the lysis of red cells in the phantom is only induced when and where cavitation is generated by ultrasound.

In addition to being sensitive to cavitation damage, the phantom should ideally possess mechanical and acoustic properties similar to soft tissues (e.g. kidney cortex, liver, or prostate). The density, sound speed, and ultrasonic attenuation must be similar to tissue to appropriately simulate ultrasound imaging used for therapy guidance. Mechanical properties, such as elastic (Young’s) modulus, must also be in the range of soft tissues. Cavitation models suggest that inertial cavitation can be suppressed with increasing elastic modulus (Yang and Church 2005). Cavitation activity will in turn determine whether there is sufficient cell deformation to rupture cell membranes and incite irreversible tissue damage (Lokhandwalla and Sturtevant 2001). Finally, the gel should be relatively simple and inexpensive to prepare, as one purpose is to avoid the costs associated with using ex-vivo tissue and histology.

Although the phantom has a number of potential applications, this work focuses on the cavitation lesions induced by histotripsy. Histotripsy is a non-invasive therapy which uses short, high-pressure ultrasound pulses to mechanically fractionate tissue structures into fine debris. The destruction of tissue has been found to only occur when the ultrasound induces a cavitation bubble cloud at the focus of the therapy transducer (Xu et al. 2005). The bubble cloud at the focus is easily visualized as a dynamic, highly echoic region on a B-Mode image at the focus of the transducer, which provides an indication of where ablation is occurring. Furthermore, histotripsy causes disruption of individual cells, creating small debris fragments which do not scatter ultrasound as effectively as intact cell structures (Hall et al. 2007). The resulting lesions appear as hypoechoic regions compared with intact tissue, which can be used to evaluate the progression of treatment. Thus, ultrasound imaging can be used for targeting and feedback to determine when tissue ablation has occurred.

In this paper, we investigate the performance of the red blood cell phantom as a cavitation damage indicator. The acoustic and mechanical properties of the gel phantom were measured. Histotripsy lesions were generated in ex-vivo kidney tissue and the gel phantom to evaluate the phantom’s ability to mimic actual cavitation-induced lesions. Lesion appearance on B-Mode images in tissue and the phantom was also compared. Finally, high-speed imaging was performed to visualize cavitation activity in the phantom and verify the correlation between cavitation activity and lesion formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Phantom Preparation

The protocols described in this paper have been approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA). Agarose gel phantoms were prepared using a mixture of Type VII agarose powder (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and canine red blood cells in 0.9% isotonic saline. Fresh canine blood was obtained from adult research subjects in an unrelated study and added to an anticoagulant solution of citrate-phosphate-dextrose (CPD) (C1765, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) with a ratio of 1 mL CPD to 9 mL blood. Whole blood was separated in a centrifuge at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes. The plasma and white buffy coat were removed, and the red blood cells (RBCs) were saved for addition to the phantom. Agarose was slowly combined with saline while stirring at 20°C (1.5% w/v agarose/saline), forming a translucent solution. The solution was heated in a microwave oven for 30 seconds and then stirred. Heating in 30 second intervals and stirring was repeated until the solution turned entirely transparent. The solution was placed under a partial vacuum of 20.5 psi for 30 minutes to degas the mixture. After removing the mixture from vacuum, a layer of agarose was poured into a rectangular polycarbonate housing to fill half of it with agarose. The housing was placed in a refrigerator at 4°C to allow the agarose to cool and solidify. The remaining agarose solution was kept at 45°C for 1 hour. A small amount of agarose solution was mixed with the RBCs (5% RBCs v/v). The frame with solidified agarose was removed from refrigeration and a thin layer of the RBC-agarose solution was poured onto the gel surface to allow the entire surface to coat in a layer ~500 μm thickness. After 5 minutes, the RBC/agarose layer was solidified, and the remaining agarose solution without RBCs was poured to completely fill the frame. This procedure created a thin layer of red blood cells suspended in the center of the agarose phantom. A solid RBC-agarose phantom can also be prepared with some loss of optical transparency. However, only results from the layered RBC phantom are reported herein.

Measurement of Phantom Properties

Measurements of tissue phantom properties including density, sound speed, attenuation, and elastic (Young’s) modulus were performed. Ten agarose phantom samples were prepared as described above for measurement of properties. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

The density of each sample was characterized by direct measurement of volume and mass on a laboratory balance. Next, the sound speed and attenuation were measured using a broadband pulse technique. A 13 mm aperture 3.5 MHz unfocused transducer (Aerotech Laboratories, Lewistown, PA, USA) was placed in a degassed water tank, and a hydrophone (HGL-0085, ONDA Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was positioned facing the transducer approximately 7 cm from the source. Care was taken during experiment not to disturb the source and hydrophone in order to maintain fixed distance measurement. An insertion method such as that used here produces smaller errors due to diffraction than variable distance measurements, and diffraction can generally be neglected when the media have approximately the same speed of sound (Xu and Kaufman 1993). A broadband pulse with center frequency of 3.5 MHz was first transmitted through water. Next, the tissue phantom thickness was measured and placed in the path of the source, and the same pulse was transmitted. The attenuation coefficient was measured by calculated using the method outlined in (He 1999). The sound speed was determined by a time lag of the peak in cross-correlation of the acoustic signals with and without the sample in the path. The acoustic impedance was calculated directly from the product of density and sound speed.

Elastic modulus was measured using an elastometer constructed using the same method outlined in (Egorov et al. 2008). A motorized positioner was used to hold a 6.2 mm diameter aluminum rod with a hemispherical end on the sample placed on a laboratory balance. The rod was brought into contact with the gel, and pressed by the positioner into the gel a known distance. The scale reading was recorded to determine the force on the phantom. Several positions and force readings were recorded to obtain a plot of stress vs. strain. The Young’s modulus of the phantom was determined by a linear fit to the stress-strain curve.

Kidney Tissue Preparation

Histotripsy lesions were generated in the RBC phantom and ex-vivo porcine kidney to compare the morphology and progression of lesion formation in each sample. Fresh tissue was obtained from a local abattoir and placed in 0.9% saline solution at room temperature. All experiments were conducted within 6 hours of harvest.

