Abstract

Origins of mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about infant crying were examined in 87 couples. Parents completed measures of emotion minimization in the family of origin, depressive symptoms, empathy, trait anger, and coping styles prenatally. At 6 months postpartum, parents completed a self-report measure of their beliefs about infant crying. Mothers endorsed more infant-oriented and less parent-oriented beliefs about crying than did fathers. Consistent with prediction, a history of emotion minimization was linked with more parent-oriented and fewer infant-oriented beliefs about infant crying for both mothers and fathers either as a main effect or in conjunction with the partners’ infant-oriented beliefs. Contrary to expectation, parents’ own emotional dispositions had little effect on parents’ beliefs about crying. The pattern of associations varied for mothers and fathers in a number of ways. Implications for future research and programs promoting sensitive parenting are discussed.

Keywords: Parental beliefs, infants, crying, family of origin, parental sensitivity

Parents’ beliefs about crying are important predictors of their behavioral responses such that parents who endorse flexible and infant- oriented beliefs respond more quickly and sensitively to infant crying (Crockenberg & McCluskey, 1986; Leerkes, in press; Zeifman, 2003). Prompt and sensitive responding to infant distress is in turn linked with infants’ subsequent attachment security, adaptive emotion regulation, social competence, and fewer behavioral problems independent of sensitive responding to non-distress (Leerkes, Blankson, & O’Brien, 2009; McElwain & Booth-LaForce, 2006). However, little is known about the origins of parents’ beliefs about why infants cry, why they respond the way they do to crying, and whether they believe their responses have a long-term impact on their developing infants. Such information is important because it may shed light on the mechanisms that explain the continuation of parenting beliefs and practices across generations, be used to develop screening tools to identify families at risk for insensitive parenting, and inform the education efforts aimed at promoting sensitive responding to infant distress. Thus, the purpose of this paper is to identify the origins of mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about crying. The factors under consideration include the extent to which parents’ negative emotions were minimized by their own parents in childhood, their partners’ beliefs about crying, and their emotional dispositions (i.e., trait empathy and anger, depressive symptoms, and coping styles).

Parents’ Beliefs About Crying and Links with Parental Behavior

Parental beliefs include parents’ knowledge about child development and the nature of their child, beliefs about parenting strategies and self as parent, and parenting goals, each of which is believed to influence parental behavior (Dix, 1992; Sigel & McGillicuddy-DeLisi, 2002). For example, parents who believe infants cry to be manipulative rather than to communicate a need may be more inclined to ignore crying in an effort to prevent their infant from becoming “spoiled.” Parenting beliefs have been categorized based on whose needs are emphasized based on the view that prioritizing child needs prompts more sensitive or supportive parenting than prioritizing parent needs (Dix, 1992). Child-oriented beliefs prioritize children’s needs, desires, and well-being (e.g., I want my child to be safe), which should prompt protective and comforting responses to crying. In contrast, parent-oriented beliefs prioritize parents’ needs and well-being (e.g., I want my child to stop crying because it bothers me), which should prompt negative, intrusive, or withdrawal responses to crying. This distinction has been successfully applied to a variety of parenting domains. Child-focused beliefs have been linked to parents’ use of reasoning during parent-child disagreements, structuring and support in response to child aggression, and nurturance and reasoning during compliance tasks among preschool and school aged children (Hastings & Grusec, 1998; Hastings & Rubin, 1999; Kuczynski, 1984).

Within the realm of emotion socialization during infancy, mothers with infant-oriented beliefs about crying responded more sensitively to infant distress (Crockenberg & McCluskey, 1986; Leerkes, in press; Leerkes, Crockenberg, & Burrous, 2004), whereas adults with parent-oriented, negative beliefs about crying reported they would wait longer before intervening when an infant was crying (Zeifman, 2003). Among parents of older children, accepting/valuing beliefs about children’s negative emotions were linked with encouraging children to display their negative emotions (Wong, Diener, & Isabella, 2008). Acceptance of beliefs about negative emotions was also linked with discussing the events of September 11, a salient emotional event, with children (Halberstadt, Thompson, Parker, & Dunsmore, 2008). In contrast, parent-centered goals were linked with dismissing child negative emotions (Lagacé-Séguin & Coplan, 2005). Given these links between parents’ beliefs about emotions and their behavior in response to child emotions, which is in turn linked with a variety of adaptive child outcomes (see Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998 for a review), identifying the origins of these beliefs may be important from an intervention perspective.

Origins of Parents’ Beliefs About Crying

Sigel and McGillicuddy-DeLisi (2002) laid out eight key propositions about parenting beliefs in their dynamic belief systems model. Two are relevant to the origins of beliefs, and the others focus on links between beliefs and behavior. Those relevant to the origins of beliefs are that beliefs are: 1) knowledge based and derived from the construction of relevant experiences and 2) influenced by affect. Drawing from these propositions, we argue that the manner in which ones’ own emotions were responded to in childhood and their partners’ beliefs about infant crying are important sources of knowledge about crying. Further, parents’ affective qualities, or emotional dispositions, influence their beliefs about the significance of and appropriate way to respond to infant crying, as well as their ability to focus on their infants’ versus their own needs. Below, we elaborate on the mechanisms linking these factors to parents’ beliefs about crying.

Parents and Partners as a Source of Knowledge and Beliefs

The manner in which parents’ emotional needs were met in childhood likely affect their beliefs about infant crying because views about development are passed from generation to generation (Harkness, Super, & Keefer,1992). This suggests direct main effects whereby adults whose own emotions were punished, ignored, or ridiculed in childhood are likely to have parent-oriented beliefs about crying and how to respond to crying. They may, for example, believe that children cry just for attention and that the best response is to ignore them either because their parents stated these beliefs or because they inferred them from their parents’ behavior. Consistent with this view, being spanked in childhood is linked with greater endorsement of spanking among adults (Holden & Zambarano, 1992), and mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behavior predicted their children’s discipline beliefs, although associations tended to be stronger for male children than female children (Simons, Beaman, Conger, & Chao, 1992).

It is also likely that partners’ beliefs about parenting are correlated for two reasons. First, adults with similar beliefs may seek each other out during mate selection (Botwin, Buss, & Shackelford, 1997). Second, parenting partners may influence one another over time as they discuss their parenting beliefs or observe one another’s parenting behaviors. Previously reported positive correlations between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting beliefs within a variety of domains support this view (Holden & Zambarano, 1992; Wong et al., 2008).

