Abstract

Background

Updated, robust estimates of the incidence and prevalence of rare long-term neurological conditions in the UK are not available. Global estimates may be misrepresentative as disease aetiology may vary by location.

Objectives

To systematically review the incidence and prevalence of long-term neurological conditions in the UK since 1988.

Search Strategy

Medline (January 1988 to January 2009), Embase (January 1988 to January 2009), CINAHL (January 1988 to January 2009) and Cochrane CENTRAL databases.

Selection Criteria

UK population-based incidence/prevalence studies of long-term neurological conditions since 1988. Exclusion criteria included inappropriate diagnoses and incomprehensive case ascertainment.

Data Collection and Analysis

Articles were included based on the selection criteria. Data were extracted from articles with ranges of incidence and prevalence reported. Main Results: Eight studies met the criteria (3 on motor neurone disease; 4 on Huntington's disease; 1 on progressive supranuclear palsy). The incidence of motor neurone disease ranged from 1.06 to 2.4/100,000 person-years. The prevalence ranged from 4.02 to 4.91/100,000. The prevalence of Huntington's disease ranged from 4.0 to 9.94/100,000. The prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy ranged from 3.1 to 6.5/100,000.

Conclusions

The review updates the incidence/prevalence of long-term neurological conditions. Future epidemiological studies must incorporate comprehensive case ascertainment methods and strict diagnostic criteria.

Key Words: Motor neurone disease, Huntington's disease, Multiple system atrophy, Progressive supranuclear palsy, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Postpolio syndrome, Dominantly inherited ataxias

Introduction

Progressive neurological diseases vary in presentation, both in timescale and severity. This review forms part of a Policy Research Programme commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research to assess disease burden on service user, family and health and social care services. The investigated conditions were requested by the commission to encompass a range of aetiologies, symptoms, diagnoses and prognoses.

Rationale and Aim of Review

The aim was to systematically identify and update the incidence and prevalence of the following long-term neurological conditions:

-

•

Motor neurone disease

-

•

Huntington's disease

-

•

Progressive supranuclear palsy

-

•

Multiple system atrophy

-

•

Postpolio syndrome

-

•

Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

-

•

Dominantly inherited ataxias

Knowledge of these data is valuable in informing future research and health service policies.

Methods

The review protocol is accessible at http://www.ltnc.org.uk/research_files/RESULT_study.html. Population-based studies of incidence and prevalence were sought.

Scoping Search

A scoping search identified existing reviews of incidence and prevalence. Existing reviews would be updated, not repeated. Medline (Ovid; 1950 to week 2 of 2009], Embase (Ovid; 1980 to week 46 of 2008], CINAHL (Ovid; 1982 to week 1 of 2009], the Science Citation Index, Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) and Centre for Reviews and Dissemination databases were searched.

Main Search Strategy

The search strategy (Appendix 1) identified articles from Medline, Embase and CINAHL. The Cochrane Library (CENTRAL) and databases of ongoing research and unpublished literature were also searched. Reference lists of included articles were assessed to capture further articles omitted from the search strategy.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Articles were included based on the criteria outlined in table 1. Comprehensive case ascertainment was required in order to ensure maximum patient capture. Studies before 1988 were excluded as the review aimed to present up-to-date statistics. Strict diagnostic criteria were set to minimise bias from misdiagnoses. Inclusion was based on agreement between 2 of the independent reviewers (T.H., J.C., G.J., J.R.). In cases of non-consensus, a third independent review was obtained. In cases of incomprehensive study methodology, authors were approached to determine a study's potential inclusion.

Table 1.

Selection criteria

|

Diagnostic criteria available in Appendix 2.

Data Extraction

The following data were extracted into tables:

-

•

Source: authors and journal published

-

•

Study design: e.g. cross-sectional, cohort, etc.