Histotripsy Lesion Generation

A spherically-focused piezocomposite transducer (Imasonic, Besancon, France) with a 10 cm diameter and 9 cm focal length was used as a therapy transducer. The transducer operates at 1 MHz, and is driven by a class D amplifier with matching network developed in our lab. The transducer was positioned in a tank of degassed, filtered water, and the focus was aligned to the cortex of the kidney sample in a plastic bag filled with saline submerged in the tank. Ultrasound was fired at a 3×3 grid of points sequentially, with 2 mm spacing between points. The total exposure time at each point was 1500 pulses. The parameters used were 100 Hz, 15 cycles. This pattern was chosen over single spot treatments so that lesions were more easily located in tissue for histological sectioning. After treatment, the tissue was removed from the bag and rinsed with fresh saline, then placed in a 10% phosphate-buffered formaldehyde solution (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). After 7 days, the kidney was sectioned and Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained histology slides were made for each spot treated in the kidneys. The RBC phantom was immediately removed after treatment and the RBC layer was photographed.

To visualize the cross-sectional profile of tissue damage in the phantom, the transducer was used to deliver the same acoustic parameters to single focal spots in the phantom. In this case, the RBC layer was aligned perpendicular to the focal zone. After sonication of a spot, the focus was moved to a new location 1 cm away, and the exposure was repeated.

Images of lesions in tissue and the phantom were analyzed in MATLAB to determine the dimensions of the focal lesions from photographs of the phantom and histology slides for the kidneys.

Ultrasound imaging of lesions

B-Mode ultrasound images of the lesions in the phantom and tissue were recorded before and after treatment of kidneys and phantoms. An ultrasound imager with a 10 MHz linear probe (10L probe, Logiq 9, General Electric, Fairfield, CT, USA) was used to acquire images by placing the probe in contact with the tissue or phantom. For the phantom, the linear probe was oriented to acquire an image parallel with the RBC layer in the gel and the B-Mode gain was adjusted to observe the speckle pattern in the gel or tissue. Axial profiles of the lesions made by the therapy transducer were also obtained.

Correlation of cavitation with lesions in RBC phantom

High-speed imaging of the phantom was performed while applying single histotripsy pulses to the phantom in a tank of degassed, filtered water. The therapy transducer described above was used to generate cavitation clouds in the phantom. A high speed camera (SIM02, Specialised Imaging Ltd., Hertfordshire, UK) was used to obtain high speed images of the cavitation cloud in the phantom placed in the water tank at the focus of the transducer (Figure 1). The field of view was chosen such that the entire extent of the bubble cloud at the focus could be observed. The end of a fiber optic bundle coupled to a flash lamp was positioned behind the RBC phantom to provide backlighting of the phantom during image exposure.

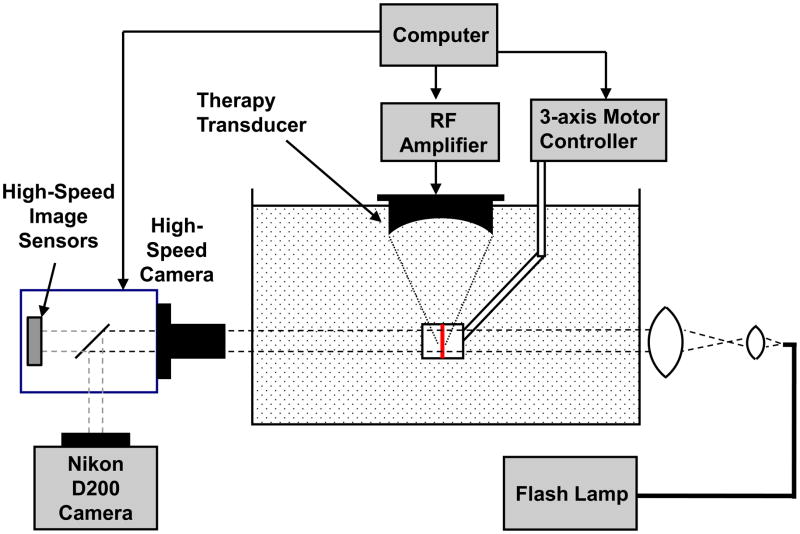

Figure 1.

High speed imaging apparatus used to acquire images prior to, during, and after phantom insonation. The RBC layer of the gel was positioned within the ultrasound focus. The high speed camera was positioned imaging the plane of RBCs, and a flash lamp was used to backlight the phantom. A digital camera was also used to take high-quality images before and after insonation.

The gel phantom was positioned such that the camera was imaging through the plane of RBCs in the phantom, and the ultrasound propagated parallel to this plane and focused within the RBC layer. Prior to ultrasound exposure, an image of the phantom was recorded using a separate digital SLR camera (Nikon D200, Nikon USA, Melville, NY, USA) attached to the optical port of SIM 02 high-speed camera. After the initial image capture, a single, 10-cycle pulse with peak negative pressure of 19 MPa was generated by the therapy transducer, and images were recorded using the high speed camera in a time sequence 160 μs in length starting at the time the first cycle of the ultrasound pulse reached the focus. Another image was recorded 30 seconds after exposure using the digital SLR camera to observe the final phantom appearance. The reason for use of the SLR camera for pictures before and after sonication was to minimize noise so that the two images could be subtracted to obtain a profile of the lesion. While this could also be done with the high-speed camera, the noise due to the camera’s internal image intensifiers was much greater. A new location in the phantom was targeted for each pulse applied.

Images were analyzed using MATLAB software (Mathworks, Natick, MA, USA). The damage profile in the phantom was assessed using the images before and after ultrasound exposure captured by the digital SLR camera. First, the images were cropped to obtain the same field of view as the high-speed camera. Images were converted from color to grayscale, and image intensity in both before and after pictures was normalized such that the background intensity was the same for both pictures. A 3×3 pixel smoothing kernel was applied to reduce noise in the image. Next, the two images were subtracted to obtain the difference between the before and after pictures. Image contrast was then normalized such that the subtracted image spanned the entire 8-bit dynamic range. The image was converted to a binary image using the graythresh function in MATLAB to obtain the threshold level. Each lesion area was identified separately, and areas smaller than 10 pixels were removed as noise.

High speed images of the cavitation cloud were also processed to produce a binary image. A 3×3 pixel smoothing kernel was applied, and then the image was converted to binary using the same technique. Areas of the lesion were identified in the same manner as the lesion images. The overall dimensions and area of the lesions, as well as their locations were compared to the locations and size of the bubble cloud.