It is also possible that parents’ emotion relevant behavior and the partners’ beliefs about crying have a joint effect on beliefs about crying. That is, some adults whose emotions were minimized in childhood may view this as having been a negative experience in their childhood and actively avoid similar experiences with their children (Harkness et al., 1992). One factor that may affect how adults make meaning of their prior experiences with negative emotions in relation to their own beliefs about infant crying is their partners’ beliefs about crying, which may operate as a buffer from the inheritance of negative beliefs about crying from the previous generation. As couples parent their children jointly, the positive parenting characteristics of one partner may influence the other. That is, an adult whose emotions were minimized in childhood but has a parenting partner with infant-oriented beliefs may be motivated to be different from their parents, have access to positive examples of how to do so, and receive support to change, all of which could enhance their infant-oriented beliefs about crying despite a negative personal history with emotions (Leerkes & Crockenberg, 2006).

Parents’ Emotional Dispositions

It is highly likely that parents’ own emotional dispositions influence their beliefs about infant crying also. Adults who experience elevated symptoms of depression report that infant crying is less urgent and arousing, and are less likely to say they would intervene than non-depressed adults (Schuetze & Zeskind, 2001) suggesting that depression is linked with less of an infant-orientation. Likewise, adults that are prone to anger may be unable to focus on infant needs as suggested by links between the trait of parental anger and negative attributions about children and the endorsement of highly punitive parenting practices (Dix, Reinhold, & Zambarano, 1990; Lutenbacher, 2002). In contrast, trait empathy (i.e., the tendency to respond to another person’s affect with congruent affect based on an understanding of that person’s situation or condition; Eisenberg & Miller, 1987) should enhance a parents’ ability to recognize and prioritize their infants’ needs when they cry. Consistent with this view, empathy has been linked with the desire to help others for other-oriented rather than self-oriented reasons and with sensitive parenting (Kochanska, Friesenborg, Lange, & Martel, 2004; Reizer & Mikulincer, 2007).

The manner in which parents cope with negative emotions and stress also likely influences their beliefs about infant crying. Although there is debate about the measurement and structure of coping strategies (Skinner, Edge, Altman, & Sherwood, 2003), a distinction that has yielded useful results in the past is between engaged and disengaged or avoidant coping. Engaged coping includes behaviors that focus on the source of stress and related thoughts and feelings, whereas disengaged/avoidant coping includes responses aimed at orienting away from the stressor and affiliated negative affect. Avoidant strategies are related to increased psychological distress (Besser & Priel, 2003), and are particularly maladaptive when used by adults in response to stressors that are somewhat controllable (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Previous work with primiparous mothers suggests that parents whose primary strategy is to avoid stressful situations, and the negative emotions they elicit, likely endorse parent-oriented beliefs aimed at minimizing crying and contact with their distressed infant (Leerkes & Crockenberg, 2006). In this previous work, indicators of an avoidant coping style were negatively associated with mothers’ infant focused emotion goals.

Patterns of associations in other studies suggest that these emotional dispositions may mediate the association between a childhood history of emotion minimization and beliefs about infant crying. That is, adults whose emotions were minimized in childhood may be more emotionally labile and uncomfortable with negative emotions because they were viewed as undesirable, and they may struggle to control their emotions because they had few opportunities to learn to appropriately express and regulate negative emotions in childhood and received limited parental support for their efforts to do so. Consistent with this view, a history of harsh parenting or emotional rejection is linked with greater trait-anger among college students (Hoglund & Nicholas, 1995), to more depressive symptoms in young parents (Gotlib, Mount, Cordy, & Whiffen, 1988), to less empathy in a study extending into adulthood (Koestner, Franz, & Weinberger, 1990), and more avoidant coping styles in young adolescents (Meesters & Muris, 2004). In turn, anger, depression, low empathy, and avoidant coping are linked with parent-oriented beliefs and behavior, as elaborated above. These associations support the view that the effect of childhood emotion minimization on beliefs about crying is mediated by emotional dispositions.

The Present Study

In sum, the purpose of this study is to identify the predictors of mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about infant crying. Two features distinguish this study from previous research. First, the inclusion of both mothers and fathers is a strength because less research has been conducted on paternal belief systems and the inclusion of both allows us to examine the extent to which mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs are related and the extent to which they and their origins differ. Second, all predictors were measured during the prenatal period ruling out the possibility that infant characteristics or parenting experience could have influenced them. We test the following hypotheses: 1) a childhood history of emotion minimization, trait anger, depression, and avoidant coping will correlate positively with parent-oriented beliefs and negatively with infant-oriented beliefs about crying; the opposite pattern is predicted for empathy. And within the same family mothers’ and fathers’ parallel beliefs about crying will correlate positively; 2) the effect of childhood history of emotion minimization on parents’ beliefs about crying will be mediated via their emotional dispositions (empathy, anger, depression, and avoidant coping styles); and 3) the association between a childhood history of emotion minimization and beliefs about infant crying will be moderated (i.e., buffered) by partners’ infant-oriented beliefs about crying. Specifically, emotion minimization will be linked with more parent-oriented and less infant-oriented beliefs about crying only among parents whose partners do not endorse infant-oriented beliefs about crying.

We propose the same pattern of associations for mothers and fathers, but it is important to acknowledge that the extent to which different factors predict mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about crying may vary for several reasons. For example, as fathers tend to have less prior direct experience with children to draw from than mothers (Parke, 2002), they may be more influenced by their childhood experiences with their own parents and by what their partners do, say, and believe in regards to parenting as they may perceive their wives/partners as more expert in childrearing. There may also be mean difference in mothers’ and father’ beliefs about crying. As new fathers’ describe feeling in competition with their new infant for their wives/partners’ attention (Belsky & Kelly, 1994), a feeling that seems particularly likely in the context of infant crying as it is such a salient bid for mothers’ attention, they may be prompted to have more self-focused beliefs about crying (e.g., it is good for my baby to cry it out). Thus, we examine mean differences in mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about crying and compare their predictors.