-

•

Population denominator

-

•

Timescale: incidence time frame and prevalence date

-

•

Case ascertainment method

-

•

Diagnostic method

-

•

Outcome: incidence per 100,000 person-years; prevalence per 100,000 of population

-

•

Methodological limitations

-

•

Potential bias

Data Analyses

Incidences were reported as ranges. Pooling statistics was not possible due to methodological heterogeneity and shared population denominations between certain studies.

Results

Existing Systematic Reviews

No existing systematic reviews of incidence and prevalence were identified.

Study Yield

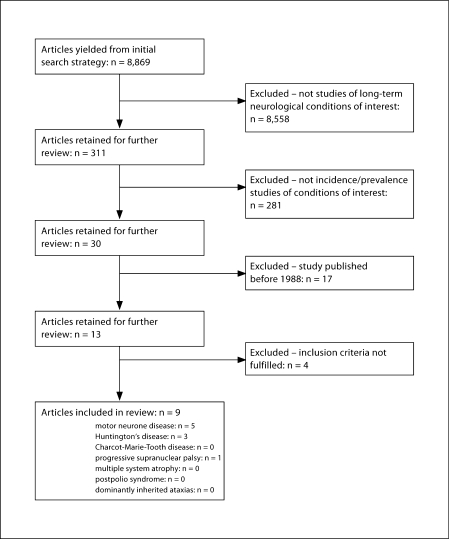

The initial search yielded 8,869 references; 311 were identified as potentially relevant. Of these, 9 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of included/excluded articles.

Included Studies by Condition

Motor Neurone Disease (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis)

Five studies assessed the incidence/prevalence of motor neurone disease (table 2). Total population coverage was 11,498,075, although some overlap between studies emerged. The incidence of motor neurone disease in the UK ranged from 1.06 to 2.4/100,000 person-years (including all diagnostic categories of the World Federation of Neurology, WFN, and El Escorial criteria). The prevalence ranged from 4.02 to 4.91/100,000 of the populations studied.

Table 2.

Details of included studies

| Source/condition | Design | Population/denominator | Timescale | Case ascertainment method | Diagnostic method | Outcome | Potential bias/methodological limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abhinav etal. (2007) [1] ALS | Population-based study of incidence and prevalence | South East London boroughs (Lambeth, South-wark, Lewisham, Bexley, Greenwich, Bromley), Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, and Kent; population of 2,890,482 based on 2001 census (excluding population under 15 years of age) | Incidence between January 1, 2002, and June 30, 2006; prevalence on June 30,2006 | SEALS registry used to identify cases since 1997; department general hospitals, neurology units checked; list of patients referred to healthcare professionals with suspected ALS assessed to ensure maximum ascertainment | El Escorial criteria cases (suspected, possible, probable and definite); diagnosed by 2 consultant neurologists, and review of case notes to confirm diagnoses | 138 incident cases during time period; 142 alive on point prevalence date; incidence of 1.06/100,000 person-years; prevalence of 4.91/100,000 | Possibility of low levels of missed case ascertainment in elderly category where patients seen by geriatricians not covered by capture sources; however, ascertainment likely to be high due to multiple overlapping sources |

| Forbes etal. (2007) [2] ALS | Population-based study of incidence | Scotland; population estimated at 5,125,000 in mid-1994 | Incidence from January 1,1989, to December 31, 1999 | Cases identified from national register of MND since 1989; neuroreferrals, nurse specialist records, Scottish morbidity records and mortality coding checked to ensure maximum case ascertainment | WFN criteria before 1994; El Escorial criteria after 1994; not specified which El Escorial categories included | 1,226 incident cases; incidence of 2.4/100,000 person-years | Estimated that 2.2% of patients went unobserved from the 2-source capture-recapture method; therefore, reported statistics possibly underestimated; inclusion of this estimate would increase incidence to 2.44/100,000 person-years |