RESULTS

Tissue Phantom Properties

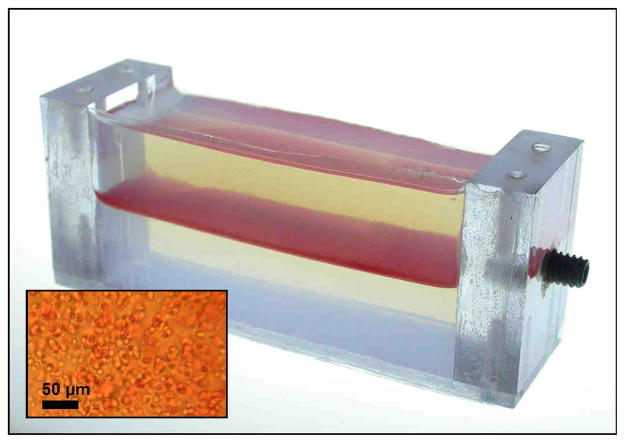

A photograph of an untreated RBC phantom is shown in Figure 2. The phantom is transparent, except for the thin RBC layer in between the two layers of plain agarose. Although several agarose types were tested, Sigma Type VII was chosen because of its low gelling temperature and high clarity. The low gelling temperature allowed the agarose to cool to a temperature where red blood cells would not be lysed while adding to the mixture during preparation. The agarose layers are transparent, while the RBC-agarose mixture appears as a red, translucent layer. Layer thickness or % hematocrit within the RBC layer could be adjusted to achieve sufficient contrast between treated and untreated zones. 5% hematocrit was used for the purpose of these tests. We found the RBCs are not lysed when the phantom is placed in pure water, even for several hours. However, the phantom cannot be left in tap water indefinitely during experiments, as diffusion of water into the agarose will eventually cause hypotonicity of the agarose and cell lysis. Red cell phantoms could be stored in refrigeration at 4°C covered in plastic wrap for 2 weeks without change in appearance.

Figure 2.

A photograph of the cell phantom in a polycarbonate holder. The phantom consists of 3 layers of agarose, with the middle layer containing 5% red blood cells. The insert shows the visual appearance of the red blood cell layer during examination under a microscope.

A total of 10 samples were prepared separately for measurement of the phantom properties. The mean density measured was 1.02 ± 0.016 g/cm3 at 21°C. The sound speed in the samples was 1501 ± 2 m/s, giving an acoustic impedance of 1.53 MRayl. Attenuation measured relative to water in the 8 samples was 0.11 ± 0.017 dB/cm at 1 MHz, and was found to increase nearly linearly with frequency in the range of 1–5 MHz. The mean value for Young’s modulus measured was 62.0 ± 12.1 kPa. The values for Young’s modulus varied significantly from sample to sample. However, the values were within the range measured by others for agarose gels (Normand et al. 2000), and soft tissues (Ophir et al. 2002). A summary of the properties for the phantom, as well as standard values for water at 20°C and soft tissues is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Acoustic and mechanical properties of the tissue phantom measured in this study at 20°C. Reference values for properties from water and soft tissues are also provided.

| Water | Tissue Phantom | Soft Tissues | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m3) | 998 | 1020 | 1050 |

| Sound Speed (m/s) | 1484 | 1501 | 1480–1560 |

| Acoustic Impedance (MRayl) | 1.48 | 1.53 | 1.61 |

| Attenuation (dB/cm/MHz) | 0.0022 | 0.11 (1–5 MHz) | 0.4–0.7 |

| Elasticity (kPa) | - | 62 | 10–30 |

Comparison of Lesions in Phantom and Ex-Vivo Tissue

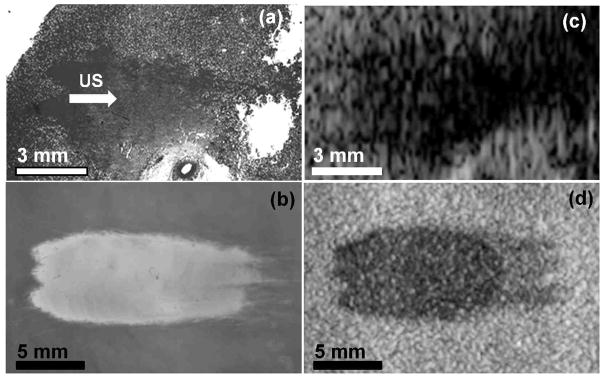

Lesions were generated using identical parameters in both the phantom and ex-vivo kidney and liver tissues. Lesions were induced by scanning a 3 × 3 grid of points with 2 mm spacing and 1500 pulses per point. Therefore, lesions observed in the phantom and tissue histology are an accumulation of damage caused in 9 adjacent focal regions, although only 3 of the foci are in the plane of the RBC layer. The grid scan was used to create larger lesions which would be easily distinguished in tissue. Figures 3a and 3b show photographs of lesions in the phantom and kidney tissue histology.

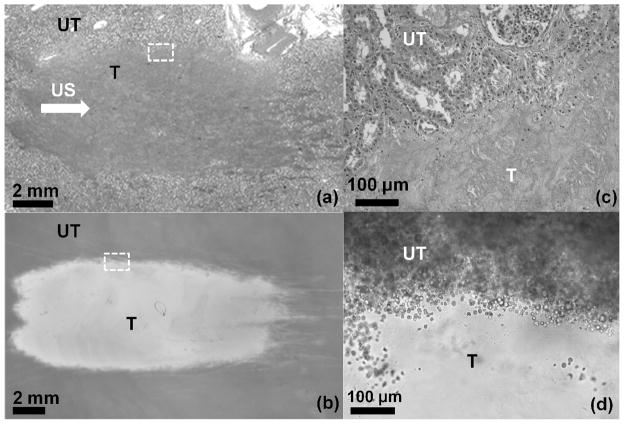

Figure 3.

Images of (a) histology of a lesion generated in ex-vivo kidney using 1500 pulses in 3 adjacent focal spots with 2 mm spacing and (b) a lesion generated in the cell phantom using identical parameters. Ultrasound (US) propagation is from left to right. Lesions in kidney appear as a more homogeneous region due to cell structure disruption, while lesions in the phantom show increased transparency. Magnified images of the boundary between treated (T) and untreated (UT) regions of the lesions in Figure 3a and Figure 3b are also shown in 3c and 3d, respectively. The disrupted zone of the phantom shows virtually no red blood cells remaining, while the region only 50μm from the lesions shows similar appearance to untreated phantom.

