Abstract

We recently demonstrated that 11C-MePPEP, a PET ligand for CB1 receptors, has such high uptake in the human brain that it can be imaged for 210 min and that receptor density can be quantified as distribution volume (VT) using the gold standard of compartmental modeling. However, 11C-MePPEP had relatively poor retest and intersubject variabilities, which were likely caused by errors in the measurements of radioligand in plasma at low concentrations by 120 min. We sought to find an analog of 11C-MePPEP that would provide more accurate plasma measurements. We evaluated several promising analogs in the monkey brain and chose the 18F-di-deutero fluoromethoxy analog (18F-FMPEP-d2) to evaluate further in the human brain.

Methods

11C-FMePPEP, 18F-FEPEP, 18F-FMPEP, and 18F-FMPEP-d2 were studied in 5 monkeys with 10 PET scans. We calculated VT using compartmental modeling with serial measurements of unchanged parent radioligand in arterial plasma and radioactivity in the brain. Nonspecific binding was determined by administering a receptor-saturating dose of rimonabant, an inverse agonist at the CB1 receptor. Nine healthy human subjects participated in 17 PET scans using 18F-FMPEP-d2, with 8 subjects having 2 PET scans to assess retest variability. To identify sources of error, we compared inter-subject and retest variability of brain uptake, arterial plasma measurements, and VT.

Results

18F-FMPEP-d2 had high uptake in the monkey brain, with greater than 80% specific binding, and yielded less radioactivity uptake in bone than did 18F-FMPEP. High brain uptake with 18F-FMPEP-d2 was also observed in humans, in whom VT was well identified within approximately 60 min. Retest variability of plasma measurements was good (16%); consequently, VT had a good retest variability (14%), intersubject variability (26%), and intraclass correlation coefficient (0.89). VT increased after 120 min, suggesting an accumulation of radiometabolites in the brain. Radioactivity accumulated in the skull throughout the entire scan but was thought to be an insignificant source of data contamination.

Conclusion

Studies in monkeys facilitated our development and selection of 18F-FMPEP-d2,compared with 18F-FMPEP, as a radioligand demonstrating high brain uptake, high percentage of specific binding, and reduced uptake in bone. Retest analysis in human subjects showed that 18FFMPEP-d2 has greater precision and accuracy than 11C-MePPEP, allowing smaller sample sizes to detect a significant difference between groups.

Keywords: positron emission tomography, brain imaging neuroimaging

The CB1 receptor is associated with several neuropsychiatric disorders and is an active target for in vivo imaging development (1). We recently reported that the PET radioligand 11C-MePPEP (Fig. 1) can image and quantify cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the human brain (2). This radioligand has such high and stable uptake in the brain that it can be meaningfully imaged for 210 min after injection, and receptor density can be quantified using the gold standard of compartmental modeling with an arterial input function. Nevertheless, 11C-MePPEP was limited by its short radioactive half-life (20.4 min), not because of low radioactivity in the brain but because of low radioactivity in arterial plasma by 120 min after injection. A PET radioligand using a radionuclide with a longer half-life (e.g., 18F, 109.7 min) would provide for extended measurements from arterial plasma and hopefully allow more accurate quantitation of CB1 receptors in the brain with compartmental modeling.

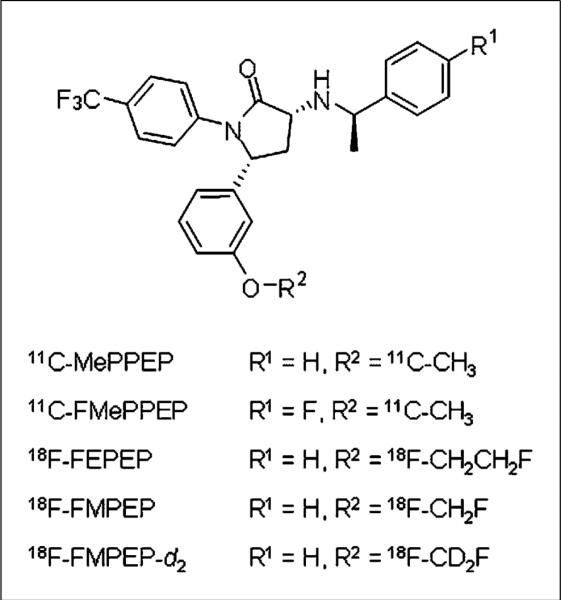

FIGURE 1.

Structure of 11C-MePPEP and its analogs.

We recently synthesized three 18F-labeled analogs of MePPEP: 18F-FEPEP, 18F-FMPEP, and 18F-FMPEP-d2 (Fig. 1) (3). The purposes of the present study were to compare the brain uptake of these 3 analogs in monkeys and evaluate the most promising candidate in humans. We found that the di-deutero fluoromethoxy analog 18F-FMPEP-d2 was the most promising candidate. Compared with MePPEP, FMPEP has a similar computed lipophilicity and similarly high selectivity for CB1 versus CB2 receptors but a slightly higher potency for CB1 receptors (the functional inhibition constant [Kb] for displacement of methanandamide is 0.47 and 0.19 nM for MePPEP and FMPEP, respectively). Fluoromethoxy groups can be defluorinated in vivo, which leads to the uptake of 18F-fluoride ion into bone. Radioactivity in the skull can contaminate the signal from the brain and artificially increase measurements. To reduce this potential problem, we substituted 2 deuteriums for the 2 hydrogens on the fluoromethoxy group. The carbon–deuterium bond is stronger than the carbon–hydrogen bonds (4), and breakage of this bond is thought to be an intermediate rate-determining step in defluorination, subject to primary isotope effect. This isotopic substitution has previously been reported to decrease the rate of defluorination in vivo successfully (5).