| Johnston etal. (2006) [3] ALS | Population-based study of incidence and prevalence | London boroughs of Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham; population of approx. 615,040 based on Office for National Statistics | Incidence from January 1,1997, to July 31, 2004; prevalence on July 31, 2004 | Cases ascertained from the ALS ward and clinic, neurophysiology department and physiotherapy department at King's College Hospital; records from National Hospital, Queen Square, also assessed | El Escorial criteria (suspected, possible, probable and definite cases); also assessed El Escorial definite and probable cases only, and the revised WFN criteria | El Escorial criteria:

|

Below-average proportion of elderly individuals in the population (5 vs. 7.6% national average) likely to result in lower incidence in population; however, this is a population trait rather than a methodological limitation |

| Mitchell etal. (1998) [4] ALS | Population-based study of incidence | Lancashire and South Cumbria; population of 1,473,153 based on 1991 census | Incidence from January 1,1989, to December 31, 1993 | Cases ascertained from clinical records at the Preston Department of Neurology and Neuro-physiology, and district general hospitals – these units cover the entire study catchment area; small numbers of patients living in study catchment ascertained from departments serving neighbouring catchments | Detailed clinical assessment, full inpatient investigation including: EMG, nerve conduction, muscle biopsy, CT, myelography, CSF, immunoelectrophoresis, glucose tolerance and thyroid function; assessments made by at least 2 consultant neurologists before definitive diagnosis | Incidence of 1.76/100,000 person-years | Study did not use standardised diagnostic criteria as before El Escorial; however, extensive methods used in diagnosis; case ascertainment likely to be close to fully complete as study centres are English steering centres for European MND registry, which requires a 'true' population-based knowledge of all MND patients living in the catchment |

| James etal. (1994) [5] ALS | Population-based study of prevalence | South and Mid Glamorgan, and Gwent; population of 1,394,400 based on 1991 census | Prevalence estimated on June 22,1992 | Inpatient register at the department of neurology and GP registers within the catchment area | WFN criteria (suspected, possible, probable and definite cases); WFN criteria definite and probable cases only also assessed | Prevalence of 4.02/100,000 for all cases; prevalence of 2.73/100,000 for definite and probable cases at diagnosis | None identified |

ALS = Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; SEALS = South-East England Register for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis; MND = motor neurone disease; GP = general practitioner; EMG = electromyography; CSF = cerebrospinal fluid.

Huntington's Disease

Three studies assessed the prevalence of Huntington's disease (table 3). No reports of incidence were identified. Total population coverage was 5,483,871. The prevalence ranged from 4.0 to 6.4/100,000 of the populations studied.

Table 3.

Details of included studies

| Source/ condition | Design | Population/ denominator | Timescale | Case ascertainment method | Diagnostic method | Outcome | Potential bias/methodological limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morrison et al. (1995) [6] HD | Population-based study of prevalence | Northern Ireland population of 1,569,971 based on 1991 national census | Prevalence estimated on April 21, 1991 | Northern Ireland GP records; neurologist, psychiatrist and geriatrician records; Department of Medical Genetics diagnostic records | DNA-confirmed diagnoses for all patients | Prevalence of 6.4/100,000 | Small founder effect due to large families; however, families not large enough to cause bias in population statistics |

| James et al. (1994) [7] HD | Population-based study of prevalence | South and Mid Glamorgan, and Gwent; population of 1,393,900 based on 1991 national census | Prevalence estimated on March 1, 1994 | HD register for South Wales | Details of formal diagnosis in register; notes of symptom type and onset provided | Prevalence of 6.2/100,000 | All known living cases of HD studied; potential for cases not included in register, and subsequent underestimation of prevalence |

| Watt and Seller (1993) [8] HD | Population-based study of prevalence | Oxford Region Health Authority under NHS; population of 2,520,000 | Prevalence estimated on live patients on January 1, 1988 | Oxford region medical genetics department records; it is thought by the time of the study all persons affected in 1988 would have been referred and ascertained | Confirmed by presymptomatic linkage test | Prevalence of 4.0/100,000 | None identified |

HD = Huntington's disease; NHS = National Health Service; GP = general practitioner.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

One study assessed the prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy (table 4). The study included 3 substudies. A national study of the entire UK population, a regional study covering a catchment of 2,598,240 and a community study covering a catchment of 259,998 people. The prevalence ranged from 1.0/100,000 in the national study to 6.5/100,000 in the community study. However, only the community study had a comprehensive case ascertainment and we therefore report these statistics in our results.

