Abstract

In many energy transducing systems which couple electron and proton transport, for example, bacterial photosynthetic reaction center, cytochrome bc1-complex (complex III) and E. coli quinol-oxidase (cytochrome bo3 complex), two protein-associated quinone molecules are known to work together. T. Ohnishi and her collaborators reported that two distinct semiquinone species also play important roles in NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). They were called SQNf (fast relaxing semiquinone) and SQNs (slow relaxing semiquinone). It was proposed that QNf serves as a “direct” proton carrier in the semiquinone-gated proton pump (Ohnishi and Salerno, FEBS Letters 579 (2005) 4555), while QNs works as a converter between one-electron and two electron transport processes. This communication presents a revised hypothesis in which QNf plays a role in a “direct” redox-driven proton pump, while QNs triggers an “indirect” conformation-driven proton pump. QNf and Q together serve as (1e−/2e−) converter, for the transfer of reducing equivalent to the Q-pool.

Keywords: quinone-induced conformation-driven proton pump, quinone-gated proton pump, direct proton pump, indirect proton pump

Introduction

A major role of NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (complex I) is to transfer electrons from NADH to the quinone pool (Q-pool). Accompanying the transfer of two electrons, it is believed that approximately four protons are transported across the membrane to create the proton electrochemical potential (ΔμH+). Protein-associated quinone molecules are known to play important roles in energy transducing system. QA and QB in the bacterial photosynthetic reaction center [1-2], Qi and Qo in cytochrome bc1 complex (complex III) [3-4] and QL and QH in E coli quinol oxidase (bo3) are good examples [5].

In complex I, the importance of two protein-associated quinone molecules have been emphasized [6-8]. From the measurement of the electron spin relaxation profiles, T. Ohnishi and her collaborators proposed the existence of distinct two semiquinone species, fast relaxing SQNf and slow relaxing SQNs. The SQNf signal is extremely sensitive to the transmembrane ΔμH+ poise, while that of SQNs is ΔμH+ insensitive. Based on a detailed analysis of the direct spin-spin interaction between reduced cluster N2 and SQNf, their mutual distance was calculated as 12 Å. The projection of the N2-SQNf vector along the membrane normal is only 5 Å [9]. Therefore, we proposed a directly quinone-coupled, SQNf-gated proton-pumping mechanism [10], which differs from the reversed Q-cycle mechanism [11].

Here, we will present a revised proton pump model in which two different mechanisms operate in series. Two protons per electron pair are transported via a quinone-gated “direct” proton pump, and the additional two protons are transported by a quinone-induced conformation-driven “indirect” proton pump. The concept of the “indirect proton transport” has been extensively discussed for complex I [12-16]. This terminology may be somewhat misleading because it gives the impression that the transport takes place independent of the redox energy. Even “indirect” proton pump associated with respiration are still ultimately driven by the exergonic electron transfer reactions between NADH and Q-pool.

A question would be raised: What is the immediate energy source, and how does it communicate to the remote indirect proton pumps?

In this paper, we will present a new hypothesis that the “indirect” pump is triggered by energy related to the site occupancy of QNs. The energy is conducted by means of a conformational change of the protein structure to the antiporter homologs to cause the relocation of the channel structure.

Discussion

Direct proton pump mechanism

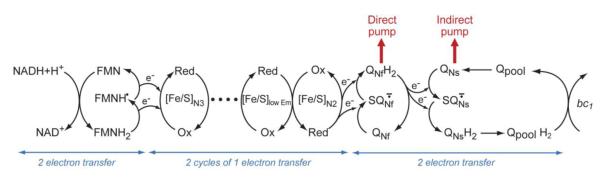

A scheme of the respiratory chain of complex I is shown in Fig. 1. If we approximate the redox reactions in complex I using the standard redox midpoint potential (Em) instead of the actual redox potential (Eh), they cover the range between NADH/NAD+ (Em,pH7= −0.32 eV) and the ubiquinone pool QH2/Q (Em,pH7=+0.09 eV: this was quantitatively measured in photosynthetic reaction center [17]. Thus ΔEm,7 factor for one electron transfer in this redox span is −0.41 eV. The other critical component of the respiratory energy is ΔμH+ across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Its current optimal values for 2 electron transfer is known in the range of 0.16 to 0.19 eV [17]. The available free energy for proton translocation is −ΔG° = ne− ΔEm7 in eV, where ne− is the number of electrons transferred. Then for 2 electron transfer across the mitochondrial or bacterial cytoplasmic membranes, 5.1 ~ 4.3 protons can be transported with 0.82 eV under standard conditions. From this approximation, complex I has enough redox energy to account for the 4H+/2e− stoichiometry.