After evaluation in monkeys, we evaluated the ability of 18F-FMPEP-d2 to quantify CB1 receptors in the healthy human brain using compartmental modeling. The outcome measure was total distribution volume (VT), which equals the ratio at equilibrium of total radioactivity in the brain to the concentration of parent radioligand in plasma. Although VT is the sum of specific and nondisplaceable uptake, studies in monkeys showed that greater than 85% of 11CMePPEP and 18F-FMPEP-d2 is specific binding (i.e., displaceable) in the brain (6). Our initial studies of 11C-MePPEP in healthy human volunteers showed high inter-subject variability of VT, and we subsequently performed a retest study to identify the sources of variability (2). Assuming that both the clearance of 11C-MePPEP from plasma and the density of CB1 receptors in the brain were unchanged between the 2 scans, noise in the measurements of plasma radioactivity—particularly at late time points—was the likely cause of the high intersubject variability of VT. Therefore, in the current study of 18F-FMPEP-d2,we measured the retest variability of 3 parameters critical to quantify CB1 receptors in brain: clearance of the parent radioligand from plasma, assessed as the area under the curve of its concentration from time 0 to infinity (AUC0–∞); uptake of radioactivity in the brain at varying times; and VT, which itself equals the ratio of AUC0–∞ of the concentration of radioactivity in the brain to AUC0–∞ of the concentration of parent radioligand in plasma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monkey Studies

Radioligand Preparation

11C-FMePPEP, 18F-FEPEP, 18F-FMPEP, and 18F-FMPEP-d2 were synthesized as previously described (3). The specific activities at the time of injection were 284 ± 115 GBq/μmol for 11C-FMePPEP (n = 2), 150 ± 63 GBq/μmol for 18F-FEPEP (n = 4), 140 ± 12 GBq/μmol for 18F-FMPEP (n = 2), and 127 ± 93 GBq/μmol for 18F-FMPEP-d2 (n = 2). For all radioligands, the radiochemical purity was greater than 99%.

Monkey PET

Studies in monkeys were performed as described by Yasuno et al. (6), with the following deviations, in a total of 10 PET experiments in 5 male rhesus monkeys (weight, 11.6 ± 2.5 kg). Each radioligand was studied under baseline conditions and after CB1 receptor blockade (rimonabant, 3 mg/kg intravenously) 30 min before radioligand injection. Baseline and receptor-blocked studies with the 18F radioligands were performed at least 3 wk apart. Arterial blood samples were collected for all studies, except 1 baseline and 1 preblock study with 18F-FEPEP. Monkeys receiving 18F radioligands were scanned for 180 min and had additional arterial blood samples drawn at 150 and 180 min after radioligand injection. Specific binding was determined by (VT baseline – VT preblock)/VT baseline × 100%.

Human Studies

Radioligand Preparation

18F-FMPEP-d2 was prepared as previously described (3). The preparation is described in detail in our Investigational New Drug Application 100,898, submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (available at http://pdsp.med.unc.edu/snidd/). The radioligand was obtained in high radiochemical purity (>99%) and had a specific radioactivity at the time of injection of 111 ± 39 GBq/μmol (n = 17 batches).

Human Subjects

Nine healthy subjects (6 men and 3 women; mean age ± SD, 28 ± 8 y; mean body weight ± SD, 72 ± 16 kg) participated in baseline scans. Of these, 8 subjects (5 men and 3 women; mean age ± SD, 29 ± 7 y; mean body weight ± SD, 74 ± 16 kg) participated in retest scans. All subjects were free of current medical and psychiatric illness based on history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, urinalysis including drug screening, and blood tests including CBC and serum chemistries. The subjects’ vital signs were recorded before 18F-FMPEP-d2 injection and at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 180, and 240 min after injection. Subjects returned for repeated urinalysis and blood tests about 24 h after the PET scan.

Human PET

After the injection of 18F-FMPEP-d2 (180 ± 6 MBq), PET images were acquired in 3-dimensional mode with an Advance camera (GE Healthcare) for 300 min. Scans were acquired continuously up to 120 min in 33 frames of increasing duration from 30 s to 5 min, followed by three 20-min scans of four 5-min frames each, at 160, 220, and 280 min after injection. Subjects participating in the retest studies had 15–245 d between scans (mean, 81 d; median, 60 d).

Measurement of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in Plasma

Blood samples (1.5 mL each) were drawn from the radial artery at 15-s intervals until 2 min, then at 3 and 5 min, followed by 3- to 4.5-mL samples at 10, 20, 30, 60, and 90 min; 4.5- to 9-mL samples at 120, 150, and 180 min; and 12-mL samples at 210, 240, and 270 min. The plasma time–activity curve was corrected for the fraction of unchanged radioligand by radio–high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separation, as previously described (7).

The plasma free fraction of 18F-FMPEP-d2 was measured by ultrafiltration through Centrifree (Millipore) membrane filters (8). Free fractions were measured either 2 or 3 times for each sample on the same day of the PET scan. The formulation of 18F-FMPEP-d2 that was used to measure plasma free fraction did not contain polysorbate 80, which may affect plasma protein binding and whose presence would not be representative of in vivo conditions.

Image Analysis and Calculation of VT Using Metabolite-Corrected Input Function

PET images were analyzed using coregistered MR images and a standardized template as previously described (2). Regional VT and rate constants from standard 1- and 2-tissue-compartment models (9) were calculated using PMOD, version 2.95 (PMOD Technologies Ltd.) (10), with the arterial input function corrected for radiometabolites. Because of the uptake of radioactivity in the skull with 18F-FMPEP-d2, 4 regions were drawn on the coregistered MR images of each subject and applied to the PET images: combined left and right parietal bones, 9.3 ± 0.8 cm3; occiput, 24.0 ± 1.5 cm3; and clivus, 5.2 ± 1.6 cm3.

To determine the minimal scanning time necessary to obtain stable values of VT, we analyzed the PET data from each subject after removing variable durations of the terminal portion of the scan. We analyzed brain data of all subjects from 0–300 to 0–30 min, with 10-min decrements.