Table 4.

Details of included studies

| Source/condition | Design | Population/denominator | Timescale | Case ascertainment method | Diagnostic method | Outcome | Potential bias/methodological limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nath et al. (2001) [9] PSP | Population-based study of prevalence | 3 substudies;

|

Prevalence on January 1, 1999 |

|

Possible or probable cases based on NINDS- SPSP criteria |

|

Smaller population denominator at each level of study led to more extensive capture methods, hence the greater prevalence in smaller denomination studies; national study did not use active case ascertainment methods and thought up to 81% of cases unidentified |

PSP = Progressive supranuclear palsy; GP = general practitioner; NINDS-SPSP = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Society for Progressive Supranuclear Palsy.

Results Summary

Table 5 illustrates a summary of results identified in the study.

Table 5.

Ranges of prevalence/incidence of the long-term conditions

| Incidence range, cases per 100,000 person-years | Prevalence range, cases per 100,000 of population | |

|---|---|---|

| Motor neurone disease | 1.06-2.4 | 4.02–4.91 |

| Huntington's disease | not reported | 4.0–6.4 |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy | not reported | 6.5 |

| Multiple system atrophy | not reported | not reported |

| Dominantly inherited ataxias | not reported | not reported |

| Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease | not reported | not reported |

| Postpolio syndrome | not reported | not reported |

Excluded Studies

Four studies illustrated in table 6 were excluded from the review.

Table 6.

Excluded studies

| Disease | Reason for exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Craig et al. (2005) [10] | Dominantly inherited ataxias | Incomprehensive case ascertainment: investigation of a cohort of families with undiagnosed ataxias and suspected Huntington's disease; there may be additional cases outside the cohort studied, hence incomplete case ascertainment |

| Craig et al. (2004) [11] | Dominantly inherited ataxias | Incomprehensive case ascertainment: investigation of already clinically affected families; no broader searches, therefore possibility of further cases in families not studied, hence incomplete case ascertainment possible |

| Schrag et al. (1999) [12] | Multiple system atrophy/progressive supranuclear palsy | Incomprehensive case ascertainment: 33/202 patients (16%) identified as potential progressive supranuclear palsy/multiple system atrophy patients declined to be assessed further, therefore complete case ascertainment was not possible; estimates of incidence/prevalence are likely to be too low |

| Simpson and Johnston (1989) [13] | Huntington's disease | Although study published after 1988, data refer to pre-1988 incidence and prevalence |

Unreported Conditions

No articles relating to postpolio syndrome, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, multiple system atrophy and dominantly inherited ataxias in the UK were identified that met the inclusion criteria. However, some studies were identified that did not meet the required criteria. Whilst it would be inappropriate to include these studies in the results, table 7 provides incidence and prevalence statistics for excluded studies in conditions not represented in the results to provide at least some information on these conditions. However, one must view these results with caution due to the associated methodological limitations.

Table 7.

Details of excluded studies of conditions not represented in the review

| Source/ condition | Design | Population/ denominator | Timescale | Case ascertainment method | Diagnostic method | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schrag et al. (1999) [12] MSA/PSP | Population-based study of incidence and prevalence | 15 general practices from a linkage scheme in the London region; population of 121,608 | Prevalence on July 1, 1997 | Computerised records screened, with deliberate overascertainment to include all possible cases; neurologist reviewed eligible records and excluded where appropriate; 241 eligible patients, 202 agreed to be assessed for diagnosis | Computerised records reviewed; neurological interview and assessment including questionnaires and video to capture neurological symptoms; longitudinal assessments to identify developing symptoms of conditions |