A total of 9 lesions were created in the phantom and 8 in the kidney cortex. The average lesion dimensions in the phantom were 18.5 ± 2.0 mm axially and 7.6 ± 0.4 mm laterally. The average dimensions in the kidney tissue were 13.3 ± 3.9 mm axially and 6.8 ± 0.8 mm laterally. In kidney tissue, the axial dimension of the lesion was often limited due to the overlap of the focal volume with parts of the medulla of the kidney. In this area, no tissue disruption was apparent. Therefore, the axial length of the lesion was often shorter than the full focus. Additionally, damage was more difficult to visualize in the tissue than the phantom, in part because of the lack of contrast between the homogenized and intact tissue. The boundaries of the lesion were well defined, with a width of only a few red blood cells between completely disrupted area of the phantom containing no intact cells and the area with similar appearance to untreated phantom (Figures 3c, 3d). This result is consistent with previous studies of histotripsy lesions, where the lesion boundaries were found to be thin enough to bisect individual myocytes (Xu et al. 2009).

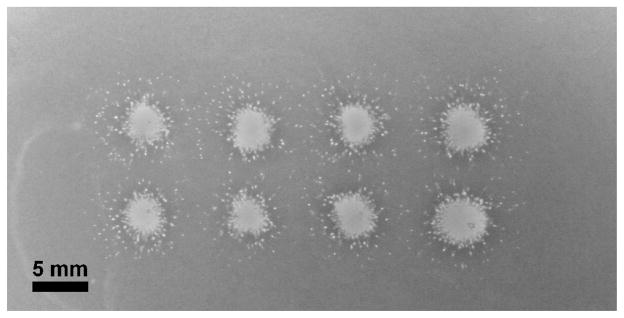

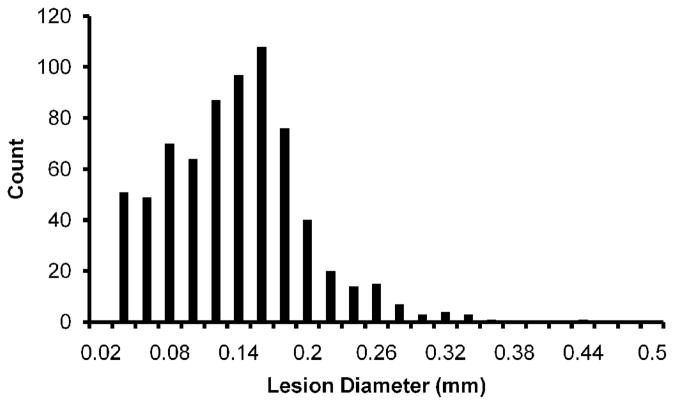

Lesions were also made by applying ultrasound to a single spot through the tissue phantom RBC layer, producing a lateral profile of the cavitation damage. The 8 lesions generated in the phantom were very consistent, with a totally disrupted area at the center surrounded by small circular ‘microlesions’ extending approximately 5 mm from the lesion center (Figure 4). The mean diameter of the main lesion was 3.01 ± 0.15 mm, which is also consistent with the lateral dimension of bubble clouds observed in the gel. The microlesions had a size distribution from 20–440 μm diameter, with a peak in the range from 140–160 μm. Figure 5 shows a histogram for the size distribution of 710 microlesions in the phantom, excluding the main central lesions in 8 separate samples.

Figure 4.

Eight lesions generated in a cell phantom by applying ultrasound perpendicular to the RBC layer. Each lesion is an accumulation of cavitation damage caused by applying 1500 pulses to a single focal spot. The phantom shows a completely disrupted region within the center of the focal zone, and small microlesions surrounding this area.

Figure 5.

Histogram of collateral microlesions’ diameters recorded in the 8 focal spots shown in Figure 4 (not including the central lesion). A local peak is observed at about 150 μm diameter, which corresponds well with single bubbles observed on high speed images of the phantom.

Ultrasound Imaging of Lesions

Images of the phantom treated were recorded using a B-Mode ultrasound imaging probe before and after treatment. The RBC layer appeared as a uniform area with increased speckle vs. the agarose without red blood cells or water. Although the speckle was apparent, higher gain settings on the machine were necessary to achieve equivalent contrast to that in real tissue. Lesions appeared as hypoechoic regions in the RBC layer of the phantom, as is common for histotripsy lesions generated in tissue. Tissue and phantom lesion photographs and their corresponding B-Mode images are shown in Figure 6 for comparison. The size and shape of hypoechoic regions match well with the actual lesion size. The three tails of the treated zone are apparent with a higher degree of echogenicity on the B-Mode image than the upper part of the lesion. Under microscope, some cells are still intact within the lower tails of the lesion. This behavior is also apparent in tissue, where the degree of echogenicity and backscatter can be used as an indicator for treatment progression (Hall et al. 2007).

Figure 6.

Comparison of photographs and B-Mode images of lesions. (a) shows a photograph of kidney lesion histology and (b) is a lesion in the cell phantom. Histotripsy ultrasound (US) propagation is from left to right. The B-Mode image has a hypoechoic appearance similar to that seen for histotripsy lesions in ex-vivo kidney tissue (c). B-Mode image of the phantom lesion is shown in (d).