Statistical Analysis

Goodness of fit by the compartment models was determined as previously described (2) with F statistics (11), the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (12), and the model-selection criteria (MSC) (13). The most appropriate model is that with the smallest AIC and the largest MSC values. The identifiability of the kinetic variables was calculated as the SE, which reflects the diagonal of the covariance matrix (14). Identifiability was expressed as a percentage and equals the ratio of the SE to the rate constant itself. A lower percentage indicates better identifiability.

Group data are expressed as mean ± SD. Group analysis of brain data does not include white matter, because it does not contain significant amounts of CB1 receptors. Intersubject variability was calculated as SD divided by the mean.

The retest variability and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) were calculated as described for 11C-MePPEP in healthy subjects (2). To infer the relevance of a given ICC, we used a method to determine the statistical independence of 2 ICC values (15). We used the 2-way model to calculate the P value distinguishing ICC for VT from that of brain uptake.

RESULTS

Monkey Studies

After the injection of 11C-FMePPEP, radioactivity peaked in the brain at a standardized uptake value (SUV) of 3.3 by 30 min (Supplemental Fig. 1; supplemental materials are available online only at http://jnm.snmjournals.org) in a distribution moderately consistent with CB1 receptor distribution (Supplemental Fig. 2). VT was measured with a good identifiability (SE, 4%) and was stably measured within about 90 min using a 2-compartment model. The specific binding was determined to be 73% from the receptor-blocking experiment (Supplemental Table 1). Because 11C-FMePPEP had less brain uptake and specific binding than 11C-MePPEP in monkeys (6), we did not study this radioligand further.

After injection of 18F-FEPEP, peak radioactivity in the brain was an SUV of 2–3.5 at 15 min. VT was measured with a good identifiability (SE, 3%) and stably measured within 90 min in most regions using a 2-compartment model. The cerebellum and pons showed an increasing VT throughout the length of the scan. The specific binding was determined to be approximately 60% from the receptor-blocking experiment. SUV in the mandible reached 0.4–1.0 immediately after injection and remained the same for the duration of the scan (Supplemental Fig. 2D).

After injection of 18F-FMPEP, peak SUV in the brain was 5–6.5 at 20 min. VT was measured with a good identifiability (SE, 2%) and stably measured within about 90 min using a 2-compartment model. The cerebellum and pons showed an increasing VT throughout the length of the scan. The specific binding was determined to be approximately 90% from the receptor-blocking experiment. SUV in the mandible reached approximately 1.4 within 10 min and increased to 3.1 by the end of the 180-min scan.

After injection of 18F-FMPEP-d2, SUV peaked in the brain at 4.5–6.5 by 20 min. VT was measured with a good identifiability (SE, ~2%) and stably measured within about 90 min. The cerebellum, pons, and medial temporal cortex showed an increasing VT throughout the length of the scan. The specific binding was determined to be 80%–90% from the receptor-blocking experiment. Radioactivity concentration in the mandible reached an SUV of approximately 1.3 within 10 min and increased to 2.0 by the end of the 180-min scan.

We selected the deuterated analog 18F-FMPEP-d2 for study in human subjects because it had high brain uptake, about one third less uptake of radioactivity in bone than the nondeuterated 18F-FMPEP, and VT that was well and stably identified.

Human Studies

Pharmacologic Effects

18F-FMPEP-d2 caused no pharmacologic effects based on subjective reports, electrocardiogram, blood pressure, pulse, and respiration rate. In addition, no effects were noted in any of the blood and urine tests acquired about 24 h after radioligand injection. The injected radioactivity of 18F-FMPEP-d2 was 180 ± 6 MBq, which corresponded to 1.9 ± 0.8 nmol of FMPEP-d2 (n = 17 injections in 9 subjects). Thus, an uptake of 4 SUV in the brain would correspond to a receptor occupancy of 0.06%, assuming the maximum number of binding sites is 1.81 pmol/mg of protein in the brain (16), that 10% of brain is protein, and that all 18F-FMPEP-d2 in the brain was bound to CB1 receptors.

Radioactivity in Brain and Skull

After the injection of 18F-FMPEP-d2, all subjects showed high concentrations of radioactivity in the brain, consistent with the distribution of CB1 receptors (17), which decreased slowly over time. Radioactivity in the brain peaked by approximately 30 min and was approximately 3.2 SUV for all areas of the neocortex (Figs. 2 and 3A). Areas with high CB1 receptor density (e.g., putamen) had an even greater concentration of radioactivity, peaking over 4.0 SUV in most subjects. Radioactivity in the brain decreased slowly, remaining within approximately 85% of the peak by 2 h and within approximately 60% of the peak by = h. We averaged radioactivity concentration from 20 to 60 min after injection to represent brain uptake (brain uptake20–60; Supplemental Table 3).

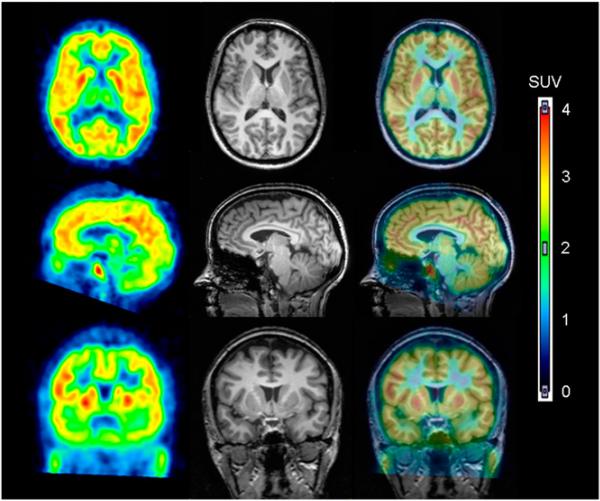

FIGURE 2.

18F-FMPEP-d2 in human brain. PET images from 30 to 60 min after injection of 18F-FMPEP-d2 were averaged (left column) and coregistered to subject's MR images (middle column). PET and MR images are overlaid in right column.