Method

Participants

Approximately 300 hundred expectant mothers contacted via childbirth education classes consented to hearing more about the study via a phone call. Of these, 120 (40%) primiparous mothers participated in a larger longitudinal study about the origins of maternal sensitivity. Participating mothers were asked to invite their partners to participate as well. Given the goals of this manuscript, only families for whom both mother and father data were available were included in the analytic sample (87 couples). That is 11 mothers were excluded because they were single mothers and 22 mothers were excluded because their partners chose not to participate. Mothers excluded from the analytic sample were more likely to be non-White (χ2(1) = 12.45, p < .01), were younger (t(118) = 4.19, p < .01), had fewer years of education (t(118) = 4.13, p < .01), and lower family incomes (t(118) = 4.25, p < .01) than included mothers. However, the two groups did not differ on any of the primary variables of interest, except depressive symptoms, which were higher among mothers for whom no partner data was available, (t(118) = 2.60, p <.01). Importantly, the mother analyses were conducted both with and without these mothers; the results did not vary.

In the analytic sample, mothers’ age ranged from 20 to 37 (M = 28.95), education ranged from less than a high school diploma to a graduate degree (34% did not have a 4 year college degree), and 85% of mothers were White, 12% were Black, 2% were Asian-American, and 1% were Hispanic non-White. Fathers’ age ranged from 21 to 43 (M = 30.98), education ranged from less than a high school diploma to a graduate degree (36% did not have a 4 year college degree), and 81% of fathers were White, 15% were Black, and 5% did not disclose their race. Ninety-eight percent of couples were married or cohabitating and 2% were dating. Family income ranged from $18,000 to $190,000 (median = $65,000). All infants were full-term and healthy and 54 were male. Mothers were the primary caregivers in the majority of families.

Procedure

Mothers were contacted through local birthing classes during the last trimester of pregnancy. When mothers indicated they had a partner, we invited them to ask their partner to participate as well. Interested parents were mailed consent forms and measures of demographics, childhood emotion minimization, depressive symptoms, coping styles, empathy, and trait anger. Mothers returned all completed forms when they visited the Family Observation Room on campus for a prenatal interview that was part of the larger study. At 6 months postpartum, parents were mailed a measure about their beliefs about infant crying, and mothers returned them when they visited the Family Observation Room with their infants for an observation and interview as part of the larger study. Participating families received gift cards. Procedures were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Childhood emotion minimization

During the prenatal period, parents completed a measure of emotion socialization in the family of origin adapted from the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Parker, Tupling, & Brown, 1979). The measure included 9 items that assessed the degree to which negative emotions were ignored, minimized, ridiculed, and punished by their mothers and fathers during their first 16 years of life (e.g., ignored me when I was upset, got annoyed with me when I was sad). Participants rated how well each item described their parents on a scale ranging from very unlike (1) to very like (4). Items were averaged to derive scores of remembered emotion minimization by mothers and by fathers, Cronbach’s α = .78 and .82 for mothers’ reports and .75 and .76 for fathers’ reports of their mothers and fathers respectively. The original PBI correlated with the respondents’ mothers’ self-reports of parenting behavior (Parker, 1981) supporting the validity of retrospective reports of parenting. Participants’ ratings of their mothers and fathers correlated highly, r = .68 for mothers’ and r = .67 for fathers’ reports of their parents. These were averaged to yield scores that reflect the extent to which respondents felt both of their parents responded negatively to their emotions during childhood.

Global empathy

Parents completed the empathic concern and perspective taking subscales, 7 items each, of the Interpersonal Reactivity Scale (Davis, 1983) prenatally. Respondents rated how well each statement described them on a scale ranging from does not describe me (1) to describes me very well (5). These subscales had good internal and test-retest reliability, and correlated positively with other empathy scales (Davis). Items were averaged to yield a single measure of global empathy (α = .82 and .83 for mothers and fathers).

Trait anger

Parents completed the 10 item trait anger subscale of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (Spielberger, 1988) during the prenatal period. Participants rated how frequently they tend to feel and express anger on 4-point scale ranging from almost never to almost always. Items were averaged such that higher scores indicate greater trait anger, Chronbach’s α = .85 and .86 for mothers and fathers respectively.

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed prenatally using the 20 item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977) which assesses moods, feelings, and cognitions associated with depression. Respondents indicate how often they felt a particular way during the previous week on a 4-point scale ranging from rarely/never (1) to most of the time (4). Items were averaged to derive measures of depressive symptoms for mothers and fathers with Cronbach's α = .85 and .82 respectively.

Avoidant coping

Parents completed the Ways of Coping-Revised (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985) prenatally by rating the extent to which they use particular strategies to handle stress during difficult situations on a scale from 0 (not used) to 3 (used a great deal). Items from the distancing (6 items; e.g., tried to forget the whole thing) and escape-avoidance (8 items; e.g., wished the situation would go away or somehow be over with) subscales were averaged to create a single measure of avoidant coping (α = .80 for mother and .76 for fathers).

Beliefs about infant crying

Parents completed the Infant Crying Questionnaire, a measure designed by the authors, in which they rated how often they believed certain things about infant crying and wanted to achieve specific outcomes when their infants cried on a 5-point scale ranging from never (1) to always (5). The scale is best described as a measure of global or general beliefs about crying as it did not specify the context in which infant crying occurred. The scale yielded 21 infant-oriented items (e.g., I want to make by baby feel safe/secure, I think my baby is trying to communicate with me, the way I respond helps my baby learn how to cope with emotions; α = .78 for mothers and .82 for fathers) and 18 parent-oriented items (e.g., I want my baby to stop crying quickly because crying bothers me; I let my baby cry it out so he/she doesn’t get spoiled; α = .80 for mothers and .75 for fathers). Importantly, some parents may endorse items about minimizing crying out of concern for their infants’ future development (e.g., doesn’t get spoiled). However, to the extent that they reflect stricter, more negative, and less valuing attitudes about children’s negative emotions, which have been demonstrated to undermine children’s emotional well-being (Gottman, Katz, & Hooven, 1996), classifying them as infant-oriented seems inappropriate. Items were averaged within subscales to yield measures of parents’ infant-oriented and parent-oriented beliefs about crying, which were maintained as separate dimensions consistent with prior research (Coplan, Hastings, Lagacé-Séguin, & Moulton, 2002; Hastings & Grusec, 1998). Parents’ scores on these dimensions correlated with observed maternal sensitivity to infant distress at 6 months and with both mothers’ and fathers’ self-reports of how they respond to toddler distress and predicted infant mother attachment security assessed via the Strange Situation demonstrating predictive validity (Leerkes, Gudmundson, & Burney, 2010).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Missing data was imputed using the NORM (Schafer, 1999) software program which uses an Expectation-Maximization algorithm to generate start values for the replacement of missing data. Because less than 5% of data overall was missing for both mothers and fathers, single imputation was used to replace missing values. Demographic variables, predictor variables including interactions, and dependent variables were all included in the imputation model to preserve associations between the variables. Next, descriptive statistics were calculated for all primary variables and paired t-tests were used to compare mothers’ and fathers’ scores on the same measures. These appear in Table 1. Mothers reported significantly higher infant-oriented beliefs and significantly lower parent-oriented beliefs than did fathers. Third, participant age, education, income, minority status and child sex were examined as potential covariates via correlations and t-tests. No covariates were identified for mothers. Education correlated negatively with fathers’ positive beliefs about crying (r(86) = −.27; p < .05) and correlated negatively with their use of avoidant coping (r(86) = −.24; p < .05). Thus, father education was entered as a covariate in the regression predicting fathers’ infant-oriented beliefs.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Paired t-tests Comparing Mothers and Fathers