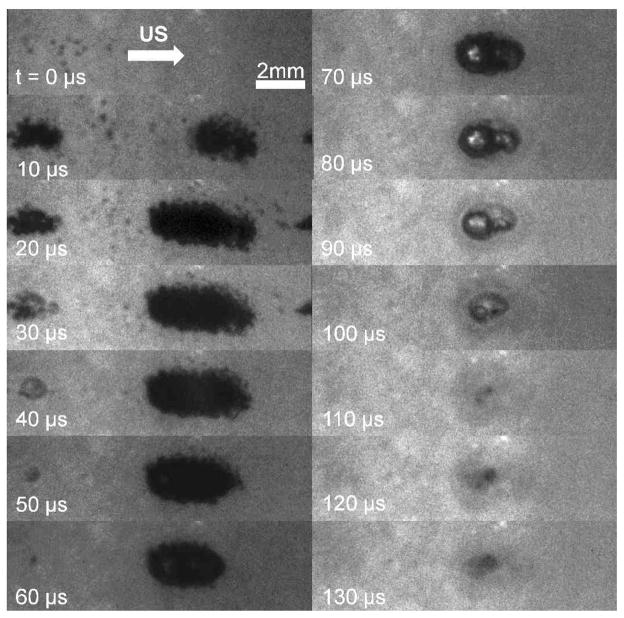

Correlation of Lesions with Cavitation

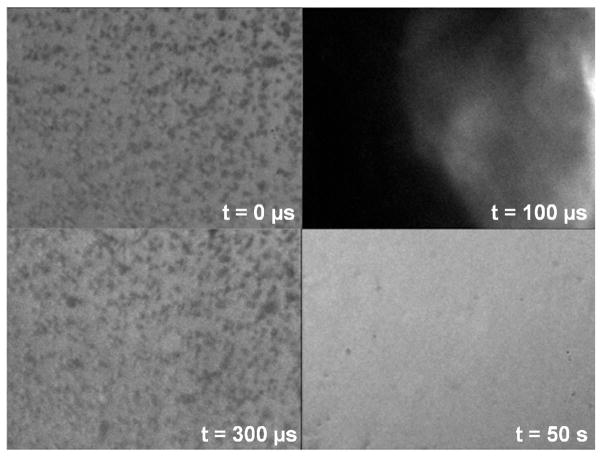

Cavitation clouds and individual cavitation bubbles were observed in the gel phantom during a single ultrasound pulse. Clouds always formed at the center of the transducer focus laterally, with between 1–4 distinct clouds forming during the pulse along the axis of propagation. Smaller single cavitation bubbles were observed in a larger region surrounding the focus during the pulse and for 10–20 μs after the pulse. Clouds formed during ultrasound exposure and then collapsed over a time course of 70–140 μs after the ultrasound pulse had past. Figure 7 shows a sequence of photos captured during a single histotripsy pulse using the high speed camera.

Figure 7.

Images captured by the high-speed camera during a single ultrasound pulse. Ultrasound propagation is from left to right. The pulse arrives on the left at 0 μs and passes through the focus between 0–20 μs. The bubble cloud generated during the pulse then collapses 110 μs after ultrasound exposure.

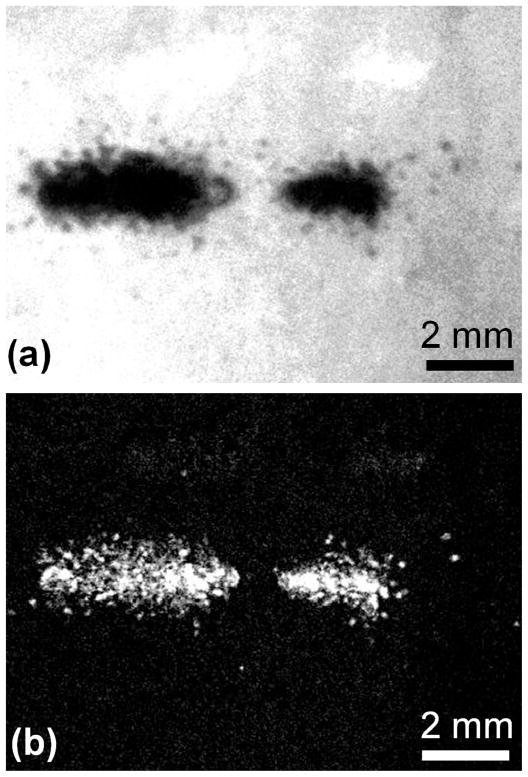

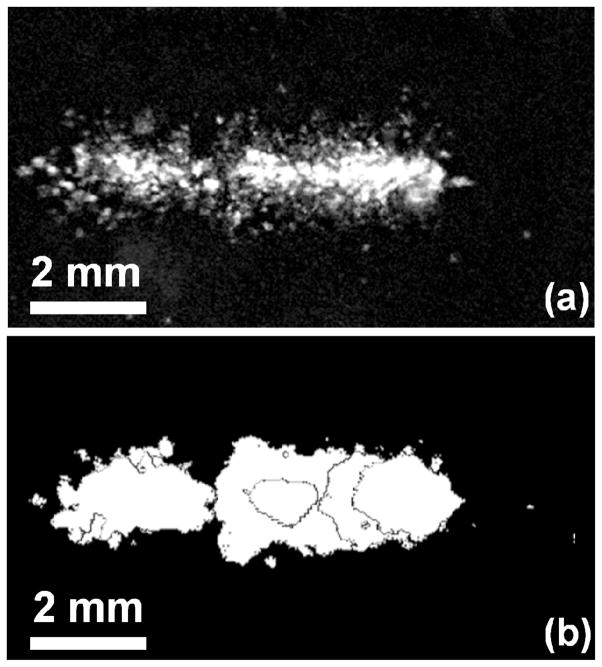

Lesions were not apparent immediately after cavitation collapse, but became visible within 1 second after ultrasound exposure. Undisrupted phantom appeared as a uniform translucent red plane within the phantom, while lesions in the gel showed increased light transmission and transparency, with a slight red or pink color. Therefore, lesions were identified and characterized based on the increased local light intensity observed while backlighting the phantom. From the profiles of the cavitation activity and resulting damage, it appears that the cloud at the center of the focal region is responsible for the large main lesion, while individual cavitation bubbles or small clusters in outlying regions of the phantom cause small areas of collateral damage (microlesions).

High-speed images were analyzed to compare the size and shape of lesions to that of the cavitation clouds. Overall, 15 clouds and corresponding lesions were compared for location, dimensions, and overlapping area between cavitation and lesions. The 3rd high-speed frame (corresponding to 20 μsec after the initial incidence of ultrasound) was used for comparison, as this showed the full bubble cloud as well as surrounding cavitation bubbles. It was found the location of lesions coincided well with the location of bubble clouds. Figure 8 shows a photograph captured by the high-speed camera of the bubble cloud in the phantom, as well as the subtraction image of the damage induced to the phantom during the single pulse. All lesions had similar morphology and dimensions to their corresponding bubble clouds. The overall area of the lesions (mean 1.7 mm2 ±1.2 mm2) was smaller than the area of the bubble clouds (mean 3.5 mm2 ± 1.9 mm2), although their locations coincided. Individual bubbles surrounding the main lesion had diameters of 171 ± 55 μm. The percentage of image area of the lesion overlapping the area of the bubble cloud was also computed, and it was found that between 94.6% – 100% of the damage for a given lesion occurred within the areas where bubbles were observed during the pulse (mean 98.4 %). These results suggest that the lesions appear in the phantom only where cavitation occurs. Without cavitation, lesions were not observed in the phantom. Some single bubbles also coincided with microlesions in the phantom in both size and shape. However, because the sensitive area of the phantom is two-dimensional, bubbles which were not in the plane of the RBC layer did not induce damage.