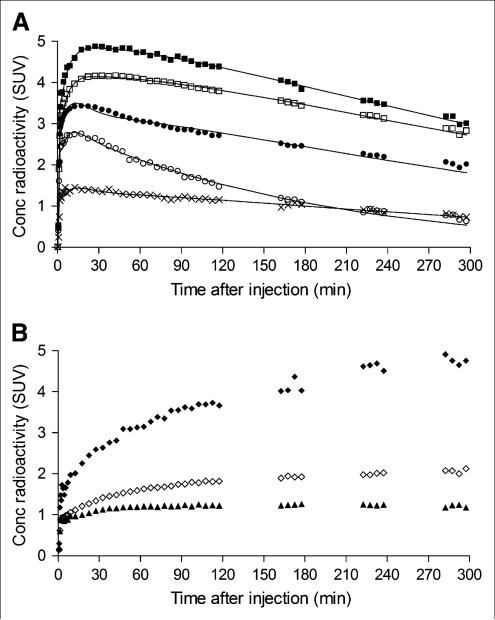

FIGURE 3.

Time–activity curves of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in brain from single subject scanned for 300 min. (A) Decay-corrected measurements from putamen (■), prefrontal cortex (□), cerebellum (•, pons (○), and white matter (×) were fitted with unconstrained 2-tissue-compartment model (–). Putamen was consistently region of highest brain uptake. White matter was consistently region of lowest brain uptake, followed by pons. (B) Decay-corrected measurements from same subject demonstrate uptake of radioactivity in clivus (◆), occiput (◇), and parietal bones (▲). Concentration (Conc) is expressed as SUV, which normalizes for injected activity and body weight.

Two regions of the brain consistently demonstrated less uptake of radioactivity than other regions. The first region, pons, had a peak SUV of approximately 2.4 within 8 min. After the peak, washout of radioactivity from the pons was 1.5–2 times faster than from other regions at 60–120 min after injection. The second region, white matter, typically peaked at an SUV of approximately 1.2 about 15 min after injection and remained nearly constant until the end of the scan, with minimal washout of radioactivity.

The skull had a significant uptake of radioactivity, which could reflect bone or marrow (Fig. 3B). Among regions of the skull, the clivus, which contains significant amounts of marrow, had the greatest uptake of radioactivity, suggesting that marrow more avidly takes up 18F-FMPEP-d2 or its radiometabolites.

Plasma Analysis

The concentration of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in arterial plasma peaked at 1–2 min and then rapidly declined because of distribution in the body, followed by a slow terminal phase of elimination. To quantify the exposure of the brain to 18F-FMPEP-d2, we fitted the concentration of 18F-FMPEP-d2 after its peak to a triexponential curve (Fig. 4A). Of the 3 associated half-lives, the first 2 (~0.4 and 5.7 min) largely reflected distribution and the last (~82 min) reflected elimination (i.e., metabolism and excretion). However, the 3 components accounted for nearly equal portions of the total AUC0-∞: approximately 18%, 28%, and 33%. The portion before the peak accounted for approximately 20% of the AUC0-∞. The concentration of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in the plasma of some subjects remained the same or slightly increased during the 2 later imaging intervals (150–180 and 210–240 min) but declined during the rest intervals (120–150, 180–210, and 240–270 min). During the rest intervals, subjects arose from the camera and walked around, suggesting that the shifting of fluid in the body may have mobilized and redistributed 18F-FMPEP-d2.

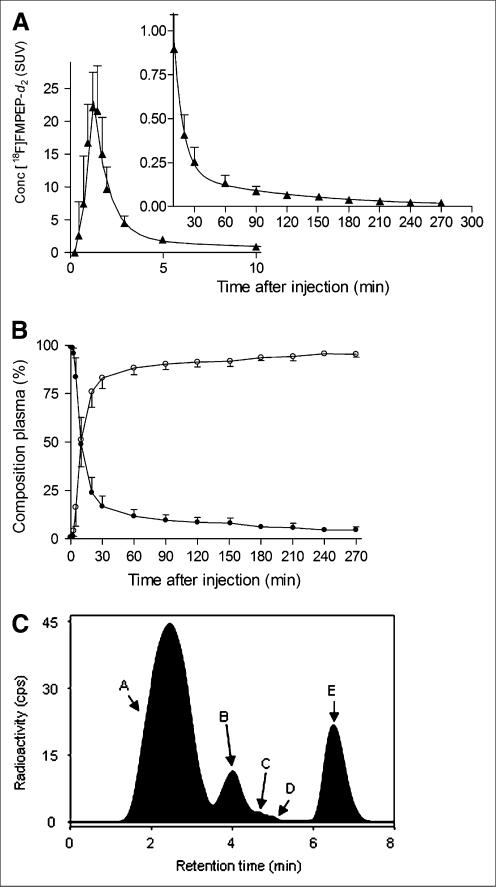

FIGURE 4.

Concentration of 18F-FMPEP-d2 and its percentage composition in arterial plasma. (A) Average concentration of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in arterial plasma from 9 subjects is plotted over time after injection. Data after peak (~1 min) were fitted to triexponential curve (—). Symbols (▲) and error bars represent mean and SD, respectively. (B) Percentage composition of parent radioligand (•) and radiometabolites (○) in arterial plasma from 9 subjects are plotted over time after injection. After 60 min, 18F-FMPEP-d2 accounted for at least 11% of radioactivity in arterial plasma. (C) This radiochromatogram illustrates plasma composition from 1 subject, 30 min after injection of 18F-FMPEP-d2. Radioactivity was measured in counts per second (cps). Peaks are labeled with increasing lipophilicity from A to E. Peak E represents 18F-FMPEP-d2. Conc = concentration.

Several radiometabolites of 18F-FMPEP-d2 appeared in plasma (Figs. 4B and 4C). The main radiometabolite eluted earlier than 18F-FMPEP-d2 on reversed-phase HPLC and was presumably less lipophilic than the parent compound. The concentration of this radiometabolite peaked within 60 min and minimally declined for the remainder of the scan. Other radiometabolites were detected throughout the scan in varying concentrations and with various elution times on HPLC. After 60 min, 18F-FMPEP-d2 constituted only 11% of total radioactivity in plasma and declined thereafter.