| Mothers | Fathers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| Emotion Minimization | 1.82 | .53 | 1.89 | .52 | 0.87 |

| Global Empathy | 3.80 | .46 | 3.66 | .53 | 1.82t |

| Trait Anger | 1.88 | .55 | 1.81 | .53 | 0.81 |

| Depression | 1.51 | .32 | 1.43 | .31 | 1.92t |

| Avoidant Coping | 1.07 | .44 | 1.02 | .42 | 0.84 |

| Infant-Oriented Beliefs | 4.04 | .35 | 3.74 | .40 | 5.27** |

| Parent-Oriented Beliefs | 2.33 | .41 | 2.51 | .39 | 3.33** |

p< .10,

p< .05,

p<.01, df = 86

Direct Effects on Parents’ Beliefs about Crying

As a preliminary test of the direct effects hypotheses, simple correlations were calculated among key variables and are illustrated in Table 2. Consistent with prediction, childhood emotion minimization was negatively associated with mothers’ and fathers’ infant-oriented beliefs about crying, albeit at trend level, and was positively associated with fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs about crying. As predicted, a history of emotion minimization was linked with greater trait anger, depressive symptoms, and avoidant coping among mothers. This was not the case for fathers. Contrary to prediction, trait empathy and anger were unrelated to parents’ beliefs about crying. Depressive symptoms were linked with more parent-oriented beliefs about crying for both mothers (at trend level) and fathers, as predicted. Consistent with prediction, avoidant coping was linked with greater parent-oriented beliefs about crying for mothers. For fathers, avoidant coping operated opposite of prediction as it was linked with more infant-oriented beliefs about crying. Finally, mothers’ and fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs about crying were positively associated as predicted; this was not the case for infant-oriented beliefs.

Table 2.

Simple Correlations Among Primary Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotion Min. | .14 | −.08 | .02 | .11 | .08 | −.18t | .29** |

| 2. Global Empathy | −.16 | −.06 | −.09 | .12 | .10 | .13 | .14 |

| 3. Trait Anger | .25* | −.39** | −.06 | .31** | .28** | .16 | .16 |

| 4. Depression | .32** | −.06 | .28** | .23* | .36** | .03 | .34* |

| 5.Avoidant Coping | .31** | −.08 | .21** | .26* | .18t | .27* | .16 |

| 6.Infant-Or Beliefs | −.19t | .07 | −.05 | −.09 | .13 | −.04 | .16 |

| 7. Parent-Or Beliefs | .11 | −.06 | .12 | .19t | .33** | −.14 | .28** |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Mother correlations appear below the diagonal, N = 87; Father correlations appear above the diagonal, N = 87; Correlations between parallel mother and father variables appear on the diagonal and are boldfaced.

The independence of these direct effects from one another was tested using simultaneous multiple regression. In order to maintain an adequate subject to predictor ratio, variables hypothesized to operate as main effects that were not significantly correlated with the outcomes were dropped from further consideration. Specifically, global empathy, and trait anger were dropped from consideration for mothers and fathers, depressive symptoms were dropped completely for mothers and for fathers in relation to infant-oriented beliefs. Avoidant coping was dropped for mothers’ infant-oriented beliefs and fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs about crying. The proposed moderating effect and main effects used to compose the interaction term were included in these models as well: partners’ infant-oriented beliefs and its product term with emotion minimization. Variables were centered prior to calculating interaction terms. This resulted in regression models with 6 or fewer predictors, meeting the rule of thumb that there be 10 participants per predictor.

The hypothesized direct effects are displayed in the top half of Table 3. None of the proposed direct effects predicted mothers’ infant-oriented beliefs about crying. Consistent with prediction, mothers were more likely to endorse parent-oriented beliefs about crying if they had avoidant coping styles and partners’ who endorsed parent-oriented beliefs about crying. The unanticipated positive association between fathers’ avoidant coping and their infant-oriented beliefs about crying remained significant in the regression model. Finally, consistent with prediction, fathers were more likely to endorse parent-oriented beliefs about crying if they reported a childhood history of emotion minimization and high depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Multiple Regressions Predicting Parents’ Beliefs About Infant Crying

| Mothers |

Fathers |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infant-Oriented Beliefs |

Parent-Oriented Beliefs |

Infant-Oriented Beliefs |

Parent-Oriented Belief |

|||||||||

| B | SE(B) | β | B | SE(B) | β | B | SE(B) | β | B | SE(B) | β | |

| Education | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.06 | .03 | −.21* | -- | -- | -- |

| Hypothesized Direct Effects | ||||||||||||

| Emotion Minimiz. | −.13 | .07 | −.20t | .03 | .08 | .04 | −.17 | .08 | −.22* | .18 | .08 | .22* |

| Depressive Symp. | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | .39 | .13 | .31** |

| Avoidant Coping | -- | -- | -- | .29 | .10 | .31** | .27 | .11 | .28* | -- | -- | -- |

| P Parent-Or Beliefs | -- | -- | -- | .27 | .11 | .26* | -- | -- | -- | .13 | .11 | .12 |

| Moderator | ||||||||||||

| P Infant-Or Beliefs | −.08 | .09 | −.09 | −.05 | .11 | −.05 | −.12 | .12 | −.11 | .14 | .11 | .12 |

| Hypothesized Moderated Effect | ||||||||||||

| Min X P I-Or Beliefs | .59 | .27 | .23* | −.07 | .32 | −.02 | .07 | .24 | .03 | −.44 | .22 | −.22* |

| Model F | 2.75* | 3.49** | 3.43** | 5.16** | ||||||||

| Total R2 | .09 | .18 | .18 | .25 | ||||||||

p< .10,

p < .05,

p < .01

Note: N = 87; P = partner; Or = Oriented, Min = Emotion minimization.