Figure 8.

Examples of a bubble cloud and the corresponding lesion generated after ultrasound exposure. Ultrasound (US) propagation is from left to right. (a) High speed image of the bubble cloud 5 μs after ultrasound pulse. (b) Subtraction image of the lesion generated by the single pulse. All lesions matched well in shape and dimensions with the corresponding bubble clouds. Lesions due to individual bubbles surrounding the focus are also evident.

DISCUSSION

Cavitation has been investigated extensively as a primary cause of ultrasound-induced tissue injury. However, it is difficult to observe the effects of cavitation in tissue in real time, and many mechanisms have been proposed for the cause of tissue-induced damage. Previous researchers have directly observed the interaction of cavitation with cells, either with liquid and gel cell suspensions (Brümmer et al. 1989; Hughes and Nyborg 1962; Miller et al. 1991, Williams et al. 1999), cell monolayers (Brayman et al. 1999), and vessel-mimicking phantoms (Zhong et al. 2001). We found that the tissue phantom described in this study can be used to directly observe cavitation and the resulting damage as it would occur in solid soft tissues, or at a soft tissue-liquid interface (such as the collecting ducts of kidneys or blood vessels)(Xu, et al. 2005). The phantom was found to be a very sensitive indicator of cavitation damage, with cell disruption visible even after a single, 10-cycle ultrasound pulse. Lesions generated by histotripsy in the tissue phantom matched those found in ex-vivo tissue in morphology, and were more visible than those in kidney tissue. Furthermore, the phantom provides a more controllable method to study the effects of different ultrasound parameters and transducers than ex-vivo tissue, which will inherently contain significant sample-to-sample variation.

The indicator of cavitation-induced lesions in the phantom is a change in transparency due to disruption of red blood cells, which are known to be susceptible to cavitation damage (Nyborg and Miller 1982). The primary contents of red blood cells are water and hemoglobin, in a ratio of approximately 2:1 by weight (Keitel et al. 1955). Using a long-distance microscope attached to the SIM 02 high-speed camera, we have also observed individual cells within the phantom during histotripsy exposure. When cavitation occurs in the phantom the cells are locally disrupted. However, the change in appearance at the cellular level only occurs some time after the cavitation. In Figure 9, the cells still appear intact directly after cavitation cloud collapse. Within 1 second after ultrasound incidence the lesion becomes fully developed. Although cavitation temporarily displaces cells with respect to their equilibrium position within the agarose, they return to this position after cavitation collapse. Afterwards, the field becomes uniform, indicating diffusion of red cell contents into the agarose. Based on these observations, it is hypothesized that no hemoglobin or other products of the red blood cells have been destroyed, but diffusion of cell contents into the agarose after membrane disruption creates a homogeneous agarose-hemoglobin mixture. Since the entire area of agarose-hemoglobin will be the same index of refraction, minimal scattering occurs compared with the areas containing intact red blood cells.

Figure 9.

High speed images of the cell phantom under 20× magnification. Prior to insonation, individual cells are observed in the agarose. After cavitation, the red blood cells are still visible as inhomogeneous regions (t = 300 μs). When another image is captured after 50 seconds, no cells are apparent in the area.

The disruption of cells by cavitation in the phantom caused lesions of similar morphology and lateral dimension as those formed in kidney. The axial length of several lesions in the kidneys extended to the distal surface of the kidney or into the medulla. In these instances, the lesions were only observed in the kidney cortex, limiting the length measured. However, the maximum length of lesions in phantom (19.8 mm) was similar to the maximum measured in kidney for lesions (19.4 mm). Therefore, the phantom appears to form lesions similar to ex-vivo soft tissue.

The boundaries of the lesion in the phantom were also very distinct, similar to tissue damage caused by histotripsy. The smaller areas of damage surrounding the central lesion, as seen in Figure 4, show no intermediate layer with reduced cell concentration, only total lack of cells or concentration similar to that of untreated phantom. This behavior suggests that damage to the phantom is a threshold phenomenon, and that red blood cells are either totally disrupted or remain completely intact. Moreover, a repeatable damage pattern was observed, with a large lesion at the center of the ultrasound focus and smaller lesions the size of individual cavitation bubbles. The phantoms containing axially-oriented lesions did not show circular spots of cavitation damage outside of the main lesion, but streaks through the RBC layer of the phantom parallel to the direction of propagation (Figure 3). This was not observed during single ultrasound pulses, suggesting the streaks are the cumulative effect of many pulses. The width of the streaks is similar to the diameter of the small lesions observed in the phantom. These show similar appearance to gel tunnels seen previously in agarose gels (Caskey et al. 2009; Williams and Miller 2003). Caskey et al. suggested that bubble jets played a role in tunnel formation and progression. The tunnels indicate that histotripsy damage may progress by translational movement of individual bubbles in the cloud, which each form a linear lesion. With a high enough density of bubbles, the tunnels will overlap and completely ablate the targeted zone over several hundred pulses.

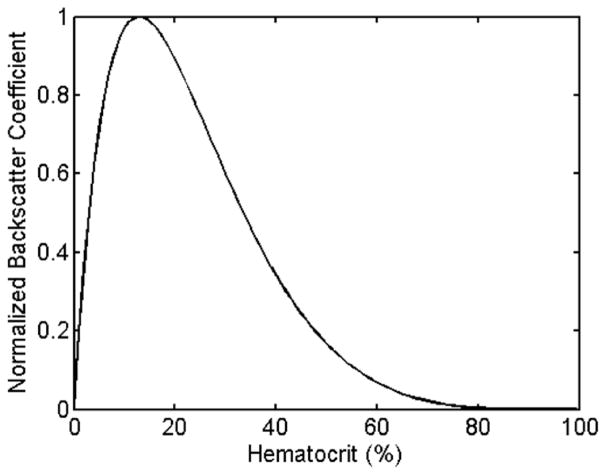

The response of the phantom to cavitation damage on a B-Mode image was indicated as a local hypoechoic zone. This feature of histotripsy is commonly observed in tissue, as is a useful feedback metric to indicate when significant disruption has occurred (Wang et al. 2009). Although flowing red blood cells typically have a hypoechoic appearance, static blood shows a speckle pattern, although at a reduced intensity from soft tissues (Hoskins 2007, Nicholas 1982, Raju and Srinivasan 2001, Turnbull et al. 1989). The backscatter from red blood cells has been studied previously and the backscatter coefficient (BSC) can be determined as a function of hematocrit and medium properties (Mo et al. 1994). Figure 10 shows our simulation of relative backscatter intensity vs. hematocrit of porcine red blood cells in agarose with an ultrasound frequency of 10 MHz using a Percus-Yevick packing theory for 3-D Rayleigh scattering as derived by Mo et al. At 5% hematocrit, the backscatter is a factor of 0.7 compared with the peak at 13%. However, high concentrations of RBCs will reduce light transmission, thus making high-speed imaging difficult. A hematocrit of 5% appears to be an acceptable compromise which allows both ultrasound and optical imaging simultaneously.