The free fraction of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in plasma (fP) was low. The average fP was 0.63% ± 0.33% in 9 subjects, with an SD of 0.01% for repeated sample measurements. The fP had a retest variability of 50% for 8 subjects.

Optimum Model and Scan Length for Kinetic Analysis

After 300 min of scanning, the unconstrained 2-compartment model provided a significantly better fit of the data in all subjects than did the 1-tissue-compartment model, consistent with the presence of both specific and nonspecific binding in the brain. Although the 1-tissue model estimated K1, k2, and VT with reasonable identifi-ability (SE, 1%–6%), the curves significantly deviated from the measured brain data, especially in regions with low CB1 receptor density. Compared with the 1-tissue model, the 2-tissue model had a statistically better fit to measured data by F test (P < 0.05), lower AIC scores (192 vs. 285, on average), and higher MSC scores (4.4 vs. 2.3, on average) for all brain regions.

For the 2-tissue-compartment model, we assessed the utility of constraining nondisplaceable uptake (VND = K1/k2) to a single value determined from all regions except white matter. When compared by F test, the unconstrained model fitted the data significantly better than did the constrained model in most regions, and the AIC and MSC scores favored the unconstrained model. For these reasons, we used the unconstrained 2-tissue-compartment model for additional analyses.

To determine the minimal scanning time necessary to obtain stable values of VT, we calculated VT and its identifiability using increasingly truncated durations of brain data. VT was stably identified between 60 and 120 min, whereas its identifiability was best (i.e., SE was lowest) between 120 and 300 min (Fig. 5A). VT gradually increased after 120 min, and regions closer to the skull increased more after 120 min than those in the center of the brain. Nevertheless, VT increased in all brain regions after 120 min, which was consistent with the accumulation of radiometabolites in the brain. Therefore, we chose 120 min of scan data to determine VT, because VT was stably identified between 60 and 120 min, its identifiability was good, and additional scan durations would have greater contamination from radiometabolites. We confirmed that the 2-tissue-compartment model was superior to the 1-tissue-compartment model after 120 min of data based on the same criteria described above.

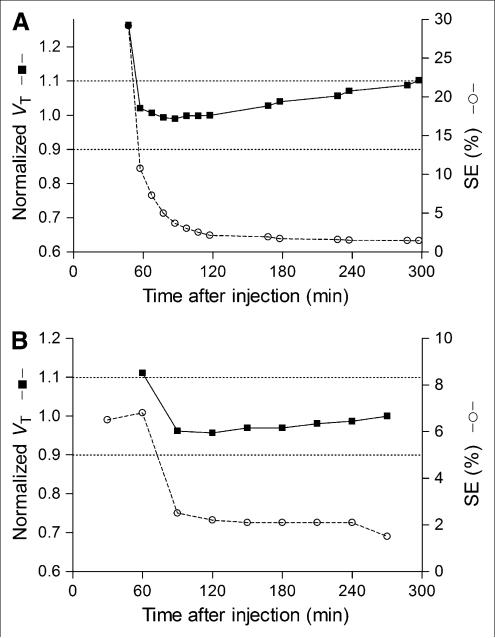

FIGURE 5.

VT of putamen and its identifiability as function of duration of image acquisition (A) and plasma measurements (B). VT (■) was calculated using unconstrained 2-tissue-compartment model. Values were normalized to that determined from 120 min of imaging and are plotted with y-axis on left. Corresponding SE (○), which is inversely proportional to identifiability, is plotted with y-axis on right. Points represent average of 9 subjects. (A) Length of image acquisition was varied from 0–30 to 0–300 min, but entire input function (0–270 min) was used for all calculations. VT was stably identified between 60 and 120 min but gradually increased thereafter. (B) Length of plasma input function was varied from 0–270 to 0–60 min, but initial 120 min of image acquisitions were used for all calculations. VT was stably identified with as little as initial 90 min of plasma data.

Kinetic Analysis and Retest Variability Based on 120 min of Scan Data

The value of K1 in all regions except white matter ranged from 0.08 to 0.12 mL cm–3·min–1, with an average of 0.10 mL·cm–3·min–1 (Supplemental Table 2). Assuming that cerebral blood flow is approximately 0.5 mL·cm–3·min–1, the extraction fraction (extraction = K1/flow) of 18F-FMPEP-d2 from plasma to brain was approximately 20%. The value of k2 in all regions except white matter ranged from 0.04 to 0.06 min–1, with an average of approximately 0.06 min–1. Thus, the value of nondisplaceable VT (VND = K1/k2) was approximately 2.0 mL·cm–3. The value of k3, which is defined as kon·Bmax·fND, ranged from 0.085 to 0.143 min–1, with an average value of approximately 0.112 min–1. The value of k4, which is proportional to the dissociation rate constant from the specific compartment, was low and ranged from 0.010 to 0.027 min–1, with an average of approximately 0.018 min–1. Finally, the estimated ratio of specific to nondisplaceable uptake (BPND = k3/k4) was approximately 7.3 in the healthy human brain.

Retest variability for 18F-FMPEP-d2 was moderate to good (Supplemental Table 3). The mean retest variability of brain uptake20–60 and VT was 16% and 14%, respectively. However, the ICC of VT (0.89) was significantly better than that of brain uptake (0.39, P < 0.03). Finally, the retest variability of the plasma measurements alone was approximately 16%, as assessed by AUC0-∞.

The intersubject variability for VT of 18F-FMPEP-d2 was moderate (~26%; Supplemental Table 2) and was greater than both the retest variability of 18F-FMPEP-d2 and the intersubject variability reported for other radioligands (10%–20%). The intersubject variability was lower for brain uptake20–60 (~14%) than for VT. The intersubject variability of the plasma measurements was also good, 20%, assessed as AUC0-∞.