Mediated Effects of Childhood Emotion Minimization on Beliefs about Crying

Contrary to prediction, there was no evidence to support the view that the effect of childhood emotion minimization on parents’ beliefs about crying was mediated by their emotional dispositions. The pattern of simple correlations, displayed in Table 2, demonstrated that none of the emotional disposition variables correlated significantly with both a history of emotion minimization in childhood and parents’ beliefs about infant crying.

Moderated Effects of Childhood Emotion Minimization on Beliefs about Crying

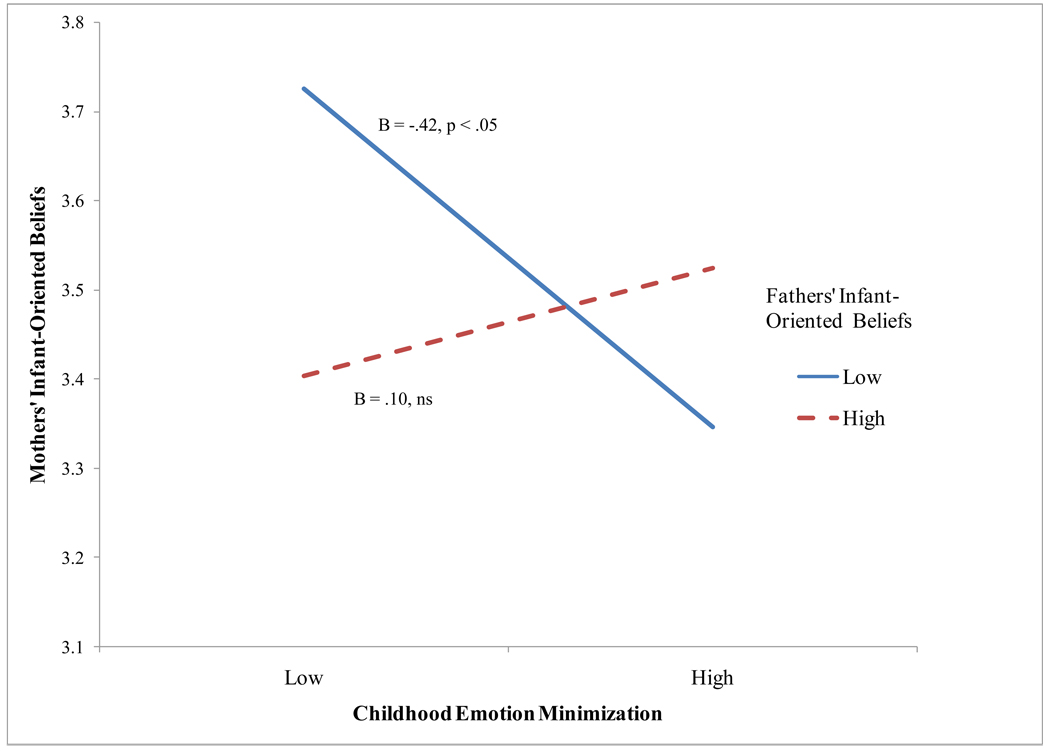

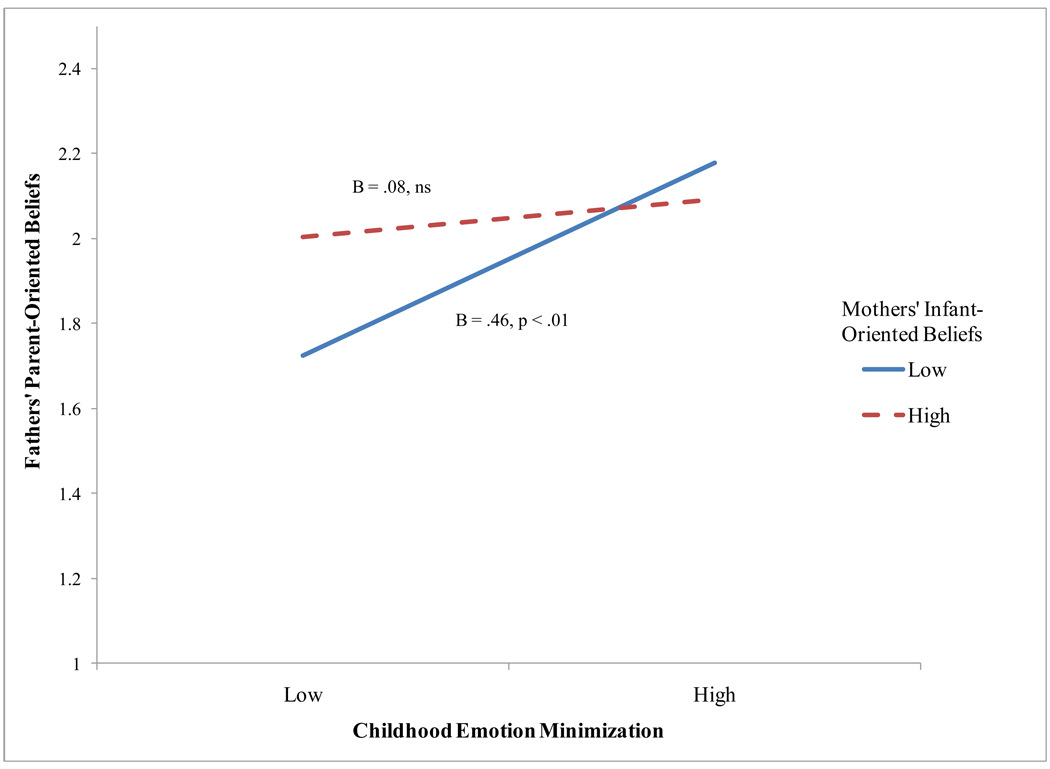

The coefficients testing the proposed moderating effect of the partner’s infant-oriented beliefs about crying on the association between childhood emotion minimization and beliefs about crying are displayed in the bottom half of Table 3. To interpret significant interactions, simple slopes for the association between emotion minimization and parents’ beliefs were calculated at +1 and −1 SD from the mean of the partners’ beliefs (Whisman & McClelland, 2005). Two of the four tested moderating effects were significant, and each supported the buffering hypotheses. Specifically, for mothers, a history of emotion minimization interacted with partners’ infant-oriented beliefs about crying in relation to their infant-oriented beliefs about crying. As illustrated in Figure 1, a history of emotion minimization was negatively associated with mothers’ infant-oriented beliefs only if their partners had low infant-oriented beliefs about crying, B = −.42, p < .05, but not if their partners had high infant-oriented beliefs B = .10, ns. Likewise, the effect of a history of emotion minimization on fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs about crying was moderated by mothers’ infant-oriented beliefs. Consistent with prediction, emotion minimization was positively associated with fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs about crying if their partners endorsement of infant-oriented beliefs was low, B = .46, p < .01, but not if their partners’ endorsement of infant-oriented beliefs was high, B= .08, ns, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of fathers’ infant-oriented beliefs on the association between a history of childhood emotion minimization and infant-oriented beliefs about crying for mothers.

Figure 2.

The moderating effect of mothers’ infant-oriented beliefs on the association between a history of childhood emotion minimization and parent-oriented beliefs about crying for fathers.

Summary of Models

To evaluate the utility of the entire conceptual model, the significance of each regression model was examined and total effect sizes were evaluated based on Cohen’s f2 (1988) such that .02 is considered a small effect, .15 a medium effect, and .35 a large effect. The model predicted significant variation in mothers’ infant-oriented beliefs, but the total effect size was in the small to moderate range (f2 = .10). The model was significant in relation to mothers’ parent-oriented beliefs, and the effect size was moderate (f2 = .22) as was the case for fathers’ infant-oriented beliefs (f2 = .22). The model was significant in relation to fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs about crying and the total effect size was large (f2 = .35). Thus, the proposed model predicted relatively more variation in both mothers and fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs than infant oriented beliefs, and the model was more predictive of fathers’ beliefs about crying than mothers.

Discussion

Given evidence that parental beliefs guide parenting behavior, identifying the origins of those beliefs is important from both a basic and applied perspective. In the present study, emotion socialization in the family of origin and the partners’ beliefs about crying emerged as the most consistent predictors of parents’ beliefs about crying in that each was related to three of the four outcomes as a main effect or in conjunction with one another. These effects are discussed below and similarities and differences between mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about crying and their origins are highlighted.

Parents and Partners as Sources of Knowledge