|

| Craig et al. (2004) [11] SCA6 | Population-based study of prevalence | North-east government region; population of 2,516,500 | Prevalence on June 30, 2001 | SCA6 families identified and studied | Molecular genetic and haplotype analyses | 32 affected individuals from 16 genealogically distinct families; DNA only available for 26; minimum prevalence of 1.59/100,000 (95% CI: 1.04–2.14) in population aged over 16 years, and of 3.18/100,000 (95% CI: 2.08–4.28) in those >45 years old |

| Craig et al. (2005) [10] SCA17 | Population-based study of prevalence | North-east government region; population of 2,516,500 | Prevalence on June 30, 2001 | 192 families with undiagnosed ataxia and 90 families with suspected Huntington's disease studied | Molecular genetic and haplotype analyses | 2 patients identified with CAG expansion greater than control; each had an affected sister; minimum prevalence of 0.16/100,000 (95% CI, upper value: 0.31) |

MSA = Multiple system atrophy; PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy; SCA = spinocerebellar ataxia.

Discussion

The review aimed to systematically report the incidence and prevalence of long-term neurological conditions in the UK. Review findings and the variation between studies are discussed.

Motor Neurone Disease

Some variation in incidence is evident. An incidence of 1.06/100,000 person-years was found in South East England [1], compared to 2.4 in Scotland [2]. Differences in age structure between geographical locations may influence variations in incidence and prevalence rates. The literature suggests that onset generally occurs after 40 years age, with a peak incidence between 55 and 75 years [14,15]. Data from the 2001 census [16,17] indicate that 32% of the population of Greater London are over 45 years of age compared to 40% of the Scottish population. Furthermore, approximately 10% of the Greater London population are in the 60- to 75-year age bracket compared to 14% in Scotland. Such statistics are likely to make small differences in incidence and prevalence rates but would not account for any large differences. Other than these geographical considerations, there is no evidence of environmental factors to explain differences. Familial cases are reported as less than 10%, making it unlikely that geographical clustering of families with motor neurone disease affected observed figures. Methodological differences within the study design may explain observed differences. Omissions of small numbers of unidentified cases could influence rates reported substantially. However, case ascertainment and diagnostic methods appear similar, and differences could be attributable to chance.

The prevalence was consistent across studies, ranging from 4.02 to 4.91/100,000. These figures sit at the lower end of the reported global prevalence (4–10/100,000) [18,19,20,21,22]. However, it is worth noting that the actual prevalence may be higher as those without a diagnosis are not included in these estimates.

Huntington's Disease

The prevalence ranged from 4.0 to 6.4/100,000. This is contrary to reported global rates (0.4–0.5/100,000), but comparable to the prevalence reported in other Western countries (8–10/100,000) [23].

Differences in prevalence between studies could be attributable to geographical variation due to the hereditary nature of the disease. A previous study reported a prevalence of 9.94/100,000 in the Grampian region of Scotland in 1987 [13], compared to 4.0/100,000 in Oxfordshire in 1993 [8]. Authors report the Grampian region to have low migration levels due to thriving local communities, compared to relatively high migration in the Oxfordshire region. A closed gene pool population compared to a population with high migration rates may explain such discrepancies.

The possibility of methodological differences between studies remains and could be a factor in reported discrepancies. Case ascertainment appears consistent between the studies. However, some studies used a genetic test as a diagnostic confirmation [6], whereas others appeared to assess records and registers for diagnostic confirmation [7]. Consequently, in studies using genetic testing, positive diagnoses were made for presymptomatic patients, which was not possible in studies where only symptomatic patients were included. As mentioned previously, in rare conditions incomplete case ascertainment or disease misclassification can skew the reported incidence/prevalence significantly in both directions.

Progressive Supranuclear Palsy

Evidence suggests progressive supranuclear palsy is sporadic. Tau gene mutations have been identified as a predisposition. However, two thirds of the global population possess this polymorphism. Consequently, other factors may be more important in progressive supranuclear palsy.