The intersubject variability of VT might have been affected by variations in the plasma free fraction of 18F-FMPEP-d2. However, the intersubject variability of VT/fP in all 8 brain regions of the 9 subjects scanned for 120 min was actually higher than that of VT and ranged from 40% to 60%. The retest variability of VT/fP was also higher, again ranging from 40% to 60%, indicating that VT/fP has less precision than did VT alone. Indeed, the retest variability of free fraction itself was approximately 50%. Thus, correction of VT for individual values of plasma protein binding increased intersubject and retest variability and was likely a source of noise to the data.

To determine the minimal length of blood sampling required to measure VT, we truncated the plasma data in a manner similar to the brain data (Fig. 5B). When plasma data were truncated from 270 to 120 min, plasma AUC0-∞ changed by only approximately 4% and VT changed by only approximately 4%. Thus, plasma AUC0-∞ and VT were well identified with this initial 120 min of plasma data.

Can Brain Uptake Substitute for VT?

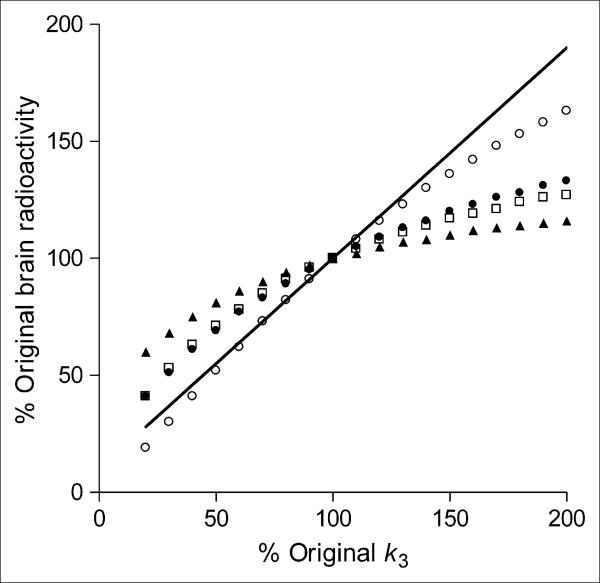

Brain uptake not corrected for plasma measurements has been used with another radioligand to measure CB1 receptor availability in the human brain (18,19). With 11C-MePPEP, we found that the intersubject variability and retest variability of brain uptake was much better than that of VT. In contrast, brain uptake and VT for 18F-FMPEP-d2 showed similar intersubject variability and retest variability. Similar to 11C-MePPEP, we sought to determine whether brain uptake by itself would be a reasonably accurate surrogate for VT and thereby avoid plasma measurements. We simulated increased and decreased receptor densities by corresponding changes in k3. We used the average input function and rate constants for prefrontal cortex from the 9 subjects scanned for 120 min. Brain uptake was calculated for 4 time intervals: 20–60, 90–120, 280–300, and 0–300 min.

Brain uptake for all time intervals except 280–300 min followed the pattern of increasing or decreasing receptor density but underestimated the changes (Fig. 6). For example, a 50% increase in receptor density yielded a 10%–20% increase only of brain uptake during the time intervals 20–60, 90–120, and 0–300 min, whereas VT increased by 45%. VT includes both specific and nondisplaceable uptake; thus, a 50% increase of k3 and specific binding causes a 45% increase only of VT. In addition, a 50% decrease in receptor density yielded a 19%–31% decrease only of brain uptake during these 3 time intervals, whereas VT decreased by 45%. For simulations of brain uptake from 280 to 300 min, a 50% increase in receptor density yielded a 36% increase of brain uptake, whereas a 50% decrease in receptor density yielded a 48% decrease of brain uptake. This suggests that brain uptake280–300 might accurately predict changes in receptor density. However, these simulations were performed with kinetic parameters attained after 120 min; later values of brain uptake may be contaminated by radiometabolites or radioactivity accumulating in the skull, decreasing the accuracy of these measurements.

FIGURE 6.

Simulated changes in brain uptake with variations of receptor density. Average individual kinetic parameters from prefrontal cortex were used to simulate expected changes in brain uptake at 280–300 (○), 0–300 (•), 90–120 (□), and (▲) 20–60 min. Changes in receptor density were simulated by varying value of k3 from its mean value (set at 100% on x-axis). As expected, value of VT (shown by line that has y-intercept equal to K1/k2) is directly proportional to changes in k3.

We also calculated the expected number of subjects needed to detect these simulated outcome measurements. Estimation of sample sizes for a 2-tailed t test assumed α = 0.05 (probability of type I error) and β = 0.20 (probability of type II error, that is, power of 80%). Intersubject variability from our measurements from 9 subjects was used to estimate the pooled SD of the 2 outcome measures: brain uptake and VT. For a 50% increase of receptor density, 39 subjects would be required for brain uptake20–60 versus 7 subjects for VT. Additionally, for a 50% decrease of receptor density, 12 subjects would be required for brain uptake20–60 versus 7 subjects for VT.

DISCUSSION

This initial evaluation of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in healthy human subjects demonstrated that cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the brain can be measured as VT with good identifiability and precision and low retest variability. We recommend scanning for 60–120 min, with intermittent sampling of arterial blood to measure the parent radioligand in plasma. Scanning for more than 120 min is problematic for 2 reasons. First, the apparent value of VT gradually increased during the interval from 120 to 300 min, suggesting that radiometabolites were accumulating in the brain. Second, radioactivity significantly accumulated in the skull during this same period, and spillover of activity would have contaminated measurements in adjacent brain. 18F-FMPEP-d2 is superior to 11C-MePPEP largely because the longer-lived radioactivity permits greater accuracy and reproducibility of measurements, particularly for those from plasma. Finally, measurements of brain uptake alone, compared with VT, are inaccurate. Brain uptake underestimates changes in receptor density and requires larger sample sizes than VT to detect significant differences between groups.