For fathers, a history of having negative emotions ridiculed, ignored, and punished during childhood predicted fewer infant-oriented beliefs and more parent-oriented beliefs about crying as a direct effect, although the latter was qualified by an interaction with partners’ beliefs as discussed below. Thus, there was some support for the view that parents beliefs about infant crying are influenced by the manner in which their parents responded to their own negative emotions in childhood. Contrary to prediction, there were no mediated effects of emotion minimization on parents’ beliefs about crying via their emotional dispositions.

Mothers’ and fathers’ parent-oriented beliefs were positively correlated, and for mothers this effect remained significant independent of all other predictors. Their infant-oriented beliefs were not correlated. Perhaps the beliefs and related behaviors represented in the parent-oriented items are more overt and salient at this phase of development. That is, in early infancy, parents likely converse about whether or not they should let their infant cry it out to avoid spoiling him or her, and presumably they have to agree with one another in order to enact this strategy, at least when they are both present. In contrast, some infant-oriented beliefs, particularly those that center on future positive development and self-regulation may become more salient and more frequently discussed as the child becomes older and with increased developmental expectations.

The view that the partners’ infant-oriented beliefs about crying would buffer parents from negative effects of a history of emotion minimization in childhood on their beliefs about infant crying was supported for both mothers in fathers, albeit in relation to different types of beliefs. For mothers, emotion minimization in childhood was only linked with less infant-oriented beliefs about crying if their partners did not endorse infant-oriented beliefs about crying. For fathers, a history of emotion minimization was linked with more parent-oriented beliefs about crying only if their partners did not endorse infant-oriented beliefs about crying. This pattern of findings supports the notion that exposure to a partner who is a positive parenting role model and source of parenting knowledge that differs from knowledge derived from the family of origin has the potential to disrupt the continuationof parenting-related phenomenon from the previous generation.

Parents’ Emotional Dispositions

In general, mothers’ and fathers’ emotional dispositions were less consistently related to their beliefs about crying than expected. This was particularly surprising given that affect was one of only two potential origins of parental beliefs identified by Sigel and McGillicuddy-DeLisi’s dynamic belief systems model (2002), and one would expect that affective tendencies would be particularly relevant to beliefs about an emotion relevant child behavior such as crying. Specifically, trait empathy and anger were unrelated to all measures of parents’ beliefs about crying. Perhaps empathy and anger in response to infant crying would be more predictive of parents’ beliefs about crying than global trait empathy and anger. That is, infant crying is a specific social cue that may elicit emotions that are not predicted by ones trait-like emotions. Cue specific affect may be more relevant to the construction of a belief about that cue. Consistent with this view, mothers’ empathy and anger/anxiety in response to crying were correlated with their beliefs about crying (Leerkes, in press).

As predicted, depressive symptoms were linked with more parent-oriented beliefs about crying for fathers, supporting the notion that the pattern of affect and cognition affiliated with depression undermines an orientation toward others’ needs. However, that only one of four possible associations was significant does not lend overwhelming support to this hypothesis. This may be a function of the limited range of depressive symptoms in this low-risk sample. Alternatively, as trajectories in depression vary significantly over the transition to parenthood (Keeton, Perry-Jenkins, & Sayer, 2008), it may be that individual differences in trajectories of emotional dispositions are more predictive of beliefs about crying in the first year of life than a single measure prior to the infant’s birth.