Figure 10.

Ultrasound backscatter coefficient (BSC) vs. blood hematocrit in agarose at 10 MHz. The peak occurs at 13% in this case. A 5% phantom yields has a BSC of 0.7 compared with the peak.

The demarcated lesions in the phantom were only found to occur at the location that cavitation clouds or individual cavitation bubbles were generated. Interestingly, the lesions formed were of similar extent and shape as the size of the bubble cloud shortly after the end of ultrasound exposure (within 10 μs), indicating that the bubble dimensions observed can provide an estimate of the damage. In this respect, if images of the bubble cloud are captured from each pulse over multiple pulses, the extent of damage may be estimated from an overlay of the images. We have demonstrated this by subjecting a phantom to 3 pulses of ultrasound, capturing and image of each bubble cloud and lesion formed. Figure 11 shows an overlay of the bubble clouds from all 3 pulses and the resulting lesion of damage produced from the 3 pulses. How lesions progress from pulse to pulse is a key aspect of histotripsy therapy, and will be studied in the future using the tissue phantom.

Figure 11.

Image of a lesion generated from 3 single ultrasound pulses (a) and overlapping images of 3 bubble clouds taken from binary images (b). Ultrasound propagation was from left to right. Lesion damage matches the shape and location of the bubble clouds, although appears darker near the edges of the cloud.

The cell phantom in this form has several limitations to be addressed. The most prominent is that it is 2-dimensional, and thus the entire lesion cannot be visualized optically, only a cross section. 3-dimensional phantoms of RBC-agarose can also be made, but the lesion formation cannot be observed in real time. Alternately, the full lesion volume can be estimated from the axial-lateral profile in the 2-dimensional phantom. However, alignment of the focus with the cell layer is critical to avoid obtaining an off-center cross-section and underestimating the focal dimensions. Multiple thin layers of red blood cells can be used to obtain the cross section at different planes in the phantom. The phantoms are also limited by temperature. The agarose mixture used in these experiments has a melting point of 70°C, limiting its potential use as a thermal indicator. For combined thermal/mechanical lesion visualization, another optically-transparent tissue-mimicking material with higher melting point must be used. The addition of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Lafon et al. 2005) can provide indication of thermal lesions in both the blood layer and transparent layers. Finally, the acoustic properties of the phantom were intermediate between water and soft tissue. The sound speed can be increased from ~1500 m/s to the expected soft tissue value of 1540 m/s by addition of a small quantity of glycerol (Inglis et al. 2006). Attenuation can also be increased with BSA. Finally, scatters such as graphite are often used to increase the backscatter to accurately mimic specific tissues.

While accuracy of the acoustic characteristics undoubtedly plays an important role in imaging, the most important effects will be from properties that affect cavitation behavior. Models of cavitation response to ultrasound in a viscoelastic medium (Yang and Church 2005) predict that the bubble response varies significantly with tissue elasticity. In the RBC phantom, the measured elasticity of the gel was 62 kPa, which matches well compared with literature values for 1.5% concentration agarose (Ramzi et al. 1998). This value is somewhat higher than most soft tissues, which are on the order of 10 kPa (Egorov et al. 2008). However, the elasticity of the gel can be predictably modified by agarose concentration to more accurately mimic specific tissue types (Normand et al. 2000).

SUMMARY

We have developed a tissue phantom which can be used to visualize mechanical damage caused by acoustic cavitation. The phantom has reasonable acoustic and mechanical properties compared with soft tissues. Histotripsy lesions generated in the phantom had similar morphology to those generated in kidney tissue. Furthermore, the local reduction of echogenicity on a B-Mode image of the phantom occurred where lesions were formed, a behavior consistent with that of tissue treated by histotripsy. The lesions only appeared where cavitation was observed by high-speed imaging, and were apparent even after a single ultrasound pulse. Given these results, the phantom appears to be a sensitive and accurate indicator of cavitation damage.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported under a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship. This work is funded by grants from the National Institute of Health (R01 EB008998, R01 HL077629, R01 CA134579 and S10RR022425), The Wallace H. Coulter Foundation, and The Hartwell Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arora D, Cooley D, Perry T, Skliar M, Roemer RB. Direct thermal dose control of constrained focused ultrasound treatments: phantom and in vivo evaluation. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2005;50:1919–35. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/8/019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayman AA, Lizotte LM, Miller MW. Erosion of artificial endothelia in vitro by pulsed ultrasound: acoustic pressure, frequency, membrane orientation and microbubble contrast agent dependence. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1999;25:1305–20. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brümmer F, Brenner J, Bräuner T, Hülser DF. Effect of shock waves on suspended and immobilized L1210 cells. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1989;15:229–39. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(89)90067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canney MS, Bailey MR, Crum LA, Khokhlova VA, Sapozhnikov OA. Acoustic characterization of high intensity focused ultrasound fields: A combined measurement and modeling approach. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2008;124:2406–20. doi: 10.1121/1.2967836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caskey CF, Qin S, Dayton PA, Ferrera KA. Microbubble tunneling in gel phantoms. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2009;125:EL183–EL89. doi: 10.1121/1.3097679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divkovic GW, Liebler M, Braun K, Dreyer T, Huber PE, Jenne JW. Thermal Properties and Changes of Acoustic Parameters in an Egg White Phantom During Heating and Coagulation by High Intensity Focused Ultrasound. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2007;33:981–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egorov V, Tsyuryupa S, Kanilo S, Kogit M, Sarvazyan A. Soft tissue elastometer. Medical Engineering & Physics. 2008;30:206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TL, Fowlkes B, Cain CA. A real-time measure of cavitation induced tissue disruption by ultrasound imaging backscatter reduction. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control. 2007;54:569–75. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2007.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TL, Hempel CR, Lake AM, Kieran K, Ives K, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA, Roberts WW. Histotripsy for the treatment of BPH: evaluation in a chronic canine model. IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. 2008:765–67. [Google Scholar]