Accumulation of Radioactivity in Skull

We compared three 18F-labeled analogs in monkeys and selected 18F-FMPEP-d2 to study in humans because it had high uptake in the brain and one third less uptake of radioactivity in the skull than 18F-FMPEP. Skull uptake can reflect in vivo defluorination and subsequent accumulation of 18F-fluoride ion in bone. Despite our use of a dideuterated analog to decrease defluorination, 18F-FMPEP-d2 did yield substantial radioactivity uptake in the human skull, especially during the period from 120 to 300 min. We do not know whether the uptake in skull was in bone versus marrow or whether it was due to parent radioligand or radiometabolite. Nevertheless, to what extent did accumulation in the skull before 120 min confound measurements of VT? To answer this question, we simulated the spillover based on resolution of the camera and the distance between skull and adjacent brain regions. We used conservative assumptions that would tend to overestimate spillover. Specifically, we assumed that the images had a resolution of 10 mm in full width at half maximum, that the cerebral cortical region was 10 mm wide, that the skull was 8 mm thick, that skull and cortex were separated by 5 mm, and that SUV was 2.4 in cortex and 1.7 in bone, which reflect measured values at 120 min. Using these conservative parameters, we estimated that radioactivity from the skull constituted only about 2% of measurements in adjacent cortex. Thus, contamination of neocortical activity from that in skull was negligible during the initial 120 min, which itself was adequate to provide well and stably identified values of VT.

Comparison of 18F-FMPEP-d2 to 11C-MePPEP

The brain uptake of 18F-FMPEP-d2 and 11C-MePPEP are fairly similar in the human brain (Supplemental Table 4). High and prolonged uptake allows 11C-MePPEP to provide useful measures of brain radioactivity for 210 min, which we extended using the longer radioactive half-life with 18F-FMPEP-d2. 18F-FMPEP-d2 also tended to peak earlier and wash out faster than 11C-MePPEP. Perhaps the most important difference between the 2 radioligands is the lower accuracy of plasma measurements for 11C-MePPEP than for 18F-FMPEP-d2. For example, the retest variability of plasma AUC0-∞ was 58% for 11C-MePPEP and 16% for 18F-FMPEP-d2. The relatively high retest variability of plasma AUC0-∞ for 11C-MePPEP was likely the cause of larger intersubject variability of VT for 11C-MePPEP than for 18F-FMPEP-d2. The greater accuracy of the plasma concentration measurements of 18F-FMPEP-d2 was also reflected in the stability of VT determined by increasingly truncating the plasma curve. Measurements from plasma attained at 90 min after injection were approximately as good for defining both the input function and the VT as measurements from the entire 270 min of plasma data (Fig. 5B). We attribute this consistency between 90 and 270 min to the precision with which we were able to measure the input function, which in turn facilitated our precise measurements of VT.

This retest analysis assumes that plasma clearance and receptor density in the brain were the same for both scans. The comparison of the 2 radioligands may be biased against 18F-FMPEP-d2, because the 2 scans for 11C-MePPEP were done on the same day (morning and afternoon), whereas the interval between scans for 18F-FMPEP-d2 was 15–245 d. Although the retest variability of VT was similar for both radioligands, 18F-FMPEP-d2 had a superior ICC, meaning that it is better able to distinguish between-subject from within-subject differences. Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the primary advantage of 18F-FMPEP-d2 over 11C-MePPEP is the greater accuracy of the plasma measurements, which leads to greater accuracy of VT and smaller sample sizes needed to detect differences between groups.

CONCLUSION

This initial evaluation of 18F-FMPEP-d2 in healthy human subjects showed that brain uptake and unchanged parent radioligand in plasma provide robust measurements of VT, which is an index of receptor density. The scanning time should be no more than 120 min, because longer acquisitions are vulnerable to contamination of the brain with radiometabolites and spillover of radioactivity from the skull. Retest analysis shows that 18F-FMPEP-d2 has greater precision and accuracy than 11C-MePPEP and will allow smaller sample sizes to detect significant differences between groups (e.g., patients vs. healthy subjects).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. 11C-FMePPEP, 18F-FEPEP, 18F-FMPEP, or 18F-FMPEP-d2 in monkey. Time-activity curves were acquired under baseline conditions (open symbol) and 30 min after administration of rimonabant (3 mg/kg, i.v.; closed symbol). (A) 11C-MePPEP (◇) is shown as a comparison to 11C-FMePPEP (△), and (B) 18F-FEPEP (▽), 18F-FMPEP (□), and 18F-FMPEP-d2 (○) in monkey striatum. (C) Distribution volume (VT) for 11C-FMePPEP (△), 18F-FEPEP (▽), 18F-FMPEP (□), and 18F-FMPEP-d2 (○) was calculated using an unconstrained two-tissue compartment model with 0-30 or 0-180 min of data. (D) Radioactivity concentration in monkey bone was greatest in 18F- FMPEP (□), followed by 18F-FMPEP-d2 (○) and 18F-FEPEP (▽).

Supplemental Figure 2. 11C-FMePPEP, 18F-FEPEP, 18F-FMPEP, or 18F-FMPEP-d2 in monkey brain. Axial PET images of monkey brain from 60 to 120 minutes after injection of (A) 11C-FMePPEP and 120 to 180 after injection of (B) 18F-FEPEP, (C) 18F-FMPEP, and (D) 18F-FMPEP-d2 were averaged after baseline conditions (top row) and after pretreatment of rimonabant (3 mg/kg i.v.; bottom row). (E) A representative monkey MRI is provided for reference.