Fig. 1.

A scheme is to show the flows of electrons and protons in bovine heart complex I. Aarrows of direct pump and indirect pump indicate that these two pumps are driven by two kinds of ubiquinone species. At the end of the cycle, bc1 indicates the coupling to complex III via Qpool.

Ohnishi and Salerno published a hypothesis to explain the high (4H+/2e−) ratio in the coupling of complex I. They used the value of the vertical depth of the electron transport between iron-sulfur cluster N2 and QNf of only , which was obtained from the analysis of the direct spin-spin coupling [9]. From this, they deduced that the QNf is located close to the membrane interface level, and is directly connected to the entrance of the proton well. However, we recognized that explaining the (4H+/2e−) ratio by only one QNf may be difficult.

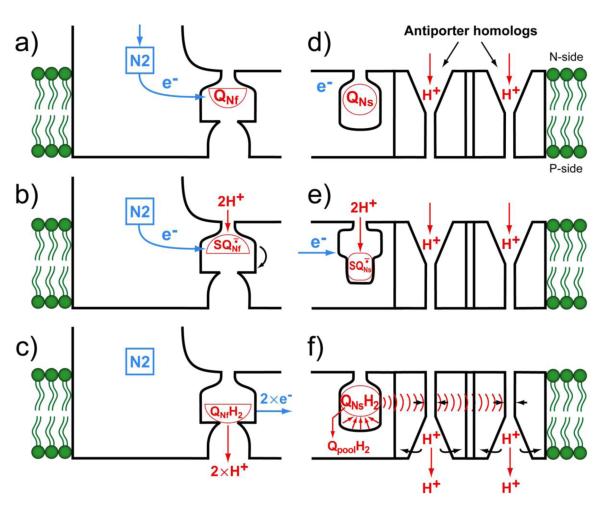

In order to solve the problem, we now propose a revised two semiquinone models. As shown on the left side of Fig. 2, QNf accepts an electron from iron-sulfur cluster N2 (a) to form SQNf which was found to be anionic form below pH 8.5 [9]. Since SQNf intensity is increased by the membrane potential poise and it has a higher affinity constant than both Q and QH2, it binds tightly to the quinone pocket (b). When the semiquinone accepts a second electron from cluster N2, it takes up two protons from the matrix side (N-side). This triggers eversion of the semiquinone-binding protein. When protons bound to the semiquinone are fully reduced to QH2, 2 protons are released into the proton-well. Two electrons are also transferred one by one to QNs (c). This concludes a cycle in which (2H+/2e−) were vectorially transported by the direct pump.

Fig. 2.

Schematic mechanisms of the (a)-(c) QNf-gated “direct” proton pump which transports 2 protons, and (d)-(f) QNs-induced conformation-driven “indirect” proton pump which also transports 2 protons.

Indirect proton pump mechanism

The Klebsiella pneumonia complex I was reported to act as a Na+ pump with a stoichiometry of 2Na+/2e− [18-19]. It was also claimed that E. coli, which is a close relative of K. pneumonia, acts as a Na+ pump [20]. However, Stolpe and Friedrich reported that E. coli complex I is fundamentally a H+ pump, but it is capable of performing a Na+/H+ antiport [21]. In bovine heart complex I, it has become widely accepted that the Na+/H+ antiporter homologs are utilized as the proton channels [21-23].

Although these antiporter homologs are utilized for proton translocation in bovine heart complex I, protons are still pumped across the membrane by the redox energy provided by the electron transport from flavin to quinone, not by an ion gradient as in the antiporters themselves There is no other energy source in complex I. In considering the role of antiporter homologs in the proton pump, several questions may be addressed.

It is interesting that the activity of the antiporter channel is controlled by pH [24]. Effects of pH on the activity of bovine heart complex I was also observed [25]. We do not yet know whether this is related to the mechanism of the antiporters in complex I.

An important point is that the authentic antiporters utilized the electrochemical potential of the Na+ gradient to pump H+, while in complex I, the only available driving force is redox energy. An obvious question is how the energy is transferred to the H+ pump. Investigators in the antiporter field reported that a conformation change causes a reorientation of the channel protein. It also changes the affinity of the key component of the channel to both proton and the monovalent cation [26-28]. Krishnamurthy et al. who studied the Na+-coupled transporters [29], concluded that the antiporters usually employ proton or sodium transmembrane gradients [30-31]. A hypothetical mechanism for the complex I indirect proton pumps that takes all of these points into consideration is shown in the right side of Fig. 2.