Finally, avoidant coping appeared to be maladaptive for mothers as it was linked with more parent-oriented beliefs as predicted. The tendency to avoid problems and negative emotions likely contributes to mothers’ parent-oriented beliefs about crying in at least two ways. First, such mothers may want to minimize or ignore crying because it is aversive to them consistent with a general avoidant tendency (Leerkes & Crockenberg, 2006), and second, they may be unaware of or devalue more active emotion-focused and infant-oriented responses because they have little personal experience with them. In contrast, for fathers, avoidant coping appeared to be adaptive in that it predicted more infant-oriented beliefs. Perhaps fathers’ tendency to avoid their own problems does not generalize to beliefs about infant crying because they view their children’s emotion socialization as the mothers’ primary responsibility, particularly in infancy, and as somewhat beyond their control as they spend less time in direct contact with their infants. Thus, fathers who prefer to avoid their own problems may still endorse infant-oriented beliefs such as “I want my child to feel better” because they view it as their wives’/partners’ responsibility to make sure this happens. Consistent with this view, avoidant coping strategies are primarily maladaptive in response to stressors that are perceived as controllable (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984); and primiparous fathers perceive parenting as less threatening, challenging, and self-controllable than primiparous mothers (Levy-Shiff, 1999). However, replication is needed before drawing strong conclusions from this unanticipated result.

Differences Between Mothers and Fathers

Overall, our model predicted more variation in fathers’ beliefs about crying than those of mothers. In general, emotional dispositions operated similarly for mothers and fathers in that they predicted relatively little variation in both parents’ beliefs about crying; a quarter or fewer of the predicted emotional disposition effects were apparent for either parent. However, avoidant coping operated differently for mothers than fathers as discussed above. The other partners’ beliefs about crying had an effect on both mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about crying as evidenced by one significant main effect and one significant moderating effect for mothers and one moderating effect for fathers. This was counter to our expectation that fathers’ would be more influenced by mothers’ beliefs because they view mothers as more expert in this area, but consistent with the view that parenting partners influence one another in important ways.

A history of childhood emotion minimization had somewhat more of an effect on fathers’ beliefs than mothers’ as evidenced by two significant main effects (qualified by an interaction with partner beliefs) and one moderated effects for fathers in contrast to only one significant moderated effect for mothers. This is consistent with our view that fathers’ beliefs about crying would be more influenced by their parents’ emotion-related behavior because they have less direct personal experience with young children to draw from in forming their own beliefs (Parke, 2002).

Importantly, Sigel and McGillicuddy-DeLisi (2002) emphasize the role of knowledge in forming beliefs, and it seems likely that mothers have a number of direct sources of knowledge about children that fathers do not. For example, women tend to have had more prior experience caring for siblings and other children, and are more likely to have pursued education and careers relevant to child development (e.g., teaching) or emotions (e.g., counseling, social work) and to spend time interacting with and thus observing other parents’ parenting behavior than do fathers (Padavic & Reskin, 2002; Parke, 2002). Identifying other predictors of mothers’ beliefs about crying is important given they tend to be the primary caregivers during early infancy (Parke, 2002).

We also examined mean differences in mothers’ and fathers’ beliefs about crying and found that mothers endorsed more infant-oriented and fewerparent-oriented beliefs about crying than fathers. This pattern of results is comparable to those of Wong et al. (2008), who found that mothers were more accepting/valuing of child negative emotions, a child-oriented belief, a finding they attributed to women’s greater valuing of emotion expression in general. It may also be that fathers’ are motivated to focus on their own needs if they feel they are competing with their infants for their wives’/partners’ attention (Belsky & Kelly, 1994).

Applied Implications

In sum, the present results lend support to the view that the manner in which negative emotions are treated in the family of origin become a legacy that influences subsequent beliefs about crying, especially for fathers, but the extent to which this is true is dependent on the presence or absence of current buffers. The partners’ infant-oriented beliefs about crying ameliorate the negative effect of a history of emotion minimization on parents’ beliefs about infant crying. Given evidence linking parental beliefs to parenting behavior and child outcomes, this pattern of findings suggests that identifying families at risk for emotional dysfunction is possible during the prenatal or early postpartum period by administering a questionnaire or interview to screen the extent to which their emotions were minimized in childhood. Next, practitioners could determine whether likely buffers are readily available and make efforts to bolster their availability and the parents’ ability to make use of them. The current results, coupled with evidence of the utility of cognitively oriented parenting interventions in promoting positive parenting (see Azar, Reitz, & Goslin, 2008 for a review), suggest that prevention and intervention efforts could focus on helping parents identify their beliefs about crying and their origins. It may be possible to promote cognitive restructuring about crying and how parents should respond to it. Emphasizing alternative parenting beliefs and strategies in response to crying may also be a useful avenue to pursue. As partners’ beliefs were related as either main effects or in conjunction with a history of emotion minimization, it is likely important to include both mothers and fathers in these efforts. Such efforts have the potential to enhance parental sensitivity, particularly to negative emotions, which may in turn contribute to young children’s social-emotional well-being.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

A number of limitations of the current work must be acknowledged. First, the sample was relatively small and low risk, and ethnic diversity was too limited to allow for an examination of racial/ethnic differences in beliefs about crying or their origins. Given sample size, power to detect small effects was limited. In addition, all measures were self-report; thus resulting associations may be inflated due to shared method variance. These limitations are somewhat offset by the strengths which include the inclusion of mothers and fathers, the longitudinal nature of the design, and efforts to begin to address an important gap in the infant-parent literature.