The prevalence ranged from 1.0/100,000 in the national study by Nath et al. [9] to 6.5/100,000 in the community study by the same authors. However, the authors admit the case ascertainment was not ‘active’ and fully comprehensive due to the denominator size and report that 81% of the cases may be unascertained based on the community study prevalence. The regional study fits within the reported global prevalence range (1.39–5.8/100,000) [24,25,26]. As the condition is sporadic, the greater prevalence observed in the community study is probably due to a more complete case ascertainment.

General Points

A fundamental point is that the incidence and prevalence reported should be regarded as minimum figures. Assuming studies had 100% case ascertainment of diagnosed patients, the statistics would still omit undiagnosed patients. Consequently, such studies will underpredict incidence and prevalence. One could argue that due to the lack of firm diagnostic criteria, diagnoses may switch between conditions, resulting in under- and overestimation of figures. However, misclassifications and changes in diagnoses would have insignificant bearing on statistics in comparison to the magnitude of effect of an exclusion of undiagnosed patients.

Non-Reported Conditions

No studies of the incidence/prevalence of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease or postpolio syndrome were identified. In Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, this was surprising as it is reported as the most prevalent condition in global studies [27]. Furthermore, one may expect more extensive research with follow-up in a non-life-limiting condition. With regard to postpolio syndrome, despite a number of intervention trials [28,29,30,31,32,33], the lack of reported incidence/prevalence may reflect difficulties in confirming diagnoses due to the symptoms being similar to those associated with natural ageing. Accurate case ascertainment would be difficult and expose statistics to bias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the review reported incidence/prevalence ranges for the long-term neurological conditions from all identified studies in the UK since 1988. The rates varied between studies, particularly for Huntington's disease, possibly attributable to geographical variation. The exclusion of articles due to methodological limitations suggests future epidemiological studies require comprehensive case ascertainment and strict and standardised diagnostic methods. Such safeguards will ensure more comprehensive reviews of incidence and prevalence, covering a wider denominator population of the UK.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank University of Birmingham librarian Nancy Graham for her expertise and assistance with developing the search strategy for the review. The review was conducted as part of a Policy Research Programme funded by the National Institute for Health Research.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

| Medline (Ovid) 1950 – week 2, 2009 | |

| 1 | exp Huntington's Disease |

| 2 | exp Motor Neurone Disease |

| 3 | exp Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| 4 | exp Multiple System Atrophy |

| 5 | exp Postpoliomyelitis Syndrome |

| 6 | exp Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease |

| 7 | exp Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies |

| 8 | exp Supranuclear Palsy, Progressive |

| 9 | spinocerebellar ataxia |

| 10 | episodic ataxia |

| 11 | dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy |

| 12 | DPRLA |

| 13 | long-term neurological conditions.mp. |

| 14 | progressive neurological conditions.mp. |

| 15 | progressive neurological disease.mp. |

| 16 | exp Epidemiology |

| 17 | exp Incidence |

| 18 | exp Prevalence |

| 19 | exp Diagnosis |

| 20 | exp Prognosis |

| 21 | or/1–15 |

| 22 | or/16–20 |

| 23 | 21 and 22 |

| 24 | limit 23 to (English language and yr = “1988–2009”) |

| Embase (Ovid) 1980 – week 46, 2008 | |

| 1 | exp Huntington's Disease |

| 2 | exp Motor Neurone Disease |

| 3 | exp Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| 4 | exp Multiple System Atrophy |