- He P. Direct measurement of ultrasonic dispersion using a broadband transmission technique. Ultrasonics. 1999;37:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Holt RG, Roy RA. Measurements of bubble-enhanced heating from focused, mhz-frequency ultrasound in a tissue-mimicking material. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2001;27:1399–412. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00438-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins PR. Physical Properties of Tissues Relevant to Arterial Ultrasound Imaging and Blood Velocity Measurement. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2007;33:1527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DE, Nyborg WL. Cell Disruption by Ultrasound. Science. 1962;138:108–14. doi: 10.1126/science.138.3537.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis S, Ramnarine KV, Plevris JN, McDicken WN. An anthropomorphic tissue-mimicking phantom of the oesophagus for endoscopic ultrasound. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2006;32:249–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keitel HG, Berman H, Jones H, Maclachlan E. The Chemical Composition of Normal Human Red Blood Cells, including Variability among Centrifuged Cells. Blood. 1955;10:370–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieran K, Hall TL, Parsons JE, Wolf JS, Jr, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA, Roberts WW. Refining Histotripsy: Defining the Parameter Space for the Creation of Nonthermal Lesions With High Intensity, Pulsed Focused Ultrasound of the In Vitro Kidney. The Journal of Urology. 2007;178:672–76. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafon C, Khokhlova VA, Kaczkowski PJ, Bailey MR, Sapozhnikov OA, Crum LA. Use of a bovine eye lens for observation of HIFU-induced lesions in real-time. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2006;32:1731–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafon C, Zderic V, Noble ML, Yuen JC, Kaczkowski PJ, Sapozhnikov OA, Chavrier F, Crum LA, Vaezy S. Gel phantom for use in high-intensity focused ultrasound dosimetry. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2005;31:1383–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lierke EG, Hemsel T. Focusing cross-fire applicator for ultrasonic hyperthermia of tumors. Ultrasonics. 2006;44:e341–e44. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H-L, Chen W-S, Chen J-S, Shih T-C, Chen Y-Y, Lin W-L. Cavitation-enhanced ultrasound thermal therapy by combined low- and high-frequency ultrasound exposure. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2006;32:759–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhong P. High Intensity Focused Ultrasound Induced Transgene Activation in a Cell-Embedded Tissue Mimicking Phantom. IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. 2006:1746–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lokhandwalla M, Sturtevant B. Mechanical haemolysis in shock wave lithotripsy (SWL): I. Analysis of cell deformation due to SWL flow-fields. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2001;46:413–37. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/2/310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DL, Thomas RM, Williams AR. Mechanisms for hemolysis by ultrasonic cavitation in the rotating exposure system. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1991;17:171–78. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(91)90124-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo LY, Kuo IY, Shung KK, Ceresne L, Cobbold RS. Ultrasound scattering from blood with hematocrits up to 100% IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering. 1994;41:91–95. doi: 10.1109/10.277277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas D. Evaluation of backscattering coefficients for excised human tissues: results, interpretation and associated measurements. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1982;8:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Normand V, Lootens DL, Amici E, Plucknett KP, Aymard P. New Insight into Agarose Gel Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1:730–38. doi: 10.1021/bm005583j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyborg WL, Miller DL. Biophysical implications of bubble dynamics. Applied Scientific Research. 1982;38:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ophir J, Alam S, Garra B, Kallel F, Konofagou E, Krouskop T, Merritt C, Righetti R, Souchon R, Srinivasan S, Varghese T. Elastography: Imaging the elastic properties of soft tissues with ultrasound. Journal of Medical Ultrasonics. 2002;29:155–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02480847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju BI, Srinivasan MA. High-frequency ultrasonic attenuation and backscatter coefficients of in vivo normal human dermis and subcutaneous fat. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2001;27:1543–56. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00456-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramzi M, Rochas C, Guenet J-M. Structure-Properties Relation for Agarose Thermoreversible Gels in Binary Solvents. Macromolecules. 1998;31:6106–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sondén A, Svensson B, Roman N, Brismar B, Palmblad J, Kjellström BT. Mechanisms of shock wave induced endothelial cell injury. Lasers in Surgery and Medicine. 2002;31:233–41. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu J, Matula TJ, Bailey MR, Crum LA. Evaluation of a shock wave induced cavitation activity both in vitro and in vivo. Physics in Medicine and Biology. 2007;52:5933–44. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/52/19/014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull DH, Wilson SR, Hine AL, Foster FS. Ultrasonic characterization of selected renal tissues. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1989;15:241–53. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(89)90068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T-Y, Xu Z, Winterroth F, Hall TL, Fowlkes JB, Rothman ED, Roberts WW, Cain CA. Quantitative ultrasound backscatter for pulsed cavitational ultrasound therapy-histotripsy. Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics and Frequency Control, IEEE Transactions on. 2009;56:995–1005. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2009.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Miller DL. Photometric detection of ATP release from human erythrocytes exposed to ultrasonically activated gas-filled pores. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1980;6:251–56. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(80)90020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AR, Miller DL. The use of transparent aqueous gels for observing and recording cavitation activity produced by high intensity focused ultrasound. IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. 2003;2:1455–58. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JC, Woodward JF, Stonehill MA, Evan AP, McAteer JA. Cell damage by lithotripter shock waves at high pressure to preclude cavitation. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 1999;25:1445–49. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Kaufman JJ. Diffraction correction methods for insertion ultrasound attenuation estimation. Biomedical Engineering, IEEE Transactions on. 1993;40:563–70. doi: 10.1109/10.237676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Fan Z, Hall TL, Winterroth F, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA. Size Measurement of Tissue Debris Particles Generated from Pulsed Ultrasound Cavitational Therapy - Histotripsy. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2009;35:245–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Fowlkes JB, Ludomirsky A, Cain CA. Investigation of intensity thresholds for ultrasound tissue erosion. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2005;31:1673–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Fowlkes JB, Rothman ED, Levin AM, Cain CA. Controlled ultrasound tissue erosion: The role of dynamic interaction between insonation and microbubble activity. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;117:424–35. doi: 10.1121/1.1828551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Church CC. A model for the dynamics of gas bubbles in soft tissue. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;118:3595–606. doi: 10.1121/1.2118307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong P, Zhou Y, Zhu S. Dynamics of bubble oscillation in constrained media and mechanisms of vessel rupture in SWL. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2001;27:119–34. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(00)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]