QNs is originally in the oxidized form (see (d)). When it accepted an electron, it is reduced to the semiquinone form, which must bind more strongly to the quinone-pocket since it is many order of magnitude more stable than free ubiquinone (Kstability = 2.0 at pH 7.8; [8]) (see (e)). Reduction with a second electron causes the uptake of 2 scalar proton from the N-side, producing the quinol (QNsH2) which has a much weaker binding constant. When the reduced quinone is released from the quinone-pocket, it causes a large conformational change of the pocket as shown in (f). This change will be conducted through the membrane structure to reach the antiporter homologs to cause the relocation of the channel proteins [27]. We assume that the indirect pump releases two protons to the P-side (intermembrane space).

In this figure, QNf-gated direct proton pump (Fig.2(a)-(c)) and QNs-induced indirect conformation-driven proton pump (Fig.2(d)-(f)) are shown as suggested by Sazanov et al. [12]. It is suggested that QNf binding site is located in the NuoH subunit close to the negative side membrane surface [32-36] and QNs -binding site is located on a negative side loop of the NuoN subunit [37].

In summary, QNf and QNs transport 2 protons each, first by the direct mechanism and then, through an indirect mechanism. Then, both QNf and QNs jointly perform the role of converter between one electron transfer and two electron transfer processes.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by an U.S. Public Health Service Grant to TO (R01GM030736).