Supplemental Table 1. Distribution volume of several CB1 selective radioligands in monkey brain

Supplemental Table 2. Kinetic rate constants and distribution volume (VT) in 8 regions of brain from 9 subjects using 120 min of scanning data

Supplemental Table 3. Brain uptake and distribution volume (VT) in regions of brain from 8 subjects using 120 min of data

Supplemental Table 4. Comparison of 11C-MePPEP and 18F-FMPEP-d2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Pavitra Kannan, Kimberly Jenko, and Kacey Anderson for measurements of radioligand in plasma; Yi Zhang for preparation of 18F-FMPEP-d2; Maria D. Ferraris Araneta, William C. Kreisl, and Barbara Scepura for subject recruitment and care; the NIH PET Department for imaging; and PMOD Technologies for providing its image analysis and modeling software. This research was supported by a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement with Eli Lilly; by the Intramural Program of NIMH (projects Z01-MH-002852-04 and Z01-MH-002793-06); and grants from the Academy of Finland, the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, the Finnish Medical Foundation, the Instrumentarium Foundation, the Jalmari and Rauha Ahokas Foundation, the Paulo Foundation, the Research Foundation of Orion Corporation, and the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Van Laere K. In vivo imaging of the endocannabinoid system: a novel window to a central modulatory mechanism in humans. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1719–1726. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0505-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terry GE, Liow JS, Zoghbi SS, et al. Quantitation of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in healthy human brain using positron emission tomography and an inverse agonist radioligand. Neuroimage. 2009;48:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.06.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donohue SR, Krushinski JH, Pike VW, et al. Synthesis, ex vivo evaluation, and radiolabeling of potent 1,5-diphenylpyrrolidin-2-one cannabinoid subtype-1 receptor ligands as candidates for in vivo imaging. J Med Chem. 2008;51:5833–5842. doi: 10.1021/jm800416m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hashimoto K, Inoue O, Suzuki K, Yamasaki T, Kojima M. Deuterium isotope effect of [11C1]N,N-dimethylphenethyl-amine-a,a-d2; reduction in metabolic trapping rate in brain. Int J Rad Appl Instrum B. 1986;13:79–80. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(86)90256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schou M, Halldin C, Sovago J, et al. PET evaluation of novel radiofluorinated reboxetine analogs as norepinephrine transporter probes in the monkey brain. Synapse. 2004;53:57–67. doi: 10.1002/syn.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasuno F, Brown AK, Zoghbi SS, et al. The PET radioligand [11C]MePPEP binds reversibly and with high specific signal to cannabinoid CB1 receptors in nonhuman primate brain. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:259–269. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zoghbi SS, Shetty HU, Ichise M, et al. PET imaging of the dopamine transporter with 18F-FECNT: a polar radiometabolite confounds brain radioligand measurements. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:520–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gandelman MS, Baldwin RM, Zoghbi SS, Zea-Ponce Y, Innis RB. Evaluation of ultrafiltration for the free-fraction determination of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) radiotracers: β-CIT, IBF, and iomazenil. J Pharm Sci. 1994;83:1014–1019. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600830718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burger C, Mikolajczyk K, Grodzki M, Rudnicki P, Szabatin M, Buck A. JAVA tools for quantitative post-processing of brain PET data [abstract]. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(suppl):277P. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawkins RA, Phelps ME, Huang S-C. Effects of temporal sampling, glucose metabolic rates, and disruptions of the blood-brain barrier on the FDG model with and without a vascular compartment: studies in human brain tumors with PET. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1986;6:170–183. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1986.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita M, Imaizumi M, Zoghbi SS, et al. Kinetic analysis in healthy humans of a novel positron emission tomography radioligand to image the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor, a potential biomarker for inflammation. Neuroimage. 2008;40:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carson RE, Huang SC, Green MV. Weighted integration method for local cerebral blood flow measurements with positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1986;6:245–258. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1986.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGraw KO, Wong SP. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abood ME, Ditto KE, Noel MA, Showalter VM, Tao Q. Isolation and expression of a mouse CB1 cannabinoid receptor gene: comparison of binding properties with those of native CB1 receptors in mouse brain and N18TG2 neuroblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1997;53:207–214. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00727-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass M, Dragunow M, Faull RL. Cannabinoid receptors in the human brain: a detailed anatomical and quantitative autoradiographic study in the fetal, neonatal and adult human brain. Neuroscience. 1997;77:299–318. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00428-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burns HD, Van Laere K, Sanabria-Bohorquez S, et al. [18F]MK-9470, a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer for in vivo human PET brain imaging of the cannabinoid-1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9800–9805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703472104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Laere K, Goffin K, Casteels C, et al. Gender-dependent increases with healthy aging of the human cerebral cannabinoid-type 1 receptor binding using [18F]MK-9470 PET. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1533–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. 11C-FMePPEP, 18F-FEPEP, 18F-FMPEP, or 18F-FMPEP-d2 in monkey. Time-activity curves were acquired under baseline conditions (open symbol) and 30 min after administration of rimonabant (3 mg/kg, i.v.; closed symbol). (A) 11C-MePPEP (◇) is shown as a comparison to 11C-FMePPEP (△), and (B) 18F-FEPEP (▽), 18F-FMPEP (□), and 18F-FMPEP-d2 (○) in monkey striatum. (C) Distribution volume (VT) for 11C-FMePPEP (△), 18F-FEPEP (▽), 18F-FMPEP (□), and 18F-FMPEP-d2 (○) was calculated using an unconstrained two-tissue compartment model with 0-30 or 0-180 min of data. (D) Radioactivity concentration in monkey bone was greatest in 18F- FMPEP (□), followed by 18F-FMPEP-d2 (○) and 18F-FEPEP (▽).

Supplemental Figure 2. 11C-FMePPEP, 18F-FEPEP, 18F-FMPEP, or 18F-FMPEP-d2 in monkey brain. Axial PET images of monkey brain from 60 to 120 minutes after injection of (A) 11C-FMePPEP and 120 to 180 after injection of (B) 18F-FEPEP, (C) 18F-FMPEP, and (D) 18F-FMPEP-d2 were averaged after baseline conditions (top row) and after pretreatment of rimonabant (3 mg/kg i.v.; bottom row). (E) A representative monkey MRI is provided for reference.

Supplemental Table 1. Distribution volume of several CB1 selective radioligands in monkey brain

Supplemental Table 2. Kinetic rate constants and distribution volume (VT) in 8 regions of brain from 9 subjects using 120 min of scanning data

Supplemental Table 3. Brain uptake and distribution volume (VT) in regions of brain from 8 subjects using 120 min of data

Supplemental Table 4. Comparison of 11C-MePPEP and 18F-FMPEP-d2