In the future, researchers may investigate the role of other sources of knowledge about children and emotion as well as trajectories in affect over the transition to parenthood in relation to beliefs about crying. Examining the role of child characteristics is also of interest. Parents of infants who are high in negative emotionality (e.g., easily and intensely distressed and difficult to soothe) may develop more parent-oriented than infant-oriented beliefs as a function of caring for their more demanding infants, particularly if other stressors are present (Crockenberg, 1986). These parents may perceive their infants as highly demanding and less responsive to their behavioral responses to crying which may modify their beliefs over time. An additional area for further investigation is the possibility that parents’ beliefs about crying, and their origins, vary across contexts (e.g., nighttime crying, crying during caretaking tasks such as diapering, crying during separations) and by infant age. Such efforts should be undertaken in larger and more diverse samples.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (R03 HD048691) and by a New Faculty Grant and Summer Excellence Award from the Office of Sponsored Programs and seed money from the Human Environmental Sciences Center for Research at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. We are grateful to the childbirth educators who allowed us to enter their classes for recruitment and to the families who generously gave their time to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Azar ST, Reitz EB, Goslin MC. Mothering: Thinking is part of the job description: Application of cognitive views to understanding maladaptive parenting and doing intervention and prevention work. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:295–304. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Kelly J. The transition to parenthood: How a first child changes a marriage. Why some couples grow closer and others apart. New York: Dell; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Besser A, Priel B. Trait vulnerability and coping strategies in the transition to motherhood. Current Psychology. 2003;22:57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Botwin M, Buss D, Shackelford T. Personality and mate preferences: Five factors in mate selection and marital satisfaction. Journal of Personality. 1997;65(1):107–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coplan RJ, Hastings PD, Lagacé-Séguin DG, Moulton CE. Authoritative and authoritarian mothers’ parenting goals, attributions, and emotions across different child rearing contexts. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S. Are temperamental differences in babies associated with predictable differences in caregiving? In: Lerner JV, Lerner RM, editors. New Directions for Child Development: Temperament and Social Interaction During Infancy and Childhood. Vol. 31. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1986. pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg S, McCluskey K. Change in maternal behavior during the baby's first year of life. Child Development. 1986;57:746–753. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. The effects of dispositional empathy on emotional reactions and helping: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality. 1983;51:167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Dix TH. Parenting on behalf of the child: Empathic goals in the regulation of responsive parenting. In: Sigel IE, McGillicudy-DeLisi AV, Goodnow JJ, editors. Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children. Vol. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1992. pp. 319–346. [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Reinhold DP, Zambarano RJ. Mothers’ judgment in moments of anger. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1990;36:465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL. Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry. 1998;9:241–273. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0904_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Miller P. The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:91–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Ways of coping (revised) University of California, Berkeley, Stress and Coping Project, Psychology Department; 1985. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Mount JH, Cordy NI, Whiffen VE. Depression and perceptions of early parenting: A longitudinal investigation. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;152:24–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, Katz LF, Hooven C. Parental meta-emotion philosophy and the emotional life of families: Theoretical models and preliminary analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:243–268. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Thompson JA, Parker AE, Dunsmore JC. Parents' emotion-related beliefs and behaviors in relation to children's coping with the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Infant and Child Development. 2008;17:557–580. [Google Scholar]

- Harkness S, Super CM, Keefer CH. Learning how to be an American parent: How cultural models gain directive force. In: D’Andrade RG, Strauss C, editors. Human motives and cultural models. New York: Cambridge; 1992. pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Grusec JE. Parenting goals as organizers of responses to parent-child disagreement. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:465–479. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Rubin KH. Predicting mothers beliefs about preschool-aged children’s social behavior: Evidence for maternal attitudes moderating child effects. Child Development. 1999;70:722–741. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoglund CL, Nicholas KB. Shame, guilt, and anger in college students exposed to abusive family environments. Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10:141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Zambarano RJ. Passing the rod: Similarities between parents and their young children in orientations toward physical punishment. In: Sigel IE, McGillicudy-DeLisi AV, Goodnow JJ, editors. Parental belief systems: The psychological consequences for children. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 115–142. [Google Scholar]

- Keeton CP, Perry-Jenkins M, Sayer AG. Sense of control predicts depressive and anxious symptoms across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:212–221. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Friesenborg AE, Lange LA, Martel MM. Parents’ personality and infants’ temperament as contributors to their emerging relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2004;86:744–759. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koestner R, Franz C, Weinberger J. The family origins of empathic concern: A 26 year longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:709–717. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.58.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L. Socialization goals and mother-child interaction: Strategies for long-term and short-term compliance. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1061–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Lagacé-Séguin DG, Coplan R. Maternal emotional styles and child social adjustment: Assessment, correlates, outcomes, and goodness of fit in early childhood. Social Development. 2005;14:613–636. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal and Coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM. Predictors of maternal sensitivity to infant distress. Parenting: Science and Practice. doi: 10.1080/15295190903290840. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Blankson AN, O’Brien M. Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and non-distress on social-emotional functioning. Child Development. 2009;80:762–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Crockenberg SC. Antecedents of mothers’ emotional and cognitive responses to infant distress: The role of mother, family, and infant characteristics. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2006;27:405–428. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Crockenberg SC, Burrous CE. Identifying components of maternal sensitivity to infant distress: The role of maternal emotional competencies. Parenting: Science & Practice. 2004;4:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Leerkes EM, Gudmundson JA, Burney RV. The Infant Crying Questionnaire: A new measure of parents' beliefs about crying; Poster presented at the International Conference on Infant Studies; Baltimore, MD: 2010. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Shiff R. Fathers’ cognitive appraisals, coping strategies, and support resources as correlates of adjustment to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:554–567. [Google Scholar]

- Lutenbacher M. Relationships between psychosocial factors and abusive parenting attitudes in low-income single mothers. Nursing Research. 2002;51:158–167. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200205000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Booth-LaForce C. Maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress as predictors of infant-mother attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:247–255. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meesters C, Muris P. Perceived parental rearing behaviours and coping in young adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:513–522. [Google Scholar]

- Padavic I, Reskin B. Women and Men at Work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD. Fathers and families. In: Bornstein M, editor. Handbook of Parenting: Vol 3: Being and becoming a parent. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 27–74. [Google Scholar]

- Parker G. Parental reports of depressives: An investigation of several explanations. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1981;3:131–140. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(81)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A parental bonding instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1979;52:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reizer A, Mikulincer M. Assessing individual differences in working models of caregiving: The construction and validation of the mental representation of caregiving scale. Journal of Individual Differences. 2007;28:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. NORM: Multiple imputation of incomplete multivariate data under a normal model (Version 2.0) 1999 [Computer software] available from: http://www.stat.psu.edu/~jls/misoftwa.html.

- Schuetze P, Zeskind PS. Relations between women’s depressive symptoms and perceptions of infant distress signals varying in pitch. Infancy. 2001;2:483–499. doi: 10.1207/S15327078IN0204_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigel IE, McGillicuddy-DeLisi AV. Parent beliefs are cognitions: The dynamic belief systems model. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting: Vol 3: Being and becoming a parent. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 485–508. [Google Scholar]

- Simons R, Beaman J, Conger R, Chao W. Gender differences in the intergenerational transmission of parenting beliefs. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1992;54:823–836. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner EA, Edge K, Altman J, Sherwood H. Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:216–269. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State–trait anger expression inventory professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Whisman MA, McClelland GT. Designing, testing and interpreting interactions and moderator effects in family research. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:111–120. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MS, Diener ML, Isabella RA. Parents’ emotion related beliefs and behaviors and child grade: Associations with children’s perceptions of peer competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:175–186. [Google Scholar]

- Zeifman DM. Predicting adult responses to infant distress: Adult characteristics associated with perceptions, emotional reactions, and timing of intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24:597–612. [Google Scholar]