Abbreviations

- Complex I

NADH-quinone oxidoreductase

- DBQ

decylubiquinone

- SQNf

fast relaxing semiquinone

- SQNs

slow relaxing semiquinone

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Adelroth P, Paddock ML, Sagle LB, Feher G, Okamura MY. Identification of the proton pathway in bacterial reaction centers: both protons associated with reduction of QB to QBH2 share a common entry point. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13086–13091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230439597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Okamura MY, Paddock ML, Graige MS, Feher G. Proton and electron transfer in bacterial reaction centers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1458:148–163. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mitchell P. Protonmotive redox mechanism of the cytochrome b-c1 complex in the respiratory chain: protonmotive ubiquinone cycle. FEBS Lett. 1975;56:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Croft AR. The cytochrome bc1 complex: Function in the context of structure. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:689–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.150251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sato-Watanabe M, Mogi T, Ogura T, Kitagawa T, Miyoshi H, Iwamura H, Anraku Y. Identification of a novel quinone-binding site in the cytochrome bo complex from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:28908–28912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Magnitsky S, Toulokhonova L, Yano T, Sled VD, Hagerhall C, Grivennikofva VG, Burbaev DS, Vinogradov AD, Ohnishi T. EPR characterization of ubisemiquinones and iron-sulfur cluster N2, central components of energy coupling in the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) in situ. J. Bioenergetics and Biomembranes. 2002;34:193–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1016083419979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ohnishi T. Iron sulfur clusters/semiquinones in complex I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1364:186–206. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ohnishi T, Johnson JE, Jr., Yano T, Lobrutto R, Widger WR. Thermodynamic and EPR studies of slowly relaxing ubisemiquinone species in the isolated bovine heart complex I. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Yano T, Dunham WR, Ohnishi T. Characterization of the delta ΔμH+-sensitive ubisemiquinone species (SQNf) and the interaction with cluster N2: new insight into the energy-coupled electron transfer in complex I. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1744–1754. doi: 10.1021/bi048132i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ohnishi T, Salerno JC. Conformation-driven and semiquinone-gated proton-pump mechanism in the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) FEBS Lett. 2005;579:4555–4561. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Dutton PL, Moser CC, Sled VD, Daldal F, Ohnishi T. A reductant-induced oxidation mechanism for complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1364:245–257. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sazanov LA, Peak-Chew SY, Fearnley IM, Walker JE. Resolution of the membrane domain of bovine complex I into subcomplexes: implications for the structural organization of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7229–7235. doi: 10.1021/bi000335t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Friedrich T. Complex I: A chimera of a redox and conformation driven proton pumps? J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2001;33:167–177. doi: 10.1023/a:1010722717257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. The proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase in the respiratory chain: the secret unlocked. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2266–2274. doi: 10.1021/bi027158b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Brandt U. Energy Converting NADH:Quinone Oxidoreductase (Complex I) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:69–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sazanov LA. Respiratory complex I: mechanistic and structural insights provided by the crystal structure of the hydrophilic domain. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2275–2288. doi: 10.1021/bi602508x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dutton PL, Ohnishi T, Daldal F, Moser CC. Coenzyme Q oxidation-reduction reaction in mitochondrial electron transport. In: Kagen VE, Quinn PJ, editors. Coenzyme Q: Molecular Mechanism in Health and Disease. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2001. pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gemperli AC, Dimroth P, Steuber J. The respiratory complex I (NDH I) from Klebsiella pneumoniae, a sodium pump. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33811–33817. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204860200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gemperli AC, Dimroth P, Steuber J. Sodium ion cycling mediates energy coupling between complex I and ATP synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:839–844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237328100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Steuber J. Na translocation by bacterial NADH:quinone oxidoreductases:an extension to the complex-I family of primary redox pumps. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1505:45–56. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00276-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Stolpe S, Friedrich T. The E. coli NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) is a primary proton pump but may be capable of secondary sodium antiport. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:18377–18383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311242200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Seo BB, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. Amiloride inhibition of the proton-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of mammals and bacteria. FEBS Lett. 2003;549:43–46. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00766-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Sakamoto K, Matsuno-Yagi A, Miyoshi H, Yagi T. The ND5 subunit was labeled by a photoaffinity analogue of fenpyroximate in bovine mitochondrial complex I. Biochemistry. 2003;42:746–754. doi: 10.1021/bi0269660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Inoue H, Sakurai T, Ujike S, Tsuchiya T, Murakami H, Kanazawa H. Expression of functional Na+/H+ antiporters of Helicobacter pylori in antiporter-deficient Escherichia coli mutants. FEBS Lett. 1999;443:11–16. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hano N, Nakashima Y, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Terada H, Yoshikawa S. Effect of pH on the steady state kinetics of bovine heart NADH: coenzyme Q oxidoreductase. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2003;35:419–425. doi: 10.1023/a:1027387730474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Karasawa A, Tsuboi Y, Inoue H, Kinoshita R, Nakamura N, Kanazawa H. Detection of oligomerization and conformational changes in the Na+/H+ antiporter from Helicobacter pylori by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:41900–41911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hunte C, Screpanti E, Venturi M, Rimon A, Padan E, Michel H. Structure of a Na+/H+ antiporter and insights into mechanism of action and regulation by pH. Nature. 2005;435:1197–1202. doi: 10.1038/nature03692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Olkhova E, Hunte C, Screpanti E, Padan E, Michel H. Multiconformation continuum electrostatics analysis of the NhaA Na+/H+ antiporter of Escherichia coli with functional implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2629–2634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510914103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Krishnamurthy H, Piscitelli CL, Gouaux E. Unlocking the molecular secrets of sodium-coupled transporters. Nature. 2009;459:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nature08143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Saier MH., Jr. A functional-phylogenetic classification system for transmembrane solute transporters. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:354–411. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.2.354-411.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hediger MA, Romero MF, Peng JB, Rolfs A, Takanaga H, Bruford EA. The ABCs of solute carriers: physiological, pathological and therapeutic implications of human membrane transport proteins. Introduction., Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:465–468. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1192-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Earley FG, Patel SD, Ragan I, Attardi G. Photolabelling of a mitochondrially encoded subunit of NADH dehydrogenase with [3H]dihydrorotenone. FEBS Lett. 1987;219:108–112. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Fisher N, Rich PR. A motif for quinone binding sites in respiratory and photosynthetic systems. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:1153–1162. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schuler F, Casida JE. Functional coupling of PSST and ND1 subunits in NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase established by photoaffinity labeling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1506:79–87. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kervinen M, Patsi J, Finel M, Hassinen IE. A pair of membrane-embedded acidic residues in the NuoK subunit of Escherichia coli NDH-1, a counterpart of the ND4L subunit of the mitochondrial complex I, are required for high ubiquinone reductase activity. Biochemistry. 2004;43:773–781. doi: 10.1021/bi0355903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Murai M, Ishihara A, Nishioka T, Yagi T, Miyoshi H. The ND1 subunit constructs the inhibitor binding domain in bovine heart mitochondrial complex I. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6409–6416. doi: 10.1021/bi7003697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Amarneh B, S.B. V. Mutagenesis of subunit N of the E. coli complex I. Identification of the initiation codon and the sensitivity of mutants to decylubiquinone. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4800–4808. doi: 10.1021/bi0340346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]