| 5 | exp Postpoliomyelitis Syndrome |

| 6 | exp Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease |

| 7 | exp “Hereditary Motor and Sensory Neuropathies” |

| 8 | exp Supranuclear Palsy, Progressive |

| 9 | spinocerebellar ataxia |

| 10 | episodic ataxia |

| 11 | dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy |

| 12 | DPRLA |

| 13 | long-term neurological conditions.mp. |

| 14 | progressive neurological conditions.mp. |

| 15 | progressive neurological disease.mp. |

| 16 | exp Epidemiology |

| 17 | exp Incidence |

| 18 | exp Prevalence |

| 19 | exp Diagnosis |

| 20 | exp Prognosis |

| 21 | or/1–15 |

| 22 | or/16–20 |

| 23 | 21 and 22 |

| 24 | limit 23 to (English language and yr = “1988–2009”) |

| CINAHL (Ovid) 1982 – week 1, 2009 | |

| 1 | MH “Huntington's Disease” |

| 2 | MH “Motor Neurone Diseases+” |

| 3 | MH “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis” |

| 5 | MH “Postpoliomyelitis Syndrome” |

| 6 | MH “Neropathies, Hereditary Motor and Sensory” |

| 8 | MH “Supranuclear Palsy, Progressive” |

| 9 | “spinocerebellar ataxia” |

| 10 | “episodic ataxia” |

| 11 | “dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy” |

| 12 | “DPRLA” |

| 12 | “long-term neurological conditions” |

| 13 | “progressive neurological conditions” |

| 14 | “progressive neurological disease” |

| 15 | MH “Epidemiology+” |

| 16 | MH “Incidence” |

| 17 | MH “Prevalence” |

| 18 | MH “Diagnosis+” |

| 19 | MH “Prognosis+” |

| 20 | or/1–14 |

| 21 | or/15–19 |

| 22 | 20 and 21 |

| 23 | limit 22 to (English language and years = “Jan 1988–Jan 2009”) |

Appendix 2

Appendix 2

| Diagnostic criteria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- 1.Abhinav K, Stanton B, Johnston C, Hardstaff J, Orrell RW, Howard R, Clarke J, Sakel M, Ampong M-A, Shaw CE, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in South-East England: a population-based study. The South-East England Register for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (SEALS Registry) Neuroepidemiology. 2007;29:44–48. doi: 10.1159/000108917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes RB, Colville S, Parratt J, Swingler RJ. The incidence of motor neuron disease in Scotland. J Neurol. 2007;254:866–869. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0454-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson C, Stanton BR, Turner MR, Gray R, Blunt AH, Butt D, Ampong MA, Shaw CE, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in an urban setting: a population-based study of inner city London. J Neurol. 2006;253:1642–1643. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell JD, Gatrell AC, Al-Hamad A, Davies RB, Batterby G. Geographical epidemiology of residence of patients with motor neuron disease in Lancashire and south Cumbria. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:842–847. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.6.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James CM, Harper PS, Wiles CM. Motor neurone disease: a study of prevalence and disability. QJM. 1994;87:693–699. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morrison PJ, Johnston WP, Nevin NC. The epidemiology of Huntington's disease in Northern Ireland. J Med Genet. 1995;32:524–530. doi: 10.1136/jmg.32.7.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James CM, Houlihan GD, Snell RG, Cheadle JP, Harper PS. Late-onset Huntington's disease: a clinical and molecular study. Age Ageing. 1994;23:445–448. doi: 10.1093/ageing/23.6.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watt DC, Seller A. A clinico-genetic study of psychiatric disorder in Huntington's chorea. Psychol Med. 1993;(suppl 23):1–46. doi: 10.1017/s0264180100001193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nath U, Ben-Shlomo Y, Thomson RG, Morris HR, Wood NW, Lees AJ, Burn DJ. The prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy (Steele-Richardson-Olszewski syndrome) in the UK. Brain. 2001;124(pt 7):1438–1449. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.7.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craig K, Keers SM, Walls TJ, Curtis A, Chinnery PF. Minimum prevalence of spinocerebellar ataxia 17 in the north east of England. J Neurol Sci. 2005;239:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig K, Keers SM, Archibald K, Curtis A, Chinnery PF. Molecular epidemiology of spinocerebellar ataxia type 6. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:752–755. doi: 10.1002/ana.20110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schrag A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Quinn NP. Prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 1999;354:1771–1775. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson SA, Johnston AW. The prevalence and patterns of care of Huntington's chorea in Grampian. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:799–804. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.6.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Chalabi A, Andersen PM, Nilsson P, Chioza B, Andersson JL, Russ C, Shaw CE, Powell JF, Leigh PN. Deletions of the heavy neurofilament subunit tail in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:157–164. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atsuta N, Watanabe H, Ito M, Tanaka F, Tamakoshi A, Nakano I, Aoki M, Tsuji S, Yuasa T, Takano H, Hayashi H, Kuzuhara S, Sobue G, Research Committee on the Neurodegenerative Diseases of Japan Age at onset influences on wide-ranged clinical features of sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;276:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.2001 census. Office for National Statistics.

- 17.2001 census for Scotland. General Register Office for Scotland.

- 18.Norris FH, Jr, Calanchini PR, Fallat RJ, Panchari S, Jewett B. The administration of guanidine in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1974;24:721–728. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gubbay SS, Kahana E, Zilber N, Cooper G, Pintov S, Leibowitz Y. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a study of its presentation and prognosis. J Neurol. 1985;232:295–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00313868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ringel SP, Murphy JR, Alderson MK, Bryan W, England JD, Miller RG, Petajan JH, Smith SA, Roelofs RI, Ziter F, et al. The natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 1993;43:1316–1322. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.7.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pradas J, Finison L, Andres PL, Thornell B, Hollander D, Munsat TL. The natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and the use of natural history controls in therapeutic trials. Neurology. 1993;43:751–755. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haverkamp LJ, Appel V, Appel SH. Natural history of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in a database population: validation of a scoring system and a model for survival prediction. Brain. 1995;118:707–719. doi: 10.1093/brain/118.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mestre T, Ferreira J, Coelho MM, Rosa M, Sampaio C. Therapeutic interventions for symptomatic treatment in Huntington's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD006456. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006456.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Golbe LI, Davis PH, Schoenberg BS, Duvoisin RC. Prevalence and natural history of progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 1988;38:1031–1034. doi: 10.1212/wnl.38.7.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chio A, Magnani C, Schiffer D. Prevalence of Parkinson's disease in Northwestern Italy: comparison of tracer methodology and clinical ascertainment of cases. Mov Disord. 1998;13:400–405. doi: 10.1002/mds.870130305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wermuth L, Joensen P, Bünger N, Jeune B. High prevalence of Parkinson's disease in the Faroe Islands. Neurology. 1997;49:426–432. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skre H. Genetic and clinical aspects of Charcot-Marie-Tooth's disease. Clin Genet. 1974;6:98–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1974.tb00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vasconcelos OM, Prokhorenko OA, Salajegheh MK, Kelley KF, Livornese K, Olsen CH, Vo AH, Dalakas MC, Halstead LS, Jabbari B, Campbell WW. Modafinil for treatment of fatigue in post-polio syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2007;68:1680–1686. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261912.53959.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan KM, Amirjani N, Sumrain M, Clarke A, Strohschein FJ. Randomized controlled trial of strength training in post-polio patients. Muscle Nerve. 2003;27:332–338. doi: 10.1002/mus.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.On AY, Oncu J, Uludag B, Ertekin C. Effects of lamotrigine on the symptoms and life qualities of patients with post-polio syndrome: a randomized, controlled study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2005;20:245–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez H, Sunnerhagen KS, Sjöberg I, Kaponides G, Olsson T, Borg K. Intravenous immunoglobulin for post-polio syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:493–500. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farbu E, Rekand T, Vik-Mo E, Lygren H, Gilhus NE, Aarli JA. Post-polio syndrome patients treated with intravenous immunoglobulin: a double-blinded randomized controlled pilot study. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:60–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skough K, Krossén C, Heiwe S, Theorell H, Borg K. Effects of resistance training in combination with coenzyme Q10 supplementation in patients with post-polio: a pilot study. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:773–775. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks BR. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Diseases/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial ‘Clinical Limits of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis' Workshop Contributors. J Neurol Sci. 1994;124(suppl):96–107. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]